This paper argues that more appropriate measures are needed to illuminate the full value to organizations of investing in ethnography. The author proposes a framework for defining qualitative and quantitative variables for impacts that unfold across both short- and long-term horizons, and through direct and indirect outcomes that are financial, organizational, and strategic. The author also argues that these variables must be defined in ways that are meaningful to both the organizations we work for and the communities they interact with. A case study of a past project demonstrates the multidimensional return on ethnographic investment.

Introduction

A perennial challenge for ethnographic researchers is to demonstrate the impact of our work. Whether it’s a bullet point on a resume, a case study in a portfolio, or a talking point in a budget request, we’re asked to describe the value our work brings to the business bottom line. Numbers drive the business world and while it is wise to speak the language of business, I want to challenge us as ethnographers to apply the same thinking we use in doing our research to defining our value to organizations in a more robust way. The output of ethnographic research cannot be reduced to a neat and tidy equation that generates a number that moves up and to the right.

A few years ago, Chad Maxwell challenged EPIC members to stop justifying and defending our work: “I’m done with that. I want all of us to be done with that. I want us to sit in a position of the offense and unapologetically show our craft, our approach, yields true, measurable impact, and unapologetically move forward with that” (2021). This essay is my attempt to help all of us do just that. In the spirit of looking back to move our discipline forward, I offer a framework to help us view our work in terms of return on ethnographic investment without being limited by financial measures. Because my specific focus is ethnographic research, the framework outlined here may not apply in every case as not every research situation or business context calls for an ethnographic lens. Conversely, for readers who are not ethnographers, I offer this—if you are investing your human capital into understanding and solving human problems through multi-method approaches, incorporating observation and a mix of structured and semi-structured methodologies, what I outline here likely still applies.

“Return on investment” (ROI) is a success narrative that uses quantitative measures which can be easily converted into financial impact—improved conversion rates, increased customer base, profit, decreased error rates, saved time. None of these results happen through magic. They are the result of planning, evaluation, and tough choices. They are the result of dedicated people driving towards a goal. When ethnographers are engaged, our work comes early in the process and our qualitative insights are cautioned as “directional,” as if direction isn’t precisely what is needed for developing strategic vision and setting goals. This ROI narrative is so powerful that we’ve convinced ourselves of the imprecision of the value we deliver. We often search for more precision in speaking about and calculating ROI than we need to in order to create our own success narrative of ethnographic impact.

The framework I offer is a narrative framework that doesn’t preclude ethnographers from offering a quantitative financial measure of our impact. Instead, I push us to understand which measures matter in both the short- and the long-term, acknowledging that these measures may not be the same. To truly measure impact, we cannot over index on short-term impacts and I invite us to reflect on how our impact unfolds over time as more than the sum of its parts. I begin with a reflection on a 19-year-old study to ground us in ethnography as the heart of the framework. While ancient history in business terms, enough time has passed to see both the tangible and intangible effects of this work and illustrate a more robust range of longer-term impacts that ethnography can bring to organizations. Following the reflection, I offer some myth-busting around traditional ROI and dig into how ethnography adds value beyond the short-term by preparing organizations for change through attention to liminal spaces and relationships. Finally, I offer my framework for how we can estimate the value of our work, encompassing both immediate impact and long-term impact, as well as sustainable impact, which is the amplified value we bring through insights and recommendations that foster greater organizational resilience.

Reflection on Habitat Charlotte Communities

In Spring 2006, I led a consultation project with Habitat for Humanity of Charlotte (Habitat Charlotte) which initially sounded simple—how can Habitat Charlotte make townhomes appealing for homeowners (Metzo 2008)? Given that I was using the project to train a group of students, a comparative study of Habitat affiliates already building townhomes made sense. Through multiple rounds of discussion with stakeholders, we learned more about the problem this solution was meant to address. Land values were rising rapidly in Charlotte—infill lots cost 10 times in 2005 what they cost in 1983[1]—but Habitat Charlotte wanted to sustain, if not grow the number of homes they were building each year. The root problem for these stakeholders was whether they were truly fulfilling their mission if service remained flat, or worse, declined.

The biggest surprise for us was that the organization had not talked to their own homeowners, so we did. While one group continued with interviews and site visits with other Habitat affiliates, a second group supported me in facilitating workshops with homeowners. We broke the workshops into 4 sections. The first three sections started with quiet reflection on a prompt before sharing with the group while the fourth section revealed townhomes as a proposed alternative to detached, single-family residences and asked which items on each list were most important in that context. The three prompts invited participants to imagine the interior, exterior, and neighborhood for their “ideal home.” We ended the session with open discussion of criteria the staff and board should keep in mind as they identified ways to sustain their mission of building homes.

