This paper examines how ethnographic praxis as a means for driving social change via industry, went from a peripheral, experimental field, to a normalized part of innovation and product development – only to be coopted from within by a new language of power. Since the 1980s anthropologists have used their work to “make the world a better place,” by leveraging their tools of thick description and rich contextual knowledge to drive diversity and change within corporations and through their productions. As ethnography-as-method became separated from the field of Anthropology, it was opened to new collaborations with adjacent fields (from design, to HCI, to psychology, media studies, and so on). This “opening up” had a twofold effect, on the one hand it enabled greater “impact” (or influence) within institutions, but simultaneously subjected the field to cooptation. Recently, the practice of ethnography came to embrace the terminology of User Experience (UX) – though with it, ethnographers found what once made them distinct and differentiated (their representation of diversity of global cultures, the ability to think laterally with historically grounded theoretical approaches, etc.) was lost. UX, though a useful marketing tool, came to change the researchers and their productions, in subtle yet profound ways. This piece explores how what started out as a tool anthropologists hoped to use to shape the corporation, ultimately shaped them.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade the user and their experience has become of the utmost importance for the modern technology corporation. Throughout the multicolored corridors of low laying Silicon Valley office complexes, advocates to a new religion battled it out in conference rooms, cafes and faux tiki huts – UX they preached was to be our savior, a new philosophy of business practice and product development that, in a moment of economic crisis, promised to unlock profit while making the world a better place. A symbiosis of capitalist production and the understanding of everyday lives centered around product ‘use,’ this new language of power brought with it the potential for substantial shifts in the ways corporations imagined and acted upon the marketplace, changing both the organizations and their users relations to one another.

As the movement grew, an unexpected group came to be its priests. Ambassadors to what was otherwise seen by most corporate elites as an inaccessible world of mundane consumer lives (the consumer mind), an amalgamation of social science researchers and designers who had worked for years on the sidelines to reshape the corporation for the better, jumped at the chance to drive forward a seemingly new way of doing product and business innovation: “focus on the user first and all else will follow” (Google 2016). Though their day to day work looked much the same as it had during their past twenty years of industrial research and praxis, the value of this new language was all the more pressing in this moment – it seemed the corporation had found religion and was ready to be saved.1

Yet in the race to take hold of a user-centric future, the newfound clergy lost something. Many of the historical distinctions and subtleties of their respective disciplines became suddenly homogenized. Their boundaries were blurred and bleeding. Some believed the tearing down of old divides was for the best, opening new possibilities for collaboration and ideation. While others remained skeptical, wondering what had they given up by trading their languages of thick description, unique disciplinary methods, and long established epistemes for a new and seemingly vacuous term: user experience. The risk they worried, was that this new language of power they hoped to wield for change, would come to change them.

In this paper I take a moment to reflect upon and interrogate the rise of user experience as the new foundation for corporate technology innovation and organizational change. Drawing on my experience as a fledgling anthropologist cast into a Silicon Valley tech corporation at the zenith of an organizational transformation to become “user centric” I argue that in the race to take advantage of a popular language and newly receptive corporation, those researchers tasked with understanding and mapping the user in all its varying facets, attempted to imbue it with new meanings to make the corporation they worked within, and by proxy the world, “a better place.” Yet in their quest to make organizational change, they found their efforts placated by the very tools they hoped would drive change: the language of UX. Something once seen as potentially revolutionary; a force that could bridge the gap between the “science of ethnography” and the “practice of ethnographic product development” (Bezaitis 2009), UX in fact came to reshape their work from something that was transformational to something normalized and processual – a standardized business operation. Indeed what many anthropologists hoped to use to tame the corporation, ultimately tamed them and their ethnographic work.2

In this shift, user experience became not a tool for innovation, but one that perpetuated old practices of business-as-usual, becoming not a means of promoting fundamental innovation, but instead a new kind of language to re-frame processes of globalization – erasing historically situated terms of ethnographic analysis (e.g. production, consumption, colonization, inequality, race, class, religion, gender, etc.), and replacing it with a simplified binary (e.g. user and used). This reductionist language, though promising wide adoption through its generality, came to perpetuate many of the same pitfalls of global capital, but with a shiny new veneer. Indeed, in the quest to shape the corporation to meet the needs of people, UX became a new way through which to shape people to the needs of the corporation – causing tremendous moral and ethical tensions for the highly educated and reflexive class of professionals now tasked with advancing its cause.

THE RISE OF ETHNOGRAPHIC PRAXIS: AN ABRIDGED HISTORY

“Back Then”

To understand how the rise of UX represented a departure from earlier forms of ethnographic praxis in industry, we must look back at some of its history. EPIC remains a pivotal sight at which many of these origin stories are recounted in great detail, revealing the vast array of work anthropologists outside of the academy have accomplished over the years from scoping the possibilities of digitally collaborative work environments (Churchill 1998); to rethinking the practice and implementation of large healthcare systems (Darrouzet 2009); to mapping the future of the entrepreneur with socially distributed micro-jobs (Cefkin, Anya, and Moore 2014); to influencing the shape of a future of ubiquitous computing (Dourish and Bell 2011); to arguing for a more design-oriented ethnographic praxis (Salvador, Anderson, et al. 1999), to rethinking autonomous transportation (Brigitte and Wasson 2015), to driving more culturally sensitive corporations (Ortlieb 2010). As the list goes on, so too does our work continue to expand horizons and push theoretical and institutional boundaries. Though this paper cannot nearly capture all these stories, I hope to provide a least a few milestones that help paint a picture of the broad historical changes in our work that eventually merged it with UX.

Despite the sheer diversity of practices and contexts ethnographers have worked with over the years, their aspirations post-academy have kept a relatively consistent grounding in the idea of making ‘positive social change’ via praxis (Darrah 2016). As Blomberg recalled about her time at Xerox PARC in the 80s, “we were, back then, trying to understand how we could bring the social sciences into innovation in new [computer] technologies” (2015). Indeed the space at PARC was one imagined from the beginning as experimental, cutting edge, and on the frontiers of a new imaginary of computational futures. As Suchman describes,

PARC represented an investment in making technology futures. Deliberately placed far from Xerox’s corporate headquarters in Connecticut, the story goes, the research center was located on the west coast of the United States, in the nascent Silicon Valley, and charged with making a difference. In a topography mirroring earlier waves of westward expansion, PARC is positioned within this imaginary as a kind of advanced settlement on the frontier of the emerging markets of computing (2011).

This kind of frontier mindset allowed for a “critical distance” from the immediate demands of product development and a more open-ended exploration of topics related to emergent communication technologies, a distance that some of its founding members saw as essential for truly ‘breakthrough’ innovation (Suchman 2011). Though Xerox was principally interested in making photocopy machines, “for us PARC researchers, in sum, the photocopier could not be an object that was of interest in its own right; it was of interest only as a vehicle for the pursuit of other things.” (Suchman 2005; 387). From rethinking small scale behavioral interactions with machines to the organizational form of PARC itself, the breadth of work conducted over the years was expansive (Suchman 2011, Jordan 1997; Orr 1995).

Indeed the photocopier was a doorway through which to enter a role of influence over broader technological creation and advancement. The “other things” as Blomberg expanded, were in grappling with the material changes that emerged from shifts in communication technologies in the late 80s and 90s. What was once a focus exclusively on work practices of office employees and service technicians transmitting knowledge via communal stories about highly complex machines(Orr 1995), shifted – devices (such as the PC) were now being connected and used more and more by individuals with new interfaces, not just in professional settings, but all over the world.

At the time one of [our] motivations… was that these technologies were now being used, not just by engineers and the people who designed them, but also they were moving out into work places, schools, and everyday life… [These] technologies were becoming connected through local area networks and later through the internet and this meant that these were really becoming communication technologies. The kinds of perspectives that the social sciences could bring, in particular [ones] like anthropology, in helping us understand how these technologies would change the ways in which we interacted with one another [were essential] (Blomberg 2015).

