Agile methodologies have taken hold as a model to be followed in software industry. Among them, Scrum is one of the most used frameworks and has a high level of acceptance among a large range of organizations. The underlying premise of Scrum is that by implementing an iterative and incremental process of development, an organization can become more efficient in coping with unpredictability, thus, increasing the chances of delivering business value. In this paper we use the context of SIDIA, an R&D center based in Manaus (Brazil), to look at how Scrum is practiced, by following Post-its notes, which are commonly used in agile landscapes.

Following previous work on the idea of thinking through things (instead of thinking about things) as an analytic method to account for the ethnographic experience (Henare, 2006), the purpose here is to draw out the capacity of these objects to re-conceive the workplace. We argue that somehow the extensive use of post-its in this specific context helps to reify the core values of scrum and the agile mindset, at the same time that it shapes much of its practices and discourses.

Although we use a specific context as a case-study to articulate the argument, we are less interested in bringing the specifics of the case, than in throwing light on the current perception of agile methodologies as a site of organizational promise, through an object-oriented approach.

INTRODUCTION

In the last years, agile systems development methods have been widely adopted in many organizations. At the core of this model lays the premise that organizational agility brings value to companies (Pham, 2012; Barton, 2009), understanding agility as a responsiveness to change. Collaborative and incremental software development started around late 1950 but the term Scrum was popularized after an article by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka (1986) in the Harvard Business Review. Here the authors compared and demonstrated the advantage of incremental development over sequential development, that is, between agile and waterfall models of development. Later, in 2009, the first version of the Scrum guidelines was published, in which the roles, ceremonies and terms of Scrum were clearly summarized and defined (Schwaber & Sutherland, 2009).

One key notion in Scrum is agility, although – beyond this generic inclination to change and adaptation – the notion of agility remains ambiguous to a large extent (Iivari, 2011). A precise analysis of the concept is presented by Conboy (2009), who defines it as:

‘‘The readiness of an (agile) method to rapidly or inherently create change, proactively or reactively embrace change, and learn from change while contributing to perceived customer value (economy, quality, and simplicity), through its collective components and relationships with its environment’’ [Conboy, 2009: 340].

As Iivari argues, it follows from this definition that agility is an emergent property of systems in which a certain method is employed. However, it is not conclusive about the techniques and principles through which this is done, and indeed, it leaves room for different approaches as to how to make agility emerge at the level of the whole method (Iivari, 2011). Another well-known source that tackles this notion is the Agile Manifesto (http://agilemanifesto.org/principles.html) which gives a list of features that an agile method should involve, but again, these principles are still very much open to interpretation.

Also, more or less explicitly, the idea of speed lies in agile approaches. Successful agile methods imply not only readiness to change but a rapid and promptly response. In this regard the rhetoric of speed has been extensively appropriated by the field of organizational management, in which time-based strategies are now emphasized as a competitive advantage, and techniques to enhance speed are largely been employed and experimented with among many organizations (Inman, 2010).

In this regard, speed and agility, thus, do not come uncomplicated. A question can be raised about what it is gained and what is missed by adhering to these models. In this work, we problematize the notion of agility, by bringing together a series of ‘vignettes’ that stem from the implementation of Scrum in a specific context. In doing so, we seek to illustrate how the notion of agility is materialized, specifically through the use Post-It notes and, at the same time, how those very things flesh out the specific scope and contours of what agility can be.

THEORETICAL APPROACH

This work draws on different contributions within anthropology which spans actor-network theory, material cultural studies and ontological approaches. The thread opened by Science and Technology Studies (STS), through the so-called “laboratory studies” brought ethnography into the very settings where science is produced through direct observation of the practices and processes along which scientific knowledge is articulated. In this same light, we use ethnography to look at how Scrum is implemented within a particular corporate workplace. To enter our object of study we focus on the materiality of post-it notes, as things that are extensively mobilized throughout the practice of Scrum. By placing these objects at the center of our analysis, we aim to read back from the objects themselves a characterization of the workplace from which such objects emerge. In doing so, we also want to raise a question concerning the rhetoric of speed and movement that usually underlie agile practices.

Anthropology at home

Since the 1970s ethnographic studies were strongly incorporated into STS, an approach that redefined science studies around the notion of social construction (Knorr-Cetina, 1983a), as a means to open the black box of scientific practices. This approach was then enshrined through the work of authors such as Bruno Latour, Michael Lynch or Steve Woolgar by focusing on the social contexts in which scientific praxis happens. For anthropologists, this involved leaving their traditional field sites and entering contexts in which they were no more exogenous observers. A new kind of “anthropology at home” emerged to deal with subjects whose practices were inserted in the same traditions as those of the researcher, thus, problematizing the very premises and practices of ethnographic research (Holmes, D. & Marcus, G., 2008). In a similar move, more recently ethnographers have “entered the corporation” under the idea that anthropology too can influence organizations’ understandings, effectiveness and profits (Cefkin, 2010). Urban & Koh (2012) present a comprehensive background of this phenomenon and contextualizes ethnographic practice within corporations, distinguishing between “in-corporation research” -developed by anthropologists generally based on academia but whose object of study is the corporation- and “for-corporation research”, that is, ethnography by employed anthropologists in companies, usually aiming to produce effects or bring about an improvement within the company.

Things as concepts

Attempts to enter a territory by way of the objects is certainly not new in anthropology. In the field of material cultural studies, the work of Appadurai (1986) was foundational in exploring the multiple ways in which objects are invested with meaning, function and power. Since then, many others have employed different theoretical strategies to argue in favor of the mutually constitutive nature of the relationship between subjects and the objects they create (Ingold 2000; Miller, 1998).

