Critical thinkers that we are, researchers are skeptical of buzzwords, one-size-fits all methodologies, and facile business trends. We scowl as ‘ethnography’ is invoked just because someone actually talked with a customer. We say things like, “If you want to be Agile, try yoga.” Even so, we remain deeply committed to the core value of these approaches when they’re done right.

At BeyondCurious, we practice Agile Research. Why did we adapt our research practice to Agile? We did it because we had to. BeyondCurious is an innovation agency that specializes in mobile experiences for enterprise clients. Mobile moves incredibly fast. In order to be an effective, viable, and integral part of BeyondCurious’ mobile design and development process, research has to be done in sync with the rest of the team. And the rest of the team, from strategy and design to development, works in two week, agile sprints.

It wasn’t easy, but we’ve adapted our research methods—from ethnography to UX research—to work within our sprint-based methodology. We have had great results with this approach. Sprints are successive, allowing for rapid pivoting, and enabling the team to follow or jettison lines of inquiry as the product develops. Agile research has allowed us to integrate in-context experience research into everything we do.

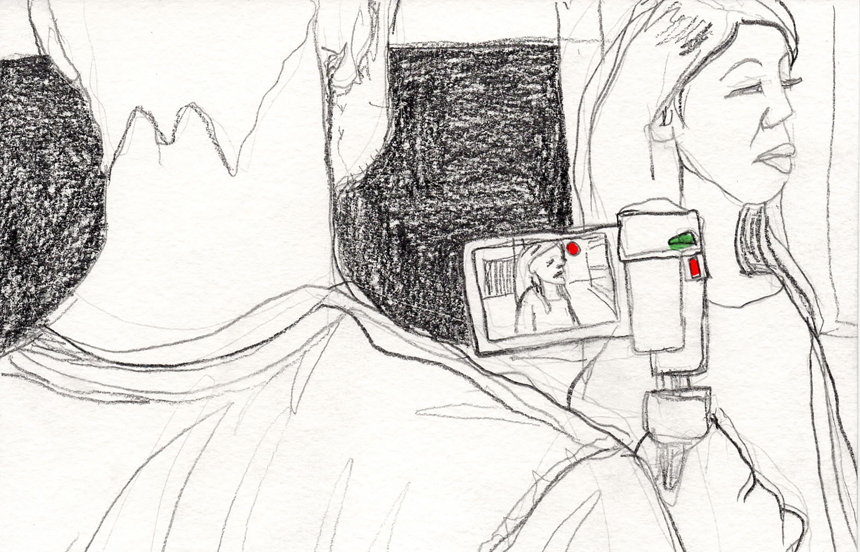

Most of the research we do at BeyondCurious has been contextual UX research on not-yet released experiences. In that context, our hypothesize, test, and evolve approach has been invaluable at helping the business understand where to focus and where to push. However, we have applied the same methodology to ethnographic research.

When we first started contemplating adapting ethnographic research to Agile, we were worried that we would never get appropriate depth if we broke research up into sprints. But then we realized that—just as in our UX research—by breaking ethnographic research down into smaller chunks, research process and findings became more visible to teams and clients, creating a greater appetite for understanding users. The cumulative nature of successive sprints has given us both a broad and a deep understanding of our users whether we’re doing UX or ethnography.

One of the ways we help facilitate breadth and depth is by ensuring that no matter what kind of research we are doing, we review the research to date at regular intervals to pull out key themes, building models of the experience. These models become experience strategy principles or experience models for design and development going forward.

For example, we’ve done a lot of work lately on the intersections between physical and digital spaces, particularly in-store. One of the experience strategy principles that we have developed based on a review of our in-context ethnographic work combined with our UX research is that, particularly in the in-store environment, people don’t read. Instead, they learn through doing. The key to understanding and interest is not relying on people’s intellect, but rather engaging them in experiences that show rather than tell. Think about that the next time you go in to learn about a complex or new product!

