This case study offers strategies for navigating internal frictions within research teams faced with sensitive issues around positionality, research design, and data collection. Co-authored by junior and senior members of a design-research organization, it describes friction that arose when junior researchers proposing to expand the sex and gender options on a data collection tool. This proposal blossomed into a larger debate for the organization. The case study traces how the organization navigated this friction, outlines the literature they used to anchor their debate, and summarizes the language and practice standards ultimately adopted by the team. The months-long process was complex and challenging, particularly within an organization that valorizes transparent, collaborative, and human-centered decision-making. We believe this case study, showcasing the researchers’ efforts to navigate these sensitive issues, holds value for other researchers and organizations negotiating not just specific demographic terms, but differing understandings of roles and identities held by early-career and late-career researchers.

INTRODUCTION

The Public Policy Lab (PPL) is a nonprofit design studio that works to improve public policy and services. Iteration and innovation are core values of our project work, and we also apply the same approaches internally, using workshops and biweekly all-team meetings to collaborate on big decisions as a group. So when a junior researcher questioned how we capture information about research participants’ gender during our research engagements, this investigation of our status quo felt commonplace. The subsequent nature and breadth of our internal friction, however, pushed our organization into a challenging but ultimately productive engagement around the meaning and intentions of our research practices.

Our junior researchers were in agreement with one another that we should alter the terms we use to describe gender, while our senior researchers sought to open up a wider conversation about the motivations and values of our data-collection processes. We grappled with what type of infrastructure we could create to advance these multiple points of view in a productive way, while also trying to get to mutual understanding about each school of thought. Ultimately, we developed a new framework for demographic data collection that speaks to all of our team’s interests, while not seeking to smooth or buff away a friction that’s fundamental to the differing worldviews of our team members.

PRE-EXISTING PRACTICES

Our demographic questionnaire is part of a multi-step data-collection process that PPL has iterated on often over the years. The process begins with the researcher explaining the background and goals of the project to a potential participant, as well as informing them about the benefits and possible risks of taking part. We then go through a series of consent questions that allow participants to opt in or out of various types of data-sharing. Participants can agree to our researchers recording the conversation for the sake of note taking and transcription on one line, for example, but then opt “no” for that audio recording being used for quote soundbites. We believe this type of fine-grained consent shares power with the participant and gives them increased agency in the interaction. After we’ve conducted these steps, we dive into the meat of the research engagement, which could use a variety of methods, from a semi-structured interview to a co-design workshop.

After we’ve completed the research activities, we come back to the consent form and ask the participant if they want to make changes—for example, if a participant ended up sharing a very personal story and would like to revoke the ability for us to quote them directly. Once the participant has edited or re-affirmed their consent answers and reviewed any photographs we’ve taken, we then ask them to fill out a short demographic questionnaire. We explain to participants that we administer this questionnaire to ensure that we’re speaking to a diverse sample of participants that’s reflective of the populations relevant to our project area. We also inform them that all questions are optional. The questionnaire fits on a single sheet of paper and asks participants to indicate their age range, racial/ethnic background(s), gender, income quintile, and education level. The provided race and gender options align with the U.S. federal census, with the addition of a “prefer to describe” open-ended option. This sheet, or one question on this sheet, was the source of our organizational friction.

DIFFERING PERSPECTIVES

Friction began when a junior researcher took issue with one of the questions on the demographic questionnaire that asked research participants “What is your gender?” Participants could select from one of three answers: male, female, prefer to self-describe. The junior researcher proposed that these answer choices were inaccurate, as male and female were sexes assigned at birth, not genders. The junior researcher also argued that there were many other genders, besides man and woman, that should be included as options on the survey. The junior researcher spoke to other junior researchers and prepared a memo explaining their perspective and proposing an expanded list of gender terms.

A senior researcher was concerned that the specific issue of terminology for gender was too narrow, in that it didn’t engage with the intended purpose of PPL’s demographic data collection. PPL began collecting demographics of research participants to compare against the baseline user data collected or used by service providers and/or government partners (or, absent any service-specific baseline data, to publicly available data sets such as the American Community Survey). The purpose of this comparison is to both understand if our research sample is broadly representative of service users and to also explain our sample’s make-up to project partners. Many of PPL’s government partners (and government data sets) do not collect information on gender categories beyond man and woman; PPL also uses many other similarly broad demographic categories (e.g., “Asian” or “65+”) that elide significant experiential differences among people who fall into that defined category. Was the junior researchers’ interest in collecting sample data to compare against population data? To advance research best practice by asserting new norms for demographic categories—limited to gender or more broadly? Or to provide identity validation to respondents and researchers?