Taking this project a step further, some authors have begun to use the method of more radically turning to ‘things’ as they present themselves in the field, in an attempt to sidestep the very analytic distinction between concepts and things with which fieldwork is habitually approached (Henare, 2006). According to Marilyn Strathern (1990), modern anthropology has traditionally taken as its task to unveil the social and cultural contexts, as frameworks in relation to which social life is elucidated. Under this approach, things, artifacts and materiality appear as mere illustrators or reflections of meanings which can only be derived from the framework itself. However, the more radical approach these authors employ, questions the enduring premise that meanings and things (their material manifestations) are fundamentally different and tests the limits of such assumption within their own ethnographic material. As a result, by refusing the separation between things and meanings, they turn their focus on how the material itself enunciate meanings (Henare, 2006). This shift in perspective allows to look at the physical environment as if it were another informant in ethnographic practice, for as the material can be now seen as a locus of inquiry in itself (Reichenbach & Wesolkowska, 2008).

Our work sits in line with this approach by following a specific object, that is, Post-It notes, as encountered in our fieldwork, so as to allow them to carve out the terms of their own analysis. As Henare argues (2006) this entails a different mode of analytical disclosure altogether: if things are concepts as much as they are ‘physical’, the question we would like to raise here is: what world -or workplace in our case- does attending to post-its allow us to conceive? -understanding conceive here in the two-fold sense of ‘engendering offspring’ and ‘apprehending mentally.

In this regard, we use Post-its as a thing that lies at the interface of the material and immaterial. This means not merely that they are material instances of a practice that carry within specific traits of a cultural or social context, as instruments that would, thus, illustrate, cultural characteristics. What we argue is that these things have in themselves a generative potential, which derives not from its instrumental or cognitive value, but from their distinctive properties as a thing in itself.

Slowness

Another point we want to raise concerns the rhetoric of speed and mobility that narratives of agility entail. Given the extent to which calls to fast deliverings and rapid cycles of progression lay at the center of agile frameworks, it seems relevant to ask how this practice is informed by the very choice of a specific medium of expression, and also to raise the question of which other possible paths are thus left behind.

Certainly, critiques to this modern inclination towards speed and movement are not new (See, for instance, Andrews, 2008, on the Slow Food Movement; or Hartmut, 2013, a critic of social acceleration under the logic of modernity). Lutz Koepnick (2014) brings several of these manifestations by revisiting the work of various modern artists and intellectuals from a perspective that does not reduce the notion of “slowness” to a mere reverse of “speed.” Instead of this, Koepnick brings new shades and layers of complexity into the work of these authors, that serve to overcome reductionists approaches which simply split the questions into the two poles of modernity = acceleration versus anti modernity = deceleration. Wondering whether slowness can be seen as something else than a banner for deceleration under a nostalgic view of a preindustrial past that does not exist anymore, he pictures it as an opportunity to re-signify the very concept of mobility and growth. From this view, the rhetoric of slowness would not be merely the reverse of acceleration, but this invitation to transform dominant understandings of movement and change. The work of Amazonian author Paes Loureiro (2015) offers an interesting counterpoint to the notions of progress and advancement that lie at the normative center of these rhetoric. The poetic attitude, which he defines as an essential feature of Amazonian identity, brings forth a notion of temporality and movement that move away from the sense of direction, speed and progress characteristic of modernity. His is a notion of time measured in intensity rather than velocity and a notion of space that is flesh out with intermingled narratives, visions and temporalities.

Based on the argument that the material bases of any practice inform its process of meaning-making, we suggest that the untapping of the possibilities that Post-it notes give rise to can also reveal which other modes of thinking, knowing and doing remained untried.

The remaining of this paper gives an overview of common practices within the Scrum framework and then offers an assemblage of images taken during fieldwork accompanied by a short descriptive sketch, aimed to bring to the front some aspects of the sort of epistemic culture that agile involves. Both the pictures and the vignettes are based on in-corporation anthropological research carried out at SIDIA, a Research and Development Institute located in Manaus, Brazil, during the first quarter of 2019.

Through this approach we aim to depict Scrum as a cluster of things, literally affecting and being affected between them, with Post-its being at the center of it. Instead of trying to answer the question of ‘what these things are”, we ask ‘what it is that Post-its make (us and others) do”.