While we “validated” that townhomes were “acceptable,” we uncovered more desirable alternatives that also met the financial constraints that Habitat Charlotte was trying to overcome. The idea of a new, single-family detached home was ideal, but based on location and neighborhood, homeowners were willing to consider renovated homes. Both townhomes and renovated homes allowed for greater flexibility in location—closer to family or work, better neighborhood schools, amenities, etc. A root problem for homeowners with the Habitat model was the heavy responsibility they felt to serve as role models in their communities. On reviewing her options through Habitat, one homeowner stated, “I was really pissed—like, ‘how dare you bring me into these areas that are beat down and run down where the city hasn’t done anything to improve the community.”Another homeowner shared a more measured position:“I feel like they are choosing people to put in those communities so that we can become a community and help others . . . I mean they don’t let just anyone into Habitat”(emphasis added). Throughout these emotionally charged conversations, homeowners landed on the idea of building an all-Habitat community–a place where they could more easily turn to each other for moral and material support, feel reassurance that each of the other homeowners went through the same rigorous screening and demonstrated their financial stability and personal responsibility before their selection as a homeowner. In the end, our research insights lead to the development of multiple new programs: Critical Repairs (2007); Townhomes (2008); and Habitat communities (2012).

Figure 1. View at dawn of cul-de-sac on Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter Project build for Meadows at Plato Price community, October 2023, Charlotte, North Carolina. Photo by author.

Why Traditional ROI Doesn’t Work

We are all familiar with the saying “If you can’t count it, you can’t measure it,” and that sentiment is at the core of the concept of ROI. When we choose to assign value to research, as with any other discipline that ultimately supports bringing new products and services to the market, we make some assumptions in order to craft a “measurement” of the output of our work. For User Experience (UX), Forrester (cited in Kucheriavy 2017) boldly asserts a return of $100 for every dollar invested in UX. Establishing this kind of blanket frame for a field that employs a deep bench of ethnographers has not prevented disproportionate layoffs of UX researchers in the early 2020s. Because business runs in quarterly and annual cycles, the myths below are taken for granted as meaningful measures of impact, but if we rely solely on these measures blanket assertions about ROI, we short change ourselves.

I am by no means the first person to offer a critique of calculations of ROI applied to research and this is not meant to be an exhaustive critique. In fact, some ethnographic impact can fit nicely into the traditional ROI assumptions. This more “traditional” model can work for more evaluative types of research and other business functions such as marketing spend, because that work typically comes later in the process and has a more linear relationship to the product or service that is being stood up. Where this model falls apart is when we consider how much ethnographic research directly or indirectly drives strategy, which is not always expected to have an immediate impact on the organization, but should always provide clear direction for longer term efforts. This type of impact is more difficult to measure with a blunt instrument like ROI. For the purposes of this essay, I highlight several key myths of the ROI model: value can always be translated into a financial measure, it becomes apparent relatively quickly, and has a linear relationship to outcomes.

Myth 1: Outcomes Can Be Measured in Dollars and Cents

Most often, we see impact translated into a direct and discrete financial outcome or some other measure that can be converted into dollars and cents. Financial outcomes might include positive revenue from increased conversion rates, for example, or a net savings (e.g., positive margin) from decreased operating or labor costs. Put more simply, we built the right thing and the company makes money or we prevent a costly mistake and save money before building the right thing (and then make money). In design research, “build the right thing” is a truism and while we can never mitigate all risk, great research can bring us closer to the “right” fit as well as building in the ability to pivot quickly with research-based insights. My objective here is not to say it’s never worth the effort of quantifying, only that even when it might fit it is limiting when applied to ethnography.

All research brings financial, temporal, and trust “costs” while the “return” is generally only talked about in terms of a financial benefit. Such measures fail to capture the rich and multi-faceted outcomes of ethnographic engagements. In the Habitat example, rather than a financial measure, the Charlotte chapter uses number of families served (e.g., homes built or restored) as a direct impact measure. So, while I could choose three years as a generous short-term window and define the ROI our research as benefitting over 10 additional homeowners, that doesn’t account for variability of costs for renovation versus new construction or the shifting volunteer needs for adding more two-story buildings. Such a measure would also completely ignore the intangible shift in perspective around creating a nurturing environment for new homeowners to support each other and feel supported by Habitat instead of feeling mostly responsibility for their neighbors. Collecting and counting outputs can never truly add up the human impact that ethnographic research provides by making sense of complex social relations and structures.

