Case Study—This case study highlights the value of taking clients through their own ethnographic encounters during a customer experience project. It demonstrates how taking key project stakeholders on fieldwork builds their empathy with their sales and service channels and end-customers, and creates a space for reflection and an imperative for action. The case study includes examples from ethnographic encounters and how they led clients to have a new understanding about the customer experience, and take action. It underlines the value of ethnography in business as not just uncovering insights, but as a process stakeholders should be involved in to lead to effective human-centered strategy and direction for a client organisation.

Keywords: Client experience, Customer experience, ethnography, strategy, automotive

ETHNOGRAPHIC ENCOUNTERS FOR STRATEGIC ACTION

A major US automotive company had recently boosted their sales considerably, but they had a problem. Their customer experience scores were low compared to their competitors. This was an indicator of wider faults which needed attention. They needed strategic direction to identify what was the cause of their problems, and to fix them.

Claro Partners won the contract to run this sixteen-week project in December 2014. Alongside their key client contact and project manager Veronica, who sat in the Customer Experience Insights department, they planned a set of activities to lead a selection of key stakeholders through a project to uncover qualitatively what was the customer’s journey through sales, use and service and to translate these into innovation opportunities and design some short and long-term solutions.

This case study will highlight the value of client ethnographic encounters in business consultancy, and share some key principles and practice to ensure these encounters are effective and successful.

(Due to client confidentiality restrictions the client is referred to as Engine Autos throughout this case study).

THE CLIENT CONTEXT

Engine Autos was ‘deeply siloed’ (Tett: 2015). There were departments competing with others, contradicting KPIs, the corporate office was working at odds with the dealerships, and there was a lack of direction because of larger structural changes at the top of the organisation, which meant employees lacked an overarching vision of what they were trying to achieve. There was great passion in the company to create changes, but individuals’ enthusiasm for change was impeded by legacy processes and the scale their operation. There were many different brands, with separate customer bases and heritages.

A few years earlier they had established a quantitative approach to tracking the customer experience. They adopted a ‘customer satisfaction survey’ which was sent out to every customer after a purchase or service visit. This came in the format of an online survey, or a phone interview. In an attempt to raise standards this survey had been elevated in importance. Salespeople and service people in the company needed high customer satisfaction scores to earn their bonuses. But this led to people playing the system. Customers were being told to rate their salespeople high, and it meant that scores were meaningless as indicators of the real customer experience. People with bad experiences wrote long hateful comments, others clicked through to award high marks across the board. Ironically the survey itself became the most heavily weighted moment in the customer’s sales or service experience. This process did not give the corporate office visibility into what was the real customer experience, and what were the specific areas that needed the most improvement, and they were frustrated. The existing reporting structure produced a lot of data, but not compelling actionable insight.

The stakeholders knew there would need to be changes to fix the processes that were creating poor customer experiences. They commissioned the project for a different approach to gathering insights about the customer experience. They valued that new narratives would emerge within the organisation by taking an ethnographic approach to assess their next actions. ‘An organisation culture capable of sustainable innovation requires cultural alignment, but to change an organisation’s culture, people must be motivated to think differently.’ (Rejon 2009: 164). The project approach was planned to link the insights from ongoing quantitative survey results to compelling ethnographic encounters, to create this motivation amongst the client stakeholders and wider organisation.

PROJECT APPROACH

The team’s approach set out to map the front-stage, what the customer experiences, and also the back-stage of the customer journey, the processes from the dealerships and corporate that support the customer journey. Both sides are critical as the organisational culture impacts the customer experience. The project was conceptualised to support the data from the surveys, to add a layer of narrative which would support senior management in reaching a point where organisational change would be compelling. Claro and Engine Autos agreed on four key deliverables.

- A 360° map of how customers experience corporate goals and measures,

- Illustrate the journey map with customers’ pains, challenges and delights,

- Strategic direction for how to improve the customer experience in alignment with, business objectives, both short term and long term, and

- Explore industry and retail best practices.

The team of one lead Partner, one Senior Associate and two Associates from Claro purposefully planned project activities that would challenge stakeholders to see their customers, and their own organisation, with fresh eyes. It was important that the project would provide them with experiences to see the impact of their day-to-day work on their customers and dealership staff.

The project adopted a classical anthropological approach that ‘makes the strange familiar, and the familiar strange.’. Social anthropologists from the academic tradition, such as the great Malinowski, pioneered long fieldwork expeditions. They travelled to far away places to do participant observation research, often returning with a greater understanding about themselves, not just the society they had been living in.