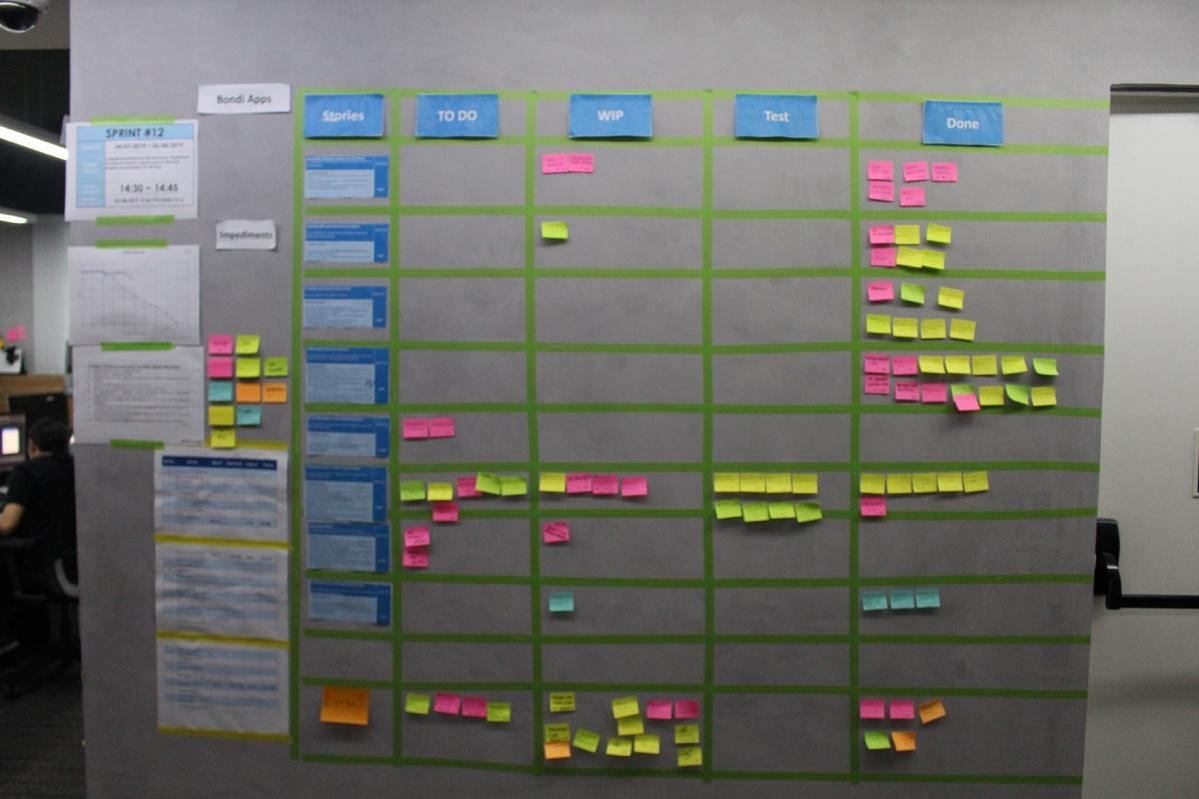

Things in Scrum

It all starts with a text, a document that lists all the features of the software in order of priority. This document is called the backlog. The backlog is solved in short cycles of development called Sprints. One sprint follows another, at the end of each one there is a deliverable, a small piece of software that correspond to some stories of the backlog. Each story is composed by description, acceptance criteria and ratings. Description is what should be delivered by the team, acceptance criteria is what defines that the story is done and the rating is an abstraction of the effort it takes to achieve that story. The points are scaled in a semi Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100), the logic is that 1 or 2 represent the story requiring less effort and the others are graduated using this as a reference (if it is two times more demanding, it has a score of 5 and so on). There are three roles in Scrum: product owner, scrum master and development team. Product owner writes the backlog and evaluates if the team has delivered the stories accordingly, development team works to implement the stories, i.e., develop the features of the software, and scrum master mediates the relation between the product owner and the team, as well as makes sure that there are no impediments for the team to work properly.

Scrum is articulated around different events, which are called “ceremonies” that bring structure to sprints, that is, to each of the incremental phases in which a specific project is divided. As any ceremony, these events are key to understanding the culture and the values that Scrum emphasize. These are: planning, daily, review and retrospective. Both sprints and ceremonies are aimed at “speeding up” the development process, by setting up the goals for success throughout the project. Thus, agile methodologies are aimed at producing scenarios of agile development (Sabbagh, 2014).

Under this frame, the artifactual character of the process is rendered preeminent. During ceremonies, teams come together around a number of objects, such as cards, Post-Its, slides and white boards to share their work-in-progress and set the next steps for the project. These objects are objects to mediate interactions: intended for transitory inscriptions, reifying ongoing work and repositionable information. At the same time they introduce a particular topology because they involve an opening up of a space which summons a particular arrangement of things and people.

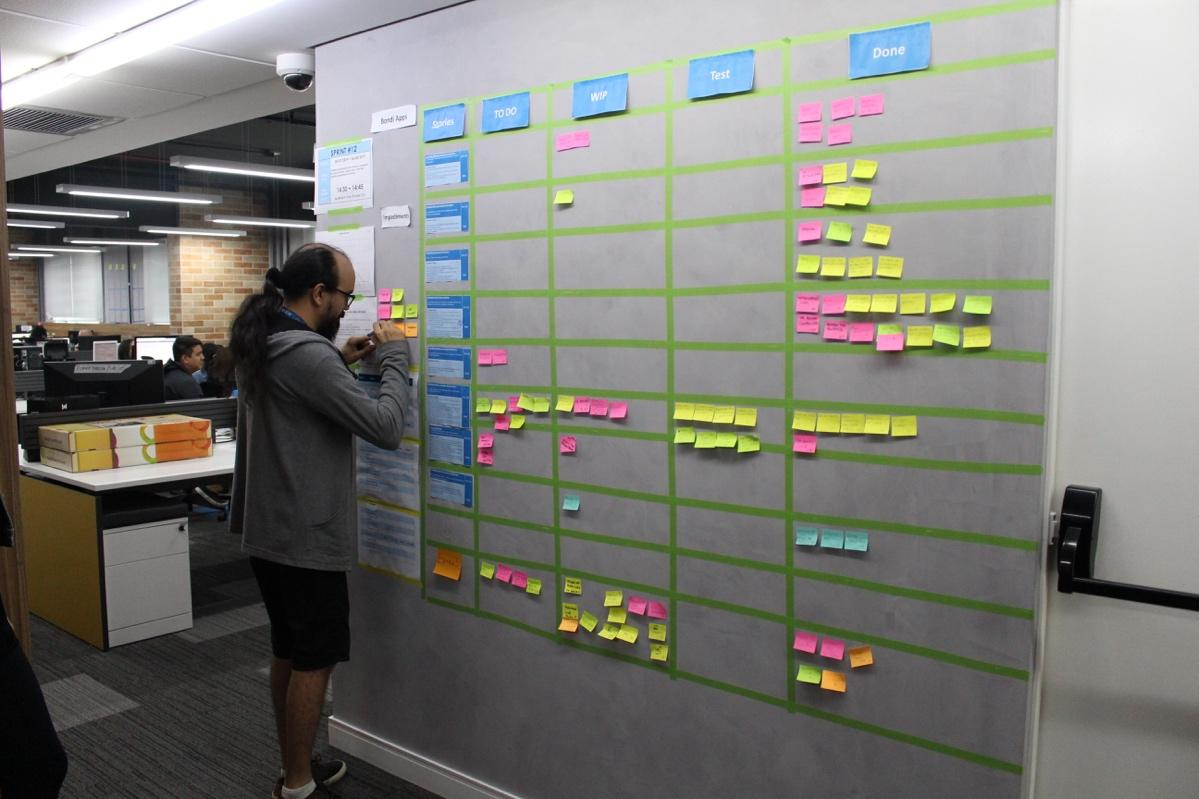

Figure 1. Photograph ©Juan Orestes, used with permission.

