Taking India’s startup capital Bangalore as its field, the paper researches the absence of conventional scale as a potentially positive emic experience for the entrepreneur. The study leverages a mixed methods approach, employing semi-structured interviews with select entrepreneurs, employees, investors, advisors, and staff from startup-incubators, participant observation at both startups and startup-incubators, textual analyses of business literature, semiotics of popular culture as well as auto-ethnographic reflection by the authors themselves on account of having co-founded a company in Bangalore in 2018, therefore establishing their positionality as ‘an-other’ (Sarukkai 1997, 1408), by ‘thick participation’ (Samudra 2008, 667). The authors examine the current assemblages within the startup ecosystem, to demonstrate that even the dominant and conventional notions of scale have begun to demonstrate multidimensionalities. At the same time, the authors advocate a case for tethering at different points of the scalar continuum as an alternative model of entrepreneurship. The authors share ethnographic evidence from their research on startups that are increasingly beginning to explore potentialities and innovation at the existing point of the scalar continuum through an exercise in consolidation and tethering. Finally, the authors advance the proposition that a quest for value is not necessarily resistant to scale, and concomitant streams of nonscalability as lines of flight existing along the periphery of incumbent structures, always carry the possibility to escape and thus, create potentialities for creativity and disruption.

Keywords: Scale, Startups, Entrepreneurs, Interscalarity

‘The facilitation under the Startup policy is intended for only technology based startups, i.e. one that creates a technology-based service or product or uses technology for enhancing functionality or reach of an existing product or service’ (Startup India 2020).

‘[A technology startup is]… an entity working towards innovation, development, deployment, and commercialisation of new products, processes, or services driven by technology or intellectual property’ (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018).

A TALE OF THREE CO-FOUNDERS

On a pleasant Bangalore summer evening in 2019, is when we first met with Saurav, Varun, and Abhay, the young co-founders of an AI-powered startup focusing on helping children from small-town India improve their spoken English skills. Sipping on masala chai, they recounted how it was the near-debilitating insecurity they felt when at university, around their own inabilities to converse in English as fluently as their city-educated classmates could, that spurred them to found their startup, which we will call Chalk Test.

‘Our shared, personal experiences,’ Saurav explained, gesturing towards his co-founders, also classmates from university, ‘have shaped the direction in which the three of us want to move our company. The problem of not being able to speak in English and thus suffer a significant erosion of confidence, is severe. Importantly, it is not so much a function of the family’s income, as it is about the resources and opportunities which children from smaller towns and villages lack.’

We talked about Bangalore’s thriving startup environment. The city continued to be celebrated as the ‘top tech startup hub’ in the country, and for being amongst the ‘top 3 cities globally for …[the]… launch of tech startups’ (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 12). The modest offices we were in was part of a leafy neighbourhood emblematic of the city’s reputation, throbbing as it was with ambition, evident from the several many, unmissable startup address plaques and signages, busy dive bars, hip gastropubs, and bustling hole-in-the-wall restaurants.

‘There is a lot of noise in the startup community,’ Saurav continued. ‘Everybody talks about funding, the next million, and being featured in the media. All of this makes you question your core beliefs and assumptions. We need to be careful not to be influenced by the noise.’ Vaibhav joined in, ‘Social purpose must be balanced with commercial sustainability and scale. We have to manage two contrasting aspects: creating impact and making money. We have not been able to find the balance yet. We also have to pay our staff and team of freelancers. That is why we have plan B, to focus on non-core revenue which can cover expenses and decrease burn. We need specific skills to scale. Plan B helps us buy them. That said, we have to think about how we can monetize the app and breakeven soon.’ This served as a cue for Abhay, the relatively quieter one of the three co-founders. ‘We have hundreds of positive testimonials from children who have used the app,’ he tabled. ‘This is real impact, and this is what keeps us motivated. After all, an increase in a student’s confidence is success for us. Increase in speaking time and frequency are metrics we have begun to track. They show if the student has begun to speak her mind.’ ‘We see no difference between a social and a for-profit enterprise,’ quipped Varun. ‘Adding social as a term to an enterprise essentially gives us a framework for decision-making. The fundamentals of business are the same. What I am saying is that we need to work on our metrics, create impact, and capture the wider market.’ ‘We have to find a balance between cause and commerce in our metrics and measures as well,’ summarized Saurav. ‘We do not want to be romantic social entrepreneurs. For while we know that education is a slow and hard business, we fear that we may just be running out of time.’ (Field Notes Extract 2019)

INTRODUCTION

Our research has its roots in a project commissioned by one of our clients, a Bangalore-based innovations incubator which we will call InnoCubator, that sought to explore how certain early-stage ventures in its portfolio could scale-up. Yet more importantly, even if implicitly, it wanted to understand what scaling-up really meant, outside of the unidimensional, le manuel scolaire perspective of growth as defined in terms of financial, market and customer metrics. To us, the project-ask was, in and of itself, a notable point of departure. A startup incubator going beyond traditional metrics and seeking an alternative grasp of scaling-up was uncommon, to say the least. For as Tsing (2019, 143) hauntingly advances, while alluding to scale as an exercise in precision, ‘there is something disturbingly beautiful about precision, even when we know it fails us’.

Tsing warns us of the dangers of a relentless pursuit of scale-making where ‘bigger was always better’ as one anchored in expansionism of the kinds which ignores ‘meaningful diversity’ (2019, 145-146). Our ethnographic encounters with entrepreneurs in Bangalore over the summer of 2019 demonstrate a remarkable grasp on their part of Tsing’s cautionary note. As in the case of the co-founders of Chalk Test, our conversations were invariably peppered with references to scale and its concomitant notions of scaling up and scalability, almost in the sense of a Durkheimian social fact. Yet just as our three young protagonists simultaneously acknowledged and sought to dialectically negotiate such hegemonic and unidimensional narratives through arguments anchored in alternative ‘plan B revenue streams’ which allowed them to focus on ‘impact’, and articulations of the need to balance ‘social purpose’ with ‘commerce’ (Field Notes Extract 2019), so did the other entrepreneurs, academics, and industry experts we engaged with.

As our study eventually showed, a small but growing breed of entrepreneurs, investors, and incubators in India was beginning to view failure to scale in the conventional sense, as advancing a Deleuzian glance at an entrepreneurial becoming, and an opportunity to pivot to alternative goals and means of engendering value. Scale was being at once resisted and negotiated to incorporate the non-scalable through inter-scalar articulations and balance, as in the case of our three Chalk Test co-founders, in the sense of assemblages comprising ‘plan B’ and ‘non-core’ activities on one hand, and ‘real impact’, ‘specific skills’ and ‘getting the technology right’ on the other hand. Or as a seasoned academic we spoke with, pointed out:

There is no definition of what constitutes scale. Each entrepreneur should decide the framework and time period to achieve scale based on his or her priorities. Everyone need not become a unicorn or float an IPO. Keeping your head above water for a long period of time may also be sufficient for someone. (Field Notes Extract 2019)

Carr and Lempert (2016, 8-9) tell us that a meaningful ethnographic approach to understanding scale situates it as ‘a practice and process before it is … [a] … product’. Taking India’s startup capital Bangalore as its field, this paper researches the absence of conventional scale as a positive emic experience for the entrepreneur, undergirded by the affective imaginaries of passion, independence, and perseverance. The study leverages a mixed methods approach, employing semi-structured interviews with select entrepreneurs, employees, investors, advisors, and staff from startup incubators, participant observation at both startups and startup incubators, textual analyses of business literature, as well as auto-ethnographic reflection by us on account of having co-founded a company in Bangalore in 2018, therefore establishing our positionality as ‘an-other’ (Sarukkai 1997, 1408), by ‘thick participation’ (Samudra 2008, 667). In doing so, the study posits that the problematic playing out in India’s entrepreneurial zeitgeist is not necessarily a summary rejection of notions of economic or financial value, but a nuanced adoption of balance incorporating recognised key performance indicators (KPIs) of ‘bigger, faster, easier, broader’ (EPIC 2020), alongside alternative metrics, goals, and measures of value.

