Case Study—This case study highlights the value of ethnography in changing a client’s perspective. New Zealand’s productivity has been deceasing, and the government wants to reverse that trend. Empathy’s government client believed that macro-level forces were having a major impact on the productivity of small businesses, and wanted to suggest ways for small businesses to directly combat those forces. Empathy conducted ethnographic research, and the results required the client to change their perspective. While the government client saw increased productivity as a means to increase the standard of living, ethnographic research revealed some small businesses see increased productivity as a threat to their values and standard of living. If the government wanted to increase productivity, they were going to have to change tact completely and start talking to and supporting small businesses in a way that took their fears, motivations, beliefs and values to heart.

Keywords: ethnography, small business, productivity, government, perspective

CONTEXT

Client Context

A nation’s productivity is routinely linked with its standard of living and its ability to improve wellbeing for the people who live there. Unfortunately, New Zealand’s productivity and thus standard of living have been dropping compared to other nations. The New Zealand Productivity Commission claims that New Zealand has slipped “from once being one of the wealthiest countries to now around 21st in the OECD.” It claims: “New Zealand has a poor productivity track record and lifting productivity is a key economic challenge” (Productivity Hub 2015).

The New Zealand government wants to increase the country’s productivity — how efficiently an organisation can turn its inputs, such as labour and capital, into outputs in the form of goods and services. The New Zealand Productivity Commission was created by an Act of Parliament in 2010, “to provide advice to the Government on improving productivity in a way that is directed to supporting the overall well-being of New Zealanders.”

The Commission and other interested parties have been investigating why New Zealand’s productivity is so low compared to the past and to other OECD nations, and what can be done about it. Lately, focus has shifted to include productivity within the country’s small businesses.

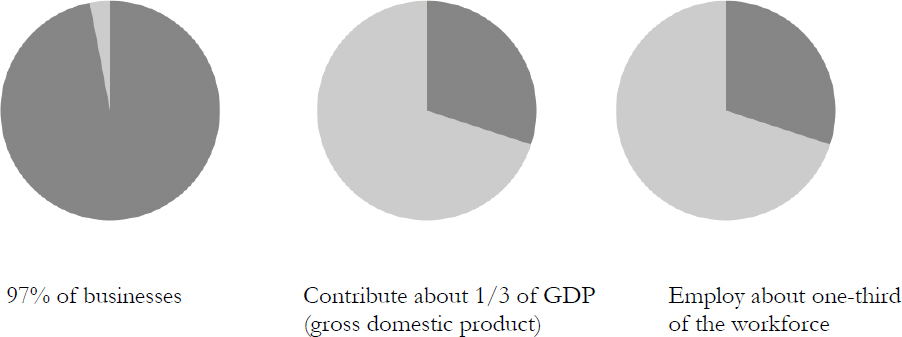

In New Zealand, a ‘small business’ is typically defined as one having fewer than 20 employees (MBIE 2017). Ninety-seven percent of New Zealand’s businesses are small by this definition. Further, it is estimated that 70% of New Zealand businesses have zero employees. Small businesses currently contribute about a third of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), and employ about a third of employees (MBIE 2017). They are a significant component of New Zealand’s workforce and economy.

Small businesses in New Zealand

A team within the New Zealand government, referred to as BG, are responsible for helping small businesses succeed from start-up to fully established and to achieve their definition of success. BG helps government policy makers and service owners to understand and design policies and services for small businesses, and provides a website and other resources for the small businesses themselves. The team sits within the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Together, the Productivity Commission and BG were keen to see if they could better support small businesses to lift New Zealand’s productivity.

Key Players in this Case Study

The New Zealand Productivity Commission. An independent Crown entity who provides advice to the Government on improving productivity, directed to supporting the overall well-being of New Zealanders.

BG. The client. The government team responsible for helping small businesses succeed from start-up to fully established and to achieve their definition of success. Part of the government’s Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. The primary client on this project. The project lead and champion at BG is a recent MBA graduate with a passion for productivity and business performance.

Empathy. A business design studio. Uses ethnography, design and business strategy to uncover powerful needs and insights around latent opportunities, leading to innovation. Works with the private and public sector. Works extensively with the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Is the customer-centred design and delivery partner for BG, responsible for shaping and extending the value offered by the BG website.

Wider government. A term used to refer to government stakeholders in the project beyond BG.

Small business participants. The small business employers and employees with whom we conducted ethnography, and whose productivity we are ultimately trying to improve.

PROJECT BRIEF AND SET-UP

Defining Productivity

BG and the Productivity Commission both want to increase the productivity of small businesses.

BG initiated a project to create online tools and resources for small business owners and operators. The champion of the project within BG briefed the Empathy team.

The first challenge for Empathy was to understand the definition of productivity. Empathy asked BG, who asked the Productivity Commission and also one of the top government economists. Each had a slightly different definition. Eventually, the team settled on productivity being how efficiently an organisation can turn its inputs, such as labour and capital, into outputs in the form of goods and services.

Empathy wondered how small businesses would define ‘productivity’.

Agreeing a Research Focus

The government had largely focused its efforts to understand and increase productivity on macroeconomic forces. Examples included distance to global markets, lack of technical diffusion, a shallow capital economy, and lack of competition. That thinking, combined with discussion of productivity in academic literature and MBA-type sources, had transferred to thoughts about small businesses. The suggestion from wider government and BG was that these macro-level causes of productivity could be considered at a business level, and corresponding business-level interventions created.

