Case Study—This case study discusses the role ethnography played in fostering collaboration across two organizations during a research project. It explores how the opportunity for collaboration emerged, why it was seized upon, and what it meant for the project. The case study looks at the project challenges and mishaps and clarifies why in spite of this it is believed to be successful. It analyses the impact on people’s perceptions of the project outcome and what this meant for our client.

Keywords: organizational culture, agency collaboration, design research, government

INTRODUCTION

Caitlyn1 was a manager within the Injury Prevention branch of a state owned enterprise, responsible for providing no-fault personal injury coverage, called Injury and Accident Insurers (IAI). She was wondering how to address internal pressure to deliver results. Her team had done a year of work to produce a set of best practice guidelines for farm forestry health and safety. They had briefly paused and were close to completion when the environment changed. A new player had emerged, a government organization, which might have been seen as responsible for the scope of what Caitlyn’s team had been working on. She then had to consider whether or not to continue developing this set of guidelines for market.

BACKGROUND

During the 1990s, the economic climate encouraged widespread planting of small woodlots throughout the New Zealand rural sector. Harvesting would begin towards the end of the decade, i.e. between 25 and 30 years of growth. This looming harvest is commonly referred to as the ‘wood wall’. The existing assumption in IAI was that harvesting time would see an increase in forestry activity. The belief was that this, coupled with an increase in new inexperienced harvesters, would result in an increase in forestry injuries and therefore an increase in claims. The organization wanted their Injury Prevention unit to address this.

Caitlyn’s team had been working on a practice guide for the farm forestry sector to help improve health and safety as well as other business practices. A year’s worth of research and stakeholder management had taken place and the guidelines were nearly complete when the project was put on pause. After the pause, when the team went to readdress the best practice guidelines they found their context had changed. Amongst the changes was the development of a new government organization Health and Safety at Work (HSW) that had been established with the specific aim to address workplace health and safety.

The context had also changed because IAI had redefined its strategy and focus. The organization was particularly interested in innovation. They were aiming to effectively deliver initiatives that were focused on their customers and would work alongside other branches in the organization to do so.

There was a perception amongst IAI that HSW was complicated to work with. The new organization was still defining its role and scope in the pre-existing market. It was perceived to be young and “having a tough time of it”.

START OF THE PROJECT

Caitlyn decided to approach a group of consultants, Empathy, who had a long-term relationship with the organization. Empathy had been involved in helping them to shape their recently defined approach to innovation.

Caitlyn explained to Sarah from Empathy that the organization was looking for quick win initiatives, projects that could be achieved in three months. The Injury Prevention unit’s work addressing farm forestry had been identified as one such initiative. However, she had concerns that even though their work was near the finish line and, given their new ecosystem, implementing the guidelines might not be the best way forward.

Caitlyn was looking for someone to help her team figure out how to move forward and address the farm forestry issue. She wanted this done effectively and within the new practice framework of the organization that she also recognized her team might need coaching through.

Empathy came on board in a ‘facilitator’ and coaching role to build capability amongst Caitlyn’s team. Empathy also understood that they might work alongside Caitlyn’s team to bolster project team numbers when necessary. In their proposal to Caitlyn they laid out a first phase of work to assess the current guidelines and make a call on whether they should be taken to market. Given this would partly be dependent on HSW’s role, Empathy suggested this phase be done with involvement from HSW. A second phase of work was included to facilitate and work alongside Caitlyn’s team to either: shape, refine and implement guidelines or explore the new approach.

Phase One – Assessing Current Guidelines

A workshop was held with people from both IAI and HSW. Empathy held the workshop at their offices to provide some neutral ground. Sarah who was lead consultant and had been talking to Caitlyn facilitated the session. As Sarah described it, “There is palpable tension in the room as the ‘main guy’ representing HSW shows up late for the session. He’s assumed it would be held at IAI. You can tell both sides feel like the others could’ve done better, but they’re good people so nobody says much about it.”

They went through the session, trying to gather insight from each other to decide whether the guidelines should be finished and sent to market. Sarah’s role became to ensure different points of view were considered, they didn’t rush to make a decision and were mindful of the implications.

