If it’s summer in your part of the world (or even if it’s winter), you’ve probably been feeling the heat. On 5 July, Ouargla, Algeria recorded 51.3°C (124.3°F), the highest temperature ever reported in Africa. A few days later, Areni, Armenia hit a record 42.6°C (108.7°F), and on 17 July, Badufuss in Norway topped its charts at 33.5°C (92.3°F). Perhaps most disturbing were reports of people collapsing in the fields in Japan, where high humidity exacerbated record-breaking temperatures of over 40°C (104°F). Japan declared a natural disaster, a designation normally reserved for earthquakes and tsunamis.1

“Something is going on” – people feel – “but what?”

Of course, climate scientists have been beating their drums for decades, pushing out papers, reports, and campaigns about the risks of anthropogenic climate change. But dramatic and even deadly weather events are, it turns out, rather effective at opening opportunities for speaking about climate change across an unprecedented range of public fora. In these moments, people who have experienced and witnessed extreme weather call on climate science to answer a fundamental question of attribution: is climate-change to blame?

Many are eager to use these rare moments of public attention to sway public sentiment toward policy change, but the question of whether particular weather ‘events’ are evidence of climate change has a been perennially difficult one for climate scientists to answer.

When pressed to avow or disavow a link between weather and climate, scientists will generally begin by distinguishing these two phenomena. This is because the empirical evidence people experience – heat, fire, warnings, destruction – is not just different, but of a different order to the kind of evidence scientists use to construct an understanding of the climate.

Noting how ethnographers have long engaged in the “analysis of, and interpretation through, quantitative data at all scales and granularities,” Elizabeth Churchill emphasizes that this is a critical moment for an “embrace and a reconfiguration of what it means to render meaning into big and small data.” Moments when the experience of a blistering day turns public attention to the expertise of climate scientists provides one such opportunity to explore some of the thorniest of questions we face in the global, modelled, connected world in which we live: How does knowledge about phenomena we experience versus knowledge about complex, planetary-scale phenomena differ? How do certain kinds of evidence come to count? How can different kinds of truths about the world be made to speak to each other? And what does a changing world do to practices of evidencing?

Actualities and Probabilities

This summer, climate scientists whom I follow—both academically and on social media output—began to talk with some excitement about the appearance of what seemed to be almost real-time attribution studies. These studies were able to assess, whilst the European heat wave was still happening, whether the heat was the result of climate change or a normal temperature anomaly. This calculative operation doesn’t literally equate weather to climate. Rather, the technique works by transforming weather (in the form of heat measurements from different weather stations across a geographical area) into a ‘snapshot’ of climate that can then be compared to other probable climatic conditions in different times and under different hypothetical conditions.

As a non–climate scientist, I’m intrigued how this kind of calculation creates the possibility that weather, the local manifestation of complex global climatic flows and relations, can be classified as being unrelated to climate change without undermining the claim that climate change is happening.

It seems paradoxical: If global climate is a description of all weather, and if climate change is happening, then surely all weather is by definition evidence of climate change? Attribution studies, however, are able to separate out weather that is climate change from weather that is not climate change by deploying techniques of statistical analysis that redescribe weather not in terms of actualities, but in terms of probabilities.

Reading the technical report from the attribution study on the heat wave in Europe is not easy for a non-scientist of climate. The crucial part of the report which describes how the temperature of Europe during the heat wave was established for the purpose of analysis, explains:

“As appropriate for our event definition, we fit a Generalized Extreme Value Distribution (GEV), described by three parameters: the position parameter μ, the scale parameter σ and the shape parameter ξ. In this statistical approach, global warming is factored in by allowing the fit to the distribution to be a function of the (low-pass filtered) global mean surface temperature (GMST), where GMST is taken from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Institute for Space Science (GISS) surface temperature analysis (GISTEMP, Hansen et al., 2010). We assume that the scale parameter σ shifts with the position parameter μ, thus the PDF is shifted up or down with GMST but does not change shape. In this way, it results in a distribution that varies continuously with GMST. This distribution can be evaluated for a GMST in the past (e.g., 1950 or 1900) and for the current GMST. A 1000-member non-parametric bootstrap procedure is used to estimate confidence intervals for the fit.”2

This describes an operation in which (bear with me) temperature measures from specific weather stations in different locations across Europe are mapped and then compared to a global mean surface temperature to determine whether or not observed weather (over any 3-day period) deviates from the historical average. This information is then compared to several climate models which are run under different scenarios. The aim is to understand whether the pattern of observed anomalies is more or less likely under conditions in which anthropogenically created global warming is occurring. Using this method the authors were able to rapidly publish an analysis that demonstrated that anthropogenic climate change had made the European heat wave of 2018 more than twice as likely than if no global warming had occurred.