Among the common infrastructure and spatial lay-out of these environments, post-its, boards and paper cards visibly stand at the center of the work space, acting as “placeholders” around which teams gather and organize themselves. The rapid and iterative articulation of a specific project around sprints and ceremonies, strongly fosters the making and visual deployment of this kind of artifacts. They are oriented towards a deliberate organizational effect, for they are indeed mobilized to speed up change and iteration. In this regard, it is no accident that they become ubiquitous within almost any organization where agile frameworks are in play.

Here we focus on Post-it notes, which acquire a central role in these scenarios. Post-its in Scrum are objects used to think with, to the extent that they serve to express ideas at the same time that they shape them. By way of them tasks, doubts, activities and certainties become registered; at the same time, those ‘drops of thinking’ are determined by the physical characteristics of Post-its. While interacting with them, it is unavoidable to fall on a series of premises, as for instance, the need to be clear and to do one thing at a time, or the convenience of using the verb-noun structure and technical terms, to mention some.

Also, during Scrum sessions, Posts-its are moved from one column to another, making visible the progress that has been made. In this regard, they somehow materialize the speed with which the project advances, in terms of which the efficiency of the team is measured. They provide transparency to the project, by making visible on the wall what the team has committed to delivering and what everyone is doing. All these aspects, which are directly related to the properties of these things as things, fashion a certain kind of object and social relations, and ultimately engender a specific culture of knowing.

In the next section, we look specifically into three aspects that were rendered visible through our fieldwork: their transient nature, the succinctness they convey, and the mosaic character of the output and display.

VIGNETTE 1: TRANSIENT THINGS

Daily meetings are a central ceremony for team alignment within Scrum. These are short, 15-minute-meetings, usually done on a daily basis, aimed to prioritize and divide tasks, determine the progress of the project and identify impediments. Usually the core of the meetings can be summarized in two questions: what have you worked on since the last daily meeting and what will you work on until the next one. It is also an occasion to identify and share if there are any impediments hindering your work. Usually these meetings are held in a predetermined place and it is common to do them standing up to keep up the 15-minute format.

At SIDIA daily meetings are held around a wallboard that presents the different goals that have been assigned for the scrum team at the beginning of the sprint (called ‘stories’ in Scrum terminology) within a table that includes several fields designating the incremental stages of completion. Within agile methodologies, the use of boards as a working tool are quite common. In the case of Scrum, usually this board comes with four columns: stories, to do, in progress and done. The stories contain the description of the feature that should be implemented until the end of the sprint, a sprint runs with one or more stories; to do refers to the tasks that need to be done so that stories can be considered completed; in progress list the tasks that are currently under development; when they are finished they are moved to done. At the side of the board there is the burndown chart which indicates the pace at which the stories are being concluded. The burndown chart shows the progress of the sprint in a two axis cartesian plan: time represented in days versus effort represented as stories’ points. It indicates if the sprint has succeeded (if in the end of that cycle all stories are completed) or failed (if at least one of the stories can’t be completed). The tasks are chosen or moved from one column to another during the dailys, a meeting that occurs everyday around the board. These fields work as checkboxes for each of the stories. During the daily meetings, the checkboxes are filled with post-its notes describing shortly (maximum two or three words) the specific tasks which are being addressed and the progress made so far.