What began as an effort to understand work practices of office employees, became a robust sub-discipline of Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), with broad reaching theoretical effects for the field of industrial ethnography at large. One central pillar that carried through from this was the idea of Situated Action (Suchman 1987), in which “action is understood as always unfolding in relation to the immediate situation at hand. This argument challenged the widely held view at the time that people plan their actions to achieve specific goals and then proceed to execute these plans” (Blomberg and Karasti 2013; 376). As ethnographic research showed time and time again, people are far more messy and unpredictable in their relationships to technologies than could be imagined by engineers in labs. Research and the design of interactive computing technologies could not be something static like, as originally envisioned, a “list of pre-meditated instructions” (Suchman and Blomberg 1999;394). Instead systems (like copiers, PCs, websites) and their interfaces (Mac OS, Linux and Windows) needed to be continually redesigned to engage in dynamic ways that were able to change to new contexts and interactions with diverse peoples in varying parts of the world. This was a unique insight at the time that holds true today – rather than training people to use machines, machines needed to be trained – remade with a kind of intelligence that allowed them to better map to the ever-changing needs of people.

Opening up Ethnography

Yet more “flexible workflows,” as Dourish aptly titled them (1996), were not the only thing that needed to be created to make machines more adaptable to people, indeed the very manner in which anthropologists did their work needed to change – from something individualistic and closed off to something participatory and open to the organizations in which they inhabited. Anthropology since its inception has been a highly individualistic, interpretive science – the quality and value of an ethnography often depends entirely on the subjective disposition of the ethnographer carrying out the research (Marcus 1996, Geertz 1973). It was (and continues to be) a particularly hard shift for the field when ethnography in many ways became divorced from “the anthropologist” as individual interpreter, reborn as something to be done in a collaborative, participatory way by “outsiders” (Bezaitis 1999). Indeed much of this ‘opening up’ was driven by researchers in adjacent fields using ethnographic methods to tackle the same kinds of problems as early PARC researchers.

Along the way we ran into some fellow travelers… a group of computer scientists in Scandinavia, and they were worrying about some of the same issues that we were, how were these new technologies going to change the way we work, and engage with each other, and in particular how were they going to change workplaces. And they had started to develop a series of techniques of involving workers in their design efforts, they didn’t quite have the notion of doing research, but they were directly engaging with users. And this then became part of our practice as well, not just incorporating our fellow researchers or folks in the business divisions…but also directly involving workers and other practitioners [into the research process] (Blomberg 2015).

From this early encounter with Scandinavian feminist design scholars (Suchman 1989; Star 1999; Markussen 1996; Baecker 1996; Bødker 2006; Baecker 1987), the field of Participatory Design grew alongside ethnography through the 90s and 2000s, showing how human-machine interfaces and systems must be innovated in an ongoing, iterative, and dynamic way that is open to collaborative processes with designers, social scientists, engineers and the like, directly involved. Indeed through these discussions, design became wedded as something essential to getting across ethnographic insights into products and business strategies, though the methods of communication to these newfound collaborators was not always clear (Suchman 2011). Blomberg again:

“We were experimenting at the time. There was no field like there is today back then. We were experimenting both practically and theoretically. We were doing things like creating video collages…space based prototypes…interaction analysis labs, the list could go on, but we were trying to figure out how do you do this, how do you bring the social sciences perspectives into design of [computer] technologies…and communicate [your findings] with other people who would be necessary….to have any impact on the innovations that were coming out of the research lab” (Blomberg 2015).

The “opening up” of what many viewed as the scientific endeavor of ethnography to a less formalized mode of product development (Bezaitis 2009), came with its own issues. Design is an inherently political, action-oriented field, while academic anthropology typically takes a position of non-interventionist observation. Participatory Design itself arose in response to the effects of computers in the workplace, dislocating and deskilling labor while giving more control to management (Kensing 1998; 169). Similarly then, the act of intervention into peoples lives is a political one, in the sense that designed technologies, infrastructures (Le Dantec 2013), and institutions, all shape the very relations of everyday lives in not so subtle of ways. From traffic jams, to waste, to government corruption (Lampland and Leigh Star 2009), to addiction (Schüll 2012), the actions of designers in molding the world around us to their visions, shape and channel people’s behaviors and lives in nearly every way in our built environment (Murphy 2016; Norman 2013).

The shift from “experimental” to “design” ethnography brought with it a double edged sword of political action. On the one hand the door was opened for greater incorporation into organizations and more influence to ‘make positive change happen’ (Darrah 2016), yet so too arose inherent ethical dilemmas about the nature of our work.

In this cauldron of experimentation that was going on, we had the opportunity to work with a young sociologist, Rick Robinson, who came to work with us on a project at Xerox PARC, it was a project with Steelcase. And after Rick left the Doblin group where he was at the time and founded eLab, with… John Cain, they began to incorporate some of the things Rick had learned…in the field of product design… and I think many of us have some kind of history or connection to eLab.

Indeed, capitalizing on a unique historical moment when the relevance of more individualized approaches to consumer and market research in industry were growing, eLab was one of the first overt attempts to wed design and ethnography together with the explicit mission of making “a better world by engaging with industry and commerce in the things that we create” (Blomberg 2015). As founder Rick Robinson pointed out during an interview, discussions at this time in business circles were around the need to create more individualized notions of consumers in order to maintain competitive relevance in product innovation.

There was a sense of being ‘invited in’3 at a point where, I think there was a recognition that understanding people was really critical to the success of an enterprise. You had gone through a period in the 1950s and 60s, when social research was stale, and the beginnings of quantitative sociology, using big chunks of data, came into popularity…then market segmentation models had really just hit their peak in the 70’s and 80’s [with profiles that said things like] yes, you too can make a lot of money off of who’s in “shotguns and pickups.”4

[In the 90’s] manufacturing started to think about how to do things that were more narrowly gauged to a particular kind of person…This is the era when “mass customization” was becoming popular…something tech was making possible. There was always a lot of discussion coming from the product design camp of being more differentiated, rather than monolithic, but it was not something that was sufficiently engaged with in a critical sense. An undercurrent of all this was [the sentiment] that surveys suck in making design decisions.

My hypothesis is that [for the business community, the idea was that] the more specifically we understand people, the more we can produce goods that they will want. This idea, led senior management and strategy people to look for other disciplines in the social sciences [for differentiation]. A lot of that sort of quantitative work, from demographics, to attitudes, to behavioral segmentation; the whole language of understanding consumers at that time was starting to blow up, because the tools for understanding it were much larger and much more flexible. More nuanced descriptions of different groups of people were starting to emerge, and…[businesses] needed to respond to that. That was where we [at eLab] decided to go. Rather than asking what should the strategy be, it was “how can we make what can be known useful?” (Robinson 2016)

Indeed eLab was able to gain a foothold of influence when more customizable manufacturing technologies, combined with new communication technologies, and emergent business trends towards individualization and cultural differentiation, created a need for new approaches to R&D. What was additionally unique about this group, as opposed to earlier iterations of ethnographic praxis in industry, was their very forward idea of using social science research to direct design outputs, and by proxy corporate strategy and products. As managing partner Maria Bezaitis recounted:

Our work was firmly rooted in a vision for how research could shape design…in a joint partnership. From that very specific motivation and agenda we evolved points of view about product development and broader views about business innovation…eLab remains the only firm to have demonstrated how strong ethnographic research, with its own dedicated outputs, could provide a basis for design.

At the time this was a groundbreaking approach. Design as a field of practice before this moment tended to be “‘self contained’…it doesn’t really want to do anything with anyone else and so [even today] in its marketing (e.g. “design thinking”) it takes up more and more space, refusing to let itself be directed by anything outside of what it speaks for” (2016). Partnering ethnographic research and design then, not only opened possibilities for broader collaboration between the two fields once closed to eachother, it provided a path towards more directly shaping corporate outputs with social science theory and methods. Indeed for these researchers, “we had an underlying political kind of motivation for what we were doing,” that made them distinct from doing purely exploratory or experimental work (Wolf 2016).

