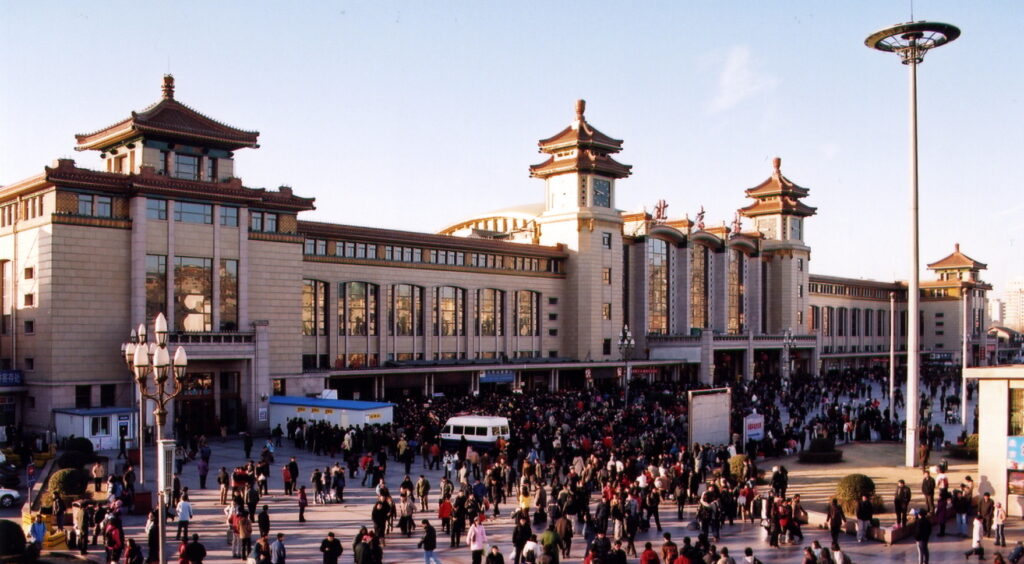

There’s a kind of building found across China that combines a Western-style “body” with a rather incongruous Chinese-style glazed tile roof plonked on top. This style of architecture had its heyday in the frenzy of the Great Leap Forward, when Chairman Mao ordered architects and engineers to design and construct ten gigantic buildings in Beijing in the space of just ten months.

In indigenous Chinese architectural designs, tiled rooves are structurally integrated into the rest of the building through posts and beams. In these 1950s designs, the “Chinese hat” (dawuding, lit. “big roof”) is reduced to a decorative afterthought to give some vague Chinese character to the imported design. Architect Liang Sicheng criticized the mismatched structures as “wearing a Western suit with a Chinese hat.”

Multinationals’ efforts to conquer the Chinese market often remind us of this “Chinese hat” analogy. Many times over the years living and working in China, we have seen marketers, design researchers, innovators, and even ethnographers applying the same methods and analytical tools developed in their home markets.

Despite a genuine desire to understand the people they design solutions for, the efforts of innovators and marketers end up resembling an awkward architectural pastiche, an imported structure glossed with a Chinese veneer. This is the dreaded “Chinese hat syndrome,” which can lead to fundamental misreadings of behavioural complexity in the field.

The truth is, no tool or method alone—ethnographic or otherwise—is sufficient to help us decipher the cultural grammar of a social field we’re unfamiliar with. This is even truer when researchers are pressed with time constraints, as is invariably the case in industry.

This reality calls for us to go beyond existing research plans and frameworks, as Jay Hasbrouck advocates in Ethnographic Thinking, and shift from “Method to Mindset” (review here).

We also need embodied approaches to bring us closer to the social reality around us. This isn’t about some kind of “raw” encounter or experience, but rather requires that we embed in our research an appreciation of institutional, historical and political factors that constantly shape the social field and give meaning to what we see and hear.

This article illustrates the importance of incorporating that contextual knowledge into each step of the research process, from research design and execution to interpreting the data.

Planning the Research: Searching for the Elusive Chinese Consumer

In late 2017, McKinsey belatedly announced the death of “the Chinese consumer,” admitting “there is no longer a single, one-size-fits-all definition of the Chinese consumer.” This should come as no surprise in a continental-scale market of 1.4 billion people and a plethora of regional cultures, ethnic groups, and 300-odd languages.

