As a social researcher rooted in the traditions of participatory innovation, I set out to take a design anthropological approach to study the early unfocused phases of organisational innovation processes, and explore ways of both challenging and supporting these. With an interest in understanding how the tangibility of design coupled with the analytical nature of anthropology can provoke richer insights concerning organisational practices, my research team and I designed an artefact, called ‘the tangible brief’, aiming to elicit real stories about the challenges practitioners experience in dealing with innovation. The artefact resembles the content of a design brief and aims to bring together practitioners around the task of creating briefs prior to evaluating the potential of new ideas.The paper sets out to address the challenge of ethnographic researchers navigating a complex landscape of organisational innovation practices, and attempts to reframe the roles we can take in the field. Along those lines, the research contributes to a nuanced perspective on how tangible artefacts can become part of organisational figurations, and thus explicate the challenges that the social and political structures in the organisation are causing. Findings show that design anthropological practices can provoke actionable insights revealing deeper layers of organisational structures and processes, thus expanding on existing theoretical perspectives mainly highlighting how these artefacts can serve as conversation tools to encourage consensus and collaboration.

Keywords: Design Anthropology; Participatory Innovation; Tangible Artefacts

INTRODUCTION

While ethnographic fieldwork produces empirical insights that describe what people do and how they understand what they do (Wolcott, 1995), it also enables us to understand cultural diversity (Marcus and Fischer, 1986). And although we as ethnographers attempt to depict accounts of societies, we also seek to provide cultural critique and explore the meaning of “the variety of modes of accommodation and resistance by individuals and groups to their shared social order” (Ibid: 133). Consequently, through a variety of methods, ethnographers have been and are continuously exploring ways of making the familiar unfamiliar to invite reflections on culture and practice. One emerging research field particularly engaged in this subject is design anthropology, which aims to reframe relations and challenge people to think differently about what they do and how they understand what they do (Gunn & Donovan, 2012).

In an attempt to understand organisational practices, ethnographic methods have been involved in a variety of studies (Yanow et al, 2012). As ethnographers, we engage ourselves in the field to depict practice-based and situated understandings of businesses, and inevitably come to entangle ourselves in the daily complexities of organisational life. Thus, it becomes central to acknowledge that knowledge gained in the field is not solely built from prosaic facts that are waiting to be revealed; rather, ethnographic insights emerge in the continuously built relations between people (Ingold, 2014). Ethnographers become contextually sensitive through their entanglement with the subjective realities of the stakeholders (Beech et al., 2009), and in some cases move past the social front that the stakeholders normally present to strangers (Moeran, 2007). Hence, through this active involvement in the field, during which our contextual understandings constantly develop, we come to depict the lived realities of everyday practices. This eventually enables us to facilitate conversations that make the familiar unfamiliar through explicating the relational, political and social dynamics of the organisation (Ybema et al., 2009). One way of inviting practitioners into these conversations is through tangible artefacts, particularly those designed with a situated understanding of the challenges an organisation is facing. By deploying artefacts that combine the tangible qualities of design with the analytical practice of anthropology, we allow ourselves a different kind of engagement. Rather than mainly describing the front-stage practices of organisations, we challenge and intervene into existing company structures, and attempt to elicit stories that go beyond those we are able to grasp through traditional ethnographic endeavours.

Within participatory innovation, where design anthropology makes up one of three pillars (participatory design and lead user research being the other two), findings highlight the advantages of designing and involving tangible artefacts that can instigate conversations to address businesses challenges. Previous research has shown how tangible tools encourage collaboration by building common ground for shared understandings, enable and unfold dialogues about business challenges, supporting company employees in exploring how these potentially could be addressed (Buur & Beuthel, 2013; Eftekhari and Larsen, 2012; Buur & Gudiksen, 2012; Buur et al., 2013; Buur & Mitchell, 2011). What yet needs to be studied is how these tools, through design anthropological exploration, can become part of organisational dynamics, potentially exemplifying or reinforcing social processes and political figurations.

The findings presented here attempt to expand on participatory innovation literature, by bringing forward a nuanced perspective on the influence of design anthropological tools. The paper challenges existing understandings and assumptions of how tangible artefacts involved in ethnographic endeavours can support dialogic interactions in company contexts. While the original theoretical premise is that tangible artefacts designed for specific organisational settings can support a diversity of stakeholder interactions, this research points towards an artefact enforcing two different agendas simultaneously. The artefact comes to act as a political tool, which on one hand supports prescribed management strategies, and on the other gives a voice to company employees. In the paper I seek to present how ‘the tangible brief’, which is a tangible artefact resembling the content of a design brief, went from supporting to challenging the agendas of the leadership team.

The Tangible Brief – The study presented in the paper is based on a research project aimed at supporting larger European organisations with new methods for working with innovation in early stages of their product development processes. The tangible brief is one of these methods. It was thought of as away to help an organisation deal with the early phases on innovation in a less unfocused and messy way. The tangible brief was particularly designed in response to the organisation’s request for employees to write design briefs, prior to being granted acceptance to work on any new innovations. While the employees were opposed to the thought of having to describe their ideas in such detail before maturing them to a level they would feel confident with, we as social researchers saw potential in developing a tangible artefact that would support practitioners in developing design briefs through collaborative exploration and negotiation.

Essentially, the design of the tangible brief was intended to translate some of the main concerns of a two-page design brief into physical objects. The two-page brief is particularly concerned with stakeholders, resources, strategic aims and project processes, asking the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ of project planning. We aimed for the tangible brief to explicitly involve practitioners in answering these questions, and to help provoke reflection and instigate fruitful discussions about their ideas and the directions in which these could develop. Using objects to express themselves, practitioners explore potential directions of their ideas prior to having to describe them in detail on a design brief template. As such, they are given the opportunity to explore their ideas before they are handed to the leadership team for evaluation. This moves the design brief from being an individual task to a collaborative one. It explicates the invisible creative process of employees, and at the same time helps them produce a brief that management would accept. To better understand the organisational practices, we as researchers saw the process of engaging the stakeholders in the design and testing of the tangible brief as a means to conduct ethnographic fieldwork. So, by engaging them in discussing these new work procedures, we found an opportunity to learn more about the practices, challenges and social figurations of the organisation. While designing the brief, we aimed for it to create a space that would enable us to ask more specific questions on how they deal with innovation, and better understand the roles and responsibilities of leaders and practitioners. Therefore, the tangible brief was intended to work on two different levels: as a support for design brief development and as an ethnographic undertaking.