The “politics” of our work [was and continues to be]…tied to fundamentally changing how corporations conceive of and get things made, changing the assumptions that frame value to corporations and to the business leaders that are accountable for overseeing how those assumptions transform into products/services/technologies. eLab demonstrated what was possible with design. (Bezaitis 2016)

Indeed, rather than shy away from projects that shaped the world they took them head on, grappling with the same “[ethnical] issues we still confront today… issues around de-skilling, job losses, and in who’s interest did we serve” (Blomberg 2015). One example of this kind of project work given by Robinson had to do with a dilemma of low-wage worker representation and the organization of the kitchen at a large fast food chain.

The problem was framed as, one of their core products was consistently being spoiled by minimum wage workers, not understanding what the steps were they should go through…They had this horribly dehumanizing language [for the employees]… Their initial request was to redesign the manual that they used in training… [but instead we used] this idea of “chunking” taken from cognitive science, and laying that into the physical space [of the kitchen].

We didn’t have embodied interaction5 as a language at the time…but it was the same thing…The work that we did enabled us to offer them a different way to think about the relationship between steps in a task and where the information was displayed – where it was available [throughout the kitchen at each step].

The discussion went from ‘you have to remember it all’ to ‘is the information available’ (when you take the food out of a freezer, or put it into the fryer, etc.). It was an enormous success…and it enabled the corporation to stop treating their workers like, “oh my god they can’t remember fucking lists.” I take my daughter into those restaurants now, and say ‘see – John and I did that.’ (Robinson 2016)

In this case, the joint role of design and ethnography played a direct hand in not only shaping the built environment of the fast food chain, but also the relationship between management and employees within the organization. The example revealed the kind of political power this hybrid method held at making very real, socially informed change happen within corporations.

One of the early innovations of eLab for driving this kind of corporate change, still in use today, was the idea of “experience models” or frameworks. These were created by “breaking down an experience and visually communicating its key elements” in an immediately understandable and easily translatable model (Morris 2001). These models became “a commoditized part of the work ethnographers [were] expected to do, produced across projects as 2×2 matrices, maps of concentric circles, [and] discussions of behavioral modes” (Bezaitis 2009). They were used, on the one hand to better communicate patterns of human behavior to product teams simply, but moreover as an explicit way of incorporating social science theory into corporate outputs (Robinson 2010).

As Cohen discusses, “In a design setting, especially one where design research is common, theory and method (that is, our ideas about the world and our techniques for arriving at those ideas) will come to exist and circulate materially; they become, quite literally, embodied in products and made public” (Cohen 2005; 2). Shaping products then became the direct means by which practitioners viewed their ability to make interventions in the human condition and social organization, through the material embodiment of social and cultural theory in everyday objects of use.

From Periphery to Center (and Back Again)

In the 2000s, the methods anthropologists had originally experimented with, were becoming a more and more common practice within corporate innovation work. The time when social scientists worked purely as exploratory academics within varying labs and think tanks in Silicon Valley, was coming to an end. Indeed with their work, ethnography began to go from something peripheral, experimental, and exotic, to something normalized within the logics of product development. As communications technologies grew in their pervasiveness, mobility, integration – and the internet continued its advancement towards a ubiquitous utility and primary vehicle for organizing large swaths of information, knowledge, and technosociety (Woodhouse 2013) – anthropologists and ethnographers became ever more central to deciphering the complexities of global flows (Appadurai 1996) and human behavior for corporate elites. Researchers were recruited over the decade to shape ethnographically informed practices at historically influential technology companies – IBM, Intel, Microsoft, Apple – as well as newer ones – Google and Facebook – and at consultancies both emergent and established – IDEO, ReD, Gemic, Stripe, Claro, and Gravity Tank, to name a few. Indeed, “in the past twenty years, ethnographic research has moved from a tiny differentiating tool to broad acceptance” (Robinson 2010).

A major example of this growth in “making ethnography matter,” was the work done by the Peoples and Practices Research Group, and iterations thereof, at Intel. As part of the company’s R&D division, a “small handful of people…through patience, persistence and a fair amount of invisibility, managed over a decade to change the company in a number of ways. This is no small feat,” to go from what was once an experiment to a central force in organizational advancement and change (Bezaitis 2009; 7). This group, which consisted of researchers from, “psychology, design, cultural studies, media art, computer science, public policy and of course anthropology” (8) was home to several founders of EPIC – and managed to take what had become at this point the immutable wedding of ethnography and design, and apply it directly to product and business groups. By the end of the 2000s, central figures of the group, Genevieve Bell, Tony Salvador and John Sherry, were making strides to “grow and run local ethnographic teams [directly] tied to the product interests of…business groups” (7).

However, despite the overall growth of the field, periods of collapse and reorganization that mirrored broader economic downturns (in the late 90s and 2010s) of these pioneering institutions (like Xerox PARC and later Intel Labs), left many practitioners with a dilemma of legitimacy. The academics were fractured – some went back to the academy (Suchman 2011) finding new homes often outside of anthropology in Informatics, Science and Technology Studies, Human Computer Interaction6 and others – while those who remained were remade as expert consultants to pioneer their new methods in corporate organelles which had limited understanding of their value (Madsbjerg 2014). Over the years, and many hard political battles fought, this community stitched together shifting languages of power to translate the value of their work to diverse audiences while attempting to maintain core aspects of their respective disciplines. These languages, like the institutions they inhabited, were too in a state of flux (Anderson 2011; Salvador et al. 2013), ever-changing in their descriptions and justifications of what they did. As co-founder of EPIC Tracy Lovejoy recalls about this period at Microsoft,

I remember in the early 2000s there was a belief that anthropology would be deeply rooted within business by this point. At Microsoft, ethnographic specific roles have really struggled to take root, despite starting to employ practitioners around that time. Rather ethnography still remains a method that can be claimed by anyone with research training. In part this is because there is no clear way to fit an “ethnographer” into the full product cycle. Someone who specializes in deeply examining the broad questions that help uncover new opportunities or rethink an existing product may not have a clear role as the product moves out of conceptualization and into iteration and execution. So many of us adopted the title of UX Researcher or Design Researcher and geeked out during the moments we could focus on qualitative work, then used our skills to answer a different set of questions with different methods for the remainder of the product cycle, always on the lookout for a question that would allow us to get back into the field [of ethnographic praxis] (Cotton et al. 2015).

In trying to establish their value in new domains, anthropologists began to describe themselves with a host of pseudonyms, meanwhile non-trained researchers also claimed to do ethnography – diluting the field (Lombardi 2009; Nafus and Anderson 2006; Flynn 2011). From design thinking/research, to iterative design, participatory design and publics (Le Dantec 2013); to Human Computer Interaction (HCI), to human centered design, to human factors engineering, to agile, to behavioral engineering, to behavioral psychology, to sociology, to big data, and so on, ethnographers languages of translation evolved alongside changing loci of value in the corporation, often stretching thin their core principles and the kinds of work done.

Knorr-Cetina (2009) would describe this increasingly diverse clustering of semi-related fields and languages of power, or “amalgams of arrangements and mechanisms – bonded through affinity, necessity and historical coincidence,” as an Epistemic Culture, “which, in a given field, make up how we know what we know [as truth]” (12). The rise of an epistemic culture is gradual, and reflects a common theme in exploratory scientific research. As Susan Leigh Star describes,

“most scientific work is conducted by extremely diverse groups of actors. Simply put, scientific work is heterogeneous. At the same time science work requires cooperation – to create common understandings, to ensure reliability across domains, and to gather information, which retains its integrity across time, space, and local contingencies…scientists have made headway in standardizing the interfaces between different worlds…by reaching agreements about methods, different participating worlds establish protocols, which go beyond mere trading across unjointed world boundaries. They begin to devise a common coin, which makes possible new kinds of joint endeavors” (1999;10).

