This contribution is a case study of Spotify, a popular music streaming app, which uses automated recommendations to provide a better user experience to its listeners. Automated recommender systems have mostly been built around understanding user needs and user goals. Our case study presents a meaning-oriented approach aimed at understanding what users regard as meaningful and how an automated recommender system can forge meaning and offer experiences that help develop existing connections to music and generate new ones.

Following the meaning-oriented approach inspired by Lucien Karpik (2010), we were able to better understand how different audience segments engage with music and experience music as meaningful. We identified 2 cultural engagement models that listeners use to relate to music: (1) musical engagement during which music is the focus of the experience; and (2) non-musical engagement, during which the listener is the focus of the experience. Each engagement model uses different types of cognitive and evaluative aids, which we refer to as cues and proof points, to derive meaning from listening experiences. We also identified nine distinct types of experiences of meaning defined by distinct types of cues and proof points.

The proposed approach is applicable to the study and innovation of experience-led digital platforms and recommender systems.

Keywords: meaning, recommender systems, music, streaming

Scale is a particularly urgent theme when researching and designing for digital platforms, algorithmic technologies and the attention economy. Some streaming platforms, such as Spotify, Netflix and YouTube, are based on business models which require them to acquire millions of users and provide value by creating customized, engaging experiences. In order to do that, these interfaces need to be automated so they can harness data to offer personalized content relevant to users’ tastes, contexts and moods.

In order to provide delightful listening experiences in every session for every listener, Spotify faces specific challenges and opportunities related to the affordances of its main medium, sound. Spotify is one of the unique applications where most of the user experience happens through people’s ears, brains and bodies, as opposed to their eyes. This poses several challenges when trying to understand what the value of user experience is and how to improve it.

First, unlike visual interfaces, where in-app interactions like time on the screen, likes and saves are the behaviors that could be used as proxies for understanding the value that users are deriving from the product, a lot of listening sessions on Spotify are hands and eyes free. This means that once users hit ‘Play’ and listen, we know very little about what experience they’re having. On top of that, any behaviours with the visual interface are highly driven by the context that listeners are in. For example, activities like running and driving a car, by their very nature, prevent people from interacting with the visual interface.

Second, based on the attitudinal segments, different types of users have different expertise in music and different abilities to navigate music, find music they like and discover new music. Their metaphors, expectations and benchmarks for deriving value from listening to music differ significantly and therefore, they require different forms and levels of support and feedback.

Thirdly, music listening itself is contextual. A playlist that is relevant at work might have a totally different meaning when listened to with kids at home and the measure of value evolves continuously with context.

Finally, while Spotify had a good understanding of what users’ needs are in various contexts, scenarios and use cases, there was a gap in understanding what they experience as meaningful. Our challenge was to understand how and why users derive meaning from music and how we might train the recommendation algorithms to respect that nuance of human experience.

Therefore, the underlying research challenge was: how do we scale automated recommender systems to forge meaning and offer content that helps develop existing connections to music and generate new ones?

FRAMING THE PROBLEM

In thinking beyond user needs and Jobs To Be Done (see, for example, Ulwick 2016), we were inspired by the sociologist Lucien Karpik and his book Valuing the Unique: The economics of singularities (2010). In this work, Karpik argues that cultural products such as music, wine, novels and movies, are singularities – complex, multidimensional goods, the value of which can’t be reduced to their specific features. It would be silly to claim one song has more value because it is longer, or because the singer hits higher notes. Or that a glass of red wine should be more expensive because it is a darker hue. Focusing on features in isolation misses the point.

Because value cannot be easily assigned to singularities, markets of singularities rely on complex mechanisms that enable actors to make decisions and choices and navigate uncertainty. Whereas in markets of commensurable goods, actors compare costs and benefits, in markets of singularities, they rely on what Karpik calls judgement devices and trust devices. Judgement devices “act as guideposts for individual and collective action” (Karpik 2010, 44) by providing cognitive support and opinion. Examples include reviews, charts or personal recommendations (Karpik 2010, 44–54). Trust devices help remove, dissipate or suspend uncertainty (Karpik 2010, p. 56) because they are often part of larger symbolic systems, such as social norms or formal authority. In the case of singularities such as movies or wine, we rely on the movie critic or wine connoisseur (and their training, education or expertise) to tell us what to expect, guide us in refining our tastes, teach us how to articulate the nuanced differences in our experience and ultimately, they help us make judgements about what is good and what isn’t, what we like and what we don’t. Because of the cultural complexity of singularities, we rely on these devices to serve as proxies of value.