From early on there were some people that didn’t see enough evidence to suggest the practice guidelines were a great idea. They began to wonder about their knowledge of the audience. Others disagreed and felt pressure to produce something after a year of work. People felt bad for the amount of work already done by Thomas, the lead on the practice guidelines. The suggestion to “just do it anyway” — to finish the guidelines and put them into the market — was floated around the room. “We’ve come this far, let’s finish it,” said one participant.

Counter-arguments to this were shared by those concerned by the loss of good will that might be engendered by putting a campaign in to the market that didn’t actually suit the target audience. Another question arose around “what would it mean for forestry workers to see this?” It became clear they didn’t know the answer. This prompted concerns about the potential media embarrassment of being out of touch, as well as the time and money that was still required to finish the guidelines and get them out to market.

At the end of the workshop, the group decided not to go ahead with publishing the practice guidelines. Instead they decided to continue into the second phase of work, where they hoped to understand where and what IAI’s focus should be with regard to farm forestry. To address the discussion around the lack of evidence for a practice guide Empathy suggested using ethnographic methods in defining this approach. Sarah also reinforced the value of IAI and HSW continuing to work together.

EXPLORING THE BUSINESS PROBLEM

Caitlyn’s team and Empathy moved forward with the second phase. Given phase two was taking more of an exploratory focus than an implementation one, Empathy decided to reassign their lead consultant. Sarah stepped out of the project and handed over the reins to Erin. Similarly, Caitlyn remained involved as manager, but Thomas, as the team’s expert in the forestry space became the project lead. Together, Thomas, his team and Erin became the ‘project team’.

The first working session Erin ran with Thomas’s team was aimed at understanding the business context and drivers for addressing farm forestry injury prevention. As Erin put it, “Why are we going to be putting resources into this project?”

They explored the current pain points IAI had with respect to farm forestry, what had already been done before, who the other players in this space were, as well as the current ‘vibe’ of IAI and their stakeholders.

IAI had an instinctive sense that it was small-scale forestry that posed a looming problem. Forest management companies had more formal systems and processes in place and were less likely to pose a risk. However, the team didn’t have specific numbers.

As a group they also discussed the problem with media sensationalizing the lack of safety in the forestry industry. They identified that this shaped the public perception towards forestry, and many people seemed to believe it was dangerous and not much was being done to address it. They ended the session agreeing to find out more.

They learned that small-scale forestry was an incredibly diverse sector, with a lack of definition for what ‘small-scale’ really meant. It included absentee growers, farm forestry, small-scale forestry and non-corporate forestry. It was unclear which group they should focus on and where the potential problems were. In addition, the team didn’t have enough information to understand the basis of the health and safety problem. They wondered if it had to do with foresters’ indifference to safety, poor equipment standards, or a lack of skilled labor. Erin actually asked if health and safety was a problem at all.

When they looked through Thomas’s data they found that IAI’s concern with increasing claims was not reflected in their numbers. In fact, compared to other industries forestry appeared to be doing well avoiding injuries that lead to entitlement claims. Thomas and his team began to notice there was no strong financial reason for IAI to invest any further in the project. However, they also continued to receive increasing internal pressure to do something about forestry.

Despite the apparent lack of increasing claims, there had still been a number of tragedies in the forestry industry over the previous years, and there was a strong belief this needed to be addressed. In addition, there was still a problem with poor public perception and media coverage. There were remaining concerns that as the ‘wood wall’ came into full swing the number of accident and fatality incidents would further increase.

Thomas’s team made a call to move forward. With the lack of numbers highlighting an issue, they recognized the business problem was still vague. They decided to learn more about small-scale forestry before going out into the field. Erin asked, “Where can we go to learn more?” Thomas answered, explaining it was HSW’s Health and Safety (H&S) inspectors who had the most experience on the ground and first-hand knowledge of the potential hot spots. H&S inspectors were “the people who are in the field all the time.”

The overarching relationship between IAI and HSW had not improved at this point. Although, Thomas’s direct relationship with his counterpart, Alan, was healthy enough.

Thomas and the team believed that working with HSW was important but also a potential risk to the project. Regardless, HSW was seen as a key stakeholder. So Thomas and his team decided to reach out to HSW by treading carefully and managing it closely from a relationship and communications perspective.