This project was conceived with that same mindset, to create experiences for stakeholders that would lead them to encounter another way of working and being, to reflect on their familiar, established modes of thinking and spark new ideas. As ethnographers working in a business and for a business, the team sought to translate the practice of a culture into a format understood by another. The emphasis was on making connections and patterns between what people say, and what they do, to take a holistic view that uncovers the contradictions in belief, action and narrative. The team set out to recreate the spirit of the ethnographic expedition, to deliver a client experience that would reveal insights about both the customers and their own company. The project sought to move corporate ethnography from being a research method to delivering insight with strategic corporate value (Depaula, et al: 2009:4). The project had an emphasis to design something new, not just observe and record the current experience.

The ethnographic approach to this project contained a variety of activities, and for the sake of orientation this article is organised along a ‘client experience journey’. The client journey included: pre-fieldwork, fieldwork – when the most significant ethnographic encounters occurred – and post-fieldwork.

PRE-FIELDWORK

Before any ethnographic fieldwork, researchers must prepare their research approach, their hypotheses and their equipment. Leading the client through these ethnographic expeditions also requires getting them prepared for going into the field.

Many of the project stakeholders, in sales, services, dealership training and marketing divisions had spent their entire careers in the auto industry, and winning over their confidence was initially challenging. It was important to answer questions and acknowledge early what outcomes they wanted from the project. From Barcelona, Spain, where Claro is based, the team ran ten stakeholder phone interviews with individuals or pairs of stakeholders. The department heads were able to get comfortable with the team, the project scope and the planned activities. During the calls they opened up in confidence about their challenges, and helped lay the groundwork for fieldwork focus areas. The team learned some of the specific terminology used within the company, and became familiar with their internal metaphors and department characteristics.

There was great emphasis put on making the outcomes of the project actionable. One member of the research team said, “I want to participate [in the project]. Measurement needs a context. The business reports just give numbers. We’re now looking at what does satisfy customers – not just metrics.”

In addition to these initial stakeholder interviews, the team received a mountain of documents from Engine Autos, including past projects, survey results and market trends. They delved into the data and extracted the most relevant information for the project. It was valuable to demonstrate they had understood the material they’d been given by the client.

The first face-to-face touchpoint with the stakeholders was the Kick-off workshop on a cold, snowy January morning at a log cabin restaurant off the side of a highway. Fifteen stakeholders arrived for this off-site, eager to discover more about what was planned, and how the project would deliver results they could act on.

At the one-day workshop the team from Claro Partners demonstrated they’d been absorbed in the client’s world, by running activities using the client’s existing frameworks and understanding of their customers. The team took everyone through empathy building exercises, to imagine what would be the emotional stages to buying a new vehicle, to prepare them for the fieldwork encounters that were to come.

This first interaction with the client required them to suspend their normal routine. The meeting was in an unfamiliar setting, and working alongside people from across different functional areas of the company. The stakeholders were challenged to take a holistic, customer-centric perspective, not an engineer’s measurement-focused approach. Another exercise centred around buying a new vehicle to force stakeholders to get into the customer mindset. It purposefully downplayed the financial factors, engine specifications and model customisations available to challenge how these stakeholders would otherwise characterise the purchase choice. The team also went into some detail about what would occur during research, and what role the clients would play if they were to participate in fieldwork.

Engine Autos understood that inspiration for strategic action does not necessarily come from monthly surveys. They felt the imperative to get close to their customers’ lives, to be absorbed in their world – it was to be a new experience for many of them, to actually meet their customers. There was excitement and nervousness about the encounters ahead.

FIELDWORK

Claro set the clients’ expectations for fieldwork early on. For the project to be effective it would be important to not just deliver insights from fieldwork, but also for Engine Autos to believe in the insights, feel a connection to the project process and feel ownership of the outcomes. It was commendable that ten of the twenty stakeholders were budgeted to go into the field and have their own ethnographic encounters.

The act of going into the field would allow the stakeholders to shape the direction of the research. By having them join, and have their own encounters with dealership staff and customers, their input would raise the quality of the research. They would be able to spot outlier behaviours, and add their industry knowledge in debrief discussions. An ethnographic approach to data gathering allows a team to balance focusing on the in-the-moment behaviours of people, and the longer term cultural changes (DePaula 2009:4).

