This paper discusses the benefits and challenges of participatory photography as ethnographic evidence and how as researchers we can “read” the evidence our participants create. Drawing on examples from an ethnographic study examining concepts and constructions of community on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, I examine how we can interrogate photographs as data rather than factual evidence. Adages such as “the camera doesn’t lie” support the view of photography as a purveyor of truth. Photos accompanying journalistic dispatches from far-flung outposts around the world are seen as authentic evidence of real-world situations. Amateur videos of people’s life experiences are filmed on smart phones and then posted to YouTube to be taken as authentic representations of life events. Early ethnographic uses celebrated photography as the ultimate tool for showing that anthropologists had actually “been there,” displaying the exoticism of other cultures in factual black and white. However, photography has never been a simple representation of the truth—it is not cameras that make photos but people, with all their personal quirks, cultural beliefs, and subjective experiences in tow. Photographs always provide at least two kinds of evidence—what is inside the frame and what is outside the frame. As researchers working with participatory photography, one of our roles is to determine the importance of what is outside the frame. We must ask whether this unseen evidence is as valid—or more so?—than what participants keep inside the frame. In the age of Snapchat, Instagram and other social media, researchers need to interrogate participant-created photography carefully and methodically. We must question how we interpret photographic evidence that has been manipulated by its creators and how that manipulation affects our interpretations of the evidence. Participant-created photographs add valuable depth and complexity to ethnographic research but we need to ask how participants may conceptualize their photographic creations and how context—culture, socioeconomic status, gender, location, etc—impacts the evidence participants create. And in turn, how those same contexts influence our interpretations of participatory photographic evidence.

INTRODUCTION: A (VERY) SHORT HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY

Early ethnographic uses of photography celebrated it as the ultimate tool for showing that anthropologists had actually “been there,” displaying the exoticism of other cultures in factual black and white. Anthropologists like Franz Boas and his student Margaret Mead saw photographs as a way to capture factual records of cultures that were going extinct. Visual recordings, whether still photographs or film, could salvage and preserve for posterity a cultural ceremony or way of doing something, such as a demonstration of Torres Strait fire making or Balinese parenting styles. These visual records would then “act as a template for the process, allowing it to be reproduced, rather like following an instruction manual. Visual recording ‘saved’ the event in some reified sense” (MacDougall 1997:282). This viewpoint has changed dramatically and anthropology’s relationship with photography and film, and the continued evolution of visual anthropology, has been well addressed across anthropological and sociological literature (see, for example, Edwards 2015, Pink 2007, and MacDougall 1997). For my purposes here, what is important to remember is that photography has never been a simple representation of the truth—it is not cameras that make photos but people, with all their personal quirks, cultural beliefs, and subjective experiences in tow. Photographs are evidence of how people feel, what they think about and how they think about it, as well as how they make their way throughout their worlds (Edwards 2015).

Before I go farther it is important to note why I limit my discussion here to photographs rather than photographs and film. As I noted above, both photographs and film have a long history in anthropological research. The reasons I focus on photography are not due to some deep theoretical belief but instead merely practical—while I admire and am fascinated by the use of video and film in ethnographic research, I have not actually done it myself. I have analyzed films and used them to teach and discuss anthropological concepts and theories but I haven’t used the medium myself in my research. I choose to focus on photography because that is where my experience lies. For broad discussions on film and video in ethnographic research that are well beyond what space and my understanding allow, see, for example, MacDougall 1997 and particularly Barbash and Taylor’s 1996 conversation with Judith and David MacDougall about ethnographic film methodology.

INTERROGATING PHOTOS AS DATA VERSUS FACTUAL RECORDS

Consider this iconic photograph (Figure 1) of one of anthropology’s founding fathers, Bronislaw Malinowski, during field work in the Trobriand Islands in 1918. For years anthropology students and others likely took this image at face value—evidence of the eminent anthropologist in the field, studying the “exotic” Trobrianders. Later images like this would be critiqued as proof of colonialism and its associated evils. Even critiques like this take the photo at face value, as evidence of a particular truth and that the image is a factual record.