Myth 2: Impact Can Be Seen Fairly Quickly

We are generally asked to measure impact on a very short time horizon, but ethnography tends to inhabit different and multiple time horizons. We may have replaced the “ethnographic present” with a more dynamic view of time, extending our research into “futures,” which makes measuring our work against quarterly key results even more challenging. To even provide a rough arithmetic value for the Habitat project, I gave myself three years. What these narrow time views of impact miss are delayed wins and sustainability vs. inadequacy of solutions.

Much of the work within design research is evaluative, fast, and ideally iterative. While this work can be suited to the conventional approach to ROI,[2] ethnographers delivering these kinds of studies will also tap into more fundamental insights around mental models, user values or archetypes, integrating ethnographic practice into more structured methods. Guth (2022) addressed head-on the challenge of “research amnesia,” where insights are forgotten or teams are “ill-equipped” to leverage research insights beyond discrete, time-bound frames. What if we revisited products or services built off of our research several years later to evaluate the staying power of solutions? Just as the knowledge about the communities we study doesn’t “expire” at the end of the study, the impact of our research on future strategic decisions should be celebrated and measured.

Perhaps more troubling with the emphasis on short-term wins is the lack of sustainability in solutions that provide instant returns. Alan Cooper, one of the fathers of user experience, spoke to the emphasis on speed as problematic. He compared tech production to having all the ingredients for making a cake and a specification of an amount of time, but no definition of done. “All we know is that it is on time, but its success will be a mystery” (1999, 42). Consider the front-end experience that gets high marks from users and results in a 30-fold increase in leads. Now imagine this “win” lacks any back-end support for adjusting internal processes, whether technical or labor-related, to convert these leads to sales. Without broader support, a short-term win can plateau or reverse itself.

Myth 3: Insights are Directly Correlated to Business Outcomes

The way ROI is typically calculated is by drawing a straight line from outputs (e.g., research recommendations, design changes) to outcomes (e.g., increased profit, improved customer satisfaction). One reason ethnographers are reluctant to measure impact is that we know how many people and decisions are involved in the journey to a finished product, service, or campaign after our contributions. Even apart from the external costs and influences in delivering solutions to market (in the case of Habitat building townhomes, this includes increased overhead from training and insurance costs), researchers are generally part of a broader group of experts working towards the final goal. By investing in the development of three separate programs in 2007, Habitat Charlotte addressed the immediate concern around land costs, but also built in flexibility that supported the organization during the housing crash in 2008 because they could leverage a wider range of available land and housing stock. Rather than shying away from talking about outcomes, we need to articulate how the “crooked” line of ethnographic insights actually helps control for external factors by identifying risks, challenges, and opportunities early in the journey so that organizations can plan for change.

The Value of Investing in Ethnography

More traditional measures of ROI are insufficient for measuring the value of ethnographic research because they are limited by the assumptions behind them. Understanding ethnographic impact begs the question of whether, in these traditional models, we are measuring what matters. What if, instead of buying into the mythology of the market, we make explicit the value embedded in ethnographic praxis? In the following section, I will translate these values into more explicit rules that we might use to measure ethnographic impact. In this section, I call out the key foundations of ethnography as a method, an output, and a way of thinking. It is also an enduring conversation, as this anniversary of the EPIC community and twenty years of writing on praxis has illustrated. With its deep history and growing appeal, it’s worth understanding what makes ethnography the proverbial Swiss army knife for making sense out of complexity and finding underlying cultural patterns that shape key behaviors.

One of my favorite definitions of our craft comes from Zora Neale Hurston: “[Ethnographic] research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose. It is a seeking that he[/she/they] who wishes may know the cosmic secrets of the world and they that dwell therein” (1996[1942], 143). Hurston highlights that ethnography is simultaneously systematic and unconstrained by prior assumptions or hypotheses. It is a mindset through which we “decipher the unique cultural logics of human complexity” (Hasbrouck 2018, 5). It is also a deeply ethical practice. Ethnographers do not “seek to manipulate others for ‘scientific’ ends,” but focus instead on the shared humanity between themselves and those whom they study (Atkinson 2015, 5). The richness of ethnographic practice comes from its manifold nature, both technical and fluid, at once embedded and anticipatory.

Our “formalized curiosity” reveals itself in the way we uncover webs of significance and answer the unasked questions. This is because ethnography was built for articulating meaning from ambiguity and identifying the tensions and opportunities inherent in the liminal space that leads to transformation. As our discipline has evolved, these representations are no longer static snapshots of the “other” but dynamic, reflexive, intersectional, and futures-oriented narratives.

