Article 4 in the series Data, Design and Civics: Ethnographic Perspectives

On April 1, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced a $317 million federally funded initiative in textile innovation and manufacturing—a national consortium of public and private organizations to be led by MIT. It’s only the most recent project of the Obama administration’s National Network for Manufacturing Innovation, a major effort to re-invigorate the American economy. This ambitious initiative to build manufacturing infrastructure nationwide plans an initial network of 45 Manufacturing Innovation Institutes over 10 years. Led by non-profit organizations, the institutes partner universities, businesses and government agencies with the aim of bridging the gap between basic and applied research in key manufacturing areas such as additive manufacturing (eg, 3D printing), digital manufacturing, lightweight metals, semiconductors, advanced composites, flexible hybrid electronics and integrated photonics.

The unique structure of these public-private partnerships, the technologies and data that are being developed, as well as the source funding (primarily from the departments of defense, energy, and commerce) raise pressing questions for scholars and practitioners alike. How might we develop ethnographic and design research methods that are well suited to grappling with these emerging technologies? How might we document and shape the conversation around the nation’s civic innovation infrastructure? How do we conduct ethnographies of future infrastructures?

Chicago is quickly becoming a locus of emergent digital is manufacturing and design innovation. Of course, the city is a historical epicenter of design and manufacturing. In the late 1930s, for example, Chicago was the home of the New Bauhaus school, the historical root of the Institute of Design and the College of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology. The New Bauhaus was especially concerned with the aesthetics around mass production and the use of technology to improve the quality of human life.

Today Chicago hosts the federally funded UI Labs, comprised of the Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute, City Digital and the Illinois Manufacturing Lab. UI Labs is a cross-institutional network of over 200 partners from industry, government (Department of Defense) and universities, focused on the intersection of computing, big data and the Internet of Things. Its headquarters is a 94,000-foot former window factory warehouse on Goose Island, an artificial island in the North branch of the Chicago River.

On a visit to Goose Island on one of the warmer days last February, the island felt like a liminal space—between Chicago’s industrial past and its promised future as well as between two distinct geographies of the city, the Old Town and Noble Square neighborhoods. The island is home to a mix of high-end car dealerships, corporate R&D facilities, film industry warehouses, a beer company, lighting and equipment companies, printing facilities and back-end tech support for large corporations such as Wrigley and Mars, a ComEd energy plant as well as residential properties. As these geographies of the city are appropriated for the “smart city” agenda, they are also rebranded as Goose Island 2.0, the “innovation island.”

Yet, the island is also the site of emerging economic models that represent alternative civic values and modes of engagement. For example, over the last eight years, a worker-owned cooperative called New Era Windows has formed following a series of strikes after layoffs at Republic Windows and Doors Factory.

City Digital, the lab that focuses on smart cities, is charged with addressing “physical-digital convergence” through “data-driven urban innovation within the built environment” in areas such as energy, infrastructure, transportation, water and sanitation. For example, City Digital plans to conduct pilot projects to demonstrate the value of technology for improving urban infrastructure using the city of Chicago as a test-bed. This approach, which is advocated in the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology report on “Technology and the Future of Cities,” has been challenged by researchers at Georgia Tech, who express concern over the potential for continued uneven development and socio-spatial fragmentation as well as criticize the report’s “technoscientific orientation” and failure to include perspectives of experts in the social sciences and/or urban science disciplines.

In fact, future infrastructures are the subject of significant work across diverse fields. For example, in Program Earth, Jennifer Gabrys presents

“environmental sensing as a technological practice that spans environmental studies, digital culture and computation, the arts, and science and technology studies… Environmental sensing technologies open up new ways of approaching digital technology as material, processual and more-than-human arrangements of experience and participation.”1

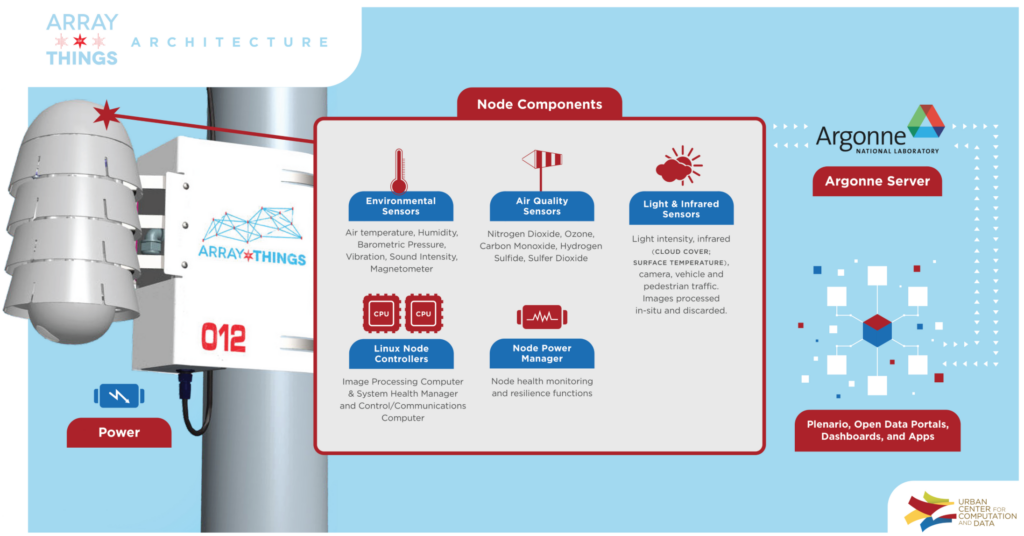

The “urban sensing” project Array of Things is “a network of interactive, modular sensor boxes that will be installed around Chicago to collect real-time data on the city’s environment, infrastructure, and activity.” Described as a “fitness tracker” for the city, the project is led by Argonne National Laboratory, the University of Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and funded by a $3.1 million dollar grant from the National Science Foundation. Unlike City Digital, which aims to commercialize technologies that they are testing, the Array of Things data will be open and free to researchers and the public.

