Questions of scale permeate current approaches to empathy in applied human-centered work—and especially design thinking—but they have remained largely unquestioned. What is more, empathy has become an empty signifier, and empathizing is often a near-formulaic and pro-forma endeavor. To catalyze a reworking of the concept, in this paper I synthesize what has been said so far of empathy and its role in design and innovation, and I take stock of what these contributions point to. I ask: “How can we think of empathy as a scalar phenomenon and thus re-scale it in innovation?” I offer some illustrative, if unresolved, tensions with empathy I have had in my own ethnographic work with a robotics start-up, and I conclude the article with a series of provocations with the hope they will be taken up further.

Keywords: empathy, ethnography, design thinking, robotics

INTRODUCTION

Empathy has quickly become one of the most familiar buzz words in the world of business, whether in product design or human resources, customer research or in cross-functional team building. To invoke empathy in the contemporary professional setting is to signal “human-centered” and cutting edge. In recent years, since it was launched into the design and innovation professional vocabulary and then expanded to gain a foothold in both management and entrepreneurship milieus, empathy appears to have become not only a celebrated and desired tool into the innovation toolbox—almost a dispositif in a Foucauldian sense—but also so prominent that its invocation and application seems to have become mandatory. What was once a fresh reminder to business people, designers, and engineers that feelings, perspectives, and emotions, and not only numbers, have an immediate value to their operations and work, today appears to be fast becoming an empty signifier.

Our community is certainly not oblivious to this. As empathy´s celebratory potential began taking on formulaic and mandatory overtones, recent debates around it have offered an increasing array of counterarguments against the use of the term. In this catalyst paper, I do not aim to provide a single concluding vote to either of these camps, but rather to explore to what extent and with what effects could we, as a community of scholars-practitioners, rework the role of empathy in ethnographic research in applied settings. I synthesize what has been said so far of empathy and its role in design and innovation, and I take stock of what these contributions point to. More importantly, in so doing I am looking for clues as to whether there are paradoxes or unresolved tension in the ways empathy has been conceptualized and deployed in our practice which might provide a fresh analytical ground for asking new questions about empathy and how it is used in applied research.

What follows is a preliminary rewriting of the question of empathy. in the first, conceptual part of this paper, Synthesis, I ask: “How can we re-scale empathy in innovation?” As a first step in this endeavor, I suggest that to empathize is a scalar activity—a point whose implications and potentials are largely lost in both practice and writings on the topic.

My position here is animated by my own grappling with the topic, some theoretical, some stemming out of my 24-plus months of fieldwork with a radical innovation moonshot venture pursuing the development of humanoid robots, where I first started out researching questions of identity and team culture, and then became increasingly involved, through participant observation, into development and outreach questions of how to create empathy for robots at societal level. In Part II, Exegesis, I illustrate the limits of empathy in innovation and the study thereof as an example to such grappling.

However, such an understanding of the power and prominence of the affective dimensions of empathy requires that we understand empathy not on a flat scale, as a temporary adoption of a worldview perspective from a point-to-point individual-to-individual (as in a “the researcher” empathizing with “the user”). It requires, rather, a more granular understanding of empathy on a nested scale, one implicating historical, cultural, and social aspects in active interplay with each other, and empathy´s reconceptualization as an inhabiting of affective states and in terms of intermediary experience of the multiplicity of its constitutive affective variants (such as, among others, hope, anger, pain, passion, fear, exhaustion, bravery, weirdness, friction). Ultimately, it allows us to better capture, conceptualize, manipulate and responsibly account for questions of scaling feelings and perspectives in our work. In Part III, Catalysis, I suggest a non-exhaustive list of provocations that might help us reframe the question of empathy.

PART I: SYNTHESIS

Empathy´s meteoric rise to prominence in and dominance of the vocabulary and mindset of the world of design and innovation is part and parcel of the changes design thinking brought in the 1990s (e.g. Leonard and Rayport 1997). As one of the first and most distinct steps in design thinking—back then a novel approach on how to identify and solve problems—the rise of empathy as a concept and as a fundamental step in the innovation process in the last 20 years can easily be pointed to as one of the true success stories of a long-standing and continuously ongoing push for peopling engineering practice and management thinking. As a result, recent decades have seen a substantial number of professionals adopting it as their occupational identity and becoming empathy coaches, empathic strategists or empathy gurus, and entire dedicated “empathy labs” exist both as independent businesses and within large corporations such as Google and Facebook (Stinson 2020). In taking stock of the merits of empathy as part of design and innovation, as well as the challenges and dangers posed by its increasingly near-automatic and formulaic application lately, we must tack back and forth between not only what the term means and what it does, but also place it within a larger understanding and increasing critique of design thinking as the leading framework for innovation.

Originally starting as merely a new product development framework, but then steadily expanding into questions of customer centricity and organizational culture, design thinking practitioners lay claim to have a clear map of “applying the principles of design to how people work” (Kolko 2015; see also Kolko 2014; Brown 2009). The claim was that it created better outcomes, more finely attuned to user needs and “pain points” (Platzer 2018) than hitherto delivered by a remote bird´s-eye view of quantitative approaches. Part of its revolution has been to bring decision-making and product testing outside of the confines of labs and into the real world, placing the designer not only as a creator of specifications and aesthetics deduced from their own imaginary about the world in which their creations will be embedded and will circulate, but also as a validator and generator of real-life insights on how such a potential product would be experienced, and—crucially—understanding and placing the perspective of the user and the user´s reality above one´s own assumptions.

A key differentiator that design thinking claimed for itself in its approach was a kind of empathic perspective-taking that other approaches lacked, catapulting empathy—meaning “in feeling” from the Greek pathos via the German Einfühlung—as the go-to method of tapping into other people´s realities via sharing their inner experiences. What “being in feeling” meant produced a number of definitions, sometimes full of contradictions, which I am about to suggest, points to the weaknesses of adopting empathy as an approach – weaknesses which we should be either collectively moving away from, in favor of more ethnographic thinking, or working to eliminate and make stronger.

Thus, Battarbee et al. have defined empathy as “the ability to be aware of, understanding of, and sensitive to another person´s feelings and thoughts without having had the same experiences” (2014, 2 my emphasis), while a little later in the same text, they suggest and affirm practical approaches to achieving empathy precisely through experience-near techniques, such as, for example, to “participate in grueling endurance events to share athletes´ exhilaration and pain” (2014, 4), recalling to mind Lois Wacquant´s call for embodied methods, an “incarnate study of incarnation by practical example” (2014, 4).