Foundation: Webs of Significance

More than a specific method or set of methods, ethnography illuminates “webs of significance” within communities. From mountains to board rooms, ethnographers set out to articulate relationships, meaning, and value from, “a multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit” (Geertz 1973, 10). Ethnography is a wide-angle lens that embraces context and complexity that our stakeholders, understandably, want to filter out when defining their needs. In the field of user experience, for example, context setting for stakeholders is a crucial skill. While the aim of the work that follows our research is to build a digital or physical product, that product is not used in a vacuum. Humans and the products they interact with live in spaces. Unpacking this context for business stakeholders is fundamental to how ethnography delivers value, even before a project starts.

Robin Beers et al. (2011) talk about kicking off a first of its kind ethnographic research effort at Wells Fargo, which more than doubled the time needed for what became routine practice. Beers’ entry experience at Wells Fargo parallels my own in conducting a foundational study of a contact center. As the first researcher in my product space and the only ethnographer at the company at the time, I spent as much time socializing the project proposal and gaining buy-in from director-level leaders on the potential value of the research for a major tech project (replacing legacy software) as I did collecting the data across three sites. Ultimately, what won over stakeholders was the need to understand the workarounds that our employees created to bridge gaps in delivering results for our customers and document when and why those efforts may still not be enough. Such data couldn’t be collected by replaying quality assurance recordings.

Even before entering the field, socializing our approach does two things. First, it highlights the way in which ethnography can help unpack the complexity of the business problem. “We begin to see what has previously been overlooked and perhaps then discover what is truly possible” (Cliver et al. 2010, 231; see also Beers et al. 2011). In my case, the questions I raised in the research plan tapped into the key measure that matters for the business—customer satisfaction—by highlighting the way in which customers are “secondary users” of the software and the pain points inherent within them.[3] It’s worth noting that even when we’re brought in at the tail end of a project, ethnographers can bridge cross-functional gaps with a broader systems view (Sih, et al. 2018).

Design literature often focuses on “systems,” but I posit that the systems we describe are primarily an artifact of our own analysis. Leaning into Geertz’s phrase “knotted into one another,” the part of the “web” that is most significant is the situated relationship.To understand these relationships, Desmond suggests that we study “fields rather than places, boundaries rather than bounded groups, processes rather than processed people, and cultural conflict rather than group culture” (Desmond 2014, 548). The webs within ethnographic praxis are woven between stakeholder groups and the humans being studied, as well as within each of these respective groups. In my case, the relationship with stakeholders was built around identifying those unspoken questions with the customer experience as a particular type of filed nested within a process. In the Habitat example, we took people outside the confines of their home and property line to consider what makes a place a home, which unlocked both tensions and opportunities presented by Habitat Charlotte’s vetting process. Our challenge is to simplify complexity without flattening it, providing enough context to highlight meaningful connections.

Foundation: Time Is about More than Length of Engagement

Classically, we are taught that ethnography involves long stretches of time at a field site, building relationships over months and years. But as far back as the 1960s, participatory methods, action research, and other applied approaches set the stage for kinds of brief but impactful engagements that characterize ethnographic praxis. Our Habitat engagement lasted about 12 weeks. Rather than focus on the amount of time spent on a research engagement, a more productive way to think about time in relation to ethnography is bridging the present to short- and long-term futures. We carry forward or re-unite stakeholders with what is known (Guth 2022) allowing us to go deeper or understand how things have changed (Charland and Hoffman 2017). Time may be more relevant as a factor in our work if we focus instead on things like timing and foresight.

Foundation: Liminality and Transformation

The organizations we work with may or may not be going through a period of conscious change. The problems they present to us, however, might show that they are on the precipice, perhaps wanting to maintain the status quo in the face of external forces or seeking to understand how their target audience is adapting to their own changes. Liminality is not restricted to ritualized movement through life stages or planned transformation. During any period of nascent change, we find that “Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial.” (Turner 1969, 95). The ambiguity and indeterminacy that Turner speaks of open up a multitude of seeds of transformation. Whether the implicit or explicit, these liminal contexts are ones where ethnography can amplify the value of our work by making sense of the inherent ambiguity in periods of change.

Liminal state research inside organizations largely involves making explicit the tacit knowledge of a group. We are stating aloud what is “taken for granted” among the groups we study and report to. Ethnographers working in enterprise teams will sometimes hear “we already know that” from stakeholders. Our challenge is not to complain to our colleagues about our work being ignored, but to tie that tacit knowledge to the field of what is possible. Some researchers, including myself, tap into humor in delivering our insights, while others use workshops or targeted engagements to immerse stakeholders into the lived experiences of “users” they already “know” while exposing bias (Reksodipoetro and McCarter nd; McClard and Dugan 2017). For example, researchers at Intel wanted to embark on strategic research after identifying two dozen separate projects related to the theme of “child’s play.” Their business stakeholders were on the cusp of making decisions about their customers based on cultural biases that were limiting to the business, but the workshop served as a liminal space where leaders could reveal and reflect their biases, opening the way for the necessary foundational research to take place (McClard and Dugan 2017). The timing of this workshop also helped the authors reveal to stakeholders the degree of ambiguity in the space. A key for ethnographers is to both recognize or create openings for liminality and leverage timing to execute our work to deliver insights ahead of key decisions.