These questions did not lead to a coming together around a shared viewpoint—rather they intensified a sense of difference and missed connection between the junior and senior researchers and led to the refinement of new claims. The junior researchers had three arguments: 1) If the purpose of the demographic data is national standard comparison, there are many national standards that acknowledge genders beyond man and woman. New York (the state where our organization is based) birth certificates, New York driver’s licenses, U.S. passports, the Census’s Household Pulse Survey, the National Victimization Survey, the Health Center Patient Survey, and the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems Survey all include an option for nonbinary and transgender people. 2) Demographic data collection serves another key purpose: identity validation for research respondents. Multiple studies demonstrate that LGBTQ+ people feel more comfortable and satisfied with surveys that have gender-inclusive questions, which enable them to accurately select their gender. Junior researchers clarified that their argument had nothing to do with identity validation for researchers themselves and pointed out that their proposal could have just as easily been brought up by researchers who did not identify as LGBTQ+ and the same reasoning would hold true. 3) From a research data perspective, there is value in expanding gender options, as identifying gender-diverse respondents helps PPL understand the unique issues these groups face. This is especially important, because LGBTQ+ people are significantly overrepresented in some of PPL’s research projects (e.g., 40% of youth experiencing homelessness identify as LGBTQ+). The American Journal of Public Health writes that non-representation of transgender individuals in surveys hinders an understanding of the social determinants this group faces.

The senior researcher had differing points of view: 1) PPL’s first responsibility is not to a national standard comparison, but to match our demographic data to our government partner’s data, in whatever form they collect it, or to the closest available public data set. If our goal is to make sure we’re speaking to a representative set of our partner’s clients, we need to compare our research respondents directly to that pool of clients, using the characteristics our partners already collect and have available for us. On the junior researchers’ second argument, the senior researcher had a very different perspective: 2) It is not the researcher’s role to validate a participant’s identity nor to necessarily connect with a participant on a personal level, even if the researcher and participant may share demographic characteristics. There are analytical, ethical, and safety advantages to an ‘impersonal’ positionality when conducting research with respondents of highly divergent views and backgrounds (often very different from the researchers themselves) and in reporting research findings to the organization’s partners and funders, many of whom hold very different identities from those of their client populations, with whom the research is conducted. 3) And while PPL has certainly done research that focuses on the experiences of young people, among whom nearly 20% identify as LGBTQ+, we conduct the majority of our work with adults generally, only 44% of whom say “forms and online profiles that ask about a person’s gender should include options other than male and female”—and the remaining 56%, although we disagree with them, are also our respondents.

Just as these polls suggest the existence of different realities, so our junior and senior researchers realized that the friction they were experiencing stemmed from fundamental differences in the way they each viewed a professional researcher’s role. Junior researchers believed that a researcher should prioritize trust-building and personal authenticity between themselves and the research participants—and that the external descriptive categories they apply to themselves and others are never neutral but hold the power to form and alter the social world. Junior researchers pointed out that the purpose of the organization was to serve the American public, especially those who historically have been marginalized, and asserted that a researcher at this organization should therefore choose categories that prioritize a feeling of inclusion for marginalized populations. The senior researcher observed that research is paid labor conducted in a constructed social context in which neither participants nor researchers are their ‘true’ selves—and that a commitment to making researcher and respondent identity totally and mutually legible could be professionally problematic and personally dangerous, given how often professional researchers must engage with curiosity and courtesy even with respondents whose behaviors or beliefs they find alien or even repellent. A constructed neutrality, even if inaccurate, serves as a valuable professional fiction. Collectively, the team decided that rather than continue to grind away at each other’s world views, we’d dive into literature around the frictions associated with researcher positionality and see what insight we could find.

LITERATURE ON RESEARCHER POSITIONALITY

Researcher positionality “describes an individual’s world view and the position they adopt about a research task and its social and political context” (Darwin Holmes, 2020). This positionality is central to all aspects of research, affecting what the researcher chooses to study, how they conduct the research, and what outcomes they find (Malterud, 2001, Grix, 2019, Rowe 2014). A researcher’s positionality is influenced by their personal characteristics, such as their gender and race, as well as their fluid subjective experience (Chiseri-Strater, 1996). We explored several approaches in the literature to understanding and responding to researcher positionality.

