This article shares an innovative, community-centered method for research, sensemaking, and innovation in social services that has been used by communities and agencies in six states. ‘Our Tomorrows’ is a framework for capturing real-time signals while stimulating community-based solutions to complex problems. The method includes three components that establish an ongoing feedback loop between citizens and decision makers: intensive narrative data collection with web-based tools, community sensemaking workshops, and community action labs. This article covers the principles and methodology of the approach, then walks through an example of its application and outcomes in an early childhood program. Since its inception, Our Tomorrows has leveraged distributed ethnography data tools to listen to over 10,000 voices from across the country and put the everyday experiences of individuals and families at the center of local programs, policies, and systems.

Introduction

The Center for Public Partnerships is housed within the Achievement and Assessment Institute at the University of Kansas. We are a multi-disciplinary staff of over 100 researchers, data scientists, strategic planners, and communications experts serving the broad mission of optimizing the well-being of children, youth, and families. We partner with state agencies, non-profit organizations, and community organizations to provide strategic leadership and support, research and evaluation, and data management services.

As change-makers and systems-builders, we recognize that our work is built on the foundation of daily lived experience. In 2019, we launched the Our Tomorrows project to elevate the nuance and texture of daily interactions with systems and each other and mobilize local voices as a human sensor network. Rooted in complexity theory (Snowden and Boone 2007), Our Tomorrows seeks to capture real-time signals of changing dynamics in the ways families get the social supports they need while stimulating community-based solutions to “wicked problems” (Zivkovic 2021) at all levels of our social systems. Since its inception, the Our Tomorrows project has leveraged distributed ethnography (Joshi et al. 2023) data tools (such as SenseMaker and Sprying.io) to listen to nearly 10,000 voices from across the country, putting the everyday, real experiences of individuals and families at the center of local programs, policies, and systems.

Through this important work we have witnessed real ground up change in practice. By leveraging the active sensemaking approach and distributive ethnographic practices, participants in each of the Our Tomorrows frameworks (constructed with rigorous community input) share their stories of thriving or just surviving and then make sense of those experiences in their own words and ways, gathering rich data, both on participants’ experiences and, crucially, what those experiences mean to them. Patterns from these responses and their associated stories are then returned to communities through collaborative sensemaking sessions where community participants deepen collective understanding of experiential patterns, helping generate solutions and come together over the ancestral practice of shared storytelling. In the almost ten years that we have been practicing the active sensemaking approach, we have seen individuals, families, community leaders, funders, and state representatives come together at the change making table to uncover the “unknown unknowns” and create real solutions that address the things that most impact the daily lives of citizens. Whether recognizing the cost of living in a pandemic without access to technology or reliable Internet, the barriers of providing licensed in-home childcare as a home renter or identifying the ways that current programmatic requirements exclude historically oppressed and vulnerable families, our community sensemaking approach has agitated complacent systems and uncovered needed changes that can be addressed today.

Context

We are located in Kansas and have strong partnerships and do community-based work across the state. Kansas is the second most rural state in the country. In our rural and frontier areas, we have communities struggling with aging populations, out-migration to urban areas, increasing poverty, and disinvestment. Our urban areas face ongoing challenges with housing costs and food insecurity (All In For Kansas Kids 2024). The political environment is traditionally conservative and skeptical of social services, but there is also a history of leadership on children’s issues. Kansas was the first state in the nation to establish a Children’s Cabinet in 1980, and one of few states to devote Tobacco Master Settlement dollars to services to children through the establishment of the Children’s Initiatives Fund in 1999.

We have been working as a university partner providing evaluation and strategic support to social service organizations and state agencies for 20 years. We believe strongly in the importance of good data and empirical investigation to support thoughtful decision-making, and in the urgent need to make transformational systems change to support thriving families and communities. We also have a front seat to the dynamics that prevent standard evaluation practices and contexts from supporting the radical change our current circumstances demand. Survey fatigue is real. Vulnerable populations are weary of extractive techniques without feedback loops. Individuals struggle to envision innovations that are vastly different from the status quo. Imagination to change the system is often low. It takes time to develop trust and foster imagination that leads to ideation and action, and most evaluation efforts do not make space for that time or that kind of thinking. Abductive reasoning is not common in applied settings in which conclusive reports are the norm. Provocative questions make partners uncomfortable and are outside the expectations and experience of public servants. Incorporating liberating structures and futures thinking into sensemaking texts is essential to change participant mindset to a more generative state that focuses on a markedly different future.