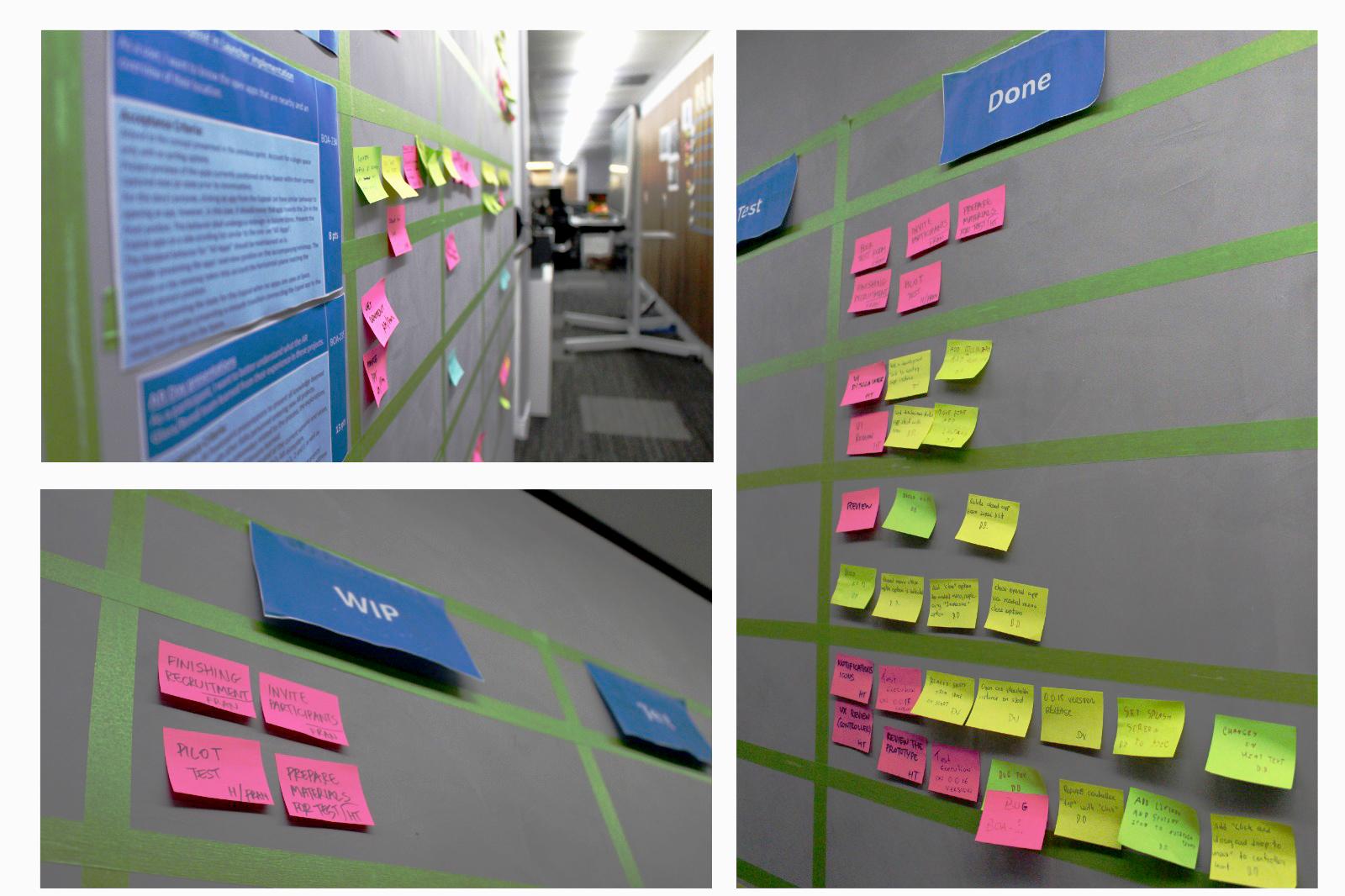

Figure 2. Photograph ©Juan Orestes, used with permission.

As a whole the board serves as a visual indicator of work progress. It is implicitly assumed that post-it should advance from the initial columns, to the final ones as the sprint goes on and, thus, it works as an early-warning mechanism that allows to rapidly detect hindrances in the overall time framework of a sprint. During these sessions no one actually reads the post-its -for indeed they are not really intended for that. Post-its are not used as content markers but as progress markers; or put in different words, it is their mobility through the board -and not what they ‘say’- what matters most.

Figure 3. Photograph ©Juan Orestes, used with permission.

VIGNETTE 2: SUCCINCTNESS

The practice of using post-it notes and sticking them on the walls of the workplace during Scrum ceremonies is very common within SIDIA and it is strongly related to principles of agility.

However, the requirement of fitting every task into the size of a Post-it note is not trivial, especially for beginners and people who do not have a background in design cultures, where the use of this type of elements is much more frequent. Shortening a text to the point of making it fit into the Post-it involves an exercise of succinctness that requires certain practice. At the same time, such succinctness of content directly influences the sort of effects they summon. Just as words within the paper have to be drawn up tightly -and there is no room for long-winded sentences, syntactic complexities or conceptual nuances- the interactions they tend to produce are also marked by brevity and conciseness. Also as with words, daily meetings are compressed into a small area, both in terms of duration and spatial display.

Figure 4. Photograph ©Juan Orestes, used with permission.

This effort of succinctness has a side effect in that it defines what sort of things are discussed and which are left unspoken. Since Scrum framework has a strong and rigid time pace, one sprint following other, usually there are few spots for reflection, questions and research about “why” something needs to be done. Scrum is a framework designed to get things done, sometimes at the expense of preventing any problematization of the project and its vision. The “post-it length tasks” shapes the behaviour of the development team as a challenge-oriented way of thinking since post-its are good to represent challenges that need to be completed, usually from one day to another, which is the time frame between dailys.

Also, the Agile Manifesto and the principles behind it, emphasize collaboration as a central element of Scrum. But the sort of collaboration that is involved in practice does not necessarily extend beyond the particular tasks that need to be accomplished during a sprint to the deeper layers of project value and purpose. In this regard, post-its generally afford more of an immediate, short-term and practical type of collaboration. They operate as an interface that mediate fast exchanges, which do not demand from team members to invest themselves in larger questions or concerns regarding the project.