In order to develop a deeper understanding of interscalarity, we drew analogous inspiration from Susan Philips’ ethnography of how ‘legal activity is interscaled in [Tongan] higher and lower trial courts’ and in doing so, naturalizes the institutions and their ideologies (2016, 112). She asserts that ‘scaling is, after all, a cultural and a semiotic phenomenon’ and is characterized by an interdependence of elements, whose intertwining is taken for granted (2016, 113). Philips outlines that the higher and lower courts are intentionally maintained at distinct levels of scale to ensure relativity or ‘the scalar antinomy of “higher” and “lower”’ on one hand, and conceptual coherence on the other (2016, 115). This multidimensionality of scale, here expressed as seriousness of the case, plays out along elements such as space (bigger courtrooms), time (longer trials), actors (senior judges), enforcement (of procedures and evidence) and media (both Tongan and English languages being used in the higher courts). The conceptualization and enactment of these hierarchies of scale had its roots in imperialist undertakings, exported by European colonialists as a way of managing complexity and conflict. At the same time, there was a becoming of interscalarity as it continued to get influenced by local Tongan circumstances. Philips identifies five interdependent dimensions which distinguish as well as integrate the higher and lower courts to reinforce the scale of seriousness. These dimensions (2016, 121) encompass cultural phenomena including social identities of the key actors (judges and magistrates, plaintiffs and lawyers), privileging of procedure and documentation, use of language (geopolitical and translocal influences of English on production of activity), length of time spent (on evidences and amount of talk), and space of jurisdiction (area of authority, geographical locations, demarcated physical space, and language choices again). In this manner, Philips advances a compelling argument for analysing scale as a social construct, and understanding the cultural aspects that are immanent in its naturalization. Another key insight which can be drawn from the study is that both higher and lower levels along a continuum need to be nurtured to maintain the function of scale. Situating our research in light of Philips’ study informed our areas of enquiry. Thus, the social phenomenon of scale as conceived and institutionalized in the startup ecosystem in Bangalore entailed an analysis of multidimensionality. Carrying this notion forward, we defined dimensions or assemblage-constituents as primary actors (entrepreneurs, investors, academia, incubators, mentors), procedures (policy documents, funding eligibility guidelines, incubation competitions), language (media discourses), time (invested in evidence building and success narratives) and space (investments in physical capacity, geographic spread of hubs and startups). This specifically elucidated the scope for review of public culture, as we studied varied texts including government startup policy documents, annual reports on the ecosystem, and published interviews.

Furthermore, analysing these narratives within the paradigm of interscalarity yielded distinct areas of ethnographic enquiry. Our principal research question was to interrogate the emerging dimensionality of scale, as it appropriated and absorbed other institutionalized or existing narratives in its fold. As we have noted earlier, the growth of the startup ecosystem in India did not just yield materialization, in the shape of unicorns, funds and technology, but also sought to achieve the state’s priorities of job creation, women empowerment and the development of smaller cities and towns. Second, we asked whether the potentiality of scaling as ‘taking wings’ or ‘achieving escape velocity’ presents a risk of untethering, in the sense of a weakening of the very foundations of the climate of innovation which the startup ecosystem seeks to thrive in (Startup India 2020). We have observed that scale was increasingly getting entrenched as a qualifier or an entry barrier to participate in the startup ecosystem, be it in terms of the stage of funding (with an increase in late-stage investments), the archetype of the startup founder or entrepreneur, and even the requirement of innovative technology solutions for the realization of social impact. And lastly, we sought to understand if the binary of tethering could offer another field of possibility, where entrepreneurs chose to either entirely opt out of the conventional projects of high scale, or continue to negotiate it by concomitantly pursuing desires, in the sense of alternate value.

While our research is situated in India, it can be subsequently leveraged for additional comparative studies in other countries, for governments, funders, and organizations in their broader project of supporting entrepreneurship and innovation. Grounded thus in the EPIC community’s aim of using ‘ethnographic principles to create business value’ (EPIC 2020), we intend for the study to realise a contribution to the ‘largely missing … [anthropological] … research at the level of new ventures’ (Briody and Stewart 2019, 142) in the sense of a diacritical mark for ethnographic literature on entrepreneurship.

SITUATING OUR RESEARCH WITHIN THE POTENTIALITY OF SCALING

‘Breaking $1 billion is a psychological milestone’ said Hiten Shah, cofounder of several SaaS companies, including KissMetrics, Crazy Egg, and FYI. ‘It indicates that your company is a real force, a business to be taken seriously. It has a cascading effect on the press, investors, and recruitment.’ (Sengupta and Narayanan 2019).

2019 represented a critical epoch for the startup ecosystem in India, with the crossing of significant milestones in the preceding year, and the expectations borne with them. Eight startups had crossed the USD 1 billion in valuation milestone in 2018, and attained the much feted status of a unicorn. The number of new technology startups had seen a year-on-year growth of between 12% to 15%, even as the overall number across the country was expected to surpass 7500 (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 3). The 2018 edition of National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM) report on the ‘Indian Startup Ecosystem’ placed great emphasis on notions of scale as markers of success, with callouts such as the ‘dramatic increase in number of unicorns, resurgence in investments, and rapid growth in advanced technology in startup ecosystem’ (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 3). The report highlighted that the ecosystem was gearing up to attain ‘escape velocity’. Projects of global ‘expansion’ had been outlined as well, with references to Indian-origin startups registering their presence in markets outside India, as well as ‘international startup exchange missions’ setting up bases in the country (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 3). In this manner, and come 2019, conventional definitions of scale had been institutionalized to characterise the success of the ecosystem, be it through growth in numbers, rise in funding, or an increase in the adoption of advanced technology. An additional manifestation of scale was seen in the projection of the archetypal entrepreneur. The aforementioned NASSCOM report for example, suggested that a successful entrepreneur was likely to have a strong educational background (as having an engineering, MBA, MS, or PhD degree) as well as prior corporate work experience (of five to ten years) implying better networks and skills (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 59).

