This is a cautionary tale featuring a well-structured memo and an effective, carefully designed infographic. Both of these artifacts could be considered excellent examples of their respective crafts—the first of technical communication, and the second of graphical information design. Both are also examples of how ethics can be subsumed to expedience, and how the everyday practices of their production were subject to the exigencies of locally acceptable rhetorics and social order.

I believe the stories of these artifacts are cautionary tales for us and our own work. Through the (admittedly dark) cautionary tales of these artifacts, I invite us to consider the conditions in which we, EPIC attendees and our international community, produce artifacts that convey “evidence”. I invite us to question the milieux and “atmospheres” in which we work, the sources from which we collect data, our practices and processes when producing evidencing rhetorics, and the role of such evidence in design decision making.

The Memo

Below is an extract from a memo showing one of three recommendations created by a German bureaucrat, Just, for his boss in June 1942. In the memo, Just argues for some changes to a number of service vehicles and service operations with supporting evidence for his recommendations (the whole memo is reproduced at the end of this blog post).

Geheime Reichssache (Secret Reich Business) Berlin, June 5, 1942

Changes for special vehicles now in service at Kulmhof (Chelmno) and for those now being built

Since December 1941, ninety-seven thousand have been processed by the three vehicles in service, with no major incidents. In the light of observations made so far, however, the following technical changes are needed:

1. The vans’ normal load is usually nine per square yard. In Saurer vehicles, which are very spacious, maximum use of space is impossible, not because of any possible overload, but because loading to full capacity would affect the vehicle’s stability. So reduction of the load space seems necessary. It must absolutely be reduced by a yard, instead of trying to solve the problem, as hitherto, by reducing the number of pieces loaded. Besides, this extends the operating time, as the empty void must also be filled with carbon monoxide. On the other hand, if the load space is reduced, and the vehicle is packed solid, the operating time can be considerably shortened. The manufacturers told us during a discussion that reducing the size of the van’s rear would throw it badly off balance. The front axle, they claim, would be overloaded. In fact, the balance is automatically restored, because the merchandise aboard displays during the operation a natural tendency to rush to the rear doors, and is mainly found lying there at the end of the operation. So the front axle is not overloaded.

2. …

Objectivity is a requirement of technical writing as a genre, and this memo satisfies that criterion. The author presents clear, concise recommendations based in evidence. Two things are of further note: (1) no definitions are offered for “load” nor for “pieces”, implying a pre-existing, shared understanding between author and reader(s), and (2) there is at no point any questioning of the rightness or wrongness of the memo’s intent nor of the “service” in question. In its production, the writer of the document didn’t question the need for the memo, nor the ethics of the content; he merely functioned as a bureaucrat, fulfilling his duty.

We know now of course, that with the word the “load” the author is referring to those targeted for transportation to the concentration camps, including anyone Jewish or of Jewish descent, LGBTQ individuals, the physically and mentally disabled, and Roma (also known as gypsies). The detachment and cold logic of the memo is, to us, truly chilling. The fact that the words, the intent, and the program within which this memo operated and circulated were never defined, nor questioned, is shocking.

Expedience is about getting what needs to be done…done. It is about taking advantage of opportunities now and efficiently executing on the next task to be done, without regard for the consequences. Expedience is a regard for what is politic or advantageous rather than for what is right or just. Expedience is lean, and satisfies a specific self-interest. In his analysis of this memo in his paper, The Ethic of Expediency: Classical Rhetoric, Technology, and the Holocaust, scholar Steven Katz argues that the expediency of this memo had its own local, ethical logic—Katz calls it “the ethic of expediency”. Reminiscent of Aristotle’s “utility is a good thing”, the ethics of expediency put the functionality of the document above its content, and above the broader ethical concerns of the intent and the context of its content.

That broader context was, of course, Hitler’s Nazi Germany. Hitler was a masterful propagandist, using rhetoric as an instrument in the creation of Nazi culture which demanded alignment between the people and the (his) authorities, and the promotion of an ethos of technological rationality, detachment and power. This, coupled with a “group think” of expediency, lay the groundwork for a world in which technological values subsumed politics, ideology, and humanitarian concerns. The memo, in that context, was clear, understandable, effective, and efficient.

Why does this matter?