For example, one perceived macro-level cause of New Zealand’s low productivity is a lack of technical diffusion. New Zealand businesses are not staying up-to-date with, and adapting to, the newest technical innovations from other countries, such as robotics or internet of things. BG wondered whether Empathy could identify ways that small businesses could implement meso or micro solutions to overcome the macro issue. An example they gave Empathy was that small businesses could tailor hiring strategies to recruit employees from “frontier regions,” such as health companies recruiting talent from the medical innovation frontier of Boston, USA. The following excerpt is from the client’s brief to Empathy. It outlines the client’s expectations about the kind of strategies they expected small businesses to implement in order to improve their productivity.

Macro force: Technical Diffusion

Strategies to note in relation to the adoption of new innovations:

- Are firms using governance eg. a board that have people in these areas?

- Are firms seeking Mentors with skills in these areas?

- Are firms proactively researching trends in the industry and ways to stay up to date?

- Are firms using hiring strategies to compensate? (eg from overseas)

- Are owners / managers attending events and traveling to seek these out?

- Is there an active resource strategy and adoption strategy?

- Do they have an R+D lab to generate their own innovation if shut out from global trends?

BG expected Empathy to conduct research with small businesses. They hoped Empathy would look at ways in which the macro-level causes of productivity were at play at a business level, and whether the businesses were using any of the pre-defined strategies to overcome the negative forces. If the businesses were not using the pre-defined strategies, BG could suggest those strategies to small businesses via the website, prompting new ways to combat the macro-level issues and improve small businesses’ productivity. Further, BG suggested that raising small businesses’ awareness of macro-economic factors would in itself help them to become more productive.

Empathy was worried about this approach to the creation of interventions to increase small business productivity. They were skeptical that raising awareness of macro-economic factors would provide any actionable information for small businesses, or that identifying and highlighting unused strategies from a predefined pick-list would engage and aid business operators.

Instead, Empathy wanted to design interventions specifically for New Zealand’s small businesses. They first wanted to understand the perspective of small businesses. What does ‘productivity’ mean to small businesses? How interested are they in increasing their productivity? What actions are they already taking? What do they perceive is standing in their way? From there, Empathy argued they would be better able to design tools and resources to support small businesses, because the client could base those interventions on the small businesses’ point of view.

Empathy did not want to focus on macro-level influences. They argued strongly for an ethnographic approach that enabled an understanding of productivity from the small businesses’ point of view.

Empathy explained that focusing on macro-level influences and pre-determined strategies was presumptuous and dangerous. It presumed that macro-level forces were the most negative influence on small businesses’ productivity, and that the only strategies used were those pre-determined. By hunting for those specific things in the field, Empathy might produce biased results — looking for impact of a specific macro-level force or implementation of a specific strategy might lead the team to see things that were not strictly present. Further, Empathy might not see if other forces were having an impact, or firms were employing other strategies.

By being open to what they might find, forces and strategies would emerge from the fieldwork — both those actually at play, and those the small businesses think are at play. Further, by seeking to understand the businesses’ context and perspective, Empathy would be in a much better position to design content and tools to resonate with businesses and genuinely suit their needs.

Finally, Empathy referenced previous work for the client, which included ethnography for and subsequent design of a successful and high-profile tool that helped small business employers to create plain English, legally-binding employment agreements for their workers.

This was a major moment for the project team. Empathy was asking BG to step away from the prevailing approach to productivity improvement adopted by wider government. Empathy was also asking the BG project champion to set aside his much loved academic theories about productivity improvement, learned during his MBA.

Because of Empathy’s seven-year history with BG and previous delivery of valuable ethnographic research, the client put their trust in Empathy’s recommendation. The client accepted Empathy’s focus and approach and set a budget.

But the Empathy team was nervous. Given the strong macro forces encountered by small businesses in New Zealand, was there really anything that we could do to help small businesses beyond what the client had originally intended? If Empathy didn’t find anything useful in their ethnographic study, BG would have spent time and money only to find themselves back at their original, untested ideas for interventions. Further, they would lose credibility with wider government.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Decision Crossroads

BG set a budget for the research and recommendations. The budget was not large. That, combined with the prevailing focus on macro forces, brought forth a number of decision crossroads for Empathy. Most notably:

- Should the research involve a larger number of businesses, or focus on fewer businesses?

- Should the research involve only the small business owners and operators, or also the workers?

- Should the research specifically seek to identify macro forces and mitigations at play at the business level, or politely ignore the prevailing thinking to take a genuinely fresh look?

Deep or Wide

Should the research involve a larger number of businesses, or focus on fewer businesses?

With a limited budget, researchers often face this decision crossroad. The chosen path is often influenced by what is best for the quality of the research, and what is going to be most impactful for those who must accept the research outcomes.

Empathy knew that the wider government stakeholders of this research already felt tentative about the approach. Further, big data tends to influence those stakeholders more than ethnographic research. Government officials are often criticised for their decisions, and numbers help to give strength of evidence and foster courage of conviction.

Those considerations pointed Empathy towards working with more participants. Reporting that Empathy researched 30 businesses would make the findings more compelling than reporting that they researched five.