As Alex Golub so succinctly put it in a short analysis of this photo, “If there’s one picture that epitomizes White Guys Doing Research, it’s this one. The canonical author of the canonical book, naked black people, white guy in white clothes being White” (Golub 2017). However, if we take a step back and instead of considering the photograph as a factual record of some kind but instead data, an entire world of inquiry opens up. Rather than taking it as a record of some truth (an example of colonialism of early anthropology or a record of authentic Trobriand Island drinking vessels) we can interrogate not only the data contained in the photograph but also the data that is outside the frame—in what circumstances the photo might have been made and what Malinowki’s thought process might have been. Although we can no longer ask Malinowksi about the photograph and the making of it, we are fortunate to have Malinowki’s diaries and field notes, as well as interviews with field research assistants and others who knew him to give us insight into the man and what he might have been thinking when crafting a photograph like this. As Golub further reflects,

Figure 1. Bronislaw Malinowski and Trobriand Islander men. Courtesy University College London archives.

The thing that most people don’t get about this picture is that at least 30% of it is cosplay. What surprises me about this image is that many people view it without any sense of irony—as if it had not been posed, as if Malinowski didn’t notice the difference between himself and ‘the natives’, as if Malinowski was unaware of what his lime spatula looked like (emphasis in original, Golub 2017).

When viewed from this perspective, the photograph becomes much more than “factual” evidence but evidence we can examine for the maker’s thought process, the positioning of White male researchers in 1918, Malinowski’s personality, and more. We can also interrogate it for evidence of contemporary thought and reactions to photographs made during the peak of colonialism. When we think of an image in these terms, a photograph is worth more than 1,000 words. Of course, photographs have never been simply factual records, even though some anthropologists at one time may have thought of them as just that. They’ve always been data as well as a record that someone was in the place and time with the people they said they were. Indeed, we interrogate old photographs as well as contemporary Instagram posts for evidence in our research on a regular basis. However, there is, I think, an important distinction between the conclusions we make when reviewing photographs in absence of their makers versus in concert with their makers. When the makers (our research participants) themselves explain their photographs and the motivations and meanings behind them to us, we very clearly and deliberately put the research participant—the knowledge holder—at the center of the frame in our inquiries.

PARTICIPATORY PHOTOGRAPHY AND ETHNOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

Ethnography, if we break the word down, literally means writing about people, so it might make sense to wonder how we can do “ethnography” without words, but with pictures instead. The fact is, ethnography is about observation, and our vision plays a vital role in that observation. However, when it comes time to analyze our observations, we turn to words and theories about what we have seen, or at the most micro level we explore theories about words. However, this kind of analysis belies the fact that our observations in many cases were made with our visual faculties. How, then, to share what our eyes took in and our brain and psyche processed? How do we know if what we see is the same as what someone else sees? Is the blue of the sky I see the same as the one the woman with the long black hair sitting across the way sees? Consider an argument my mother and I had over several years about the color salmon. I argued that it was a pinkish, rose-hued color. She argued it included much more orange than that. She is an artist, so she had artistic color theory on her side, but I just couldn’t understand how she could say the color salmon was orange-ish. It’s the color of a piece of salmon, which is definitely not orange; I wondered how she could possibly make the argument when we were looking at the same color. Well, a few years later she had eye surgery and lo and behold, she came to me and said that I was right, salmon was in fact pinkish and didn’t have any orange in it at all. It turns out we were seeing a different color when standing side by side looking at it—the early cataracts she had had created a yellow film over everything she saw. It is my contention that although we assume, when reading, that we are reading “the Truth,” or at the very least the author’s truth, there is always a sense of fiction within any account. The brain and memory is a complex, fickle, and creative thing. As readers, whether we are reading words or images, we impose our own interpretations and our own vision, if you will, on the author’s creation. So, I can tell my story but each person who reads it is going to “see” that story differently based on their own experiences and opinions.

