Sustainability & Ethnography in Business Series, Mike Youngblood, Editor

When we think of technology and innovation responses to global warming, we tend to imagine grand solutions that address the problem on a massive scale. For many ethnographers, designers in industry and other solution seekers, this makes the challenge of sustainability daunting, something we can’t imagine pursuing in our day-to-day practice.

However, we can make a significant impact with relatively simple solutions, especially if they are tailored to local lifestyles and take into account habits, routines, practices, requirements and expectations of the people. This was the approach of the DriveGreen project, which was launched in 2014.

The initial plan for DriveGreen was to prepare a simple and affordable smartphone app for drivers of passenger cars. It was supposed to operate much like Toyota’s iPhone app A Glass of Water, which determines and visually communicates how economical, safe, and environmentally responsible our driving is. We were encouraged by research showing that tools like this can actually save up to 10 percent of fuel and reduce a similar proportion of CO2 emissions caused by traffic (Barkenbus 2010; Tulusan et al. 2011).

The process seemed straightforward. Less than a year into our three-year project, however, we realized we needed to change the initiative entirely. Why?

Our 12 member team, which included anthropologists from the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, engineers from the University of Ljubljana’s Faculty of Electrical Engineering, and experts in the development of telematics solutions for commercial vehicles from CVS Mobile company, began with ethnographic research in five European cities—Ljubljana, Belgrade, Budapest, Newcastle, and Durham. Our goal was to identify how to customize the user interface to various locations, people’s needs, culture-specific uses of passenger vehicles, and so on. But when we began to understand how people live their lives and what motivates them, we realized we needed to do more than just customize the UI.

People before Solutions

We learned immediately that ethnography could have a much more significant role in planning and designing people-friendly and environmentally responsible technology solutions than we initially thought. Our ethnographic research findings cast more and more doubt on the original idea detailed in our project application.

For one thing, people we spoke to constantly reminded us that the cost of fuel is not extremely important to drivers of passenger cars. The fact that we can significantly reduce fuel consumption and annually save a few hundred euros or dollars, simply by driving calmly and without breaking or accelerating sharply, does not in itself compel people to drive differently. The savings that could be achieved on a daily level are relatively low, and drivers are often in too much of a hurry to keep track of these minimal savings by properly accelerating, turning, and braking—all while racing with time to finish work, get the kids from school, or make it to their next activity.

Similarly, our research showed that data on greenhouse gas emissions is not an effective motivation either. In the cities where we carried out our studies, people were worried about CO2 emissions, but mainly on a declarative level. Information about the amount of emissions produced while driving was too abstract for them to significantly change their driving style.

In addition to these two big challenges, people consistently reminded us that the use of mobile phones in vehicles is extremely dangerous. We knew this, of course, but we still tried to use the phone to measure the driving style, and to modify the user interface so that the driver would be made aware of their driving style using sounds instead of on-screen animations. Using the application this way might be somewhat safer, but our research participants were right—the phone would still disturb the driver with its beeping, jingling, and buzzing.

In short, our development plan collapsed almost entirely less than a year after the start of the three-year project. We had to start again and this time target people instead of technology. We had to figure out what motivates people to change their driving habits and mobility practices. In this, ethnographic field research continued to play a crucial role. New horizons started to open up to us soon after we launched our first field study in Ljubljana.

Redefining the Opportunity

Interestingly, despite their devotion to driving, the people we spoke with described their daily errands and commutes as a source of anxiety and frustration—but they still got in their cars every day, and then they swore, gestured, and honked, to express their anger and rage (Podjed and Babič 2015). This seemed to us to be an opportunity.

Rather than trying to change the way people drive, what if we could incentivize them to not get in their cars at all—at least some of the time? If we could convince people not to drive just in the morning time, for example, that would save much more fuel than just encouraging more efficient driving. Furthermore, the users of our application would get angry less often and would move their bodies more, which would also affect their health and well-being.

With this starting point in mind, we prepared a new concept for a smartphone app that shows us how much we move in the city on a daily, weekly, monthly, and annual basis. Driving a car per se became of secondary importance to our solution. In the app, driving is marked with the color red (which is widely interpreted to have a negative connotation, especially in the context of driving), while other, more environmentally responsible ways of movement have more positive connotations.