The longstanding idea of emic or etic positionality originated in the linguistics field and was imported into anthropology in the 1950s (Mostowlansky and Rota, 2020). Emic and etic refer to two different ways of conducting/viewing research and offer a frame for considering a researcher’s relationship with or to their respondents. The emic, or insider, position is about “grasping the world according to one’s interlocutors’ particular points of view.” Meanwhile, the etic, or outsider position, aims to “establish an objective, scientific approach to the study of culture” (Mostowlansky and Rota, 2020). Superficially, these two positionalities might seem to track with an ‘insider’ approach taken by our junior researchers and an ‘outsider’ positionality posited by our senior researchers—but our own experience, like that of many researchers, was a more nuanced combination of both.

In one case study, linguistic ethnographers working in elderly care facilities in Sweden interrogated their relationships with research participants, investigating whether an emic or etic identity served them better (Jansson and Nikolaidou, 2013). Ultimately, they found that this dichotomy was overly simplistic and that, while they initially viewed themselves as outsiders working towards an insider perspective, they realized that an outsider positionality was never fully possible: “all researchers are close to their research participants in one way or another” (Jansson and Nikolaidou, 2013). The researchers realized the value in embracing and understanding the ways that their identities interacted with the participants’ identities: “It was through unravelling the institutional, professional, and individual aspects of their identities, but also through opening up our own selves and our own identities that we gained their acceptance. In other words, it can be argued that ethnographic work at its best took place only when we started negotiating who we were in relation to the research participants and vice versa.” (Jansson and Nikolaidou, 2013). At PPL, the senior researcher had found, again and again, that she had some of the most profound experiences of mutual understanding with research respondents with whom she shared few demographic or experiential similarities. The junior researchers also observed that when they conducted research with members of the public with whom they shared many identity characteristics, they often learned about ways that participants’ identities interacted with the environment in different ways, producing experiences that were different than the researchers’ own experiences.

Ultimately, as Jansson and Nikolaidou found, the emic/etic debate may be a false and outdated dichotomy. Researchers inherently occupy the positions of both the insider and the outsider and there must be space for this nuance to be examined. Further, what constitutes a ‘culture’ is not firmly bounded, so it’s not always easy to say when one is ‘outside’ or inside.’ In their paper “The Space Between,” Dwyer and Buckle examined their positionality to their research participants. While Dwyer entered the research as an ‘insider,’ interviewing other white parents of children adopted from Asia, and Buckle entered the research as an ‘outsider,’ interviewing parents who had lost their children which Buckle had not, both found themselves occupying a space between. Dwyer found that she shared experiences and opinions with some of the parents she interviewed but not others; meanwhile, Buckle found that though she did not know the loss of a child, she could relate to her research participants around the experience of loss and grief. The authors write, “Surely the time has come to abandon these constructed dichotomies and embrace and explore the complexity and richness of the space between entrenched perspectives” (Dwyer, Buckle 2009).

For more than four decades, it’s been best practice in human-research fields for researchers to engage in reflexive consideration of their own positionality. Reflexivity “suggests that researchers should acknowledge and disclose their own selves in the research, seeking to understand their part in, or influence on, the research” (Cohen et al., 2011). Reflexivity does not mean that the researcher is completely removed from the research, but rather that they are discussing and thinking critically about the way their position affects their work. The process of reflexivity can be difficult and time-consuming, especially for novice researchers, who may struggle with identifying and understanding their positionality (Darwin Holmes, 2020). A narrowly reflexive approach may also have the unintended effect of focusing too much attention on the researcher’s own identity and positionality, in lieu of highlighting the reciprocal creation of shared knowledge that is a core feature of respectful human research.

