With insights from original, multinational research and analysis of key social science studies, this paper deepens our understanding of how and why social media is changing. We explore the evolution of social media and “public broadcasting” over the past two decades, arguing that teen participants have shifted away from the original social media paradigm and towards more private and ephemeral forms of sharing. Building on existing theories of “context collapse”, we examining how traditional boundaries of audience, time, and meaning blur on social platforms. Rich ethnographic research shows how teen participants have adapted to multidimensional context collapse through multilayered, generative strategies that challenge the perceived passivity of their “empty profiles”, allowing them to reclaim social media as a place that reflects their generation’s values.

Introduction

When EPIC was founded in 2005, the foundations of social media were still in their infancy: blogging platforms like WordPress dominated, and “The Facebook” was only just gaining traction in the dorms of Harvard. In 2004, the authors of this paper were still in their teens, eavesdropping on their older siblings’ cordless telephone conversations about the latest school gossip (cf. March and Fleuriot 2005) or starting their own MySpace accounts (cf. Faulkner and Mellican 2007).

When the first users of social networks began to explore platforms like Myspace and Facebook, they encountered platforms that rapidly scaled up the number of people with whom they could connect and share about themselves. One-to-many communication—once the domain of traditional media broadcasting—was now something anyone could do. Anthropologists such as Daniel Miller in his Why We Post series studied this “public broadcasting” affordance of social media (2016). The original social media paradigm was a space where people could post about their lives to audiences known and unknown.

Based on a multi-country ethnographic study conducted in early 2023 with teens, this paper argues that there has been a significant shift in the way teen participants use social media today in comparison to the original paradigm. In our study, a large proportion of participants no longer posted to social media feeds publicly, or at all—their profiles on various platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter were empty. If Miller were posing his question of Why We Post today, perhaps it would be Why Don’t We?

To answer this question, we situate today’s social media use within a historical context. We examine the evolution of social media over the past two decades, arguing that its technological affordances and mainstream adoption have facilitated ever-increasing forms of “public broadcasting” and subsequent “context collapse” on these platforms.

In its simplest definition, context collapse refers to the flattening of audiences into a single context (Marwick and boyd 2010) in digital spaces. It has the effect of destabilizing an individual’s self-presentation, collapsing identities and behaviors that are normally kept separated for distinct audiences. Context collapse is inherent to “mediated technologies” (boyd 2008) and profoundly shapes the way that people interact online (Abidin 2021; boyd 2014; Brandtzaeg and Lüders 2018; Hogan 2010; Wesch 2009), evidenced particularly strongly in our study with teen participants. Although scholars such as boyd identified the phenomenon of context collapse as early as 2008, its effects seem to have become more pronounced with the evolution of social media technology and the affordances we have today.

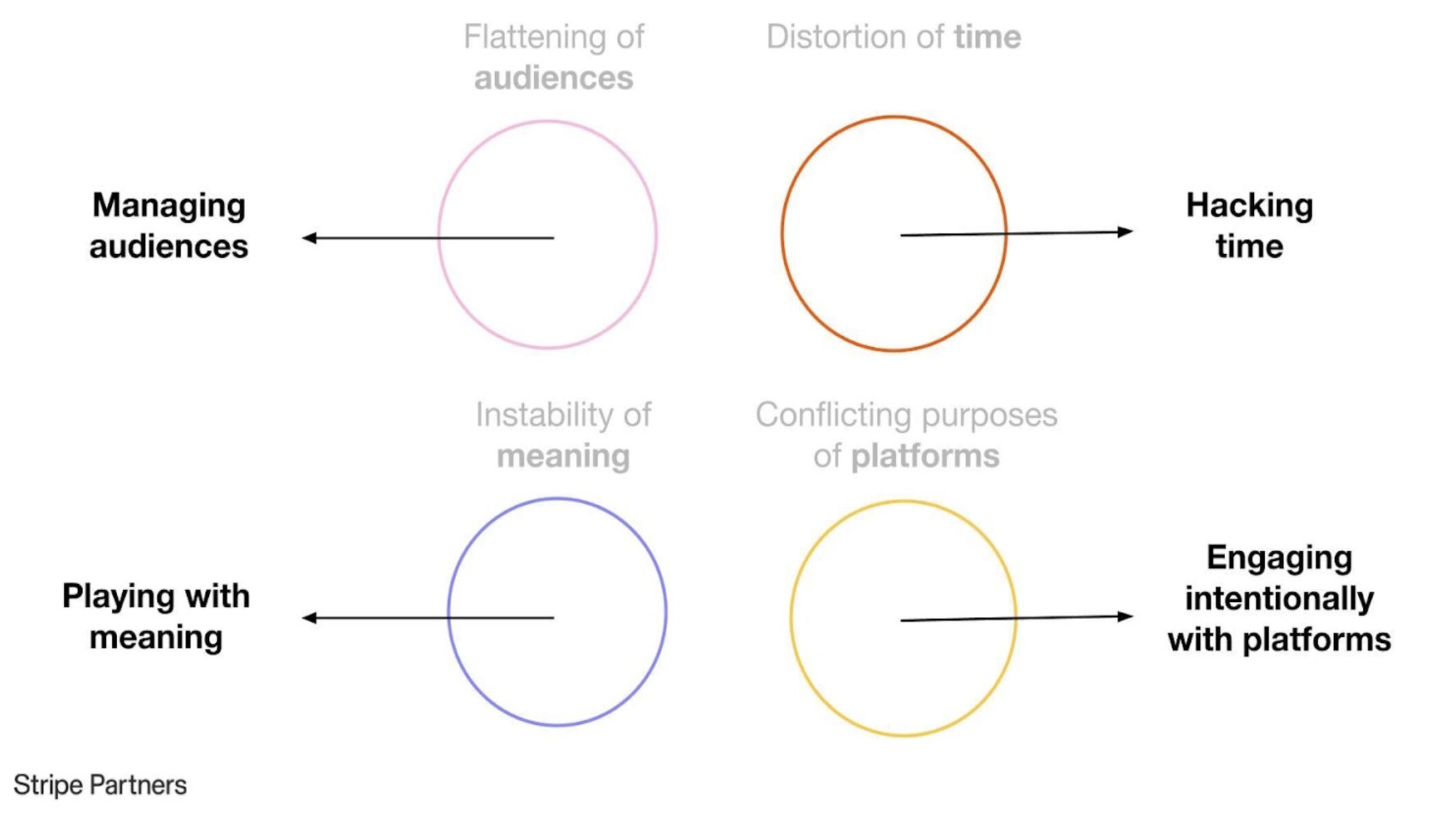

Based on our original ethnographic research, we propose an expanded framework of multidimensional context collapse encompassing:

- Flattening of audiences

- Distortion of time

- Instability of meaning

- Conflicting purposes of platforms

Furthermore, our analysis reveals the generative, nuanced strategies that teen participants employ in response to context collapse, allowing them to reclaim social media as a place that reflects their generation’s values. Teens in our study were adept at:

- Managing audiences

- Hacking time

- Playing with meaning

- Engaging intentionally with platforms

Our core insights were developed during an initial study of teen participants’ social media use in Spain, the UK, and South Korea across a variety of platforms including YouTube, Twitter, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Pinterest, TikTok, Discord, Facebook, BeReal, Reddit, Instagram, LINE, Kakao Talk, and Cyworld. However, subsequent studies with teen participants in six additional countries (Japan, Brazil, France, Italy, Australia, and the US) demonstrate that these insights hold across a variety of locales. This suggests a broader shift in the way younger generations use social media.