Renowned product designer Jon Kolko describes it thus:

“empathy is about acquiring feelings. The goal is to feel what it´s like to be another person. That goal is kind of strange, because it´s unachievable. To feel what someone else feels, you would needs to actually become that person. You can approximate her feelings, so product research intended to built empathy is really trying to feel what other people feel. Assuming you aren´t actually an eighty-five year old woman, consider for a second what it feels like to be an eighty-five year old woman. This consideration is still analytical, it´s about understanding. You need to get closer to experiencing the same emotions that an eighty-five year old woman experiences, so you need to put yourself into the types of situations she encounters [to] approximate her feelings, leaving your own perspective in order to temporarily take on hers” (Kolko 2014,5)

Michael Ventura similarly notes, “empathy is about understanding. Empathy lets us see the world from other points of view and helps us form insights that can lead to new and better ways of thinking, being, and doing” (2018).

In sum, if one were to approach the concept of empathy as championed by design thinking (e.g. Brown 2009) and applied in marketing and leadership contexts (e.g. Ventura 2018) and product development (e.g. Kolko 2014), the promises that approaching the lived realities of those for whom we design, share moments of (cross) “cultural intimacy” (Herzfeld 2005), and for whom and with whom we ultimately create value are so many, that surely we should subscribe to deploying empathy without second thought. As described in these widely admired and popular approaches, empathy promises straightforward and surefire ways into other people´s realities and offers the ability to quickly and amenably tap into exactly the tranches that we need to understand for the purposes of delivering insight. Those applying empathy are implicitly portrayed as swiftly deploying it as a tool—although, unlike in ethnography, we never see this—a tool which works magically to translate the immanent and immaterial (feelings and lifewords) into the profitable, the material, and the immediate—objects, structures, services. As Jennifer Wong quips cheerfully (or ironically?) in an online article on creating empathic design systems, “…to help solve the UX process problem, inject a bit of empathy” (2019).

Whether it is presented as a tool from the designer´s toolbox (Kolko), as a mindset and a way of being (Ventura), or even perhaps as a medium to be administered (Wong), the one aspect which all proponents and interlocutors of empathy and design thinking agree on is depth: the prize is to understand “deeply” (e.g. Stinton 2020; Kolko 2014) and to achieve “perspective”, often seen as the product of “stepping in other people´s shoes.”

For anthropology, on the other hand, the question of accessing, understanding, and representing, in a formulaic shorthand, “how they feel in their shoes,” has never been a simple affair. The discipline has dealt with the question of fellow feeling as a vehicle to knowledge and as a subject of inquiry in a characteristically discerning manner. It has examined the question of “fellow feeling” (Solomon 1995), and has recognized a difference between empathy, emotion, and affect as three distinct domains, all of which require various levels of engagement with context, focus on embodied experience, and in which narrative and language mediate what is essentially an intersubjective experience that is both slipping, and yet firmly enmeshed, within social and political imperatives and structures (see, for example Lutz and White 1986; Besnier 1990; Beatty 2013; Beatty 2014 for comprehensive reviews; and on affect, Skoggard and Waterson 2015; Stodulka et al 2018; Newel et.al 2018). What is more, the ambiguities and limits of knowing “other people´s minds” has been shown to be always linguistically mediated (e.g. Keane 2008), but also necessarily embodied.

Thus both Daniel White (2017) and Danylin Rutherford (2016) have suggested that affect is largely unspoken and involves an embodied intensity of feeling which in turn gives rise to emotion within the subject. White succinctly captures the historical shift in the field between emotion and affect: “if anthropologists of emotion throughout the 1970s and 1980s had shown how feelings variously fix and stick through different compositions of language and discourse, anthropologists of affect shortly thereafter sought to show how some feelings slip, evade, and overflow capture” (2017, 175). In other words, if empathy is the ability to bridge inter-personal varieties of existence in the search for capturing meaning, it requires a reorienting of cognitive, affective, and bodily states.

Clifford Geertz´s famous skepticism as to whether adopting “the” native´s point of view is analytically valuable comes to mind here, as he argues instead for a “hopping back and forth between the whole perceived through the parts” (1983, 69). This is a subtly scalar proposition of engaging phenomena on a nested scale, and not a singular point-to-point one. Numerous other scholars have further unpacked the density of the concept. Famously, Renato Rosaldo´s poignant essay “Grief and a Headhunter´s Rage” (1993), on understanding murderous grief after the loss of a loved one only after the tragic death of his wife during fieldwork, suggests that there are domains of human experiences which are viscerally comprehensible only to those who have gone through them. More recently, and in a different vein, Douglas Hollan (2008)has argued that empathizing is an intersubjective act not only of feeling but also of imagination—and, crucially, is not the work only of the one empathizing but also requires a reciprocity of emotion and imagination on the part of the one being empathized with. This last point suggests that empathy is a perspective-taking exercise based not only on a singular agent, but is rather the product of two agents taking perspective with respect to each other—meeting on a mutually re-scaled perspectival plain. Finally, C. Jason Throop suggests that “empathy…must always be understood in the context of particular cultural meanings, beliefs, practices, and values…it is significant to explore how empathy is both recognized and enacted by individuals in its marked and unmarked forms but also to examine the specific contexts, times, and situations in which empathy is possible and valued and those in which it is not” (Throop 2010, 772; also Hollan and Throop 2008).

Yet “standing in their shoes” and “seeing like they are seeing” has been deemed increasingly deceptively formulaic.EPIC community members have already put forth a range of thoughtful objections to the preeminence of empathy discourse. Rachel Robinson and Penny Allen (2018), for example, have argued compellingly that empathy is not to be conflated with evidence, and have discussed the many traps in which they perceive empathy can introduce unwelcome and unhelpful bias. Tamura and colleagues (2015) have demonstrated that a “sense of ownership” is much more effective in the innovation and entrepreneurship context than empathy in that it creates more powerful research. John Payne (2016) has commented on Paul Bloom’s (2017) recent arguments against ‘empathy’ as a decision-making rationale. Payne carefully examines the limitations of empathy, noting: “Many of these methods have been repurposed from the social sciences to the needs of design practice. However, when removed from their theoretical foundations and optimized toward identification of user needs, they don’t account for the social implications of the work we do. This needs to change” (2016). Romain, Johnson, and Griffin (2014) have been similarly preoccupied with the ways in which empathy obscures the potentially meaningful to consider tensions between stakeholders in business. Finally, in an even more provocative vein, Thomas Wendt (2017) has argued that empathy is too human-centric, reductive in its Western anthropocentrism, thus essentially rendering the political aspects and questions of power in design essentially invisible, to the detriment of all.