Method – I take a qualitative research approach, eliciting real-life stories emerging in the organisation to understand the relational complexity influencing the ways in which front-end innovation work is formally described and practically organised within the organisation. As an entrance point, I conducted semi-structured 1:1 interviews looking into the formal structures of the organisation, to understand ways in which they deal with innovation. To add nuance to those insights, I observed internal project meetings and training workshops, while later actively taking part in activities, asking questions and challenging their taken-for-granted assumptions about their daily work. This initial fieldwork thus had the purpose of understanding the organisation on a general level, and slowly provoked responses about challenges that face practitioners and managers in dealing with innovation. As a natural extension of the formally planned fieldwork, the need to informally interact with and build confidential relations to the company stakeholders emerged, allowing me to tap into conflicts that on the surface lack potency, but in actuality have had quite a crucial impact on how their work practices finally take shape. I look to the concept of stumble data (Brinkmann, 2014), which acknowledges that unexpected events and conversations can be highly valued assets in attempts to understand people and their practices. I find potential to uncover new perspectives in informal settings, where people might have higher tendencies to share things they would not share in open discussions with their colleagues. As such, the formal and informal ways of collecting empirical materials provided me with an opportunity to generate richer insights and a more extensive understanding of the innovation challenges the organisation is faced with, and how they deal with them.

Designing Innovation Tools – As previously mentioned, the tangible brief was meant to support new work procedures; requiring the creation of design briefs prior to any front-end innovation activities. Department employees eventually discovered new opportunities in the tool, began questioning the validity of management’s decision, and in their responses showed that it could have different implications than the ones imagined at the point of origin.

As such, the tangible brief was designed to support management’s strategy for making front-end innovation more transparent in the organisation. Thus, management sought to ensure communication across departments and avoid undocumented projects with wasted resources that otherwise could be better spent in downstream development. The tangible brief would help the managers visualise the new work procedures. This would bring employees together across disciplines to collaboratively create design briefs that the leadership team would evaluate, and then decide on whether to invest in. During a couple of months the practitioners described more than 50 design briefs, yet the leadership team still had not made any decisions on which projects to invest in. Therefore, the practitioners started taking a more active role in negotiating the use of the tangible brief. They started putting their managers in the hot seat, to get them to make evaluations in the process of creating the brief. They challenged them to make front-end innovation a higher priority, rather than giving those resources away to downstream development. As such, we began the project by intervening in their practice and using the tool to provoke and elicit ethnographic stories. This is distinct from the more traditional ethnographic consulting approach, which begins in a distanced way by describing existing company practice, before moving to stages of recommendations and potential intervention.

The Organisational Context

The ethnographic study has been conducted within a large European product development organisation, focusing on a department developing technological components across product lines in the organisation. Thus, the department in question is a cross-organisational service division mainly driven by revenues earned through projects that need to be delivered to their internal customers managing different product lines. Hiring mainly engineers, the unit is divided into three sub-sections: electronics, mechanics and design. Each subsection is lead by a sub-section manager. Together with the head of the department, the three sub-section managers form a leadership team. At the time we initiated the ethnographic endeavours, the head of the department had only recently been hired. His main task lay in supporting the department in re-earning recognition among their internal customers. Due to a tough period of fire-fighting and missing project deadlines, he was aiming to re-organise the department. This meant breaking down silos and integrating innovation as a central component of their development process, to not only survive the coming years, but to keep up with competitors in decades from now.

The design manager (SCD) has been in the department for nearly 20 years, and has found his own way of working with front-end innovation in an unfocused and explorative way. The sub-section manager of mechanics (SCM) was hired to save his sub-section after a break down. It left them incapable of delivering projects on time, thus diminishing their reputation within the organisation. The third manager in the electronics subsection was quite passive in the whole process of changing development practices, and therefore does not play a role in this story. What became important to understand is how they work across the department sub-sections, and how the development process is structured. With the new head of department wanting to situate people in the offices around projects, rather than competencies, the employees and managers are expected to work across areas of expertise. Essentially, the product development process begins with concept and design development, before moving to manufacturing and testing. The concept and design phases are handled by the design sub-section, and run in iterations focused on developing ideas by testing concepts with end-users. These ideas are then handed to the mechanical and electronics engineers, who ensure that the product is technically feasible, before going to the manufacturing team. These two parts of the process are divided in such way, that employees from each sub-section are not directly involved in each other’s work. While this is the existing way of developing products, the department now seeks to integrate teams into a more unified process. Currently, designers hand over explorative ideas that the engineers often return by stating that they are not technically feasible. It usually leads to continuous negotiations and compromises that perhaps could have been avoided, if they worked together more closely from the beginning. This process has created much friction in the department, and could be well expressed in a comment by one of the engineers: “I have nothing against designers, but… There is a prejudice that designers are people that want appearance and smartness and are totally ignorant on natural and technological rules”. In one case, the merging of project groups led to an engineer with 25 years of experience in the department resigning, due to his unwillingness to work across specialties in a more integrated way. Within the department, this has created a stereotyping of both designers and engineers. For the managers, integration brings the challenge of facilitating the process of development, and ensuring that front-end innovation (concept and design phase) is prioritised in downstream development. In this concern, they see a need to allocate resources in a way that balances their wish to innovate and manufacture, with their need to continuously sell products. This is part of their strategy of staying responsive to rapid societal changes, and keeping up with competition; knowing that their development cycles can last for two-three years.

While the design sub-section only has six concept designers employed, the mechanical sub-section has up to four times as many mechanical engineers. This gives SCM more freedom in allocating people to do front-end innovation rather than downstream development. And while he is extremely interested in front-end innovation, there have been conflictual events between him and SCD, due to his eagerness to step across the boundaries of SCD’s area of responsibility. So, although new work procedures in the department initially seemed to be reasoned by budget cuts, ethnographic investigation revealed that these changes were due to complex social relations and managerial challenges.

Three Managerial Perspectives – To briefly lay the groundwork for why new work procedures were introduced, we need to balance three managerial perspectives concerning front-end innovation activities across the department. As a point of origin, specific conflictual events have challenged the social dynamics in the leadership team, and led to frictions emerging in the relation between the SCD and SCM. While the design manager (SCD) has been running his sub-section as a separate unit, feeding the rest of the department with innovative ideas and enabling them to stay responsive to market changes, his sub-section was perceived as a silo. The sub-section manager of mechanics (SCM) has not been in the department for much longer than the head of department, but has been particularly successful in building the competencies of his sub-section. While his responsibility is limited to his own sub-section, he is also quite interested in front-end innovation, due to the lack of technical restrictions. According to the head of the department SCM has on several occasions attempted to involve himself in front-end innovation work, and has been warned against this, so as not undermine the responsibility of SCD.

