*Apologies for the poor sound quality. We’re working on it and hope to have an improved version available soon.

Case Study—This case study will present how a multicultural and multidisciplinary team from EPAM Continuum, the global innovation design firm, gathered, analyzed, and presented back different forms of “evidence” to satisfy the complex set of client and customer needs for a Jordanian microfinance bank with 30 branches and 65,000 clients. The team navigated cultural and linguistic barriers as they sought to provide stakeholders and their customers the evidence they needed to confidently design a new “mobile payment service” for their microloan customers. Over the course of the engagement, the firm’s team strove not only to research, design, and prototype a new service to hand off to a local development team, but also to (1) use a combination of deliverables and in-field accompaniment to train microfinance bank staff in their process; (2) present evidence demonstrating the deep customer understanding that can result from pairing ethnographic research and human-centered design; and (3) create evidence that the firm’s process was both effective and replicable by bank staff.

“The mobile payment service will be one of the first – if not, the first – for the microfinance sector in the Middle East. As such, despite the fact that mobile penetration has reached approximately 200 percent in Jordan, clients may regard it cautiously.” (USAID/National Microfinance Bank of Jordan’s jointly-written Request for Proposal)

INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

Founded in 2006, Jordan’s National Microfinance Bank (NMB) was the third-largest microfinance bank in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan as of 2016 when they began their engagement with EPAM Continuum. NMB is a private shareholding institution that finances income-generating projects for underserved segments of society, serving 65,000 clients and 30 branches across the country with “an array of financial and non-financial products and services.”

As of the end of 2011 NMB held 12% of the market share of total microfinance clients in Jordan, behind Tamweelcom (25%) and the Microfund for Women (31%). Besides the four largest non-profit players (holding 74% market share), there are also several for-profit microfinance banks with smaller marketshares, and an increasing number of commercial banks are entering the space with their own microfinance products. (Jordanian Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2012)

The Request for Proposal (RfP) laid out the high-level vision for the engagement as follows:

A user-centered approach will be used to develop the mobile payment service. It will explore clients’ behaviors, thoughts, needs, and wants related to financial management and mobile applications. Understanding how clients manage finances and why they prefer one potential solution instead of another will guide the development of a service optimized to fit their lifestyle–which will increase the probability that they will trust, value, embrace, and adopt it.

The RfP was strongly rooted in language of human-centered design. In writing the RfP, USAID had collaborated with Felipe Cabezas, the Product Development Consultant on long-term appointment to NMB, and the person who would be EPAM Continuum’s main client contact within the bank. Cabezas’ expertise and interest in human-centered design shone through in the phrasing of the “Program Background” and “Objective” in the project’s RfP, which included numerous such phrases as “service design,” “user-friendly prototypes,” and “user interface (UI) and experience (UX),” and also stated that, “While any and all strategies are welcome to be considered, one-on-one interviews should play a central role” when describing how the field research be conducted.

BUSINESS CHALLENGE

Stakeholders

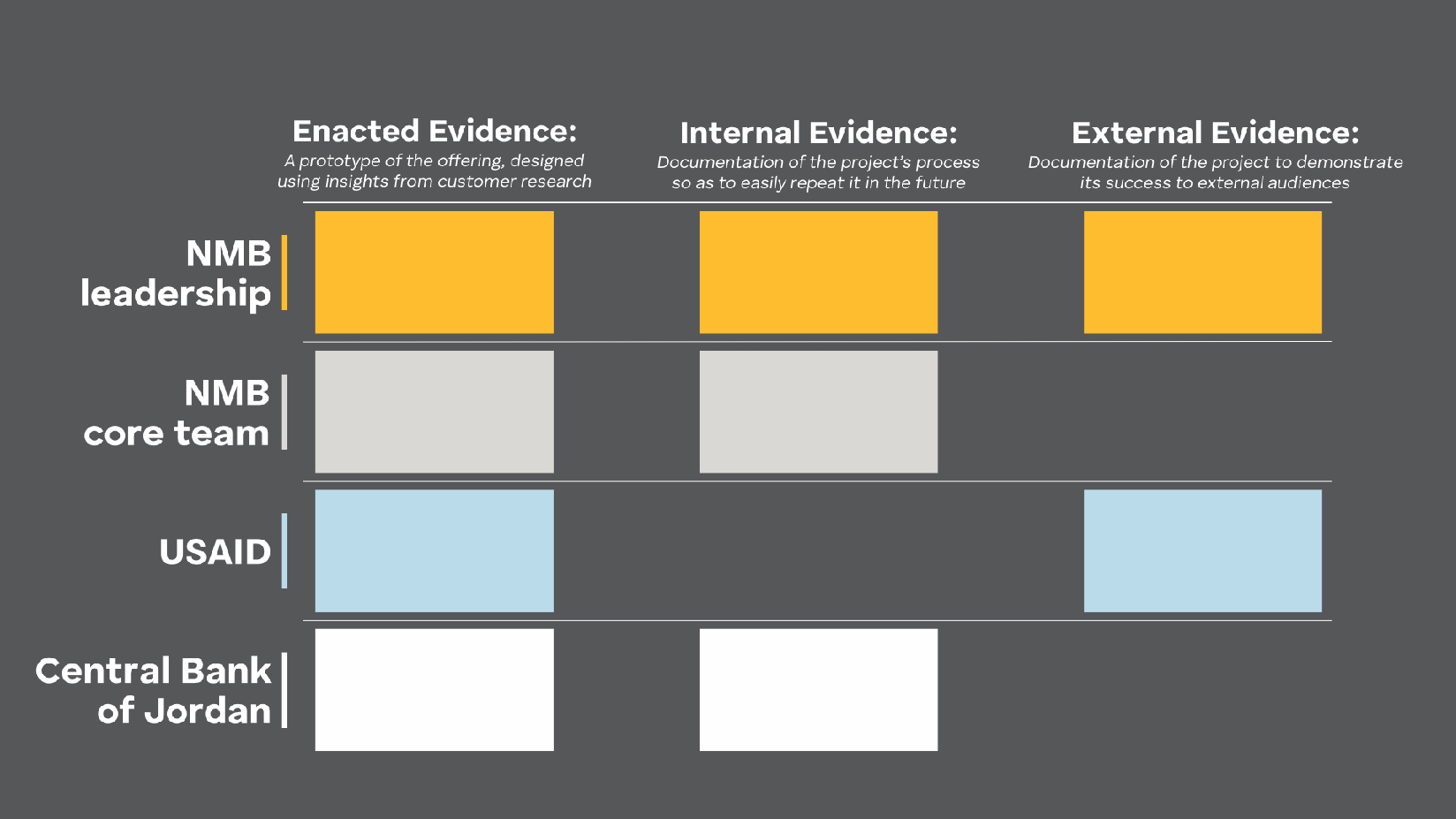

Figure 1. Visual summary of intersecting stakeholder goals. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

The novelty of an ethnographic approach to understanding people and the use of human-centered design, combined with the significant promise of the project’s result (if the aspirations laid out in the proposal were realized) meant that there was a significant amount of both interest and expectation from all of the major involved client parties, of which there were four:

First, the leadership of NMB, which included the General Manager of NMB, the Regional Manager and Head of Non-Financial Services, and the Head of IT, all wanted evidence of the bank’s customer-centricity to show the non-profit donors they worked with that they kept their customers in the forefront of their minds. To further raise the stakes, both the Regional Manager and Head of Non-Financial Services as well as the Head of IT were personally involved with the project, and saw the smooth execution of both the process and the result as partially within their responsibility. From the EPAM Continuum team’s initial meeting with him, the General Manager wanted “something that could sit on his desk” as proof that the bank had done strong, foundational work to understand what their customers wanted. Speaking broadly, these leaders wanted a successful project to yield a competitive new offering, but part and parcel with that, they were also concerned with good “optics” and positive PR for the organization.