Although numerous scholars over the years have elucidated the ways in which teens have crafted adaptive strategies for engaging with social technology (Abidin 2020; boyd and Marwick 2011; Gopffarth et al. 2022; Ito et al. 2010; Rangaswamy and Yamsani 2011), in this paper, we highlight specific behaviors from teen participants that demonstrate how they operate, by default, with self-awareness of multidimensional context collapse. In particular, we discuss the now commonplace practice of “not posting”. When teen participants spoke about “posting”, they equated it to the public, permanent sharing of content about themselves to social media feeds—content that remains on their profile. The majority of study participants tended to avoid this form of self-disclosure. Instead, we observed that most sharing behavior is now private and ephemeral by default, and public and permanent only through effort (with deliberate strategies).

We propose that the patterns observed in our research of participants’ empty profile grids across a variety of apps do not reflect an abstinence from social media for those teens, but rather an intentional engagement with it that is a generative response to context collapse. Their strategies and alternative forms of “posting” underscore the resilience and intentionality of young people in shaping their digital experiences (Gopffarth et al. 2022), challenging notions of passivity and vulnerability. To answer the question Why Don’t We Post?, we must look beyond the behavior of public posting to the multifaceted approach that they use to express themselves and connect with others online.

To conclude our paper, we will discuss possible new directions for understanding teen experiences with social technology, which help us to view the relationship between teens and technology not as deterministic, but as negotiated.

The Evolution of Social Media

A review of two decades of social media (with a focus on globally popular platforms) demonstrates how its affordances have given rise to increasing degrees of “public broadcasting”, that is, the dissemination of content or other digital “records” to large audiences online.

Social Networking’s Early Years: New and Extended Forms of Social Connectivity (2004–2009)

In the years leading up to the launch of “The Facebook” at Harvard University in 2004, teenagers were already making use of preexisting technologies that enabled digital connection with friends and peers. In particular, cordless phones and cellphones introduced more mobile and “on demand” formats of communication and socialization. March and Fleuriot (2005) illuminated how these phones allowed teenagers in the US and UK to carve out spaces to connect with friends out of earshot of family members. Similarly, Asokan (2008) highlighted how teenagers in India developed subtle ways of using technology like cellphones to navigate the blurring of personal and public spaces, creating “their own space in the heart of social activity at home”.

Extended forms of online social activity began to take off with platforms like WordPress and YouTube. Blogging and vlogging became increasingly popular ways of “getting noticed, showing-off, [and] being overheard” by global audiences (Faulkner and Melican 2007). These technologies enabled a diverse array of individuals and communities to express themselves—creatively, entrepreneurially, or even in the pursuit of social change.

At the same time, the practice of blogging began to trigger reflection and engagement with questions of online identity management. Now, content creators needed to consider how to present themselves to a variety of audiences, both known and imagined (boyd 2014; Faulkner and Melican 2007; Marwick and boyd 2010), and how to convey a message that would experience narrative changes as it got passed along to more friends.

Amongst the early social networking sites—or “networked publics” as danah boyd referred to them (2008)—MySpace was a site that became central to peer sociality. In the words of one of boyd’s participants, “If you’re not on MySpace, you don’t exist.” Alongside MySpace, Facebook was gaining traction: it went from 12 million users in December 2006 to 100 million in less than two years (Brügger 2015). Social networking was becoming a global phenomenon, evidenced by a number of similar sites launched in other countries, such as Cyworld in South Korea in 2005 (boyd 2008; Horst and Miller 2012). However, none had attained the reach of MySpace and Facebook, where teenagers relished their newfound ability to create elaborate online profiles, glean more information about their friends, and display different dimensions of themselves (boyd 2008; Ito et al. 2010).

While teenagers primarily used these sites to connect with close friends and people they already knew, these technologies allowed “many teens [to] move beyond small-scale intimate friend groups to build ‘always-on’ networked publics inhabited by their peers” (Ito et al. 2010). Social networking sites introduced public facing aspects to social connection and self-presentation that had not existed previously. Implicit social dynamics were made explicit. Features like publicly visible friend lists and the ability to comment on profiles allowed others to “overhear” a conversation to which they may not have been privy in the physical realm. When Facebook introduced the News Feed feature in September 2006, this process of seeing actions taken by friends on the site became core to the experience (Ito et al. 2010).

From Social Networking to Social Media: Mobile, Ubiquitous Access to Visual Content Creation and Distribution (2010–2014)

By the early 2010s, smartphones and mobile connectivity had become mainstream (boyd 2014; Madden et al. 2013), allowing constant access to the Internet (Campbell 2013; Ling 2012). As Rangaswamy and Yamsani (2011) highlight in their exploration of teen online practices in India, many teens’ first experience of the internet was on a mobile phone.

The “mobile internet”, which connected users synchronously, asynchronously, and while in transit (Campbell 2013), played a crucial role in facilitating the ubiquitous presence and embedded practices of online social connection in the daily lives of teens (boyd 2014; Horst and Miller 2012). Sites like Facebook and Twitter became central to their coming of age experiences. No longer subcultural, they were now normative in Western contexts (boyd 2014; Horst and Miller 2012).

It was at this point, in the 2010s, that a shift in terminology was needed, to signal a transition from social networking to social media. Most social networking sites had evolved to popularize the creation and sharing of content, and the launch of platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, Tumblr, and Vine prompted a move towards visual and image-based content (boyd 2014; Highfield and Leaver 2016; Miller et al. 2016).

The default design of these social media platforms was their support of sharing content with broad audiences, facilitating new methods of distribution “by explicitly or implicitly encouraging the sharing of links, providing reblogging or favoriting tools that [reposted] images or texts, or by making it easy to copy and paste content from one place to another” (boyd 2014). boyd notes that teens embraced these practices and were enthused about uploading photos, tagging people, and commenting online because it provided a means to extend the enjoyment of shared experiences with friends (boyd 2014). Smartphones facilitated constant content creation, while social media sites facilitated its broadcasting (Highfield and Leaver 2016; Marwick 2015).

In this period of social media growth, visual content introduced a new way to communicate, fashion, and perform identities (Highfield and Leaver 2016). However, questions of online identity expression were about to become even more complicated with social media’s next innovation: the algorithmic feed.

Algorithmic Social Media: Personalized Feeds and the Rise of Influencer Culture (2015–2019)

The nature of information sharing, self-presentation, content consumption, and online social connection changed dramatically with the more widespread shift from chronological to algorithmic feeds in the mid 2010s on major platforms such as Twitter and Instagram (Schulz 2023). Now content that appeared to users was personalized by the algorithm, which excluded some pieces of it while highlighting others (Gillepsie 2014). Algorithms upranked content that was aligned with individuals’ interests, and posts that had mass appeal across platforms were referred to as “trending” or popular. Upranking created the possibility that any trending piece of content could potentially be launched into others’ feeds, beyond the anticipated audiences.

Algorithms “manage our interactions on social networking sites” (Gillepsie 2014) when they tailor what we see and therefore interact with. However, the underlying mechanism is a two-way street—a feedback loop between people’s behaviors on the app (clicks or taps, likes, views, comments, etc.) and the algorithms’ subsequent recommendations (Gillespie 2014; Klug et al. 2023). In other words, “What we see is no longer what we get. What we get is what we did and that is what we see” (Bucher 2018).