In sum, for professional ethnographers, the way empathy is approached in most design thinking is problematic, stemming from an increasing tension between design thinking and ethnography. As Jay Hasbrouck has elegantly pointed out, design thinking has become “symbiotic in practice, but […] at odds empirically” (2018, 3) with ethnographic approaches, creating an unwelcome conflation between the kinds of questions that design thinking can ask and answer, and those that ethnographic thinking can, in addition to inaccurately framing all human-centric approaches as reductive.

But lest we consider that it is the anthropologists who are particularly critical of the concept of empathy, skepticism of it and its application has also been mounting in parallel in design circles. Without mincing words, Natascha Jen has spoken against it, calling design thinking as a whole “B.S.” for being too prescriptive, and signaling out empathy as specifically problematic: “the word empathy is prevalent in design discourse; people have become experts on design empathy. Back in the day we called it research…” (2018). And, in what is perhaps most damning condemnation because it comes from one of the most authoritative voices in design, Don Norman (2019) has admitted to not believing in empathic design for several reasons. One is because of the inherent inability to design for “many” by immersing yourself in the individual experiences of the one or the very few; another, because very often people´s own understandings of their own experiences and feelings are not immediately accessible to themselves. Finally, in his view, the ways empathy and human-centric design operate at present, they simply cannot solve for the truly wicked problems, such as climate change and hunger, for example—something that Natasha Iskander critiquesd in the pages of the Harvard Business Review as the inherent tendency in design thinking to protect the status quo and to reinforce the position of the designer, but not designed for—even if empathy is employed, because ‘solving for’ is the remit of the powerful (2018).

What emerges as a pattern, then, is that although empathy remains a fruitful, popular, and profitable approach to obtain perspectives and mine them for understandings of experience, its shortcomings are increasingly being exposed. Key among them are that it does not address its political potential and is regularly ahistorical; it does not lend itself readily to understanding contexts defined by uncertainty and complexity; it ignores key questions of the positioning of subjects—including in relation to each other; it can get lost in translation between research encounter and the production of an object. It does not make a critical distinction between reported experience and shared experience; and fails to explain how it deals with the limits of verbal explanation. Further, it does not differentiate critically between cognitive and affective empathy in a systematic manner, or explain when to use which variant. Nor does it address well how empathy operates from within the fraught entanglements of objective and subjective phenomena. Pain is one such phenomena, ironically enough. David Platzer (2018) has given the concept of “pain point” an excellent treatment. However, when the question of what the pain point means is refracted through a careful consideration of the role of empathy in it, it becomes necessary to situate both at multiple scales and levels of analysis: one objective (there is in many cases such a thing as real experience of physical pain, discomfort or unease which innovation addresses) and the subjective, more elusive forms of experiencing them—something which C. Jason Throop, not incidentally also thinking about pain, has termed “intermediary forms of experience”—“much of what we deem to be experience is characterized by … transitions, margins, fringes, by the barely graspable and yet still palpable transitive parts of the stream of consciousness that serve as the connective tissue between more clearly” (2009, 536).

In sum, although an inherently relational phenomenon, both in its reliance on accessing other people´s experiences and in translating them into different metaphysical forms (be they objects and services that circulate often locally and globally), current approaches to empathy fail to factor in something which anthropologists have long understood, examined, and theorized: emotions and affect are as social as they are cultural, and they are socially constructed, always enmeshed at the nested scales of individual and society, always rife with political potential, and always refracted through questions of meaning and power, always contextual, fleeting, incomplete, and elusive.

A good way forward, I believe, is to take a cue from anthropology’s insistence on unpacking what perspective is, and to think of perspectives precisely as scalar phenomena, and, in turn, scales as being a question of perspective and positioning. This is a running theme in both branches of approaches to empathy: the anthropological one and the design thinking one. In many ways, then, both anthropology and design rely first and foremost on taking perspective, which is an inherently scalar phenomenon, as a recent edited volume on the topic has proposed. Drawing on Marilyn Strathern´s definition of scale as “the organization of perspectives on objects of knowledge and enquiry” (2004, xiv in Summerson Carr and Lempert 2016, 5), E. Summerson Carr and Michael Lempert argue in the introduction to their edited volume on the pragmatics of scale that “scaling involves vantage points and the positioning of actors with respect to such vantage points means that there are no ideologically neutral scales [and that] scaling is process before it is product” (2016, 3-4).

Noting various examples of scale from a range of cognate disciplines, from distinctions between “private,” “personal” and “political” to “macro” and “micro,” and even conceptualizations such as “bench-to-bedside” throughout their introduction and the volume, a key motivation is to show “the inherently perspectival nature of scale, asking of our material “whose scale is it,” “what does this scale allow one to see and know” and “what does it achieve and for whom” (2016, 15, original emphasis). In a subsequent chapter, Susan Gal further highlights the comparative logic inherent in both scale and perspective: “scaling implies positioning and, hence, point of view: a perspective from which scales (modes of comparison) are constructed and from which aspects of the world are evaluated with respect to them” (Gal 2016, 91).

Yet in borrowing from anthropology, and re-scaling the process of perspective taking for business contexts in making it faster, less granular and less concerned with language, context, and embodiment as constitutive of empathy, design thinking has lost the kind of granularity that is exactly what makes empathizing a very rare kind of empirical tool for understanding other people´s realities.

Coupled, however, with the proliferation of the discourse of empathy in the business milieu, it would appear that two camps are forming. One is calling for more empathy—scaling it qualitatively and championing a more granular and extended research at the empathy step in the innovation process—and the other is signaling that the concept has ceased to be analytically useful. Where does that leave our field?

I propose that instead of seeking to substitute one´s own perspective for that of the user in attempting to gain perspective through a “like” state, a more ethnographically informed approach to gaining perspective would be to pursue a “with” state. Instead of “seeing like them,” “seeing with them” allows practitioners to position the otherwise wicked problem of capturing and representing others´ experiences in a granular manner by situating the empathizing endeavor at multiple scales at ones. In the next section, I offer two illustrations on the challenges for so doing, and in the final, catalyst section, I briefly touch upon what the opportunities might be if the field takes a turn in this direction.