While reflexive practice is an individualist approach to interrogating researcher positionality, an alternative and collective model is offered by professional and organizational codes of ethical conduct. Professional associations such as the American Anthropological Association (AAA) and the Association of the Social Anthropologists (ASA) in the United Kingdom detail standards for the behavior of researchers that are agnostic to the positionality of the researcher. Per these codes, all researchers should seek to “maintain respectful and ethical professional relationships” and to be mindful of the “real and potential ethical dimensions” of their engagement in “diverse and sometimes contradictory relationships” with their collaborators (AAA). As noted in the ASA guidelines, “concerns have resulted from participants’ feelings of having suffered an intrusion into private and personal domains, or of having been wronged, for example, by acquiring self-knowledge which they did not seek or want” (ASA). The obligation of the researcher, these codes remind us, is not solely (or even primarily) for the researcher to understand themselves, but for the researcher to notice and minimize the potential negative effects of their research even as they seek to understand some aspect of their respondents’ experience.

Ethical codes can serve to protect both respondents and researchers from bias and from the intimacy and exposure — and subsequent risks — that human research can engender. Indeed, researchers may find themselves at risk when interacting with participants. One anthropologist recounted how during fieldwork in Nigeria, the research dynamic of participants sharing vulnerable stories about themselves created an inherent expectation of reciprocity that she would compensate them with a small gift, money, etc. Some of the male research participants she spoke to expected that she would compensate them through sexual favors, exposing the anthropologist to dangerous, risky situations (Johansson, 2015). In more than a decade of conducting and overseeing research at PPL, the senior researcher observed many instances where our engagements with Americans dealing with poverty, homelessness, mental illness, and other challenging situations led to feelings of intimacy, responsibility, and expectation—both on the part of researchers towards respondents and also from respondents towards researchers—that felt ethically and emotionally difficult.

NAVIGATING THE FRICTION

Creating a Friction Resolution Road Map

One of PPL’s defining characteristics is the way we embrace iteration, both in our project work and in our internal organizational work. We change elements of our research practices often, make edits to materials, alter protocols, and have even overhauled our pay scale based to respond to management aspirations, employee proposals, and all-team discussions. This is not to say that we are immune from the discomfort that often accompanies friction, but we are familiar with it, and we have systems in place to move through it. This case, however, felt particularly fraught—maybe due to the differing generational perspectives, the highly personal subject area, or because of the political moment in which it was ensconced. Both cohorts identified these factors quickly and knew that we would need to design a new system to navigate it. Together, interested team members formed a working group to design a path to conflict resolution. This working group was a mix of seniors and juniors, who, although having conflicting viewpoints on the specifics of the questionnaire, were mutually committed to forging a new path forward that felt, if not good, at least acceptable to all involved. Their plan included two loosely-facilitated discussions between project staff, and then three larger discussions with the full organization. We also utilized a few artifacts and stimuli to ground our conversations.

The two non-senior sessions took place during standing research meetings. These sessions gave junior researchers a space to gather their thoughts and clarify their arguments in the absence of senior leadership. This felt particularly important because many of the organization’s junior researchers identify as queer and gender diverse and, given that this friction struck a personal chord for them, they craved space not only for discussion, but to feel heard and validated by others with similar identities. During the sessions, junior researchers discussed why they believed the questionnaire should change, proposed new alternatives, and aired out their feelings about how this debate was impacting them personally. This first non-senior session was an open-ended discussion, while the second session was spent reviewing precedents, compiling comparison research materials in a collaborative document, and clarifying what junior researchers believed to be the ideal updated version of the demographic questionnaire.

With a clearer consensus among the junior researchers of how they wanted to frame the argument and what their ideal outcome would be, we moved into the second portion of discussions, this time with the full team. In the same way that the junior researchers had a moment to clarify their argument, the working group similarly asked the senior researcher to write out her thoughts in a succinct document that the team could review and digest on their own before debating in real time. The senior researcher’s “13 theses,” as they came to be jokingly called, were circulated among the team a few days ahead of our first all-team session (though not nailed to the door). The first nine theses made claims about the broader topic of researcher positionality and its proposed role in PPL research practices, while the latter four theses addressed the topic of the demographic questionnaire specifically. The senior researcher asked the entire team to review the theses and write their responses, critiques, questions, and discussion points in a collaborative document to serve as anchors during the full-team discussion. Asynchronous back-and-forth about each of the theses turned the “13 theses” document, which was originally five pages, into a 15-page document, which the team referenced and further expanded on during and after team-wide discussions.