While “new art youth” (wenyi qingnian) sip lattes in prosperous coastal metropolises that approach and even exceed European cities on many socioeconomic metrics, conditions of their compatriots in interior provinces such as Guizhou may be closer to rural India. Just scratch the surface and the so-called “Chinese consumer” soon disintegrates into a kaleidoscope of different dialects, tastes, temperaments and lifestyles in constant flux.

But corporations persist in sponsoring research on this elusive Chinese consumer, so where and on whom should a researcher focus their study? The typical suggestion is “a Tier 1 and maybe a Tier 2 city,” followed by discussions on generational cohorts and their attitudes to life and consumption in “the city.” Yet if those terms and categories may be appropriate for some countries or markets, they don’t always make sense in China.

For example, outsiders may be disoriented by the fact that people living in “Tier 3” Wenzhou may exhibit more complex wine consumption behaviours than in “Tier 1” Beijing, due in part to Wenzhou’s historical migratory connections with Italy and France.

Likewise, companies frequently assume that individuals of the 1980s (Balinghou) generation share common characteristics, but pay little attention to how these traits intersect with other regional, social and political vectors to create important distinctions between them. For example, interprovincial variations in policy and economic planning may influence aspirations and attitudes to consumption in ways that should not be overlooked when planning fieldwork.

This category-confounding complexity calls for thorough investigation before the research even starts. There is a lot of useful material out there for the patient ethnographer. What works even better, however, is tapping (and budgeting for) local knowledge and resources from the very start rather than only during fieldwork.

Gathering Data: Beyond the Home

In addition to understanding that they will encounter different nuances and intricacies in foreign markets, researchers also need to confront ways in which methods developed in home markets will need tweaking for other contexts.

For instance, in the US, research often takes place in the home because this is seen as a safe space for conversations and allows ethnographers to get a richer understanding of participants’ lives through exploring the interior design, personal belongings and so on.

In China, it is not uncommon for people’s lives to be spread across different family dwellings, each representing a different part of themselves. Multiple generations may live under the same roof and have different notions of privacy. Such spaces are not always conducive to participants sharing personal thoughts.

Even more so than in the US or Europe, we find behaviour and expression within homes to be constrained by the need to play out family roles. Adding to that, participant behaviour (and responses) are deeply influenced by their perceived role within the research dynamic and therefore trust of their visitors, usually built through a highly social and shared context that puts the researcher in a participant role as well.

In China, we’ve found it useful to supplement in-home research with interactions in a space of “play” (wanr) outside the home, centred around a shared activity such as karaoke or eating hotpot. Wanr (lit. “to play”) refers to leisure or passing free time and applies to adults and children alike. As well as helping to build trust and social bonds, wanr space may be less subject to hierarchical dynamics and efforts at image management (face), opening the door to different types of reflection and spontaneous sharing.

In a new country or culture, you may not know which spaces will yield important or unexpected insights. Thus, an attitude of openness and immersion is crucial—even in moments you might initially assume are outside of the research practice.

For example, a couple of years ago, we travelled with a client team to Beijing. They brought a suitcase of energy bars to eat in the field to avoid food poisoning hiccups that could slow down research. But in addition to missing out on the local food delights, they also lost opportunities to gain a deeper understanding of the very social field being studied—in this case, first-hand experience of the daily negotiations and anxieties that Beijingers face in assessing what, where and how to eat.

We find that some of the most valuable insights emerge when least planned—lost on the way, trying to find a house, or speaking to young guys on motorbikes delivering takeaway food. “Embodied” or immersive approaches engage us in shared experiences that allow us to acquire a type of knowledge rooted in the reality around us. Although practical constraints may limit time for immersion in the field, we believe that by following unconventional leads and being open to mistakes we can better empathize with the lived experience.

Interpreting Evidence: Choosing Your Cultural Lens

Sitting in her living room, a Shanghainese woman boasted to her friends about how much she was willing to spend on moisturizer. This group discussion, observed by a visiting researcher and her interpreter, was part of research on notions of beauty for a skincare brand. Prompted by the researcher, the other friends followed by rating their own willingness to spend on beauty products. Each quoted progressively higher values, with every increase eliciting nods of agreement from the others.