Secondly, EPAM Continuum’s primary internal client, Felipe Cabezas, the bank’s Product Development Consultant, wanted the project to be a successful reflection of the bank’s body of work with non-profit donors (and in particular the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the main sponsor of the project). In addition to this “organizational” aspiration for the engagement, on a “personal” level, NMB’s Cabezas also wanted to further build his skills with the human-centered design process as applied to a complex business challenge.

Thirdly, the donor funding this project, USAID, was just as interested in a successful result for the project as they were in obtaining the proper sequence and collection of reports and artifacts that would enable them to prove to any external oversight committees that the services they had paid EPAM Continuum to render (problem identification, user research, designing wireframes, prototyping a service) and NMB to implement had been fully carried out. Ideally this engagement would also serve as a reflection of the good use to which their funding went, in the event USAID were to request more. At the minimum, USAID wanted proper accountability for tax and auditing standards, and this meant requiring the EPAM Continuum team to fill out and submit a variety of forms, along with examples of the work that was conducted in each project phase. In addition, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team discovered that, upon attending a meeting at USAID on the morning of their second day in the country that they were also expected to have a USAID representative accompany the team to an interview to be able to witness the ethnographic interview process firsthand.

Fourthly, the project team also experienced the somewhat unexpected addition of another critical stakeholder partway through the project: The Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ). The NMB leadership had been in touch with senior officials at the CBJ from the start of EPAM Continuum’s fieldwork, and on a day without interviews scheduled the core project team (consisting of the Head of Non-Financial Services, the Head of IT, Felipe Cabezas and the entire EPAM Continuum team) traveled to the Central Bank Building to meet with the Executive Manager for Payment Systems & Domestic Banking Operations and Financial Inclusion Department. Once there, NMB’s Head of Non-Financial Services presented the progress of the work to date, after which Stefano Bianchini, the EPAM Continuum team’s lead Service Designer and the manager of the project, shared some of the photos from fieldwork and introduced the core ideas behind human-centered design that the team had been employing to date in the project. The CBJ representative was very enthusiastic about both the goal of the project and the novel (for this context) methodology the EPAM Continuum team was using to carry out the work, and wanted to figure out how to have some of her employees gain exposure to the methods of human-centered design as it was being practiced by the project team.

Balancing and ensuring that the day-to-day activities of the project team satisfied the diverse needs of these stakeholders was a consistent point of focus for Bianchini as he tried simultaneously to protect the integrity of EPAM Continuum’s process and ensure that stakeholders all felt acknowledged.

NMB’s Past Innovations

Even before its collaboration with EPAM Continuum, NMB had a record of innovation that had set it ahead of its competitors in its ability to serve clients. When the EPAM Continuum team initially spoke with the Regional Manager/Head of Non-Financial Services and the Head of IT, they did not frame their innovations in terms of human-centered design, but rather in terms of the bank’s internal metrics, like capturing market share and processing clients’ microloan applications more quickly. The RfP highlighted a previous tech-led effort, the use of tablets by loan officers to collect loan application information from clients at their homes, instead of clients having to gather documents and travel to a branch to fill out an application. The NMB team was understandably proud that this had, as outlined in the current RfP, “decreased the application-to-disbursal period from 72 to less than 24 hours – freeing up resources to allow loan officers to serve 10 to 15 percent more clients.” In the EPAM Continuum team’s early conversations with these two NMB employees and Cabezas, NMB’s Product Development Consultant, the EPAM Continuum team encountered an unspoken tension; while the two full-time NMB employees spoke of NMB being the first microfinance banks in Jordan to employ tellers in their branches instead of making customers repay their microloans at other bank branches (an advancement that NMB’s competition soon copied), the RfP seemed to highlight NMB’s recent technology offerings as a means of obviating the need for as many human employees in favor of relying more upon technology.

Having already leveraged mobile technology to realize efficiencies around the microloan application process and broaden their client base, NMB’s leadership decided that the next natural step would be to focus on the other key part of the microloan process from the bank’s perspective: repayment. While repayment rates were satisfactory overall, the bank’s leadership wanted to understand why some microloan customers consistently repaid on time, while others (sometimes in nearly identical circumstances) struggled to do the same. Furthermore, through initial conversations, these variations in repayment rates did not appear to strongly correlate to geography or branch location, loan type, household size, or other metrics that NMB’s leadership had previously considered when deciding how to plan a new effort to improve operations. By gaining a deeper understanding of the factors that influenced how people repaid, NMB’s leadership hoped the EPAM Continuum team could design and test a solution that solved for the root causes of what prevented struggling microloan customers from repaying on time. Without a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing repayment, NMB’s fast-expanding share of the microloan market could turn from an asset into a vulnerability; too many loans to clients unable to repay could over-leverage the bank and place it in a vulnerable position.

METHODS AND INTERVIEW APPROACH

Identifying and Mapping the “NMB Microloan Journey”

In planning out the methods and stimuli for interviews, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team had to create an interview where respondents felt comfortable, so that respondents could share honestly about their past and current microloan experiences and give candid feedback on the various sketches of low-fidelity ideas the research team presented.

To familiarize themselves with the loan process, the EPAM Continuum team spoke via teleconference with the three core members of the NMB team, interviewing them in depth about all details and stages of the loan process in their eyes: how people typically discovered NMB’s services (most often word-of-mouth, or a referral from a friend or relative); the part of the loan process people complained about most (needing to provide two references on a loan application, various identifying documents, and proof of their income as shown on a bank statement); the reasons people most often provided for why they couldn’t successfully make a repayment on a given month (unanticipated expenditure wiping out money they’d saved up for their repayment); and more questions aimed at trying to uncover the “human side” of an NMB microloan without the benefit of being on the ground to discover microloan customers’ most pressing painpoints through firsthand ethnographic inquiry.

Through these interviews, the EPAM Continuum team came up with the six high-level steps that made up the loan journey:

- “I realize I need a loan”

- “I research the best options”

- “I sign up for my loan”

- “I get the money I need”

- “I make my repayments”

- “I make my final repayment”

The EPAM Continuum team consciously chose a “first-person” framing for the journey steps, because even though initially this made speaking about the steps somewhat cumbersome, it also forced both EPAM Continuum and NMB team members to acknowledge the highly personal nature of getting a loan, and the individuality of each journey.

After receiving approval and buy-in around this as a valid way to break down the microloan process from NMB stakeholders, the EPAM Continuum team adopted this as their general frame for thinking about all potential new ideas, offerings, and processes going forward.