However, algorithms cause a second, more significant effect: not only do they allow users to shape what they themselves see, but also what others see. People can engage in practices that “amplify their efforts” and ensure their content gets picked up by an algorithm and distributed to larger audiences (Abidin 2020; Gillespie 2014), for example, through the strategic use of hashtags. Gillepsie (2014) highlights how teens on Facebook would “tag their status updates with unrelated brand names, in the hopes that Facebook [would] privilege those updates in their friends’ feeds.” Thus, people are “not just joining a conversation…[they] are redesigning [their] expression so as to be better recognized and distributed by…search [algorithms].” What we come to know about others online is both socially, and arguably, platform constructed.

The affordances of algorithmic social media set the stage for, and were inextricably linked to, the rise of influencers on social media in the mid 2010s, or what many scholars term “micro-celebrities” (Abidin 2015, 2020; Marwick 2015; Senft 2013). Influencers’ practices were aimed at maximum visibility and exposure, in order to attract and compete for mass audiences historically limited to broadcast media (Abidin 2015, 2020). While influencers’ direct, commercial strategy included integrating “advertorials” into social media posts to promote sponsored products, the more tacit social strategy underlying their practices was that of crafting an aspirational online persona and identity for their viewers (Abidin 2016).

Although YouTube was an important platform for influencer vlogging content, much of the curated, photo-based persona content was generated on Instagram during this period. Instagram micro-celebrities had amassed vast audiences of followers, and their highly popular content was being pushed to the feeds of hundreds of thousands of people everyday. But popular is not the same thing as viral—and with the rise of TikTok, public broadcasting was about to take on a whole new meaning.

Viral Social Media: Remixing Drives New Forms of Visibility and Influencer Practice (2020–Present)

TikTok was launched in 2016, grew significantly from 2018, and then experienced a massive surge in teen usership in 2020, coinciding with increased internet use during the pandemic (Abidin 2020; Klug et al. 2023; Wei 2021). Its algorithm ushered in what Abidin (2020) referred to as a “new frontier of social media” in which TikTokers were “actively and very quickly adapting [to] the latest trends and viral practices…to aim for the For You Page, or the ‘golden ticket’ that would allow one to gain an immense number of followers overnight”.

On TikTok, the nature of influencer culture shifted. Whereas Instagram was largely predicated on the careful curation of a “singular coherent persona or style” by “‘staging’…an ‘Instagrammable’ lifestyle that was aspirational and pristine”, TikTok influencers crafted “relatable” performances that felt entertaining and accessible to wide audiences, through a kind of “calibrated amateurism”. Wei (2021) sums this up by saying “Whereas Instagram is performative, TikTok is performative and self-aware.”

In tracing the evolution of social media over the past two decades, it becomes clear that the scale of public broadcasting has increased over time, owing to the progression in the technical capabilities of the mobile internet and these platforms, as well as their mainstream adoption and global success. This, in turn, has created the conditions for increased context collapse. Social media platforms bring together multiple, diverse audiences into one space and make it possible for information to be accessed across space and time at an accelerated rate. When users engage with today’s social media platforms, they find themselves needing to manage a greater number of collapsed social contexts online.

We now turn to the present era through the lens of our ethnographic research. After introducing our study’s methodology, we propose a framework that reflects teen participants’ experience of multidimensional context collapse, and the generative strategies that they employ to navigate it.

An Ethnographic Study of The Emerging Paradigm of Social Media for Today’s Generation of Teen Participants

Methodology

In March 2023, we carried out a multi-method ethnographic study of teen participants’ social media use across a variety of platforms including YouTube, Twitter, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Pinterest, TikTok, Discord, Facebook, BeReal, Reddit, Instagram, LINE, Kakao Talk, and Cyworld. The study was a collaboration between Stripe Partners and Meta. We conducted research with 127 teen participants (ages 13–17) in South Korea, Spain, and the UK,[1] to bring a global perspective to emerging teen social media practices. Our research methodology comprised a diary study, interviews with friendship groups, as well as participant observation in public spaces popular with teens.

The diary study generated a wealth of digital artifacts, painting a picture of the daily online practices of study participants—blank social media profiles, playful avatars, intentionally vague usernames, blurry photos, insider memes and various group chats. This data was analyzed thematically, allowing us to explore teen participants’ aesthetics, cultural codes, and the values these represented.

In our interviews with friendship groups, we explored their social media values through several activities such as app ecosystem mapping, explorations of online norms and etiquette (in the words of a participant: “cringey and “not cringey” behaviors), and ideation exercises that prompted them to design the “best” or “worst” social media app. We analyzed this data using a grounded theory approach, coding themes from both interview responses and the artifacts generated in the activities.

For our immersions into public spaces, young adult participants guided us through locations popular with youth such as arcades, shopping malls, basketball courts, and Korean cafes. Observing study participants’ socialization within these spaces and taking part in a number of their favorite activities allowed us to gain a more holistic perspective of the connection between their online and offline practices, as well as embed ourselves more fully into their cultural contexts. The data from these immersions was incorporated into our analysis of the interviews.

A Framework for Multidimensional Context Collapse

Rooted in our ethnographic work with teen participants, we propose a context collapse framework that consists of four key dimensions:

- Flattening of audiences: in contrast to offline experiences, online audiences are significantly more vast and mixed, and social circles are often bundled together.

- Distortion of time: time no longer possesses a linear or sequential nature on social media—the past does not stay in the past, the present doesn’t stay in the present.

- Instability of meaning: content can circulate unpredictably, with the poster having varying levels of awareness of how this is taking place. The meaning of the content can be continually remixed and reinterpreted.

- Conflicting purposes of platforms: social media platforms bring together multiple purposes for their use, with one example cited by teen participants being the personal vs commercial uses of platforms.

All four dimensions play a significant role in study participants’ experiences of context collapse on social media today. At the same time, the constituent elements are highly interconnected, creating a complex set of considerations for engaging online.

For example, when teen participants decide to post a photo of themselves to a social media feed, they are aware that multiple audiences may view it, including friends but also family members, teachers, and potential employers. For many participants, this is reason enough to stop posting entirely: Isabella[2] from Spain told us, “If you publish something, it’s totally open, anyone can see it. That’s why I don’t want to publish stuff.”

Added to this, their photo may still be visible to these audiences at a future moment in time, representing them in a way that is no longer consistent with certain characteristics or interests. In South Korea, many teen participants spoke about the desire to obscure their face. In one group interview, participants discussed the lengths they would go to, either covering their face in photos or only posing in group selfies. Ye Joon explained that pictures of their face might circle back in an undesirable way: “People might really look at your face. They might capture it. If it’s captured it can be used in the future against you. You don’t want people to think you’re a child.”

Furthermore, study participants are wary that their content might be reshared into other online contexts, and even edited by others in such a way that it no longer reflects the original message intended by the photo.

Given this complexity, our four dimensional framework is not an attempt to reduce context collapse to a strict formula or show it as a static phenomenon. Rather, our aim will be to illustrate each dimension’s nuances and the roles they play together in creating teen participants’ experiences of context collapse online.

Our ethnographic study revealed that in response to each dimension of context collapse, participants develop strategies to mitigate, or even take advantage of its effects.

Study participants:

- Manage audiences by using different apps, creating multiple accounts, and meticulously (re)adjusting the settings of follower lists and individual pieces of content to correspond to nuanced social circles.

