Ever heard about the “the turning of the bones” in Madagascar?

Once every five years or so, families get together for a rambunctious gathering at their ancestral crypt as they exhume the bodies. It’s a very lively affair – family members share recent news with the deceased, ask for advice and blessings, and even take them for a little dance…

Now, for many people, the thought of waltzing with the late Great Aunt Ingrid and asking her opinion of your new fiancé is downright inconceivable. But that’s not where our inhibitions begin. Let’s face it: most of us won’t even talk about “it” until we absolutely have to. It’s not just that death is not often thought of as appropriate dinnertime conversation. It’s more than that. Talking about death is stubborn and culturally rule bound – much to our detriment, it turns out.

We’re in an age where there’s an abundance of human-centric services; a wealth of ‘smart’ things – products, apps, wearables, initiatives – that make our lives easier and respond directly to our needs. Funeral practices, however, are still positively antiquated. Rites have a desultory chill and rigour that hardly does justice to the individuality and flair of the lives people have led.

Could it be that these cultural rules are hindering happiness and progress? If death, for all of us, is as certain as taxes, then why not explore our actual needs around it? If we cannot avoid it, why not make it better?

So that is exactly what we set out to do.

We set out to launch the Re.Designing Death Movement to build and nurture new opportunities for innovation around death and dying. The seeds of this movement were sown by the likeminded and equally frustrated designers and researchers in our marketing research and innovation agency, Point-Blank International. As we began to research the literature, informing ourselves, starting conversations among friends and family, and generally testing the waters, we found it wasn’t just our fixation. There is, it seems, established curiosity and interest and enough a fertile ground for an ethnographic study of death, dying, and beyond. And as serendipity would have it, long time colleague and friend Cat(riona) Macauley, then director of Dundee University’s MSc in Design Ethnography, was keen on dabbling in death with her students, and so a collaboration was born. The students made Berlin and Dundee their field sites and, with Inga’s help, carefully structured an ethnographic study of death.

Ethnography, as a method, is unrivaled when it comes to the exploration of social and cultural practices – especially those that resist easy entry points. The study was framed around the traditional players in the death economy and culture: undertakers and ministry, and those in the growing palliative care and hospice fields. The students listened to the assumptions, limitations, and dreams of change in these structural elements of the death industry. Visiting workplaces and talking informally, the students learned that the field is marked by the classic unquestioned acceptance of cultural continuation. And they saw that if you scratched the surface, few people would like to die in the ways the death narratives are told. Through word of mouth, individuals came forward who had themselves begun taking up the cry to innovate around the end of life. These included clothing designers for the resting garments, home deaths, sea burials, natural cemeteries, and surprising other innovations. In the process the students bumped up against government laws and regulations, separating people from desired innovation by a fine line, as we learned.

The design and ethnography components of the study dovetailed neatly with the movement when the students created workshops and open houses as safe environments that nurtured dialogue and introspection about death. Design also came in handy when sculpting the ethnographic findings, discussions, and insights from those workshops into information that is sharable, digestible, engaging, and always “user-centric” for the Re.Designing Death community. Our goal was to let people internalize the ethnographic findings as they were woven into the workshop design and into assorted other presentations so as to compel them to rethink the hard held cultural rules that surround thoughts of dying. With a growing sense of safety that emerges as people make the uncomfortable familiar, we hoped to use the Re.Designing Death movement to stimulate change.