As per this memo, technical communications—which could include the presentations, the papers, and the blog posts we write—are never objective. They always sit within a context of production and interpretation, and those contexts should be subject to ethical analysis. Katz shows us that there is always a relationship between rhetoric and ethics. In the case of the memo, Katz states: “To understand the holocaust from a rhetorical point of view is to understand the extreme limits and inherent dangers of the prevailing ethic of expediency as ideology in a highly scientific and technological society, and how deliberative rhetoric can be subverted and made to serve it”.

Writing a technical memo is an ethical act. And being objective as a technical writer should not equal being devoid of any humanitarian evaluation while creating the document. Technical writing needs to be based “on deliberative rhetoric from the standpoint of both rhetoric and ethics” [the italicised emphasis is mine].

The Infographic

Mark Ward’s follow-up article, The ethic of exigence: Information design, postmodern ethics, and the Holocaust, addresses the power of infographics, extending Katz’s analysis beyond expedience and into exigence.

Exigence is the pressing situation in which we act. It refers to the need, demand, or requirement that is intrinsic to a circumstance. It is worth distinguishing between rhetorical and non-rhetorical exigence. Stephen Croucher in his book Understanding Communication Theory: A Beginner’s Guide offers an example to illustrate the difference:

“A hurricane is an example of a non-rhetorical exigence. Regardless of how hard we try, no amount of rhetoric or human effort can prevent or alter the path of a hurricane (at least with today’s technology).

However, the aftermath of a hurricane pushes us in the direction of a rhetorical exigence. We would be dealing with a rhetorical exigence if we were trying to determine how best to respond to people who had lost their homes in a hurricane. The situation can be addressed with rhetoric and can be resolved through human action.”

Exigence is need shaped by circumstances, and rhetorical exigence allows us to make sense of the circumstance and convey “reasonableness” of any decision that is made about (re)actions in that context. Rhetorical exigence is located in the social world. Carolyn Miller describes it thus: it is “a form of social knowledge, and entails a mutual construing of objects, events, interest, and purposes that not only links them but makes them what they are: an objectified social need”.

Rhetorical exigence can reflect as well as create “group think”. Richard Vatz in his book “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation” argues that when communicators choose particular slants, particular issues, or specific events to foreground, they create ‘presence’ or ‘salience’—it is the choice to focus on the situation that creates the exigence. He offers an example of a president who chooses to focus on health care or military action; this president has constructed the exigence toward which the rhetoric is addressed.

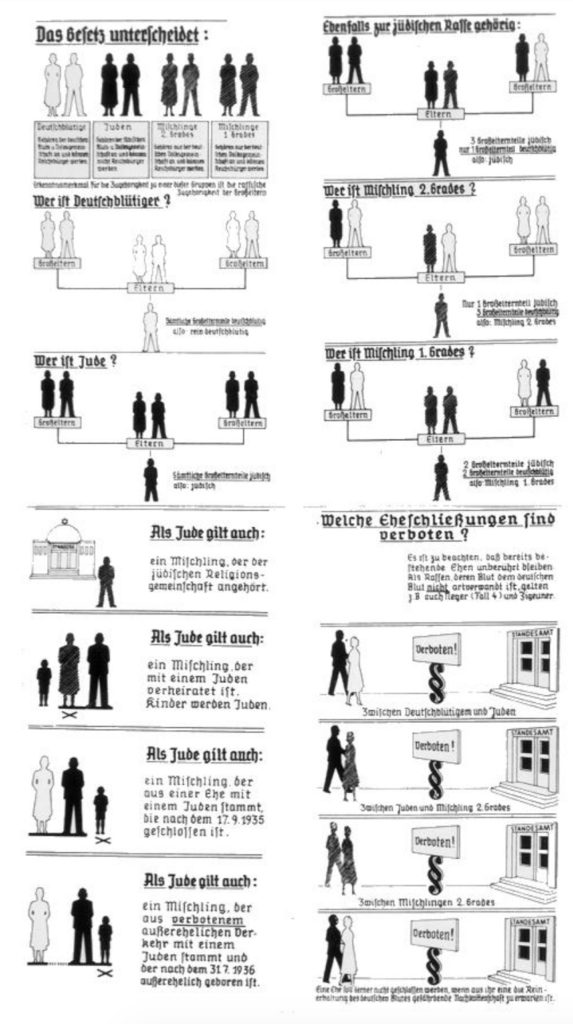

The infographic in question is a 1935 Nuremberg Laws racial-education poster published in Germany.1 The poster graphically categorized people as German-blooded or Jewish, and depicted who could and who could not marry.