In a shift from the initial name of the project, DriveGreen, we gave the app a name that has nothing to do with driving; it is called ‘1, 2, 3’, which indicates that it is time to start an activity (“1, 2, 3 … now!”). It also refers to three steps we can take to a sustainable future—first for the individual, second for the city, and third for the planet (see Figure 1). The most important thing is that the name is easy to recognize and spell in different countries and languages—“ena, dve, tri” in Slovenian, “one, two, three” in English, “egy, kettő, három” in Hungarian…and so on.

The app uses sensors in the phone to detect whether we are walking, running, cycling, using public transport, or driving a car, and it visualizes the completed activities on the ‘action wheel’ (see Figure 2). Under it, people can see their personal results and can compare it with the average of all the other users in the city so they can determine whether their day was above or below average. They can also view the total distance and the savings in CO2 emissions achieved by using environmentally friendly ways of movement, but this calculation is a background feature, not a prominent one, a choice based on our realization that greenhouse gases are quite abstract and less successful as a motivational factor for most people.

The main innovation of the ‘1, 2, 3’ app is the social dimension that connects people to work together toward a common goal. Since this goal needs to be more clear, accessible, and concrete (cf. McGonigal 2011) than emissions data, we have designed the campaigns so that people can compete against another actual, known person; for example, against the Mayor of Belgrade, a movie star from Budapest, or the Slovenian President. The challenge for the celebrity is to walk, run, cycle, or use public transport at a rate higher than the city’s average—at the same time that other people in the city work to raise that average. If the celebrity does not beat the city average, she or he has to donate a certain amount of his or her own funds for the reconstruction of infrastructure or the renewal of bike trails in a city park. We called this cooperative-competitive principle ‘indirect microdonations’ because every walked or cycled kilometer or mile counts, but the app users themselves aren’t required to contribute any funds for the improvement of transport infrastructure.

Designing for Local Relevance

Ethnography proved to be important for the development of the app for yet another reason. In each city where we carried out the research people have unique sets of deeply rooted habits and practices. These habits are associated with socio-cultural and political-economic factors, as well as geographical characteristics, climate conditions, existing infrastructure, state of the rolling stock, and so on. We would not have been able to get to know and understand all of the factors without doing the field research in different locations, talking to people, observing their habits, using public transport, taking the car to the mall, or putting on a helmet and heading to the main square by bike. We had to discover how we could successfully promote sustainable mobility in each place—one size would not fit all.

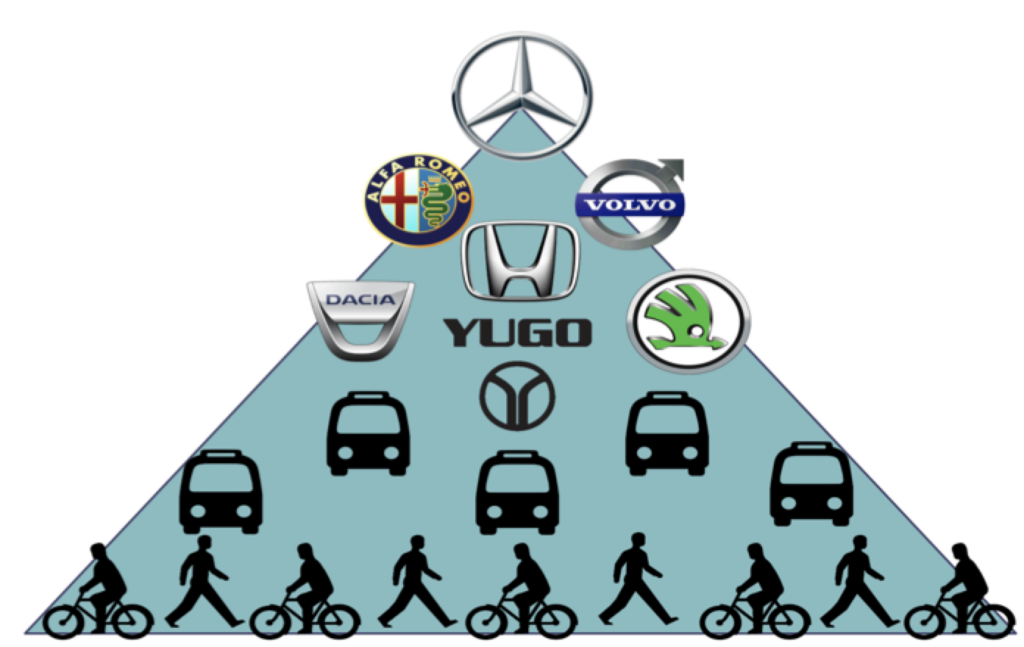

It turned out, for example, that in Belgrade cycling and walking are a lot harder to promote than in the other places that we researched, since there are very few bike lanes and the terrain is relatively diverse. However, an even more important factor that affects peoples’ choice of transport there is a pyramid of social stratification, which works on the principle that “you are what you drive”:

On top of this symbolic formation there is (still) a big black German car brand; on the level below are other foreign car brands; somewhere in the middle are the vehicles which the Serbs consider as ‘ours’ (cf. Živković 2014), including the legendary Yugo, which used to be produced by the Serbian company Zastava. Still lower in the pyramid are people who use public transportation—buses, trolley buses and trams—and the lowest level is populated by pedestrians and cyclists. The locals have repeatedly explained to us that people do not use bicycles due to the prevalent opinion that only “the poor” cycle, meaning those who cannot even afford bus fare, let alone a car (Babič and Podjed 2016).

Achieving sustainable mobility and turning the pyramid upside down is a great challenge in such an environment. It appears that such a reversal will not be achieved through a universal solution based on the one size fits all principle, something we could just transfer from Amsterdam or Copenhagen. Instead we will have to take into account how the people of Belgrade think and customize the app accordingly.

A Detour on the Highway to Sustainable Mobility

The results of the first tests done in Ljubljana indicate that the current version of the 1, 2, 3 app is still rather weak in several technical respects, especially in automatically detecting the way people move. However, the feedback received from the test group of users, derived through a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches—from eye tracking to the information collected through questionnaires and interviews—is also encouraging. People like the concept of ‘indirect microdonations’ and are interested in individual and collective health and wellbeing challenges. It is confirming the fact that a detour on the way to sustainable mobility was the sensible thing to do, to break up the original development plan and to allow people to take the initiative.

Perhaps the most relevant output of the project was a realization that the “bottom up” approach, which is closely connected to anthropology and ethnography, can significantly contribute to the development of new solutions for promoting sustainable lifestyles. Findings from the field helped the researchers and developers—and hopefully also the first users—realize that design for sustainability doesn’t have to change the entire world at once. Instead, we can have cumulative impact through relatively small, meaningful, lifestyle interventions which might even not be directly connected to reducing emissions of greenhouse gases.

References

Babič, Saša & Dan Podjed. 2016. Vozila in stereotipi: Primerjava Ljubljane in Beograda. [Vehicles and Stereotypes: A Comparison between Ljubljana and Belgrade.] Glasnik SED 56(1/2): 74-84.

Barkenbus, Jack N. 2010. Eco-driving: An Overlooked Climate Change Initiative. Energy Policy 38: 762-769.

McGonigal, Jane. 2011. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. London: Jonathan Cape.

Podjed, Dan & Saša Babič. 2015. Crossroads of Anger: Tensions and Conflicts in Traffic. Ethnologia Europaea 45(2): 17-33.

Tulusan, Johannes, Lito Soi, Johannes Paefgen, Marc Brogle & Thorsten Staake. 2011. Eco-Efficient Feedback Technologies: Which Eco-Feedback Types Prefer Drivers Most? In: 2011 IEEE International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. Pp. 1-8.

Živković, Marko. 2014. Little Cars that Make Us Cry. In: David Lipset & Richard Handler (eds.), Vehicles: Cars, Canoes, and Other Metaphors of Moral Imagination. New York & Oxford: Berghahn. Pp. 111-132.

Dan Podjed, PhD, is an applied anthropologist from Slovenia, working at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts and teaching at the University of Ljubljana. He has led several interdisciplinary projects, and has been involved in development of many ethnography-based IT solutions. Since 2012, he has been coordinating the Applied Anthropology Network of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA). He is the founder and organizer of Why the World Needs Anthropologists international symposium, annually organized since 2013.

Related

Sustainability and Ethnography in Business: Identifying Opportunity in Troubled Times, Mike Youngblood

Navigating Relativism and Globalism in Sustainability, Caroline Turnbull

Putting Mobility on the Map: Researching Journeys and the Research Journey, Simon Roberts

0 Comments