As important as mentally preparing clients, there were also some practical steps to take. The clients were told to wear casual clothes for interviews, turn their phones off, travel with the team where possible, and arrive and leave customers’ homes at the same time as the interview team. The stakeholders joined their prospective teams for a pre-brief meeting, and during interviews had a role, whether that was setting up the video camera, taking photos, or taking written notes in their own notebooks.

Clients were expected to be fully involved in the interviews, and also the debrief sessions afterwards – they were to be para-ethnographers. An ethnographic encounter isn’t just an interaction with another type of person, it’s pulling out the insights and the synthesis as well. Fieldwork took place across three US cities; Jersey, Austin and Los Angeles, over the course of three weeks. In each location the team met with eight vehicle owners. They were a mix of customers, prospective customers, and competitors’ customers. They included people with a mix of ages, income levels, ethnicities and household setups. They also visited two dealerships to speak with sales people, finance managers, service writers and mechanics. Over the course of the three weeks, 10 stakeholders joined, for an average of two interviews each. The experience was an exercise in listening, observing and reflecting.

There were three occasions from this fieldwork that underscored the value of taking corporate clients through ethnographic encounters.

1. The Internet Sales Manager

There is a trend for shopping to increasingly happen online as well as offline, and for people to blend their search across multiple devices over a long period of time. Engine Autos had responded by updating their marketing efforts accordingly. They have state of the art brand websites for each of their vehicles. However once the seller has been on the brand site, they have to switch across to a local dealership website to arrange a visit or enquire about a particular vehicle. This is when the customer experience transfers from head office to dealer.

In Austin the team interviewed the Internet sales director at one dealership to understand his experience of the brand sites and customer expectations. Diego was a Hispanic man in his forties, he had been in his position for six months and he was revolutionising how his dealership was closing sales. Although the dealership management employed eight sales consultants working on the floor, Diego had control over all the leads that came through online channels, and twelve full-time Internet salespeople. He was running the websites and email communications for that location and for four other dealerships across the city. His access to potential leads was huge, far greater than the sales consultants stuck behind their desks waiting for walk-in interest or making cold calls.

Joining on this interview was Paul, who’s position at Engine Autos was in developing training. He was responsible for putting together the courses to train sales staff about how to close a sale, and knowledge of all the new vehicles. Diego’s desk was packed with paper, car posters and family pictures. For forty minutes he proudly demonstrated what he’d been doing to improve the user experience, and to fulfill orders as efficiently as possible. He was clearly profit focused, but also had energy for improving the customer experience as a whole. He referenced many different initiatives his team had taken.

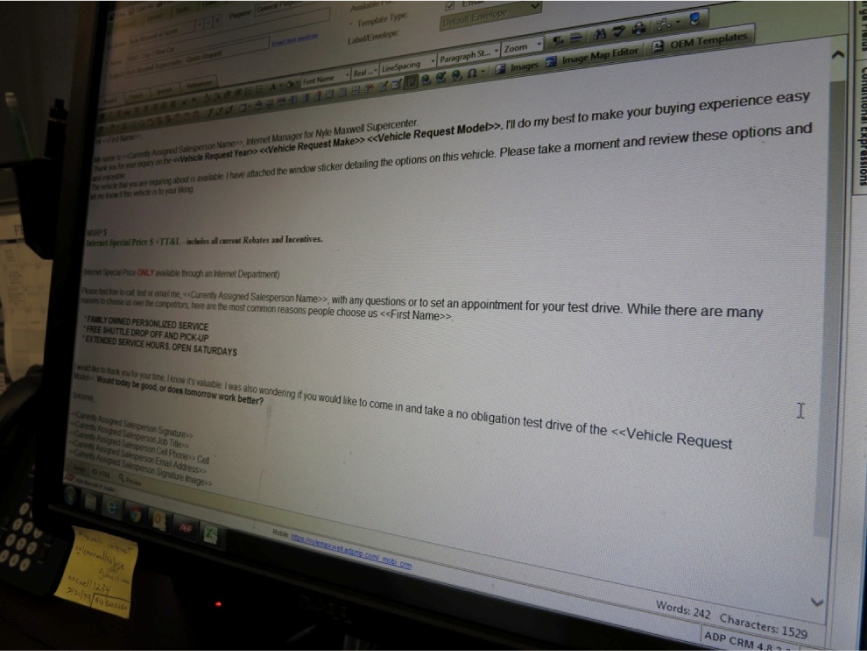

“We have a client concierge, which is basically a receptionist for the Internet department. So our customers have a secondary point of contact initially, and get them used to a very seamless handoff…. And get them familiar with our process and show them it’s seamless. So when they go to our finance department the transition is equally easy.”