This poster is a highly competent example of information design, presenting information clearly and effectively. It is very ‘readable’ and ‘efficient’ in conveying the information at a glance. The poster excelled at rational instrumentality. Its production was also devoid of any ethical analysis in the moment of its production. Nevertheless, it was a highly instrumental artifact within the context of a culture of notionally “scientific”, eugenics-based decisions around categorization, discrimination, mistreatment, and murder of people.

In Ward’s analysis, this poster was exigent; there was a need to respond to the complexity of the Nuremberg Laws, which were difficult to read and understand in their textual form. The rhetorical exigency in this poster is manifest in the specifics of the presentation. The infographic rendered the content within the laws accessible at a glance—just as a good infographic should do. The ‘‘ethic of exigence’’ (Ward’s term) here though, is the way the information designers who produced this poster operated within a system of “need” (to make clear what was within the laws), and their engagement in the design of the poster. Ward states: “Information design is given seemingly rational meaning only through the agreement of the designer and user to co-construct this meaning, a process by which persons collaborate in an attempt to bring their version of what is necessary, noble, and good and to preclude the enactment of what they fear, hate, or despise”. “Information design must arrange text and graphics to have symbolic influence for given cultures” he says, and within the eugenics-based culture of Nazi Germany, the poster was immensely effective, efficient, and it was also “exigent”.

This excellent example of infographics was produced without any consideration of the ethics of acts that would be enabled by its existence, and without any humanitarian consideration.

Evidence, Data, Rhetoric, and Reasoning

These are grim examples and I am making points we likely all agree upon.

What do they have to do with our daily work, or the papers and presentations we create for EPIC2018, or the conversations we have and community that evolves there? Because we need to remember that less grim, critically important examples of evidencing without ethical2 reflection are happening all the time. I am inviting us to hold the example of the memo and the infographic in mind, and to consider the central role of rhetoric and representation in evidencing. If evidencing underlies decision making, we must demand careful reflection about the choices that are made in our evidencing rhetorics. We must elevate practices that look out for data distortion and absence of evidence. We must spend time imagining potential unintended consequences before those negative unintended consequences come to pass.

We must also acknowledge that the exigencies of our work lives may take us in directions where unethical actions may be enabled. In our world, “economic expediency” drives much behavior; we must keep remembering that this expediency is both political and ideological. Businesses operate in their own self-interest, a self-interest that is narrowly defined by a market that sets the non-negotiable metrics for success and the non-negotiable time frame for evaluation. Companies that don’t operate in this way are unusual, and use their focus on the greater good, rather than expedient self-interest, as positive marketing.

Further, many of us operate in contexts that laud speed of innovation and technological “progress”. Langdon Winner, another scholar and commentator on technology and society, calls this the “technological imperative”, the idea that technologies are inevitable and essential, and that they must be developed and accepted for the good of society. Sometimes, technologies are developed just because they can be. Following Ellul, Winner says come to exist only because they are the next logical step along a path to which we are already committed. Under such conditions, our cultural orientation toward “innovation” in technology design and development can become one of “pervasive ignorance and refusal to know.”

I’d also like us to turn our collective critical eyes toward our own work practices, our own filters, and our own bubbles. I am heartened that a greater focus is emerging on the ethics of technology design and development. The ACM recently came out with a refreshed Code of Ethics, the first revision in 26 years; within it are numerous calls to computing professionals to take an active stance when it comes to reflecting on the work they are doing. In a similar vein, I was recently given a copy of IDEO’s Little Book of Design Research Ethics, which contains many practical steps to conducting ethically grounded design research.

More explicitly, I want us to consider: Are we consciously and publicly reflecting on what we want technology for? Are we, in any way, looking too narrowly, confined by the exigencies of our settings? Are we reflecting on the breadth and the depth of evidence? Are we questioning not just deep enough, but also broadly enough into the past and into the future? How are we generating artifacts that show evidence? What are our processes, rhetorics, and representations of evidence and our practices of evidencing?