Also relevant was the need to consider representation of different business characteristics. Geographic location, industry type, number of employees and business entity type might all be factors influencing productivity. Empathy would need to involve more businesses to represent each of those characteristics.

On the flip side, shallow research across many companies would not be quality research, and could easily and fairly be discredited. Empathy knew that they would need more than an hour with each business to gain any sort of contextual understanding. They wanted to understand the business from more than one point of view — using more than one research technique, and /or seeing the business through the eyes of more than one person.

Empathy also realised that they could narrow the distribution of businesses. They decided that, while rural businesses might have different behaviours and mindsets around productivity, the vast majority of small businesses are in urban centres. Further, earlier ethnographic research suggested that small businesses do not differ markedly between different urban centres. Although that research did not look specifically at productivity differences, Empathy and the client decided that urban spread was not critical. Finally, the team decided the businesses’ legal profile was not likely to affect productivity in New Zealand.

The two characteristics that seemed most important to capture were number of employees and industry. Given the budget, Empathy would not be able to draw conclusions about different businesses in industries or with different numbers of employees. For example, Empathy would not be able to determine which industry or team size macro-level forces impacted the most, or which were most likely to employ successful strategies. But including a mix of industries and team sizes seemed a sensible way of mitigating criticism that the findings were not indicative of all small businesses.

As always, Empathy considered what was going to lead to the best quality research, and what was going to increase the likelihood of acceptance. Although a larger number of participants would increase the findings’ credibility, each participant business would be engaged superficially. Empathy deemed the negative impact on research quality too great. Besides, fundamentally Empathy is opposed to taking a pseudo-quantitative approach. Qualitative ethnography should stand on its own research merits, not make out like it is providing statistically significant data.

They opted for deeper engagements with a five participant businesses, and ensured a mix of industries and team sizes.

Owners and/or Workers

Should the research involve only the small business owners and operators, or also the workers?

Empathy knew that BG exists to support and influence small business owners and operators. Further, wider government believed that owners and operators are in the key position to push and pull productivity levers. In that way, it might seem better to focus limited field time on owners and operators, as that is where government believed it could have the most impact.

On the other hand, only looking at the bosses in an organisation leads to seeing the productivity of the business from only one angle. The workers may have a different view of productivity — different mindset, different behaviours, different motivations — and that different perspective might lessen the impact of the owners’ or operators’ approach.

Empathy’s view was that, in order to create appropriate interventions, they needed to understand the topic of productivity in a small business from different viewpoints within the business. By understanding productivity from the employers’ and the workers’ points of view, Empathy could see small business productivity more holistically and more genuinely. Empathy chose to involve both the owners /operators and the workers of the participating small businesses.

Ignore or Observe Macro Forces

Should the research specifically seek to identify macro forces and mitigations at play at the business level, or politely ignore the prevailing thinking to take a genuinely fresh look?

It was clear to Empathy that wider government believed that addressing macro-level forces was critical in a small businesses’ productivity. The suggestion from wider government and BG was that macro-level causes of productivity could be identified at a business level, and corresponding business-level interventions created.

In an early project document outlining the “current view of relevant research and professional literature,” BG had highlighted some areas of productivity that Empathy might like to observe in the field, based on macro-level forces.

The knowledge shared in this document will enable Empathy’s field observations to be associated to the relevant firm level and macro problems. If we can categorise the observations like this, it will be beneficial, as the solutions to address macro problems are well documented. Ideally, these collective understandings will help BG to enable businesses to adopt more productive practices.

However, later in that document, BG was careful to note:

If some of these questions don’t align with the project brief, please don’t change your approach to this project significantly based on the questions below. Again, they are just a way for BG to illustrate current knowledge, and lack of, we don’t expect field findings to cover all these questions specifically.

Further, Empathy and BG had subsequently agreed that Empathy would take an ethnographic approach that provided an understanding of productivity from the small businesses’ point of view.

Empathy had agreement in principle to step away from the prevailing approach of wider government and academic theories of productivity. But Empathy also knew that the agreement for this approach was tentative. The client was skeptical that the approach would result in actionable insights, and were proceeding on good faith underpinned by relationship history. Further, Empathy and BG would still have to ‘sell’ the research findings and intervention recommendations to wider government, who were focused on macro-level forces.

Additionally, Empathy was nervous that, given wider government’s prevailing belief that strong macro forces negatively affect small businesses in New Zealand, recommendations might be limited to the kind of interventions associated with macro forces that BG had already imagined. The research team wondered if seeking observations that could be associated directly to macro forces would help to reduce risk of the ethnography surfacing no actionable insights.

On the other hand, the Empathy researchers worried that specifically seeking observations that could be tagged in that way would distract them from gathering information that would enable a true and holistic understanding of productivity in the small business. Worse, it might make them assign more importance to observations than warranted given the businesses’ point of view.

In that way, rather than providing a safety net for the research, mindfully seeking instances or absences of actions related to macro forces could negatively impact the research.

Empathy decided to remove the possible safety net, and have faith in the research approach that they had advocated for so strongly. As the Empathy project lead declared at the time, Empathy decided to “trust the power of agenda-less ethnography.” If macro forces came up in the field, Empathy captured them. But they didn’t go looking for macro forces at play.