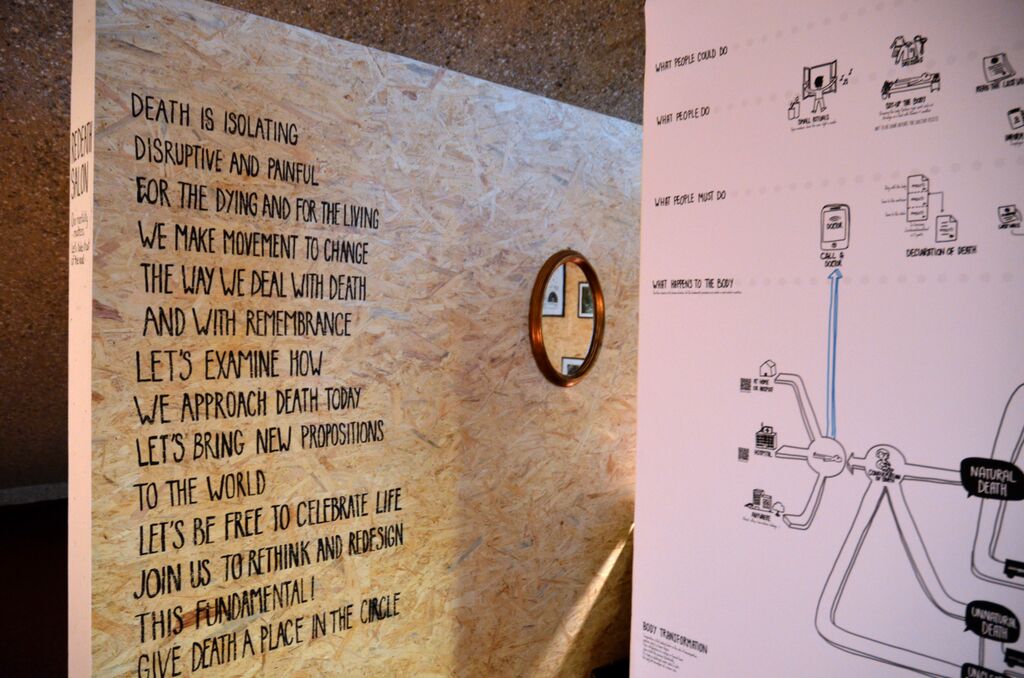

Journeying to Berlin from Scotland for the appropriately named “hothouse summer”, our intrepid student ethnographers set out to collect stories from the field. Our hosting of a two-day drop-in workshop at PBI as part of Berlin Design Week saw them armed with sharpies, post-its and several kilos of LEGO, beckoning visitors to enter a world that was freed from the customary directionality of life. They were invited to reflect on thoughts of others and self, and to consider their end of life visions and wishes as well as to write open letters to ‘Death’.

Of all the prudent and unanticipated learnings that came from the ethnographic research and the discussions and introspections from the workshops, there are two we’d like to share with you here.

The core learning for us was that our initial instinct was a bit off. People are actually quite happy to talk about death. It’s just that they need the right environment and perhaps some gentle encouragement to do so. It seemed that once the initial barrier was breached in an open and congenial manner, talking about death wasn’t nearly as difficult as we’d thought.

We witnessed this first hand at the Berlin Design Week drop-in workshop. To our genuine surprise, the people we spoke to talked at length of what they themselves would consider a ‘good death’ and how they think they would like to be remembered. A group of strangers, having met only minutes before, shared intimate stories and personal fears with each other. We saw their discernible catharsis as they ‘thought out loud’. Most of them hadn’t really considered their deaths before and they were actually smiling as they did. It seemed that talking about death and last wishes can not only prepare you on a practical level – it can be truly liberating to accept your mortality and uplifting to share this with other people. And not just when you’re running out of time.

As a direct result of this observation, our strategic designer and movement leader Virginie Gailing teamed up with mortician-in-training Lea Gescheidel to develop a conversational card game. The objective is to facilitate this all-important dialogue – allowing people to explore their own wishes and needs around death.

In spring 2015, Virginie and Lea took their game to the Lift Conference for a test run, where they constructed a pop-up death salon right in the Foyer, inviting strangers to play together. Over two days they played with more than 150 engaged and enthusiastic people who offered a plethora of new observations and stories to work with.

The second and, in our opinion, most intriguing learning from this venture was that the students’ research triggered in itself an organic innovation process. Through the ethnography, the movement took on a life of its own as interview respondents became active members of the movement and added to its momentum. They built networks of concerned and interested people who could make direct use of the students’ findings. As researchers, we often lament how much of our work is left to the wayside because of a lack of resources and people to carry it on; here we witnessed first hand the power of ethnography not just to unearth insights, but to become itself a driver of growth and change.

It is worth noting that Berlin itself is something of an incubator of change, known as one of the startup capitals of Europe, filled with the minds of the inspired, aspiring, and uninhibited. So the locale became its own startup for the organic innovation process that was set in motion by simply putting people together in safe ways. It was a case study in challenging the taken for granted, and moving on directly into societal transformation.

Our four Dundee design ethnographers (the students) worked with more than 100 respondents during their time with us and painstakingly transcribed their interviews at the pace of a daily newspaper publisher. Their research formed the foundations of our movement’s subsequent actions. Two years on, the Re.Designing Death movement is a self-driving dynamo, as members of our community continue to host talks and workshops at conferences and events. Thanks to our ethnographic groundwork, we’ve been able to find out what challenges really needed tackling and get a dedicated community on board.