In industrial research environments the path towards creating this common coin was compounded by the structural characteristics of the corporation. Researchers in teams across the valley had forged new relationships, gaining substantial footholds in their quest to realize value in ethnographic praxis as a means for innovation, but still faced escalating pressures of legitimacy as they became further normalized in uncharted territories outside of experimental labs. As their work was no longer shielded from industrial shifts – it now became more directly subject to the whims of corporate hype cycles and cultures, pockets of which still viewed the field as experimental and novel, rather than central to product development and innovation. Indeed, the ongoing process of educating otherwise naïve stakeholders of the value of their research, often compounded anthropologists feelings of being out of place, when they found their efforts to “make the world a better place” sidelined due to a lack of understanding from new colleagues (Blomberg 2015).

UX ON THE SCENE

One such move to further advance and normalize ethnography as a cornerstone of corporate product development and innovation, was the adoption of User Experience. This field, which seemed to promise the tools of translation necessary to advance the goals of Anthropologists ‘to make positive change,’ in many ways came to stifle them – eliding the very thing that made ethnography distinct to begin with – its contextual richness and representation of cultural diversity.

The concept of the user is nothing new for anthropologists working in Silicon Valley. The term has been prevalent in engineering and technology circles for decades, gaining increasing popularity since the Engelbart demo at the Stanford Research Institute in 1968 on the future of human computer interaction (Lanier 2010). Even at PARC in the 80s, anthropologists were working to get away from the term’s entrenchment in engineering circles: “we were, way back then, very much concerned with not using the word user, because we were interested in things way beyond the ways in which people interacted with technology, we were interested in them as workers and practitioners, so we began to talk about them as practitioners, not users.” (Blomberg 2015).

Though the user has been in play in industry circles for some time, the coupling of the word with experience in UX, is a more recent phenomena. One of the first papers to use the phrase “user experience” came out of Apple in the early 90s from an interdisciplinary team of social scientists working to “empower everyday people with choices via products designed for people (a kind of everyday anthropology).” As Anderson elaborated “we were doing something very different from Xerox, they were all about “work” and “organizations” and we were about “users” and “innovation”…Rick [at eLab] sat in the middle” (Anderson 2016). The paper co-authored with Norman and Miller (Norman and Miller 1995), was a kind of vision statement defining the term as “all aspects of the end-user interactions with a company, its products and services” (Nielson and Norman Group 2015). Yet corporate cultures of the time, combined with the term’s inherent vagueness, kept it largely unengaged publicly as a general means of describing research practices for nearly a decade.

But UX received a substantial boon when, in 2007, Steve Jobs stood in front of millions around the world, announcing the iPhone as the next great leap in personal computing. In this speech, he christened “the user” and the betterment of their experience (or UX) as the pivotal focus for the next era of technology production (Jobs 2007). This idea was not new, and had in fact been brewing in pockets of the valley for decades among social scientists, designers, and engineers – but what Jobs did this this moment was unique. Drawing on the growing popularity in business circles of conceptions of the economy as “experiential” (Pine and Gilmore 2011), and discussions in technology circles of the importance of the user, he placed the emergent field of UX at the center of the future imaginary of technology for the first time.7 Ethnography, by now nested in the whims of product development, became swept up in the hype.

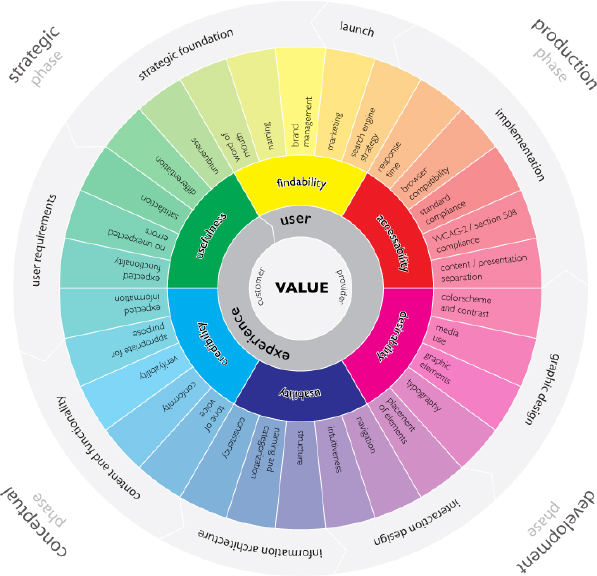

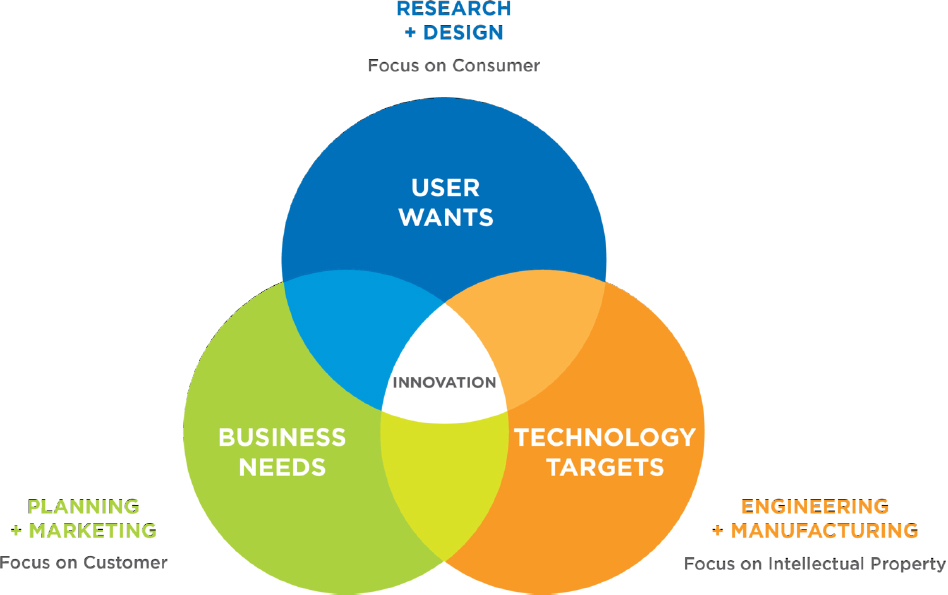

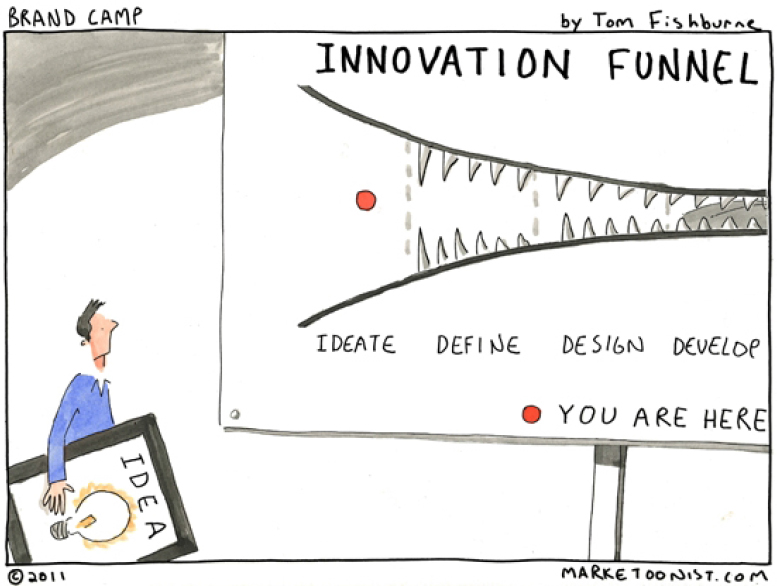

Seen as a “breakthrough innovation,” corporations in the valley began to respond directly to the new language of UX. Departments were created. Job titles were invented (Cotton et al. 2015) A multitude of new models for the innovation pipeline were imagined and enacted – personas, user journeys, mental models, experience maps – with the user at the center (See Figures 1 & 2; Payne 2014). It seemed the community of practice had found a silver bullet of sorts for their uphill battles – a brand that loosely described their work, acting as a ‘foot in the door,’ but also holding the “revolutionary potential” to transform organizations and their productions to be ‘people centric.’ Some speculated this movement was a paradigm shift (Khun 2012, Yocco 2015), bringing with it new ways of thinking, while others contended it was no more than smoke and mirrors – a new face on an old practice (Mazzarella 2003; Flynn and Lovejoy 2008). In the quest for legitimacy, and the rush to adopt a now popular term, the ethnographic praxis community hoped they might gain ground in the present, imbuing the new yet empty language of power with their own meanings in the future.