Research Activities

In preparing for the field, Empathy tried to understand the field of productivity a little more, before putting that learning to the back of mind. They conducted desk research and spoke with government productivity experts to learn what topic areas to consider when observing and conversing with owners and employees. Empathy also spoke with a government-approved advisor to small businesses to gain another perspective on the context of small business productivity. They wanted to understand what advisors were telling small businesses when it comes to productivity. Are they telling them it is a good thing? How are they communicating benefits? What methods are advisors recommending for productive environments? The advisor also provided the researchers with an understanding of the language used when he spoke about productivity with his small business clients. How was he defining it?

Although Empathy only spoke to one advisor, it helped Empathy frame their research conversations and provided a little more context. Empathy obtained a good indication of what one government-trusted advisor sees in the many businesses he advises. In that way, speaking to the advisor helped the client to feel better about Empathy ‘only’ engaging with five small businesses.

Empathy conducted field research with five small businesses. The businesses came from different industries — agriculture, production, professional services, retail, and food and beverage — and had between 0 and 20 employees. Within each business, a single researcher conducted multiple activities over the course of a single day.

Observations – One Empathy researcher observed each business for two hours. The observations primarily occurred without any conversation, but included some moments of participation. In a few of the small businesses, Empathy was able to understand processes more fully by being a part of them.

Observations gave Empathy an opportunity to:

- experience the productivity mindsets of the small business

- witness systems, processes and tools as they relate to productivity, eg those that increase/decrease staff engagement, those that help staff to understand their tasks and schedules, those that add/remove idle time

- observe the interpersonal relationships between co-workers, and between employers and their employees

- pick up on context before delving deep into conversation.

Conversations – One Empathy researcher conducted semi-structured conversations within each business. In total, they conducted 12 conversations with operators and employees. Each conversation lasted about an hour.

Conversations gave Empathy an opportunity to learn about:

- mindsets on productivity

- barriers to productivity

- motivations for productivity

- desires to learn about productivity

- what activities small business owners and employees are doing when they consider themselves to be ‘working on the business’ or ‘being productive’.

Three Empathy researchers undertook the fieldwork. One engaged with one business, two engaged with two small businesses each. Empathy created observation guides and conversation guides to use in the field.

Field guides

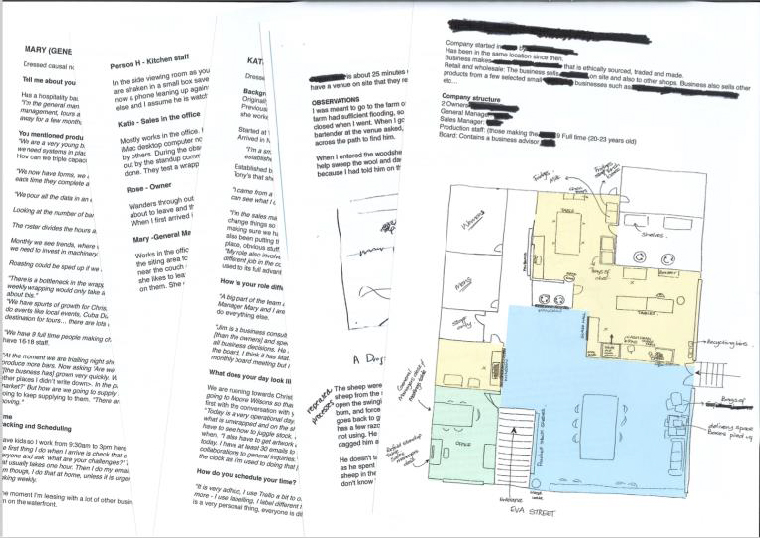

A photo from the field

Field reports

The Empathy lead was prescriptive about what each researcher should include in the field notes and subsequent field reports. In this project, the three researchers varied in background and research experience. The project lead recognised that some researchers might lack structure in their approach. She wanted to create a checklist of things for each researcher to collect, so that each brought the same types of information back from the field and into the analysis phase. Before the fieldwork occurred, she set and communicated the structure of the field reports. In that way, the report structure supported the researchers in the field alongside the observation guide and conversation guides.

During the fieldwork, each researcher took notes and made drawings. Field notes included:

- chronological shorthand — this happened, then this happened…

- sketches/maps of the environment

- networks/maps of movement

- storyboards of activities

- photos of space.

Later, the researchers turned their notes into field reports. The field report for each business included:

- narrative descriptions of the observation

- diagrams or pictures of the environment from the observation

- collateral material gathered from the business, eg policies, procedures

- whole passages of direct quotes from conversations with those in situ

- additional observation data from conversations—body language, noticed reactions, etc.

Each field report was five to 10 pages long.

Field reports

ANALYSIS OF RESEARCH FINDINGS, DEFINITION OF MEANING

Analysis Approach

Each researcher received printed copies of the field reports of each small business. They spent time reading silently, highlighting passages of particular interest in the reports, noting questions for the researcher, and capturing questions and thoughts that arose for analysis.

Highlighted field reports

The process was leisurely, allowing the researchers to follow thoughts sparked by field reports. The phase lasted three days, with each researcher dedicating significant blocks of time to analysis through that period.