The year 2018 had witnessed another key trend where, while there was an increase in the average funding per deal (by 144%), most of it was directed towards mature startups requiring late-stage investments. This clear preference for scale had led to a year-on-year decline of 18% in funding for seed stage deals. In fact, Debjani Ghosh, the President of NASSCOM, had expressed her concern at the probability that without protection at the seed stage, innovation was bound to get impacted (Variyar 2018). Yet at the same time, a rising heterogeneity in the landscape had also been noted, expressed in terms of the increasing proportion of women founders, creation of direct and indirect jobs for the economy as well as the emergence of Tier 2 and 3 cities in India as startup hubs (NASSCOM Zinnov 2018, 59).

For our research, we chose Bangalore, the busy capital of the southern Indian state of Karnataka and the country’s Silicon Valley, as our field. Officially now known as Bengaluru, the city enjoyed (and continues to enjoy) the position of being not only the primary but also the fastest growing startup hub in India. In 2018, Bangalore was home to one-fourth of the total number of technology-startups in the country. The city was the fulcrum for the Karnataka Startup Policy 2015 – 2020, which sought ‘to give wings to startups in the state through strategic investment & policy interventions by leveraging the robust innovation climate in Bengaluru’ (Startup India 2020). Although limited in its scope to technology-led startups alone, the policy’s goals were reflective of the varied aims that a scaling-up of the ecosystem could facilitate. By advocating the growth of twenty thousand technology-based startups in Karnataka, the state government’s goals were effectively looking at the creation of 1.8 million jobs, galvanizing a startup funding investment of INR 20 billion, and generating at least twenty-five innovative technology solutions in areas of public welfare, such as health, food security, clean environment, and education (Startup India 2020). In this manner the city of Bangalore, as an assemblage of actors, policies, spaces, and media, offered an inimitable opportunity to build ethnographic evidence for developing an epistemology of the implications and perceptions of scale in entrepreneurship.

Subsequently, our ethnographic enquiry leveraged participant observation as well as semi-structured interviews in the manner of ‘a series of friendly conversations’ (Spradley 1979, 58). Most of our time was spent at three startups and the innovation incubator InnoCubator, all of them based in Bangalore. The startups were, in a sense, referents of nascent enterprises challenging the standard notions of scale. Apart from Chalk Test, this included a home and office maintenance platform which engaged with local electricians, carpenters, masons, and artisans in an ethical manner, which we will call Nuedle, as well as a bespoke vernacular language learning and translation services app which employed women from socially and economically challenged backgrounds, which we refer to as Diverstics. The fact that all three were within the purview of the project on scale which InnoCubator had commissioned additionally validated their potential as exemplars of entrepreneurship negotiating dominant scalar narratives.

To establish the subjectivities of scale imposed upon entrepreneurs, and also garner a sense of the alternate Weberian archetypes of entrepreneurs as opposed to those frequently projected and reinforced in public culture, we conducted semi-structured interviews with academics, other entrepreneurs who had realised scaling-up projects, investors, startup advisors, and staff from other established startup incubators and accelerators in not just Bangalore, but also the Delhi National Capital Region, as well as the cities of Mumbai, Kochi, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, and Hyderabad.

Having founded a bootstrap startup in Bangalore ourselves, a year prior to the study, helped serve as a phenomenological anchor during our ethnographic engagements. With due reflexive caution, we have alluded to our experiences in this paper, in the manner of ‘embodied, intersubjective, temporally informed engagements in the world’ (Desjarlais and Throop 2011, 92) rooted in the question regarding, and in confrontations with scale.

THE DOMINANT DISCOURSE ON ENTREPRENEURIAL SCALE

‘India’s startup economy has been booming. The last decade has seen significant activity on multiple fronts including the founding of new startups, amount of funding and number of investment rounds, influx of global investors and startups, development of regulatory infrastructure, global mergers and acquisitions, and internationalization. Entrepreneurial success stories abound. At last count, India had 26 unicorns, with eight new entrants joining the club in 2018 alone’ (Knowledge@Wharton 2019).

Over the meetings and tea-stall hanging out we did with the team of Nuedle, the one emotion we encountered time and again was that of anxiety, stress, and fatigue, all rolled into one. Nuedle had its origins in the challenges which the three founders had faced in getting everyday electrical and woodwork maintenance jobs done when they had moved to Bangalore over seven years ago. Bringing old fashioned relationship-building with local networks of electricians, carpenters, masons, and artisans, to a technology platform serving as a marketplace for home and office maintenance services, had led to early successes, unearthing (in the words of its founders) a ‘big enough problem to solve for’ and a ‘huge market opportunity’ which had ‘delighted the investors’ (Field Notes Extract 2019).