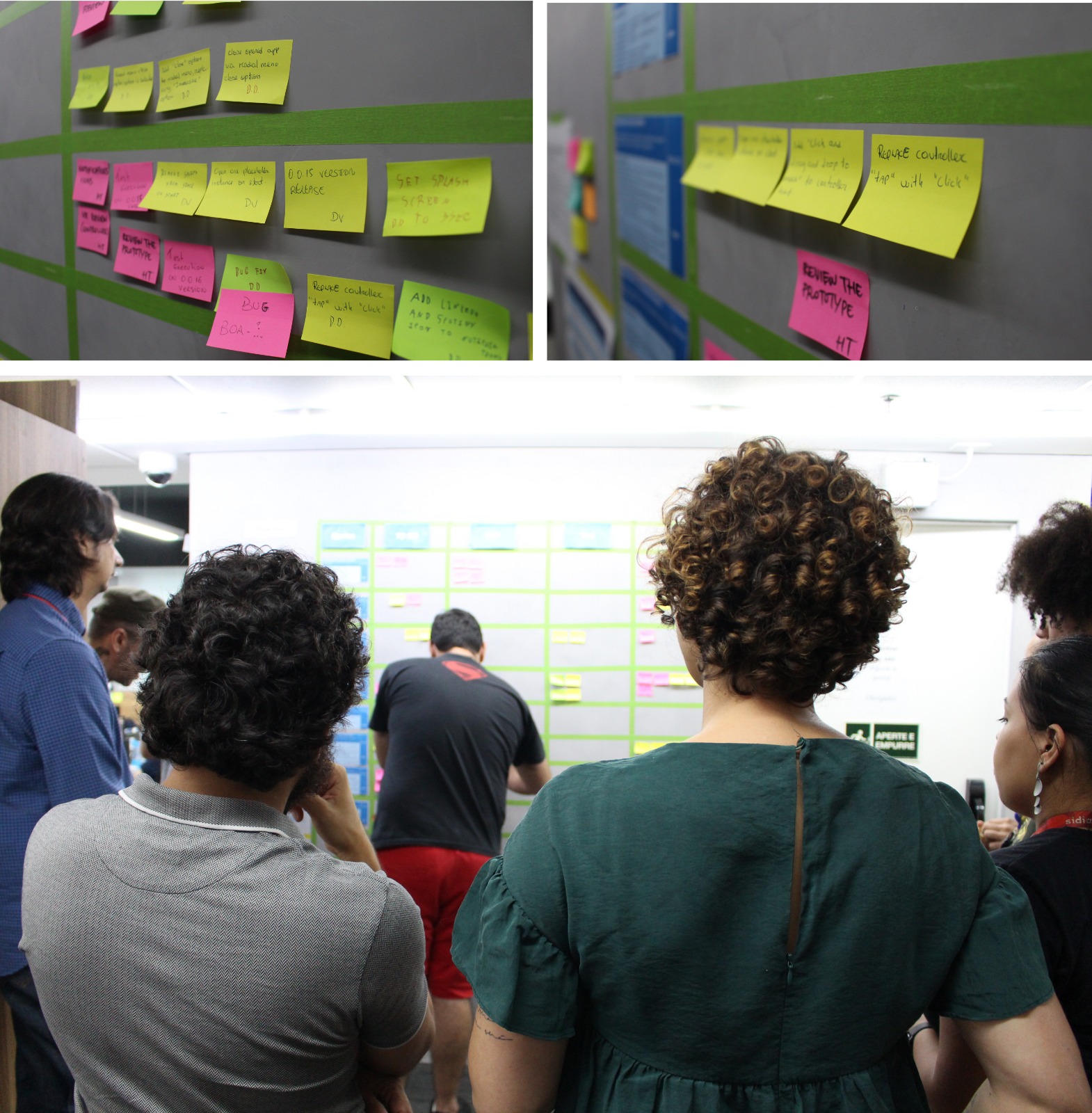

VIGNETTE 3: MOSAIC

Retrospective meetings are part of Scrum periodic ceremonies. They are held by the team and are conceived as an opportunity to look back in order to identify strength points and possible improvements to the work process as a whole. It is the only meeting which does not focus on the product, but on the process itself. At SIDIA these meetings are held after each sprint. The format they follow is rather informal aimed at creating a friendly atmosphere where teammates can speak more openly about questions regarding work, beyond the particular tasks they have been involved in. Also here Post-its play a significant role. Again using a wall, each of the colleagues write down in a brief manner both positive and negative things that they want to share with the group (one post-it per input) and stick the note onto the wall so that it is visible for everyone. A brief explanation is given and the next colleague does the same, until all the questions are hanging in front of us. Team members use that opportunity to share their thoughts and difficulties. No name is linked to the post-its, so at the end of the session the notes on the wall represent a collection of ideas, indeed, a collective picture detached from individual authorship. What matters, indeed, is the output as a collection and not the individual register of who-said-what.

This unfolds a particular approach to the notions of ideas and concepts. At the moment when ideas are sketched out under a word or two within the post-it note, it makes it count as a concept within the group, a process that happens between an interiorized thought and the exteriorized object hanging on the wall, involving a sort of material liminality (Gunn, W., 2013).

The sort of concepts thus created are not individual, but collective; post-its serve as transitional objects to turn heterogeneous inputs into similar and homogeneous material that can be physically handled. In this regard, these objects can be considered as “split entities” (Latour and Woolgar 1986 [1979]), whose main significance is not to represent individual input, but that constitute a material collection, with a value on their own. In fact, post-its work here as way of depersonalizing an object from a subject, that is, an objective reification of a subjective perception: as soon as an individual feeling or thought is written down, it is not a feeling or a thought anymore, but an objective information that can be shared with the team and registered in the project history.

Figure 5. Photograph ©Juan Orestes, used with permission.

DISCUSSION

These examples of Post-Its in practice alluded to so far reveal how the properties of Post-its as things inform the Scrum practice both physically and conceptually. We make the point that within Scrum culture, Post-Its notes can be taken as a generative concept, that is, as a thing that lies at the interface of the material and immaterial with a generative potential derived from its distinctive properties. In this regard, they can be considered as a key element of agile arrangements around innovation. It can be argued that “post-itly” ways of thinking and interacting are competencies sought under Scrum frameworks as a style of agile production and practical intervention with specific traits. In this work, we have focused on three:

First of all, working on and around Post-Its involves a compulsion towards progress. Vignette 1 illustrates the extent to which emphasis is put on work in progress and the processual character of iterations. Through the act of sticking post-its on the wall and moving them along the table as the sprint advances, they are transformed into a proxy for movement and progress rather than instances of knowledge.

The above is closely related to the succinctness both of the object and social relations that are enacted through them. By the continual exteriorizing of concepts in nugget-sized forms, post-it notes turn into pieces that can be worked on by teams with brevity and conciseness. These pieces have a somehow “slippery” nature giving shape to a shifting constellation of relations that are continually in flux.

Finally, the mosaic display that results from Post-its usage is also preeminent within Scrum practices. As material manifestations visible to everyone, they turn from interiorized ideas to materialized concepts that are now collective things which enter into a process of juxtapositions and montage. This gives way to a mosaic way of thinking, that places the emphasis on relational and collective thinking, rather than in individual outputs. This sort of micro-transformation from ideas to information that is fit-for-working and fit-to-be-seen represents the kind of process to which abstract notions, ideas or concepts are subjected under Scrum. The very materiality of post-its enable specific ways to set and to consolidate knowledge around a project, understood as the product of groups, as opposed to individual minds.

(Fr)agility

These traits set the conditions for a cultural practice with very specific characteristics. However, to the same extent, they also define the field of possibilities that remain outside of these contours. The question now is what is thus is cut off from the “post-itly” way of knowing.

The high adherence of the digital industry for agile approaches reinforces a specific reason, the “proleptic reason”, which Boaventura defines as a way of thinking that understands the future as a linear, automatic and infinite continuation of the present. Under this reconfiguration of time and space lies, implicitly, a notion of progress along a single temporality in which the emphasis is placed on becoming rather than on being. Thus, since the progress is linear, the question is not about where are we going but how fast can we get there (Souza Santos, 2002). Being the first to release a new technology, a new feature or a new service is the key point for success within this particular mindset. In the same way, short cycles of planning, development and release, in opposition to detailed planning, and mass production and distribution, can be understood as an extreme compression of space and time, a phenomenon that according to Harvey characterizes modern capitalism. The acceleration in the rhythm of production and consumption cycles has been gained at the expense of space, or rather, upon the presumption that spatial variables -those related to social structures, power relations or affects- can be suppressed (Harvey, 1992).This flattening of space under a notion of temporality understood as a single directional vector leads to an illusion of control. In this regard, Han argues that this modern notion of temporality is contingent upon control metrics that seek to assign always quantifiable values and establish casual relations along a chain of elements. When actions are subordinated to a process of calculation, governance and control they become transparent, thus, operational (Han, 2015b). If this serves to stabilize and speed up the system, it also erases otherness and difference.