Figure 1. The Business, User, Technology or BUT model of innovation.

Figure 1. The Business, User, Technology or BUT model of innovation.

Figure 2. The innovation pipeline model.

Figure 2. The innovation pipeline model.

Yet a major issue with adopting UX as a vehicle of change, was that it acted more as an empty brand than a theoretically centered discipline of research and study. Quickly after its ascent, competing definitions arose, making it hard for the free floating signifier to gain a substantial center. From “the overall experience of a person using a product such as a website or computer application, especially in terms of how easy or pleasing it is to use” (Kuniavsky 2003), to “a person’s entire experience using a particular product, system or service” (Law 2008), to “the experience the product creates for the people who use it in the real world” (Garett 2010; 6), each definition retained a few core elements, but lacked a theoretical center. Last year at EPIC even, researchers were still working to define the field:

“User experience” …is human-centered and is the co-creation of an interaction between a person or persons and an artifact. User experience includes usability and all aspects a user encounters when dealing with a product or service from the branding to the motion and audio design to customer support. It is about how the product or service makes the user feel and encompasses both user behavior and the social context of the user-artifact relationship” (Baxter 2015).

The key scaffolding of the definition lies largely in a causal relationship between three objects, the “user” or “person,” and the subjective “experience” of said person in relation to a “product” or “company.” Though the qualifiers in each definition may change, the dualistic and circular setup between the binary of use and used remains consistent throughout. However, each of its components are so absolutely divergent of one another in their epistemic, philosophical, cultural and material origins that the term is left hollow. As one UXer described, “it’s as if one was to call themselves a ‘fundamentalist atheist,’ the logic of the term does not go far beyond the structure of its very phrasing” (Interview Archives, CD 2012). The answer to the question ‘what is user experience?’ can offer little more than the name itself, ‘a user’s experience.’ Cohen examined the logic of this phenomena at EPIC back in 2005. “It goes a little something like this:

study users of X in order to understand the phenomenon of X, where we can replace X with “mobile phones” or “toothbrushes” or “SUVs” or “Internet-based investment banking tools.” We identify a thing that we want to study, then look for “users” of that thing. This is common in design research as well as in studies of technology more generally, whether conducted in universities or companies…Another assumption—in some ways far more problematic—is that users of X are the only people who can tell us about the social life of X. If homeless women are not “users” (and the first assumption has it that they are not), if for instance they use Ys rather than Xs, then they are the wrong people to study, especially if what you want to design are improved Xs (3).

What seemed like a brand that anthropologists could use to gain traction in the corporation, began to fundamentally alter the way in which research problems were framed and solved for in a subtle way.8 Rather than looking at how people live in the “real world,” with ethnographically informed theory and practice – as subjects of the state, colonization or capitalist expansion; gendered, raced, and classed bodies; or spiritual/religious ideologues (Scott 1998; Anderson 2006; Hardt and Negri 2001; Haraway 2006) – instead the world and the people in it were flattened, reduced to a binary of use and commodity. Venkataramani expanded on this critique in 2012, sussing out just how insidious and stifling the logic of the user can be for “making positive change” when taken to extremes in project work.

the “user” frame limits the interactional phenomena visible to research whilst also limiting who are considered part of the phenomena…the second problem is that such framing assumes, and further naturalizes, market logic – the logic of exchange – as the dominant mode of relationship between the consumers of research output (“producers”) and the consumers of their products (“users”), thus eliding aspects of the relationship that have to do with civic commons and power hierarchies (4).

Indeed, despite anthropologists best efforts to reel in the language of UX to work for them, the more they seemed to work for it. Its lack of theoretical center left the brand open to becoming increasingly disarticulated by the diverse group of actors attempting to use the language to their own ends. Indeed, as Norman himself noted in a moment of somewhat ironic reflection,

I invented the term because I thought human interface and usability were too narrow. I wanted to cover all aspects of the person’s experience with the system including industrial design, graphics, the interface, the physical interaction, and the manual. Since then the term has spread widely, so much so that it is starting to lose it’s meaning…user experience, human centered design, usability; all those things, even affordances. They just sort of entered the vocabulary and no longer have any special meaning. People use them often without having any idea why, what the word means, its origin, history, or what it’s about (UX Design 2016).

Where words failed to capture the essence of UX, others tried to use diagrams and models as working analogies, though these too were plagued by similar issues of communicative generality and confusion. Moving from highly complex (see Figure 3), to oversimplified (see Figure 4), these models reflected the efforts of the highly diverse group of working professionals now tied to the term, struggling under the corporation to make it something more pragmatic, normalized, and standardized – something that could shift organizational practices directly, rather than remaining an ephemeral brand.

Figure 3. The UX wheel hieroglyphic.

Figure 4. The UX horse.

Indeed the issue with UX was very much the same as with the idea of the user itself. It was such a malleable term of reference that it stifled the ability of anthropologists to do what differentiated them from the start – bring cultural specificity and difference from outside the corporation within to enact change. Instead UX became a means by which the corporation could “distill” the outside world, purifying it, and making it ultimately look nothing like the outside, but instead, just like its internal self9. A reflection rather than a representation. Cohen again:

Because “users” refers both to actual people (the ones we interviewed) and to a kind of abstraction or methodological fiction (inspired by our users), they (and I mean both the notion and the actual people it abstracts) can be used diversely, pressed easily into service as research methods, marketing tools, advertising slogans. They are an exemplary human tool, in Suchman’s sense: highly reified (obscured) and themselves part of a larger process which reifies the theories, methods and projects with which they are associated (2005;7.)

In this laid the power of UX and its seduction as a means of corporate infiltration for ethnographers. UX was infinitely malleable within the organization. Without a theoretical core, what it offered was a ‘methodological fiction’ rather than scientifically produced research. It was a brand that did not represent people in the world, but instead morphed them into reified objects that reflected the corporations own image of itself. Indeed it was this nesting in corporate narcissism that gave UX its power. As Robinson noted, adopting UX for self-marketing purposes was a double edged sword,

The early [ethnographic] work changed the way in which large swathes of consumer, medical, and technology was developed. But in the post-.com world, the proliferation of ways to deliver up the hype around ethnography’s contribution to “new”, to deliver “innovation” at the paradigm-shaking level, has seemed a struggle…the way in which many professional practices market this work [such as UX] has come to have the perverse impact of limiting the range and nature of the types of inquiry that observational and ethnographic practices are understood to provide. “Discovering user needs” and the various forms of “product innovation” – each a class of claim—implicitly frame the work as “about” those ends in ways that elide much of the scope and diversity the work is capable of accomplishing (2010).

Indeed, many viewed the shift as just a first step in the commodification of the field by the forces of capital, an inevitable de-skilling of what was once artisanal ethnographic labor in a race to the bottom line (Lombardi 2009). The unintended drawback for some practitioners adopting UX as part of their now ‘open’ practice of ethnography, meant that their language began to reel them in – making their efforts to create change less effective, their methods less fundamentally transformative, and their core differentiator to representing “the other” in their native contexts, their anthropology as brand, lost (Suchman 2007). UX, the thing that was meant to reel in the corporation to “make the world a better place,” ultimately came to reel in the anthropologists.

UX’S COOPTION OF ETHNOGRAPHY

As ethnography masquerading as UX went from a purported “revolution” to a normalized mode of industrial parlance, researchers stories and the way they intersected the corporation began to change. This change was gradual, and often subtle, but it represented a slipperly slope – away from embracing complexity, towards a re-framing of culture as simple and dualistic. In a world of diversity, reducing our language of description to a binary (user and used), did not advance social science practitioners goals of making the corporation humanistic, but instead acted as a homogenizing force – remaking the world outside in the view of the corporation.