At its best, ethnography attempts to get at that very personal, internal, embodied experience of both participants and researchers. Incorporating participatory visual research methods into research is one way to get at those deeper, hidden meanings. By using visual materials—in the case of this paper, photographs—produced by participants we create a richer, more layered story than if research data is gleaned only from interviews and written observations. If Willy Wonka’s smell-a-vision actually existed, that would be another fantastic enrichment to ethnographic research, but alas, no one seems to have developed it yet, so photographs will have to do. Photographs not only bring more richness and depth to our research evidence but they also facilitate relationships with people, helping to bring us closer to our research participants through shared visual stories (Edwards 2015:248). Photographs can bridge time and space and help us place ourselves into our research participants lives and experiences in a deeper way than only words could.

Details of My Participatory Photography Project

Most of the photographs I reference in this paper were made as part of a larger ethnographic study of community, place, and identity on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia conducted between June 2011 and August 2012. I went to Salt Spring to try to understand how people define, imagine, and create place, and why creating place matters. On an island known for its physical beauty as well as an “alternative” approach to social relations and politics, Salt Spring is also a place where economic development competes with environmental preservation, affluence intersects with poverty, and residents grapple with concepts of insider versus outsider. Definitions of Salt Spring Island are complex and often contested and competing, both between residents and between residents and outsiders. Evidence I gathered from traditional participant observation as well as that created directly by my participants with their photographs helped me to explore these contestations of place and examine how people mobilize various means to define Salt Spring Island for themselves.

My goal with the participatory photographic aspect of data collection was to recruit additional participants who were not part of my core group of participants, not only to widen my pool of research participants but to also test whether or not participatory photographic methods brought forward different types of data than simply traditional participant observation and interviewing. Initially, I put a call out on the Salt Spring Exchange, an electronic message board used on a regular basis by many residents, for participants, asking for people who wanted to tell, in pictures, their story of Salt Spring. I had ten people respond to my call. I sat down with each person who responded for about an hour initially, explaining my project and interviewing them about Salt Spring, how they came to live there, and their impressions of the island. I included these interviews in the final data for the research project, however, not all people who responded ended up participating fully in the photography aspect of the project. Two people took photos but I was not able to successfully schedule a second meeting with them to review their photos. Two people took part in the initial interview but opted not to participate further. Ultimately six participants completed photographs and agreed to share them with me for this research. I asked these participants to take photographs as if they were going to tell someone who had never been to the island about Salt Spring, their experiences on the island and what the island is like for them. The majority of my participants took their photographs over several months in late winter 2011/early spring 2012. After our initial meeting, I sent participants away—all but one with their own cameras—to take the photos on their own time. One participant didn’t own a camera, so I supplied her with a disposable one.

In visual ethnography literature this approach—having participants provide pictures of a particular subject—is generally described as photo voice. However, that can encompass photographs that participants have made outside of a specific research project—for example, all the pictures they’ve taken of their dog since they day they adopted her rather than pictures of a specific research question, such as “can you document your dog and how your dog impacts your life?” Therefore, I like to think of it a bit differently and use the term participatory photography. Participatory to me implies an active role on the part of the research participant, which is not always the case with photo voice. Rather than imposing my presuppositions on the experience and telling my participants what photos they should make, I wanted the participants to lead the process, not only in what and how they chose to photograph but also within the interview process itself when we discussed their photos, so that they were working with me to build a shared understanding, of a shared experience, of place. As Sarah Pink notes,

when informants take photographs for us the images they produce do not hold intrinsic meanings that we as researchers can extract from them… they are derived from photographic moments that were meaningful to the people who took the photographs … when our informant-photographers discuss these photographs they place them within new narratives and as such make them meaningful again (2007:91)