Music is a type of singularity. It’s a type of product that requires knowledge and tastes for us to be able to make a judgement and choice about what music to listen to. Historically, radio has played an important role for the segment of listeners who are not confident in their ability to make choices about music by offering listening experiences curated by radio hosts who navigated the uncertain cultural field for audiences while also providing non-musical engagement, entertainment and information.

To continue differentiating itself as the leading audio streaming platform, Spotify needed to find ways to become a better ‘judgement device’ and a ‘trust device’ for songs, to use Karpik’s terminology, and to be able to do this in an automated way. However, to do this, we needed to move away from thinking about user needs and to understand what a meaningful experience of music can be.

Needs Versus Meaning

The true meaning of singularities only emerges to the user when they experience them themselves. Unlike user needs or goals, the value of singularities can’t be fully anticipated in advance. For example, Spotify’s previous research using the Jobs To Be Done framework, had identified that most listeners listen to music for fulfilling one or more Jobs (e.g. helping them focus, helping them change their mood, helping them create an ambience etc.). However, the Jobs To Be Done framework does not help in understanding how the value emerges for the listener as the listening experience progresses. For example, two users may derive entirely different meaning from the same good. One person could connect to a song because it soundtracked a breakup while someone else could love the same song because it gets people dancing. Jobs To Be Done framework and need-oriented approaches in general, miss this very important nuance.

Karpik explains that this uncertainty about what is valuable, which is a result of the incommensurability of cultural goods, is the defining characteristic of the market of singularities and requires an entirely different approach to value. In markets of commensurable goods, a consumer, Homo economicus, can make choices based on their needs and the expected costs and benefits. Their satisfaction is then derived in terms of efficiency. In markets of singularities, “Homo singularis must juggle the discovery, interpretation and evaluation of judgement devices; the discovery, interpretation and evaluation of singularities; sometimes the discovery, interpretation and evaluation of his own tastes; and a reasonable use of scarce resources.” (Karpik 2010, 67)

Following Karpik’s distinction between a need-oriented approach and a meaning-oriented approach has enabled us to come up with an entirely different model for thinking about the role that Spotify needs to play for its users and how this should be scaled throughout the organisation. We suggest that a meaning-oriented approach is more suitable for application to any services that offer cultural goods, such as music, video, film, fashion and luxury products, because it opens up opportunities to provide not only personalized experiences but also more relevant and meaningful experiences.

To illustrate the difference between the two approaches, consider a listener who may want to listen to the song Run the World by Beyoncé to improve their mood and feel motivated. Following a need-oriented approach, the job to be done is to enable them to search for the song, find it and play it as quickly as possible and without unnecessary friction to avoid frustration. Following a meaning-oriented approach might reveal that the listener experiences the song as meaningful because they identify with the archetype of a strong woman that this song represents. The recommender system could then songs by other artists who represent the same archetype, such as P!nk.

This distinction between a need-oriented approach and a meaning-oriented approach has implications for research design and analysis. While a need-oriented approach benefits from focussing on jobs to be done, the meaning-oriented approach benefits from the exploration of various judgement and trust devices that people use in order to navigate singularities. These can include recommendations from friends, popularity of artists but also personal aspirations. memories, travel experiences or social norms. A quote from Ken, 32, illustrates the complexity of music experience. Ken cannot easily identify his need or a goal. The meaning of the experience unfolds as his music is enjoyed by others, he gets complimented on it and helps him make new friends.

‘Honestly it’s whatever sounds good to me, that I can imagine myself at the beach listening to it I put it on, or anything that sounds good that I think other people will like… It creates a nice vibe, in the beginning I like it because it hypes you up to volleyball. A lot of people have said my playlist has been good, or they like my playlist and this is one woman in the group keeps on saying, I love your music because she use to be a DJ and then she is like oh! Can you share your playlist… I try to incorporate music that everybody likes so I have everything in there, and it’s constantly updated… It’s good for making friends, makes everyone happy.’

The proposed meaning-oriented approach suggests how we might help users like Ken make choices so they can have a more meaningful experience on Spotify.