- Hack time by defaulting to ephemeral forms of interaction, curating their published memories, carving out spaces for private memory banks, and developing content in the present with a view towards the future.

- Play with meaning by decentering themselves in posts, subverting platform norms, communicating indirectly, and encoding messages online.

- Engage intentionally with platforms by humanizing and personifying app algorithms to help them rationalize decisions and retain a sense of agency.

In all of these strategies, an important feature of many teen participants’ behavior is the tendency to avoid public posting to social media feeds, which represents a distancing from the original paradigm of social media. Study participants’ diary submissions featured a plethora of screenshots of blank profiles, and during interviews, the phrase “I don’t post much” came up constantly. However, this practice cannot be viewed as a wholesale rejection of social media. On the contrary, teen participants find many other ways of engaging meaningfully and intentionally with friends, peers, and their wider communities on these platforms. In other words, rather than passively accepting context collapse, study participants actively adapt their behaviors to reclaim social media as a place of their own (boyd 2014).

Below we explore the dimensions of context collapse in detail. For each dimension, we will highlight previous scholarly work that has contributed to our understanding, the perspectives and experiences of teens in our study, and the generative strategies that they use in response.

Context Collapse Dimension #1: Flattening of Audiences

Context collapse has often been closely associated with the collapse of audiences online, and multiple scholars have examined the subsequent effect on self-presentation and expression in digital spaces (boyd 2008; Hogan 2010; Marwick and boyd 2010; Wesch 2009). boyd (2008) described context collapse as the challenge of delineating potential different audiences online—the boundaries that are normally present in offline experiences do not apply in online spaces, resulting in a bundling of audiences. For example, teen participants described how those in positions of authority, such as parents, teachers, coaches, or even potential employers were all possible witnesses to their digital interactions.

Much of the scholarly understanding around the effects of audience collapse is rooted in Goffman’s framework (1959) of social situations and performances. In the absence of clear boundaries online between front and back stages, and between different audiences, social contexts become collapsed, disrupting the process of impression management. The design of many social media features for public broadcasting has a tendency to bring what would otherwise be backstage behaviors (such as more “authentic” or personal expression) onto the front stage, turning them into performances which require users to reckon with how to present to a mix of audiences.

Michael Wesch’s work on YouTube vloggers (2009) described the phenomenon of audience collapse in this way: “The problem is not lack of context. It is context collapse: an infinite number of contexts collapsing upon one another into that single moment of recording.” Applying Goffman’s theory of stages and performances, he described how this phenomenon created a “crisis of self-presentation” for vloggers. They had to imagine an infinite number of potential audiences and “address anybody, everybody, and maybe even nobody all at once.”

We found that these observations regarding the flattening of audiences held true for teen participants in all markets, who feel it is difficult to delineate different social circles online. In offline contexts, teen participants have intricate social ecosystems with varying degrees of relational closeness between individuals and groups. However, when it comes to social media, study participants are highly aware that apps do not have structures that reflect these nuanced degrees of social intimacy.

Online, the boundaries that exist between social groups in the physical world have no clear digital equivalent. Any digital interaction, be it sharing content, commenting, or even liking a post can be broadcast to an audience where many forms of social diversity are collapsed into one. Some platforms have settings that allow for sharing with different audiences, such as “Close Friends” on Instagram or “Best Friends” on Snapchat, but these introduce binary categorizations that force, and make public, social distinctions that are not aligned with or expressed explicitly in offline settings (as Ito et al. 2010 have noted). When study participants were asked to design their dream social media app, one group of South Korean participants went well beyond the binary Close Friends feature, designing a social intimacy scale from 1-100 that would intelligently sort what content would be shared with who, creating nuanced layers of access.

Teen participants are conscious of the mix of age groups in online audiences, or those who “aren’t the same age as them”. This was especially highlighted amongst South Korean participants, where strong age hierarchies and respect for those who are older than oneself (not just adults, but older teens) are an embedded aspect of their culture. In South Korea, it is most common to socialize within one’s year group—in fact, one of our research partners informed us that the Korean word for “friend” (친구 (chingu)) is generally only used for someone of the same age. This attention to age means that teen participants avoid being on apps where audiences are thought to be “too old” or “too young”, and consider it appropriate to use certain apps at different stages of adolescence.

Furthermore, study participants are confronted with the fact that their parents are sometimes on the same apps as them, including in the years before they themselves arrive on the app. One participant lamented over what he described as “moms posting pictures of their kids on social media, trying to expose them, like ‘First day of school, fam!’”.

In previous work on context collapse, boyd (2008) pointed out that in many cases, online audiences are not only bundled together, but also unknown or invisible. Thus, she often referred to how her teen participants would “imagine” their audiences on social media (2014). However, we observed that participants in our study take this one step further—they often assume, by default, that their content will be seen by any member of these vast audiences, and this mindset shapes their behavior and forms of engagement on many different apps—in particular, their tendency to avoid posting to social media feeds.

The Flattening of Audiences Online Leads Teen Participants to Manage Audiences

In response to audience collapse, teen participants are constantly managing audiences using a variety of apps, tools, and settings.

Study participants find ways to create multiple layers of social intimacy online, crafting separate spaces for their different social groupings and for their own personal use. For example, study participants choose to use different apps to keep audiences distinct and to tailor their online self-presentations accordingly. For most participants, Snapchat is largely used to interact with friendship circles, while Instagram is used to add broader audiences to their network such as acquaintances or to advertise entrepreneurial pursuits. On the other hand, TikTok and Twitter are often used to “be the audience” rather than “be the performer”: these are platforms where they can be entertained or receive in-real-time updates about interests or favorite creators.

Within a single app, one “tried and true” way of carving out audience boundaries is through the creation of multiple accounts (Ito et al. 2010). On apps such as Instagram, having two accounts is commonplace, one for presenting a more “curated” set of photos or videos, usually to somewhat larger audiences, and one that is a more “personal” account, often described by teen participants as their “silly” or “spam” account that they use to send casual updates and engage with closer friends.

However, two accounts is just the starting point for many study participants. One of our participants, Ha-Eun, related that she has “seven different accounts, which include three for different friend groups, one for my interest in drawing and also one just for studying”. Her approach is emblematic of how participants across the study use separate accounts for different purposes and audiences. In a similar way, Julia from Spain informed us of the typical process: “You start off with a main account, where you follow loads of people, and then you make a more private one.” Her friend Alberto agreed, commenting that “You start caring less and less about the main account. I feel we all just use our various private ones, because that’s where the real friends are and where I can show them what I really want them to look at.”

In South Korea, many study participants create accounts expressly for following K-pop stars and engaging with fandoms, in order to keep this part of their identity separate from other self-presentations. Study participants told us that some people set up Twitter accounts specifically for this purpose: “People keep their secret hobbies on Twitter.” This practice not only helps them to avoid potential embarrassment if it isn’t considered “cool” to be a fan of a particular celebrity, but also provides a means to enjoy relationship building with a wider community of people who share their passions or interests.

Finally, some participants also create completely private or “secret” accounts with no followers at all, using it as a “personal diary” to store digital memories or journal their thoughts.