As well as reading the field reports, this solo time meant the researchers were each able to draw some initial thoughts from the combined fieldwork without being influenced by the thinking of others. This is not typical at Empathy, where extroverts prefer to share field notes verbally and immediately bounce thoughts and ideas off each other, forming analysis and conclusions as a group. Even in a mixed introvert/extrovert team, the extroverts’ way usually wins out.

The three Empathy researchers then decided to decamp from the Empathy studio. Even though they had blocked out solo working time as they went through the field reports, the studio environment and other conversations proved distracting. They knew they would do better analysis away from the bustle and interruptions of the studio. They set up around the dining table in the home of one team-member.

Home set-up during analysis

That environment fostered casual conversation about the findings, which in turn, stimulated input and collaboration. The environment also reduced distractions and interruptions.

The researchers began by sharing some of the questions and thoughts that had arisen for each of them during their solo time. The team found it interesting to see which thoughts had arisen for all of them, although those thoughts were not prioritised or given more weight than ones raised by only one researcher.

The researchers devoted several hours to straight discussion. They did not intend to come up with any insights immediately. They wanted to set out time specifically just to move from solo thought to group discussion. They intended this phase of group discussion only to answer questions and to help each individual researcher refine their own thinking through group presentation.

This was helpful in that the researchers had to start explaining themselves, and therefore clarify their own thoughts, before coming up with insights and conclusions together. As this discussion was occurring, each individual researcher continued taking their own notes about questions arising and conclusions drawn. In that way, the researchers let the conversation evolve, and revisited points they wished to explore further.

Finally, it was time to translate individual thoughts into patterns and initial insights. This also took the form of discussion. However, the goal during this session was to expand their thinking into as many patterns and initial insights as the team could develop. Next, they focused on the main patterns and insights. They put those aside after completing the focus.

Research Findings

In light of the original focus of BG and wider government, the findings were interesting. Specific findings are confidential and the intellectual property of BG. However, we discuss what Empathy found relating to the prevailing view of wider government, and how these findings shifted BG’s perspective.

Empathy were able to explain how small businesses defined productivity. Wider government suggests that productivity is how efficiently an organisation can turn its inputs, such as labour and capital, into outputs in the form of goods and services. That is, the amount of output (products, services) a business can produce given its resources. In contrast, small businesses define productivity simply as the amount of work they can do. One small business owner explained that he feels productive “if I can get through my to-do list.”

The amount of resource spent to create the output is a key feature of the government’s definition. It is notably absent in small businesses’ point of view. Small businesses considered output, but not in comparison to input. This wasn’t simply about discounting family or personal labour. In fact, the small business did not discount labour, or no more than in a larger business. Rather, Empathy found this was a fundamental difference in the definition of productivity. Government thinks of rates, small businesses think of amounts.

Empathy showed how the small businesses approached productivity — by both their own and wider government’s definition. Empathy showed what approaches and actions they took, when and why. Importantly, very few of these actions related to the macro forces BG so strongly noted. Rather, actions were grounded in low-level everyday activities that ensure business survival, such as fulfilling an order on time given the people working on the shift.

Empathy found that it was not macro forces standing in the way of small business productivity. Rather, owner / operator practices are responsible. The owner / operator prioritised speed over efficiency and immediate results over long-term benefits. Put another way, urgency won over importance.

That focus on urgent tasks over important tasks perhaps is not surprising, given that small business owners / operators are often busy and understaffed, and therefore reactive. Further, many small business owners have the skills and experience to do the job. They find it easier to just do it themselves, rather than to train or explain it to someone else, and are happier with the quality and outcome. This finding was important given the government’s initial focus on macro forces. It meant small businesses could significantly improve their productivity through improvements in basic management, leadership, workforce planning and processes unrelated to macro forces.

Empathy did find some macro forces at play in the small businesses they researched. But small business did not experience these forces in the way BG imagined. Small businesses were aware of some macro forces. However, either they did not perceive those forces as a problem, or did not believe they could do anything about them.

For example, government views a lack of competition as a barrier to improving productivity. They want more competition and behaviour that is more competitive. However, the small businesses Empathy researched like that they have few direct competitors, and enjoy thinking of their indirect competitors as friends with whom they can bond and learn. Some also think of direct competitors as collaborators or at least friends. As one owner said: “We’re a community. It’s good to talk to people in your industry. We’re competitors, but we don’t see it that way.” Some owners seemed proud of this situation, as they believe it reduces stress for themselves and their employees.

This way of seeing competitors is not necessarily wrong or counter to business success. Empathy knew from previous work with other areas of government that many recognise the value of strategic collaborations within industries and within supply chains. However, for this project Empathy’s clients and stakeholders saw competition as a force that spurs businesses to do better with the resources they have. These stakeholders lamented the lack of competition, saw it as productivity reducing, and wanted to know what small businesses were doing about it. Finding that small businesses are unconcerned by the lack of direct competition, and co-exist with indirect competition, meant that BG did not have a ripe audience for wider government’s intended messages.

Perhaps most importantly, Empathy found that small businesses were not particularly interested in increasing productivity — at least, not in the way the government hoped. The government wants businesses to increase their output in a way that minimises input. Ultimately, government wants increased productivity to lead to increased GDP (gross domestic product). They want the country to earn more from the resources used, so the boosted economy can drive better social outcomes. However, the small businesses motivation is not to increase output, but rather to reduce input. As one owner said: “I don’t believe in growth for growth’s sake. There’s an expectation that bigger is better, but I’m not 100% driven by money.”