INCORPORATING EXPERT UNDERSTANDING

It took Thomas and Erin several meetings to shape their plan for engagement with HSW. They had to define the value for HSW so they would be willing to participate. Even though both organizations were being told to work together from above, things were not straightforward. Internally each of their cultures was saying ‘we don’t work well together’. Senior leadership understood this and decided that what they needed was an example of successful collaboration. Getting HSW involved with Thomas’s project was seen as an opportunity to do this. Eventually, HSW decided to get on board for a workshop where their staff would get to have their say.

Thomas and Erin began to work with Alan from HSW. They all understood that this next piece of work relied on the H&S inspectors being happy to engage. Inspectors worked across the country and were often in the field. Thomas, Erin and Alan decided the most effective way to gain knowledge from them would be to run a full-day workshop. Erin liaised with Alan to understand the mindset and attitude of most inspectors. They used this understanding to design a workshop approach that would work for inspectors.

The aim of the workshop was to understand the inspectors’ perspective around who to include as a small-scale forester, who was at risk, how these foresters operated, as well as where and why there were safety issues.

The workshop

There were 12 HSW frontline representatives in attendance, a combination of inspectors and managers. A further 15 attended from IAI. Erin facilitated the morning session by setting the tone, initiating the conversation with inspectors and managers, prompting them, exploring their stories and digging deep along the way. She asked the other attendees to take notes of what frontline staff had to say. Thomas and Alan co-facilitated the afternoon session to reinforce the partnership between their two organizations.

HSW staff explained the distinction between farm forestry and forestry on small woodlots. They discussed various factors that raised safety concerns – forestry contractors had low profit margins, and forestry activity was highly influenced by market conditions, likely encouraging contractors to go all out when prices were up or forcing them to cut costs when prices were down. They also made a point of distinguishing between full-time permanent small-scale forestry contractors, casual forestry contractors and forest owners.

Frontline HSW staff also noted the sector was under regulated and dealt with inconsistently. From their point of view reasons for this included the remote areas forestry contractors worked in, as well as their regular travel and temporary stays in locations.

During the course of the workshop more and more staff from HSW got on board with the work IAI was doing. They supported the approach and insisted that any intervention in this space needed to be specifically tailored to the target audience and the unique environment they worked in.

Together, workshop attendees decided that to gain more valuable insight of the target audience during fieldwork, the project team (Thomas’s team and Erin) should focus on a specific subset of forestry workers. These were defined as:

- Workers operating in small-scale forestry (less than 10 hectares)

- Non-corporate foresters

- Full-time and all year round (not seasonal) workers

- Crews of 2-4 workers.

Next steps

As a result of the workshop, Thomas drafted a report that documented what they had learned. This report was shared with HSW.

With the target audience defined jointly in the workshop, the project team then prepared for fieldwork. HSW agreed to play a role in recruiting forestry workers for the IAI project team to engage with during the fieldwork phase. HSW believed that with their people on the ground they were best placed to reach out to foresters. The project team appreciated the help.

The restructure

Before the project team got a chance to go out into the field with forestry workers or get any recruitment done, IAI underwent a severe restructure. This caused a lot of uncertainty within the organization. Senior leaders were changing across the board. Whole teams and units were being restructured.

The project was put on hold while the organization went through the change and settled into the outcome. Five months passed.