According to SCM, he has been excluded in the development of front-end innovation, and has on several occasions been surprised by SCD introducing entirely new ideas, eventually affecting SCM’s department due to an incorrect estimate of resources required to develop them. So, while SCM expected minor changes in some product lines, and had allocated resources for just those, he has subsequently been caught off guard after SCD introduced and handed over his subsection’s new ideas. SCD did this to protect his department from being robbed of the chance to develop far-reaching innovative ideas, and to avoid having to stick to launch projects. Due to these events, SCM started rejecting the idea of having to constantly accommodate the needs of SCD’s sub-section; particularly during time periods where he allocated his manpower for other projects that he had pre-planned. With an already articulated interest in involving himself in front-end innovation activities, he raised his concerns to the leadership team. He argued that they needed increased transparency across the subsections, to ensure that resources were well spent, and to not waste work hours on ideas that were hidden in the drawers. Additionally, he wanted to ensure that ideas were not suddenly introduced, leaving the department unable to accommodate the amount of work necessary for the proposals to be ultimately realised. His solution to this issue was thereby to introduce new front-end innovation procedures, that would require everyone to develop a detailed two-page design brief explaining the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ of their idea. Handing this to the leadership team would enable them to make decisions on which ideas to invest in, thus keeping track of all activities running in the department. The SCD, in his position, could not oppose this request due to the risk of appearing to waste resources and concealing projects in the drawers. He did not see the value in it either; as it would restrict the creative workflow he had allowed his employees to work in, up until now. He would no longer be able to allow his employees to mature loosely defined ideas over longer periods of time, and would instead have to constantly allocate his resources to launch projects. In line with SCM’s arguments, the head of department imagined that this new work procedure would enforce his plan of ensuring that his department can work across disciplines, and thus help them create a project culture, rather than a silo driven one. As a whole, the leadership team decided to introduce new work procedures (in the form of design briefs), ensuring that none of the sub-sections would be working on new ideas without their approval. In the bigger picture, they perceived this as an approach to increase transparency across the department, as well as preventing a waste of resources. This story basically looks different from each of the three managers’ perspectives, but has in practical terms led to the introduction of new work procedures that they are still trying to adapt to, and find ways of easily implementing.

Introducing New Work Procedures – As mentioned, one of the attempts to increase transparency to ensure alignment in the department, while allocating resources according to what was needed, was to introduce the design brief. Department employees, particularly the designers, were previously spending time developing ideas that were not yet matured. While these were typically hidden in the drawers for a long time prior to being defined as projects, this was about to stop. Beginning August 2016, employees were not allowed to work on any ideas unless they had presented the leadership team with a two-page design brief describing their idea, the resources needed, the stakeholders involved, etc. If the leaders then agreed that investing in that particular idea would bring value to the organisation, the employees would be allowed to work on it.

Many of the employees rejected this idea with the argument that their creative process would be lost, and this new procedure would not allow them to explore their ideas before putting them into structured explanations. However, the new work procedure was still presented as a necessity for the department to stand strong and survive the budget cuts by corporate management. While SCM seemed content and secure about the decision when it was presented at a meeting involving their middle managers, the design manager seemed to be more hesitant. He seemed aware of the consequences for his department, which had been surviving on maturing loosely defined ideas in the drawers, rather than immediately introducing them to a department that was not yet ready to deal with them on a more technical level.

As part of the process, the department hired an external design consultant, who we as researchers consulting the organisation had no relation to. The consultant would help them develop a new process for front-end innovation, with a specific focus on training the department practitioners in writing design briefs. For the practitioners, this was quite challenging due to the level of detail the design brief required. In response to this challenge, we found an opportunity to develop a tangible artefact that would acknowledge their creative process, and ensure that there was room for explorative and meaningful discussions prior to writing a design brief.

THE TANGIBLE BRIEF

Essentially, the tangible brief consists of four activity components, each addressing a central issue in how teams work on an idea, and each of which employees have had struggles defining when filling out the design briefs. The four levels are presented below:

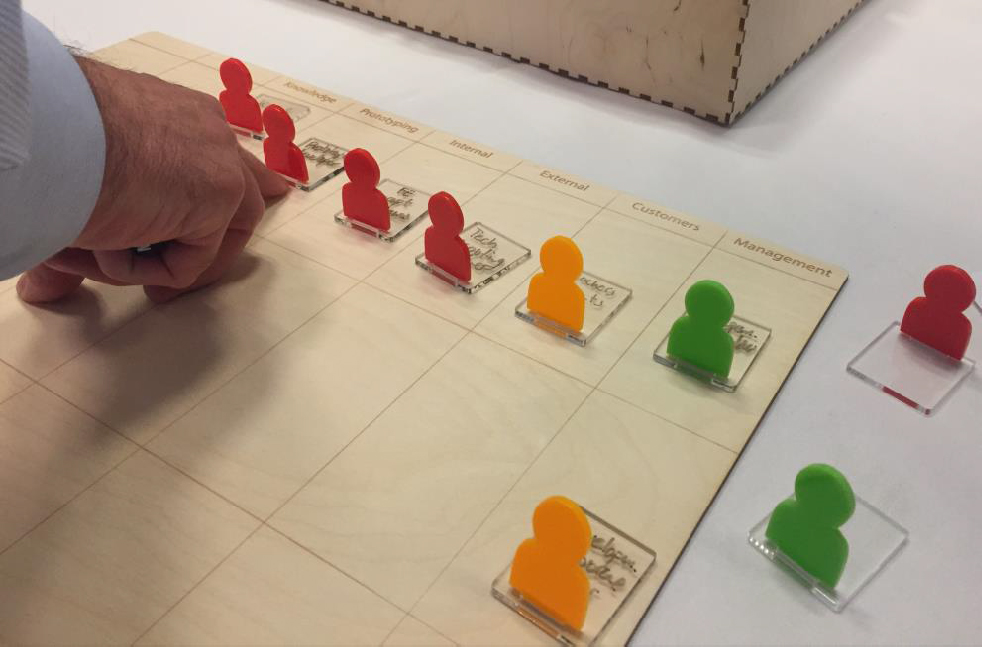

- Stakeholder Involvement: This activity asks participants to consider which key stakeholders they potentially have to engage with in the project, directly or indirectly and internally or externally. Participants place small acrylic figurines on the board, which is divided into different stakeholder categories (i.e. external, internal, knowledge, prototyping, management) and according to time, depending on when in the project process they would need these to be involved. They are additionally required to decide the impact of the stakeholder on their project, and thus choose which colour the stakeholder needs to be given. Green means ‘nice to have’, orange means ‘necessary’ and red means ‘crucial’. One example would thereby be to categorise one stakeholder as an external supplier, who is crucial (and thereby red) during the last three months of the project. Once they have agreed on this, they place the figurine on the board. In this way they negotiate the involvement of stakeholders, and create for themselves an overview of the people they need to engage with for the project to be successful.