In fact, in response to Empathy researchers’ direct questions, some small business owners / operators stated that they did not want to increase productivity. They thought increasing productivity ran counter to their personal values of ensuring work-life balance and a stress-free work environment. To them, being productive means working your employees too hard. One owner noted:

I’ve never been a manager to crack the whip. I want the leisurely aspect [of the job] to be something they enjoy so they give me loyalty and are happier towards customers. The idea of being hyper-efficient is an enigma to me in some ways. I could do many things different, but can’t be bothered. I won’t stick a duster in someone’s hands.

These findings show that small business and government do not agree on the meaning of productivity. For government, productivity has positive connotations; it is about efficiency. For small businesses, it has negative connotations; it is about driving people harder to get more.

These learnings were important for BG and wider government to know. Rather than small businesses being hungry to increase productivity, government did not have a willing collaborator in their mission. Rather than small businesses not recognising macro forces working against them, small businesses welcome some of them like limited competition. Rather than being excited about finding ways to mitigate the effects of macro forces government perceives as negative, small businesses do not see the point of implementing changes given more pressing day-to-day issues. As one small business owner said during the research: “As a small shop in New Zealand, it’s not worth it trying to pretend you’re Amazon.”

Once again, Empathy found itself working to shift their client’s perspective. This time, about what productivity means to small businesses in New Zealand, and why that perspective is important. Empathy needed to consider the best way to communicate that story to their clients.

Decision Crossroad: Mindsets

Popularised by Carol Dweck (2006), ‘mindsets’ refer to the established set of attitudes and beliefs someone holds. Empathy had previously successfully delivered mindsets to BG as part of design research deliverables. Because of that success, BG requested mindsets as an output of the productivity research. Some of the Empathy team felt uneasy about the creation of mindsets on this project. One team-member suggested that mindsets often give the impression of a total set of perspectives. That is, the mindsets outlined are all of the mindsets in the population, or at least the prevailing ones. The team member argued that Empathy should only give that impression if they were confident in its truth-value.

As predominantly qualitative researchers, Empathy seldom seek to understand population variation. But their research findings are often taken to be generally applicable to the population to some degree of scale, largely because they usually involve larger number of participants, typically 20 to 60. In such cases, the project team member had more confidence that the mindsets they observed were representative of the population.

On this project, Empathy ‘only’ engaged with five small businesses. Was it right to suggest a set of mindsets exist across New Zealand small businesses as a result? Was it even possible to identify mindsets from such a small sample?

In the project, this moment was less of a decision crossroad than it perhaps should have been. BG asked for mindsets. Empathy felt uneasy but entertained the idea. As they worked through the analysis and definition phase, Empathy began to see some useful mindsets emerge. By the end, they felt comfortable with the idea of pulling out summary mindsets. And so, that is what they delivered.

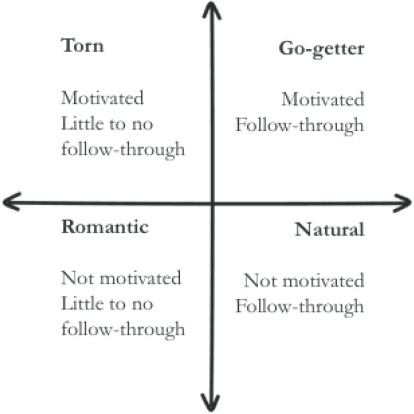

Empathy took an inductive reasoning approach. They did this by looking at their data set and determining similarities and differences throughout. They came up with qualities and key language that varied between the businesses and began to group them. Four mindsets emerged, sitting on a two-by-two. That is, the interaction of two axis, giving rise to four quadrants. Naming each mindset was the final step. Naming at the end of the process was important, as the qualities of the mindsets needed to become apparent before their classification. It allowed the team to consider what the mindset was before labelling the mindset or those with the mindset. As consultants, Empathy recognises the value of analogies to underpin mindsets. In this case, Empathy referenced the types of students many remember from high school to label the mindsets.

Sharing Work-in-Progress with the Client

Empathy always shares initial findings and meaning with clients. They do so at a point when the insights are becoming clear and the direction of recommendations are forming. Sharing at this point allows clients to learn from the research, ask questions that researchers can then reflect on, and provide input into recommendations to ensure they suit the clients’ organisation and goals.

For the researchers, sharing with the client felt like a big moment. Empathy knew BG trusted them to decide a research approach, but that they were also skeptical of a move away from a focus on macro forces.

Empathy shared some of their work in progress in their typical low-fidelity way, with a Post-it note presentation in their studio. The BG project champion attended along with one colleague.

Empathy decided to tackle the different definitions of productivity up-front, followed by a few less confrontational findings. They then introduced the small business participants’ feelings about the macro forces as highlighted by wider government. Finally, Empathy introduced the mindsets and provided actionable insights. Throughout, Empathy quoted participants from the fieldwork.

Through the informal presentation, a few tense moments unfolded where the BG project champion probed small businesses’ definition of productivity and thoughts about macro forces. He was surprised by small businesses definition of productivity, and it took some discussion for him to understand it. Similarly, he did not immediately grasp how small business could think so differently from government about macro forces.