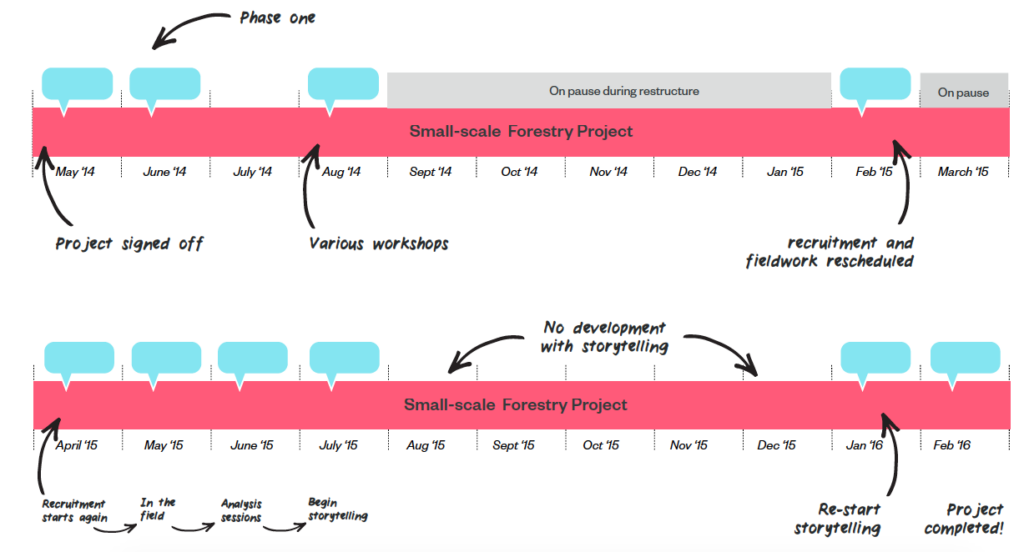

The image below illustrates the dates when project activities actually occurred.

Figure 1. Timeframe of project engagements.

GAINING CUSTOMER INSIGHT

When Thomas was finally in a position to work on the project he reached out to Erin to kick things off again. However, he had a heavy workload and several of his original team members were no longer assigned to his area. Originally, Thomas and his colleagues were going to be conducting fieldwork themselves. Erin, in her role as consultant, had planned to add to the team’s numbers if needed and facilitate and coach them along the way. Given Thomas’s workload, it was decided that he needed more people to take an active role in the project. Erin got her colleague Natalie to join the project. From here, Erin and Natalie both took on more of a ‘doing’ rather than ‘coaching’ role by agreeing to conduct fieldwork themselves while bringing some of Thomas’s team along.

IAI got in touch with Alan to ask for his help with recruitment of forestry workers as had originally been intended.

At first recruitment showed little promise. HSW passed on a limited number of replies to IAI, who attempted to recruit before eventually passing on the details to Natalie. Natalie also tried to recruit with no luck. She learned it was the wrong time of year to engage with forestry workers as it was prime harvesting time and they all felt too busy to participate. As Natalie noted, “No one would pick up before 7pm, and then even if they were interested they’d say they couldn’t do it this month.” The project team decided it would be inconsiderate to their target audience if they continued with recruitment. The project was paused once again and scheduled for a later more appropriate time.

Two months later

HSW sent out information to forestry workers on behalf of IAI. They got a few more potential participants and Natalie restarted recruitment. Despite the two-month wait, recruitment was still slow. Foresters, while willing to participate, were not happy committing to engaging with someone on a specific date. This made it hard to arrange from a logistical point of view. In addition, not enough names had been provided to reach recruitment targets. The project team explored using different approaches to recruitment, including snowballing and cold calling. Eventually, recruitment targets were met.

In the field

Forestry workers’ lack of availability meant the project team prioritized the participant’s schedule over their own. In the end this meant that only Thomas, Natalie and Erin were able to go out into the field. Between the three of them, they engaged with 12 main participants consisting of a combination of forestry contractors and their employees. In addition to these 12 they also interacted directly and in passing with various other foresters. This occurred because they were members of the same crew, friends of participants, or simply due to the prevalence of foresters in the area.

Meeting with people in their homes, Natalie discovered the pride and importance forestry contractors gave to their work. It came across in their lifestyle, and spoke to their apparent ‘rough culture’ — and their sense of pride even came across in their choice of décor. One forestry contractor that Natalie and Thomas engaged with had a photo of his skidder printed on canvas and hanging in the dining room. The contractor told them how after years as a forestry worker he had been able to get enough money to buy it. This had enabled him to start working for himself as opposed to sub-contracting out to someone who had the equipment but needed his services. As a new forestry contractor times had been tough. His first season was an especially bad one. His existing contacts had been key in getting him through it. But, he believed it had been worth the effort. Now he was able to run a crew of four guys.

On a site visit Erin was able to see the advantages of having a small crew. Whilst engaging with a forestry contractor it came time for morning break and they all paused to get together. “We always take smoko together,” they explained to her. “It’s good — it makes you feel like a team.” They were mindful of doing this together, commenting that “H&S is all about communication” and “no one is better than anyone else we take advice from each other.” Then, some of them took the opportunity to show her the manuals they use, the thin, copy based New Zealand one wasn’t much use to them, but the thicker and image based Canadian manual was a favorite.