Transitioning to Agile has meant more than simply chopping up a more traditional research approach into two-week chunks. We have been rethinking some fundamentals, experimenting with new approaches, and ultimately seeing the researcher’s role and responsibilities in new ways. Here are some of the things we’ve learned (and are still learning) along the way:

Research Approach

- Minimum viable findings: When you only have two weeks to get to meaningful insights, you can’t boil the ocean. You must focus on a specific question or micro area of the experience. Just as in agile software development methodology, in which each sprint ends with the ability to ship a minimum viable product, each of our Agile Research sprints ends with a minimum viable set of findings on a specific area of inquiry. If we’re working on a prototype, the team can take those findings and develop or design a revised experience for the next test. If we’re working on ethnographic research, findings can inform the next round of fieldwork. Minimum valuable findings have immediate and cumulative value.

Recruiting

- Always be recruiting: Every researcher knows that your research is only as good as your participants. But every researcher is equally aware of the difficulty and time involved in recruiting. In order to jump start our recruiting efforts, we’ve built a panel. This helps make sure we always have a pool of participants from which to draw. And for iterative sprints, the recruiting never stops; we’re always looking for participants.

Team

- Pace yourself: Agile research can be both exhilarating and exhausting; think of it like running a marathon in a series of 400-yard sprints. One person can’t and shouldn’t do it alone for any extended period of time. If you are conducting a series of iterative Agile Research sprints, you have to protect the team by setting a schedule that is reasonable and repeatable. Team mix is also key; you must have both continuity (to minimize ramp up) and new blood (for fresh eyes and to minimize burn out).

Research Planning

- Play hopscotch: One of the benefits of working in lean, integrated teams is that, in contrast to traditional waterfall development, things can go very fast. There’s no waiting around for a handoff; parallel processing and development is possible. So, for example, on bigger UX research projects, where we are collaborating with multiple teams, we can do our Agile Research in a hopscotch pattern, skipping ahead and back, depending on which aspects of the prototype are ready for testing. Our non-linear design and development process means we can do continuous research sprints without a lot of waiting around, facilitating faster, more efficient development.

Tools

- Don’t reinvent the wheel: One reason we have been able to adapt lean methods to qualitative, contextual research is by leveraging existing frameworks—including tools, technologies, and templates—as often as possible. We are constantly searching for ways that technology can help us be more efficient. To this end, we do everything from using online recruiting tools like ethn.io to using applications like Stormboard for collaboration and Flipboard for knowledge sharing. We like dScout for digital diaries, inVision for prototype testing, and Skype or Join.me for remote usability testing. But we are always looking for new tools (suggestions appreciated). Because BeyondCurious is a cloud-based company, it’s easy for us to experiment with new tools, jettison those that aren’t all that, and adopt the ones we like.

Mindset

- Translate research into solutions: In many agencies, researchers come up with findings and leave solution building to designers, strategists, and marketers. But in a fast-paced mobile environment, it simply does not make sense to ask someone else to interpret your findings—and hope they do it correctly. We know the implications of our findings better than anyone. So we’re not afraid to put on our design hats, or our strategy hats, or our marketing or UX hats. In fact, it’s critical that we are able to translate our findings into experience strategy principles, recommendations, and action plans that can be quickly implemented and tested.

- Say yes: Another reason we’ve been able to shift to an agile approach to research has a mental shift. Simply put, when faced with a research question, area of inquiry, or limited time frame, instead of saying no, we find ways to say yes. That mental and attitudinal agility has been just as important as the tools we use to enable our Agile Research methodology. The openness, flexibility, ability to pivot, and rapidity of insights generation that Agile Research enables has helped everyone from clients to internal teams know their target users better.

Methodology

- Make evolution a constant: In the course of evolving our approach to Agile Research, we’ve learned some things about what is successful and what is not successful. We apply our test-and-learn philosophy not only to the projects on which we are working and the models that we have built, but also to the methodology itself. We’ve tried a lot of different things, and continue to refine and evolve the methodology.

On that note, if you’ve gotten to the end of this article and you have some suggestions or insights from your own agile or micro-research process, we would love to hear them. Please leave your thoughts in comments below!

*Illustrations by Carrie Yury

0 Comments