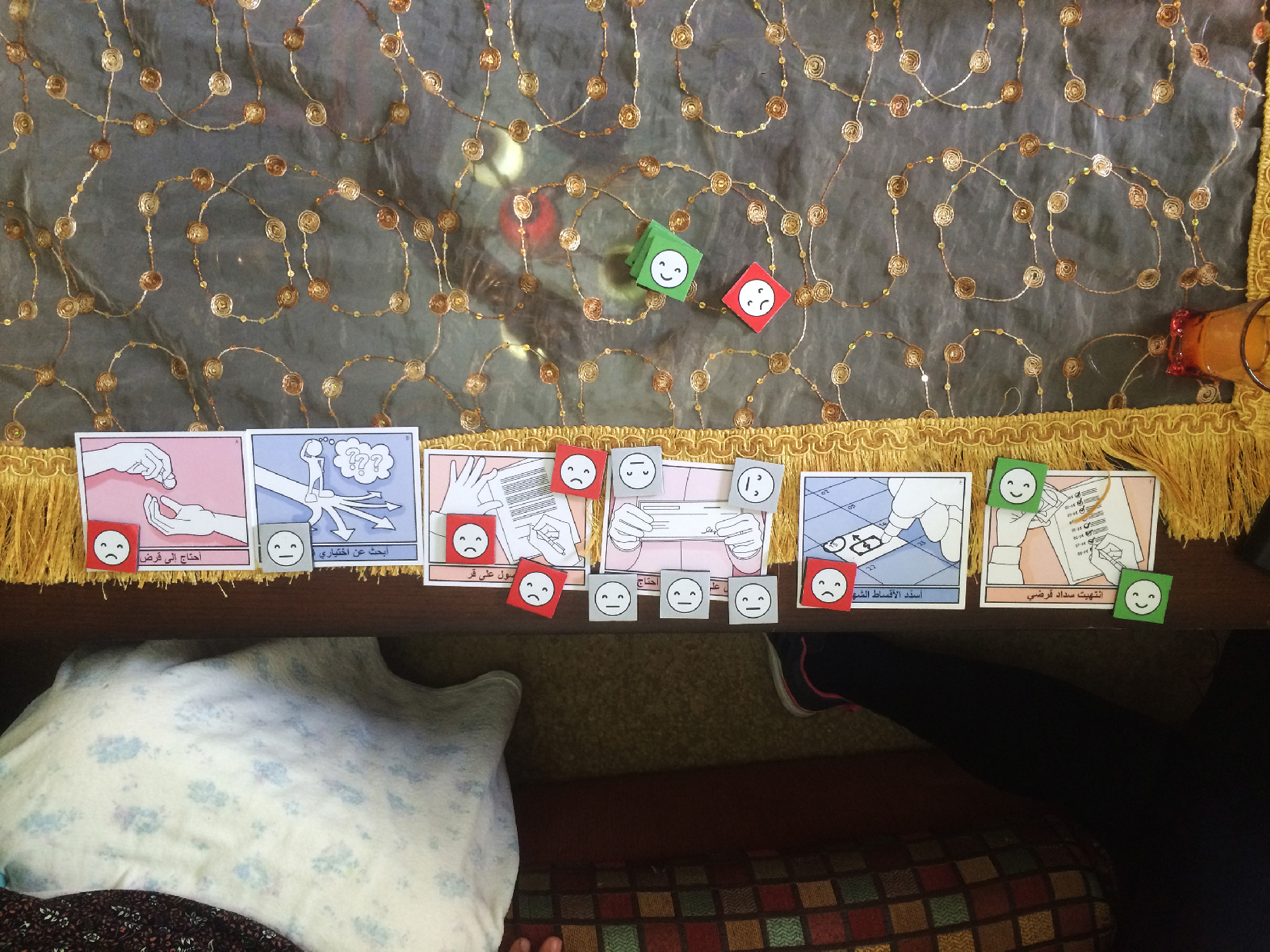

Interview Sequence

The in-depth review of each individual’s loan process became what the EPAM Continuum team placed at the beginning of each of their sixteen generative interviews, which they hoped would establish respondents’ “expertise” about their loan and make them feel more comfortable sharing their candid thoughts as the team proceeded through the remainder of the interview. After establishing rapport, the lead interviewer would present the set of six “loan journey” cards to respondents, asking them to talk through their most recently completed or current microloan and placing small, colored tiles with either happy, indifferent, or unhappy faces on them on to each of the six journey cards to create a visual record of the respondent’s feedback and thoughts around each step of their loan journey. (Sanders, 2014)

Figure 2. The six “journey step” cards, representing the major stages of an NMB microloan customer’s journey, along with tiles placed by the respondent indicating their emotions in each step. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

The research team knew that the majority of respondents would be female, and so decided that the “protagonist” of the loan journey stimuli cards that would be used to help guide respondents should also be female, since through conversations with NMB stakeholders it was revealed women were often the true controllers of the household’s finances (even if loans were often applied for in the male head of household’s name if there was one).

Once the EPAM Continuum team had settled upon the primary, high-level steps of the journey, they began placing all of the various details, painpoints, and touchpoints between the client and NMB into the journey, incorporating their “understanding from a distance” of some of clients’ challenges uncovered through discussions with NMB about the loan process beneath each of the major steps of the loan journey. After standing back to appraise this collage of quotes, client-bank contact points, and conspicuous gaps, the EPAM Continuum team began placing an additional layer of ideas on top of this foundation: loose, basic sketches of ideas that could potentially simplify or improve the client’s loan experience. Although EPAM Continuum was tasked with creating a “mobile payment service,” they did not want to lose sight of the other business goals NMB had in mind as well—serving more clients, developing desirable and competitive financial products, and becoming Jordan’s preferred microfinance institution.

EPAM Continuum categorized the ideas they generated based upon the section of the loan process they affected, and shared these with their broader group of stakeholders at NMB to collect feedback. The research team was careful to emphasize their intention of placing “early stage” sketches of ideas in front of clients, not intending to commit NMB to building the ideas customers reacted most strongly to, but rather to understand the unmet needs that made those ideas resonate with their customers.

Figure 3. Several of the “early stage” idea cards laid out on the floor of a respondent’s home for their appraisal. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

FIELD APPROACH

Stakeholder Management: Balancing Data Quality, Stakeholder Satisfaction, and Client Education

In discussions throughout the Alignment phase of the project, the EPAM Continuum and NMB teams had discussed extensively the “ideal” number of participants to bring along to an interview. While EPAM Continuum was accustomed to bringing a client along to a given respondent interview for the helpful empathy, context, and skills it could build, the team also sought to limit the number of interview attendees to make respondents more comfortable by having fewer strangers in their home.

For this engagement, a typical interview would have a separate note taker and lead interviewer from EPAM Continuum, a translator/fixer, and an employee of NMB for a total of four people attending each interview. In addition, the research team also needed to account for additional guests for certain interviews—an employee of the Central Bank of Jordan interested in learning about human-centered design, and an employee of USAID who was both interested in human-centered design and also wanted to observe interviews to be able to report back that the EPAM Continuum team had in fact delivered upon their promised process.

This made for challenges to the EPAM Continuum team’s usual process, as they struggled to balance accommodating multiple stakeholders’ representatives that they wanted to attend the interview with the need for intimacy, due to the sensitivity of the conversations that the teams would be having with NMB clients about their finances. (Taylor, 2013) From their past work, the EPAM Continuum team was distinctly aware of the potential decrease in candidness (and therefore quality of ethnographic data) that came with having more strangers in the interview environment. To get around this, the team decided to “over-recruit” and run additional in-context ethnographic interviews around the capital, Amman, (where it would be most convenient for the representatives from both USAID and the Central Bank of Jordan to attend) and be prepared to account for those interviews not yielding the same quality of data as interviews where it was only the core NMB and EPAM Continuum team members in attendance.