Figure 2. Showing manuals over ‘smoko’ (morning tea break).

In their engagements and visits with forestry workers Natalie, Thomas and Erin began to notice a trend. They spent several hours talking about it while on the road. Forestry workers felt safer than before. The team had heard stories of what it was like when people were young and heard over and over again that “the industry has cleaned up.” Outside of the industry there was a perception that forestry workers were cowboys, this was something that some of the forestry workers they spoke to also believed, and yet none of them could point them towards the ‘problem-people’. “I’ll tell you it’s frustrating when you’re working hard to be better but you don’t hear about the good ones, you only hear about the bad ones (…) they tell you, ‘ah you must be a rough…’ when you’re not,” one worker said.

Analysis and definition

After fieldwork the project team arranged to get back together to share their experiences in the field and make sense of what they learned. Alan and some of his colleagues from HSW were invited to join the immersive analysis workshop. Erin said this was actively done “in order to foster collaboration.” At this stage Thomas and Erin were aware that IAI was interested in continuing to fund the project, but was potentially interested in having HSW in charge of implementing the initiatives that resulted from this work. This was in line with IAI’s new strategy post-restructure.

On the day of the analysis workshop the project team shared their stories from the field with others. They were able to compare Thomas, Natalie and Erin’s learnings with Alan and his HSW colleagues’ experience on the ground and working with foresters. This created a joint understanding. Alan was able to add the wider view of what HSW sees happening on the ground, which added richness and context to the stories being discussed. Meanwhile, IAI’s field stories added a different perspective to HSW’s understanding.

They heard about how difficult it was becoming to hire people with experience. Some contractors took the time and cost to ensure their crew was well trained by making sure they got all their certificates — but there were mixed perceptions in the industry as to whether this was a good investment or not. Someone well trained could leave you. As one person said, “Every extra ticket goes on their CV, and if they decided to leave they could easily work somewhere else.” Alongside this there was a fear that experienced people were leaving the forestry sector and “the loss of experience is creating risk.”

The project team also heard stories about the amount of time it took to do paperwork in an industry with low margins and high production pressures. Stories from the field noted “safety costs us our profit margin”, “the cost of compliance is going up” and “it’s all about the paper trail to cover your ass” but, “regulation won’t stop someone from doing something stupid.” Despite this attitude towards regulation, they also heard stories about how well the crew knew each other and how they watched out for each other because they knew each other’s families. Crew members understood what their team members were going home to, and at the end of the day “being a dad is more important than work.”

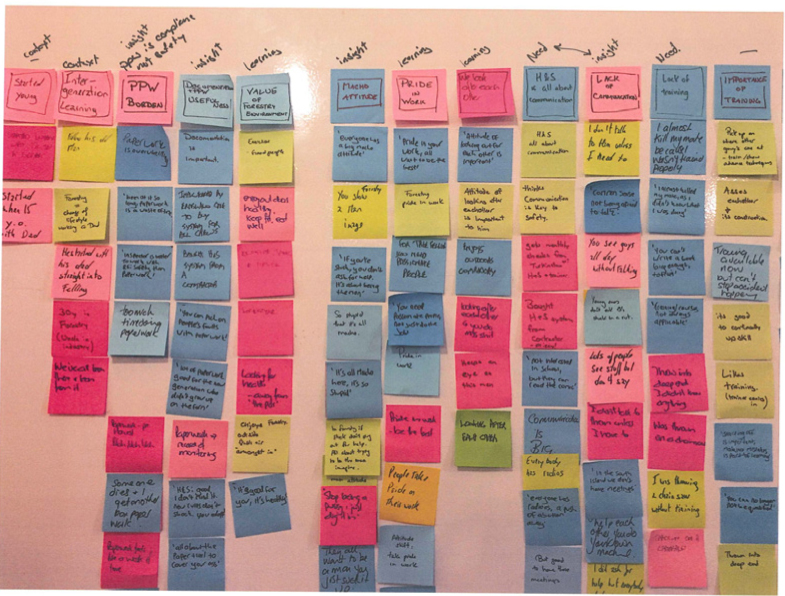

Once they shared stories they started pulling out emerging themes, patterns and discrepancies. The ‘extended project team’ worked together to decide how to group different observations, quotes and learnings under each theme. Particular care was taken from Erin and Natalie to encourage team members from both organizations to ensure that all data points grouped together spoke to the same theme and that the emergent theme was the most accurate representation of that learning. Discussion between team members reconnected people with foresters’ stories and challenged any biases and assumptions that came out along the way.