Table 1. Comparison of needs-oriented analysis and meaning-oriented approach

| Needs | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Pre-existent – they drive choice | Emergent – can’t be anticipated in advance |

| Binary – are either met or not | Multiple – experienced in multiple, unpredictable forms |

| Choice is rational and based on calculation of expected costs and benefits | Choice and actions are justified when meaning is present |

| Meeting needs does not affect identity | Meaningful experiences affect individual’s identity |

| Systems are judged on efficiency | Systems are judged on the quality and relevance of the meaning |

The table is inspired by Karpik

METHODOLOGY

To tackle this challenge, we conducted ethnographic research with 12 participants in Boston in 2019, representing 2 types of audience segments:

- Lean in users are knowledgeable about music, understand their own tastes, have the vocabulary to articulate their preferences and are confident in discovering new music. These users understand musical genres and remember artists and songs. An example of how a lean in user can express his musical preferences:Listening for the beat, I’m listening for the lyrics, what the artist is actually saying – do they flow on the beat, does it sound good together. Yeah, pretty much a good beat and then like good lyrics can win me over if executed well. (Noah, 25)

- Lean back users are not confident in understanding established categories, such as genres, nor are they confident in their own tastes. They struggle to remember or articulate what they like and rely on others to help them discover new music. An example of how a lean back user expressed her attitude towards music:I’m more a radio person. So when it comes on the radio I’ll listen to it but I would say music is not something I’m like super obsessed … Like I enjoy music, I like it. But some people are always listening to music and always want to search for their own music, create their own playlist like they have a particular taste whereas I’m very much like fine with usually what’s on the radio. (Jennifer, 30)

Recognizing the importance of lean back listeners for further growth, we over-indexed on this segment.

Prior to 3-hour face-to-face in-home interviews, we engaged respondents through mobile diaries, asking them to report on at least 3 instances when a piece of music stood out to them and they experienced it as meaningful. We asked them to capture these settings and describe how they felt and why. In interviews we further probed into these and other instances to understand how people connected to music and how they experienced it as meaningful.

Key to the project’s success and organizational impact was the engagement of stakeholders and various teams and working closely with other researchers. We conducted stakeholder interviews and invited members of the Spotify team to join the fieldwork and asked them to share brief reflections on each interview immediately afterwards. These videos were then shared throughout the organization to engage more people.

During fieldwork, at the end of each day, the team gathered together for a debrief. We put up posters with photos of participants and their homes and captured their most important musical connections. At the end of the download session, we recorded brief videos about each participant and their meaningful musical experiences that were shared via Slack with the wider team.

This process provided ongoing interest in the project in all its phases – from fieldwork and insights to organizational and product implications and further opportunities for engagement between Spotify and Stripe Partners.

INSIGHTS

Altogether, we gathered more than 400 instances of significant connections to music and analyzed them using Airtable to generate insights.

Two Cultural Engagement Models

We identified 2 cultural engagement models that listeners use to relate to music and experience it as meaningful: (1) musical engagement during which music is the focus of the experience; and (2) non-musical, during which the listener is the focus of the experience.

Musical engagement tends to utilize established cognitive tools such as universal vocabulary describing musical properties, classification into genres and historical periods. It draws upon expert opinion and values uniqueness and originality.

Like Kanye West has the song Runaway that came in 2010 and all he does at the beginning of it is, he hits the E6 key, hits it again, hits it again and that goes on for like 15 seconds, he then goes down to E5. Like that one drop in octave, that was so cool for me when I learnt how to do that. (Rodrigo, 25)

Non-musical engagement uses more ‘fuzzy’ classifications often derived from personal experience, rather than universal categories, and tends to be attuned to popularity and common opinion and enjoys relatability of the artist or the song and the sense of being similar to the listener.

At work, I like to listen to Beyoncé. That’s another R&B. Her songs are – they’re appropriate. I like listening to them. … I like Beyoncé because you relate. One of my favorite songs from her is Run the World, how women run the world. (Yasmin, 32)

These two cultural engagement models are products of culture and shape the way we experience and enjoy music and express our passions for music. Both models are available to us and, as the research revealed, people sometimes switch between these models or enjoy music through a combination of both models. For example, we met participants who considered themselves experts in music capable of articulating their tastes in niche genres but there were songs they mostly enjoyed because they reminded them of someone else.

The two cultural engagement models provided more nuance to our understanding of the two audience segments and their ways of listening. We understood that it is not our goal to teach the less knowledgeable users about music in order to nudge them into the musical type of engagement. The lean back listeners were well aware that the musical engagement model was available to them and often had someone in their life who was a lean in listener, however, they did not necessarily want to enjoy music in the same way. For example, Maria, 28, grew up in a strict religious environment and was only allowed to listen to Christian music. Now, she doesn’t want to feel any obligation to listen to music in any specific way.