Team-wide Discussions

The first full-team discussion focused on the first nine theses, centered on research positionality. The theses are roughly summarized as follows: the purpose of the organization’s qualitative research is to fuel invention – to harvest people’s experiences from them and use those stories to make things – which make the research necessarily extractive. At the same time, the researcher has a moral responsibility to limit unforeseen or undisclosed harm to the research participants and ensure that the research is not exploitative. This balance – between a practitioner’s functional work requirements and their moral responsibilities toward people on or with whom they conduct their paid work – underpins researchers’ informed consent procedures and positions the researcher as what they are: a paid and intentional producer of knowledge, operating in a professional capacity. Researchers must be transparent and open about their role, carving out an interaction space that suspends normal social rules and allows for unusual candor on the part of the participant and a suspension of judgment on the part of the researcher. This is not the same as cruelty or carelessness—and this does not, in any way, indicate the suspension of critical analysis. If a genuine consent process has been carried out beforehand, this interaction space is something that the participant has agreed to – and the researcher must respect the participant’s agency in this choice. Of course, the unevenness of this interaction will lead to a build-up of emotion and opinion in the mind of the researcher, which can be harvested post-engagement in the debrief and which can serve as a wellspring for personal and professional growth (though that may not feel easy or safe).

Junior researchers primarily took issue with three of these tenets – (1) that research is inherently extractive; (2) that researchers can or should form professional identities distinct from their personal identities; (3) and that researchers can or should withhold emotions during the research engagement until the debrief – opening up subsidiary discussions that went over the allotted meeting time, because everyone had different viewpoints they wanted to express. Many team members (both junior and senior) shared examples from their experiences as researchers, as research participants, and as people who inhabit many overlapping identities. As the conversation progressed, there was also meta-commentary and critique about the way the conversation was being conducted and how team members thought experiences should be handled. One junior researcher wrote on the Google Doc, “Also (because we ran out of time), in this conversation I’ve observed taking people’s experiences into account as “potentials” or “maybes” and I think when people share their experiences it should be acknowledged that they are experts in their own identities… [I] wanted to acknowledge the historical and cultural weight of this, especially when so many of our BIPOC researchers were sharing their experiences in comfortability in research.” The senior researcher replied, “Institutionally, the PPL is not going to engage in any ranking or comparative valuation of people’s past bad things—nor can the organization even assess the weight of any bad thing in its own self…You may choose to share your past life experiences at work, if you so desire, but your choice to disclose should be undertaken without any expectation that it compel actions or feelings on the part of your colleagues.” After the discussion ended, team members continued to reflect on this dialogue, to sit in the discomfort of their differing viewpoints, and to consider the viewpoints of other members of the team.

The second full-team discussion occurred two weeks later and focused on the latter four theses, which outlined the senior researcher’s theories of how researcher positionality informs the demographic questionnaire, summarized as follows: the questionnaire is intended to help the organization demonstrate how its research respondents are reflective of the system/community it is investigating. More specifically, researchers may compare the demographic data of a research population to baseline data about service users to demonstrate that their sample is broadly representative, they may use demographic data to report on which demographic factors correlate with which service experiences, and they may use demographic data as a contributing storytelling device to position qualitative findings in the context of observable characteristics. Finally, the proposal to alter demographic categories to be more inclusive of participants’ gender identities raises a number of questions. These questions, which constitute the thirteenth thesis, are listed below.

13.1. How might the inclusion of additional defined choices for gender identities improve our ability to use respondents’ demographic data for the comparative purposes described above?

13.2. Can we weight the utility of using defined (multiple choice) demographic options for gender identity vs. the value of using an open-ended question that allows respondents to frame their answer in their own words?

13.3. What are the trade-offs around PPL seeking to maintain a standardized list of defined choices for gender identities that is consistent across all PPL projects versus shifting to developing a unique questionnaire for each project?

13.4. How might the inclusion of additional defined choices for gender identities generate distrust or discomfort among some respondents, even as it creates trust and comfort for others? E.g., by including more specific and close-ended gender categories, what feelings might we generate among respondents with cultural or religious commitments to binary gender identities?

13.5. How should we navigate tensions around safety, privacy, and/or divergence between interior awareness and external perception? E.g., by making our gender categories more specific and close-ended, are we asking people to ‘out’ themselves?

13.6. How does the inclusion (or non-inclusion) of additional defined choices for gender identities suggest a positionality or judgment on the part of PPL researchers regarding respondents’ gender identity?