Framework for Evaluating Ethnographic Impact

While ethnographic research in the business world can run the gamut from short-term and one-off engagements to longitudinal and iterative studies, each study can be foundational and holds the possibility of creating critical shifts in our collective thinking about a problem. Ethnography is a seed of pure potential. Pure potential also means that not every ethnographic project is going to have a long-term impact. Like a garden, not all the seeds we plant germinate and even those that grow into plants may not thrive. Whether or not an ethnographic project bears fruit, it is worth considering how to measure the harvest.

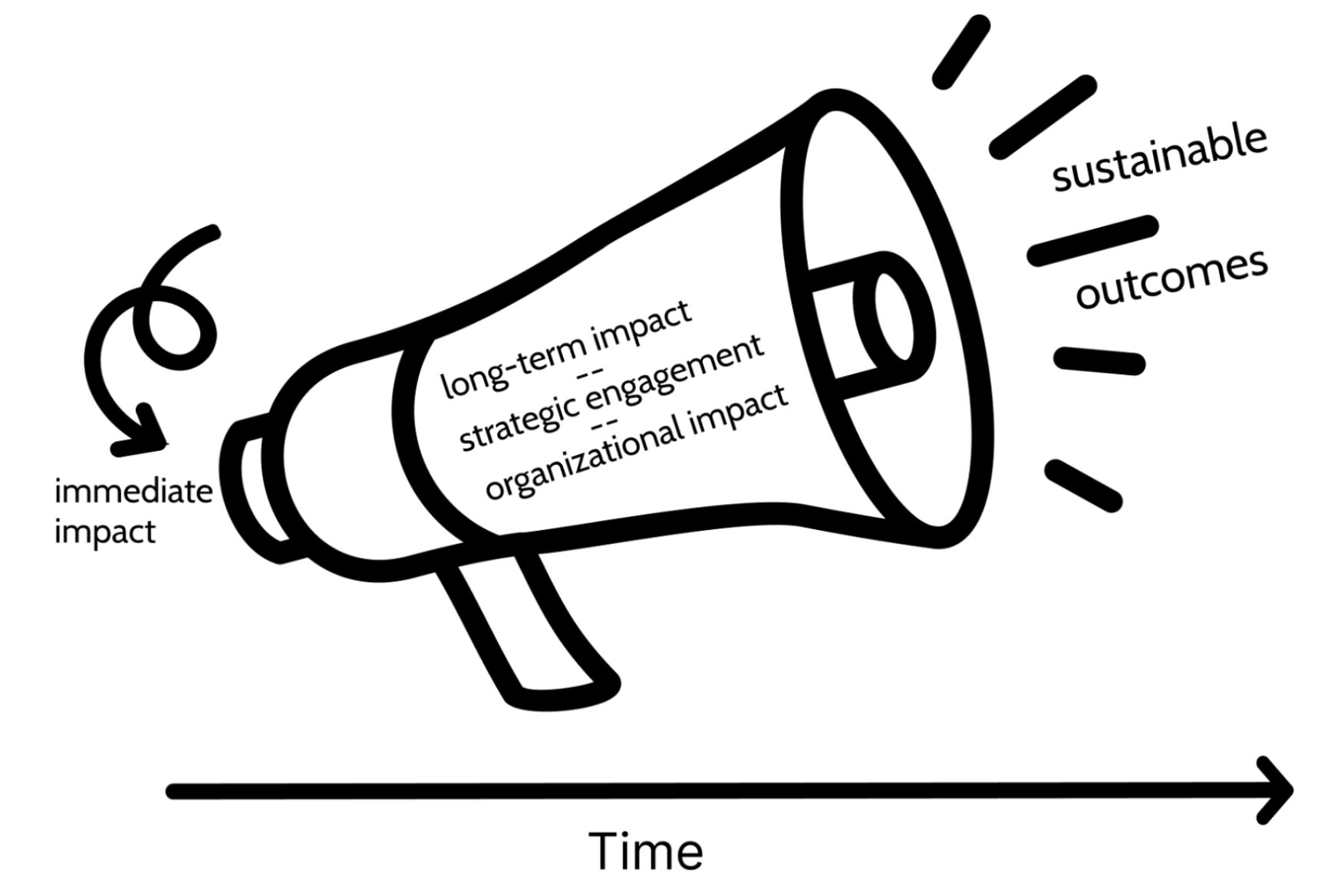

Figure 2. Visual model for understanding how ethnographic impact is amplified over time. Illustration credit: Frank DiTommaso

Determining a long-term impact of ethnography is, by necessity, a retrospective project. Measuring something that hasn’t happened yet is a projection or a forecast but I want to simultaneously encourage us to plan for these elements at the outset of each new ethnographic project even as we reflect on past projects that we might measure now. At the core of this ethnographic impact framework is an immediate impact combined with a matrix of value adds that unfold over a longer time frame (see figure 2). While we might measure the cumulative impact of short- and long-term ROI using traditional measures, ethnographic praxis often amplifies these impacts into something that is beyond cumulative.