PART II: EXEGESIS

Admittedly, the grapples that inform my provocations on the need to re-work the concept of empathy into more granular variants are borne out of work different to the commercial projects that are often presented here at EPIC, which focus on issues such as UX, product development, and organizational culture. Rather, the context of my (originally purely academic) work is extreme (cf. Hallgren, Rouleau, and de Rond 2018) in that it is unique and cannot be said to represent most commercial settings in which applied ethnography operates. Specifically, I work with a moonshot startup which dwells uneasily in the space between the commercial demands and expectations of the venturing scene and the scientific requirements and realities of research: an academic venture occupying the outer extreme edge of an already extreme category of innovation, which Sarasvathy (2008, 93) has termed “the suicide quadrant”—where a new product is introduced into a new market. In the case of humanoid robots, it is largely the case that the innovation is so radical, that there is no product, no urgent demand, and no immediate market. Traditionally, this has meant that either only large companies such as Google can afford to have in-house units (such as X, the Moonshot Factory) dealing with such kind of innovation, or that the government gets involved (cf. Mazzucatto 2011). In the case of my collaborators, neither of these were not the case—thus making product development and keeping the startup financially afloat a Herculean task. It faces the kind of slow diffusion and challenging scaling based not so much and exclusively on kind of innovation which does not rely on the quick diffusion cycles of lean driven product development but requiring the slow but steady interpretative understanding of how to disrupt meaning as a necessary early ingredient (Haines 2016).

Yet it is precisely this far-off vantage point that gives me a different vista on questions of how we approach empathy, affect, emotion, and experience more broadly in the search for useful understanding of others. This approach draws on the strengths and contributions of academic anthropology´s unpacking of these questions to which I referred in the previous section. But it also transforms questions from being meaningful and relevant into also being applicable and interventional. Applied ethnography makes such a pivot in its daily operations, which nonetheless do not preclude the ability to draw on and contribute to theory equally well. This point is worth insisting on given that we are still collectively working to end the “theory-practice apartheid” (Baba 2005).

I never intended to study questions of radical innovation, let alone musculoskeletal humanoid robots. Rather, as a scholar I was interested in how startup teams form in the academic context, and how their identities and practices inform team culture. But as I was studying questions of culture, identity, and practice within the setting of a moonshot startup in the academic setting, as is often the case with prolonged fieldwork, I became more and more incorporated into the team, slowly and over the course of many months, through our shared understanding that a sociocultural anthropologist has a legitimate role in a startup developing humanoid robots, especially where sociocultural outreach is concerned.

To be sure, no single paper could capture the multiplicity of angles through which the topic of empathy as a scalar and perspectival project, rather than as simply a method to gain perspective, is refracted in every milieu conceivable in innovation and entrepreneurship. In what follows, I offer two vignettes from my own ongoing work, which serve here to illustrate why I am compelled to question empathy in design thinking. The first instance revolves around questions of the robot´s features and appearance, and questions of gender and race in particular. The second vignette draws on how an unexpected failure of empathy resulted in developing one of the most popular pre-programmed function the robot has: hugging. In both instances, I chart the dilemmas that empathy, as a scalar, perspectival, embodied, and linguistic phenomenon, presents to our current thinking on the topic.

Cute, White, and Boyish? About a Roboy

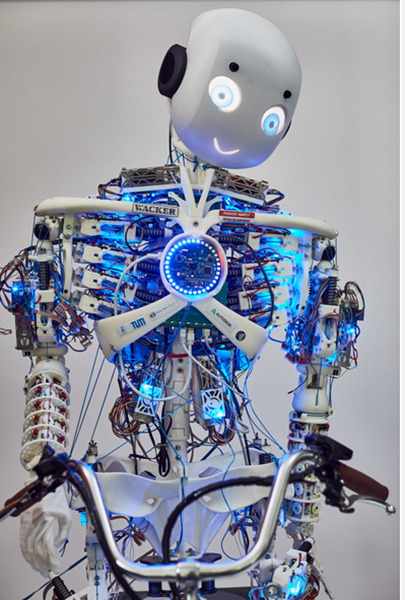

Robots are regularly evaluated on their utility: what they can do. This is true for industrial robots but also for humanoids, robots that attempt the visage and shape of human beings. The humanoid robot Roboy (fig.1) was conceived as a different kind of humanoid robot, not only because of the technological intricacy of developing the corpus of the body with a musculoskeletal mimetic engineering solution, but also notably because of the vision driving the robot´s development—a robot whose body is as good as a human’s—and its initial raison détre, a positive messenger of artificial intelligence.

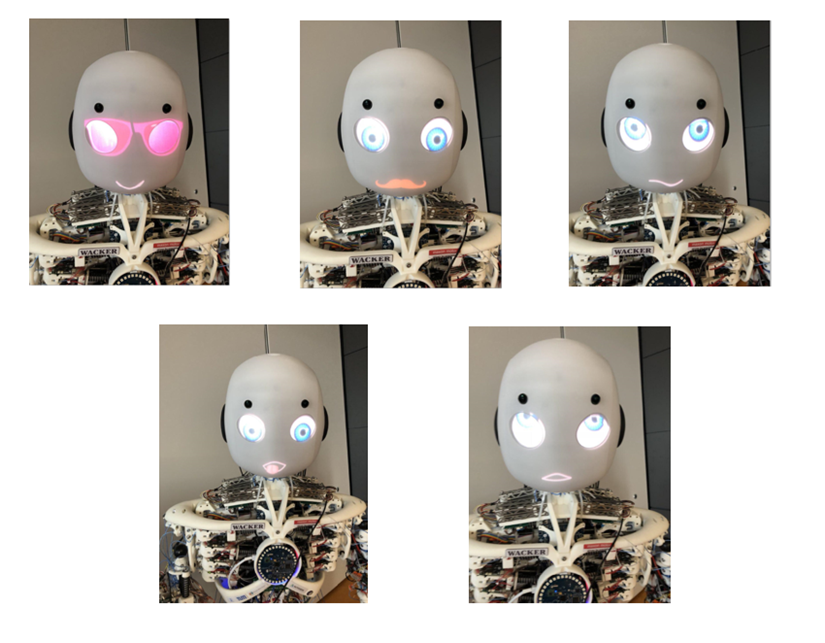

Roboy is not only a functional mechatronic system, however. With an extensive dialogue system, the robot can enter in conversation and display a number of emotions, such as smiling, winking, blushing, frowning and sadness (fig.2).