However, the mindsets won him over. The analogy was easy to grasp, and helped to outline the ways small businesses think about productivity. The mindsets steered the client away from a discussion of macro forces, and helped him to shift his perspective from the way wider government and business academia think about productivity. Interestingly, once the client had grasped the mindsets, he seemed far more able to understand and take on board the individual findings. They anchored his thinking.

In that way, the mindsets proved critical in the success of the project. Because the mindsets captured the varying degrees to which small businesses are attracted to increased productivity, from anti to pro but unequipped, the mindsets made it clear that no small businesses thought about productivity in the way that wider government hoped and assumed. The mindsets made it clear that the macro forces that wider government had focused on, which was entirely appropriate when working on the frameworks and policies that government can influence, did not transfer to interventions implemented by small businesses.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE CREATION OF TOOLS AND RESOURCES

Buoyed on by the success of the work-in-progress presentation and discussion, Empathy progressed to establish recommendations for the BG product.

BG’s original intention was to raise awareness of macro level forces, and to suggest meso-level ways to overcome those forces. That is, policies, procedures, rules and guidelines that directly relate to macro level forces. Empathy’s research showed that raising awareness of the macro forces would not significantly change small business owners’ mindset or behaviours. Further, Empathy’s research showed that the meso-level interventions BG proposed were too sophisticated for the majority of small businesses. For example, targeting employees from a global innovation frontier in medicine, such as Boston USA, was not an effect approach to new technology adoption.

Instead, Empathy suggested more accessible meso-level mitigations and some micro-level aids, not directly related to macro forces. In general, these related to:

- Shifting misconceptions about productivity, by showing small business that productivity practices aren’t counter to human values, but rather a means to realise them — ‘be more efficient so you don’t work people so hard’.

- Engaging owners looking for quick-fix reactive solutions to issues where they have been inefficient in the past, and guiding them to a more proactive approach — eg ensuring a new member of staff understands standard operating procedures before being left to get on with the job.

- Supporting those who are interested in productivity but are not yet knowledgeable or equipped. Providing guidance, best practices, tools and hands-on activities in key areas that impact productivity regardless of their link to macro forces. Being their guide as they explore and hone practices that work.

Specific recommendations included an online assessment, online course, worksheets, templates, and educational content. Empathy also made clear recommendations about language and tone to use when talking to small businesses about productivity. For example, taking into account that productivity is a dirty word for many small businesses.

EPILOGUE: PROJECT OUTCOMES

Product Developments

Since Empathy developed the outputs of the research, Empathy has supported BG to:

- share and engage wider government in the findings and their implications

- prioritise which area of productivity to tackle first (management and leadership)

- develop some tools that help small business owners self-assess their management and leadership practice

- create worksheets that take small business owners through tasks related to management and leadership

- create content that helps to engage small business owners in management and leadership practises that improve staff happiness and business outcomes

- develop tools and content for a second productivity topic — strategic finance.

BG is investing a significant portion of its budget into resources in productivity tools and content.

A Changed Perspective

Empathy’s ethnographic approach helped BG to understand that small businesses define productivity differently than wider government. Further, the research highlighted that some small business owners are actively against increasing productivity. These two things were mind-blowing to some in wider government, and completely shifted their perspective.

BG realised they had to start the conversation about productivity with small businesses differently. They first had to get many engaged with and positive about the idea of increasing productivity. That would involve gently changing the small business definition of productivity, amongst other things. They also had an opportunity to introduce interventions that actually help productivity obliquely, by coupling them with things the small business wants to tackle. That is, by hiding the medicine in a large spoonful of honey.

The research helped wider government to realise that the macro-level focus that is so appropriate for government cannot be directly translated to interventions for small businesses. Wider government realised that they could do more at the small business level, rather than just at the macro level. While some of the findings left them feeling dismayed and deflated, they were pleased to learn of opportunities for BG to help.

Strengthened Positions

Empathy’s work helped their client to strengthen their position as a team who knows a lot about a critical group within New Zealand’s economy — small businesses. As BG’s base of knowledge about their core customer grows, they become more of a go-to source within government. This project, where they showed that a different understanding was required and where the results really shifted people’s perspectives, further cemented their role as ‘the knowers of small businesses’. Similarly, results enhanced the profile of BG as a creator of resources and interventions that respond so well to latent needs and contexts of small businesses. In the eyes of both BG and wider government, the results strengthened Empathy’s position in the same ways. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, BG is no longer skeptical of Empathy’s narrow-but-deep research approach. Whereas previously they questioned small sample sizes, Empathy encountered no negative reaction to the five-business sample used in the productivity research. The test will come when a new research project is scoped.

REFLECTIONS FOR EMPATHY

The Use of Mindsets

As mentioned earlier, Empathy initially felt uneasy about the creation of mindsets from the field research, but delivered them in the end. There was no critical analysis of whether it was right to concoct mindsets from five engagements. The researchers were swept along. In discussing this case study, this is one of the areas where Empathy wonder if they did the right thing.

The client really latched onto and placed faith in the mindsets. This was probably partly because of the catchy nature of the mindsets delivered, mindsets delivered on an earlier project that lead to an incredibly successful outcome, the strength of relationship history, and the research confidence and story-telling prowess of the current project team.