Figure 3. Examples of emergent themes.

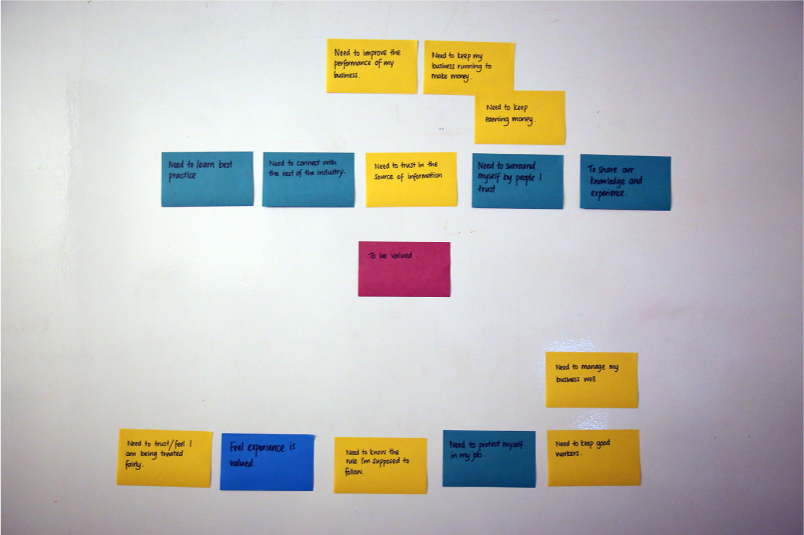

From there the team got to work identifying foresters’ needs in relation to workplace health and safety. Erin and Natalie facilitated a ‘why-how laddering’ activity to explore a variety of needs and then to further identify the level at which Thomas and Alan’s organizations should be playing at. This activity explored various types of needs and placed them hierarchically in relation to each other. It uncovered the overarching needs foresters had, such as ‘to keep their business running’, ‘to provide for their families’, etc. It also explored the needs that related to specific details for example ‘to keep up to date equipment’. Through asking either how or why foresters would address those needs, more needs emerged. By continuing to place them in this hierarchical relation to each other people could start to see the needs that fell within scope for their organizations. After some discussion and a voting session they arrived at the series of needs they felt they should be addressing. Team members then paired up to create point of view statements that centered on these needs. These were then shared and discussed with all attendees.

Figure 4. ‘Why-how laddering’ needs activity.

At the end of the two-day intensive analysis session the team wrapped and reflected on how easy it had been to collaborate and how glad they were to continue collaborating. Alan appreciated where the work had got to, and Thomas was glad that Alan was on board. Thomas explained he hoped HSW would be the ones taking action as a result of the customer insight. Alan agreed that was what this work should lead to.

STORYTELLING

Originally IAI was going to document what was learnt. This had been agreed at the outset, when it was established that Erin’s primary role was to coach and most of the IAI team was to do fieldwork. Despite the changes that had occurred since then, given Thomas had been involved in every activity the original plan was followed. Thomas would be doing most of the documentation and storytelling back to IAI and Erin was going to coach him through the process.

Shortly after the analysis and definition session the pair met to discuss the story. Thomas brought his perspective of IAI, how they worked, what he thought they needed to hear, etc. Erin shared her experience storytelling this type of projects to clients. Together, they defined the structure of the document. The pair continued to work in this way over a couple of sessions where they explored the structure and content, Thomas then planned to develop it.

During this time, there was further restructuring within the organization and more people left. Thomas became the most senior and experienced person left in his section. He ended up “acting as his own manager” and all of his “previous program work was put on hold.” Nearly three months passed before Thomas was able to renew his role and work with a new person as his manager. At that point, with a large workload that had been on hold, Thomas asked Erin, “Can you please help me, can you please just do the documentation?” Erin then worked with Natalie and a writer on their team to create the document. As they refined the story and outcomes of the analysis and definition session, they ended up writing a series of design principles for future health and safety initiatives with forestry workers.