We are always on the lookout for opportunities to address these tensions and try new strategies to support systems change, frequently drawing on the tools provided by complexity theory and foresight methods. We began experimenting with sensemaking tools with the goal of bridging the gap between abstract understandings of how to effect change and our commitment to the knowledge and wisdom of individuals and communities and locally driven solutions.

The first project in 2015 was Lemonade for Life, a training program for home visitors and other family support professionals to understand what Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) were; to learn about their own ACES and how these might be affecting their work; and to talk about ACEs with families they serve. ACEs are stressful or traumatic events that occur before a person is 18 years of age and include abuse, neglect, household dysfunction., exposure to violence, substance use, disorder and others (Centers for Disease Control 2021). We searched for innovative evaluation techniques other than typically used quantitative surveys or qualitative interviews to better understand how individuals’ own ACEs and their understanding of them interacted with how they were building relationships with families. Several web searches and discussions led us to the Cyenfin Framework (Snowden 2007) and SenseMaker understand complex social problems. We piloted the tool with several early cohorts participating in the early phases of Lemonade for Life and found the method to be promising to understand nuances during sensemaking sessions.

In 2019, the State of Kansas received a Preschool Development Grant to conduct a needs assessment and craft a strategic plan for the early childhood system. The goal of the project was to better align across the system by putting the needs and experiences of young children and their families at the center. This focus demanded a new approach to identifying and understanding the lived experience of families with young children as they navigate their daily lives and the systems intended to serve them. Responding to this need, the grant leadership team of state agencies decided to harness the power of Our Tomorrows’ innovative Community Sensemaking Approach to map families’ lived experiences and create policies and programming adaptive to families’ needs. From a complexity perspective, the overarching goal was to developing a ‘human sensor network,’ embedding citizen feedback loops and sensemaking processes into governance, and complexity-informed intervention via portfolios of safe-to-fail probes. To do this, the Our Tomorrows project rolled out in three phases:

- An intensive story collection effort to gather experiences from families across Kansas

- Community Sensemaking Workshops to make sense of the stories and the patterns that emerged

- Community Action Labs to test out small-scale innovations designed to address identified needs of families

Methods

The Our Tomorrows Project

Our Tomorrows is a narrative-based data collection project. We primarily utilize data platforms like SenseMaker and Sprying.io which can support collection of multifaceted data in the form of open text boxes, triads, sliders, and traditional multiple-choice formats. We have also developed paper versions of the framework to facilitate story collection during in-person group settings.

Frameworks are built around open-ended prompts inviting respondents to share a short story relevant to a topic or theme. One such prompt that Our Tomorrows has fielded for many years is: “Remember a time when you felt like your family or another family you know was thriving, or just surviving. Share an experience that describes what was happening at that time in the family.” Respondents are then given a series of triads which allow them to characterize the story they just shared. Examples:

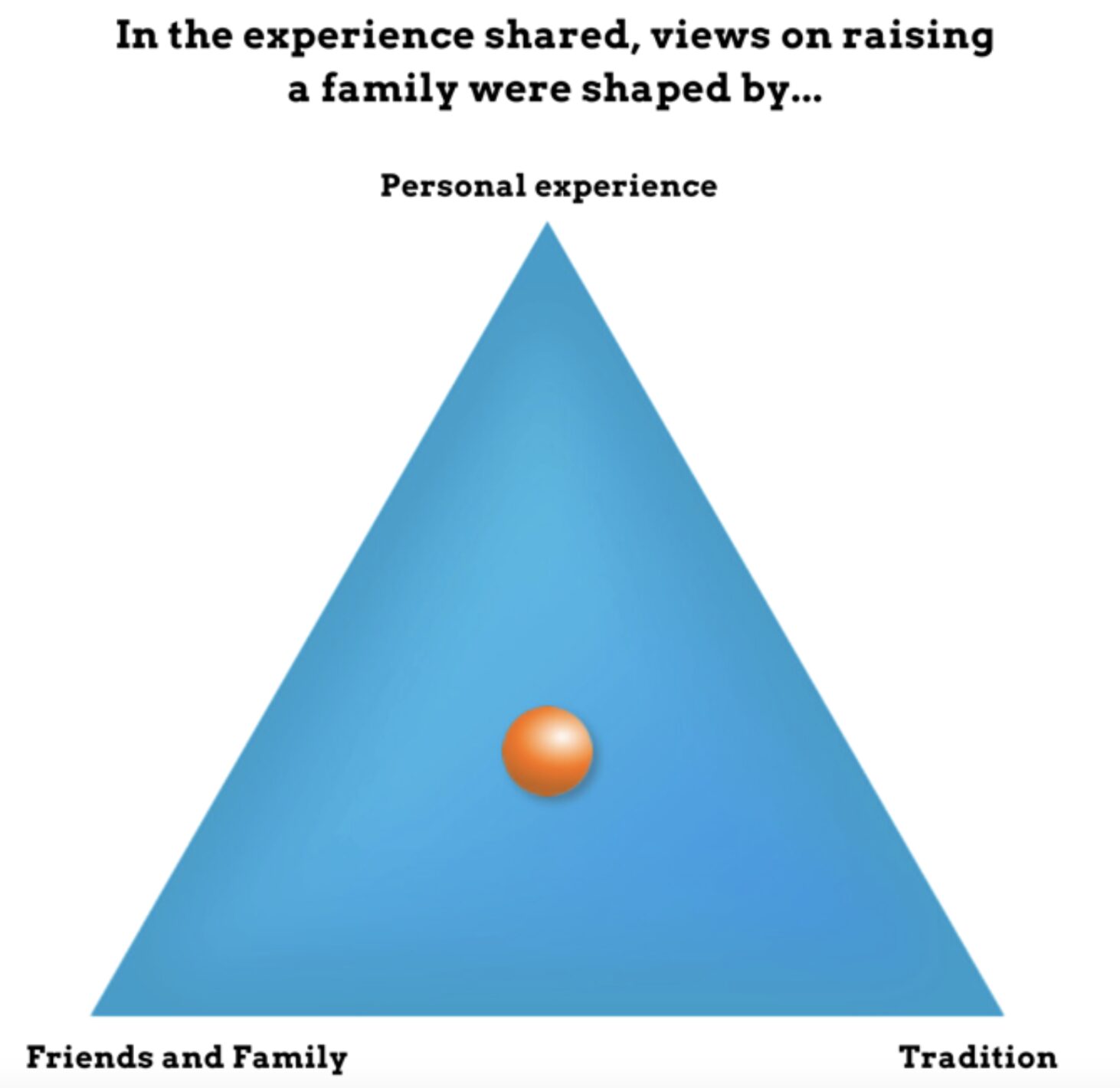

- “In the experience you shared, views on raising a family were shaped by: a) Personal experience b) Friends and family c) Tradition”;

- “In the experience you shared, who should have been responsible for making sure that kids thrived? a) The family b) Friends and community c) government.”

Respondents can code their story anywhere within a triangle, allowing them to indicate which of the three phrases apply and to what extent each is a factor, depending on the placement. Frameworks can also include more traditional survey items, providing both qualitative and quantitative data for each observation.

Image 1. Triad question from Our Tomorrows sensemaking survey, 2018. Credit: University of Kansas Center for Public Partnerships and Research.

Story Collection

State leaders, including a new Governor and leadership of the Kansas Children’s Cabinet and Trust Fund, Kansas Department of Health and Environment, Kansas Department for Children and Families, and Kansas State Department of Education, aligned to call for statewide participation in the Our Tomorrows project. With this backing, the Our Tomorrows project created a network of story collectors that contributed to a statewide story bank that decision-makers could draw on to better understand the lived experience of Kansans. Citizen Journalist Training provided organizations an understanding of the story collection method, and the Our Tomorrows team co-developed story collection strategies with each partner. Families submitted their stories online, on paper, and through interviews conducted by Citizen Journalists. This ambitious effort collected 2,279 stories from all 105 Kansas counties, capturing experiences of families in frontier, rural, and urban communities.

Analysis and Community Sensemaking

A core principle of the Our Tomorrows project is the importance of returning data to the people that shared it. Our goal is to establish a feedback loop between story sharing, sensemaking, and resulting actions. After our initial period of intensive story collection, we returned anonymous stories were then returned to communities, families, service providers, and other early childhood stakeholders at fourteen Community Sensemaking Workshops. This phase engages community members and partner organizations to uncover insights with the explicit goal of taking action.

To prepare for community sensemaking, the Our Tomorrows team conducted an initial review and analysis of the dataset. We developed the Sensemaking Analysis and Visualization Dashboard (SAVVY), which helped us identify patterns emerging from families’ experiences. Quantitative data gathered through series of triangles, sliders, a resource canvas, and multiple-choice questions provided self-signification to each narrative. When aggregated, this self-signification uncovered patterns around four themes: Bright Spots, Disruptors, Unmet Needs, and Unheard Voices.