Figure 1. Participants allocate stakeholders on the board, according to importance and times at which they want them involved.

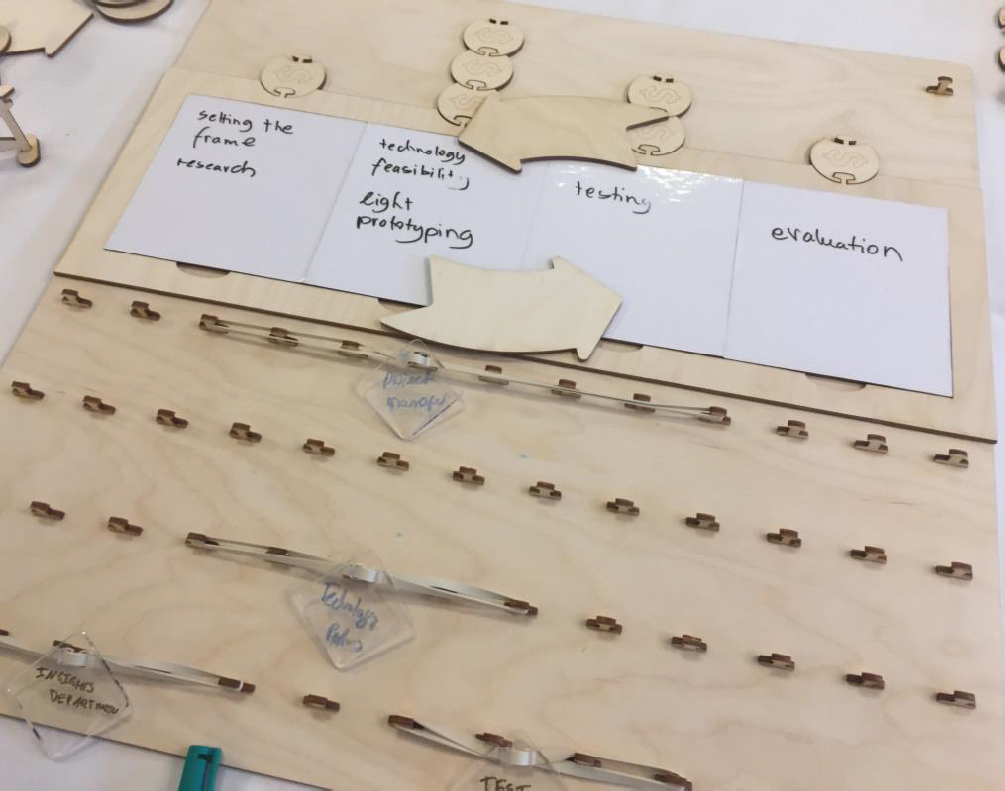

- Resource Allocation: Here, participants are invited to consider the resources needed for their idea to become possible. They are given a second board with four wooden squares in the centre, which they need to divide into time periods (i.e. three months per square for a one-year project). On these, they have the option of placing small flags (representing milestones) to consider where there might be important meetings, deliveries or the like. Coins are provided as a budgetary representation of the project costs. The coins are placed at one end of the board, providing an indication of the amount of money required within each time frame for the project to become possible. The money could for instance be spent on materials or external knowledge alliances. At the other end of the board they need to allocate internal resources in the form of manpower for the project. They are given acrylic pieces attached to rubber bands. The name of the employee is written on the pieces as well as the percentage of time he/she needs to be allocated to the project. Then they stretch the rubber band as far as it is necessary for that employee to be involved. It could be for just one week of research, or for 10 weeks of prototyping and testing.

Figure 2. Participants negotiate the amount of resources needed to cover project costs.