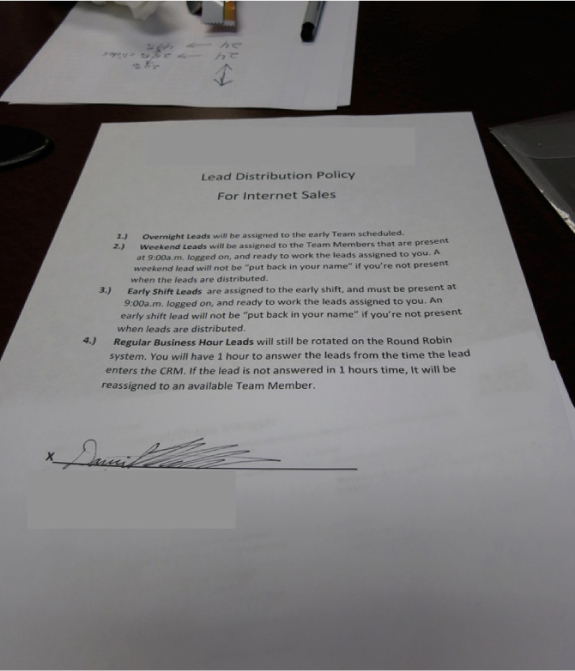

Another change was overhauling the banner images used in emails. People were reading emails on their phones, and therefore the slow to load large images were no longer optimised for this. He had overhauled the template for messages so that they were more personal. He had devised a system that was fair so that his sales team members were on a rotation to come in early to work so that they could pick up new leads that came in over night. His standards were high, for customers to receive an email reply in ten minutes, not three-four hours, which had been the norm before. All his sales consultants had a one-price model so that negotiations online were only for the trade-in price and the financing model for the new vehicle. He had initiated a system where every salesperson uploaded their email exchange to the company CRM system, so that if they would leave the company a record of their email correspondence was kept.

Paul asked Diego some specific questions, and was fascinated by how effective Diego’s Internet sales business was. He was copying a successful dealership in Idaho, which although in a remote location was making huge sales each month because of their Internet business. The encounter was a glimpse into the rapidly changing sales landscape. Paul’s job was to focus on training the sales consultants on the floor. What Diego was demonstrating was that this model is being eroded away by changing customer expectations and progressive dealerships that have adapted their offers accordingly.

The contract internet sales people sign

The email template the sales team use

Diego at his desk

2. The Confused Customers

How much a customer pays for their vehicle is neither consistent nor transparent. Dealerships buy their stock from the manufacturers, but then they are free to price their vehicles at whatever level they want. The industry has its logic for keeping this system from a supply chain management perspective, but an unintended consequence is customer distrust and aggravation.

One of the customers interviewed was Grace, a single woman living in a suburb of Austin. She was about to replace her existing 4×4. With two stakeholders in the interview alongside us, Grace showed us how she had been customising the vehicle on the Engine Autos brand website. She said at the moment she was configuring certain trims, features and colours – the price changed with every addition. She was enjoying that part. What frustrated her was she knew this would not correspond to the price that would be available when she would visit her local dealership. “I just want a price!” she exclaimed as she sat on the sofa and showed us her laptop screen. From the beginning of her customer journey, marketing was telling her one price, but she knew it would not be available. She would feel the need to negotiate with what the dealership would want to charge because she had seen a lower price before.

In a short video clip recorded at the end of the interview, she reasoned this isn’t a standard way to buy a piece of technology. You normally know the price. The need to haggle at the dealership was a hassle. She enjoyed the search in general, and building up her knowledge ready for the dealership, but this was in order to prepare herself for the sales tricks, “I know as much about the car as they’re going to tell me.”. She added, “Other than test-driving, there’s no other reason for going to the dealership.” The whole offline experience at the dealership was a necessary hurdle to pass, rather than anything else more positive.

One of the stakeholders that joined this interview was struck by how absurd it was for the customer experience to begin with a misalignment between brand and dealership, to knowingly create friction and anxiety, at a time when the customer should be falling in love with their choice. We had time and again heard salespeople share their frustration at having to explain the pricing system to irate, defensive customers who ‘simply wanted the price they saw online’. This encounter gave the stakeholder empathy with the customer as he could see the Engine Autos site itself was encouraging this kind of customer behavior. They were able to take the narrative of Grace’s experience into the next phase of the project.