We need to do this reflection together, and we need to take a long distance view. And that is why “getting out of the office” and coming to EPIC was, for all of us who are attending, a great decision!

The Memo in Full

Geheime Reichssache (Secret Reich Business) Berlin, June 5, 1942

Changes for special vehicles now in service at Kulmhof (Chelmno) and for those now being built

Since December 1941, ninety-seven thousand have been processed [verarbeitet in German] by the three vehicles in service, with no major incidents. In the light of observations made so far, however, the following technical changes are needed:

[1.] The vans’ normal load is usually nine per square yard. In Saurer vehicles, which are very spacious, maximum use of space is impossible, not because of any possible overload, but because loading to full capacity would affect the vehicle’s stability. So reduction of the load space seems necessary. It must absolutely be reduced by a yard, instead of trying to solve the problem, as hitherto, by reducing the number of pieces loaded. Besides, this extends the operating time, as the empty void must also be filled with carbon monoxide. On the other hand, if the load space is reduced, and the vehicle is packed solid, the operating time can be considerably shortened. The manufacturers told us during a discussion that reducing the size of the van’s rear would throw it badly off balance. The front axle, they claim, would be overloaded. In fact, the balance is automatically restored, because the merchandise aboard displays during the operation a natural tendency to rush to the rear doors, and is mainly found lying there at the end of the operation. So the front axle is not overloaded.

[2.] The lighting must be better protected than now. The lamps must be enclosed in a steel grid to prevent their being damaged. Lights could be eliminated, since they apparently are never used. However, it has been observed that when the doors are shut, the load always presses hard against them as soon as darkness sets in. This is because the load naturally rushes toward the light when darkness sets in, which makes closing the doors difficult. Also, because of the alarming nature of darkness, screaming always occurs when the doors are closed. It would therefore be useful to light the lamp before and during the first moments of the operation.

[3.] For easy cleaning of the vehicle, there must be a sealed drain in the middle of the floor. The drainage hole’s cover, eight to twelve inches in diameter, would be equipped with a slanting trap, so that fluid liquids can drain off during the operation. During cleaning, the drain can be used to evacuate large pieces of dirt. The aforementioned technical changes are to be made to vehicles in service only when they come in for repairs. As for the ten vehicles ordered from Saurer, they must be equipped with all innovations and changes shown by use and experience to be necessary.

Submitted for decision to Gruppenleiter II D, SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Walter Rauff.

References

ACM Code of Ethics, https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics, accessed 09-16-2018

Croucher, Stephen (2015) Understanding Communication Theory: A Beginner’s Guide. Routledge, 2015

Ellul, Jacques (1964) The Technological Society. Trans. John Wilkinson. New York: Knopf.

Katz, S. B. (2004) The Ethic of Expediency: Classical Rhetoric, Technology, and the Holocaust. In J. Johnson-Eilola & S. A. Selber (Eds.), Central works in technical communication (pp. 195-210). New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller, Carolyn (1994) Genre as Social Action. In the New Rhetoric, ed. by Aviva Freedman and Peter Medway. Taylor & Francis, 1994

Moeller, Marie (2015). The obese body as interface: fat studies, medical data, and infographics. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual International Conference on the Design of Communication (SIGDOC ’15). ACM, New York, NY, USA, Article 31, 7 pages. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2775441.2775469

Ward Sr, Mark. (2010) The ethic of exigence: Information design, postmodern ethics, and the Holocaust. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 24.1 (2010): 60–90.

Winner, Langdon. (1977) Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-Control as a Theme in Political Thought, M.I.T. Press.

Notes

1. Instructional Chart. United States Holocaust Museum and Memorial online exhibition, special focus, Nuremberg Race Laws: Defining the Nation, https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/nuremberg-race-laws-defining-the-nation/documents/instructional-chart. Accessed 26 September 2018.

2. Ethics is the branch of philosophy that addresses the rightness and wrongness of certain actions, and the goodness and badness of the motives and results of such actions. Ethics requires out-of-this-moment thinking.

Related Resources

Automating Inequality, Virginia Eubanks

Empathy as Faux Ethics, Thomas Wendt

Radicals in Cubicles, Anne McClard

Ethics in Business Anthropology, Laura Hammershøy & Thomas Ulrik Madsen

0 Comments