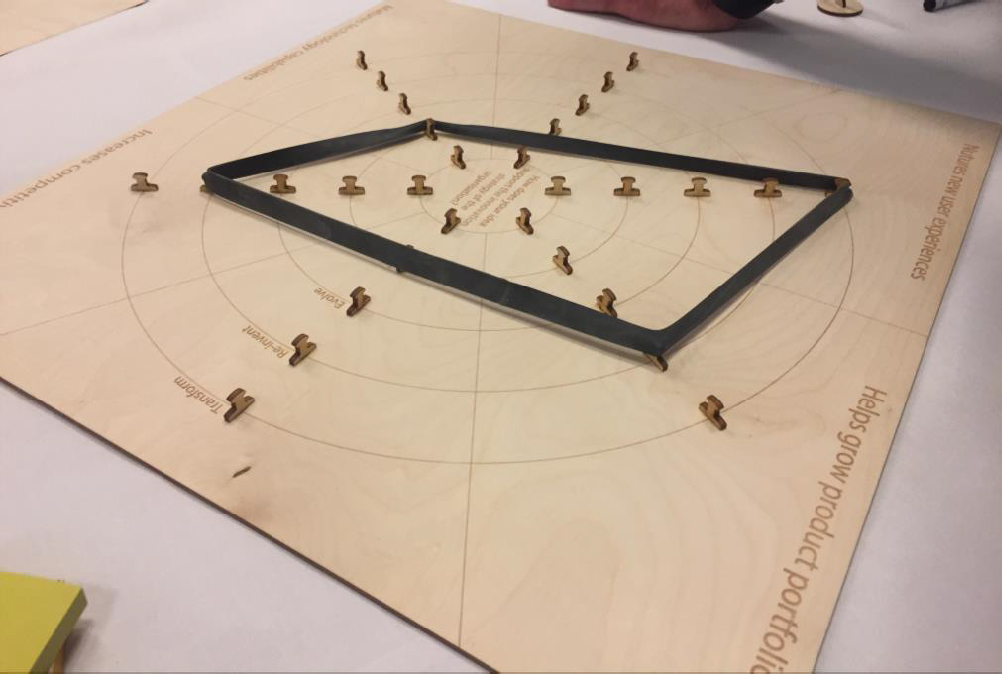

- Strategic Positioning: The organisational strategy emphasises different goals within front-end innovation work, and some of these are engraved into a spider web on the third board. In the centre of the board the following question is posed: How does your idea support the strategic goals of front-end innovation? The group’s idea is thereby to be evaluated in accordance with how well it supports the aims. There are five different ways their idea could support the strategic goals: not at all, improves, evolves, re-invents or transforms. Two of the areas are empty and allow participants to formulate a vision themselves. Once the web is fully completed they will have an overview of how their idea supports existing strategic initiatives within the organisation, and could also get them reflecting on where they could raise the ambitions of it.

Figure 3. Participants position their idea according to the strategic aims of the organization.

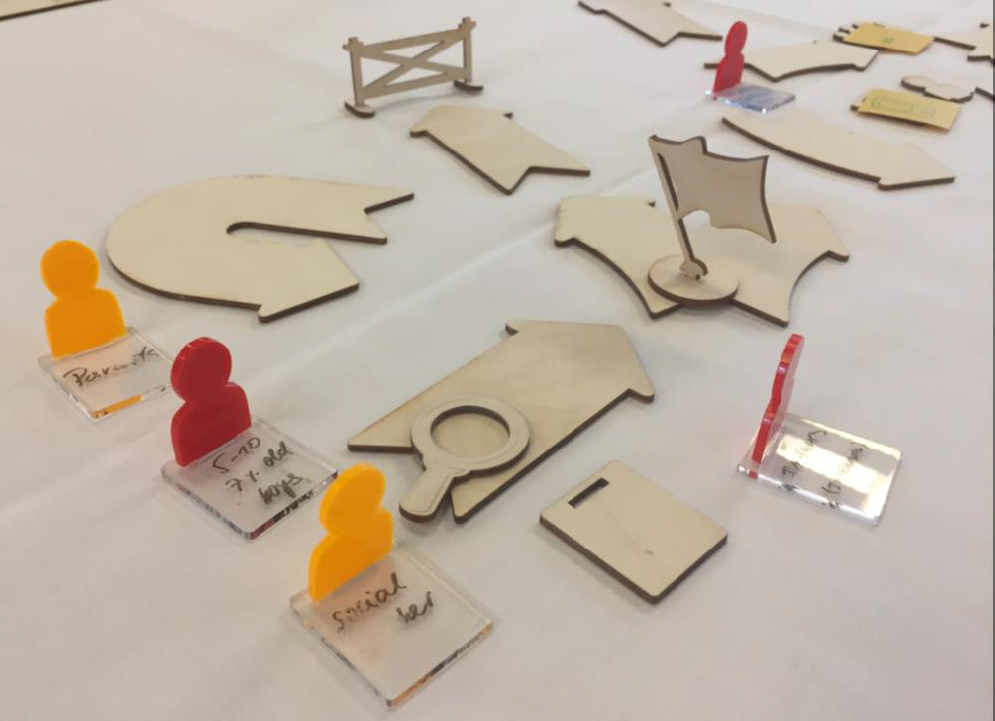

- Process Overview: In the bottom layer of the box lays a set of arrows cut into different shapes (i.e. linear, curved, u-turns). They are additionally provided with a set of different elements with particular meanings (boundaries, money, people, decisions, milestones etc.). Participants are asked to build the process they might have to go through for the idea to be realised. They are asked to place the objects according to where they think they will meet challenges, where they might have deliveries, decisions, tests, etc. Visualising the process will encourage participants to discuss whether their previous estimates essentially make sense, and potentially discover challenges that could prevent them from being able to complete the project or initiate the development of the idea.

Figure 4. Participants create an overview of the process they estimate themselves going through in developing the project.

The combination of the four levels was intended to create a collaborative space for participants to discuss, challenge and reflect on the ideas they aim to nurture. Essentially, this allows them to imagine the potential of an idea prior to being required to rigidly describe it on a two-pager for submission to the leadership team. In this way, the tangible brief was meant to give them the freedom they found themselves deprived of when the new work procedures in front-end innovation were introduced.

The Tangible Brief in Action

The design of the tangible brief emerged as a collaborative process between us as a research team, and the practitioners as well as managers in the organisational department. Having reached a point where the tool had developed, and was ready to be tested by a group of practitioners from both sub-sections, our research group organised a pilot workshop with two smaller teams. Each of them involved one of the sub-section managers. The pilot workshop was organised around two different sessions. The first session was for testing the tangible brief, to explore what kinds of conversations it would instigate. The second session was to reflect on the experience of using the tool, and to discuss how they possibly could involve it in their attempt to create design briefs. Data was collected in the form of video and audio recordings as well as field notes. In the following sections, I will dive deeper into the empirical materials and the role of the tangible brief in revealing and challenging social figurations of the organisation.

The Tangible Brief as Enforcement of Management Strategies

As a point of origin, the tangible brief was designed to support management strategies, enforcing newly described work procedures that would increase transparency across sub-sections in the department. The tangible brief was thus sought to help managers easily implement their idea of focusing and structuring front-end innovation into design briefs, and avoid having practitioners working on ideas that are hidden in their drawers for longer periods of time. Rather than management having to find ways of explaining their concept of developing a design brief, the tangible tool put their idea into practice, allowing for new conversations and questions to emerge as a natural development of the workshop. From a research perspective, its design is also intended to generate a richer understanding of their innovation practices, by drawing on the emerging conversations. At the workshop, the tool invited participants into discussions that would advance them into asking questions about procedures and structures. This enabled their managers to articulate how they would be working with front-end innovation going forward. Part of the discussion went into explaining the slightly detailed differences between a brief, a work stream and a project; differences that should have been clear to practitioners working in the department. Although one of the managers seemed somewhat concerned that his employee did not know how to distinguish between different procedures, the workshop provided a space for those questions to be posed and for everyone to become clearer on the organisational structures.