Fig. 1 Roboy 2.0 smiling interface © Devanthro –The Roboy Company. Used with permission.

My arrival at Roboy coincided with the unveiling of the second generation robot (fig. 1 and 2), Roboy 2.0, affectionately referred to as the “big brother” of the original robot developed at the University of Zurich, Roboy Junior.

Through a number of participant observations at international fairs and national and local events, which I attended largely to observe how such a unique team works and comes together at professional events, I nonetheless managed to document how the public interacts with both Junior (now forever retired) and 2.0. A key difference between them was that Junior was small, immoveable, and non-interactive, whereas 2.0 was a towering robot with a range of pre-programmed interactive facial expressions (fig. 4).

Fig. 2 Range of expressions on Roboy 2.0. Compilation. © Devanthro –The Roboy Company. Used with permission.

Again and again, people coming in contact with the robot made comments like “What can it do?,” “Why is it a boy?” and “How cute.” Only rarely, but importantly, did people make timid remarks about the robot such as “oh, it´s white.”

Important things in thinking about empathy in relation to the robot include how it scales in understanding how people react to a humanoid robot, how they would react if a particular feature was changed, and also how to make the robot empathetic in his interaction with people. The first one is not too surprising, given that the original meaning of the word ‘robot’ is rooted in the word for slave and that our collective understandings of robots continue to run along the lines of utility, as noted above. The question of the representation of gender and the emotional responses people have when interacting with the robot, however, as well as the remarks about color, are crucial here, because they bespeak a perspective according to which the robot is seen and interacted with. This is a perspective that the development team and the CEO must take into account, but which is not always easily integrated with the vision for the robot.

To say that people have to empathize with the robot so that it is accepted as a positive messenger for robotics and AI is too facile and belies the fact that people will empathize with it from their own particular perspectives and embodied experiences. For example, the question about the robot’s gender is overwhelmingly asked by women—a sign not only of the times we live in, in which female empowerment and representation is as under attack—but also of female members of the public working out a way to identify with the robot. Remarkably, the fact that while the robot is a “boy” and appears somewhat boyish his voice is female is almost always lost on the public.

At some events we have done together, the CEO somewhat peevishly explained that the robot was developed initially by “9 dudes in a lab at the University of Zurich” and that creating a fun near life size female figure—an over-sized doll, as it were—would have been not only weird but also inappropriate.

Similarly exasperating but fascinating are people’s comments on the color of the robot. Technically and literally, the robot is “off white”, a result of the standard material used in 3D printing. But the CEO has been asked many times to ‘correct’ this by making it whiter, and he has resisted. But while this off-white color could also be a wonderfully playful way of reaffirming the old semiotic axiom that because we are all different, we are all the same, this is not what the public wants or has seen. Rather, the question suggests that people tend to identify on a flat, literal, one-to-one scale, and that they are approaching the visage of the robot not only from a perspective of identifying with it, but also from within a larger contemporary culture that encourages personalizing everything. And the robot, in demanding that it has its own techno-selfhood, resists personalization.

Thus the robot presents a grand design thinking challenge in which empathy becomes fundamental in its perspectival and scalar dimensions, and where the question of empathy becomes anthropological in that it requires that you draw on knowledge of culture, context, and discourse, in addition to trying to step in the proverbial shoes. How do you build a humanoid robot with human features and make him a symbol of positive robotics if the identification and representational issues are not possible to integrate in a single design? If you want your robot to be human—in the universal sense of humanity—how do you make it particular enough to satisfy the immediate need for people to identify with it along gender and racial lines? Should the robot be personalizeable? How would that change how we collectively think about robots?

The question of the scales of the universal and the particular confound and escape the narrow logic of empathy as a state of changing perspectives with which we have come to grapple here. Urgent updates on the term are needed.

And in addition to that puzzle, there is the question of how cuteness scales. Cuteness is currently one of the most valuable propositions for the robot, seeing that the technology is so difficult to develop that there are no immediate markets yet. It is also a cornerstone concept around which one of the revenue streams of the robot revolves: the team regularly exhibits new technology being implemented in Roboy for sponsoring partners at international fairs.

One of the key challenges currently facing the team is how to scale the appearance of the robot so that it appeals to the widest possible public, not only in terms of race and gender, but also, given that its human-like expressive appearance is one of its key defining features, one which differentiates it from all other humanoid robots being developed. Cuteness is a property that children possess, but as the robot is advancing in generation and its range of manipulative abilities are further developed (currently Roboy can grasp but not walk yet), the question of its appeal moves more towards the center as pivotal to tackling questions of how acceptable musculoskeletal humanoid robotics will become in society in future. Scheduled to be unveiled some time in fall 2020, Roboy 3.0 will have morphed into yet another version of a humanoid robot. As the robot grows in functionality, should he age? Will the boy forever remain a boy? As a socio- cultural interface, one that is built to promote empathy between robots and humans and which relies on human empathy, these questions are as imminent for the team as they are wicked. They are questions that demand anthropological intervention in scaling meaning, above all: questions that require empathy at multiple scales, and going beyond singular use case scenarios and singular user understanding.

Hug by a Robot

The text comes at lunch time, saying that things at the international fair where the Roboy team is exhibiting with a partner, are going dismally. The engineers are underslept, disheartened, and “bored”, the sponsors are “concerned” and “unhappy,” and the public is passive and disengaged. This came on the heels of a really rough, pressure cooker week of development which overshot its very hard deadline, where emotion was high in the team, tempers flared up and stakes were mounting to deliver on a technical challenge that suddenly was not working out in the last moment, despite prior successful tests. That the fair was going down the drain is the last thing both the CEO and I wanted to hear: him as the leader and key responsible person, standing at the front of the booth with his corporate partners; me as the ethnographer who has been immersed in the team for some time now, working alongside people whose dedication and passion for their work I have come to admire and draw inspiration from myself. I know already that the team will emerge forever changed from the last week. Turbulence is not over, and this is unwelcome and worrisome news. I ask what the problem is.

Stuck in the midst of a tricky dance that anyone who has had to plan and execute an international fair exhibition knows: how to both fit in and differentiate your product at the same time with little budget, a partner signaling being underwhelmed, and a team who were working through the night to deliver against the odds, the CEO was facing an ostensible wall: “Basically, too many robots now. So just a Roboy is no longer enough.”

