The thought of conducting a usability study may not excite most ethnographically minded researchers. While usability started out as the practical analysis of interactions with user interfaces, there has been an evolution toward devaluing such studies as more mechanical work. With the industry’s shift in focus from ‘usability’ to ‘user experience’, usability methods can seem small in scope, not to mention dusty and dated. Perhaps they call to mind being in a lab and tracking eye movements, counting clicks and generally working in a positivist rather than interpretivist way.

Ethnography, by contrast, is often considered a more strategic and engaging form of research. Exploring a broader context—not limited to interactions with an interface or device—would seem not only more interesting to investigate, but also to require more complex and nuanced understanding. This approach thus suggests a greater proficiency of the research craft. Usability testing can then be perceived as a lower-level skill that one is more easily trained to do. This often makes it the responsibility of early career researchers, work that one eventually moves on from after they ‘put in their hours’ and advance in their career.

However, we aim to reflect on the value of usability methods in an era where research teams are shrinking and businesses are therefore implicitly devaluing research. We also want to challenge assumptions about usability evaluation; for instance, that it only happens in unnatural environments, rather than ‘out in the wild.’ Or that it is a rigid type of testing that cannot be integrated with other types of research interactions. Let us then turn an ethnographic lens onto the friction between usability assessment and broader, macro research. We wonder: can tactical research, in fact, be strategic?

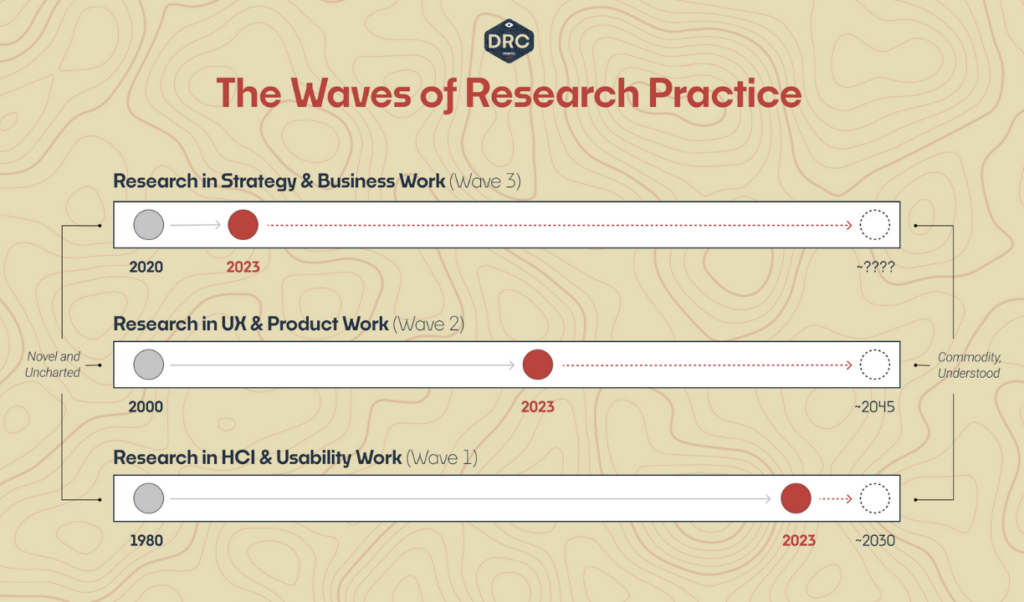

more novel and uncharted approaches (image source)

The usability wave

In his analysis “The Waves of Research Practice”, Dave Hora describes “the usability wave” as beginning in the 1980s and now “nearing diffusion into the background of our work.” Its ideas and practices are largely well understood and adopted. Moreover, they are made accessible to non-researchers or ‘People Who Do Research’ with the advent of testing platforms like UserTesting, UserZoom, etc. With such tools, anyone with a prototype or product can collect feedback and thus appear to do research very quickly.

Has this democratization of usability evaluation diluted the skillset, making it seem lower status for researchers? Potentially. But there are a constellation of other factors shifting how researchers feel about usability assessment. It may relate to encounters with a lack of research maturity, for instance, when a stakeholder assumes that usability testing is the extent of what a researcher can offer. Alternatively, it could be the nature of where usability evaluation fits into the product development lifecycle, often a more reactive rather than proactive approach to research.

Or it simply may be the fact that usability work operates within well-defined or bounded parameters. This results in prescriptive rather than descriptive outputs that may be less generative and open-ended. Usability evaluation’s clear connection to actionable recommendations may not be as imaginative and exploratory for the researcher, but it requires less cognitive load for teams to interpret and implement.