At a more micro level within the apps, teen participants are adept at adjusting the boundaries around audiences through the meticulous use of settings like “Close Friends” on Instagram. This feature’s design introduces an audience binary that does not always align with the nuanced social ecosystems teen participants belong to. As such, we observed participants regularly readjusting the Close Friends list for individual posts, adding or removing users to ensure that their content will reach a specific set of people each time. Doing so is an effective, albeit involved way to navigate audience collapse, but it also serves a secondary purpose: it allows them to play with social inclusivity and exclusivity, whereby “in group” status can cultivate relational bonding with specific individuals or groups.

These behaviors illustrate that despite the challenges of flattened and bundled audiences online, study participants find ways to unbundle them, express themselves, and develop shared experiences with their various social groups. Although study participants’ public-facing profiles often contain no posts, a significant amount of posting activity is taking place on private accounts or on those with very select audiences or specific purposes.

Context Collapse Dimension #2: Distortion of Time

Time operates differently online—the boundaries between the past, present and future are blurred. As Brandtzdaeg and Lüders (2018) noted, time no longer possesses a linear or sequential nature on social media: the past does not stay in the past, the present doesn’t stay in the present. This characteristic of digital spaces contributes to context collapse, which Michael Wesch highlighted in his 2009 study of the webcam and YouTube videos: “The images, actions, and words captured by the [webcam] lens at any moment can be transported to anywhere on the planet and preserved (the performer must assume) for all time. The little glass lens becomes the gateway to a black hole sucking all of time and space—virtually all possible contexts—in on itself.” This temporal blurring affects how users manage their identity and performances, since it forces people to consider their self-presentation over time and not just in the moment (Brandtzdaeg and Lüders 2018; Wesch 2009).

Time distortion online results from a number of properties inherent to social media, such as what boyd (2008) terms “persistence” and “searchability.” Persistence refers to how “online expressions are automatically recorded and archived”, meaning that the potential to view or interact with what has been digitally inscribed extends in time far beyond the moment of inscription. Searchability refers to how digital content can be retrieved by a user at will. These characteristics of online interactions stand in stark contrast to the synchronicity and ephemerality of offline interactions (boyd 2008, 2010; Hogan 2010). One participant we spoke to in the UK articulated this in her reflections on Snapchat, an app where chats aren’t saved: “Snapchat is the most like real life…in real life, if you have a conversation, it disappears afterwards.”

Teen participants are highly conscious of the “persistence” of digital recordings, but they characterize this phenomenon even more strongly, consistently referring to interactions, particularly posting to feeds and messaging, as “permanent”. The permanence of inscriptions online runs counter to the fact many teens in our study simply desire to connect over trivial, everyday moments with their friends. As Jenny from Spain told us, “I do have a main account where I post things that are actually nice but most of the time I like sending pictures of something like me brushing my teeth to my friends.” Teen participants intend for the sharing of the regular and mundane to be something ephemeral, a passing comment rather than a mark of their identity for years to come.

The permanence of social media content is particularly evident to teen participants given the amount of change that they experience during the journey of adolescence, both personally and socially. As many developmental scholars have noted (McNelles and Connolly 1999; Kilford et al. 2016), the teenage years are characterized by a significant number of transitions, both micro and macro, and teens are continually navigating the shifting landscape of identity formation and social maturation. Against this backdrop, the effects of time distortion on social media are felt very acutely by teen participants, to the point that terminology around these effects have become common parlance. For example, South Korean teens from our study use the term “dark history” to describe the idea that anything from your past can at some point “pop up and embarrass you” in the future. The affordances of algorithms make content not only searchable, but “discoverable” at any time (Abidin 2021).

The Distortion of Time Leads Teen Participants to Hack Time

In the midst of time distortion online, teen participants utilize three principal techniques to counteract or mitigate the effects of online permanence and discoverability: using ephemeral features for daily interactions, carefully curating publicly posted memories, and fashioning out spaces for private nostalgia. In general, the mindset of study participants is to develop content in the present with a view towards the future.

While the social media profiles of teens in our study often appear derelict, containing no signs of their everyday lives, other spaces online are teeming with regular activity. Indeed, for the majority of daily interactions, teen participants gravitate to platforms or features that facilitate ephemerality and imitate the nature of offline conversations. For example, messaging features on Snapchat such as disappearing photos and dynamic chat groups have led to it becoming the primary domain of many UK and Spanish participants’ social lives online. The ephemeral nature of the content in these spaces reduces the sense of pressure associated with more permanent posting to social media feeds. Participants across markets referenced ongoing “photo chains” of random pictures of the floor or a portion of their face that they would send to a friend. As one participant said, “You just can’t stop sending them!”

Although teens in our study largely avoid online permanence, there are occasions in which they do choose to share content in more public, persistent spaces. This is typically in relation to memories. Several participants spoke about reserving the act of posting on their profiles for special moments that they felt particularly proud of. However, given that teen participants are experiencing constant changes as part of growing up, many of them routinely engage in the practice of “cleaning” their profiles by deleting published memories that do not match how they want to present themselves in their current life stage: “Once a month I go through my Instagram highlights and clean them up” – Woo-Jin, South Korea. Thus, their empty profiles do not necessarily signify that they have always been empty, but rather that participants are monitoring and editing them regularly to continually adjust their self-presentations.

In addition to sharing their memories with other people, study participants also carve out more private spaces for personal nostalgia that enable them to look back on their past and relive certain moments in time. For example, participants archive posts on Instagram or create and save drafts on TikTok which are visible only to themselves. Participants in our study often have hundreds, even thousands of drafts, demonstrating a highly active engagement with social media, despite any evidence of public broadcasting. As Lucy from the UK put it, “I have hundreds of drafts and just one post. Drafts are an easy way to look back on time with my friends without the pressure of posting.”

Study participants use draft spaces as “enhanced camera rolls” that also allow them to experiment with different modes of self-presentation: “I save the ones I like the most to my ‘Favorites’—the videos that I want to go back to” – Estella, Spain. Although TikTok is known as a public broadcasting-centric platform, the teen participants we spoke with do not actively, regularly post there. Most often, they enjoy scrolling through their draft videos or photos on their own or with the friends they had recorded them with to reminisce and bond over shared experiences. Stephanie from the UK had made this a highly regular practice: “I love making TikTok videos and just keep them in my drafts. I have over 4000 drafts and I go back and watch them all the time and go ‘awww’, it’s so fun.”

Participants’ strategies for hacking time allow them to actually use time collapse to their advantage: whereas offline interactions are truly fleeting, generating digital memories allows them to traverse time and space within their own private time capsules. Our research demonstrates how teen participants shift fluidly between varying degrees of temporality online. They hack the architecture of social media platforms to both remediate the effects of online permanence in public spaces, and also to leverage the temporal affordances of these technologies for both social and reflexive practices.

Context Collapse Dimension #3: Instability of Meaning

Even in everyday communication, we often say that “message received is not always message sent” and that our intended meaning can be “taken out of context”. However, digital spaces like social media amplify and accelerate the reinterpretation of meaning in profound ways. Previous scholarly work has not tended to focus on “meaning” as a part of context collapse, but we argue that it should be included as a dimension. Teen participants are highly aware of its instability online—a piece of content can circulate in unpredictable ways and take on a life of its own. Once teen participants put something out into the world of social media, they know that it can be difficult or in some cases even impossible to be fully taken back. Even if they later decide to delete it, it may have already been screenshotted or disseminated. In any digital space, from the most public to the most private, there is always the possibility that one’s message can be reshared and reinterpreted by someone else. As Luke, 17, from the UK warned us: “Social media is pressure: everything you say can be controversial and taken out of context.”

boyd’s property of “replicability” (2008) is an example of the instability of meaning, where the ability to duplicate a digital record allows a user to transfer it from one context to another. Abidin (2021) updated this property to “decodability”, referring to how “content can be duplicated but may not be contextually intelligible”. However, we suggest that for our study participants, the most salient understanding of this facet of context collapse is “remixability”. Platforms such as TikTok have ushered in a new set of tools, behaviors, and norms that have remixing at their core. These foster creativity and playfulness, but also magnify the effects of context collapse because of how easy it is for users to quickly edit, reinterpret, and redistribute other users’ content (Abidin 2020; Leaver et al. 2020; Klug et al. 2023; Wei 2021).