Recruiting and Employee Interviews

To recruit respondents for the project’s first round of generative interviews, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team worked directly with bank branch managers in the different cities and towns they planned upon visiting for research, chosen for locations with NMB branches, and to give the research team a diverse sample of different population densities (urban and rural) and geographic regions. Although the team was aware of the potential trade-offs that would come with the respondent knowing that NMB was the bank about which the team was interested in learning, the team decided that it would be too difficult for the research team’s fixer/translator, Shereen Zoumot, to reach out to a respondent independently of NMB and build the trust necessary to get invited into their homes.

To limit the bias that would be inherent if the local NMB branch employee that the respondent personally knew were in the same room during the interview, the team designed the protocol to include the moment where, after making the introduction between the research team members and the respondent, and reminding the respondent to share their honest opinions and answer the team’s questions candidly, the local NMB branch employee who arranged the interview would step out of the room. For the purposes of limiting bias, any additional NMB stakeholders from NMB’s headquarters observing the interview would not be identified as such, instead being identified either as part of EPAM Continuum’s team, or “assisting” the team in some way. The research team felt this method still allowed the respondent to share their candid thoughts about their microloan, their personal finances, and any weaknesses they saw in NMB’s current microloan experience, while also making them feel comfortable enough to speak with the research team after having been introduced by a trusted person in their social network.

Finally, to understand microloans as comprehensively as possible, the team interviewed local branch employees (typically the manager in charge of selecting and recruiting customers for the team) at each of the NMB branches that helped the researchers recruit from their customer base. Through conversations with branch employees across the country, the research team understood how the formal mechanisms of credit (background checks into whether an applicant has had past loans, whether they are currently in debt, etc.) are supplemented by less formal “secondary sources,” such as when branch employees ask multiple NMB customers with strong ties to the bank and who live in the same neighborhood as the microloan applicant various cross-referencing questions (whether they know the applicant, whether the applicant is in good standing within the community, whether they’re a gambler or owe others money, or if the applicant has a background of saving through participation in community savings clubs).

Defining the Social Protocol of an In-home Ethnographic Interview

Despite EPAM Continuum and NMB’s efforts to minimize the number of attendees in an interview, oftentimes the surprise would come from the respondents themselves, for whom there was no prior social protocol for an in-home or at-work interview. From previous work, ethnographic interview respondents often did not know how to prepare to accept a group of four or five strangers into their home, and so it often became a sort of “hosting” experience, with respondents offering drinks or snacks, and sometimes invitations to stay for a meal following an interview. Particularly for interviews in smaller urban and rural settings outside of Amman, the NMB/EPAM Continuum interview often became a “social” event involving the respondent’s fellow employees, friends, relatives, neighbors, and others. In the first such encounter, the team walked into what they were expecting to be an interview with a 40-year-old female microloan customer in the smaller northern city of Irbid, a place with a population of around 500,000 near the border with Syria. After being greeted by her husband, the team was shown into the family room, where the team was joined by the respondent, her husband, a neighbor, and, at various times, the couple’s four children, ranging in age from six- to twelve years old. Sitting in the car afterwards, Zach Hyman, a Design Strategist on the EPAM Continuum team, raised the question, “Do we think this is a problem? Having all those other people in the room [besides the respondent] during the interview?” To which NMB’s Cabezas countered, “There wasn’t much of an option in that case. We are guests in their home, after all—it’d be too rude to ask a visitor to leave.” Zoumot, the team’s fixer/translator agreed, saying: “People here don’t know what to do with this kind of an interview, so they treat it almost like a party, and imagine how you would feel if someone showed up to your party and asked to you to make your friends leave.” EPAM Continuum’s Bianchini said: “What if we have a plan in place for next time, if we feel that there are too many extra people and that the number of people is hurting the conversation quality?” The team agreed to develop a plan in case encountering a similar situation in the future, which the team ended up needing to enact several days later, in the village of Deir’Alla.

After being welcomed into the respondent’s home in Deir’Alla, that of a 48-year-old woman who ran a small convenience store adjacent to her home, the team sat down and began the interview as normal. About 30 minutes in, once word had traveled around the small neighborhood that there were visitors, a neighbor showed up bearing a silver platter brimming with steaming cups of tea ? one for each of the people in the room, plus herself ? and proceeded to join into the conversation, despite not having any prior experience with microloans or interactions with NMB. Hyman and Zoumot struggled to keep the conversation focused upon the firsthand experiences of the NMB customer as her neighbor shared various observations and anecdotes ? stories of the risks of selling things on credit to customers, or the challenges of trying to assess whether a wholesaler was taking advantage of her. Eventually the research team members made eye contact with one another, and set the previously agreed-upon plan into motion; as the lead interviewer (and ostensibly the one with control over the conversation), EPAM Continuum’s Hyman stood up and said, “Ah, I forgot something important in the car, can we take a short break so I can go out and get it?”

After Zoumot translated this, Hyman and NMB’s Cabezas walked out to the car, where Cabezas explained to Taha (the team’s NMB-appointed driver who was familiar with the roads all across Jordan, and who typically waited in the car while the team conducted interviews) that it would be a great help if he could come in and have a friendly, separate conversation with the talkative guest while Cabezas (who was a strong Arabic speaker) wrote down notes. While a slight deviation from protocol, this still managed to create a positive outcome for all parties; the guest would feel like she was having her opinion heard, and Cabezas would help advance the research by asking her questions about money and her financial life. The team’s “bonus” respondent also signed an NDA to make things feel as “official” as possible. An unforeseen positive outcome from Cabezas’ conversation with the bonus respondent was that he and Taha were able to direct and control the flow conversation with her; instead of leaving open the opportunity for her to add commentary as she liked to the research team’s conversation with the NMB client. This way, Cabezas could assemble a meaningful set of observations and takeaways through his structured conversation with the guest.

The team decided to use the spare audio recorder to capture the conversation, so that it would feel as if the separate conversation she was having with Cabezas was no less important than the conversation that the EPAM Continuum team was having with the “intended” respondent. Signing an NDA also meant that both her privacy and the integrity of the research team’s data and methods would be protected. Since the team only brought a limited amount of incentive packages along, the team was unable to give a separate incentive package to the bonus respondent.

Incentives

One element that defined the NMB/EPAM Continuum team’s ethnographic interviews and might have caused them to be interpreted as more of a “social” event was the team’s choice of interview incentive. After the EPAM Continuum team landed in Jordan and met with Zoumot, their fixer/translator, for the first time, they reviewed their intended approach to how interviews would ideally run. When Hyman asked Zoumot what she thought a reasonable amount to pay respondents would be for what would be around a two-hour conversation in their home, her response was “Oh, no — paying them cash would be considered very rude.” The team had encountered what Jan Chipchase covers in detail in The Field Study Handbook, when he begins by sharing how “sometimes non-monetary incentives are a better choice.” (Chipchase, 2017). The research team considered factors such as whether refrigeration would be available for all respondents (deciding to assume it would not be) and what sorts of products and brands would both be most desirable and would confer the most status upon the respondent as their recipient.