The Our Tomorrows team developed Community Sensemaking Guides based on patterns in the data for each of the six regions in Kansas. The Guides were intended to orient participants to the project and their community’s data to enable deep conversations and prompt ideas for action. They included a description of Kansas Early Childhood Systems Building, an interpretation guide, summary data describing respondents and narratives, and initial patterns in the four thematic areas. We also compiled Story Packs for each region with groups of stories that share a similar signification in the framework. For example, a Story Pack could be all stories from a particular region where individuals selected the “Thoughtful Planning” section of a triad when characterizing how decisions were made.

The two-hour Community Sensemaking workshops were built around interpreting the Story Packs. Participants reviewed the Story Packs and sorted them into thematic categories rooted in the ways respondents interpreted their own stories, identifying emerging patterns in the conditions under which families thrive. Discussion focused on surprises, expectations, and ways to take action.

Community Action

In the final phase of the project, we launched Community Action Labs to support local initiatives that were quick, local, and inexpensive (up to $2,000). Community Action Labs created a structure for communities to test innovative ideas to address family needs as uncovered by the Our Tomorrows process, encouraging adaptive, localized strategies and a culture of experimentation to make progress on shared goals. In this spirit, we established the following principles to guide Community Action Labs:

- Big ideas start with small ripples.

- Anyone can take action and make a difference.

- Stories and families’ experiences fuel action.

- Locals know best.

- There are many paths to our shared destination.

The Our Tomorrows innovation was inspired by a partnership with the Observatory of Public Sector Innovations (OPSI) Anticipatory Innovation Governance Program and the Cynefin Centre for Applied Complexity. Our Tomorrows consulted with OPSI and the Institute for the Future on developing Community Action Labs to incorporate Facets of Innovation and futures and foresight methodologies. As a result, each Community Action Lab Actionable application was categorized along the Facets to provide insight on the disposition to innovation across the state. Our Tomorrows has laid groundwork to introduce anticipatory innovation to state decision-makers while providing avenues at the community level for immediate participation. The Cynefin Centre for Applied Complexity consists of a network of SenseMaker practitioners that have provided valuable guidance on story collection management and sensemaking workshop facilitation.

Impact

The Our Tomorrows Community Sensemaking Approach is an innovative application of complexity-informed methods toward citizen engagement in four ways:

- It is the first instance of an ongoing sensemaking feedback loop between citizens and decision-makers across an entire early childhood system.

- Every person is empowered to act according to their skillset and level of authority by asking themselves, “What can I do tomorrow to create more stories like the ones I want to see and fewer like the ones I don’t?” This “fractal engagement” puts problem-solving power in the hands of communities, not just high-level decision-makers.

- Sensemaking data is returned to communities for analysis and action planning in a comprehensible and accessible way through Community Sensemaking Workshops.

- Community Action Labs crowdsourced a portfolio of safe-to-fail experiments for complexity-informed intervention strategy through small grants.

Measuring impact from sensemaking work is challenging given the emphasis on local level community-based conversations and solutions. Thanks to the Our Tomorrows development of direct-to-community Action Labs and facilitation of community sensemaking sessions, the Center for Public Partnerships and Research has observed and documented several key areas of impact from the evolution of its active sensemaking work over the past eight years. These critical impacts include the use of sensemaking data for systems alignment and policy reform, investment in community organizations and members for safe-to-fail solutions, an increase in diverse community member participation and youth engagement, and active participation and support from state government agencies and policymakers.

The Our Tomorrows Story Bank provides a de-politicized lens for discussions about core issues that often devolve into partisan debates, like health care. By framing dialogue with stories of thriving or surviving, people across the political spectrum can think about problems from the perspective of families. Then, they can think about what they have the capacity to change. This work has prompted Kansas state agencies and early childhood stakeholders to use SenseMaker data for systems alignment, workforce development, adaptive program management, and building political will for systemic reforms. Specifically, five (5) state agencies with high-level decision-makers that are interested in complexity-informed intervention strategies, innovation, and futures methodologies.

Community members across the state participated in Community Action Labs to test innovative ideas developed through the sensemaking process, with investment in these micro-grants from the Kansas Children’s Cabinet and Trust Fund. In total, forty-six (46) individuals or organizations proposed local solutions for Community Action Labs, doubling the expected response. The Labs allowed them to safely take a risk on new ideas without jeopardizing pre-existing funding, relationships, or organizational boundaries. Overall, all stakeholders have learned to apply complexity principles and embed SenseMaker into their day-to-day operations along the way.