Furthermore, with an abundance of social media apps, there is significant circulation and cross-pollination of content between and across them. A piece of content with a particular meaning that is created on one app can end up on a completely different app with its own distinct set of norms and audiences. Through the combination of algorithmic technology and users’ ability to remix, reshare or bring attention to content (for example, via comments and likes), a double context collapse can result: there is the broadcasting of content to unknown audiences, as well as the instability of meaning that can result from these audiences’ interpretation or reinterpretation of the content. Ji-Won in South Korea described how this reality made her reluctant to post selfies: “People might screenshot my selfie and use it in the future. They might evaluate or judge my look. In the future the selfie might not look nice.”

From the perspective of study participants, we also heard that social media platforms destabilize meaning because of the tensions that exist between being interpreted as “authentic” or “cringey”. While the common rhetoric of self-presentation is “just be yourself”, they find this maxim constraining and challenging to realize, given that their content can be remixed and presented in different ways by others on the platform, and also because of the flattening of audiences online. They understand that people have various opinions on what constitutes the desired level of authenticity, that is, alignment between one’s real life and their online expression. As Marwick and boyd (2010) have noted, “there is no such thing as universal authenticity; rather, the authentic is a localized, temporally situated social construct that varies widely based on community.” As such, teen participants feel like they are walking an authenticity interpretation tightrope, often leading some of them to avoid posting on social media feeds altogether. However, this doesn’t stop them from finding other ways to express themselves.

The Instability of Meaning Leads Teen Participants to Play with Meaning

It was particularly fascinating to explore how teen participants played with meaning in response to the frequent decontextualization of what they shared online. To preemptively shield from being misinterpreted, we noted how study participants intentionally worked to create distance between themselves and their “messages” in online spaces. They often use a variety of image, sound, editing tools and app settings in service of three important strategies: decentering the self, subversion of platform norms, and indirect communication.

The rise of influencers alongside affordances for public broadcasting has led to a hyper-focus on personal brand, curated aesthetics, and self-promotion on social media, often in the form of “selfies” (Abidin 2016; Marwick 2015). Within this context, we observed how study participants across markets sought ways to deflect focus from the self when sharing personal or biographical content. Although they want to provide meaningful glimpses of their personalities, interests and special moments, they don’t want to come across as vain or self-absorbed, or be associated with influencer culture.

As a consequence, we encountered numerous examples of selfies that were blurred or where faces had been intentionally obscured, as well as a preference for photos of scenery that gave indications of participants’ environments but didn’t feature themselves explicitly. Creating some level of vagueness or distance between the self and what is shared helps protect against reinterpretation of personal content, essentially facilitating scenarios of “plausible deniability”. Another practice we observed was using black cover photos for Instagram highlights, labeled with ambiguous titles or no titles at all. By subduing the aesthetics of these photo highlights, teen participants hope they might “fly under the radar” (Abidin 2021), more likely to only be noticed by friends “in the know”.

The second strategy for playing with meaning is the deliberate, but often subtle, subversion of aesthetic and behavioral norms on platforms. A number of participants discussed engaging in “anti-curation” practices on secondary profiles, created to intentionally post photos or videos that do not align with the “typical” aesthetics of apps such as Instagram. We noted that participants loved to use tactics like these, as well as irony, satire, and humor to reclaim the context and meaning of shared content. For example, memes often create a set of fast moving “in-jokes” that can be only understood by insiders but not by the broader public.

The third form of playing with meaning is indirect communication. This strategy allows teen participants to create a protective layer of ambiguity while they seek to initiate or strengthen social relationships. For example, study participants use BeReal app’s structure for reciprocal photo sharing to discreetly find out what their friends are doing. Instead of posting a photo to share something about themselves, they upload a random one just to trigger the ability to view others’ posts. This subtle form of engagement is preferred to asking their friends outright, “What are you up to?”

Participants also go to great lengths on other social media apps to communicate indirectly with or detect interest from romantic crushes. On Snapchat, one participant, Mariela, UK, explained that she used the app’s settings to add her crush to a “group” that contained no other users, allowing her to send him a specific photo without him knowing that it wasn’t sent to anyone else. Meanwhile, on Instagram, Sofia, Spain, described a well-thought out process of posting a photo, archiving it, and then unarchiving it, at which point the algorithm would no longer push the photo to people’s feeds. She would then wait to see if her crush liked the photo, as that signaled he had purposefully visited her profile, rather than seeing it on his feed. In a slightly less involved process, Jared, UK, described turning his “Ghost mode” location feature on and off on Snapchat, to generate intrigue about his whereabouts and potentially invite inquiries.

Finally, we also observed many forms of encoding messages online, such as social steganography (Abidin 2021; boyd and Marwick 2011), the practice of hiding messages in plain sight. For example, sharing song lyrics or even overlaying a song onto a post enables teen participants to communicate a message that only a select few in their social media audiences will understand, as it is tied to some kind of shared experience or insider knowledge. This strategy allows participants to ensure their message will be interpreted correctly by the intended individuals, and it also simultaneously enhances their social bonds with those individuals. Playing with meaning was truly a playful and meaningful strategy for so many of our teen participants.

Context Collapse Dimension #4: Conflicting Purposes of Platforms

Throughout our research with teen participants, we were struck by not only their levels of self-awareness when it came to self-presentation, but also their awareness of how different platforms influence their interactions.

Social media apps often seem to have conflicting purposes and norms for their use, resulting in tensions around the sorts of behaviors or interactions that users should engage in. Platforms are simultaneously spaces for sharing personal updates, shopping for products, following celebrities, interacting with official school accounts, and advancing social causes, which introduces uncertainty and complexity as to what they are truly for and how they should be used.

While some scholars have previously examined the ways in which platform norms impact people’s social media use (Abidin 2020; boyd 2014; Miller et al. 2016; Szabla and Blommaert 2020; Wexler et al. 2019), there has been less scholarly consideration for how the conflicting purposes of platforms also represent a key dimension of context collapse, particularly for teens navigating today’s social media landscape.

Daniel Miller et. al (2016) posited that “we should be careful in presuming that there are properties of the platforms that are responsible for, or in some sense cause, the associations that we observe with platforms”, but we observed that many of our teen participants were vocal about the active role of the app architectures themselves. Across markets, participants are conscious of “the algorithm” dictating what they watch and how long they spend on the app. They are cognizant of posts being monitored, accounts being “shadowbanned”, and certain content or interactions being celebrated more than others. Teens in our study often feel that platforms expect them to fulfill certain “roles” that they aren’t always willing to play:

I used to want to be an influencer, but then I kind of gave up. I made £800 from TikTok from advertising people’s products. But then I got shadowbanned. I was tired anyway with how the platform was continually trying to get me to make content.