How do ethnographers and design researchers engage in critical and generative modes of studying these projects as they are coming into existence and shaping future infrastructures? In many ways, these projects are determining what will be possible in the future—as well as what will be impossible and who will be excluded from those futures. Intervening in these infrastructures will certainly require the creation and application of different theoretical lenses and methodologies.

Ethnographers and social scientists—in the tradition of scientific laboratory studies or research and development (R&D) studies such as those conducted by Lucy Suchman and Julian Orr—will likely investigate the ways in which emerging technologies are socially shaped and constructed at the same time as these fledgling organizational structures are being created. Design researchers will likely investigate the capabilities of emerging technologies and find ways to map, visualize and imagine their possibilities in order to leverage them by facilitating knowledge exchange across networks of stakeholders.

Following the posthuman turn in critical theory,2 we can do more than merely view data and infrastructures that represent, are shaped by or shape human behavior. These approaches might be understood instead as ethnographic encounters with non-human research participants or a decentering of the human in design.3 We might turn conversations about the transmission, capture and analysis of Big Data toward careful attention to the everyday rituals, habits and practices of small, thick data.

Sarah Pink and colleagues suggest using the lens of digital materiality as an important theoretical filter for the emerging field of design anthropology.4 For example, in a study of the use of Wi-Fi networks, I used spectrum analysis as a tool of digital ethnography to make visible the patterns and behaviors of users that were not possible to see with the naked eye.5 Since that time, a wide variety of approaches to digital anthropology and digital methods have been introduced,6 such as network ethnography7 and trace ethnography.8

Developing suitable approaches for studying the non-human will require a degree of technology engagement and literacy about data, networks and infrastructures that few ethnographers and design researchers possess. However, these literacies, knowledges and resources do exist within citizen science projects, open data meetups, civic technology groups and hackerspaces, which suggests that ethnographic and design research must be collaborative and participatory in order to leverage existing knowledge and invite new stakeholders into the conversation. In short, we must use ethnography and design research to turn citizens into sensemakers, equipped to both imagine and problematize the role of future infrastructures.

Examining sensing projects, Gabrys asks,

“How does it give rise to speculative adventures, or otherwise prevent experimentations with worlds?…Sensorized environments and citizen-sensing practices put in motion specific ways of feeling worlds and of making particular problems matter. In this sense, citizen-sensing practices materialize not as easy fixes to making environmental engagement more democratic but rather as particular expressions of environmental problems, politics, and citizenship.”9

The infrastructures I’ve mapped out here offer only a hint of possible new terrains for ethnographic and design research aimed at understanding and intervening in these systems for the public good. Rather than seeking solutions to problems, we must develop an anticipatory and speculative ethnography that is equipped to grapple with the analytical and methodological challenges of emerging technologies as they interact with socio-economic systems. If data, devices and infrastructures themselves are reconceived as “the user” or the research participant, we can use their stories to advocate for alternative possible futures. These futures can serve to bolster a different set of commitments, values and ethics than those offered by the existing discourse around innovation, smart cities, 3d printing and the internet of things as well as visions about emerging technologies such as driverless cars.

Notes

1. Jennifer Gabrys, Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

2. Braidotti, Rosi, The Posthuman. Boston: Polity, 2013.

3. Laura Forlano, Decentering the Human in the Design of Collaborative Cities, Design Issues, 32:3 (2016).

4. Sarah Pink, Elisenda Ardevol & Debora Lanzeni (eds.), Digital Materialities: Design and Anthropology. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

5. Laura Forlano, Anytime? Anywhere?: Reframing Debates Around Community and Municipal Wireless Networking, Journal of Community Informatics 4:1 (2008); Laura Forlano, Making Waves: Urban Technology and the Coproduction of Place, First Monday, 18:11 (2013).

6. Tom Boellstorff et al., Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton University Press, 2012; Heather A Horst & Daniel Miller, Digital anthropology. A&C Black, 2013; Richard Rogers, Richard, Digital Methods. MIT Press, 2013.

7. P. Howard, Network ethnography and the hypermedia organization: new media, new organizations, new methods. New Media & Society, 4:4 (2002), 550.

8. R Stuart Geiger & David Ribes. (2011). Trace Ethnography: Following Coordination through Documentary Practices. Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS).

9. Gabrys 2016:274.s 2011). She received her PhD in communications from Columbia University.

Related

Introduction to Data, Design & Civics: Ethnographic Perspectives by Carl DiSalvo

Innovation Teams, Mundane Innovation, and the Public Good, Andrew Richard Schrock

Ethnography of Civic Participation: The Difficulty of Showing Up Even when You Are There, Thomas Lodato

Human-Centered Research in Policymaking, Chelsea Mauldin & Natalia Radywyl

“Hey, the water cooler sent you a joke!”: ‘Smart’, Pervasive and Persuasive Ethnography, Nimmi Rangaswamy et al.

Reinvention and Revisioning in an Appalachian Industry Cluster, Christine Miller & Stokes Jones (free article, please sign in)

Knee Deep in the Weeds—Getting Your Hands Dirty in a Technology Organization, Tiffany Romain & Mike Griffing (free article, please sign in)

0 Comments