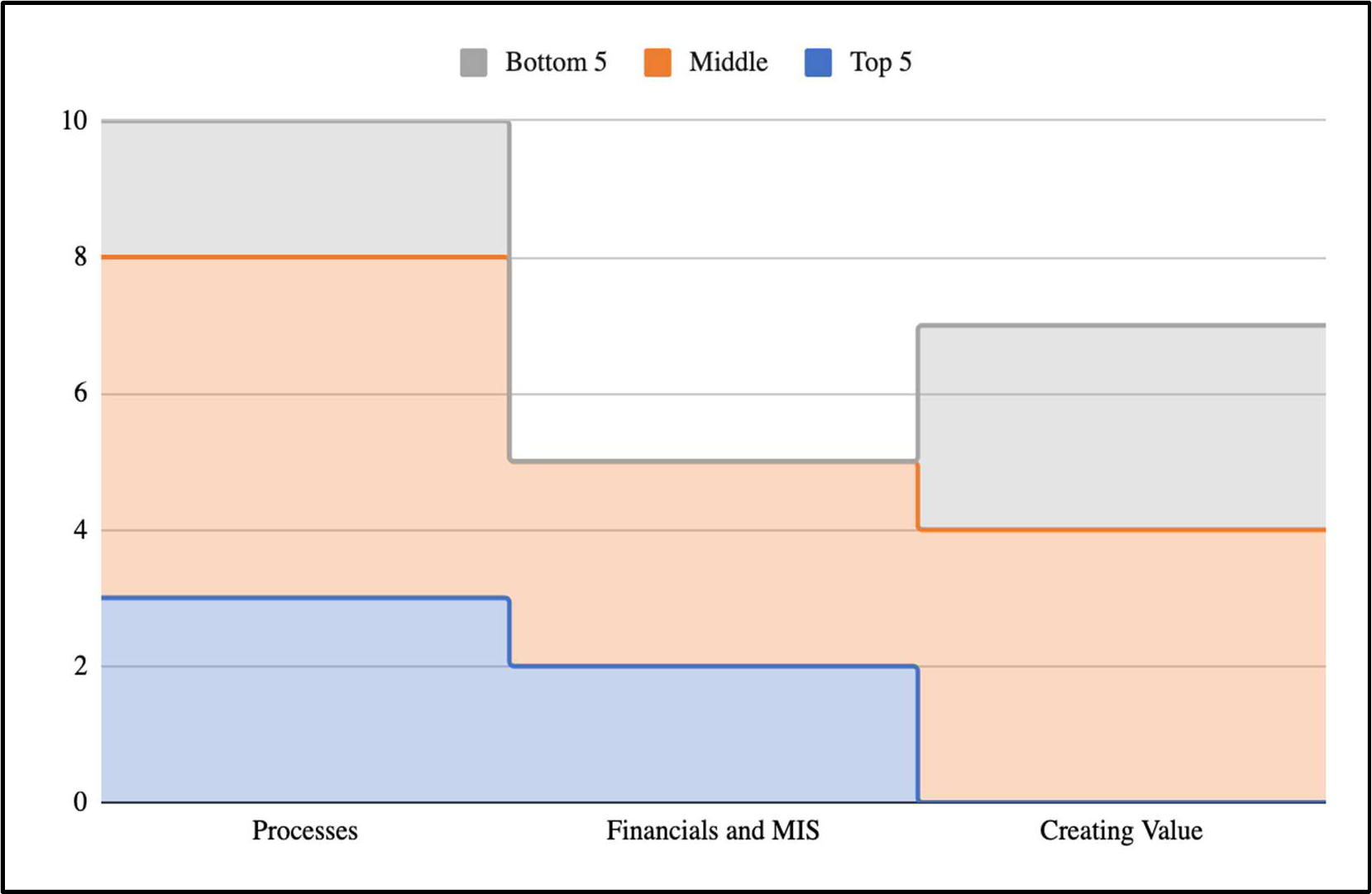

Figure 1 captures the responses to a survey administered by us over the summer of 2019, to Nuedle’s three founders, its thirty-odd employees, a handful of its hundred-plus ‘vocational professionals’, as well as its advisors and investors. The survey asked the respondents to stack rank a list of 22 possible strategic focus areas for the firm, assuming a three-year horizon. Unbeknownst to the respondents, the areas had been categorized, as Processes, Financials and MIS, and Creating Value. The responses were normalised to identify the top five, bottom five and middle range of perceived priorities. Notwithstanding the relatively long time horizon, what is noteworthy from the table is that the top five priorities did not have any representation from the Creating Value category. This remarkable finding was perhaps duly qualified by the Nuedle founders’ callouts, which we noted over the course of our fieldwork, such as being ‘in a reactive, stressful phase for a long time now’, ‘working on transactional, administrative and tactical activities’ because ‘processes are not in place’, being ‘far away from where we had planned to be in 2019’, not having been able to ‘scale up’, and that ‘funding is a major challenge’ (Field Notes Extract 2019).

Figure 1: Survey responses at Nuedle

The example of Nuedle demonstrates how conventional, dominant narratives of scale had come to act in the everyday operations of startups in the manner of Foucauldian power/knowledge subjectivities, thereby shaping their imaginaries. Yet even then, and as our research shows, these discourses were seldom unidimensional. A review of journalistic scholarship, thought papers, and reports on the startup ecosystem in India at the conjuncture of our study, highlights the emerging, negotiated and multidimensional aspects of scale, even if within the dominant frames, as we critically interrogated scalability and scaling-up as lived, socio-cultural experiences on one hand, and studied the assemblages which have contributed to its realisation on the other hand. Rooted in ethnographic enquiry and a review of public culture, we now turn to these narratives as resident within the dominant discourse.

The successful entrepreneur

Our research suggests that narratives in public culture privileged a certain archetype of a successful entrepreneur, even if they did not disregard the multiplicity of their skills and experiences. Distinct social identities are incorporated in the archetype, thereby defining scalability as a factor of the entrepreneur’s educational degree, prior work experience, domain expertise, and even age. Thus, a startup which is likely to scale has been normalised and understood as one which is ‘led by a group of well-educated co-founders with several years, if not decades, of work experience between them’ (Chitnis 2018).

Additionally, the maturity of a given startup ecosystem is described in the form of the rising incidence of fluidity among roles, entrepreneurs-turned-serial entrepreneurs, serial entrepreneurs-turning-angel investors, investors-turned-entrepreneurs and employees-turning-entrepreneurs. These sequences are simultaneously suggestive of another dimension of scale, that is, of successful exits. The evidence for a startup’s scalability is being read as a factor of there being individual entrepreneurs who are likely to ‘produce more successful exits … [for investors and founders] … with their tactical, experiential knowledge and easier accessibility’ (NASSCOM Zinnov 2019). Of note is the singular absence of the word ‘exit’ from the 2018 edition of the same report, making its debut only subsequently. Furthermore, this potentiality of successful exits has also brought more players into the ecosystem, as for example, global and corporate investors.

While the ecosystem has witnessed existing players gaining expertise and moving across roles, it is also beginning to stress the need for building greater diversity within its fold, specifically among first time entrepreneurs. For example, dedicated funds and incubators for women entrepreneurs have been established. We noted however, that these distinct players did not bring about any change in the ecosystem as such, but incorporated their efforts within the existing structures and narratives. This is tantamount to a non-becoming of scale, which does not solve for inherited social inequalities, such as lower representation of women in corporate leadership roles. In turn, this has led to its own implications, as encapsulated below:

‘Women are missing in the Startup India initiative because many women, who start their initiatives, are not in the limelight or mentored professionally. Additionally, when it comes to funding, women are not only scrutinized about how they’d manage their businesses, but also their families in parallel, which isn’t a filter men are put through … Thus women need to break through filters to raise capital and grow their businesses’ (Saxena as quoted in Sharma 2020).

Another example of such a non-becoming, was evident from a discussion earlier this year on women-entrepreneur-focused platforms in a WhatsApp group for entrepreneurs we are part of. One of the members highlighted how endemic gender inequalities are extended to the world of startups, as he shared how at the time both his wife and he left their corporate jobs to pursue entrepreneurship, he was questioned on whether he had done a proper risk assessment while nobody posed this question to his wife. As he noted, many believe that ‘for women … entrepreneurship is ghar+’ (or home+), thereby implying that women are seen as entrepreneurs only after domestic responsibilities have been taken care of (Field Notes Extract 2020). Continuing the thread, another women entrepreneur, who had chosen to set up her own enterprise independent of her family business, shared that ‘..being taken seriously [is a challenge] that resonates’ and that ‘there are days when I think being a businesswoman … is totally pointless … but then the next day is a new day again’ (Field Notes Extract 2020). In this manner, gender as a social identity has been re-territorialized in a Deluezian sense, as both an enabler for entering at the lower end of the continuum of scale, as well as a barrier, for progressing up the spectrum

Technology as an actant

Finally, our study points at how technology as a non-human actor or actant in the assemblage of the entrepreneurial project of scale has also been ‘both changed by … circulation and changes the collective through …[its]… circulation’ (Sayes 2013). Each wave of the startup ecosystem brings about the demand for new business models and the technologies which facilitate them. And while technology itself scales up in the form of deep-tech and advanced-tech-led solutions, it also demands a related scaling by human actors. Each business idea is now pitched as a tech-led business, and technology is hardcoded into the eligibility criteria for a startup to receive policy or funding support. Technology is also incorporated within the themes or areas that solutions are invited for. That said, in having become a go-to-actant for scalability, technology has also created entry-barriers of digital inclusion bordering on the tautological, which entrepreneurs without prior knowledge or experience in technology either struggle to surpass or attempt to negotiate creatively, as in the case of the founder-proprietor of a Bangalore-based training services company we spoke with, who positioned the firm as an ‘innovation and design thinking organisation’ and advertised its social media followers as an attestation of its ‘commitment to and focus on technology’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). An idea without technology is thus relegated to the realms of non-scalability.