—16, F, UK

This intrinsic awareness of the role the app plays in their interactions can also be viewed in relation to the rise of influencer culture and the attention economy that was peaking as this generation of teenagers arrived on social media. Teen participants are aware that social media is as much of a commercial space (where businesses operate and generate profit) as it is a deeply personal and social space (where meaningful connections with friends, peers, and even themselves occur). The conflation of these two seemingly incongruent purposes is a reality that plays out in each day-to-day interaction for teen participants on these apps: at what point does posting photos for my friends to see become a monetizable interaction? At what point am I scrolling for enjoyment or scrolling because of the algorithm? Maria from Spain described this dilemma and her response this way: “I used to spend so much time looking at influencers so I created a new account just for adding my friends, and none of the influencers.”

Academics such as Marwick and boyd pointed out as early as 2010 that spaces involving “micro-celebrity practice” such as Twitter combined “public-facing and interpersonal interaction”, the result of which were “new tensions and conflicts” for the networked audience within it. They went on to ask “if ‘public’ space is becoming synonymous with ‘commercial’”, a question increasingly at the forefront of teen participants’ experiences online today. Participants consistently, and consciously, grapple with the conflict between public and personal, as well as “authentic” interactions and commercialized ones. Arriving on and operating within a social media platform means a collision between these binaries, and study participants expressed growing uncertainty about apps whose commercially-driven “inner-workings” felt difficult to understand.

The Conflicting Purposes of Platforms Leads Teen Participants to Engage Intentionally with Platforms

As teen participants encounter conflicts between personal and commercial purposes of social media, as well as the influence of algorithms on their interactions, they think critically about how to engage with platforms from a place of agency and intentionality.

When study participants spoke about the various platforms they used, they often portrayed apps as “actors” in their interactions. In this sense, they humanize and personify apps, which helps them to rationalize decisions and gain a sense of agency through the promise of a two-way relationship. The “algorithm” is an entity that they can “get to know”, an entity with which they can negotiate, influence or shape (Gillespie 2014). It monitors and evaluates their content, and teen participants modify their content to avoid the app’s “gaze”.

This strategy can be understood as a means by which teen participants attempt to contextualize the intentions of apps they are using. They feel they have to fill in the gaps between what they believe platforms can do (shadowbanning, etc.) and what platforms actually do. In the absence of the level of transparency study participants expect from social media platforms, engaging with an “app” as an “actor” helps them to define a role that feels “authentic” to them: one teen from our study purposefully created seven different accounts on Instagram in order to generate “seven different algorithms” that catered to her diverse interests. Other teen participants use platforms like TikTok through their phone’s browser rather than through the app. In doing so, they feel they can still enjoy using the app, without it learning too much about them and capturing more of their attention.

For some study participants, the perceived pressure they feel from apps to behave in a certain way leads them to delete the apps entirely. As one teen from the study recounted, “I got rid of TikTok because I felt there was a lot of pressure to make videos and that made it less fun. That kind of all went away when I deleted it—there wasn’t as much pressure anymore.”

Teen participants’ response to the collapse of platform purposes—particularly the conflict between personal use and commercialized influencer culture—is particularly evidenced by their gravitation away from posting-oriented platforms and more towards messaging and gaming platforms:

“I don’t see any need to be constantly sharing [things on social media]. If I have to share something, I’ll send it to other people through messages”

– Pablo, Spain

For many teens in the study, apps like WhatsApp, Snapchat and Discord, which center on messaging with friends and family, are foundational, while apps which focus on content, like TikTok and Instagram, are more optional.

This reorientation towards smaller circle social interaction plays out hand in hand with the phenomenon of empty social media profiles across many different apps. Conscious that their posts to social media feeds are subject to commercial purposes or unclear algorithmic influence, teen participants opt for interactions that feel immune to these processes. In some cases, participants were vocal about their outright rejection of public broadcasting, while for others, their strategic shifts in behavior were more subtle. Throughout our study, we witnessed a broad inventory of creative strategies that teen participants employ to mitigate multidimensional context collapse, and even in some instances, use context collapse to their advantage.

Conclusion

This paper has provided a foundational understanding of teen social media use through historical, theoretical, and international ethnographic lenses. While a historical view shows that context collapse has always been implicit in online interactions, our ethnographic research reveals that online context collapse is arguably more prevalent and complex than ever and that teen participants operate by default from a place of high awareness and attunement to this phenomenon.

We have argued for an expanded understanding of multidimensional context collapse that encompasses not only the flattening of audiences and the distortion of time, but also the instability of meaning and the conflicting purposes of platforms. Through our context collapse framework, we have provided a lens that can help future ethnographic practitioners understand young people’s experiences with social media more deeply.

The teen participants from our study operate with a mindset of private and ephemeral by default, and public and permanent through effort (only with deliberate strategies). This current paradigm often appears to present as an avoidance of “posting”, but does not necessarily imply an avoidance of social media. On the contrary, our research reveals a wealth of generative strategies that participants use to meaningfully engage with social media on their own terms. It is our hope that our framework for context collapse can also aid future practitioners in uncovering the adaptive and innovative behaviors of users who navigate context collapse online.

Finally, in revealing the negotiations between users and context collapse, at times tense, at others playful, we wish to challenge the notion of social media as either a utopian or dystopian technology, two polarizing extremes that are often popularized in public discourse. Our research demonstrates that both users and social media technology are active agents in the shaping of online experiences (Abidin 2021; Davis and Jurgenson 2014; Gillespie 2014; Szabla and Blommaert 2020), and as such, this two-way relationship creates a far more complex reality than may be initially assumed. Social media has the capacity to amplify a range of content and experiences, both positive and negative (boyd 2014), but people also have an incredible capacity to navigate, strategize, and reclaim these online spaces for meaningful purposes.

As we look forward to the next era of social media, we consider both the past and the present, and ponder, will it continue to be called social media by the next generation of users? Where might their strategies lead, and how will these shape the future of these platforms? One thing is for certain—we must continue to generate new approaches for meeting young people where they’re at, taking notice of what they want to share, their challenges, and their responses. We should consider how we can more proactively and thoughtfully design platforms that support what is important to them. We conclude not with a prediction but rather an open question for the community: how can we pay attention to both what is said and also unsaid, done and not done? What are people communicating when they post, but also, what are they conveying when they don’t?

About the Authors

Kristin Sarmiento is an applied cultural anthropologist consulting for Stripe Partners. She specializes in using ethnographic approaches to understand the values and needs that underlie human behavior, and applying these insights to inform business strategy, decision making, and product development. Notable projects include foundational and UX research with youth for tech innovation companies. She holds a BA in Anthropology (double minor in Linguistics and Spanish) from Mount Royal University, Canada. kristin.sarmiento@stripepartners.com

Isabelle Cotton is a digital anthropologist and social researcher. Her work centers around using anthropology as a transformative tool of empathy in digital spaces. Before leading on research at Stripe Partners, she worked at a Gen-Z insights agency that platformed minority voices. Especially when working with young audiences, she prioritizes creating a research process that is mutually beneficial for both clients and participants. Isabelle holds an MSc in Digital Anthropology from UCL. isabelle.cotton@stripepartners.com

Josh Terry is a consultant with a background in anthropology and history. He is particularly interested in the social and cultural dimensions of emerging digital spaces and much of his current work focuses on younger generations’ relationships with digital platforms. Josh holds an MSc in Social and Cultural Anthropology from UCL. His work and studies have been driven by a fascination in the way societies, cultures and the relationships people form both shape and are shaped by emerging technologies. josh.terry@stripepartners.com

Lea Ventura is part of a team at Instagram that supports the responsible growth of teens on the platform. With over 10 years of experience as a licensed child and adolescent clinical psychologist, Lea has a strong background in mental and behavioral health. She holds a PhD in Clinical Psychology and an undergraduate degree in Cognitive Neuroscience. At Instagram, Lea combines clinical expertise with UX research to promote wellbeing in tech and ethical & supportive product development for younger users.