13.7. Do PPL researchers have strong personal beliefs around the inclusion of additional defined choices for gender identities that are external to PPL’s research needs? What opportunity does that present for reflexive investigation around the relationship of personal identity to professional identity?

13.8. What might our discussion of all of the above suggest about the framing of our questions that seek information on people’s racial/ethnic identities, their age, and their class position (as reflected by income and education level)?

This second team workshop had a different tone than the first workshop. While junior researchers still disagreed with some of the tenets of the senior researchers’ theses – e.g., junior researchers argued that the demographic questionnaire should serve to not only demonstrate how the research sample is representative but also validate research respondents’ identities – they had a better understanding of the senior researcher’s perspective. The questions from the senior researcher’s 13th thesis served as a launching point for the team to evaluate the demographic questionnaire as a whole. As the team confronted different answers to the 13th thesis’s questions and struggled to come to a conclusion of how to rewrite the gender question – e.g., for 13.5, junior researchers argued that gender-diverse options were not asking anyone to ‘out’ themselves, but were just making space for different identities, while the senior researcher continued to hold privacy and safety concerns about collecting non-binary gender data with and for government agencies – the juniors researchers also came to understand the senior researcher’s view that this same scrutiny could be applied to the other questionnaire questions. For example, how did the organization decide how to group different racial groups together or different age groups together? Furthermore, how did the organization decide which demographic questions to ask in the first place? The team began discussing alternative ways to frame the demographic questionnaire, the questions on it, and the categories of the answer choices. Both junior and senior researchers agreed that the survey needed to have a clarified process behind it.

Preliminary Outcomes

Junior and senior researchers ultimately decided that a one-size-fits-all demographic questionnaire no longer met our needs as an organization. Our demographic questionnaire needed to be tailored to each specific research project. First, each project has different project partners who have different baseline data. In order to demonstrate that the research sample is broadly representative, the demographic survey should collect data that is as similar as possible to the data that partners routinely collect. Second, each project studies a different system user population. In order to observe if demographic factors correlate with service experiences, the demographic questions should be tailored to capture the characteristics of the population in question. For example, for a project studying the healthcare experiences of older Americans, it would not make sense to use the standard age categories of “18-24; 25-34; 35-44; 44-54; 55-64; 65- 74; Over 75.” Rather, it would make more sense to begin the answer choices with 65 years old and incorporate more granularity, e.g., “65-70; 70-75; 75-80; 80-85; 85-90; 95-100; 100-105.”