Grace talking about her search

3. The Lemon

The newly appointed head of research at Engine Autos flew down to Austin to join the team for his first-ever ethnographic interviews. After a career as an engineer, he was coming to grips with research terminology, the rhythm of a day doing fieldwork, and interacting with customers for the first time. Alongside him, another stakeholder joined, a senior representative from Service, who normally worked managing the call centres.

Claro led a semi-structured interview with a man at his home about his service experience at a local dealerships. The three-hour interview was set up in a way to give the customer the opportunity to share his experience uninterrupted. There’s a power of sitting in a room and being forced to listen for a few hours. These stakeholders are often extremely time pressed, making multiple important decisions each day. The act of listening, absorbing and processing the customer’s experience should not be downplayed. This individual, Todd, had had quite an ordeal.

Todd shared his story of buying his car new in 2013. He noticed a few weeks later the cosmetic paneling on one side was coming off. He returned the car to the dealership where he’d bought it to be checked. They fixed it once, after thirty days at the service centre. But the problem reappeared. Three further times he had to take the car back. One time they took the car from him to get the work done, but when he returned ten days later to pick it up, they still hadn’t fixed it.

He explained, “Why are you doing the same thing over and over again. Wasting my time and your time…We waited for months and months for the parts to come in. And I said, why is it such a hard time to get the parts? We’ve ordered them four other times. They come in two to three weeks.”

The service department at the dealership blamed him for the problem, saying his driving had caused the fault to the side paneling. The dealership general manager was unsympathetic when Todd confronted him at the dealership.

“The last time I spoke to the service manager it just seemed like he didn’t care.”

He believed he had been sold a Lemon (a car which is defective from the factory), but Engine’s legal office was dragging out the process. They had not replied to his letter in over four months. He showed the team all the files with the evidence of his correspondence, and the lack of response.

After the interview, the two stakeholders raced into action. This encounter shook them. Todd’s experience had exposed poor customer service, disconnected communications among dealership staff, and between dealerships and the corporate office.

Their encounter in an ethnographic setting had made them aware not only of problems, but to empathically experience the emotional and financial impact that those problems were having on real customers, like Grace and Todd. They’d just been having coffee in this man’s living room, and his problem was now their problem.

Having stakeholders from corporate head office join for fieldwork gave them the stories they needed to articulate the importance of getting the customer experience right. They had rich narratives as inspiration for taking action within their organisation – they were emotionally invested in the project. The client experience journey was having its intended effects.

Todd shows the team his car

Rich (Claro Partners) talks through the service experience with Todd

POST-FIELDWORK

Ethnography was not merely fieldwork, and the synthesis process – translating rich narratives into insights and then opportunity areas for change – it involved much further work, and new kinds of encounters for the clients.

Synthesis was an ongoing process throughout the fieldwork. After each interview, the clients were involved in debrief sessions, reading through notes, pulling out key observations, and sharing if there were new ideas or questions for further investigation. The client’s presence was extremely helpful at this point. With in-depth knowledge of their own company, they were able to respond to assumptions, or answer technical questions about processes such as service recalls. It was valuable to understand how the clients made decisions, and what information was important to them.

After each week of fieldwork there was a conference call with all the stakeholders. The Claro team would share the project progress and initial insights, and provide time for stakeholders that had joined on fieldwork that week to share their encounters. This was important to reinforce the shared experience and the higher-level process the team was going through – suspending their normal mode of operating and thinking. It also firmly put stakeholders into the role of cultural translators. Big organisations need people to be able to interpret culture (Tett: 2015) so that new ideas can percolate to the most important decision makers from voices that are familiar. The process of having clients join on fieldwork and share their experiences is more effective than having outside consultants report back their findings at the end.