Shayli Jimenez is a Senior UX Researcher at Meta’s Reality Labs, specializing in developing research-based strategies for emerging technologies like GenAI and platforms such as Horizon and the Metaverse. With almost 10 years of experience working across Meta, Shayli excels in identifying priorities and delivering top-tier research insights. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Public Communication and Graphic Design from American University.

Notes

We wish to thank Annie Lambla (Lead User Researcher, Coloplast), Cath Richardson (Partner, Stripe Partners), Simon Roberts (Partner, Stripe Partners), and Kristin Hendrix (VP, Head of Research, Instagram) for their time and thoughtful comments in reviewing the drafts of this paper.

This work does not reflect the views, opinions, or official position of Meta. This paper is not based on any internal log data, quantitative studies that size or show social media behaviors at a population level, or studies about adult users.

[1] We recruited a representative mix of SECs, ethnicities and genders from urban settings (cities and suburban regions), as well as a mix of social media user types (different apps, different levels of engagement).

[2] All participant names have been pseudonymized in this paper.

References Cited

Abidin, C. 2015. “Communicative ❤ Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness.” International Journal of Communication 9:21–39.

Abidin, C. 2016. “‘Aren’t These Just Young, Rich Women Doing Vain Things Online?’: Influencer Selfies as Subversive Frivolity.” Social Media + Society 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051166413

Abidin, C. 2020. “Mapping Internet Celebrity on TikTok: Exploring Attention Economies and Visibility Labours.” Media International Australia 177(1): 30–45.

Abidin, C. 2021. “From ‘Networked Publics’ to ‘Refracted Publics’: A Companion Framework for Researching ‘Below the Radar’ Studies.” Social Media + Society 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/205630512098445

Asokan, A. 2008. “The Space Between Mine and Ours: Exploring the Subtle Spaces Between the Private and the Shared in India.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 1:175–191.

boyd, d. 2008. “Taken Out of Context: American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics.” PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

boyd, d. 2014. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

boyd, d., and Marwick, A. 2011. “Social Privacy in Networked Publics: Teens’ Attitudes, Practices, and Strategies.” Journal of Communication 61(4): 102–121.

Brandtzaeg, P. B., and Lüders, M. 2018. “Time Collapse in Social Media: Extending the Context Collapse.” Social Media + Society 4(1).

Brügger, N. 2015. “A Brief History of Facebook as a Media Text: The Development of an Empty Structure.” First Monday 20(5) https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5423.

Bucher, T. 2018. “If…Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics.” New Media & Society 20(11):4197–4213.

Campbell, S.W. 2013. “Mobile Media and Communication: A New Field, or Just a New Journal?” Mobile Media & Communication 1(1): 8–13.

Davis, L., and Jurgenson, N. 2014. “Context Collapse: Theorizing Context Collusions and Collisions.” Information, Communication & Society 17(4):476–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.888458.

Faulkner, S., and Melican, J. 2007. “Getting Noticed, Showing-Off, Being Overheard: Amateurs, Authors and Artists Inventing and Reinventing Themselves in Online.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 1:51–65.

Gillespie, T. 2014. “The Relevance of Algorithms.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo J. Boczkowski, and Kirsten A. Foot, 167–194. MIT Press.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

Gopffarth, J., Jablonsky, R., and Richardson, C. 2022. “Building Resilient Futures in the Virtual Everyday: Virtual Worlds and the Social Resilience of Teens During COVID-19.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 1:117–136.

Highfield, T., and Leaver, T. 2016. “Instagrammatics and Digital Methods: Studying Visual Social Media, from Selfies and GIFs to Memes and Emoji.” Communication Research and Practice 2(1):47–62.

Hogan, B. 2010. “The Presentation of Self in the Age of Social Media: Distinguishing Performances and Exhibitions Online.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30(6):377–386.

Horst, H.A., and Miller, D. 2012. Digital Anthropology. London: Berg.

Ito, M., Baumer, S. Bittanti, M., boyd, d., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., Horst, H. A., Lange, P. G., Mahendran, D., Martinez, K. Z., Pascoe, C.J., Perkel, D., Robinson, L., Sims, C., Tripp, L. 2010. Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kilford, E., Garrett, E., and Blakemore, S-J. 2016. “The Development of Social Cognition in Adolescence: An Integrated Perspective.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 70:106–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.016

Klug, D., Evans, M., and Kaufman, G. 2023. “How TikTok Served as a Platform for Young People to Share and Cope with Lived COVID-19 Experiences.” MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research 38:152–170. https://doi.org/10.7146/mk.v38i73.128463

Leaver, T., Highfield, T., and Abidin, C. 2020. Instagram: Visual Social Media Cultures. Cambridge: Polity.

Ling, R. 2012. Taken for Grantedness: The Embedding of Mobile Communication into Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., and Smith, A. 2013. “Teens, Social Media, and Privacy.” Pew Research Center, May 21 https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/21/teens-social-media-and-privacy/.

March, W., and Fleuriot, C. 2005. “The Worst Technology for Girls?” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 1:165–172.

Marwick, A. 2015. “Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy.” In The Drama of Social Life, edited by T. Merrin, 107–126. Routledge.

Marwick, A., and boyd, d. 2010. “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience.” New Media & Society 20:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

McNelles, L.R., and Connolly, J.A. 1999. “Intimacy between adolescent friends: Age and gender differences in intimate affect and intimate behaviors.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 9(2):143–159. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0902_2

Miller, D., Costa, E., Haynes, N., McDonal, T., Nicolescu, R., Sinanan, J., Spyer, J., Venkatraman, S., Wang, X. 2016. How the World Changed Social Media. London: UCL Press.

Rangaswamy, N., and Yamsani, S. 2011. “‘Mental Kartha Hai’ or ‘Its Blowing My Mind’: Evolution of the Mobile Internet in an Indian Slum.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2011:285–298.

Schulz, C. 2023. “A New Algorithmic Imaginary.” Media, Culture & Society 45(3):646–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221136014

Senft, T. M. 2013. “Microcelebrity and the Branded Self.” In A Companion to New Media Dynamics, edited by John Hartley, Jean Burgess, and Axel Bruns. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118321607.ch22

Szabla, M., and Blommaert, J. 2020. “Does context really collapse in social media interaction?” Applied Linguistics Review 11(2):251–279. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0119

Wei, E. 2021. “American Idle.” Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.eugenewei.com/blog/american-idle

Wexler, M., Yunzhijun, Y., and Bridson, S. 2019. “Putting Context Collapse in Context.” Journal of Ideology 40(1):3.

Wesch, M. 2009. “Youtube and You: Experiences of self-awareness in the context collapse of the recording webcam.” Explorations in Media Ecology, 8(2):19-34.