Thicker Description: The Benefits of Participatory Photography

The photos that make up my visual ethnography of Salt Spring are not just pretty pictures, however, but a concerted effort on my part to build a better, and to borrow from Clifford Geertz, thicker ethnography. An ethnography should feel real somehow, it should transport the reader to that place and time, much like a good novel. By incorporating my participants’ photographs, I believe I created a richer, thicker description of Salt Spring than would exist without the photographs my participants made and the meaning we made from them. Some research shows the part of the brain responsible for processing visual information developed evolutionarily before the parts that process verbal data, meaning that “images [could] evoke deeper elements of human consciousness than do words; exchanges based on words alone utilize less of the brain’s capacity than do exchanges in which the brain is processing images as well as words” (Harper 2002:13). Reflective of this hypothesis, the work with my research participants elicited what I would describe as more layered, more deeply thoughtful conversations when we were reviewing their photographs than when simply talking with no visual cues.

It also made a difference to my participants that they were sharing photographs they had made themselves, in an order and within a story they were driving. They all shared that they felt intimately involved in the research and that it was more interesting for them than had I just sat down and asked them questions. They also felt more in control of their story than had I been leading things more directly. Other researchers have experienced the same benefits with their research participants when using participatory methods. Elizabeth Faulkner and Alexandra Zafiroglu note that their video “participants experience a more heightened engagement in sharing their experiences with us than they do when we film, as they take an active role in constructing how they will be portrayed… They are creating intentional representations of who they want others to imagine them to be” (2010:117). In his work studying the Danish concept of hygge, Jonathan Bean found that bringing participants into his data collection process shifted the power dynamic and created an alliance of sorts to document evidence when he and his participants shared the task of filming their homes while discussing hygge. He notes that he “found the mere act of asking for assistance with data collection to subtly shift the power dynamic between researcher and participant. Upon reflection, I found that the researcher and participant became allied in their task of documentation” (2008:106). The fact that participants get to participate in the research process and shape evidence that is about their own experiences and the meaning they imbue those experiences with is an important one. Adding their voices in such a direct way lends credibility to research evidence because it is first-hand and participatory, not one-sided and viewed solely through the researcher’s lens.