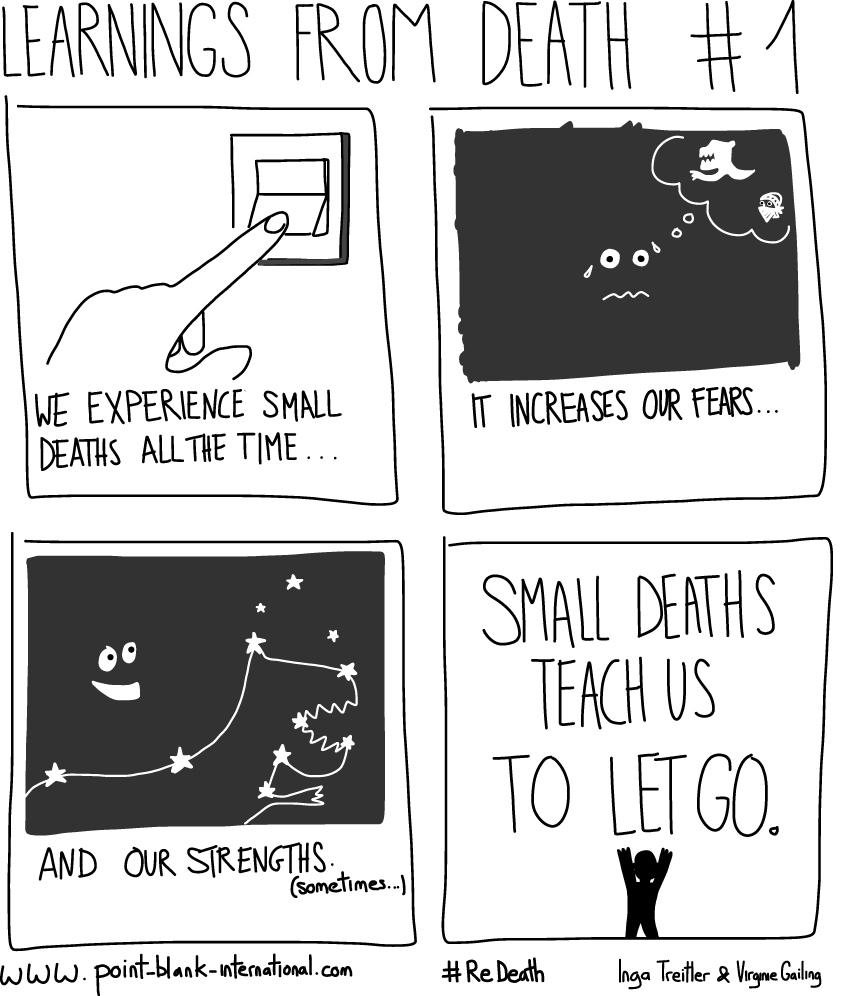

With this solid foundation of research at our disposal, we’ve been continuing to produce both large- and small-scale projects. Virginie teamed up with Inga to craft a series of graphic shorts called “Learnings from Death” illustrating themes culled from the thicket of ethnographic findings.

We also have hosted a ‘DIY funeral’ workshop at the Re:publica conference which Cori then took to Leeds as part of the age-friendly smart city initiative. The focus of this workshop is to enlighten, inform and inspire participants that there is a lot that one can do to commemorate a loved one after they pass – it doesn’t have to be ‘traditional’.

And so our quest continues: to get people to talk about death, but not only about death; about the joys that accompany the comforts in choosing the voyage rather than being carried unquestioningly by antiquated laws that are no longer apt. The flexibility of culture was tested by our team and it was found to be less stubborn than had been assumed. Death, and even talk of death, is not after all a taboo, but clearly it takes people into realms where culture provides gentle guidance even if not control.

Our team put themselves to work integrating the methods of ethnography and design in a creative realm that, as we discovered, is ripe for change and begs for innovation.The ethnographers learned about associations, foundations, cafes, insurance, software, apps, wilderness funerals, open sea burials, and so much more. In their interviews and networking, as so often happens in life, they kept learning of other concerns and innovations in and around the end of life.

The stories we heard make dancing with bones feel rather less exotic. Many people want to speak to others about their own mortality, even after they are gone (thanks to the power of the digital). Having taken the risk to test the flexibility of these cultural rules, our role now is to continue to find new ways through ongoing ethnographic endeavors and active design collaborations to bring death happily back into our lives, where it belongs. Come! Cast off your cultural inhibitions. Invite someone living or dead, to take a dance with bones: https://www.facebook.com/ReDesigningDeath

0 Comments