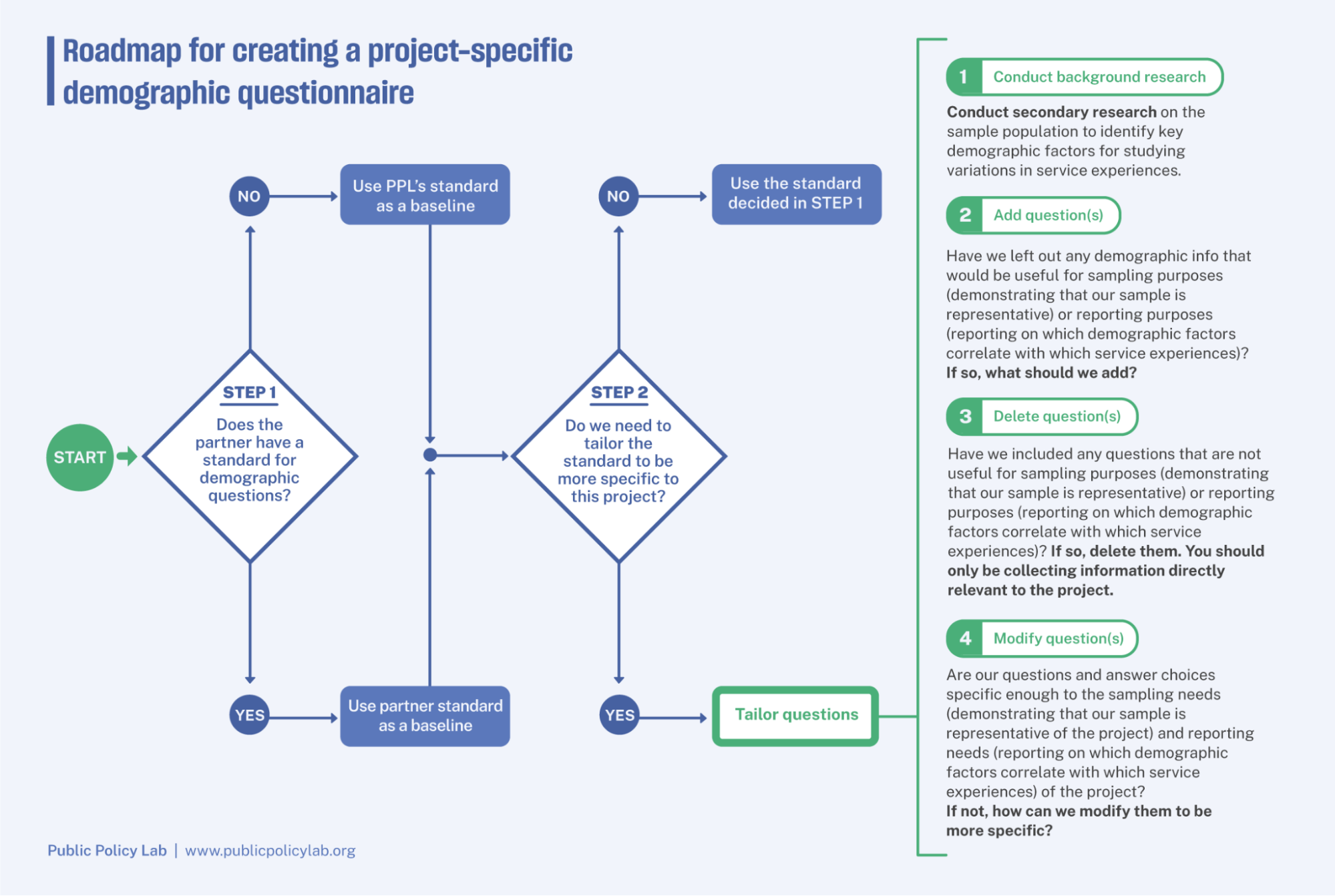

The team worked together to create the following weighing tool, which can be used to tailor the demographic questionnaire to each project.

What does this mean for the gender question? There may be some projects in which the gender question is completely omitted if the partner agency does not routinely collect information about service users’ gender and if it is not germane to what the project is studying. There may be projects in which the question is included and the original options of “male,” “female,” and “prefer to self-describe” are offered if participants’ gender is relevant to the project and partner agencies offer only a couple of options for participants to identify their gender. Finally, there may be projects in which the question is included and additional answer choices are offered, such as “transgender” and “two-spirit,” if a large proportion of the population being studied identifies as LGTBQ+ and Native American, and identifying these respondents will help researchers study correlations between participants’ gender identities and their service experiences.

Since developing the demographic weighting tool a few months before completion of this paper, researchers have applied it to two projects. In both of these projects, our project partners had data collection categories that differed from our initial baseline. We were also working with subsets of the populations whose nuance would have been lost had we not tailored our categories to capture them specifically. In this way, our new tool and protocol was proving to be successful not only in assuaging the concerns of our internal team members but also in improving the quality of our research.

WHAT WE LEARNED

From the time the junior researcher first proposed a change to the demographic questionnaire to the time that the new weighting tool for demographic questionnaires at the organization was piloted, nine months passed. Through this lengthy process of recognizing differing viewpoints, understanding the origins of opposing perspectives, identifying a path forward, engaging in team-wide conversations, and creating a new tool together, the team learned many key lessons about navigating friction. From this experience, we’ve identified eight considerations that may prove helpful for future organizations or researchers who find themselves in similar situations.

1. Make the conversation tangible

Anchor the friction in something that the team can respond to directly. This can be in the form of some sort of design stimuli, a written proposal, a set of theses, an activity, etc. Having a concrete document to reference, build off of, and return to will keep the conversation grounded and prevent conversations from straying too far from the objective.

2. Contextualize the friction

Research how the friction at hand fits into conversations in the literature, conversations that the team has had in the past, and conversations that other organizations and researchers have had. Context helps the team gain a more balanced understanding of the core of the friction and figure out ways to move forward.

3. Don’t rush to a resolution

Though friction can be uncomfortable, it is a useful opportunity for a team to critically examine its practices and consider new ways of doing things. Make sure that group discussions are spaced out and that team members have time to breathe, process on their own, and prepare for the next engagement. Friction is rarely just about what it seems like on the surface, and taking the time to interrogate the deeper paradigms behind different perspectives can be very fruitful.