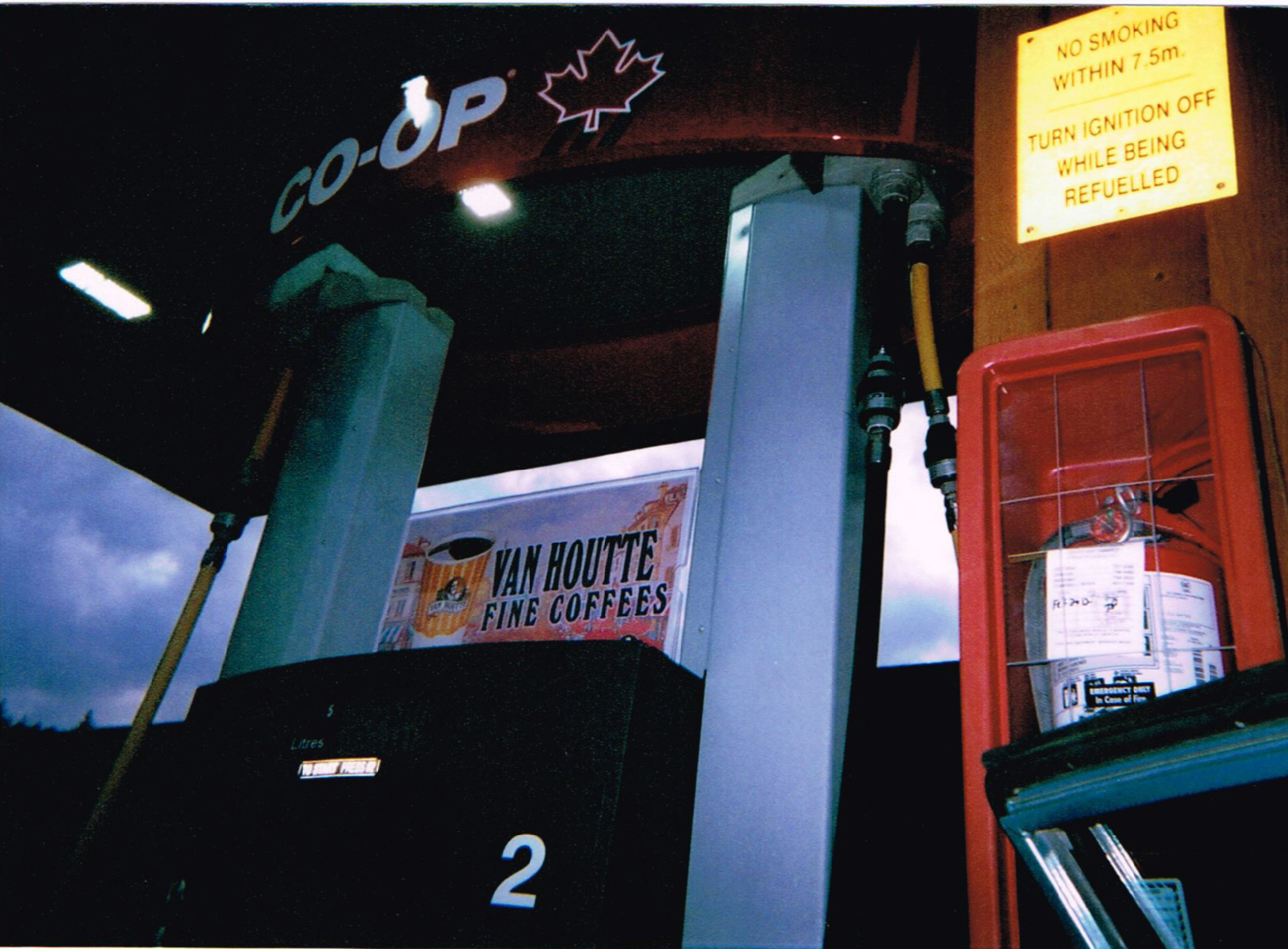

This shifting of power dynamics can be one of the greatest benefits of using participatory photography, if a researcher uses the method with that in mind and truly allows participants to drive the research process, especially during the interviews about their photographs. As Josh Packard discovered in his participatory photography work with homeless men in Nashville, going through every one of a participant’s photographs and letting the participant drive the interview process allowed for information he hadn’t expected to come out, information that gave more depth to his research (2008:68). I approached my interviews the same way and had the same experience of unexpected information arise. One of my participants, Tanya, didn’t own a camera or smartphone so she used a disposable camera I provided. She included images of natural beauty and popular areas in town as many of my other participants did but she also some photos that were out of the ordinary, including one of the gas station.

Figure 2. By Tanya. Co-Op gas station, Ganges, 2011. Used with permission.

I was surprised to see the photo because I knew Tanya didn’t drive but I still expected her to discuss something about the price of gas on the island and how people are always waiting in line at the gas station during busy times, but I left the space open for her to tell me why she took the photo and what it meant to her. Leaving that space open for her to drive the interview opened up an entire discussion about people who had access to cars on the island and who didn’t, the hitchhiking tradition on the island and the various people she’d met and experiences she had had while hitchhiking. Tanya felt a sense of kinship with many islanders who also had to hitchhike to get around the island but it was a feeling, she said, that was becoming more and more fraught for her as time went on. As the island became more affluent, the gas station didn’t just represent an area of life she chose not to participate in (having a vehicle) but was coming to represent a feeling of isolation and being an outsider on an island she had lived on for more than thirty years. Tanya lived in a small apartment and worked several jobs, fighting hard to make ends meet, a situation common to many people on the island, including, she said, her friends who worked at the gas station. She went on to describe the thin line between getting by and not being able to afford food that many people face on Salt Spring and how things had changed. Tanya described a past where this struggle felt more communal, where people shared extra food from their gardens on a regular basis and there were less people who fell through the cracks. As property values increased on the island and more new, affluent people moved in, Tanya felt less welcome and less at home. In fact, Tanya ended up moving away from the island shortly before I finished my research and has not returned. All of this information, contained in hours of conversation, came from a single photograph of the gas station. It was unexpected, rich, valuable evidence of Tanya’s intimate, personal experiences and feelings that I never would have gotten had I gone into the interview with a specific set of questions that I was set on asking. By letting Tanya drive the conversation and create meaning for me, sharing her feelings of belonging and exclusion, struggle and empathy, as well as frustration and anger, I turned over power to her to tell her story in a way that made sense for her.