A seminal article on “scales of measurement” posits three steps to effective measurement (Stevens 1946). First, we must define the rules; this is, admittedly, the bulk of what this essay will accomplish. Next, the authors ask us to determine the mathematical properties of these scales and apply statistical operations to arrive at a final measure. I hope I will be forgiven for offering a more artistic than statistical treatment of ethnographic impact. If immediate and long-term ROI can be quantified using linear, short-term methods, we can use this as a partial measure. An overall measure of ethnographic impact might be the differential of the status quo subtracted from growth over time. In the Habitat example, this could be a differential of how many more homes were completed as a result of the three new programs implemented compared to the status quo. It could also be the sustainability of outcomes or the virality of an outcome that spreads to other organizations or sectors. In the Habitat example the townhome model would not be “viral” as it was modeled on existing programs at other affiliates, while the Habitat Communities might be. Even in cases where a number can be assigned, we should not forget the context of the intangible value to the humans we study and design for. To break this down, I’ll take each principle of the framework in turn (see Table 1), starting with the tangible elements.

Perhaps most obvious, ethnographic research in the world of business needs to address a compelling, immediate need. Regardless of any longer-term or longer-lasting impacts, we still need to deliver a tangible, measurable outcome for our stakeholders. It may not be easy to correlate outcomes to something like increased sales, but we may tie the delivery of robust, research-driven personas to key benchmarks that our product teams need to hit in identifying a target audience, feature set, and timeline. In one project, I worked with product and UX to flesh out a roadmap for a vaguely defined business “North Star” by providing a framing for pain points with processes and software according to pervasiveness and severity. This was a minor component of the overall project, but was a tangible way to identify “quick wins.” My product owner added in a qualitative difficultly rating for engineering and we used this matrix to define a subset of pain points to solve for within our MVP product launch. By combining the vantage point of the long view with the reality of quarterly planning, we were able to prioritize which quick wins did the most to reduce friction while serving the longer-term organizational goals.

Table 1. Framework Principles for Evaluating Ethnographic Impact

| Framework Principle | Description |

| Immediate impact | A direct outcome that can be measured using “standard” financial or other quantitative measures (eg., increased revenue, conversion rates, clients served, improved CSAT or NPS). |

| Long-term impact | A direct outcome that may be measurable using a “standard” financial or quantitative measure, but is connected to future, rather than short-term, decisions made by the organization. It may be more reasonable to represent this impact with a qualitative narrative over a quantitate measure. |

| Organizational Impact | A direct or indirect outcome related to organizational change. Organizational impacts can be built into the business objectives for the research or they may result from providing direction by answering unasked questions. While a quantitative measure may be possible, this is more likely to be a qualitative measure or narrative. |

| Strategic engagement | Engagement extends beyond transfer of final deliverables, such as developing product strategy or supporting program activation. Engagement can also be episodic and unplanned, such as workshops that identify gaps or reports that reduce “research amnesia.” Strategic engagement is a binary (yes/no) variable. |

| Resiliency – Sustainability | Direct or indirect qualitative outcomes that represent the durability, longevity, or flexibility of both immediate and longer-term impacts over a broader time-frame. |

Direct outcomes can happen across multiple time horizons. Even when an organization asks specifically for future-oriented research, our research insights are rarely aimed exclusively at a 3–5 year horizon. For such future oriented projects, we increase our impact by taking the opportunity to suggest quick wins or immediate first steps, like the mapping of employee pain points against severity and pervasiveness, described above. Likewise, projects that ostensibly focus on immediate needs may lend themselves to broader inquiries, such as McClard and Dugan’s work on “child’s play” (2017), or to multiple solutions across a longer time-horizon, as in the Habitat Charlotte reflection I began this paper with, where the immediate quick win was to leverage existing crews to start up the Critical Home Repair program, the anticipated short-term impact was townhomes, and the long-term impact was Habitat communities. In addition to the direct outcomes whose value can be approximated through more traditional ROI calculations, ethnography brings tangible (if not strictly measurable) and intangible values that can be talked about in comparative terms, such as the value experience of Habitat Charlotte homeowners who were afforded a wider array of choices to fit their desired lifestyle. Measures of impact that are the most meaningful can always be defined with precision, even if they cannot be quantified.