Finally, Our Tomorrows resulted in youth engagement and new dialogue on deep cultural issues. One citizen journalist was a 13-year-old who went door-to-door asking people to “make their community a better place” by sharing a story. Upon hearing of this effort, a state legislator unexpectedly and emotionally shared the youth’s story at a state meeting. This was a pivotal moment that led to an increased commitment from state leadership to center family experiences to inform decision-making. The youth was then invited to join a panel and share his hopes for his community and has been an inspiration for others across the state. Whether recognizing the cost of living in a pandemic without access to technology or reliable Internet, the barriers of providing licensed in-home childcare as a home renter or identifying the ways that current programmatic requirements exclude historically oppressed and vulnerable families, our community sensemaking approach has agitated complacent systems and uncovered needed changes that can be addressed today.

Lessons Learned

Challenges and Fails

The tension between meeting community partners ‘where they were’ and adopting new methods for community engagement styles was a constant challenge. Although there was universal interest in trying something new, people were unsure how to begin or were stuck in old ways of working. To address this problem, Our Tomorrows pursued the ‘adjacent possible’ by breaking down big ideas into manageable steps. Emerging goals of state leadership, feedback from community partners, and technical infrastructure challenges required abrupt pivots and creative solutions at scale without time for testing. Our Tomorrows communicated vision, principles, and introduced new vocabulary to maintain coherence and provide stability amidst this uncertainty.

Conditions for Success

Open-minded leadership and adequate infrastructure for grassroots participation were the most important conditions for success. The support of the Governor’s Office and state agency leaders resulted in a statewide commitment to the SenseMaking process that spread to elected officials, state boards, advisory groups, and advocacy organizations. With this support from the top, Our Tomorrows began an intensive partner on-boarding process to build local capacity for story collection, sensemaking, and Community Action Labs. The strong relationship with local partners created a bottom-up demand for the Community Sensemaking Approach that increased leadership’s investment in the innovation. This dialectic introduced the trust and stability to the process needed for sustainable change.

Replication

The Community Sensemaking Approach can be replicated by organizations, agencies, or governments that seek to use citizens’ experiences to drive complexity-informed change. With appropriate capacity and onboarding, ‘sensemaking’ organizations can adopt the SenseMaker tools, data visualization infrastructure, and strategy developed by Our Tomorrows to bolster community listening and social innovation. Our Tomorrows partners are replicating the approach locally by integrating community feedback loops into their day-to-day organizational practices. We have discussed a direct replication of Our Tomorrows in other states that have received federal grants to strengthen their early childhood systems. We are also exploring a social innovation platform collaboration with the Agirre Lehendakaria Center in the Basque Country (Spain) and sharing our approach with the members of the Cynefin Centre for Applied Complexity.

Lessons Learned

Implementing the Community Sensemaking Approach requires that practitioners play a leadership role to get others to join in a shared struggle to solve a complex problem. Lessons learned were:

1) People need to understand the why, how, and what of a process to feel secure enough to take an innovative risk. “Breadcrumbing” is an approach we developed to educate partners about innovative ways of doing things without overwhelming them with jargon and academic language. We introduced the ‘Why’ of the Community Sensemaking Approach. Then participants experienced the ‘How’ by completing program activities. Through guided reflection afterwards, we provided the language of the innovation to describe the ‘What.’ This staged process introduces complexity concepts in a consumable and respectful manner.

2) Survey fatigue is real. Vulnerable populations are weary of extractive techniques without feedback loops. Integrating story collection into routine activities and going to where people are is essential. Additionally, communication strategies must be adjusted based on the audience. The statewide project required that we use top-down and bottom-up approaches to establish feedback loops. In response, we developed “fractal knowledge management” techniques to share the same ideas in a variety of ways to provide coherence across the system while not overwhelming people who had less shared context.

3) The project team must use complexity techniques to deliver the project and be an exemplar for others. For example, Our Tomorrows utilized the Cynefin framework for situational assessment and as a guide to adjust our practices accordingly. We began the Community Action Lab process with a long application like a request for proposals. After some confusion from our partners, we recognized that we were approaching the application as a ‘clear’ problem rather than a complex one. We adjusted our approach to reflect the heuristics for action in the complex domain and created a three-question application to probe for unexpected ideas. By loosening constraints, the Labs achieved greater engagement. In the end, this resulted in a locally-driven innovation portfolio that was an iterative process built on trust and supportive coaching. Individuals struggle to envision innovation that are vastly different from the status quo. Imagination and change the system is often low. It takes time to develop trust and foster imagination that leads to ideation and action.