Scale begets scale

A review of the government’s policy documents on entrepreneurship and startups, as well as the calls for funding published on its websites reveals the protocols and processes adopted to demarcate measures of success, define eligibility and outline criteria for entry and exit along the continuum of scale. The Karnataka Startup Policy 2015-2020 established three qualifiers for an entity to be categorised as a startup. It needed to be technology-based, registered or incorporated in the state of Karnataka (especially if it was beyond being an early-stage startup), and employing at least 50% of its workforce, not including employees on temporary contracts, in the state of Karnataka itself. The exit criteria called out revenue (in the sense of crossing 500 million Indian Rupees), and age (as crossing four years since registration or incorporation). The NASSCOM Zinnov 2018 report classified an Indian startup as having been incorporated in 2013 or later, having founders of Indian origin, with product development being carried out primarily in India. The startup was required to at least have a prototype or minimum viable product (MVP) in place. In this manner, the criteria reinforced the distinct social markers for the actors, in the sense of nationality and catchment area for constituting the workforce, as well as other dimensions of time, such as the years since incorporation or registration and stage of development and funding, and space, through the need for the startup to have been incorporated or having its value adding functions within a geographical boundary. With each subsequent stage of scaling-up, the necessary evidence was acquired as at once a qualification and an exercise in preparing for the forthcoming stage. As the entrepreneur-founder of an established communications startup we interviewed explained, what ‘every incubator, investor or founders’ collective’ will expect is for the founder to ‘plan for growing the business step by step, market by market, product by product’ and in the process, ‘think ahead for and anticipate the team, the service and product offerings, and the market plans you need for the next phase’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). In other words, the dominant, conventional practice of entrepreneurial scale can then be analysed, as at once ‘the product of a dialectical relationship between a situation and a habitus’ (Bourdieu 1977 [1972], 261), where entrepreneurs’ cultural, social, and symbolic capital in the form of community and professional networks reinforces the inference that scale begets scale.

Our study also suggests that the startup ecosystem has begun to drive a level of consistency in its language, with actors across the spectrum presenting their asks for funding, pitches, and success stories within the conceptual categories of age, company stage, funds already raised, education, prior startup experience, and awards as evidence of external validation. In this Goffmanesque presentation of the entrepreneurial self, scale has found another ontological materialization in the shape of hashtags such as #30under30 and #40under40.

Possibilities beyond the dominant discourse

Within the extant narratives, the ability to effectively jump ahead, through space and time, is also celebrated. In 2018, a relatively unknown B2B marketplace progressed to Series C funding of USD 225 million within a record 26 months. Similarly, the transnational discourses of global ambitions were underlined, being defined in terms of expansion to markets outside India, entry of global startups in India, as well as the formalization of international startup exchange missions to promote global flows of capital, products, and entrepreneurs. Scale evolved to be expressed as not only higher, but also faster and wider. In 2019, one-fifth of the startups in India were focusing on global markets. At the same time, national projects such as AADHAR (providing a 12-digit unique identity number to Indian residents or passport holders, based on their biometric and demographic data) fuelled the digital infrastructure and materialization of data in the form of India Stack. The target addressable market in India was accelerating as well and, in 2019, 47% startups were reported to be serving low and middle income groups (NASSCOM Zinnov 2019). This construct of leapfrogging was extended to the agendas of development as well, in the manner of social impact and scale going hand in hand. Social impact incubators and accelerators for example, now evaluate startups applying for their programmes, on the strength of being able to demonstrate scalability across the country as well as evidence a customer base as a display of commitment to the solution.

In other words, and as we have shown here, even the dominant and conventional notions of scale were beginning to demonstrate multidimensionalities. In turn, this points at questions in conflation with InnoCubator’s quest to identify alternate models of value that could help support its incubatees in their journey of scaling, asking whether scale always moved in the same direction. Does scale, with its multidimensional ontology, always progress up the continuum? Could there not be an opportunity to maintain or augment impact while operating at the lower end of continuum, at a given scale? Could this suggest an alternative model of realising value? Was the focus to enable startups to scale up, creating a vacuum at the lower end of the scale? Were there entrepreneurs who were already surviving and even thriving in this space? Could the project of scaling up continue without tethering value at the lower points of the scale continuum? These are the questions we now turn to.

TETHERING AT DIFFERENT POINTS OF THE SCALAR CONTINUUM AS AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP

‘When I joined about two and half years ago, I was the first employee,’ said Aravind, the marketing lead at Diverstics. ‘Today we have twelve staff members, an extended team of over two hundred and fifty women who we call our Language Experts, and nearly 1.5 million downloads and installations of our app. Yet we continue to remain true to our vision of using technology to help people learn vernacular languages for everyday use.’ ‘The women, our Language Experts… they are very dear to us,’ added Arpita, the founder-entrepreneur. ‘We have not met even half of them in person, what with some living in villages and towns as far away as the eastern states of Bengal and Odisha. They are the ones who help in both creating and validating vernacular content on the platform, and that is a key part of our value proposition, in the sense that content is easy to follow and, if I can dare say so, colloquial. I mean at the end of the day, Diverstics is all about the spoken language, the everyday language. So what these women do, essentially comprises our core competitive advantage. But what we truly treasure is the value which we have been able to create for these women. By providing them with incomes, we have enabled financial independence, and thereby, secured empowerment. As a woman and as a human being, that is very important to me.’ ‘This deep respect and empathy for different members of our ecosystem, not just our app users, is intrinsic to our culture,’ asserted Aravind. ‘And we have sustained it by separating out the low-effort, continuous revenue generating business of language translation services. That keeps the engine running, and our investors are okay with our financials.’ ‘At the same time, we are working on stabilizing our technology platform, so that we can leverage the first mover advantage we currently enjoy in this space,’ qualified Kiran, Diverstics’ technology lead. ‘After all, we need to be prepared for a time when others jump in. Even if the likes of Reliance Jio or Google were to make an entry, our technology, data, and the service and quality levels they can deliver, should be able to compete against their scale.’