To illustrate this point, I offer a couple examples from interviews conducted during my time at Intel. When I joined the company in 2012 as a UX Researcher, it was in the middle of a large structural change. Two years previously the then CEO Paul Otellini had announced the next five year strategic mission plan to become a “user centered company,” providing the “best experiences” for their users. In response to a lingering post 2008 recession and lack of “innovation,” Otellini’s actions mirrored a broader movement in Silicon Valley among corporate elites at Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Apple, to create a “user centric” future, geared towards “solving” the “needs” of everyday people (Morozov 2014). Swept up in the solutionist-oriented change, anthropologists and ethnogrphers – the same who had experimented there for the decade prior – had to shift the tone and orientation of their work to fit the new frame of UX.

As one anthropologist turned UXer illustrated,

“We did a project looking at location data on notions of privacy and security around the world, from the EU, to India, to China. Our more quantitative arm ran a large survey to test if users would be uncomfortable with location based services monitoring their every move if the trade off was more convenience in their everyday lives. The surveys showed that tracking wasn’t a big deal – that most users didn’t care. Yet when we did ethnographic in-home visits, we found that every woman said it mattered – every single one. They didn’t care about the data being recorded, unless it meant corporations knew where they lived. They didn’t care if companies knew they were at a restaurant or an ATM, but if someone knew where they lived, this freaked them out.

None of the men we interviewed ever mentioned this. They figured, “if it helps me get through traffic faster, I don’t care, I’m not worried – if I can do better google searches, why not.” But it’s hard to compete with big numbers vs. ethnographic richness. In surveys they never asked the pivotal questions, they just asked general questions about ‘use’ and ‘experience’ in relation to the product in question – these don’t get at the very real issues. They don’t ask about home, or culturally embedded notions of privacy, or gender norms. In fact, we didn’t think to ask these things either until people volunteered the information to us when we sat down with them. Those surveys that prefaced “use” and “experience” over people missed the very real, cross-cultural differences in perception of tracking data based on gender, yet ended up having more weight with our stakeholders since it was in the language of UX” (Interview Archives 2016)

This instance may seem unique, but it is all too common in the way small changes in methods based on the frame of “UX” come to shape overall research findings, and subsequent product impacts. Without ethnographic language and richness beyond the frame of “user” and “used,” this work would have very likely led to new products that reinforced male gender norms through design, or other business strategies that entailed surveillance of the subjugated bodies of half the world – outcomes directly antithetical to practitioners foundational goal of “making the world a better place,” as well as putting businesses at risk to public outcry down the line.

Another ethnographer described her experience conducting UX research in India.

“We were looking at early adopters and local forms of technology innovation in India. We found ourselves interviewing college students struggling to make ends meet in Dharavi, the largest slum in the world. We asked them about their tablet and smartphone use, what features they preferred, how they had hacked their devices to run all kinds of apps they’d otherwise have to pay for. In the background, the richest man in India had built a billion dollar skyscraper home. The students told us about this in passing, as well as about their families lives making ends meet by making pots from a shallow pit of clay earth between their shanty homes, showed us their hang out spots where they liked to smoke, play a makeshift game of cricket, and hang out to watch illegally downloaded bollywood films on one of their Chinese made tablets, and their dreams of leaving Dharavi someday to become engineers or doctors.

We had enough to paint a rich picture of life there – of the role of class, caste, gender, tradition, industry, pollution, the pitfalls of globalization, neoliberalism, and so on. All the facets of this global place that make a person who they are. But of all of this holistic rich data we hoped to convey to our corporate stakeholders – to get them to champion the cause of these kids, to bring awareness to our role as implicit in this wealth inequality – our presentation was ultimately reduced to a discussion of one thing: How are they using these devices? What was their experience when on it? How often do they buy new ones?

We used images of the kids on their phablets, with quotes and short videos of them playing with their apps. We wanted to show more but it was all our stakeholders cared about. What we could not get across was that these devices were only one small part of a much larger picture – an essential picture within which to place use, as an escape from circumstance or a tool for realizing ambitions – though through our presentations, the devices became the privileged object of discussion by necessity. The people fell to the background, relegated to the role of users of things and how they felt when on them. To describe this entire culture and life way as an “experience” by privileging one piece of technology was a skewed representation – yet it was what was expected of us – it’s what was translatable to our stakeholders (Interview Archives 2014).

Indeed in this, almost tragic recounting of stories not told, we can see the very pitfalls of adopting a language of UX to describe what ethnographic data would have otherwise been able to more fully address. The sheer richness of data was systematically reduced to preference only one small facet of these peoples lives – their use of the object. Without concern for the broader socio-historical, political, and structural forces underpinning peoples lives in the slum, they became blanched, and flattened ‘non-people’ – standing in as figure heads to discuss only the devices in use, in only their moment of use. The user erased who these people were. It fetishized their histories, their lives, and instead re-wrote their stories in an a-contextual narrative centered around the experience of a product to be manufactured.

But the ethnographer’s hands were tied. Ethnography as part of product development was subject to cooptation. She could not overcome the expectation of stakeholders, or the frame of the research to be about the user and their experience. Indeed UX – the very tool of the ethnographer hoped would condition the corporation, had conditioned her and her work – corporatizing it, and eliding it of the very diversity necessary to drive innovation and positive social change.

THE PARADOX OF CONTROLLABLE INNOVATION

Why was UX so seductive? For anthropologists UX was a powerful self-marketing tool, but for business stakeholders, UX made a seductive yet structurally impossible promise – to ‘unlock’ the consumer mind in a controllable and predictable way, meeting the organizational demands of conformity while upholding ‘innovation,’ something that implies change. Not even in the history of the social sciences or philosophy could the vast difference and complexity of the human condition be so conveniently unraveled.

As UX grew across the valley, to many executives, engineers and other outsiders to the practice of research and design, it looked like a new standard for innovation had arrived. Indeed many of the arguments for the adoption of UX – to put the user first, to do iterative innovation that began with understanding “real people” out in the “real world” (Nafus 2006)– made a lot of sense within certain business logics. As Venkataramani discusses, the logic went something like this: “You make products for people. A better understanding of people will help you make better products… you need to understand them in their context—their homes and workplaces. You need to understand how they see and experience the world” (1).Users represented people after all, and people were the bread and butter of markets to be conquered. To know your users would inherently drive your business towards growth.

Innovation, as most Silicon Valley executives agreed, was essential for long term success in a fast paced and ever-changing, global marketplace. Yet the practice of how to “make innovation happen” was always something opaque, convoluted, and costly – something that needed discipline and repeatability like that of other industrial processes (Christensen 1997; Marx 2015). UX seemed to offer a middle ground to this dilemma, as one product development executive discussed:

We realized…to be a leader [in technology innovation] you must also have a reliable, repeatable discovery and development process; otherwise, products won’t emerge regularly from the pipeline. These larger processes are themselves divided into many smaller ones – in the case of product development, [for us] more than 3,000 in all. Today each of these processes is charted and on the way to being repeatable and controllable (Suchman 2011; 9)

Though corporations spent billions on research and design in their unending quest for “the new” (Cefikin 2010), their efforts to do innovation remained an uncomfortable expenditure, rather than an essential cost for long term growth. The nature of the corporation demands consistency and uniformity, indeed as one UX lead claimed, invoking a reading of The Innovators Dilemma, “corporations are highly optimized to produce what they’re highly optimized to produce…which tends to be one or two things…it’s hard to get them to do something different” (Interview Archives 2013).

Yet, innovation work is – like the world around us and the people in it – multifarious and non-conforming. It is precisely a recognition and upholding of difference that makes it opposed to corporate optimization of one thing (Hage 1999). Innovation happens at the seams, where boundary objects and ideas come into contact in new and unexpected ways (Starr 1989). Indeed, despite excessive spending on R&D at large companies, many “disruptive” innovations even today still seem to come from small and unexpected pockets of work, outside of corporate walls (Christensen 1997).