5) Abductive reasoning is not common in applied settings in which conclusive reports are the norm. Provocative questions make partners uncomfortable and are outside the expectations and experience of public servants. Funders are used to compliance models and to receiving reports with a set of (often expected) recommendations. Incorporating liberating structures and futures thinking into sensemaking texts needs is essential to change participant mindset to a more generative state that focuses on a markedly different future.

How the Project Has Evolved

Over the past six years, the Our Tomorrows team at the Center for Public Partnerships and Research at the University of Kansas has co-created and tested an adapted framework focused on child and family wellbeing instead of the more traditional “child welfare” approach to prevention work. This framework, which started with the Our Tomorrows 2.0 framework in Kansas, has been workshopped in varying ways by communities and agency groups in Washington, San Diego, Minnesota, and in currently ongoing ways by additional Kansas child wellbeing programs in Kansas. Every additional community and state partner that utilized this framework had the opportunity to review, test, and adapt it to best meet the unique local needs. This iterative approach to framework design across communities, identities, and levels of government resulted in a socially validated survey framework that is helping leaders at all levels of the child and family wellbeing system better serve all families in communities across the country and is helping to center the voices of “lived experience experts” in policy, funding, and programmatic decision-making.

Additionally, recent iterations of the active sensemaking model have led the way on the progression of action labs from micro-funded community grants to more policy-based action labs. Facilitated by the state of Minnesota’s MN StoryCollective project, policy-centered action labs bring together staff and leaders from multiple state and local agencies to discuss Minnesota’s sensemaking data and stories in order to convert their “a-ha” moments into quick action. By ensuring that action labs include the active participation of those who can make quick decisions, access funding, and change policies, Minnesota’s action lab model is using the active sensemaking approach to connect community issues to state level problem solvers for efficient, effective change.

Our active sensemaking team has recently engaged in adaptive and emergent design principles to temporally expand its narrative prompting. More specifically, a current project in partnership with another KU research center team is seeking narrative responses about both past youthful experiences and current adult situations, drawing connections between the things we learn as children to the outcomes we may experience in our careers as adults.

The CPPR team is exploring narrative prompting for the creation of future scenarios or stories—asking people to imagine possible futures in the year 2040. This approach is generating wider and more creative possibilities for our future and helping us understand the different ways people perceive of foresight planning, consider future possibilities, and balance the needs of today with the hopes of tomorrow. These innovative approaches to narrative prompting across generations and temporal states are indicative of a sea change in how we communicate with each other, understand our realities, and utilize core ethnographic and complex methods to make sense of what has happened, what is needed, and what is possible.

About the Authors

Jenny Flinders, MSed, leads research projects at the University of Kansas Center for Public Partnerships and Research, that center community voice in the policymaking process by leveraging complex sensemaking processes. She also leads indigenous community partnerships that seek to strengthen intergenerational wellbeing. She is a PhD candidate in Education Policy, currently researching how family choice discourse is leveraged for control across the education system. Contact at jflinders@ku.edu.

Jacqueline Counts, MSW, PhD., is the Director University of Kansas Center for Public Partnerships and Research. She leads a multi-disciplinary team of social workers, social scientists, psychologists, sociologists, and other creative staff to come together to create a better world. She has been principal investigator on over 50 grants. She uses a complexity lens to understand wicked social problems and applies futures and foresight methods to transform systems. Contact at jcounts@ku.edu.

Note

We are grateful to Dr. Jessica Sprague-Jones for her exceptional writing support, which greatly enhanced the clarity and coherence of our case study. Her expertise and dedication have been instrumental in shaping the dissemination of our work.

References Cited

All In for Kansas Kids. 2024. Kansas early childhood system needs assessment. Prepared by the University of Kansas Center for Public Partnerships and Research on behalf of the Kansas Children’s Cabinet and Trust Fund. https://kschildrenscabinet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Needs-Assessment-2024.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html

Joshi, Deepa, Anna Panagiotou, Meera Bisht, Upandha Udalagama, and Alexandra Schindler. 2023. “Digital Ethnography? Our Experiences in the Use of Sensemaker for Understanding Gendered Climate Vulnerabilities amongst Marginalized Agrarian Communities.” Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097196

Snowden, David J., and M. E. Boone. 2007. “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making.” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 11: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097196

Zivkovic, Sharon. 2021. “A Practitioner Tool for Developing and Measuring the Results of Interventions.” Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability 16, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.33423/jsis.v16i1.4183