Diverstics’ office in South Bangalore was spartan. The decor was almost brutal, the furniture and equipment but utilitarian. Yet from the appreciative clapping all around the meeting room at Kiran’s words, it was evident that the antiseptic and functional materiality of the office was not mirrored by the clearly enthusiastic and closely knit team. We could not help but ask as to what they believed was needed to be done in preparation for eventual competition. ‘We need to stay on top of the right set of performance metrics,’ Arpita answered confidently. ‘The number of installed cases, our monthly active users, user retention rates, and revenues from the B2C product and B2B services businesses taken separately are some of the measures we track at the moment. We need to be certain of what we are doing, and when we do it. I mean, we need to grow for sure, but we cannot lose our grip on the business we have built, or the culture which we have so painstakingly nurtured. There will always be the next opportunity. And we can be big. But we cannot afford to grow too fast. Everyone does not have to be a Jack Ma, Mark Zuckerberg, or Jeff Bezos. We need to be extremely careful and focused on who we bring on board, whether investor, staff, or extended team.’ (Field Notes Extract 2019)

Diverstics’ case proffers itself as an exemplar of effectuation (Sarasvathy 2001) in the sense of the entrepreneur not operating solely under the boundaries of the intended effects of scale, such as expansion and grabbing market share, but instead creating the market as a potentiality of existing means, that is, ‘through a network of partnerships and precommitments’ (Burt, quoted in Sarasvathy 2001, 254). Thus, impact in the sense of women empowerment is consciously arranged alongside investor-friendly metrics such as revenue, users, and new markets, in an inter-scalar reinforcement of what could be its area of focus, given the stage it is in. Diverstics’ focus on technology which is at once accommodative of expansion as also a catalysing of a stable business model, is anchored in Philips’ situated assertion of ‘a totalizing coherence of the overlapping scalar dimensions, a mutual propping up of each other’ (Carr and Lempert 2016, 14).

Thus, Diverstics represents but a small, albeit growing, breed of entrepreneurs in India who are seeking to redefine startup scale in the inter-scalar sense of being both multidimensional as well as temporally situated. In this sense, they contest the dominant narratives of a unidirectional trajectory with future imaginaries where, as we have explained before, scale begets scale. Instead, they choose to lay anchor in and explore the potentialities which their temporal-space-present offers: they choose to be tethered.

Perhaps our own example demonstrates this better. In 2018, we co-founded a design research firm which sought to bring ethnography as a praxis to the field of management consulting. Our earliest projects were largely won on the strength of our professional networks. Thereafter however, as word of our work spread, we were able to establish a run rate of a project every month, sometimes more. By the time we were a fifteen-month old organization we had scaled up in every sense, with eighteen projects across India, the Middle East, and Scandinavia, as well as having gone from four founders to a team of ten staff members. Yet that is precisely when we felt it was necessary to consolidate. We invested in specific training for the team, doubled down on establishing a distinctive, and researched client methodology. That was also the time that the two of us took time to pursue a second degree, this time in social anthropology, to add academic teeth to our offerings. In this way, we consciously chose to remain tethered, at the point of scale which we were.

In her paper titled Meaningful Innovation: Ethnographic Potential in the Startup and Venture Capital Spheres, Haines (2016, 175) posits that ‘diffusion’ or scale tends to constrain the potential of the technology startup ecosystem to contribute to ‘more powerful innovations’, since ‘truly disruptive innovations … by definition take time to diffuse’. She highlights how funding is precluded by evidence of scale, as she advances:

The focus, rather, is on evaluating whether the product will scale before actually fully developing it. The process moves from finding potential early-adopter customers for an idea, to refining that idea based on how they may use the product, to then developing the actual product. The potential for diffusion precedes the innovation. (Haines 2016, 178)

Haines’ powerful pronouncements are mirrored in our field observations. There is the founder of a grassroots organization which has been working to gainfully channel corporate social responsibility funds across South Asia, who tables that ‘everything needs to run its its own due course’ as he narrates how it took almost fifteen years from the time that he had first spoken with its chairperson, for his firm to start working with a regional enablement organisation, as ‘scale and replicability, which go hand-in-hand, take time’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). Equally remarkable are the founder-directors of a big data analytics company which has been bootstrapping since 2012 even as it has grown to operations in India and Singapore, who voice their belief in staying rooted in the core offering they are bringing to the market, instead of pursuing the ‘glamour of wider markets, whether customers, geographies or product lines’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). And finally, there is the affirmation by the now-profitable augmented reality start-up who says that, given an opportunity, he would go back in time to not raise the investments he then had, as he laments that while they certainly benefited from the money having come in, the ‘10x problems also led to 10x problems’ as the ‘fundamental drive of the investor is to scale, and find a buyer notwithstanding the actual work’ (Field Notes Extract 2019).

In short, our research confirms that notwithstanding the more dominant narratives and discourses outlining scale as ‘taking wings’ or ‘achieving escape velocity’ (Startup India 2020), often aligning themselves with a ‘mechanism of panopticism’ (Foucault 1991, 216) which investors privilege by focusing on scale as a reflection on the entrepreneur’s performance and capabilities, startups are increasingly beginning to explore potentialities and innovation at the existing point of the scalar continuum they find themselves on, through an exercise in consolidation and tethering. Furthermore, and running counter to popular perception, tethering as a means of seeking an alternative approach to value, is emerging in entrepreneurship across sectors and models, both those which are for-profit as also those categorised as social enterprise.

What this does ask then, is as to what tethering at different points of the scalar continuum could offer, as an alternative model of entrepreneurship for the startup ecosystem. A possible answer is the opportunity for building relativity of scale. There is for example, the case of an established for-profit enterprise, which equips each of its clients, an overwhelming majority of which are for-profit sole proprietorships or limited liability partnerships, with the wherewithal to realise a steady earning potential grounded in the socio-economic mise en scène to which its founders, staff, and customers belong. Yet as our research indicated, it is not just the startup enterprises themselves, but even the institutional mechanisms and frameworks which are beginning to not just support but also facilitate such alternative models of value. Thus, alongside its efforts to set up incubation centres with a view to helping innovative startups become ‘scalable and sustainable enterprises’, the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM) as the Government of India’s initiative to ‘promote a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship in the country’ has also begun to set up Atal Community Innovation Centres (ACICs) to ‘focus on underserved/ unserved regions’, it finalises plans to launch Atal Research and Innovation for Small Enterprises (ARISE). In fact, ACICs are part of a growing breed of incubators which are looking at incubating startups from low-income towns and districts which are solving for the underserved and underprivileged.

In drawing this chapter to a close, we offer a final ethnographic example of such scalar relativity. As part of our project, we carried out an ideation exercise for and with the founders of Chalk Test. Participating in the process were the startups portfolio managers from the incubator-investor InnoCubator, two of the startup’s industry mentors, as well as members of a research team from InnoCubor which provided technical assistance to startups. For an exercise which started with the problem statement of scalar connotations, reading as ‘how might we clarify our value proposition(s) for different users so as to have a commercially viable offering’, it was remarkable that the principal areas of action were identified around positioning the app for only one set of stakeholders instead of all categories of users on one hand, and also working on strengthening but two identified internal processes (Field Notes Extract 2019). And what made this incident all the more noteworthy was the additional investment by InnoCubator in Chalk Test, which followed a few months thereafter, on the strength of what was effectively an exercise in tethering or consolidation, at the point which the startup was. Thus in tethering, it is not just that there are rising instances of scale’s traditional, even hegemonic narrative, being resisted. Rather, and perhaps more significantly, the discourse is increasingly being negotiated in the form of its hitherto nonscalable articulations, to borrow from Tsing (2016), targeting scale at that point. Scale which is at once, tethered.