In assembling the box of incentives, Zoumot recommended a value of approximately $50 US equivalent as appropriate to award a respondent for their participation in the two-hour interview, and together Zoumot and the EPAM Continuum team wandered the aisles of a grocery store located nearby their neighborhood-based pop-up studio in the Jabal al-Weibdeh neighborhood of Amman. After much deliberation, the team decided to include in the box:

Figure 4. Two incentive packages for the day’s interviews. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

- almonds

- dried apricots

- three flavors of Lindt dark chocolate bars

- a jar of Nutella

- a jar of Honey

- a box of dried dates

- a bottle of organic olive oil

- a bottle of Vimto (a type of fruit cordial)

Figure 5. Contents of an incentive package. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

All of the items were non-perishable, did not require refrigeration, and conferred status through an appearance of elevated taste amongst the recipients. There were also items that would appeal to any children in the household.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Before the research team could understand what drove successful repayment, they began with a broader inquiry into how people in Jordan thought about money, technology, and any overlaps between the two. The team gained this understanding through:

- stakeholder interviews with both senior bank leadership who understood the systems of money broadly

- local level, community-based NMB branch employees who interacted with customers on a daily basis

- secondary research into both technology usage and microfinance in Jordan

- an initial round of sixteen in-depth, two-hour interviews with microloan customers of different ages and loan types/sizes, spread across five Jordanian cities and villages

The Centrality of Cash

In Jordan, cash is vastly preferred over other means of payment in respondents’ daily lives. That said, the Jordanians who the research team interviewed each acknowledged the inherent drawbacks that came with carrying cash.

“I’m used to carrying around cash, but it still worries me when I do.”—Rema, 64, F, convenience store owner

For Rema, one of the first respondents the team interviewed, when it came time in the two-hour interview to broadly discuss whether she ever imagined somehow storing money on her phone, her reaction was quick: “No, never.” The team let the answer stand, with the lead interviewer looping back to discuss it in more depth after Rema had had the chance to see some of the stimuli the team had arrived with, and that she was encouraged to indulge in the not-yet-possible. When re-asked in a similar way, Rema replied: “Yes, I could see storing money on my phone, but I would want to put it in myself, and then I would want to be able to have the cash [be dispensed directly out] of the phone whenever I wanted.”

While technically infeasible, Rema’s design requirement spoke to both her dedication to and comfort with cash, as well as her lack of trust in being able to invisibly “send” her money to someone or somewhere else using only her phone. Rather, when she needed money stored on her phone, she would have preferred to dial in the amount required and then hand the physical cash to the recipient. Whatever this sort of object might be called, one certainty was that it certainly did not behave like any wallet (or “e-wallet”) that the research team had ever heard of.

The high standards Rema held for her digital device to hypothetically function as a means of storing and safely carrying physical cash stood out to the team, and from that early interview, the research team made it a key component of subsequent interviews to explore precisely what it was about cash that made people reluctant to put it in one of the several “e-wallets” offered by Jordan’s mobile network operators.

The Importance of In-Person Interaction, and the Connection to Wastah

As the research team explored Jordanians’ preference for cash more deeply in subsequent interviews, it became clear that cash was something that, for all of its perceived risks and weaknesses, was important for bringing people together, into the same time and place, to physically exchange value (Maurer, 2013). The comfort with cash seemed to go part and parcel with people’s preference for in-person interactions with their friends and shopkeepers.

Rema, the woman who would have preferred to place money “into her phone” provided she could print it out directly from the phone at her convenience, shared with the research team how she enjoyed the act of repaying her loan in person at the bank branch. When the team probed into what she enjoyed about the journey to the local branch, both a time- and effort-consuming act for a 64-year-old woman suffering from mobility issues, she said, “they’re my friends [at the branch], and I enjoy speaking with them. It wouldn’t be the same to just use a phone [to repay a microloan].”

As the team asked subsequent respondents about this topic, they learned more about the relationships formed through the in-person interactions and exchanges of money and favors, and how they helped build what respondents referred to as wastah. Building up one’s wastah, or ‘personal connections,’ are ways that respondents make the various processes of daily life work more easily for them. For Wafa, a 39-year-old hairdresser, when referring to the local NMB branch where she made her repayments, she did not use the phrase ‘bank branch,’ instead specifically referring by name to Noor, the teller who she sought out each time she visited the bank. Each interaction contributed to building her wastah with Noor, and if there was ever a mistake or misunderstanding, “I can show up in person and yell about it!” Likewise, if Noor (or one of her friends) ever needed a last-minute haircut appointment, Wafa would go through whatever pains necessary to arrange one.

Besides cash being useful to build wastah between those people exchanging it, the physical nature of cash also helped people underscore the seriousness of what they were committing to, such as when Mohammed, a 36 year-old car mechanic from Amman, shared that while he would be open to the idea of using his phone to help repay his microloan,

“If I were ever to loan money to a friend, I wouldn’t trust using a phone to do it. I’d want to make the loan using cash, so that I could look [my friend] in the eyes as I handed them the money… [this interaction] shows it is important to both of you, that [this personal loan] is a serious matter.”—Mohammed, 36, M, mechanic

The flip side of this recurring theme of reliance on cash was an aversion to almost every other form of storing value, including debit and credit cards issued by commercial banks and phone-based “e-wallets” offered by Jordan’s three main telecom providers: Zain, Umniah, and Orange.

The main driver for the lack of trust of credit cards originated from either firsthand negative experiences or secondhand stories about banks “tricking” customers who had used such cards. Mohammed, the car mechanic from Amman, shared a story of how he used his credit card to withdraw cash multiple times from various ATM’s over the course of a day while he ran various errands. He learned at the end of that month that he’d run up significant fees on that day for reasons he did not understand, and promptly threw his credit card into the discarded motor oil-powered furnace that he used to heat his car repair shop.

To underscore the country’s reliance upon cash, while the research team was in Jordan, Amman was one of the few cities in the world where Uber was piloting allowing riders to pay a driver for a ride using cash instead of with a credit card linked to the app (as with almost everywhere else in the world). Although credit cards were technically available in Jordan, relatively few Jordanians chose to have one (compared to the 55% of Americans who are credit-card holders). (Statista.com, 2018)

The Familiarity of Community Savings Clubs

One common ‘financial product’ that had roots going back into ancient history was the ‘community savings club’. A group of typically between eight and twelve people (most often women, according to NMB/EPAM Continuum’s field research) would meet each month and all the members would pool their money to pay a set, small sum to one of the members. The group would rotate who receives each month’s total payment until all members had been a recipient of the group’s pool of multiple small payments, at which point they would decide whether to start over. For the respondents the research team interviewed, there was no interest accrued on the sum they received from the other members of the group, and the savings clubs functioned primarily as means of beating participants’ temptation to spend, and building wastah between the participants.

Multiple respondents also liked the idea of money ‘staying in the community,’ rather than going to an ‘outside’ entity like a bank (even if they trusted the bank’s employees, brand, and process). Feda, a merchant who was the head of her community savings club, when asked to compare the experience of repaying a microloan to making a payment into her community savings club, described the latter as a “reverse loan,” saying: “When I make a repayment for my savings club, I feel good because I know it will be coming back to me later. When I repay NMB, I feel sad because I know [the money] is going ‘away’ from me.”

With her savings clubs, Feda felt there was less pressure for her to invest in a productive asset that would bring financial returns, because participating in savings clubs did not incur any interest charges. Savings clubs made Feda feel more comfortable choosing to invest in non-productive assets like gold.

The Challenges of Distance

The team’s research also revealed differences between rural and urban dwellers when it came to how they actually repaid. For some rural microloan customers, the nearest bank branch might be 45 minutes away by car. If the microloan customer did not own or have easy access to a vehicle, to travel such a great distance meant either waiting on the side of the road and trying to catch a ride into town with a passing driver (while carrying the entirety of one’s loan repayment with them in cash), scheduling transportation to the bank branch (which could cost significant monetary or social capital), or giving one’s loan repayment amount and bank ID card to a (hopefully sufficiently) trustworthy friend who was headed into town and trust that they would stop to make the repayment at the bank branch on the client’s behalf.