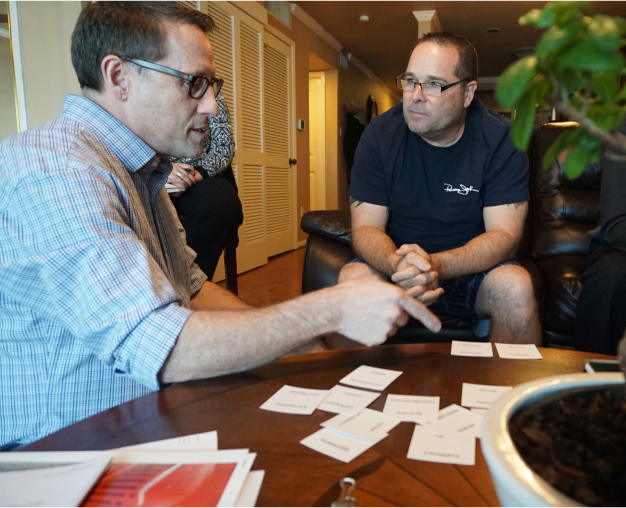

After returning from fieldwork in the three locations, there were just a few weeks to synthesise all the data to prepare for a co-creation workshop. Veronica the direct client, joined the team for one week of synthesis in Barcelona. There were structured work sessions to map out the key pain points, delights and then the prioritised areas to share back with the wider team to decide on action. Having Veronica join for synthesis was invaluable for understanding which issues should be prioritised, based not only on customer needs, but also the internal politics at the company.

The co-creation workshop was planned as an opportunity for all the stakeholders to align on what should be the customer experience pain points to address immediately – and time to plan how they could work across functional areas to fix the problems. This also was time to surface the issue that the company was not working toward an agreed vision. They knew they needed to raise their customer experience satisfaction survey scores – but they didn’t know what standard of experience they were aiming for.

In the workshop itself the clients had a moment of realisation. The experience of visiting customers, dealerships and highlighting the customer impact of internal misalignments had exposed some big gaps across the customer journey. It was significant that the outside consultants were not reporting back insights from research. Instead the group was discussing their different perspectives based on shared experiences and insights from fieldwork encounters.

The consultants and stakeholders ended the workshop in agreement on how to solve some specific critical pain points around announcing recalls and updating the status of service, as well as the issue of sales consultants in dealerships not completing their own sales until they had passed a certain training milestone. Working groups were formed to take further action. Significant as well, a majority of the key decision-makers were clearly onboard with the suggestion that the company needed a defined point of control over the customer experience.

CONCLUSION

This project emphasised the importance of inspiration from ethnographic encounters. The surveys, which were recording a version of customer experience, were not compelling employees to direct action. The rich experience of fieldwork – of encounters with dealership staff streamlining the online purchase experience, of customers purchasing a defective vehicle – had a powerful impact on the client organisation.

Over time the team’s recommendations gained traction and were being acted upon. Videos from fieldwork, of customers talking about their experiences, were incorporated into dealer training, and there was a philosophical change in this training, from a step-by-step process interacting with a customer, to meeting them where they are in the process. The customer experience survey was modified with efforts to improve the text analytics. Also some further quantitative research was carried out to investigate the frequency of the pain points that had been identified.

The client’s experience in this project had been purposefully crafted to be emotionally and intellectually involving. Taking clients through some best practices from fieldwork, going through the process of connecting an encounter to insights, and then re-designing the customer experience based on these insights was effective and powerful.

Clients’ memories of encounters they had will provide inspiration for action as they continue to work on the details of improving the customer experience. By elevating the experience of ethnographic encounters, Engine Autos gained new insight into their customers’ lives, and also their own organisation. The project created the impetus for change that will propel them forward in the future.

Josh Dresner is a consultant at Claro Partners. He has a background in social anthropology and has a Masters degree in anthropology and people-centered business from the University of Copenhagen. His past projects include: designing new product concepts in insurance, developing wearables data strategy for a global technology company and research for computer games design.

REFERENCES CITED

Cefkin, Melissa, ed. 2010. Ethnography and the Corporate Encounter: Reflections on Research in and of Corporations. New York: Berghahn Books.

Depaula R, Thomas S, Lang Z. 2009. ‘Taking the driver’s seat: Sustaining Critical Enquiry while becoming a legitimate corporate decision-maker’ EPIC Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/taking-the-drivers-seat-sustaining-critical-enquiry-while-becoming-a-legitimate-corporate-decision-maker

Jordan & Dalal. 2006. “Persuasive Encounters: Ethnography in the Corporation” in Field Methods. Vol 18 No4.

Jordan A. 1996. “Critical incident story creation and cultural formation in a self-directied work team” In Journal of Organizational Change Management.

Rejon J. 2009. “Showing the value of ethnography in business” EPIC Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/showing-the-value-of-ethnography-in-business/

Tett, G 2015. The Silo Effect: The peril of expertise and the promise of breaking down barriers. Simon & Schuster: London