Though mythic origin stories of amateur hobbyists working in their garages to create ‘the next big thing’ transfixed work cultures and executives (Flynn 2010;44), it seemed the “essence” of what made these breakthroughs possible was, ironically, hard to capture by the very corporations these innovations eventually grew around them. As Suchman (2011) noted from her experience, in fact institutional structures meant to encourage and streamline innovation, often come to inhibit it, “I would argue, contrary the widely accepted narrative, that a site such as PARC is designed in important respects systematically to block innovation” (13). This tension – the necessary act of innovation for corporate growth vs. the institutional demand for uniformity and efficiency – is exactly where UX found its way onto the main stage.

UX promised to at last provide a standard of innovation work that both met corporate needs for uniformity in a clearly modeled innovation pipeline, but also captured the diversity of ethnographic innovation work. The field offered the focus, tools, and language to at last “unlock” the consumer mind by providing “winning experiences” in a consistent, methodologically proven, way – by placing the user at the center of the imaginary of iterative innovation work rather than the garage tinkerer whom the corporation could not replicate (See Figures 1 & 2.). Though as we have seen, what promised to be a new field through which to drive change, brought not a standard for doing innovation work, but instead little more than a popular brand for marketing it.

THE RISE OF UX AND THE FALL OF PEOPLE

During my time at Intel I had the fortune of having a long discussion with the head of UX research about the rise of the field as a new language of power in the valley. As a fledgling anthropologist, new to the field of praxis, naïve to the long history of ethnography in industry, I found the conversation particularly revealing. In it, we touched on the intimate struggles of getting research recognized and adopted, as well as the moral and ethical dilemmas of those anthropologists now grappling to control the language they had adopted in an effort to wed their research more closely with product development – and ultimately how they had lost out on the one thing they once felt they owned the representation of: people.

Shaheen: So why do you think…what is it about this moment in particular which has made UX such a hot topic? I mean, there are job postings all across Silicon Valley for UX X, Y, and Z…it’s become a major buzz word.

“I think part of what has made it [UX] compelling and seductive to imagine there is a set of disciplines that might unlock human desire is that we’re at a moment in time when the chief decision makers in most big companies no longer resemble the markets with whom they want success. The delta is growing, right, the delta between the key decision makers and the people they want to have their service, buy their stuff…you know in new start-ups those are often very close, right; ‘I made the thing I wanted for myself and then we see if it scales.’ What we’ve had instead is a series of companies who for demographic reasons, political reasons, political economy reasons – their key decision makers don’t necessarily resemble [them] demographically, psycho-demographically, aspirationally…

Shaheen: old white guys?

Well, even if they’re not, you know, I’m sorry; the guys who run Google aren’t all old white guys, but they also know they need to be successful in some other ways, with other kinds of people…the auto industry, some of the tech industry, certainly some of the others, [historically] haven’t actually had to think about the fact that people might be consuming their goods and services and experiences who aren’t like them…as the range and scope of markets shift, when your key decision makers no longer look like the markets you want to be successful in – you need interventions.

And, you know, social science and design thinking have been very neatly packaged as an intervention because they offer a bridge from the world of the boardroom to ‘the world everywhere else’. It’s an effective one; it’s got a disciplinary history; it has all of those things. I think at that level it makes sense to me. And it’s been conveniently packaged in lots of useful ways. I think, more interestingly for me, is there’s something else going on in that shift that is potentially both more intellectually and politically problematic.

Which is, we are now talking about users again. For me, the move between talking about people to talking about users is a really dangerous one. Because we… privilege the moment of use, right, whether it’s the swipe across the screen, the push of the button, the swipe of the credit card, the entry of data, the turning the key…it simply becomes what is happening in the moment of engagement/use. So there’s kind of a Marxist argument here that says, in fact, a focus on user experience is the ultimate expression of the alienation of people and stuff. Because we’re now just focusing not just on people, but ‘people in their moment of using things’.

Shaheen: I was having a discussion with a colleague earlier in a similar vein – you might say there’s even an ontological shift here. As corporations moved from talking about consumers to users, they also changed the frame of engagement, from being about “attracting repeat customers” or “consumers” who would otherwise use an object up, throw it away, and leave – to ones who are always engaged. The user implies a continued, ongoing relationship with capital and the corporations at the helm. It’s a new imaginary for the relationship of capital to the consumer, one in which there is no outside to capital – there is only the individual as they are defined by their continual use patterns. It’s a thought anyway.

It also means we’re privileging the notion of experience which I think is interesting. There’s something about that language – about affect10 being put back into science that I think is interesting. For me that notion that we’re all talking about user experience, not talking about people, is really interesting. There’s stuff that sort of falls out of the equation. I think it means there’s stuff we’ve had a harder time thinking through. If you don’t have to think about people as whole beings, with cultures, and histories, and practices, and habits, and idiosyncrasies, and you just have to think about, ‘does it need to be yellow or green?’ or, you now, ‘do they need to feel liberated in this moment using this product, and will it give them brand happiness?’ There’s some flattening out of humanity that goes on with that.

Shaheen: It certainly seems to be an ironic kind of departure from ethnography and the upholding of difference, as we are now sort of ambassadors to this user. At least that’s what they told me when I joined, “represent and evangelize the end-user voice,” whatever that means.

It doesn’t surprise me that UX has come up as the replacement language to globalization. As a linked discourse… Thomas Freedman complains about the world being flat, but really what he meant was America wasn’t exceptional any more. Globalization was never really a thing; we’ve always been global as much as we’ve been local. Goods and services have moved around the world for two thousand years, if not more.11 There’s sort of something about ‘what was globalization hiding?’, and I wonder – my question is always, ‘what is UX hiding?’, ‘what is being silenced in that conversation?’ I think there’s a number of things that get silenced. As soon as you say ‘user’, you don’t have to think quite as exquisitely and explicitly about gender, race, class, and religion. You also don’t have to think as explicitly about power, about, you know in a Foucauldian move12, the lines of its transmission kind of get erased. You go back to an ethno-methodological approach where it’s all just about the moment of use. Which for me was always the problem.

Shaheen: That’s a cool idea. The user as a replacement language for globalization. I like it. It keeps the system going, describes it, but now with a kind of “cleaned” palate. It gets rid of all the moral issues of intervening in the world – you’re just ‘filling needs.’ But then, does it offer the same kind of theoretical rigor of analysis as ethnography?

For me, I’m interested at a personal, professional and intellectual level about theory. When you talk about user experience you don’t have to talk about theory either. Design thinking, whilst deeply rooted in certain kinds of theories, it all just gets lost. It becomes a…’well we did ethnography’. Well, what does that mean? We talked to someone. Well that’s not an ethnography, that’s just an interview. Where do all the big theoretical moves that informed all of the disciplines that are now rolled up under UX go? Psychology is rooted in a set of important theoretical paradigms over the last hundred and fifty years; the same with anthropology, the same with sociology, the same with – in fact, all the things that cluster around industrial design, ergonomics, participatory design, human factors engineering, interaction design, HCI – all come out of very particular ideas about people and bodies and stuff. For me there’s something about the user experience that just erases bodies.

Shaheen: Bodies? Of users or of people?

Bodies, ultimately – it’s a bit feminist – bodies matter.13 So you want to put bodies back into the equation. We know that bodies as gendered and raced, classed, aged things do particular kinds of work and have particular kinds of desires that just can’t be tidied up into ‘an experience’. It’s always a singular user experience. I don’t think it’s easy. User experience is clean. We worry about user experience and I’m like… really? I like to worry about people.

[The corporation has] waxed and waned in terms of how much you need to pay attention to people. Who might those people be? I’m always curious about when a vocabulary pervades that way, and seems to have…become ubiquitous; you sort of have to ask what’s being disappeared. I do think it’s about users, in that [they’re] incredibly absent of bodies, and desires, and politics, and mess. And, of course, [people have] the ability to resist you. And non-compliance, which sort of disappears in that too. How do you talk about the people who don’t use the stuff? Are they non-users? Are they non-experiencers? …It’s kind of a compulsory acquisition. Then there is a question to ask, about; ‘is it political?’ Not in a kind of macro sense but in a micro sense, and to what end.

Shaheen: It certainly would seem that users are a kind of inherently a-political, non-people. But then why use this language?