TOWARDS AN ONTOLOGY OF DESIRE, AS A WAY IN AND WAY OUT

‘Duniya badalne ke sab ke apne-apne tarikey hai (Everyone changes the world in different ways)’ – from the Netflix movie Upstarts (Pawar 2019).

We explored an ethnography of mass media to reflect on how the imagined community of startups in Bangalore is depicted and consumed by audiences. The movie Upstarts, released on the OTT media service Netflix in 2019, was touted by its director, Udai Singh Pawar, as the answer to yet another transnational discourse. ‘Why is there no Indian equivalent to international film ‘‘The Social Network’’?’ (Outlook India 2019). Diffusion or scale does indeed take the shape of myriad concomitant flows.

Pawar drew upon his own lived experiences and interactions to advance an emic perspective, ‘I studied at IIT Kanpur, and worked at Microsoft Research for three years. I have a background in Bengaluru because I lived there’ (Outlook India 2019). The feature film follows three young men, from ‘small town India’, in yet another reiteration of the startup founder archetype. Tragedy begets resolve, as they are inspired to help provide the underserved with access to medicines. They design a technology led logistics solution which is essentially an app, register their own company, and start pitching their idea to funders as the natural next step. An inability to portray a clear value proposition leads to many failed pitches, before a chance encounter with an angel investor at an airport turns fortuitous. Money flows in, and then seamlessly, scale becomes a reality. The film plays on familiar tropes and establishes binaries as points of conflict: impact versus scale, founders versus investors, male privilege versus women entrepreneurs, and even interrogations such as ‘what has greater value, their dreams or their friendship?’ (Outlook India 2019). Interestingly, any desire to do something different is shown to exist outside of the project of funding and successful scaling. Two co-founders having an ideological conflict with the investor opt out after a certain progression of scale, as a result of dissonance with their desire for creating ‘values that make for positive change’ (Haines 2016, 197). The remaining co-founder then assumes the mantle of CEO, is hand-held by the investor and further progresses along the continuum. In this manner and form, the anchoring values are relegated to the background, and eventually abandoned at the behest of the funders. It makes an insignificant ontological appearance as a small team inconspicuously alluded to as the NGO department, that is clearly demarcated from the rest of the firm, in terms of space (separate workspace) and time (not keeping pace with the growth). A woman entrepreneur, who is a friend of the principal protagonist (the founder-CEO who continues with the firm and the investors), struggles to get funding (and screen time) for her own endeavour of ‘creating a mental health support system’, since it is not viewed as being investment-friendly. In addition, this venture is even positioned as non-tech with the women entrepreneur shown as personally engaging with an individual to save him from taking his own life. Finally, the founder-CEO is dismissed by the board for non performance, and utilises the opportunity to anchor back to his desires, reestablishes communitas with his two estranged co-founders, and is reintegrated with his values as he goes to working with his NGO team in a village on real issues. The social drama is resolved only when scale is sacrificed for values and societal impact. In a media interview, the director, Pawar asserted that ‘…the film is realistic and authentic, and based on hundreds of true stories’ (Outlook India 2019). This claim entrenches the popular understanding of the startup ecosystem in Bangalore.

In this manner, we see that the film outlines desire as a way out of the structure of scale, and never as an instrument of negotiation. This notion finds resonance in Haines’ research as well. Taking the example of an erstwhile startup, Obatech, in Indonesia, Haines outlines how Venture Capitalists, privileging short term returns over long term vision, force ‘a distinctive shift in values—a shift that moves teams from doing something potentially meaningful and of value for a particular type of end user to doing something that potentially leads to value for the VC firm’ (Haines 2016, 195). She builds the case for research in the ecosystem to examine emerging ‘domains of interest’ and ‘to explore such contexts and routines and identify areas of opportunity … as areas for positive disruption’ (Haines 2016, 192). She puts forth compelling evidence for the relevance of anthropological theories and ethnographic approaches, in the manner of enabling a better framing, understanding, and assessment of teams and funding decisions (by the Venture Capitalists) as well as embedding value in the innovation process.

Our research however points us to another set of realities or multiplicities. We borrow an epistemological concept from Ravi Sundaram’s study of pirate culture in Delhi (2010) to explore this. Can the entrepreneurial desire for value be analysed as the ‘contagion of the [un]ordinary’ (Sundaram 2010, 15) that does not resist the discourses of power, but revels in its cracks and gaps? Should concomitant streams of nonscalability be viewed as lines of flight which, even while running along the periphery of incumbent structures, always carry the possibility to escape and thus, create potentialities for creativity and disruption? Our research shows that the lines of flight of desire can enter, exit, or run along the continuum of scale at will. Startups, while focused on vision and impact, enter projects of scaling to be able to experiment and pivot. This is aided by the fact that the system is inherently characterized by a high tolerance for failure. ‘Entrepreneurs cum investors, however, tend to have a higher risk tolerance, which in theory helps spur innovation at a much higher rate than corporate R&D’ (Kaplan and Lerner as quoted in Haines 2016, 188). As one Venture Capitalist shared, ‘Sometimes, funding enables that pivoting and subsequent acceleration’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). At the same time, one cannot escape from the focus on conventional performance metrics endorsed by Venture Capitalists including retention, growth, acquisition growth, daily and monthly active users, lifetime value of a user, acquisition cost, profit margin, and potential market size, amongst others (Haines 2016, 193). While managing these metrics as feeds for funders, investors, incubators and accelerators, the founders also retained their focus on sustenance of value. The multiplicity does not end there. As we have mentioned earlier, there were entrepreneurs who chose to remain entirely outside of these structures or ‘bootstrapping’ for ‘keeping our head above water for a long time may be sufficient’ (Field Notes Extract 2019). And then there were others who entered the ecosystem, but exited after realising that untethered growth was unsustainable, ‘we had 10x money and 10x problems, and chose to scale down’ (Field Notes Extract 2019) and chose to assemble again, ‘And that’s when we doubled on efficiency – and it was this reason that we are profitable today… core business logic cannot be done away with’ (Field notes Extract 2019). Our research opened up a future line of enquiry. It was evident that entrepreneurs have started finding meaning in alternative modes of value, which can even exist alongside projects of scale. It would be interesting to see if and how these desires as lines of flight in turn facilitate a Deleuzian becoming of the startup ecosystem. This presents another opportunity for ethnographic research as a method to study emergent trends in the reterritorialization of the startup ecosystem.

CONCLUSION

In a world at once digitally connected and dispersed, Horst (2012, 72) reminds us of the need to remain committed to the ‘classic anthropological ways of knowing’, including but not limited to an ‘attention to change over time’. The suggestion’s singular message exhorts us to keep on returning to the field, an act rendered all that more germane for us, being as we are both ethnographers and entrepreneurs. And we have faithfully returned since the time of our research in 2019, to note developments in keeping with our observations, which confirm our ethnographic readings. Scale as facilitated by language, for example, is beginning to be challenged through incubators which are now looking to provide entrepreneurial support and guidance in the vernacular, not just in English. Their argument is built on the view that a restricting of communication, incubation support, and mentorship to the English language alone, is an effective limiting of the pool of entrepreneurs, not too different from Anderson’s imagined communities premised on a ‘consciousness’ imagined through the ‘unified fields of exchange and communication’ (1991, 44). There are also drives to onboard an increasing number of women entrepreneurs, mentors, and coaches, in an attempt to bridge the gender gap across the continuum, often in conjunction with a focus on a regional startup ecosystem. An example is the ‘Her&Now’ programme being led by the Government of India’s Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MoSDE), along with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, to better the ‘framework conditions for businesses managed by women in India’ in the states of northeastern India, as well as those of Rajasthan and Telangana (GIZ 2020). As an initiative which focuses on historically neglected regions, there is an institutional push for tethering.