According to the author, one of the realms in which this becomes more noticeable is language. In order to remove its intrinsic ambiguity, modern organizations rely on a type of language which is as formal and efficient as possible, in order to turn it operational. A retrospective in which all the feelings and thoughts need to be shaped to fill in a single post-it guarantees that otherness, doubtness and difference will be highly minimized. Thus, the search for transparency leads to a systematization both of language and social interactions to avoid any frictions that might naturally arise from moments of forgetfulness, discontinuity, doubts or intuition. Moments of reflection and theoretical thinking give way to technique because theory in itself constitutes a negative substrate of things, that is, a result of an operation that goes against what is given, thus, separating the continuum and revealing hidden relationships between variables and objects (Han, 2015b).

As said before, Scrum is a framework to get things done, it doesn’t lead well with research, reflection or theroization, in fact, there is no room (in any ceremony or during the sprints) to do so. In this regard the succinctness expected under agile landscapes -both in language and in social interactions- can be seen as an erasure of negativity, in the sense that Han uses the notion, that is, as a way of fencing off practices of production and development.

But what happens, for instance, when more thoughtful and slower responses are needed in moments of uncertainty as they unfold into the Scrum process? Although it is beyond the scope of this work to explore the multiple unfoldings of this question, we would like to set forth some ideas of what such a possible diversion or slowing down could look like.

Ethnography as devaneio

Differently from a perspective that conceives movement as a shift from one point to another, or an advancement along a temporal vector marked by a direction, movement can be seen as a field of intensities, that is, as a practice of immersion, of absorbing, of engaging deeply in the present moment.

The Amazonian author Paes Loureiro (2015), in his analysis of what constitutes amazonians’ identity offers an interesting approach for re-framing the notion of movement and, in particular, what it means to look at processes of slowing down not as a delay in happening but as a way of intensifying and enriching the present.

At the risk of gross simplification, if during modernity time was conceived primarily as a vector of movement, change and progress, in contrast to space which was the fixed, the static, that which remains, in Paes Loureiro’s work space becomes prominent. Through a “poetic way of thinking” -which he defines as an attitude that is essential to the identity of the native and it is evidenced by “a wonder at everyday reality” (Loureiro, 2015: 121)- space itself becomes the locus of mobility, while time is no longer a directional vector but an intensional one. Thus, the concept of devaneio (Portuguese word, literally meaning daydreaming) becomes central, which he defines as a vague and contemplative attitude associated with simple being, pleasure and presence in the face of reality. Put it differently, a sort of receptivity to the environment, almost a reaction of the self through the senses propitiated by the Amazonian landscape itself and the relationship that the native maintains with it.

In this regard, devaneio is movement; a movement which is defined not by the displacements it brings, but by the intensities that traverse through it. To the extent that it is a way of expanding the present, devaneio involves slowness and permanence because the present takes place primarily in space, in the here and now; It is, though, an enriched space, no longer the simple fixed and static container where things happen, but the soil where different possibilities, intensities, narratives and visions coexist and intersect.

The way that Loureiro understands the relation between time and space is clearly opposed to the way that modernity approach these instances. According to Harvey (1992), considering the way of production and the dynamics of capital since the end of last century, time was used, first, to take hold of space, and then to liquidate it. Agile practices solved a problem of the old paradigm of production, which was born in large scale factories. This paradigm was strongly dependent upon questions of space (such as logistic, distribution, time as an input for physical production, to mention some), and it became outdated and incapable of handling the dynamic of continuous change and technical improvement that software development demanded. To address these challenges, agile practices were introduced and gained legitimacy in the software industry, although at the expense of causing the “super valuation” of time over space.

So the question we would like to raise is this: how can the concept of devaneio be re-signified in the context of current rhetoric on agility and innovation that have taken hold in a large number of institutions and organizations? Rather than answering this question, here we set the scene for further thought and discussion.

First, a claim for slowness within organizations should move away from a notion of slowness which conflates it with deceleration. In this sense, a culture of slow innovation would not be the opposite of acceleration and advancement but an enrichment of the present experiences; to slow down is to intensify the present not necessarily to reduce speed.

Second, to the extent that, in this sense, slowing down involves an enrichment of the present’s experiential and conceptual density, we need to design mechanisms that allow for devaneios and processes of record, tracing-out and immersion, that can coexist with those of production and development.

It is important to highlight that the notion of devaneio implies a non-objective relation between time and space. It still logic, but the axioms of this logic are grounded on a relation constructed between the self and the place. Instead of time ruling over space, it’s the space that determines time, that is, the pace of time is shaped by the self within the place.

A claim for slowness, or a claim to regain an enriched present, will lead us to rethink our relation with space. Although at first it might look as a question of time, it is in fact a concern around space, around seeking forms of landing and re-encountering ways of belonging; like the notions of ancestry, legacy and heritage, we would, thus, need to make sense of time and temporality considering questions of space, the others and the collective.

Finally, as anthropologists working within corporations, we can ask how this approach to innovation culture in organizations can benefit from ethnographic skills and practice. Similar to the way that Paes Loureiro defines the Amazonian poetic attitude, the anthropologists typically immerse themselves in their subjects of study. Likewise, the ability to transit across registers, narratives and perspectives within a “multifaceted present” can certainly be considered a cornerstone of ethnographic practice.