I resisted… for a really long time… at every turn of the cog. My teams have always been called other things… I never wanted to do user experience…I don’t think it’s a helpful term. For all those reasons….but it wasn’t really a choice… [you] pick your battles. That wasn’t the battle. (Interview Archives 2012a).

CONCLUSIONS: WE MAKE THE USER AND THE USER MAKES US

In this paper I’ve attempted to show how the nascent field of ethnographic praxis went from something experimental and done on the peripheries, to something central to organizational form and the processes of corporate product development and innovation. As ethnography-as-method became separated from the field of anthropology, it was opened to new collaborations with adjacent fields (from design, to HCI, to psychology, media studies, and so on). This ‘opening up’ was largely done as part of the ongoing attempt by researchers to use their work to “make a positive change” in capitalism. Yet over the years, with many twists and turns and reinventions of the field, the practice of ethnography came to incorporate User Experience as a means of getting closer to product development. This language helped ethnographers to further normalize their work, and infiltrate the core of the corporation in the quest to change it and its productions. But in this recent adoption of the user, ethnographers found that the one thing that once made them distinct and differentiated (their representation of diversity of global cultures, the ability to think laterally with historical theoretical approaches, etc.) was lost. UX, though a useful marketing tool, came to change the researchers and their productions – taming the researcher who once sought to tame the corporation. This brought with it tremendous moral and ethical tensions for the group, as well as foundational questions of legitimacy still strongly felt in the field today.

Languages of power shift over time within corporations. User Experience has certainly made its mark as one of these, with reaching effects that will likely be felt for years to come. Indeed it is a language that has enabled many researchers to seemingly forge inroads, gaining influencer positions and opening doors, getting some of our ideas for change across to the corporation. This is an ongoing linguistic evolution for researchers translating their value; and there are many substantial cases highlighting success (O’loughlin 2014; Oygur 2009; Hassenzahl 2006).

Yet in the long run, with its normalization as an organizational language of choice and the conditioning of ethnographers away from exploratory roles, to product development roles, it has in many ways erased common theoretical critiques that other globalization discourses enable (from exploitation, to hegemony, colonialism, to race and gender, etc) and supplanted it with a new “clean” language for describing the messiness of people – deracinated from their contexts, and remade anew as users. The conversation about corporate aims has shifted. Their purpose is not about making profit, its about “building great experiences,” products are not about forced child labor to build components, they’re about “intuitive design.”

UX has allowed us room to side step the issues of capital that are inherent in the system. If the goal of social science researchers in industry is indeed “to make positive social change,” we can’t shy away from this kind of discussion. As one ethnographer put it, “We can’t keep churning out pieces of work talking about white millennial kids tapping on their phones, because they’re the next market” (Interview Archives 2012a). Are we really making an impact, or placating an inevitably exploitative system?

This is not simply a linguistic shift, it has performative effects as well. Mackenzie discusses the effect of models on markets with Wall Street traders. They create models they believe help them understand the shape of markets, but in fact those very models come to shape their own trading behavior and thusly the markets they engage with (2008). In the same way with users and experience, the lack of broader contextual understanding relinquished in privileging models of “users” over people causes the corporation to project its own internal interpretations of the outside world through the design of products. As people engage with these products, they too are shaped by the very structures, dialogues, and cultures of the corporation – becoming users first. No one is born a user, they are made a user. Indeed the logics of global capital are recapitulated in this dialectical way, with a new brand face.

What remains then, is the question of what is to be done?

The EPIC community has long been aware of these problematics, and has offered practical solutions for dealing with the issue. Many of these are wholly legitimate and I too would advocate them, such as designing for “publics” instead of users, forcing our work to think more broadly of our subjects beyond the confines of use (Cohen 2005; p20). Or using our work to encourage critical consciousness, produce more problems rather than solutionist insights, and devise tactical power strategies to reshape corporate hierarchies from within (Venkataramani and Avery 2012; 292). Or playing a more active role in “creating…new (external) bodies to consume our work” that might take to newly impactful domains (Bezaitis 2009 p160). These are all valid responses that many ethnographers have since employed in their day to day work. In due course a new language of power may come to replace UX alongside the next “tech breakthrough,” but perhaps an even simpler approach might be as effective.

UX is a brand, and in that it offers only general thematic direction. Perhaps then the way to deal with it is on its own brand-like terms. Taking a page from Madjburg’s 2014 EPIC presentation in which he announced the field should “divorce design” (2014); perhaps it is time we similarly “Divorce UX.” Ethnographers work, after our long and embedded history making change, is now essential to product development. Our practices are normalized. We’re on the inside and we have influence. Our work and priorities may have been tamed, or even coopted, but we still have the power to represent difference and foster innovation.

We are political. Our existence is political. Our work is political. UX fetishizes these politics. It is time to divorce the language of user experience, and inject politics back into our work, back into design, back into the everyday.

Shaheen Amirebrahimi is an Anthropology Ph.D. Candidate at the University of California Davis, completing his thesis titled, “A Moment of Crisis: Remaking Silicon Valley with User Experience.” He spent three years in the field working at Intel as a User Experience Researcher, during which he gained valuable experience and interview data for his dissertation.

NOTES

1This claim is in reference to a moment in 2012 when many of my colleagues and I were pulled into Silicon Valley during a wave of hiring and anointed ‘UX researchers.’ At this time large tech companies were publicly discussing their plans to become “user centered” as a means of re-igniting a slump in innovation (Economist 2013; Wise 2014). This was not new per-se – people centered innovation work had been happening for decades in tech in varying forms – but it was a kind of re-discovery that, coupled with new marketing programs, signaled an acceptance by corporate elites of the new language. The possibility for which came only after years of incremental work and negotiation done by veteran researchers – work which is ongoing and continues today.

2Though the aims of anthropologists in industry vary widely – from ‘opening discussions’ of techno-social/techno-material possibilities, to making more culturally sensitive corporate cultures – for the practitioners interviewed in this research, they claimed the rise of the language of UX, though necessary to communicate and translate the value of ethnographic insights to the corporation, ultimately stymied their full analytical potential. In a way “taming,” or making commonplace, what was once seen as “exotic” research. See Suchman 2007 for a discussion of anthro as exotic.

3An early example of which was Suchman’s hiring at Xerox PARC by John Seely Brown, and Robinson’s later hiring at the Doblin group.

4This phrase was a geo-demographic segment developed by Claritas Inc, later bought by Nielsen Company. It was a widely used consumer segmentation system for marketing in the US in the 90s.

5See Dourish 2004.

66 I’m thinking here of professionals like Bonnie Nardi, Eleanor Wynn, David Hakkin, Joe Dumit, Rick Robinson, and others.

7Though Apple has worked fiercely to maintain an occult mythos that they do no “user research,” and that instead their innovations come from pure brand genius, in fact the company has spent billions on UX R&D. This was revealed during the Samsung v. Apple case, ongoing since 2012, where the company was forced to release research studies showing the user value of rounded edges for their patent claim. See Roberts 2015.

8Though it is true that sister disciplines to anthropology – like HCI, human centered design, or industrial psychology – began framing research in terms of “users” as far back as the 80’s, many ethnographers held off from such framing as best they could before the rise of UX. Indeed as Robinson commented, “if one were to trace the origin of the word user, you’d likely end up in computer science, not product design or the social sciences – that is telling” of the ongoing tension felt by researchers (2016).

9For a deeper analysis of this “distilling” process I describe as part of the “research industrial complex,” see Amirebrahimi 2015.

10For expanded discussions on affective technologies see Gregg and Seigworth 2010.

11For more, see Friedman 2005, Appadurai 1996, or Harvey 2007.

12See Foucault 1977.

13For more, see Price 1999.

REFRENCES CITED

Amirebrahimi, Shaheen

2015 “Moments of Disjuncture: The Value of Corporate Ethnography in the Research Industrial Complex.” 2015 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings https://www.epicpeople.org/moments-of-disjuncture/

Anderson, Benedict

2006 Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso Books.

Anderson, Ken and Maria Bezaitis