Excitedly scribbling values as the price was continuously “bid” upwards, the researcher did not realize that she was in fact witnessing a social dance driven by face. Rather than revealing price preference, these wealthy professionals were trying to outdo each other in signalling willingness to invest in themselves.

Examples such as this show how focusing on data in isolation, without adequate contextualization, can lead to interpretations that are dangerously narrow or distorted.

At the same time, researchers too familiar with the local context might sometimes dismiss significant data as unremarkable. On one project, a team of local researchers in Chengdu overlooked the particular habit of applying deodorants to clothes rather than skin, because they were already accustomed to the practice and understanding that deodorants damage health and skin. By contrast, this stood out as significant to outsiders, leading the team down a fruitful new avenue of investigation into beliefs that underpinned the behaviour.

This points to the value of integrating both emic and etic perspectives, combining team members who can translate across linguistic divides with those who are also attuned to conceptual and cultural differences. We all have a degree of personal bias in our work as ethnographers, as Anna Zavyalova writes here. We each experience the world around us in different ways, based on the myriad of characteristics that make us who we are. It is only normal, then, that our interpretation lenses vary as well.

Data can yield very different insights depending on the cultural “lens” through which it is viewed. We should be wary of forcing data into existing conceptual straitjackets and treating it as evidence.

We couldn’t agree more with Erin Taylor when she calls us “to be more brave at asking ourselves if there is another way of interpreting this data”, but we must also become more creative in introducing new frameworks to the conversation, not only to do justice to what we learn in the field, but because we risk misunderstanding the very social reality that we live in.

Conclusion

As ethnographers, we constantly strive to develop a holistic understanding of social realities that we and others inhabit. However, we should do more to seek new ways to deepen our appreciation of local contexts, ensuring that this understanding is built into the very structure of our research from the foundations upwards.

All too often, the “Chinese hat syndrome” sees local realities squeezed into ill-fitting, imported forms and pre-conceptions. To avoid this, we need to collaborate more closely with researchers, designers and innovators on the ground, involving them from start to finish and not just during our brief forays into the field.

References

Wouter Baan et al, Double-Clicking on the Chinese Consumer, 2017 China Consumer Report, McKinsey & Company.

“Comparing Chinese Provinces with Countries,” The Economist

Simon Roberts & Tom Hoy, “Knowing That and Knowing How: Towards Embodied Strategy,” 2015 EPIC Proceedings, https://doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2015.01057

David Rubeli, “Book Review: Ethnographic Thinking, from Method to Mindset,” EPIC Perspectives, 30 May 2018.

Erin B. Taylor, “Ethnography, Economics and the Limits of Evidence,” EPIC Perspectives, 11 June 2018.

Lindsay Whipp, “P&G Boosts Full-Year Sales Forecast on China Recovery,” Financial Times, 20 January 2017.

Anna Zavyalova, “In Defense of Personal Bias in Ethnographic Research,” EPIC Perspectives, 14 December 2017.

PHOTO: Beijing Railway Station by Mike Stenhouse via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Yuebai Liu leads ethnographic research studies for tech companies and green startups around the world, with a focus on emerging markets. She works with eclectic teams of designers, engineers, artists to understand the human contradictions and develop solutions that matter.

Yuebai Liu leads ethnographic research studies for tech companies and green startups around the world, with a focus on emerging markets. She works with eclectic teams of designers, engineers, artists to understand the human contradictions and develop solutions that matter.

Junni Ogborne researchers and writes about how China is changing, working at the intersection of politics, business and anthropology. He advises multinationals and government clients on how to navigate China’s complex market environment. Junni is also a research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, China’s leading independent think tank.

Junni Ogborne researchers and writes about how China is changing, working at the intersection of politics, business and anthropology. He advises multinationals and government clients on how to navigate China’s complex market environment. Junni is also a research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, China’s leading independent think tank.

Related

Cracking Representations of Emerging Markets: It’s Not Just about Affordability, Kathi Kitner, Renee Kuriyan & Scott Mainwaring

Great Interpreters Inspire Insights, Stuart Henshall

Navigating Relativism and Globalism in Sustainability, Caroline Turnbull

ICT4D => ICT4X: Mitigating the Impact of Cognitive Heuristics and Biases in Ethnographic Business Practice, Tony Salvador, John W. Sherry, L. Wilton Agastein & Hsain Ilahiane

0 Comments