Organization change, like the opportunities to offer long-term recommendations, is not always part of the “ask.” My corporate ethnography project with the pervasive and severe pain points was framed as a “lift and shift” of a primary tool, with opportunities for “value add.” In the beginning (and perhaps even now), our business partners on the project would not have said they were “betwixt and between”—they had a North Star vision. What marked that project as “liminal” was my manager seeing value in using ethnography as a route to identify both shorter and longer-term needs and site directors buying into the vision I set forth. The key to this principle is that ethnographers can leverage the liminality they’ve identified in an organization to drive new ways of thinking. Organizational shifts might be as small as hearing a term used in your research report be adopted by members of the C-suite. With the opening Habitat example, the organization was clearly at an inflection point and by digging into the meaning of “home” we were able to tie back ethnographic insights to the organizational mission, making insights around alleviating the pressure homeowners felt to “lift up” their neighbors less difficult for stakeholders to hear. Ethnographers must learn about what is at stake for the client beyond the business (financial) objectives.

Another principle of how ethnography provides a long-term impact is strategic engagement. If one were to think about these principles and their direct and indirect measures as variables in a multi-variate equation, strategic engagement would be a binary variable—we find a way to do it or we miss out on an opportunity to increase our impact. Working in-house certainly opens more opportunities for extended engagement, even if engagement is not always easy (see: Beers et al. 2011; Guth 2022). The novel approach to pain points I implemented brought up multiple opportunities to work collaboratively on product roadmaps. Strategic engagement certainly doesn’t require standing in through the ideation or execution of a new product or service, but is more about shepherding insights through the process and ensuring the voice of the beneficiary or consumer isn’t drowned out by shareholders, efficiencies, or competing priorities. As a consultant, you may build in workshops or initial concepts as post-readout deliverables. In the case of Habitat, I remained active as part of an “advisory” group as the core team moved forward with approving building plans and volunteer safety requirements for multi-family units. Strategic engagement is a process of building communitas at the “edges” and “interstices” (Turner 1969, 128). It is about finding strategic allies and identifying ways to extend the conversation past the readout.

The final principle is resiliency and sustainability of outcomes. If we manage to identify key opportunities for positive (financial, social, organizational) change that address both short- and long-term needs, the impact is not simply outcome + outcome = impact. Change is the constant. Incremental improvements don’t necessarily keep us moving towards a singular goal. If a research engagement can help to set a strategic vision that is achieved over years, including additional research and planning, the initial research is not invalid. Rather, the direction set by foundational, strategic research lays out a path to a sustainable business model. Again, Habitat Charlotte didn’t choose a single path forward and they didn’t prioritize their hypothesized model above the other possibilities. Rather, they followed multiple paths that allowed the organization to remain responsive to dramatic market forces, like the 2008 housing crisis. The number of homes they built in 2007, 2008, even in 2012 is far less important than the sustainable, affordable housing model that they have built by honing in on community in both the literal and the figurative sense. If you ask me about the impact of my research in 2006, I would tell you that by shifting the mental framework of how they build, Habitat Charlotte created a flexible housing model that includes infill housing, renovated homes, townhomes, and entire communities, allowing them to nearly triple the number of families served annually even as Charlotte-area housing costs skyrocket. The quantitative impact is more homes and more families served. The ethnographic impact is operational flexibility, strengthened feelings of community, and increased levels of service.

Conclusion

Ethnographers often shy away from assigning value to our work, but as we move into a new decade of ethnographic praxis, it is time to embrace our value in concrete terms. Being concrete does not, however, mean we have to fall into the trap of over-indexing on short-term financial metrics. With ethnography, it is not an either-or choice between short-term gains and long-term value. Our craft is one of the few that is equipped to explore and define ambiguity, liminality, and multiple time frames, so we can use this skill built through our practice to define the immediate, long-term, and organizational impact measures that situate our work solidly in both tangible outcomes for our clients and the populations they serve. As time passes, it’s useful to revisit these measures to understand how our work has prompted deeper organizational changes or created resilient solutions because of the ways in which ethnography illuminates potential challenges and opportunities. Most importantly, for the generation that will be the new torchbearers of our craft, thinking through impact at the start of a project, whether or not that vision is realized, can help frame the work for stakeholders and support the continued evolution of our field.