As such, our initial aim of organising the workshop was to test the tangible brief within the department, and better understand how it could support the new work procedures. This would enable us to offer them a tool that could directly support their processes, rather than acting as an add-on and thereby eventually become neglected due to it not being a direct fit. After the test workshop, the design changed slightly. The two managers asked us to make it more specific for it to reflect the content of their two-page design brief. On several occasions, SCM explained that the organisation runs as a big well-oiled machine already, and that it does not easily accept any new methods that could influence efficiency. He articulates: “If you want to introduce something new it should have a specific value for the organisation and fit into an already existing step in our processes, rather than adding another one. There is no need to overload employees with additional processes or tools, so I would encourage you to design something that would help us with an already existing challenge …. which right now is the briefing process”. And that is what the tangible brief set out to do – support a newly changed process, by introducing a tool that would ease the process of working with front-end innovation under new circumstances, requiring a higher level of detail from practitioners wishing to explore new ideas.

As part of a meeting following the pilot test workshop, both managers and practitioners were invited to influence the further development of the tangible brief. In response to some comments on the tool being very explorative and open for discussions, SCM articulated the need for it to become more aligned with their already existing process and asked one of his employees to send me the documents, from which I could extract the terms and symbols they already used. As designers of the tangible brief, we attempted to argue that the tool was not meant as a planning tool of projects, but rather a conversation starter that would get them to discuss and reflect on their ideas. We saw it as a way of challenging them to not immediately assume that an idea is worth investing in or not, but to invite conversations that might lead to the emergence of new meaning. However, the leadership team insisted that it would have to be closely aligned with what they already do, in order for it to support their processes, and for the employees to learn how to collaboratively develop the design briefs. It seemed that their perception of our role as researchers shifted during the project. To begin with, we were the designers of a new front-end innovation tool, but as the collaboration evolved we were trying to disrupt their new work procedures and challenge them to think differently about the purpose of the tool. However, the managers held on to the idea of the tangible brief being a representation of their design brief, and we went on with designing it for that purpose.

The Tangible Brief as Practitioners’ Advocate

In opposition to the managers’ request for a tool that would align to their formally described work procedures, their employees found ways to use the tool to acknowledge and support their creative processes. In allowing their ideas to mature at a conceptual level, rather than plan the development of an idea that was not yet existent, they were challenging each other and their managers to think differently about the process. Rather than simply accepting the new work procedures, the practitioners on several occasions opposed the idea of having to present management with concepts they had not yet had the chance to explore on their own. As I was interviewing one of the designers about the new procedure and his understanding of the usefulness of the tangible brief, he said to me: “But I mean, this tangible brief is not necessary before the idea becomes further developed. I could easily just go to my manager and say I want to spend a few weeks exploring and he will allow me”. As I informed him that this was not the case anymore, he looked at me as if I was the one who had misunderstood something and added: “No it cannot be like that. That is seriously nonsense. Why would I have to do a brief on something I do not even know the potential of yet? It would not hurt anyone if I spent a few weeks working on it besides my daily work”. As I informed him that those were the new procedures he stood there looking at me utterly confused and finally said: “That is really nonsense. Now that is bureaucracy”. We then went into discussing how the tangible brief potentially could help him and others to explore the potential of the idea, rather than use it as a tool for planning an upcoming project in detail. At another interview, one of the employees admittedly said that he cleared his schedule completely when he found that we would have a meeting/workshop concerning the tangible brief. He agreed that the tangible brief could be used as a tool to support them in developing briefs, but emphasised that more importantly the setting of our collaboration, and how the tool was integrated in our conversation was what he valued. He explained it as being his only outlet to discuss front-end innovation with the leadership team; a space where he could address his concern of not being allowed to mature ideas on his own, prior to it being an official work stream. He stated: “Us working on this with you creates a safe environment for us to prioritise front-end innovation, and to talk about the things we on a daily basis are just informed about and asked to do, without discussing the implications of any of it”.

Similarly, in conversations with other practitioners engaged in working with the tangible brief, we came to realise the seriousness of having to describe ideas that had not matured yet. This prompted different types of conversations at the meetings between them and the leadership team. In a meeting following the pilot workshop, we discussed another design iteration of the tangible brief. The conversation happened to especially revolve around the third board, which addresses the strategic goals. While SCD and SCM argued that the strategic aims had to be broad and address the strategy of the entire organisation for their department to act as a value-adding business partner, their employees did not agree. At the meeting, the leadership team was particularly challenged by one of the younger designers, who did not seem to accept the broadness of their strategic goals, nor that he should be forcing his ideas into them. He argues that: “The strategies you defined became insufficient in the projects and in the ideas we develop. They need to be operational, and at the moment they are not”. His manager replies: “Well, these should help you realise if your ideas are sufficient or not. It is just for us and corporate management to see, where we as an organisation are heading; those are the parameters we will be evaluated from, by the end of this year. Probably many would find your ideas relevant, but that is not what you deliver to. We need to be a value-adding business partner”. It is obvious to see that the designer is getting frustrated, and gets back to his leader saying: “Maybe that is why all our projects end up being the same. Because we never know how to address the strategic goals of front-end innovation, and we always need to be a value-adding business partner. We end up just solving the projects our customers give us, because they pay the money… I really do not understand why we are not prioritising the exploration of new concepts, that could help us stand as front leaders in 15 years from now”. The tangible brief appears as a tool supporting his arguments. He points towards the board and stretches the rubber band to explain how he did not find it valuable to simply pretend that his idea would be supporting a strategic goal, which he found to be too abstract for him to know how to address in practice. The fact that the tangible brief was placed on the table in front of them as an object clearly stating what their new work procedures would be, allowed for direct confrontation and negotiations of not only the briefing process, but also their prioritization of front-end innovation in the department.

The Tangible Brief Enforcing Two Different Agendas

Through working with the tangible brief across different levels and allowing it to be tested in an environment where both managers and practitioners were present, we continuously came to understand how it was working different agendas. As a starting point, it aimed to support the recently enforced managerial agendas as a way of simplifying the introduction of new work procedures, framing our work as the right-hand of management. Secondly, it operated as a provocation (Buur and Sitorus, 2007) allowing us to dive deeper into the organisational design and innovation challenges. What we had not expected was the opposition of practitioners against using the tool as intended by the leadership team. Thus, the tangible brief quickly became a tool of which the purpose and meaning were up for negotiation, rather than set from the beginning. The tool became a way of challenging and balancing perspectives across different hierarchical levels in the organisational, rather than means for creating consensus and fostering collaboration.