Outcomes

The document was delivered. Twenty-two months had passed since Caitlyn, Thomas’s former manager, contacted the consultancy. Twenty months had passed since the first workshop session and deciding more evidence was required to define the organization’s approach to injury prevention amongst forestry workers.

The report was circulated and shared across IAI, HSW and their industry forum for forestry. The report positioned IAI as a further expert in the room alongside HSW and the industry forum’s knowledge of the sector. Thomas continued his working relationship with Alan. HSW officially became IAI’s partner in this initiative and their roles and scope were further refined. It was agreed that since the forestry industry body could connect with larger, corporate forestry operations HSW’s purview would become the small-scale forestry that had been targeted through the IAI project and report. IAI’s role became more clearly defined as the organization that would offer HSW support throughout this process, whether it be through funding or sharing their expertise.

A key outcome for IAI was the shift in thinking about forestry workers as ‘cowboys’ and ‘the problem’ towards a better understanding of their context, the constraints of the industry they were operating in and their mindset to safety.

A few months later, HSW had shaped an action plan for engagement with forestry workers to begin the following year.

DISCUSSION

The original project concept was meant to last three months. This would assess the health and safety best practice guidelines for forestry workers, and then decide to either implement these or work to uncover the organization’s new approach to injury prevention with forestry workers. As soon as there was a pause between the first phase and the second phase this timeline became unrealistic. However, for it to have taken 22 months is both unfortunate and a clear failure for a project intending to be a quick win.

The reasons for this failure are not straightforward. Was it a mistake to believe a weighty topic such as health and safety and injury prevention amongst a controversial, heavily media covered industry could be a quick win? Could the internal project team members have accommodated for the organization’s restructure? How might members from IAI, HSW and Empathy have better prepared themselves for recruitment? Given the history of the project, why was Empathy’s coaching role continued? Would a more active role have been more appropriate from the outset of documentation?

On the other hand, this project avoided the money and time expenditure of further developing the best practice guidelines and sending them to market. What’s more we learned that this level of intervention does not meet forestry workers’ needs.

From a financial point of view, with the exception of the variation to include Natalie’s work and additional documentation work in the project, it was carried out for the original amount the consultancy had agreed to. It could be said that the pauses as a result of the restructure played a significant impact on the project but were not in themselves project failures. One might argue these pauses were out of the project’s control, as they not only affected the Injury Prevention branch but the wider organization.

For IAI, which needed to be seen to be doing something about forestry, doing the project in itself met the brief to some extent. They were able to both directly engage with forestry workers, potentially strengthening their presence in the community, and work with HSW ‘the new government organization’ in this space.

This brings us to a further point. The purpose of this project was multi-layered from the start. IAI wanted:

- A quick-win project (not achieved)

- A customer-focused initiative that would follow their new practice framework

- To build capability amongst its team members through the project

- To make a call on whether or not to publish best practice guidelines.

As we continued through the problem definition phase we found that there was no strong financial reason to do the project, but other concerns and external perceptions were placing enough pressure for it to be worthwhile doing. We also realized that both IAI and HSW were pushing to prove they could work together and were eager to use this project as a case study for doing so. It is through the lens of this last point that the project is viewed as a success. This became a surprising outcome for the consultants and an important lesson to learn.

At a behavior change level the biggest impact to date actually occurred in enabling these two organizations, HSW and IAI, to be strong collaborators. It is interesting to look at how this came about, as well as what it means for success to be defined in this way.

In some ways this project, and specifically the doing of ethnography, became the vehicle for collaboration. Thomas and Alan already had a healthy working relationship and an interest in the outcomes for forestry workers. As a pair, they were good collaborators anyway. However, the amount of meetings that needed to be conducted at the beginning to discuss the potential involvement of HSW suggest that without prompting and a need for a better understanding of their target audience, this collaboration would not have occurred to the extent it did and has continued to.

For both organizations, collaboration was still firmly in their best interest. For IAI working with HSW is directly in line with their new strategy to support a partner organization to operationalize initiatives. Likewise, for HSW, as a recently set up government agency, being funded externally to do the work would have strong appeal. There are clear motivations for collaboration beyond a mandate to do so and a shared problem. At an organization level there just hadn’t been enough collaboration already occurring to understand what this would mean for HSW and IAI.