Thousands of miles away, back at my desk, I close my eyes and I try to imagine how it feels at these fairs that I have observed before, and what the team is going through right now. What works and what doesn’t. In my mind´s eye, I see the endless stream of only half interested people, whose glances you are trying to catch; the uncomfortable bumps of bodies around booths that have managed to gather attention, and the true awkwardness of sitting there with nobody in front of your booth. The scantily clad and heavily made up women selling robots at competitors´ booths and the giant culinary extravaganzas with free food and drinks. I can almost hear the myriad conversations surrounding a person at all times, sloshing into one giant wave of low murmuring sound. I can almost feel the stale air. In my mind´s eye, I can see the team, each and every one of them in the mood I have come to know well at fairs. One of them is so pure an engineer, and not at all a salesman, that he refused to see the value of going to these “boring as f***” events, where even the free food at other booths could not be tempting enough for him to justify why he is forced to stay there and not be back in his lab, “doing the real work, the work that matters”: developing. I see another member of the team, focused and razor sharp, doing what must be done, because in her words, this is her “life”, and this is her “family.” Always composed, she makes sure that the robot and its subsystems function as expected either directly or by delegation, but also keeps an eye out to ensure that the rest of the engineers are completing the necessary tasks. I see two of the more junior team members: one who is willingly suffering the many fast micro interactions with the steady stream of people with whom he is discussing the robot, and one who is responsible for stress within the team, having underestimated the amount of prep he needed to deliver a fundamental piece of tech—something for which he has tried to make up for by sleeping only two hours a day, and working the rest of the time. And I see Rafael, the CEO, continuously interfacing on behalf of his own company and on behalf of his sponsors, whose latest tech his robot is there to showcase. He is equally under pressure, from all sides, and trying to solve the problems typical of the remit of the CEO, which none of the other team members would face. I try to imagine how he feels and how they feel. Logically I can understand that he is bored, worried, and underslept, but at my air conditioned desk, having slept just fine while they were probably still programming and soldering at 3am in prep for the next day, I lack the visceral experience to relate.

I focus on how I first felt when I saw the robot at a fair and I tried to adopt the perspective of a bored engineer milling around from booth to booth, all fairly indistinguishable from one another. I remember I was intrigued but intimidated to touch it. It had wires exposed in the plastic exposed rib cage, perching usually on a bicycle or a pedestal, looking wobbly and ready to break at the smallest touch (something which rarely happens, and which the Roboy engineers routinely address by inviting people to physically interact with the robot, a prompt which does not work most times).

I try to think what unites these very different people, and of all the various feelings that this less-than-a-minute interaction foments. There is the curiosity of what it is, and why is the robot “so big.” The hesitation to ask, for fear of sounding stupid. The hot stale air pressing in a person, the unfresh bodies surrounding you. The odd discrepancy by the sheer tangle of obvious cables (perhaps a more daunting sight for non-engineers than engineers) and the wide blue-eyed winking face of the robot.

Tech. Engineering. Curiosity. The tinkering spirit. That is what unites them. So I type back after a while:

“organize a play session :)”. “use social media – #engineersatplay #fairsarenotboring #robotsarecool #flash #make #hack – to invite people who are bored as fuck by flyers and chicks to actually tinker with something. 1. Assuming tech crowd are full of engineers who are bored by the static and slow nature of everything and are [there] because [the location is fancy] and 2. [the partner] gets traffic. Social media gets clicks and likes, Roboy gets to surprise and stay agile. Nobody expects a guerilla hackathon at a buttoned up event.”

“hmmm,” comes back a text. “#robotsareboring I like, but then what´s the complement…#becomearobot? Bearobot. indefinitelife. Playforever. Exploreforever. So the play idea is excellent. I was already going in that direction”

A while later, another text comes, in the disorienting fashion of sudden text, when a person is plunged into the medias res of another person´s realities.

(Rafael) “they´re stoked. So good timing.”

(Lora) “who?” I ask. “How?”

(R) “team”

(L) “roboy?”

(R)“to try extreme measures. I´m bored.”

(L) “:)”

(R) “so I want to have fun”

(L) “play time”

(R) “yes”

(L) “guerilla hackathon.nobody expects”

(R)“yes.not as easy”

(L)“ohhh…keep me posted”

Later on that day, it turns out that Rafael had decided to stage a hug-a-robot demo instead, and the team was busy with coding in the necessary procedures. I check in on the next day in the afternoon, curious to hear how things were going at the booth: “hows it working? The strategy”

(R) “amazing. like no other”

(L) “really? Interesting. Send proof. I have very serious doubts.”

(R) “interesting”

(L) “you know why right?”

(R) “no”

(L) “because of the great threshold which usually exists, and that has been observed at fairs, on how to interact with Roboy…normally, people are terrified of precisely touch…unlike with Junior, there they usually touch either the hand or the face, because the robot is smaller and more childlike”

(R) “it´s even crazier. Roboy sits on a pedestal”

(L)“maybe you standing there, beautiful handwriting sign and winning smile in place, directing people to hug the robot works”

(R) “no roboy holds the sign of course”

(L) “so do they actually come and hug?”

(R)“yes”

(L) “interesting”

“who?”

(R) “all sorts of people”

(L) “women or men more? Age range? What do they say? Do they linger before they approach?”

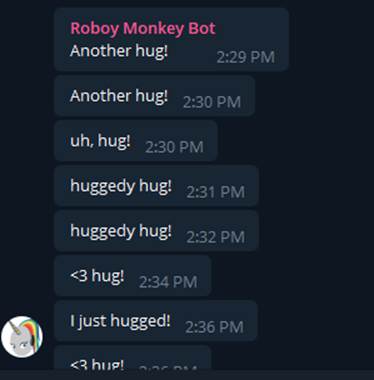

Soon thereafter, I find myself added to a specially programmed Telegram messenger channel, in which the robot is documenting the number of times he has hugged a human in real time (fig.3) “u even wanted proof” comes the half accusatory, half triumphant text by Rafael.

Fig. 3. Screenshot of real-time hug capture channel. Own capture from screen.

“of course,” I text back. “I am a scientist. about this of all things. *hugging* a *robot* and a public anonymous space. I want all the proof in the world. Because it will be very important—what do people say?”

Hugging, as it turned out, was so successful, that it became a cornerstone of every exhibition ever since, and a key marketing value proposition for booking the robot at fairs.