‘So I grew up in a very strict religious background and there we were not allowed to listen to secular music and could only be religious music and at that time they were like made you focus on the lyrics… I feel like they made you analyze everything single thing and I think that’s why now I don’t wanna analyze. Like I just want to listen and enjoy.’ (Maria, 28)

Lean back listeners like Maria were capable of enjoying music just as much as lean in listeners, however, they often experienced difficulties and lack of confidence in their abilities to find the music they liked and discover new music, which is why they regarded radio as useful. This insight revealed the importance of understanding how Spotify might be a better ‘judgement’ and ‘trust’ device for those listeners who default to the non-musical model of engagement.

Experiences Of Meaning

Inspired by Karpik, in our analysis of the instances of meaningful connections to music, we looked to understand what helped people make decisions and judgements about music and ultimately, how they derived value from listening. No matter what audience segment people belong to or what type of engagement with music they have, they all look for meaning and meaningful listening experiences. However, listeners, especially lean back users, don’t necessarily know where and how to look for it. When they rely on automated recommender systems, they fear ending up in their own echo chambers or with irrelevant suggestions. While we cannot anticipate what they will experience as meaningful, we can give them cognitive and evaluative aids to enable them make choices and validate their efforts.

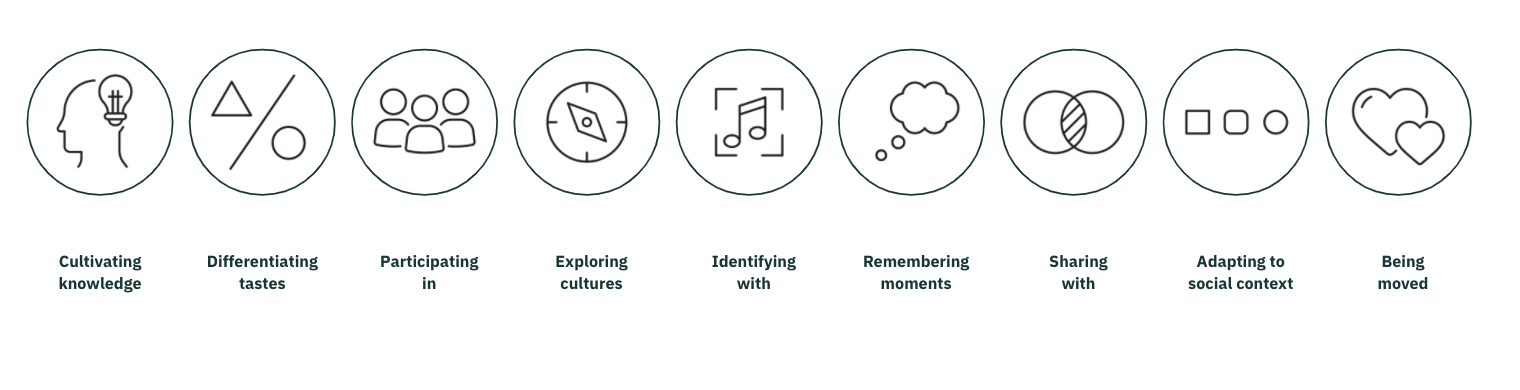

This approach revealed 9 distinct types of experiences of meaning that people have with music, each defined by specific types of tools and aids that we call cues and proof points. Cues provide a sort of navigation towards an experience of meaning and help locate meaning. Proof points help affirm the meaning, validate it and enhance it. An example of a useful cue for Yasmin, who identifies with Beyoncé might be knowing that her song Spirit celebrates Africa. A proof point then would be a video featuring African fashion.

The Nine Experiences of Meaning

The following are the 9 experiences of meaning. We illustrate the differences between the two cultural engagement models and the cues and proof points that help them navigate their experiences.

- Cultivating Knowledge. Music is experienced by building a pool of knowledge and reflecting an existing pool of knowledge, including knowledge about how music is created, how it can be listened to, and how it varies across geographical areas and historical periods. Musical engagement derives meaning from enjoying and developing musical expertise. Listeners locate meaning through established categories, e.g. genres, expert opinion or their own musical training. Meaning is affirmed through proof of authenticity and uniqueness of music. [On the decision to learn to play the piano] It’s totally personal because I am not gonna do anything with the piano side of it, but it’s kind of cool just to learn it. Again, for me being someone who loves music, I just like to play the song as I like to listen to. (Rodrigo, 25)Non-musical engagement derives meaning from connecting music to another area of life or type of art, such as recognizing the aesthetic style of an album artwork. Listeners use general categories (e.g. the 2000s) and friend recommendations to navigate music and enjoy knowing a particular song represents something bigger or is popular.