4. Create a friction resolution roadmap

Create a roadmap for how the friction will be resolved and designate one person or a group of people on the team to oversee the conflict resolution process. Make sure all team members are aware of the steps of this process and be transparent as the process evolves.

5. Acknowledge power imbalances

Assess power dynamics within the friction and create an infrastructure that responds to them and attempts to redistribute power, such as by having a junior-only discussion before engaging with senior leadership or providing time for senior leaders to respond in writing.

6. Create an infrastructure of support

For members of the team who have experienced violence and victimization, friction may be triggering. Find ways to incorporate trauma-responsive practices, such as creating space for discussing power imbalances and allowing team members to opt out of conversations. Let team members know that there are resources and support available for them if they need it, and ensure that there are opportunities for community-building and co-worker support. No one wants to feel they’re navigating friction on their own—even participants who may have institutional power.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Nia Holton-Raphael is an ethnographer and design-researcher. She currently works at the Public Policy Lab as a design research analyst. They received their bachelor’s degree from Barnard College of Columbia University in Urban Studies and Architecture.

Chelsesa Mauldin is a social scientist and designer with a focus on government innovation. She founded and directs the Public Policy Lab, a nonprofit organization that designs better public policy with low-income and marginalized Americans. She is a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley and the London School of Economics.

Meera Rothman is a researcher, strategist, and writer with a focus on health equity for marginalized populations. They earned their master’s in Health Policy, Planning & Financing at the London School of Economics and studied Ethics, Politics & Economics during their undergrad at Yale.

NOTES

The authors would like to acknowledge the thoughtful contributions and feedback provided by Jordan Kraemer.

REFERENCES CITED

“ASA Ethics Guidelines 2011,” American Sociological Association, https://theasa.org/ (accessed October 11, 2023).

Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth. “and Reflexivity in Case Study and Ethnographic.” Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of 115 (1996).

Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. Research Methods in Education. 7th Edition. London: Routledge, 2011. doi:10.4324/9780203720967.

Dwyer, Sonya, and Jennifer Buckle. “The Space Between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8, no. 1 (2009) doi:10.1177/160940690900800105.

“Ethics Statement,” American Anthropological Association, https://ethics.americananthro.org/category/statement/ (accessed October 11, 2023).

Galperin, Bella L., John H. Sykes, Betty Jane Punnett, David Ford, and Terri R. Lituchy. “An Emic-Etic-Emic Research Cycle for Understanding Context in Under-Researched Countries.” International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management 22 (2022).

Grix, Jonathan. The Foundations of Research. Sydney: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Holmes, Andrew Gary Darwin. “Researcher Positionality – A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research – A New Researcher Guide.” Shanlax International Journal of Education 8, no. 4 (2020): 1–10.

Jansson, Gunilla, and Zoe Nikolaidou. 2013. “Work-Identity in Ethnographic Research: Developing Field Roles in a Demanding Workplace Setting.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods Volume (2013).

Jeffrey M. Jones, “Number of LGBT Americans Remains Steady,” Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/470708/lgbt-identification-steady.aspx (accessed October 11, 2023).

Kim Parker, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, and Anna Brown, “Americans’ Complex Views on Gender Identity and Transgender Issues,” Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2022/06/28/americans-complex-views-on-gender-identity-and-transgender-issues/ (accessed October 11, 2023).

Malterud, Kirsti. “Qualitative Research: Standards, Challenges, and Guidelines.” The Lancet (London, England) 358, no. 9280 (2001): 483-488. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6.

Medeiros, Mike, Benjamin Forest, and Patrik Öhberg. “The Case for Non-Binary Gender Questions in Surveys.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53, no. 1 (2020): 128–135. doi:10.1017/S1049096519001203.

Meerwijk, Esther L., and Jae M. Sevelius. “Transgender Population Size in the United States: A Meta-Regression of Population-Based Probability Samples.” American Journal of Public Health 107 (2017): e1-e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578.

Mostowlansky, Till, and Andrea Rota. “Emic and Etic.” In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein, facsimile of the first edition in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 2023. http://doi.org/10.29164/20emicetic.

Rowe, F. “What Literature Review Is Not: Diversity, Boundaries and Recommendations.” European Journal of Information Systems 23 (2014): 241-255. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.7