It is important to note here that had the CEO made a decision based on my empathy with the bored engineers in the audience (organize a hackathon), he would have gone in a misdirection, and in many ways, he made a decision rooted not in empathy – and fairly despite it. Although he reported that the audience, his team, and himself were bored, and although I gave a recommendation solving precisely for that, ultimately the decision to settle on hugs was drawn from larger sociocultural preoccupations on how to make robots social.

His decision, based not out of empathy with this team, but of a need to create empathy for the robot, managed to achieve both – in creating empathy for the robot in offering free robotic hugs, he also managed to rally his team, deliver value for his sponsors, and work towards culturally acceptable human-robot interactions. Although intuitively executed, in this case empathizing was placed within a nested scale of multiple converging relations – human-robot, public-team, team-manager, team-sponsors.

PART III: CATALYSIS

Traditionally, papers end. Conclusions rephrase what has been said until now, and tie up any loose ends. But this being a catalyst paper, the task here is to use the final stretch to ask myself, in the company of your patient attention this far, what it is that we should be catalyzing in the world of innovation, applied ethnography, humanoid robotics and AI, and scales; that is, the scales of disciplines and the scales of empathy. I have synthesized literature from both sides of the empathizing endeavor (anthropology and design thinking), and I have offered an illustration on how empathy has appeared in my work in the realm of robotics innovation. I have suggested that empathy is a scalar endeavor and that scales are perspectival in turn: to take a perspective is to re-scale, but that hardly ever involves a singular plain of action, but rather operates on nested logics. In lieu of concluding, however, instead of tidying this up, I would like to pick out and leave hanging loose ends for our community.

I do this via a series of intellectual provocations. These provocations are rooted not only in the synthesis and interpretation of the literature, both applied and theoretical, which I have offered. They draw not only on my musings of what empathy is, what it could be, what its limits are, and how can we rescale it, but also on the inevitable limits of my datasets and my experiences. These are questions that I cannot immediately take up, but I hope that we all collectively will.

One question to consider might be: what is lost and what is gained if the inquirer is always “on” emotionally in the pursuit of an empathic understanding? Do Malinowskian moments of un-grace, when we are impatient with our respondents, when we are at odds, or simply when we get them wrong or disagree profoundly with them illuminate situations and reveal additional dimensions of any particular situation which we are trying to understand? What extra dimensions of understanding does this add in the context of innovating from w human-centered perspective?.

What are the limits of empathy and can going against it have a positive outcome? In a broad vein, I have called for a move away from an attempt to achieve “like” states, or—at the very least—a healthy suspicion towards them. Yet, instead, could we conceive of empathy as a phenomenon dependent on spatio-temporal adjacencies – what I have called “with” states – those not of switched and temporarily replaced perspectives but as a space of motion oscillating comparatively between perspectives – a space of parallax as a process (Ballesteros 2015) as it were, not of perspectives as stable states, heeding Geertz´s call to “tack back and forth”?

Could we conceive of empathy as a space of negotiation and translation—embodied, linguistic, political and ethical—and how would that improve the ways in which we deliver actionable results?

What is lost in the lack of affective and evocative writing whenever the ethnographic account is replaced by the executive summary? In other words, when the ethnographic methods of taking perspective taking are decoupled from the painstaking explanation of the ethnographic account of how this came about in any particular human-centered encounter, how can empathy be accounted for? Alternatively, what new forms of ethnography, ones derived not from traditional fieldworks but from collaborative practices in a varieties of practical settings, can emerge in future?

How do we “take the perspective” of non-human actors or entities that nonetheless demand innovation´s attention: phenomena such as climate change or urban renewal, or robots and self-driving vehicles, as well as in context of interspecies relations?

Another question to consider as we move into more and more digital contexts is how we empathize in the digital realm. How is the lack of fully embodied experiences, otherwise so necessary to empathizing and gaining perspective providing a challenge for empathy in innovation, especially as we are, as of the time of this writing, continuously besieged by a raging pandemic which has forced an increasingly virtual online social interaction and life upon the world?

What is lost and what is gained in allowing for empathy to become a trend, and almost an ideology of innovation? How can we salvage from the trivializing hype the role of relating in our work?

What is the relationship between empathy and time? In the rapid contexts of business, how could empathy ever be achieved?

Finally, in going forward, how can design address the relationship of empathy and power, in acknowledging its interventional potential (Suchman 2011)? How will that help us deliver better insights to our customers, and help us create socially responsible businesses for the 21st century? Instead of attempting to see and feel and experience like, say, a black woman within an interview or even a day in order to create a product for her, one can, however, hire or collaborate with one—and in the space between these two perspectives, not only novelty but also ethics can be born.

I have suggested here that empathy is a scalar phenomenon, but that this aspect of it is inherently lost. The time is right to rework empathy not as a facile “standing in other people´s shoes” but as a negotiated, complex phenomenon of relating and of taking up positions, which are as political as they are experiential.

My final and most important point is that perhaps there is no need for designers to rescale the complexity of feeling for their purposes, and in the process lose precisely what makes ethnographic insight so powerful and valuable: its granularity and its ability to relate in embodied, situated, contextual ways.

Rather, designers should collaborate more with ethnographers—so we can have our empathy, and scale it too.

Lora V. Koycheva is a sociocultural anthropologist working on questions of innovation, entrepreneurship, and robotics in society. You can best contact her via Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lora-koycheva/

NOTES

Acknowledgements. would like to thank two anonymous peer reviewers and Erin Taylor for providing insightful comments in the continuous shaping of this work. Dawn Pankonien has been a patient and generous interlocutor for many months on the topic of intervening and empathy in general. I thank the students of my Cultural Analysis class for being critical about what empathy is and what exactly it does. Last but foremost, I am in debt to Rafael Hostettler, Alona Kharchenko, the Roboy Team, and Roboy 2.0 for adopting me as their anthropologist and teaching me the wonders of humanoid musculoskeletal robotics and moonshot venturing. I gratefully acknowledge the Joachim Herz Foundation´s support of my position at the Entrepreneurship Research Institute at the Technical University of Munich. I remain solely responsible for the content presented here, which does not represent my employer or the foundation

REFERENCES CITED

Ahmed, Sara. 2014. Cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Baba, Marietta. 2005. “To The End Of TheoryPractice ‘Apartheid’: Encountering The World.” In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings vol. 2005 (1): 205-217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-8918.2005.tb00023.x

Battarbee, Katja, Jane Fulton Suri, and Suzanne Gibbs Howard. 2014. “Empathy on the edge: scaling and sustaining a human-centered approach in the evolving practice of design.” IDEO. Accessed September 8, 2020. http://www. ideo. com/images/uploads/news/pdfs/Empathy_on_the_Edge. pdf.