- Differentiating Tastes. Music is experienced by perceiving the scarcity and heterogeneity of music. Musical engagement derives meaning from feeling that one’s taste is unique and desirable. They use expert validation as a cue and being asked for recommendations is a meaningful proof point. Yeah, if there’s anybody who could talk music just as much as me it’s him. And so like how people go to me I’ll go to him for artists that aren’t well-known and stuff like that. So, it’s always Greg Put You On and it’s always these smaller artists that aren’t as well-known. (Noah, 25)Non-Musical engagement derives value from music when their taste is acceptable and shared with others. They use common opinion to make decisions about music and get more value out of the experience if they realize that their tastes are shared by others.

- Participating In. Music is experienced as a unique encounter with the musician(s) and an embodied experience of music, shared with others. Musical engagement derives meaning from being able to better understand music and one’s tastes through the embodied experience. Scarcity and rarity of performances is an important cue. Non-musical engagement finds meaning in the feeling of intimacy and proximity to the artist. Listeners enjoy the sense of the experience being shared with others.My husband introduced me to [a Haitian band] when we were dating and then I met the lead singer in person and I met the whole group when they were together. So, it’s like I get different emotions because I met them. (Yasmin, 32)

- Exploring Cultures. Music is experienced as a novelty and a comprehensive representation of the particular scene (e.g. popular music, specific genre, specific “terroir” etc.). Musical engagement derives meaning from developing musical expertise in a new culture (or sub-culture). Listeners orient themselves through established categories but through a different context. They enjoy the novelty and discovering something unknown or hidden. Non-musical engagement derives meaning from being able to identify music with travel experiences and other personal interests. Important cues include their past travels and recognizable cultural signifiers (food, dance, etc.). Value of music is reinforced when this can be relevant to others, such as family or friends.I’m the only one who really knows how to dance Copa music. I encourage my little sisters they know, my little brother not at all. He knows nothing about the culture. … And then with having the kid, I’m like now I really like to learn to speak creole, learn to love Haitian food and try to know how to at least dance the little Copa two step, you know that way you’re not completely lost if you were to go to Haiti, you know people will be like, “Oh, he’s a Haitian kid” (Tamila, 29)

- Identifying With. Music is experienced as a language, expression, mental shortcut and visualisations that anchor and elucidate personal narratives and aspirations. Musical engagement derives meaning from sensing that music aligns to both tastes and personal aspirations. Listeners love artists who are central to a wider culture or a sub-genre and value unique stories. Non-musical engagement derives meaning from being able to aspire to the lifestyle the music or artist represents. They recognize desired archetypes and enjoy being able to identify with the wider lifestyle of the artist, including their fashion and values.When I was listening to [the new Beyoncé song], I also looked for the video, and it made that connection of the relationship that she has with her oldest daughter. So, it brought me to the like, oh, I kind of want to have that relationship with my kids… (Yasmin, 32)

- Remembering Moments. Music is experienced as a bridge to anchor memories, provide shared reference points, stories and exclusive tacit language. Musical engagement gives memories a musical significance. For example, listeners enjoy when their lives correspond to important milestones in the history of music or in the careers of their favourite artists. Non-musical engagement likes using music as a shortcut to one’s own personal memories. Listeners locate the meaning of music in their own memories of places, times and people and love sharing memories with others.It helps me remember the people that were in my life, so, Summer camp people were awesome. So, it transports me back to the feeling of safety and being part of something bigger than yourself… (Lilly, 33)

- Sharing With. Music is experienced as part of a shared experience and serves as a shared reference point. Musical engagement enjoys deepening their musical experience with people with similar tastes. They use shared vocabulary and enjoy a proof of shared niche tastes. Non-musical engagement derives meaning from music enabling them to deepen relationships through shared musical references. They use shared activities, such as cooking, or family trips as important cues and love to see a proof of others’ tastes and moods.Going to the concert was like nice because it was a bonding experience and we were there for kind of a longer amount of time, because I bought this Airbnb. And then we were just sort of together and it was like a special shared experience, and then just like music is tied into that.’ (Sylvia, 18)