The problem of climate change is often framed as one of truth – and whose truth counts. But actually what we have is not a problem of truth but of evidence. Both the fact of searing heat in which people collapse on the street with heat exhaustion, and the fact of the same weather as an example of something bigger than itself, are ‘true’, if by truth we mean that they have both material foundations and a constructed nature. But the forms of evidence that are deployed to establish such truths are fundamentally different, and crucially, this difference has mattered, at least until now.

Science and Experience

Back in the heat wave of summer, weather has been taking its toll. In Mati in Greece, at least 88 people die in the worst forest fire that Greece has seen, in terms of loss of life, in living memory. Photographs of the aftermath are apocalyptic. People are furious.

But here, the question of whether climate change is to blame becomes side-lined by other kinds of evidence about the entanglements of weather, landscape and politics and the changes that they index: evidence that the austerity measures imposed by the Greek State had led to 30% cuts in fire service budgets, meaning fire-fighters could not get to the scene on time; evidence that fire hydrants were dry in part due to the privatisation of the water industry and their cost-cutting initiatives; evidence that rapacious developers had built houses on the floodplains of former streams increasing the vulnerability of the village.

This evidence is both more and less tangible than evidence that the heat wave was an example of climate change. On the one hand, the images, cardinal numbers and personal testimonies through which stories about tragedies like this are told mount up to produce a vivid description of the way in which heat waves can have catastrophic consequences. Empirical evidence of on-the-ground events lends a realism to the scientific descriptions of climate change.

On the other hand, compared to the structures of veracity and trust provided by traceable, state-sanctioned weather stations and established statistical methods, crafted stories of tragedy and politics represented through an aesthetics of apocalypse and austerity and circulated through the notoriously unstable channels of social media, lack the precision of scientific claims. The science that predicted climate change appears as more accurate than people’s stories. At the same time personal experiences in other moments seem more viscerally real than abstract models and predictions of scientific models.

Ethnographers are well used to the appearance of an ‘evidential gap’ between data and experience in issues of public concern. From vaccines to pandemics, from the voting behaviour of the population to the viral effects of social media, digital data and modelling techniques are well known to separate phenomena out into general tendencies on the one hand, and everyday effects on the other. Typically these different ways of evidencing are kept separate: in global climate change, climate scientists speak for the climate. The media or politicians speak for the public and their concerns. Ethnographers also usually inhabit one side of this opposition, most commonly aligning themselves with local experience rather than with the production of universals. But could the advent of heat waves and other kinds of extreme weather create an opportunity for new kinds of traffic across this divide? Could the local manifestation of climate change actually have the power to alter the ways in which evidence about climate change is itself is made? Might it provide us with an alternative way of describing global processes and their local effects?

Evidence We Need for the World We Make

Attribution studies are one way in which climate scientists are trying to shrink the gap. Although the attribution study cited above retained the opposition between climate and weather, it also used observations from specific weather stations rather than averages of weather across geographical areas in the construction of the model. This had the effect of tying the analysis more closely to extreme weather in specific places.

Moreover, what was so exciting about this summer’s attribution study was that it enabled climate change and weather to be talked about whilst the weather in question was still happening. The temporality of the study, designed to be inserted into public debate at a time when people were experiencing the effects of extreme weather, can also be seen as a gap-shrinking exercise, where science and experience were brought into temporal alignment with one another with potentially world-changing effects.

An example of work in a similar vein is conversations among an interdisciplinary group of scientists and practitioners at University College London about the way in which climate science addresses risk. Responding to flood-risk analysts working in government who have pointed out that existing climate data just doesn’t fit their way of planning for uncertain futures, climate scientists have begun to consider whether they might need to create new kinds of evidence that describe not just the most likely climatic future that will occur, but the likelihood of specifically disruptive or catastrophic events.

Here the question shifts from one about the nature of global climate, to one about the nature of catastrophe. With this the door opens for other kinds of evidence to flood in – evidence about infrastructure, about politics, about need, about human experience, about sanitation, funding and social organisation. The evidential gap that has kept weather separate from climate here again begins to close, creating a new terrain of knowledge in which different kinds of facts are created and new kinds of knowledges formed.