This allows us to look at the role ethnography did play (amongst these other drivers) in fostering this collaboration between organizations. We see both intentional and unintentional contributions.

- The initial perception that we needed to better understand the audience and that this might require ethnographic work helped project team members identify gaps in their knowledge. Being able to see these gaps in knowledge prompted the question, ‘who can fill them?’, which became the initial driver for stronger collaboration with HSW.

- Taking an ethnographic approach to understanding HSW’s frontline staff allowed the project team to facilitate a workshop that narrowed in on their target audience, shared knowledge across both organizations, allowed inspectors to feel heard by the people in national office, and got people from HSW on board with the project approach.

- Recruitment saw several issues. Rather than facilitating collaboration, the intentional collaboration through this process added extra steps and complicated recruitment. However, it also became a symbol to foresters and people within IAI and HSW that both groups were working together.

- Fieldwork in itself, what most would think of as the primary ‘ethnographic moment’, was not a particular spark for collaboration since only Thomas was able to join Erin and Natalie in the end. However, the result of Thomas being in the field, and therefore IAI also generating on the ground knowledge seems to have helped bridge views with HSW. As Thomas explained, “It has helped have different conversations.” He explained that in the past, they might have disagreed with HSW’s views on something and wanted to put IAI’s views “on the table to counter-argue but had no ammunition.”

- Analysis and definition proved to be one of the strongest enablers and examples of collaboration. It was carried out in Erin and Natalie’s offices both for suitability of purpose and as a neutral ground. The intensive session encouraged the extended team members to gain empathy for the same people, fall in love with the same issues, discuss, shape and clarify their understandings of foresters mindset, and work together towards identifying their needs. Crucially, it didn’t just allow IAI and HSW to share a similar view, but it actually offered a different perspective to the prevailing HSW one at the time. As Thomas described, “HSW came with the workplace perspective, we gave the more personal touch to the discussion.” It allowed IAI to “slowly try and change the perception of the problem — it’s not these people (foresters) that are the problem, it’s the context of their industry.”

- The ability to then share this knowledge through storytelling and specific documentation reinforced the willingness amongst the organizations to collaborate. The documentation itself, celebrated the collaboration as a successful outcome of the project.

CONCLUSION

As consultants the project felt like a ‘comedy of errors’. It also highlighted the strength of the role ethnography played. Despite the unfortunate events and false starts the ethnographic work was meaningful enough to make a big impact and turn this into a success. The fact that it did not run smoothly has cemented the author’s understanding that success can be more ambiguously defined. In this instance, a recommended project approach, i.e. to collaborate with another agency, became through the course of the project, one of the main purposes for the work itself. These changing drivers for a project’s purpose might be especially clear on an unintentionally long project such as this. We argue the practice and facilitation of ethnography by a consultant party played a strong role in enabling these two organizations to collaborate. We also acknowledge the role political and financial motivators played. Strong collaboration as an outcome in itself makes the project successful for both IAI and HSW. However, we believe the reason the project was successful goes beyond the internal politics of both organizations. The best opportunity for a successful intervention with forestry workers arose when the two organizations effectively worked together. Each organization had insights and strengths to offer to the initiative. The opportunity was ripe to combine these insights to provide a single message and proof of clear government involvement in this area. Forestry workers, as a result, can experience a clearly defined engagement program that speaks to them and suits their needs.

Daniela Cuaron is a Business Designer at Empathy. She is a graduate of the University of Cambridge where she studied Social Anthropology. Daniela conducted ethnographic research in Mexico before joining Empathy. Her work sees her striving to understand people’s unmet needs and creating ways to address these.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – I would like to thank Thomas, Erin, Sarah and others involved in this project for sharing their stories and perceptions of the project and helping this story get told, you know who you are. My gratitude also goes to MaiLynn and Matt for offering an outsiders perspective and helping shape the story. Gary, thank you for your feedback throughout this process, for your help in shaping my thoughts and for taking the time to answer my many questions, you’re help was invaluable.

1Names of people and organizations have been changed for anonymity.