- Adapting to Social Context. Music is experienced by creating a vibe while minimizing social friction. Musical engagement derives meaning from the alignment between one’s musical tastes and the social context. Listeners enjoy seeing a proof that other people have the same tastes and express enjoyment in a shared way. Non-musical engagement focuses on music being appropriate for the occasion. They locate meaning in social norms and enjoy seeing positive social responses.‘Sometimes we’ll listen to music like if we’re like entertaining or outside or the kids want to play in the yard or something like that, we’re able to drink a beer. We’ll listen like out on an outside speaker… Things like ’80s music, Billy Joel, like you can listen to that around anyone, kids, neighbors without worry about you know offending them… I think outside is more like Jack Johnson and not Drake radio because the neighbors can actually like hear the music so I put a genre here that’s more appropriate.’ (Max, 33)

- Being Moved. Music is experienced by changing the physical or emotional state. Musical engagement derives meaning form the alignment between one’s musical taste and the activity their doing or the state of the mind they’re in. They can explain why they feel moved using musical terms, e.g. specific tempo that gets them motivated, and they can select specific music they know will work for them. Music is integral to working out in the gym. I couldn’t workout without music. It’s motivating. It’s the equivalent of having like a couple of cups of coffee. I work harder when I’m listening to music, it’s motivational in a way… I like loud hip-hop music, a quick beat, aggressive lyrics… Yeah. It’s motivating and it pushes me more than I would push myself if I wasn’t listening to music…It’s motivating and if I didn’t have it, I’m not in charge of the gym.’ (Trevor, 34)Non-musical engagement derives meaning from music that is supportive of an activity and navigates music based on the type of activity or mood, e.g. searching for ‘a running playlist’

DESIGN / PRODUCT IMPLICATIONS

This framework provided a new language and a new foundation for the wider team to think beyond user needs. It also helped understand the role and importance of various types of tools and media that have been an important part of music industry but have not necessarily been successfully embraced by streaming services. For example, the framework explains why listeners who default to the non-musical type of engagement often prefer the radio or why they like YouTube. These services provide them with the cues and proof points they are looking for, such as popularity charts, imagery and comments from other listeners. The insights have enabled Spotify to critically reflect on the fact that the app was more suitable to listeners who default to the musical type of engagement and have given a useful direction for improvement.

The learnings and the framework had direct implications for product and design. The most straightforward application of the framework was for the user interface to use cues and proof points to locate and amplify meaning for the audiences who default to the non-musical type of engagement. For example, possible product interventions in the future could include personalized cover images and annotations.

For example, Yasmin, 32, who liked to listen to artists she could identify with, (e.g. with Beyoncé as a mother, or with P!nk as a strong woman who’s ‘her own boss’) might enjoy being introduced to Lizzo. Useful cues can include visuals celebrating Lizzo’s body positivity and a proof point might be a playlist that offers a gateway to discovering more artists who celebrate body positivity.

The research also helped identify new ways for recommender systems to forge meaning. Meaning is not fixed, it fluctuates depending on context and also changes with time. While meaning cannot be anticipated, we can still aim to optimize it by utilizing cues and proof points. Cues and proof points can help intensify existing connections and add more meaning to them by helping listeners connect to multiple experiences of meaning. For example, Yasmin might enjoy listening to a playlist that Beyoncés’s shared with her daughter.

ORGANISATIONAL IMPACT

The success of this project relied on the ability to scale the framework throughout the organization. This was a crucial part of the project from start to finish. Stripe Partners conducted multiple stakeholder interviews in order to understand the organizational context of the challenges but also to engage stakeholders in the project. We also used Slack to share interesting links and provide connection between all the researchers involved across all research streams.

At the end of the project, Spotify hosted a share out session with teams joining in person and remotely. We presented insights based on ethnographic evidence, stories from the field and videos from the diaries and used them as a basis for the final framework. The final session also included activation workshops to get participants to think of immediate takeaways and to apply the framework. The session included ‘office hours’ when anyone from the organization could learn more and discuss the project with the researchers. We created visually engaging outputs in form of posters and also did a video recording of the presentation for Spotify’s archive.

Within Spotify the learnings from the research has had a broad impact across multiple business units and has been internalized deeply into Spotify’s culture.

From an agency point of view, this project was relatively unique in the sense that we were engaging with the client’s stakeholders, teams and other researchers and experts from start to finish ensuring the insights and the framework were relevant and easy to understand. This has allowed us to understand the organization better and have conversations with people working on diverse challenges to help them think through potential implications for their areas and goals. Ultimately, this enabled our work to travel and develop new client relationships.

REFERENCES CITED

Karpik, Lucien. 2010. Valuing the Unique: The Economics of Singularities. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Ulwick, Anthony W. 2016. Jobs to be Done: Theory to Practice.