In summary, there is no doubt then, that the question of scale is evolving. Dominant discourses of power/knowledge remain, but alternative perspectives have started to emerge alongside, in a decidedly syncretic manner of assemblages. The actors include not only startups themselves, but institutional enablers such as incubators and accelerators, as well as regulatory and administrative machinery. Even more significantly, and situated within this multidimensionality of scale, are projects of scale-making both tethered or at a point, as well as in the form of potentialities of desire comprising alternative ontologies of value. And while our ethnography was situated in India’s startup capital, there is much to learn for stakeholders of startup ecosystems the world over, whether entrepreneurs, funders, incubators, accelerators or governments and regulators. For there is no shame in not scaling. It is no longer construed as failure or a rite of passage for an entrepreneur. Everybody then, is a winner.

Gitika Saksena is a Director at LagomWorks Consulting. LagomWorks is a research and innovation consulting firm, leveraging principles and methods of Design Thinking and Ethnographic Research to drive transformation and innovation. Prior to LagomWorks, she was a Vice President at Accenture Technology in India, where she led the strategy for various talent initiatives. She has just completed her second Masters’ degree in Social Anthropology from SOAS University of London on a British Chevening Scholarship.

Abhishek Mohanty is a Director at LagomWorks Consulting. LagomWorks is a research and innovation consulting firm, leveraging principles and methods of Design Thinking and Ethnographic Research to drive transformation and innovation. Prior to LagomWorks, he was an Associate Director in Management Consulting at PwC India. Abhishek has just completed his second Masters’ degree in Social Anthropology from SOAS University of London on a British Chevening Scholarship.

REFERENCES CITED

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977 [1972]. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Briody, Elizabeth K., and Alex Stewart. 2019. “Entrepreneurship: A Challenging, Fruitful Domain For Ethnography”. Journal Of Business Anthropology 8 (2): 141-166. doi:10.22439/jba.v8i2.5846.

Carr, E. Summerson, and Michael Lempert, eds. 2016. Scale: Discourse and Dimensions of Social Life. Oakland: University of California Press.

Chitnis, Shailesh. 2018. “The Secret Sauce Behind A Successful Indian Start-Up”. Mint, January 11. Accessed May 8, 2020. https://www.livemint.com/Companies /gIzjSNuBykoPFmPIVopk5J/The-secret-sauce-behind-a-successful-Indian-startup.html.

Desjarlais, Robert, and C. Jason Throop. 2011. “Phenomenological Approaches In Anthropology”. Annual Review Of Anthropology 40 (1): 87-102. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092010-153345.

EPIC. 2020. “Theme.” Accessed May 31. https://2020.epicpeople.org/theme/.

Foucault, Michel. 1991. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (translated by Alan Sheridan). New York: Vintage Books.

GIZ. 2020. “Empowering women to become entrepreneurs.” Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/75649.html.

Goffman, Erving. 1971. The presentation of self in everyday life. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Haines, Julia Katherine. 2016. “Meaningful Innovation: Ethnographic Potential in the Startup and Venture Capital Sphere.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2016: 175-200. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.epicpeople.org/meaningful-innovation/.

Horst, Heather A. 2012. “New Media Technologies in Everyday Life.” In Digital Anthropology, edited by Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller, 61-79. New York: Berg.

Knowledge@Wharton. 2019. “Three Waves: Tracking the Evolution of India’s Startups.” Accessed July 30, 2020. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/three-waves-tracking-evolution-indias-startups/.

Mansfield, Nick. 2000. Subjectivity: Theories of the Self from Freud to Haraway. New York: New York University Press.

NASSCOM Zinnov. 2018. Indian Tech Start-Up Ecosystem: Approaching Escape Velocity. Noida: NASSCOM India.

NASSCOM Zinnov. 2019. Indian Tech Start-Up Ecosystem – Leading Tech in the 20s. Noida: NASSCOM India.

Outlook India. 2019. “Upstarts: The Story Behind India’s First Film On Startups.” Outlook, October 17. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/upstarts-the-story-behind-indias-first-film-on-startups/1642485.

Pawar, Udai Singh, dir. Upstarts. Bandra West Pictures, 2019. https://www.netflix.com/title/80998890.

Philips, Susan. 2016. “Balancing the Scales of Justice in Tonga.” In Scale: Discourse and Dimensions of Social Life, edited by E. Summerson Carr and Michael Lempert, 112-132. Oakland: University of California Press.

Samudra, Jaida Kim. 2008. “Memory in our body: Thick participation and the translation of kinesthetic experience.” American Ethnologist 35 (4): 665-681.

Sarasvathy, Saras. 2001. “Causation and effectuation: towards a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency.” Academy of Management Review 26 (2): 243-288.

Sarukkai, Sundar. 1997. “The ‘Other’ in Anthropology and Philosophy.” Economic and Political Weekly 32 (24): 1406-1409.

Sayes, Edwin. 2013. “Actor–Network Theory And Methodology: Just What Does It Mean To Say That Nonhumans Have Agency?” Social Studies Of Science 44 (1): 134-149. doi:10.1177/0306312713511867.

Sengupta, Vishnupriya and Suvarchala Narayanan. 2019. “India’s New Unicorns: The world’s largest democracy is becoming a seedbed for billion-dollar startups.” strategy+business, October 21. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.strategy-business.com/feature/Indias-new-unicorns?gko=76038.

Sharma, Neetu Chandra. 2020. “Why women entrepreneurs are missing from India’s startup story.” Mint, February 21. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.livemint.com/companies/start-ups/

why-women-entrepreneurs-are-missing-from-india-s-startup-story-11582267821850.html.

Spradley, James. 1979. The Ethnographic Interview. Fort Worth, Tex.; London: Harcourt College Publishers.

Startup India. 2020. “Karnataka Startup Policy 2015-2020.” startupindia.gov.in. Accessed July 29, 2020. https://www.startupindia.gov.in/content/dam/invest-india/Templates/public/state_startup_policies/Karnataka_Startup_Policy.pdf.

Sundaram, Ravi. 2010. Pirate Modernity: Delhi’s Media Urbanism. Oxford, New York: Routledge.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2019. “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales.” Common Knowledge 25 (1-3): 143-162.

Variyar, Mugdha. 2018. “Seed Stage Funding Falls 20%, Late Stage Funding Grows 259%: Nasscom Startup Report.” The Economic Times. October 25. Accessed July 29, 2020. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/seed-stage-funding-falls-20-late-stage-funding-grows-259-nasscom-startup-report/articleshow/66361259.cms.