In that way, the use of mindsets on this project helped the client to grasp the findings and make the necessary shift in perspective. Further, they were undoubtedly useful in the shaping of recommendations, tools and resources. In fact, all of the subsequent effort has been driven by the mindsets. The project lead and champion at BG has repeatedly expressed appreciation of the mindsets. He even sent the Empathy lead an email seven months after delivery, saying he had been re-reading the delivered report and using the mindsets and was reminded that “it’s all so good!”

But were the mindsets valid as mindsets, or were they simply case studies or participant profiles? Each of the mindsets represented one business from the fieldwork, with the fifth business being a mid-ground between two. What if the five businesses engaged with, or even two of them, are extreme anomalies in the population? That would put all of the subsequent effort — tool design, content design, influencing of intervention — into question.

Empathy are comforted by the fact that this productivity research is just one of their many ethnographies into New Zealand small businesses over the last seven years. In that way, the observations are based in a much larger base of context.

Empathy is likely to reflect further on whether mindsets suggest broad population representation, and if so, when the use of mindsets is valid. Empathy find mindsets a very good tool for client delivery, and for the design of products, services, policies and experiences. They will continue to use them where appropriate.

A Cultural Basis

Empathy provided 10 key findings from the research, almost pitched as insights. They also provided four mindsets. From there, they moved straight into recommendations for interventions, tools and resources.

In documentation and initial delivery presentations, they did not discuss the cultural basis of those findings or mindsets. However, the culture of New Zealand businesses makes a lot of the findings almost obvious in hindsight. As Empathy presented the findings, they often found themselves saying things like: “That makes sense, given the way New Zealanders…”

Empathy wonders if it would have been good to discuss cultural underpinnings of the findings as part of their delivery. These underpinnings were discussed within the team during the analysis and definition phase, in an offhand way. But the team didn’t deeply discuss them or consciously pull them through into the delivery of the findings.

It is interesting to ponder whether the cultural basis of the findings might have made Empathy’s results more impactful for wider government, particularly in the long term. Or, whether it would have weakened the results, as people often don’t feel that their own culture is worth narrating.

In some ways, the inclusion of cultural basis would have crowded the story in the document, and might have distracted from the important findings and mindsets.

It is also worth noting that the project budget probably didn’t allow a full exploration or description of cultural underpinnings alongside the creation of mindsets.

Ethnographic Approach

As Empathy established the research approach, they were faced with a few decision crossroads. How do they feel about those decisions now? Has this project influenced the way they’ll proceed in the future?

Research focus – Empathy argued strongly for an ethnographic approach that enabled an understanding of productivity from the small businesses’ point of view. They did not want to focus on macro-level influences.

Empathy would do this again. Hopefully always. It isn’t always easy to keep the widest possible research focus, especially when non-researching clients want to collaborate on your research brief. But Empathy believe this is worth fighting for, and will nearly always be the right thing to do for the project.

Deep or wide – Empathy opted to go narrow and deep. That is, to have deeper engagements with a smaller number of participant businesses.

Considering the project in hindsight, Empathy’s project lead commented: “I personally think it’s always right. But that’s just my style.” In that way, she always favours deep over wide and will continue to after the success of this project.

Owners and/or workers – Empathy chose to involve both the owners/operators and the workers of the participating small businesses, even though the client was focused on owners/operators.

Empathy would take this position again on this project, and on future projects. They always favour understanding a target group’s issue from the angle of all of those who contribute to the issue. It also helps to provide another lens to the target group’s handling of that issue.

Ignore or observe macro forces – Empathy decided to not specifically seek to observe macro forces at play, but to capture observations related to macro forces as they arose organically in the field.

Empathy would make this decision again on this project, and will advocate the approach in future projects. Removing the narrow focus reduces the risk of artificial results, and of missing something important in the wider context. But noting specific topics or forces at play as they arise does not get in the way of the bigger research focus.

Emma Saunders Emma is co-founder of Empathy. She has a PhD in psychology, and her background weaves together people-based research with business experience in design and innovation. Emma helps organisations to focus their solutions around the significance of human value within an economic system.

MaiLynn Stormon-Trinh MaiLynn is a writer and design researcher who balances imagination with perfectionism to explore and refine ideas. She draws on her aptitude and love for fieldwork and research to tell true stories well. MaiLynn’s work in communications for non-profits on four continents has helped hone a highly engaging and empathetic writing style.

Stephani Buckland Stephani was a research and innovation lead at Empathy. She has a Masters of science in design ethnography from the University of Dundee. Stephani is a design research specialist, whose work identifies the needs, motivations and behaviours of consumers within the context of individual cultures.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – The authors acknowledge BG and New Zealand’s progressive customer-centred public sector.

REFERENCES CITED

Dweck, Carol

2006 Mindset. New York: Random House.

MBIE

2017 Small Businesses in New Zealand: How do they compare with larger firms? MBIE, June 2017. http://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/business/business-growth-agenda/sectors-reports-series/pdf-image-library/the-small-business-sector-report-and-factsheet/small-business-factsheet-2017.pdf

Productivity Hub

2015 Cut to the chase: Understanding the productivity of New Zealand Firms.

Productivity Hub, November 2015. http://www.motu.org.nz/assets/Documents/our-work/productivity-and-innovation/firm-productivity-and-performance/CTTC-on-firm-productivity.pdf