While the leadership team from the beginning insisted that the tangible brief would need to support their specific practices and help implement new work procedures, things eventually took a turn. In the beginning we were opposed to their idea of the tool, in a detailed manner, resembling the planning of a work stream, yet that was what the leadership articulated a need for. When we later organised a workshop involving the leadership team, the practitioners and several other academics and industrial practitioners, SCM’s response was different. By the end of the workshop we invited an open discussion to evaluate the potential of the tangible brief to be implemented in practice. SCM stepped forward stating that he now found it too restricting. He did not find it explorative or playful enough for front-end innovation activities. He argues: “We wanted this tool to give the people freedom, but I see that this freedom is being taken away as soon as you put people into the process [of developing the brief]. We need to build something into the tool to go back to this freedom. This tool should give the opportunity to find innovative ways of getting to a solution. There are a lot of stage gates in this, and probably we would like to have less”. He then states that being involved in the process of developing the tangible brief has been a very rich learning process. SCM’s reflections show that there has been a shift in his understanding of what the briefing process entails, and what challenges it could bring to their department. While some of the participants expanded the tangible brief by bringing in small toys and other objects to allow for a more diverse conversation, SCM finally also stated: “I think the tool has been hacked today, and that is very good”.

In retrospect, the process of developing and testing the tangible brief has caused an intense involvement of both practitioners and leaders in the department; and more importantly, it has allowed for new conversations and meaning to emerge. While the initial objective was to support management’s agenda, and design an artefact that would allow for collaboration and consensus, the tangible brief prompted a process we had not predicted. What finally gave us the most evident confirmation that the tool had provoked political conversations and challenged the social structures of the organisation was a meeting we invited the department to.

As we met both the leadership team and the practitioners, they informed us that they no longer needed the tool, and that they would not be creating design briefs for the rest of the year. Surprised by what we were presented with, we came to understand that the tangible brief had served as a provocation in the organisation; in one way or the other, supporting the practitioners in voicing their concerns and thereby allowing for new dialogues to arise. Thus, rather than immediately accepting that the tangible brief would help them develop design briefs, they involved it as a way of negotiating the new work procedures. According to the practitioners, this eventually lead their managers to the realisation that nothing actually came out of the design briefs they had developed, and that they were trying to uphold an image of prioritizing front-end innovation, when in fact they were not able to at the moment.

The decision described above, inevitably had an impact on two different levels. On one level, it challenged the relation between practitioners and leaders in the department, allowing for new conversations to take place and affording the employees a bigger say concerning the future of front-end innovation work. On another level, it reinforced the frictions between SCM and SCD. This is due to SCM proposing increased transparency between the sub-sections, and thereby introducing the idea of the design brief, yet later realising that it would be too restricting. Another part of the reason why the idea of a design brief was discarded, is due to the fact that at the moment, SCD’s employees do not have time to work on anything but launch projects although they are the ones officially hired to do front-end innovation. It thus became clear that only SCM’s employees would have time to work on front-end innovation, even though they are not hired to do that. As such, this would prove SMC’s wish to step over the boundaries of SCD’s area of responsibility. Thus, creating another challenge for SCM with the department manager, who previously had warned SCM against involving himself too much in front-end innovation and hence disregarding the responsibility of SCD.

INQUIRY BY MEANS OF INTERVENTION

Carrying out fieldwork in a continuous way over a period of 14 months and building confidential relations with the stakeholders within the organisation enabled us to explore different means of provoking new insights and intervening into their practices. As part of increasing transparency across sub-sections in the organisation and developing design briefs in front-end innovation, we designed a tangible artefact, which we call the tangible brief. The tangible brief was originally intended to help designers and engineers collaboratively work on developing design briefs to find focus at early stages of their idea development. However, it eventually took the role of an artefact that would provoke fruitful discussions around their practices, and challenge their managers into reconsidering ways, in which they have planned and intended to organize front-end innovation activities. As such, the tangible brief inadvertently ended up deconstructing the purpose of the design brief. As new conversations emerged the tangible brief soon led to the elimination of the design brief procedure altogether. If this had not happened, there is a high chance that the organisation would still be struggling with the design briefs today.

In the participants’ interactions with each other and the tool, we came to understand how it stirred conversations that led us to better understand their underlying concerns about their work practices, and the social structures built around these. The workshops and meetings emerged as dedicated spaces for them to discuss particular ideas, and use the tangible objects as a way of explaining themselves, challenging each other and imagining alternate futures. The tangible brief thereby quickly became another access point for us to generate ethnographic insight, and we consciously took that into consideration as the design process unfolded. Thus, combining the tangible nature of design with the analytical and comparative study of anthropology, we came to provoke insights and stories that we had not been aware of. Nor would we have been able to elicit these through the conversations we continuously found ourselves part of, formally and informally. In engaging with the tool and discussing the development of design briefs, the participants disclosed concerns about their inability to understand front-end innovation processes and work procedures that their managers had recently introduced. Therefore it opened up new conversations about their practices and a request for negotiating department priorities, strategic aims etc.

In the paper and through designing the tangible brief I focus on the quality of conversations (Buur and Larsen, 2010) emerging as a result of gestures and responses in the interactions between practitioners and managers, and explore how the tangible nature of the tool nurtures interactions that trigger participants to stress concerns they had not had the opportunity to articulate in any proper forum, prior to being presented to them in such an explicit way. In my attempts to conduct fieldwork to better understand the underlying challenges they experience in dealing with front-end innovation, I found myself entangled in political and social structures I had not anticipated. Initially, the tool seemed to support management in implementing new strategies and work procedures in a pain-free way. However, it started generating new insights about the organisation, and uncovering themes that I had not been aware of nor directed into asking about during previous ethnographic endeavours. I argue that inviting tangible artefacts into ethnographic practice emerges as a valuable way to create impact on the type of access we as ethnographers are allowed in the field. I find that ethnographers can move beyond the “classic” modes of ethnographic consulting in business—in which we offer recommendations for change through mostly verbal forms of communication—and instead instigate change while simultaneously generating new knowledge about organisational life.

Tangible Artefacts in Ethnographic Fieldwork – Participatory innovation tools have previously shown a unique capacity to “contribute to a high quality conversation” (Eftekhari and Larsen, 2012:299). This study has shown that tangible artefacts involved in ethnographic endeavours can play different agendas, rather than simply supporting collaboration. So what may we learn from this experience? What does it teach us about ethnography and participatory innovation? Was the discovery of the tangible brief as a political tool simply a matter of chance or can we say more about it than that?