Even for urban dwellers, who typically lived closer to the bank, making repayments at the branch could still be a costly or troublesome endeavor. For Maha, a food seller who suffered from back problems after decades of working over a stove, her lack of mobility meant she would have to take a relatively expensive 4 dinar (~US $5.50) taxi ride both to and from the bank branch each month for the times when only option was repaying in person herself. Over time, she picked up workarounds for this expense, including calling her daughter who lived nearby to come and take the repayment to the bank for her, or giving the repayment to her downstairs neighbor, who is an NMB employee, for him to carry with him to work and repay on her behalf.

ANALYSIS & SOLUTIONS

Cultural Affordances in Practice

Upon arriving back in Milan studio from Jordan to begin the analysis and sensemaking process, the research team printed out, rewrote, and delved into the thousands of discrete pieces of data that they had gathered over the dozens of hours spent in conversation and observation in people’s homes and businesses (Madsbjerg, 2014). In doing so, the team sought to understand peoples’ lives broadly, but were particularly interested in what shaped financial behavior, how that translated those behaviors and beliefs into their relationship with NMB, and how that influenced whether they repaid their microloan. Looking across all sixteen respondents’ lives, the team sought to understand the innate behaviors and motivations that drove some to consistently make their monthly repayments and not others. The research team’s goal at the end of this two-week phase was to identify strong themes that appeared across conversations and throughout the research, and then invite the core NMB team members to Milan for a several-day workshop where the EPAM Continuum team would introduce the themes and explain the observations that each was drawn from, based upon what the combined team members observed together while immersed in in-context conversations and observation across Jordan. From there, attendees would work together to transform the observed themes into actionable opportunities with which to move forward into the Envisioning and Prototyping phase.

To start, the EPAM Continuum team began by examining the relationship between respondents’ financial lives and their digital lives. All respondent households that the researchers visited owned at least one cellphone, a multifaceted object that played roles in people’s lives ranging from entertainment to communication. During each interview, the research team brought up a local mobile money service offered by the country’s largest mobile network operator, Zain, that allowed one to store money on one’s phone after having deposited it at a local Zain shop. None of the sixteen respondents interviewed had ever used the service (nor had most heard of anyone who had), and the majority of respondents dismissed such a service as either unnecessary (“I’ve already got one wallet that I carry, why do I need another in my phone?”) or risky, as respondents cited fears of losing their cellphone, or children breaking a phone as they played with it, or a child accidentally giving away all of their money (as phones were often shared household devices, as with many other countries where mobile phones were still an emerging phenomenon) (Von Bayer, 2017). Respondents vastly preferred their physical wallets (and the cash inside of it) over a phone-based “e-wallet” (a term used by Jordan’s three primary mobile networks), particularly when compared with their current money storage solutions, which included hiding money under their mattress or storing it at a trusted relative or neighbor’s home to keep it safe from immediate family members looking to spend it. The research team found that this analog approach to saving money spoke to a more familiar mental model for respondents (Young, 2011).

One strong theme that emerged across the lives of those who reliably repaid their microloans monthly was their reliance upon a common object: a hassalah (the Jordanian equivalent of a piggy bank). Whether in the form of plastic-molded orbs with a slot for money, or aluminum cans wrapped with adhesive paper covered in colorful anime cartoons, hassalah were key enablers of the most successful microloan customers’ repayments, as they helped build and enforce regimented, daily microsaving. These objects were universally recognizable, and of the four respondents the research team interviewed who ran small convenience stores, all of them sold various shapes and sizes of hassalah.

Although the phone was equally ubiquitous in Jordanians’ daily lives, its open-ended and fast-evolving role stood in sharp contrast with the static, focused utility of the hassalah. Seeing the pivotal role hassalah played in many Jordanians’ social practice of saving money, the research team considered whether and how to incorporate the hassalah into the service they were designing in the form of a “cultural affordance.” John Payne, Co-founder and Managing Director of Moment Design, coined the phrase “cultural affordance” to describe a “culturally specific, iconographic image” that connects a new offering in a market to a familiar, pre-existing set of social practices by associating the novel offering with objects and ideas that are already embedded within people’s daily lives and behaviors (Payne, 2015). Designed properly, cultural affordances ground an unfamiliar new product or service within familiar mental models.

The EPAM Continuum team believed that the hassalah, reframed as a cultural affordance within the new service, could be a powerful behavior-changing force for explaining the value of the novel new service to Jordanians. The team hoped it would link to a behavior of saving money to repay microloans, which respondents said they aspired to but found difficulty doing. The team believed that a new service which adopted the mental model of a hassalah on one’s phone would speak more meaningfully to microloan customers than that of an “e-wallet”. The team’s hope for the following Envisioning and Prototyping phase was to test whether NMB’s microloan customers would react differently to a service that worked more like a hassalah (an object designed to help people save money) rather than a wallet (an object designed to help people carry and spend money).

While the team hoped to change how NMB’s customers thought about storing money on their phones through shifting their mental model from phone as “e-wallet” to phone as “e-hassalah,” they wanted to preserve as much as possible the set of human behaviors that enabled the familiarity and centrality of wastah that was so central to many NMB customers. EPAM Continuum’s proposed service prototype sought to strike the balance between simplifying the microloan repayment process through a digital element, while at the same time letting customers continue to broaden and deepen the wastah enabled by in-person exchanges of money and generosity.

Analysis workshop: Building Credibility in the Evidence

At the Analysis workshop in Milan, attended by the larger group of senior NMB stakeholders as well as the members of the research team, the EPAM Continuum team. With the help of the NMB employees who had attended particular interviews and could speak to what they learned from the respondent, the attendees discussed notable observations and learnings that had been gathered from each individual respondent. This not only transferred the knowledge that was in the heads of those who were in the field into the heads of other attendees, but also placed the presenting attendees from NMB on a pedestal of expertise, as they were able to speak firsthand about the in-home and in-business interviews they attended, further buying both them and their NMB audience members into the human-centered design process’s “way of knowing” based upon firsthand human experience. To help with this process, NMB and EPAM Continuum team members presenting about the key takeaways of different interviews, and referred to print-outs of the interview debriefings pinned to the walls.

The EPAM Continuum team and Cabezas co-presented nine themes to the attendees from NMB, with each theme focusing upon a different observation from the field—from how microloan customers were (informally) using new digital channels like Whatsapp to gather the documents needed for a loan application and send them to NMB loan officers, to the many different informal workarounds people used to keep track of the repayments they had made to NMB and the total number of repayments remaining, to the different means people used to help themselves save each month and repay their microloans on time.

The second day began with an open-ended conversation around the nine themes, with the NMB attendees going around the table and talking about which themes they most strongly believed in, and which ones they were more skeptical of. From there, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team guided the NMB attendees through a handful of different potential offerings that could be prototyped and tested in the Envisioning and Prototyping phase, along with how the different prototyped offerings would connect to the different themes.