Beatty, Andrew. 2013. “Current emotion research in anthropology: Reporting the field”. Emotion Review. 5(4), 414-422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913490045

————. 2014. “Anthropology and emotion”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 20(3), 545-563. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12114

Besnier, Niko. 1990. “Language and affect.” Annual review of anthropology, vol. 19(1): 419-451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.002223

Bloom, Paul. 2017. Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. Random House.

Brown, Tim. 2009. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation.[Kindle 2 version].” Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Gal, Susan. 2016. “Scale-making: Comparison and Perspective as Ideological Projects.” In Scale, edited by M. Lempert& E. Summerson Carr. University of California Press, Berkeley,91-111.

Geertz, Clifford. 1983. Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. Basic books.

Haines, Julia Katherine. 2016. “Meaningful Innovation: Ethnographic Potential in the Startup and Venture Capital Spheres.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. Vol. 2016 (1) https://doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2016.01084

Hasbrouck, Jay. 2017. Ethnographic thinking: From method to mindset. Routledge.

Hällgren, Markus, Linda Rouleau, and Mark De Rond. “A matter of life or death: How extreme context research matters for management and organization studies.” Academy of Management Annals vol. 12 (1): 111-153.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2005. Cultural intimacy: Social poetics in the nation-state. Psychology Press.

Hollan, Douglas, and C. Jason Throop. 2008. “Whatever happened to empathy?: Introduction.” Ethos 36 (4): 385-401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1352.2008.00023.x

Hollan, Douglas. 2008. “Being there: On the imaginative aspects of understanding others and being understood.” Ethos 36 (4): 475-489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1352.2008.00028.x

Iskander, Natasha. 2018. “Design thinking is fundamentally conservative and preserves the Status Quo.” Harvard Business Review 5.

Jen, Natasha. 2018. “Design Thinking is B.S.” https://www.fastcompany.com/90166804/design-thinking-is-b-s Last accessed September 27, 2020.

Keane, Webb. 2008. “Others, other minds, and others’ theories of other minds: An afterword on the psychology and politics of opacity claims.” Anthropological Quarterly 81(2): 473-482.

Kolko, Jon. 2015. “Design thinking comes of age.” Harvard Business Review 66-71.

————-.2014. Well-designed: How to use empathy to create products people love. Harvard Business Press.

Leonard, Dorothy, and Jeffrey F. Rayport. 1997. “Spark innovation through empathic design.” Harvard Business Review 75: 102-115.

Lempert, Michael., & E. Summerson Carr, 2016. “Scale: Discourse and dimensions of social life” In Scale. , edited by M. Lempert& E. Summerson Carr. University of California Press, Berkeley,

Lindholm, Charles. 2005. An anthropology of emotion. A companion to psychological anthropology: Modernity and psychocultural change, 30-47.

Lyon, M. L. 1995. “Missing emotion: The limitations of cultural constructionism in the study of

Emotion”. Cultural Anthropology 10(2), 244-263.

Lutz, Catherine., & Geoffrey White, 1986. “The anthropology of emotions.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 15(1), 405-436.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2011.The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths.

Norman, Don: Why I Don´t Believe in Empathic Design. https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/perspectives/leadership-insights/why-i-dont-believe-in-empathic-design-don-norman/

Payne, John. 2016. “What’s so Funny ‘Bout Peace, Love, and (Empathic) Understanding.” Retrieved September 10, 2018.

Platzer, David. 2018. “Regarding the pain of users: towards a genealogy of the “pain point”.” In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, vol. 2018 (1)301-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2018.01209

Roberston, Rachel and Penny Allen. 2018. “Empathy Is not Evidence: 4 Traps of Commodified Empathy.” In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, vol. 2018 (1) 104-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2018.01199

Romain, T., Johnson, T. P., & Griffin, M. (2014, October). On Empathy, and Not Feeling It. In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, pp. 181-182).

Rosaldo, Renato. 1993. “Introduction: Grief and a Headhunter´s Rage.” In Culture & truth: the remaking of social analysis: with a new introduction. Beacon Press.

Rutherford, Danilyn. 2016. “Affect theory and the empirical.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095843

Sarasvathy, Saras D. 2009. Effectuation: Elements of entrepreneurial expertise. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Skoggard, Ian, & Alisse Waterston 2015. “Introduction: toward an anthropology of affect and evocative ethnography.” In Anthropology of Consciousness, 26(2), 109-120.

Solomon, Robert C. 1995. A passion for justice: Emotions and the origins of the social contract. Rowman & Littlefield.

Stinson, Liz. 2020.”The Empathy economy is Booming, and There´s More at Stake than Just Our Feelings, Part 1 and Part 2.” Accessed September 27, 2020. https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/perspectives/social-impact/empathy-in-design-economy-good-bad-ugly/.

Stodulka, T., Selim, N., & Mattes, D. 2018. Affective scholarship: Doing anthropology with epistemic affects. Ethos, 46(4), 519-536.

Suchman, Lucy. 2011. “Anthropological relocations and the limits of design.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.041608.105640

Tamura, Hiroshi, Fumiko Ichikawa, and Yuki Uchida. 2015. “Goodbye Empathy, Hello Ownership: How Ethnography Really Functions in the Making of Entrepreneurs.” In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, vol. 2015 (1) 322-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2015.01058

Throop, C. Jason. 2009. “Intermediary varieties of experience.” In Ethnos, 74(4), 535-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840903202116

———————. 2010.”Latitudes of loss: On the vicissitudes of empathy.” American Ethnologist 37 (4): 771-782. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01284.x

Ventura, Michael. 2019. Applied empathy: The new language of leadership. Hachette UK, 2019.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2014. “Homines in extremis: What fighting scholars teach us about habitus.” In Body & Society 20(2): 3-17.

Wendt, Thomas. 2017. “Empathy as Faux Ethics.” Retrieved January 4, 2019 from https://www.epicpeople.org/empathy-faux-ethics

White, Daniel. 2017. “Affect: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology 32 (2):175-80. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca32.2.01

Wong, Jennifer. 2019. The How, and Why, of Creating an Empathetic Design System. Accessed September 27, 2020. https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/principles/design-systems/creating-empathetic-design-systems/.