Within anthropology, the figure of the researcher doing fieldwork has always been closely tied to the rhetoric of engagement and commitment to their subjects of study and their experiences in the field. There is almost a sort of ethical code embedded in anthropology which measures the work of an ethnographer to the extent that he is capable of entering in a flow of affections -of taking and being taken by- among the people studied and turning that experience into the fuel of purpose and action. That which distinguishes ethnography from other research techniques has to do with the ability of entering in a circuit of connections immanent to fieldwork itself, that brings about a change for both parts. In this regard, when anthropologists are urged towards autonomy, in practice this has more to do with the demand of being true to the rapport of forces in which they find themselves enmeshed during fieldwork, than with the need to remain independent and separated from any influence. So, at the core of an anthropologist’s skills there is this capacity to affect and be affected, based on the acknowledgment that theory is never a value-free zone and that transparency cannot ever hover above embodied lived experience.

So we can ask how this understanding of autonomy and transparency based on ethnographic practice, which is marked not by disentanglement, but by skills strongly rooted in experience, can be re-signify in the context of innovation culture. From this view, the sort of mechanisms we might be willing to search for are not the ones that remove “negativity” from life and interactions but those that encourage processes of immersion within the subject of study, enriched interactions among the actors involved and ways of letting oneself be affected by those; in short, mechanisms that multiply and strengthen the articulations between beings and things.

CONCLUSION

Our aim has been to illustrate how agility is materialized through the use of post-it notes and how these flesh out agile practices along specific traits which derived from the thing’s properties.

In this regard, post-its can be regarded as a key element of agile practices among many organizations. Even in contexts where physical post-its are being replaced with technologies that allow to plan, manage and monitor Scrum practices digitally, it can still be argued that “post-itly” ways of thinking and interacting are competencies sought under agile organizational frameworks, which define forms of knowing and doing things with very specific traits. At the same time, we have made the argument that these things also set the field of possibilities that remain outside of the world they help conceive.

In asking what it is they do and do not afford, we discussed how the notion of slowness can be re-signified to go beyond simplistic divisions between acceleration and deceleration in the context of current rhetoric on agility and innovation. To so so, we considered an amazonian approach, as developed by Loureiro, in which slowness is seen as a way of intensifying the present; thus, it offers a counterpoint to the modern notions of progress and advancement. Finally, we raise the question of what sort of mechanisms would allow this to happen and ended up with a brief insight into how anthropology and ethnographic practice can be enlisted for this purpose.

REFERENCES CITED

Andrews, G. (2008). The Slow Food Story: Politics and Pleasure. London: Pluto Press.

Appadurai, A. (1986). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barton, B. (2009). All-Out Organizational Scrum as an Innovation Value Chain, 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, pp. 1-6.

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK : Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Cefkin, M, (ed). (2010). Ethnography and the Corporate Encounter: Reflections on Research in and of Corporations. Berghahn Books.

Conboy, K. (2009). Agility from first principles: reconstructing the concept of agility in

information systems development, Information Systems Research 20 (3), 329–354.

Dybaå, T., and Dingsøyr, T. (2008). Empirical studies of agile software development: A systematic review. Information and Software Technology, 2008.

Gunn, W., Otto, T., Rachel, Ch. (2013). Design Anthropology. Bloomsbury UK Academic.

Han, Byung-Chul (2015a). The Burnout Society. Stanford University Press. Stanford.

Han, Byung-Chul (2015b). The Transparency Society. Stanford University Press. Stanford.

Hartmut, R. (2013). Social Acceleration. A New Theory of Modernity. Columbia University Press.

Harvey, D. (1992). Condição pós-moderna: Uma pesquisa sobre as origens da mudança cultural. São Paulo: Loyola.

Henare, A., Holbraad, M., Wastell, S. eds. (2006). Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. Routledge.

Holmes, D. R. and Marcus, G. E. (2008). Cultures of Expertise and the Management of

Globalization: Toward the Re-Functioning of Ethnography. In Global Assemblages:

Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Hron, M., Obwegeser, N. (2018). Scrum in Practice: an Overview of Scrum Adaptations. Conference Proceedings: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Iivari, J., Iivari, N. (2011). The relationship between organizational culture and the deployment of agile methods. Information and Software Technology 53, 509–520.

Ingold, Tim (2000) The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill, London: Routledge.

Inman, R. A. (2010), ‘Time-based competition’, in Encyclopedia of Management (online document).

Knorr-Cetina, K. (1983). The ethnographic study of scientific work: towards a constructivist interpretation of science, in K. Knorr-Cetina e M. Mulkay (orgs.), Science observed: perspectives on the social study of science, Beverly Hills, Sage.

Koepnick, Lutz (2014). On Slowness: Toward an Aesthetic of the Contemporary. Cambridge University Press.

Kvangardsnes, Ø., (2008). In The Scrum: An Ethnographic Study Of Implementation and Teamwork. Institutt for datateknologi og informatikk.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B., Woolgar, S., (1986). Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press, [1979].

Loureiro, J. J. P. (2015). Cultura Amazônica – Uma Poética do Imaginário (1994). Editora Valer.

Miller, D. (1998). Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pham, A. (2012). Scrum in Action:: Agile Software Project Management and Development. Course technology PTR, Boston.

Raymond, E. S. (1999). The Cathedral and the Bazaar. O’Reilly Media.

Reichenbach, Lisa & Wesolkowska, Magda (2008). All That Is Seen and Unseen: The Physical Environment as Informant. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, 160-174. https://www.epicpeople.org/all-that-is-seen-and-unseen-the-physical-environment-as-informant/

Sabbagh, R. (2014). Scrum: Gestão ágil para projetos de sucesso. Casa do Código.

Santos, B. S. (2002). Para uma sociologia das ausências e uma sociologia das emergências. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 63, 237-280.

Steen, M. and Dhondt, S. (2010). Slow Innovation. Paper presented at EGOS 2010 Colloquium, Lisbon.

Takeuchi, H. and Nonaka, I. (1986). The New New Product Development Game: Stop running the relay race and take up rugby. Harvard Business Review.

Urban, Greg & Koh, Kyung-Nan. (2012). Ethnographic Research on Modern Business Corporations. Annual Review of Anthropology. 42.