About the Author

Katherine Metzo, Ph.D. is currently a Lead UX Researcher at Lowe’s Home Improvement. She has worked in academia, grassroots policy, customer insights, and design research. Finding mastery in the craft of ethnography and illuminating fundamental aspects of the human condition are the threads that weave these chapters together. katherinemetzo@gmail.com

Notes

The author is grateful to Matt Lane for support at multiple points during the writing process. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of Lowe’s Home Improvement.

[1] 1983 is the year Habitat for Humanity affiliate was formed in Charlotte.

[2] Visit Sauro 2015 for key quantitative UX metrics. See Hazen, et al. 2020 for an example of how to apply quant measures to design research.

[3] See Youngblood and Chesluk 2021 for a framework for studying indirect and possibly involuntary product experiences based on the physical and social environments we inhabit.

References Cited

Atkinson, Paul. 2015. For Ethnography. Los Angeles: Sage.

Beers, Robin, Tommy Stinson, and Jan Yeager. 2011. “Ethnography as a Catalyst for Organizational Change: Creating a Multichannel Customer Experience.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2011), pp. 61–76. https://www.epicpeople.org/ethnography-as-a-catalyst-for-organizational-change-creating-a-multichannel-customer-experience/

Charland, Carole and Karen Hofman. 2017. “Bringing Attention to Problem Solving and Meaningfulness at Work: How Ethnography Can Help Answer Difficult Business Questions.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2017), pp. 320–335. https://www.epicpeople.org/problem-solving-meaningfulness-at-work/

Cliver, Melissa, Catherine Howard, Rudy Yuly. 2010. “Navigating Value and Vulnerability with Multiple Stakeholders: Systems Thinking, Design Action and the Ways of Ethnography.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2010), pp. 227–236. https://www.epicpeople.org/navigating-value-and-vulnerability-with-multiple-stakeholders-systems-thinking-design-action-and-the-ways-of-ethnography/

Cooper, Alan. 1999. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why High-Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Indianapolis: SAMS.

Desmond, Matthew. 2014. “Relational Ethnography.” Theory and Society 43(5):547–579.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Guth, Kristen L. 2022. “Creating Resilient Research Findings: Using Ethnographic Methods to Combat Research Amnesia.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2022), pp 294–316, https://www.epicpeople.org/creating-resiliency-of-research-findings/

Hasbrouck, Jay. 2018. Ethnographic Thinking: From Method to Mindset. New York: Routledge.

Hazen, Rebecca J, Genny Mangum, and Tom Souhlas. 2020. “Scaling Experience Measurement: Capturing and Quantifying User Experiences across the Real Estate Journey.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2020), pp 117–126, https://www.epicpeople.org/scaling-experience-measurement-real-estate-journey/

Hurston, Zora Neal. 1996 (1942). Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography. Harper Perennial.

Kucheriavy, Andrew. 2017. “How UX is Transforming Business (Whether You Want It to Or Not).” Forbes. January 23, 2017. Accessed 8/5/2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2017/01/23/how-ux-is-transforming-business-whether-you-want-it-to-or-not/

Maxwell, Chad. 2021. “Demonstrating the Impact of Ethnography: Chad Maxwell on ROI and New Kinds of Ethnographic Value.” EPIC Perspectives. Accessed 8/5/2024. https://www.epicpeople.org/demonstrating-the-impact-of-ethnography/

McClard, Anne Page and Therese Dugan. 2017. “It’s Not Childs’ Play: Changing Corporate Narratives Through Ethnography.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2017), pp 336–348. https://www.epicpeople.org/childs-play-changing-corporate-narratives-ethnography/

Metzo, Katherine. 2008 “Homeownership and Community Transformation: Habitat for Humanity in Charlotte, NC.” Anthropology News, 49(9): 11,14

Reksodipoetro, Adri and Alexandra McCarter. nd. “How Ethnographic Exhibits Can Shift Business Paradigms.” EPIC Perspectives. Accessed 8/3/2024. https://www.epicpeople.org/how-ethnographic-exhibits-can-shift-business-paradigms/

Sauro, Jeff. 2015. “10 Metrics to Track the ROI of UX efforts.” Measuring U blog (September 1, 2015) Accessed 8/5/2024. https://measuringu.com/ux-roi/

Sih, Brady, Hillary Carey, and Michael C. Lin. 2018. “Getting from Vision to Reality: How Ethnography and Prototyping Can Solve Late-Stage Design Challenges.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (2018), pp. 457–465, https://www.epicpeople.org/ethnography-prototyping-late-stage-design/

Stevens, S. S. 1946. On the Theory of Scales of Measurement. Science. 103(2684): 677–680.

Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Youngblood, Mike and Benjamin Chesluk. 2021. Rethinking Users: The Design Guide to User Ecosystem Thinking. Amsterdam: Bis Publishers.