By connecting particular themes to the various proposed ways of prototyping offerings in the following phase, the senior NMB attendees could speak to which prototyped offerings they felt most comfortable bringing to life from an organizational capability perspective. This was critical to the EPAM Continuum team’s goal of setting the project up for the highest chance of success after their direct involvement ended. The EPAM Continuum team made the conversation around feasibility and logic for pursuing a particular prototype both open and participatory. The goal was to create an atmosphere where the various senior NMB stakeholders in attendance would feel able to ask for any support and resources necessary from colleagues or superiors to make the project a reality if they were tasked with implementing part of it. This would increase the likelihood of successfully scaling the project from a prototype to an in-market offering following the Prototyping phase. From his past experience, EPAM Continuum’s Bianchini shared that letting the stakeholders who would potentially be taking control of the project down the road voice their opinions on the prototype’s feasibility was a critical component of the project’s eventual success. By having say over what could be the beginning of a new product or service, NMB stakeholders would feel both more accountable and in greater control of the project outcome knowing they would eventually be taking responsibility for it.

At the conclusion of the workshop, the EPAM Continuum team presented attendees with copies of a full-color, printed, and bound book of all of the interview debriefings from the generative phase of research, summaries of the nine themes bubbled up from those interviews, and a collection of photographs from the field that documented the team’s process and approach. The printed book was important for the senior NMB stakeholder attendees to carry back physical evidence of both the workshop and the project to date. By creating an inherently sharable object to present to their teams, they would be the de facto experts about—and advocates for—the past and future of the work. The EPAM Continuum team felt the book would also play an important role both for NMB’s General Manager, who sought physical evidence (in the form of “something to put on [his] desk”) about NMB’s ability to listen to and design for customers. Finally, EPAM Continuum held on to several copies of the book to pass along to other key stakeholders so they could have evidence of the process they were involved in and feel more invested in the outcome, in particular the project’s partners at the Central Bank of Jordan and USAID (for whom the book would be a compelling physical piece of evidence for responsibly-spent funding).

CORE SOLUTION: E-HASSALAH

The solution the senior NMB stakeholders aligned upon with the EPAM Continuum team in the Analysis workshop was to experiment with a mixed digital/analog service that would afford two new types of flexibility to NMB’s microloan customers.

The first type of flexibility was the physical location where NMB’s microloan customers physically repaid their loans. The prototype service that NMB/EPAM Continuum wanted to test in the Envisioning phase would enable NMB customers to repay their loans at the shops of trusted local merchants in their community, rather than having to arrange costly travel to a bank branch to make their repayments.

The second type of flexibility would be how microloan customers repaid their loans. Rather than limiting clients to repaying their full repayment amount on (or before) the day their monthly repayment was due, the prototype would simulate allowing respondents to make smaller repayments at a pace similar to how they would put money into a hassalah to save it: a small amount each day. The prototyped service would enable customers to repay in whatever denominations they chose over the course of a month rather than in one lump sum (as long as their cumulative small repayments added up to be the full repayment amount).

The research team saw these two flexibilities as interdependent. Individually, they were certainly novel service features for any microfinance bank, but together, the team believed they mutually re-enforced one another to make a truly novel service that could make the lives of NMB’s microloan customers significantly easier, and make NMB’s microloan offering significantly more attractive as compared to its competitors.

At the heart of the digital component of the prototyped service, and the enabler of these two types of flexibility, was the cultural affordance of the ‘e-hassalah’ As microloan customers made multiple small repayments on their microloan over the course of the month, the sum of the repayments they had made to date for that month since the last repayment would be reflected in their e-hassalah—an in-app visualization of a hassalah accompanied by graphs showing their previous months’ successful repayment, and their progress towards repaying their full amount for this month. The team felt the e-hassalah feature would help meet the needs that multiple respondents raised throughout the initial round of generative interviews:

“If I could make smaller repayments two or three times a month, it would make me feel like repayment was in easier reach… maybe I could more easily share the burden of repayment with my parents.”—Aseel, 20, F, student

“I think if someone has repaid as many loans as I have, the bank should let you choose how you want to divide your monthly repayments up over the course of a month… paying all at once is a big burden.”—Bilal, 35, shopkeeper

ENVISIONING & PROTOTYPING: DESIGNING A SERVICE, PRESENTING EVIDENCE

Prototyping Interview Process

For the final stage of the project, Envisioning and Prototyping, the team agreed that it would be critically important to understand the proposed service from the perspective of both “users” and “providers”—in this case, both microloan customers with loans to repay, and the trusted local merchants who would be accepting those customers’ repayments. To understand about what respondents liked about the prototype and what needed to change, the team planned on recruiting for and running twelve evaluative service prototype interviews, where they would interview a total of four local merchants (two urban and two rural), and speak with two loan customers at each of the four shops.

The team started by reaching out to bank branches in a both urban and rural areas to seek out local merchants with whom the local branch had particularly close relationships. The research team first interviewed the merchants, having one of the NMB team members, Saif Al Khalili, pretend to be a microloan customer coming in to make a repayment at their store using the new service. As NMB’s Al Khalili stood on one side of the counter holding a phone that had been loaded with the “customer-facing” digital wireframes, Hyman and Zoumot would be standing on the other side of the counter next to the merchant, guiding them through the “merchant-facing” digital wireframes, as Cabezas and Bianchini supported with note-taking and video-recording. Both customer- and merchant-facing wireframes had been programmed into older-model iPhones dedicated to prototyping.

Figure 6. Prototyping components, clockwise from top left; physical paper receipt to gauge receptivity towards physical versus digital receipts, physical sign made of foamcore identifying store as an official “NMB repayment point”, paper prototype created for feature phone users, digital wireframes made displayed on a prototyping phone using InVision for smartphone users. Image © EPAM Continuum, used with permission.

After testing the prototype with each merchant and gathering feedback about what they liked and would want to change about the service, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team built enough trust and rapport with the merchant for them to be comfortable with having the team ‘take over’ their store for the several hours needed to run the set of subsequent customer interviews.

For the pair of customer interviews that followed each merchant interview, an NMB microloan customer would simulate the journey of traveling to the merchant’s store, where the interview would start with collecting feedback on the sign greeting them outside of the shop, identifying it as an NMB Microloan Repayment Point. In the initial round of generative interviews, the NMB/EPAM Continuum team asked in depth questions about what would make it easier for respondents to trust a given service, and the answer came in the form of official-looking signage or stickers that made it clear that a given store was an officially sanctioned provider of a given service.

By prototyping the service in a way that would resemble reality as closely as possible, the team understood what users liked and disliked about the service as it could appear in the future. To accomplish as life-like a prototype as possible required the analog and digital components of the service to be of equal fidelity (and credibility). The goal was to have merchants and customers believe that the service was ‘real’ enough to believe it could actually exist, but still in a form where they would feel comfortable giving suggestions and sharing candid feedback on how it could be improved.

After sharing their opinions on the several examples of official-looking signage, the microloan customer would be standing in front of the merchant’s counter inside, where they would be handed the iPhone with the customer-facing set of wireframes. From that point, the remainder of the interview would consist of Zoumot and Hyman guiding the microloan customer through the prototyped repayment process, continually collecting feedback and gauging their level of comfort with the process. Throughout the prototype interview, the “merchant” the microloan customer would be speaking with was actually Al Khalili, the NMB employee who was pretending to be another merchant working in the store and sharing the space behind the counter (sometimes a comically small amount of space) with the store’s actual proprietor. As Zoumot and Hyman helped guide the customer through the prototype’s wireframes, Al Khalili would be navigating in parallel through the merchant-facing wireframes, right down to the moment of when the microloan customer actually ‘repaid’ the loan by handing Al Khalili some play Jordanian currency that the customer had received at the start of the interview. The prototyping interview concluded with Al Khalili handing the client a mockup of a physical paper receipt that reflected the repayment that they had just made, while a digital copy of the very same receipt automatically appeared in the prototype’s screen. The final part of the microloan customer interview sought to understand from customers whether both a physical and digital receipt were necessary, and if not, why the client would be sufficiently comfortable with just one of the two.