In the lived conditions of climate change, when the effects of such changes are only catastrophic because of their political, social, existential and moral dimensions, questions of evidence that have structured the study of earth systems are quietly being transformed by weather’s manifestation in human worlds. Weather is not climate, but weather does, it seems, have the power to shape the science of climate change in ways that are rarely recognised. Weather – as a local, political, social, environmental problem – is now forcing people to find new ways to bridge evidential gaps – between scientists and policy makers, global problems and local experiences.

But it is not just the creators of scientific knowledge who need to think about the place of evidence in processes like anthropogenic climate change. As ethnographers we too should allow ourselves to be affected by such events: to think anew about how to speak across scale, talk back to data, and weave everyday stories into issues of global public concern. Elizabeth Churchill’s call for new “data dialects” is grounded in this commitment to make collective connections across domains, to create synergies and cross boundaries. In order to speak back to global problems we will need to learn from each other and from the way scientists are confronting these issues. Only collectively will we be able to reflect adequately on our own forms of evidence and how they might need to change to remain relevant to the changing world that we find ourselves in.

Notes

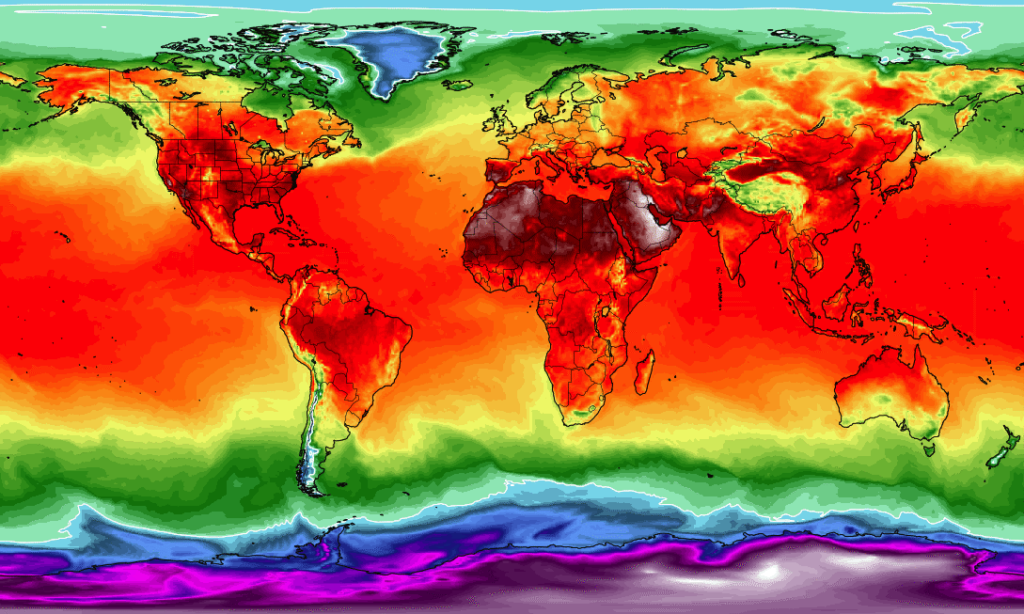

Image: NOAA / National Weather Service – National Centers for Environmental Prediction – Climate Prediction Center

1. All data from the taken from the World Meteorological Association https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/july-sees-extreme-weather-high-impacts

2. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/attribution-of-the-2018-heat-in-northern-europe/

Hannah Knox is Associate Professor of Anthropology at University College London. Her books include Roads: An Ethnography of Infrastructure and Expertise and most recently Ethnography for a Data-Saturated World, which she co-edited with Dawn Nafus. Her current research explores the profound cultural, epistemological and anthropological challenges posed by global climate change.

Hannah Knox is Associate Professor of Anthropology at University College London. Her books include Roads: An Ethnography of Infrastructure and Expertise and most recently Ethnography for a Data-Saturated World, which she co-edited with Dawn Nafus. Her current research explores the profound cultural, epistemological and anthropological challenges posed by global climate change.

Related

Sustainability and Ethnography in Business, Mike Youngblood

Data Science & Ethnography, Tye Rattenbury & Dawn Nafus

The Domestication of Data, Dawn Nafus

0 Comments