I argue that this experience is not a simple result of accidental findings, but has the potential to shift our field to consider its role as intervening in the organisations we work with. My argument here is that within organisational participatory innovation settings, tangible artefacts may open new lines of inquiry. By approaching design and anthropology and their interrelation as ways of generating insights, tangible artefacts have the potential to supplement and complement ethnographic field methods. As such, the design of the tangible brief and the ethnographic endeavours were in constant dialogue. This allowed for new discoveries to emerge through a situated anthropological study particularly inspired by the design process. As Otto and Smith (2013) state, design anthropology becomes a way of both analysing and doing in the process of generating insights. It also becomes a way of reflecting upon situated relations between people and to go beyond explanation to challenge and reframe usual dialogues (Smith and Kjærsgaard, 2015). Through interventions and material engagements in situated contexts, one creates opportunities for change (ibid). Thus, provoking the researcher to question initial assumptions, re-frame practices and social relations. Here, it challenged me to treat ethnographic fieldwork as an integrated part of the participatory innovation process. As such, I was not seeking a final destination of gaining ultimate knowledge about the field, but rather engage with the field to test, challenge and develop my understandings of their innovation practices.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The paper explores the role of a tool we call ‘the tangible brief’, and shows how it was initially intended to increase transparency across department sub-sections by creating a space for front-end innovation to be discussed. However, it eventually ended up serving as a tool highlighting the politics at play inside the organization. I underline how this work opens up new lines of inquiry towards exploring the shifting roles of tangible artefacts in supporting ethnographers to conduct fieldwork. I prompt us, as ethnographers in the business world, to reimagine our practices, and our roles and relationships with organizational stakeholders. Instead of maintaining the “consultant” as a role model, we could consider our role as designers, disruptors or something entirely different. This leads to my point of ethnographers being able to contribute with not only the field knowledge we generate, but with the things we can do in organizations. It goes in line with Powell’s work on social mediation (Powell, 2016), where he argues that we might find ways of challenging perspectives within organizations. He argues that rather than neglecting the importance of outcomes like those of reframing relationships, we may reconsider the scope of ethnographic practice, and move beyond the textual product and the ability to provide organizations with recommendations for change. Doing that, we could perhaps engage more richly with the back-stage challenges and social structures of the organization to challenge taken-for-granted assumptions, and contribute with increasingly nuanced perspectives on organizational innovation practices.

Wafa Said Mosleh holds a MSc in IT Product Design and is currently pursuing her PhD in Participatory Innovation at SDU Design, Department of Entrepreneurship and Relationship Management, University of Southern Denmark. She conducts research in larger product development organizations to understand the emergence of front-end innovation practices. wafa@sam.sdu.dk

NOTES

Acknowledgements – I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my colleagues at SDU Design for their valuable help and suggestions during the development of this research. Thank you also to Michael Powell for the constructive feedback in shaping this paper.

REFERENCES CITED

Beech, Nic, Hibbert, Paul, MacIntosh, Robert and McInnes, Peter

2009 ‘But I thought we were friend?’ Life cycles and research relationships. In Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexities of Everyday Life, edited by: Ybema, S., Yanow, D., Wels, H. and Kamsteeg, F.

Buur, Jacob, Ankenbrand, Bernt and Mitchell, Robb

2013 Participatory business modeling. CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 9:1, 55-71.

Buur, Jacob and Beuthel, Marie Rosa

2013 Skilled Toy Train Discussions about Business Innovation. Proceedings of the Participatory Innovation Conference: PIN-C 2013. Melkas, H. & Buur, J. (red.). Lappeenranta University of Technology, s. 31-35 (LUT Scientific and Expertise Publications.

Buur, Jacob and Gudiksen, Sune

2012 Innovation Business with Pinball Designs. International Design Management Research Conference 2012 – Boston, USA.

Buur, Jacob and Larsen, Henry

2010 The Quality of Conversations in Participatory Innovation. CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, 6:3, 121-138.

Buur, Jacob and Mitchell, Robb

2011 The Business Modeling Lab. Proceedings of the Participatory Innovation Participatory Innovation Conference 201 5, The Hague, The Netherlands http://sites.thehagueuniversity.com/pinc2015/home 8 Conference 2011, pp. 368-373.

Buur, Jacob and Sitorus, Larisa

2007 Ethnography as Design Provocation. In Proceedings of the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference, pp. 146-157. https://www.epicpeople.org/ethnography-as-design-provocation/

Brinkmann, Svend

2014 Doing Without Data. Qualitative Inquiry. Vol. 20, No. 6, 720-725.

Efthekhari, Nazanin and Larsen, Henry

2012 Tangible Business Modeling in Customer Orientation. In proceedings of the Continous Innovation Network Conference 2012.

Gunn, Wendy and Donovan, Jared

2012 ‘Design anthropology: An introduction’, in W. Gunn and J. Donovan (Eds), Design and Anthropology, Farnham: Ashgate, 1-16.

Ingold, Tim

2014 That’s enough about ethnography! HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 383-395.

Marcus, George and Fischer, Michael

1986 Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Science. University of Chicago Press.

Moeran, Brian

2007 From participant observation to observation participation: anthropology, fieldwork and organizational ethnography. Creative Encounters Working Papers.

Otto, Ton and Smith, Rachel Charlotte

2013 Design Anthropology: A Distinct Style of Knowing. Design Anthropology. In W. Gunn, T. Otto and R. C. Smith. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1-29.

Powell, Michael G.

2016 Media, Mediation and the Curatorial Value of Professional Anthropologists. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference, pp. 2-15. https://www.epicpeople.org/media-mediation-curatorial-value-professional-anthropologists/

Smith, Rachel Charlotte and Kjærsgaard, Mette Gislev

2015 Design Anthropology in Participatory Design. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal – IxD&A, No. 26, 2015, pp. 73-80.

Wolcott, Harry

1995 The Art of Fieldwork. Altamira Press.

Yanow, Dvora, Ybema, Sierk and van Hulst, Merlijn

2012 Practising Organizational Ethnography, in G. Symon and C. Cassell (eds) Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, pp. 351-72, London: SAGE

Ybema, Sierk, Yanow Dvora, Wels, Harry and Kamsteeg, Frans

2009 Studying everyday organizational life. In Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexities of Everyday Life, edited by: Ybema, S., Yanow, D., Wels, H. and Kamsteeg, F.