For the backstage of this e-hassalah-centric service, the research team calculated that several times per month, a local NMB branch would dispatch an employee to a designated neighborhood in their territory to collect the money that the neighborhood’s microloan customers had repaid to the merchants in the community whose shops were certified as official repayment points. After double-checking on the amount collected back at the NMB branch, the neighborhood’s microloan customers’ balances would be updated accordingly in each of their files based upon the amount they repaid, all without microloan customers needing to travel to the branch and stand in line to repay (or trust someone else to do so on their behalf).

Final Presentation and Hand-off

Following the Envisioning phase, the EPAM Continuum team was set to make their final presentation to the leadership of NMB, as well as delegates from the Central Bank of Jordan and USAID over the course of an hour-long meeting. To most compellingly share with them the evidence around the prototype that was gathered during testing, EPAM Continuum and NMB agreed that it would be important to show both merchants and microloan customers “speaking their own truths” as evidence of how they felt about the prototype. EPAM Continuum’s Bianchini cut together a highlight reel showing both merchants and customers talking about what they admired about the prototyped service, and why they were excited to see it become a reality. To give the audience a glimpse into the mechanics of the prototype in a more approachable way than just sharing static wireframes, EPAM Continuum’s Hyman used Apple Keynote to develop a narrated walkthrough of the wireframes, showing both the customer- and merchant-facing digital wireframes suspended against a changing background of photographs taken during testing, and accompanied by a narration the app’s key features and explaining how they were tested with actual merchants and NMB microloan customers.

Following a successful presentation to both the extended team of stakeholders and NMB’s Board of Directors, the EPAM Continuum team spent the day working alongside the NMB core team to align upon the project’s implementation. While the original RfP that NMB shared requested that the responding bid include the full-fidelity development of all of the new service’s digital and physical touchpoints, EPAM Continuum team members advocated for a different approach; if EPAM Continuum led the development of the app from their headquarters in Boston, the process would risk being expensive, time-consuming, and not the most efficient use of NMB’s or EPAM Continuum’s resources. Instead, the EPAM Continuum team proposed to help NMB write a separate, additional RfP to distribute to local software development companies. By having a local Jordanian company collaborating with NMB to code and implement the full-fidelity version of the service’s digital touchpoints, the costs to NMB would be far lower, and any questions the software company had about the development process could be answered quickly and in-person.

On their final days in Jordan, the EPAM Continuum team worked closely with NMB to develop User Stories and a detailed work plan to help better guide and inform the local software developers who would be responding to NMB’s technical RfP, which was co-written with guidance from EPAM Continuum. NMB eventually chose to work with a Jordan-based software developer with a track record of developing digital services for several other major financial institutions in Jordan.

IMPLEMENTATION AND OUTCOMES

In April of 2018, NMB released a digital app that enabled customers to repay their microloans in a more flexible way by letting them choose the amount of money they paid out of the app’s associated e-wallet. NMB partnered with the Central Bank of Jordan to integrate the NMB app with the Central Bank’s “Mahfazti e-wallet,” a system developed by the Central Bank and run by the mobile network operator Umniah. Although technically enabling microloan customers to repay their loans remotely using their phone, the service requires the microloan customer to have first placed money into a Mahfazti e-wallet account, which can be done by visiting a participating local Umniah mobile vendor.

While the local software development company chose not to draw upon the cultural affordance of the e-hassalah, and NMB has not yet fully scaled the ability for customers to pay in cash at a local merchant and have that amount be considered in the same way as making a repayment at an NMB branch, the current service is a strong middle step along the way through enabling gradual repayment by paying money out of the Mahfazti e-wallet. Released in the spring of 2018, the Android version of the app (Android is the dominant mobile operating system amongst NMB’s customers) has been downloaded more than 1,000 times in the first three months it was on the market.

Multiple features of the app in its current form can be traced back to the evidence that the NMB/EPAM Continuum research team uncovered in the field and presented to the extended NMB team during the Analysis workshop. Informed by the findings of how customers struggled and improvised to keep track of their loans, the app lets users seeing both their total amount repaid on their current loan, as well as number of remaining repayments (both pieces of information that the research team heard respondents wish they had at their fingertips over the course of their field research). The app also presents NMB customers with a log of digital receipts that show all of their past successful payments, creating a “digital paper trail” to assuage the fear that some respondents in NMB/EPAM Continuum’s generative research shared, which was that money could ‘disappear’ within their smartphone without a trace. NMB’s service also lets users apply for a new microloan by using their phone to submit key documents and information, instead of forcing them to bring in physical copies of the documents (or informally use text messages to submit documents to NMB’s local branch employees, which the research team heard some respondents tell they did). These features, based upon the ethnographic data that the research team shared with NMB stakeholders throughout the process, speaks to the potential impact of the right form of evidence presented in the right way—even within organizations that haven’t previously relied upon the use of ethnography to understand and design for their customers.

Zach Hyman is a Design Strategist at EPAM Continuum who has previously worked across China, Myanmar/Burma, Jordan, Italy, Viet Nam, Thailand, Denmark, England, and the US designing both products and services for retail, IoT, healthcare, transportation, and education. He conducted Fulbright research into resource-constrained creativity across China, and blogs at SquareInchAnthro.com

NOTES

Support for EPAM Continuum’s engagement with the National Microfinance Bank of Jordan was generously provided by the United States Agency for International Development through their Jordan LENS Local Enterprise Support Project. This case study does not represent the official position of EPAM Continuum, USAID, or the National Microfinance Bank of Jordan.

REFERENCES CITED

Chipchase, Jan, and Lee John Phillips

2017 The Field Study Handbook. San Francisco: Field Institute

Jordanian Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation

2012 Jordan Microfinance Market Study. ProDev.

Madsbjerg, Christian, and Mikkel B. Rasmussen

2014 The Moment of Clarity: Using the Human Sciences to Solve Your Hardest Business Problems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press

Maurer, B., T.C. Nelms and S.C. Rea

2013 “‘Bridges to Cash’: Channelling Agency in Mobile Money,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 19 (1): 52-74

Payne, John

2015 Getting Beyond Use: Designing for meaning with cultural affordances. Presentation at Midwest UX 2015, Pittsburgh, PA.

Sanders, E. B., and Stappers, P. J.

2014 Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. Amsterdam: BIS.

Statista: The Statistics Portal

2017 “Number of credit card holders in the United States from 2000 to 2016, by type of credit card (in millions)” Statista website. Accessed June 4th, 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/245372/number-of-cardholders-by-credit-card-type/

Taylor, E.B. and H.A. Horst

2013 “From street to satellite: Mixing methods to understand mobile money users.” Proceedings of the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference, London, September 15-19, pp. 63-77.

Von Bayer, Sarah L.

2017 “Thinking Outside the Camp”: Education Solutions for Syrian Refugees in Jordan, EPIC 2017 Proceedings.

Young, Indi

2011 Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior. Brooklyn, New York: Rosenfeld Media.