Unfavorable macroeconomic conditions

The straightforward recommendations arising from usability testing are salient and readily applied to product decision making. It is this lack of ambiguity that makes usability research particularly impactful when budgets are trimmed back, no longer awash with cash to hire and retain researchers. In light of impacts to research teams across the industry, what might we make of usability testing’s cultural shift? We hypothesize that this devaluing of usability practice has been detrimental to the research profession. By veering too far into topics that might be conceptually rich but not tangibly applicable to products and services, we may have seemed more disposable to decision makers.

When a study has no immediate recommendations, impact is assessed somewhat obliquely by how often it is referenced or cited by other researchers. As Stripe Partners’ new research playbook puts it: “Research is consumed and discussed largely by researchers rather than product decision makers, amplifying the impression of a siloed [group] of specialists.” So how can we ensure research is more than a theoretical exercise, meaningfully disseminated and absorbed by others? “It’s not just through upstream, strategic work that researchers can shine,“ the playbook notes. “Ambiguity can also be located in more ‘tactical’ usability work.” For example, usability methods can demystify the outcomes of A/B tests or the observations of data science.

In his thoughts on “the UX research reckoning”, Judd Antin outlines a framework of macro, middle-range, and micro research. He argues that we spend too much time doing middle-range research—”a deadly combination of interesting to researchers and marginally useful for actual product and design work.” As Antin puts it, “Low-level, technical UX research isn’t always sexy, but it drives business value. When research makes a product more usable and accessible, engagement goes up and churn rates go down. Companies need that for the bottom line. Users get a better product. Win-win.”

Beyond the what of communicating usability findings, there is also the matter of how they are communicated. Usability evaluation—for better or for worse—often results in numbers that stakeholders latch on to and track. But when contextualized with other qualitative details, this can perform quantification while productively destabilizing a tendency to over-index on metrics. As with the ethno-mining approach, “The appearance of numeric data gets us ‘in the door’, but the insights from ethno-mining provides us with a continuous place ‘at the table’.” As anderson et al write, “By having the appearance of capturing ‘real’ data, [ethno-mining] affords the opportunity to share its messiness, allowing for a co-creation of interpretation in corporate meetings.”

Enhancing the impact of usability at Atlassian

At Atlassian, we have not always had the easiest relationship with usability, perhaps evidenced through our product experiences. Historically, we found unmoderated usability testing platforms to enable problematic behavior. Due to a lack of researcher headcount, unmoderated usability evaluation had become the default research method. The culture was also centered on justifying design decisions with numbers, so such testing enabled the gathering of evidence to proceed with planned work. The unmoderated testing platform thus became a hotbed of cherry picking favorable data points, rather than actually assessing with the mindset of improvement.

“Even if you were skeptical about the unmoderated research quality, you were beaten down with the argument that any data is better than no data,” recalls one researcher, reflecting on the culture at the time. This led the research team to stop supporting unmoderated usability testing at scale, perhaps somewhat unusual for an organization of our size.

We had also observed an organizational attachment to the Net Promoter Score (NPS) metric, and the light version of the Usability Metric for User Experience (UMUX-LITE). We have since encouraged movement away from these measures and instead toward customer satisfaction (CSAT) and the Single Ease Question (SEQ). This has been a shift not only in metrics but also approach—SEQ is more immediate in helping teams understand how they are tracking for usability in a focused area. Ongoing CSAT reporting, by contrast, illuminates the overall health of our products, enabling assessment of a change’s broader impact. Together, these metrics effectively create a ‘learning feedback loop’. This evolution has reduced reliance on numbers of questionable provenance and elevated the rigor of research throughout the organization.

ripple effects (image source)

The SEQ measure in particular has been increasingly effective in holding teams accountable to a quality bar for experiences. In one instance, unacceptably low usability scores for critical product tasks were impactful enough to delay a high-profile launch. We have therefore developed and implemented training, templates, and office hours to scale consistent SEQ usage and guide all those who do research at the organization, beyond those with official researcher titles.

Given our focus on moderated usability testing, we find that it can often result in findings that expand beyond the original scope of research, so long as we remain open to it. For example, even an interface can reveal friction between colleagues—say, a software’s administrator and its end user. Moreover, it can highlight the conflicting usability challenges of different user segments, such as teams in small and medium sized businesses versus those in large enterprise organizations. Such contrasts can thus guide prioritization and other strategic discussions.

While we have primarily expounded on usability research here, let us be clear that researchers at Atlassian take both micro and macro perspectives. After all, if an organization only did usability testing, it would likely struggle to identify emergent market trends and develop new offerings. However, we look beyond the status of usability methods to see instead how they leverage the interface as a provocation—to prompt interaction and participation, often leading to insights much broader in scope.

Many thanks to Ann Ou, Gillian Bowan, Natalie Rowland, Neelam Sheyte, and Sharon Dowsett for their thoughtful input on this post.

Atlassian is an EPIC2023 sponsor. Sponsor support enables our annual conference and year-round programming that is developed by independent committees and invites diverse, critical perspectives.

0 Comments