Some Challenges in Participatory Photography

Participatory photography has many benefits as an ethnographic method, but it is not without a variety of challenges. First and foremost from my perspective is the issue of confidentiality. Confidentiality is always of concern when doing any kind of research but when you introduce a camera into the mix it only becomes messier. When we make photos and videos as researchers, we think through the ethical implications of who and where we are photographing or filming. We have been trained to keep confidentiality at the forefront of our minds when doing research—we should know instinctively when it could be inappropriate to take a photo or when we need to ask more than once, to make sure people are completely comfortable and informed when giving their consent to be photographed. However, when we transform our participants into participatory research participants who are actively producing material we will use as data, we need to pay special attention to ethical considerations like confidentiality and appropriateness of who and where they are making photographs. We need to ask whether our participants might be taking photographs of people without those subjects knowing or whether we might be exposing something photographic subjects do not exposed, even unknowingly. Children are photogenic and often the most approachable of our subjects, but photographs of minors hold even more ethical dilemmas than those of adults. Before embarking on a participatory photography project it is important to have a well-defined set of ethical guidelines and to go through them in detail with each participant to make sure they understand them and will honor them. A discussion of the ethics involved in ethnographic photographs is a long and complex one but suffice to say here that I tend to make it a practice to err on the side of caution—if I’m unsure about how a participant would feel about the inclusion of a photograph or if I don’t know explicitly that a person has given permission for their image to appear outside of the privacy of an interview, I do not share it. I include these practices in guidelines for my participants who are making photographs and ask them to sign an agreement stating they’ve understood and will follow the guidelines. Another approach to ethical guidelines is to develop them in concert with your participants. This can be extremely useful in making sure that people comply with ethical guidelines because they have had a hand in creating them and thus feel a stronger sense of agency and ownership in the research project. In addition, ethical considerations are not simply about protecting participants and other people they may include in their photos but also about the construction of knowledge. The selection of photographs, and which ones are safe to include, adds an additional layer to how meaning is constructed and who constructs that meaning.

Other challenges inherent in participatory photography include consistency and follow-through with your participants. As with most qualitative research, there are always going to be participants who do not show up for a scheduled interview or who drop out of contact. Participatory photography is no different and therefore it is important to make sure you determine the minimum number of participants you want for your study and recruit more people in case you lose some through attrition.

While losing participants along the way and then not having enough participants can be a challenge, so too can the sheer volume of photographs people make and want to share. With smart phones and digital cameras, participants are able to take huge numbers of images and can find it difficult to limit the number they want to use to tell their stories. If this is the case, it does offer an opportunity for exploring with participants why they have so many images but it is still important to try to put parameters around how many photos you want each participant to take so that you can realistically go through each one in a single interview, realizing that they may not stick to those numbers.

FINDING MEANING INSIDE AND OUTSIDE THE FRAME: INTERPRETING PARTICIPANT-CREATED PHOTOGRAPHS

Photography has a powerful claim to realism. Despite what we now know about photo retouching and editing, we still tell ourselves ‘what you see is what you get,’ especially when the photographs seem to show something as mundane as sheep in a field, the contents of a refrigerator or a parking lot filled with cars. As Ball and Smith write,

photographs of people and things stand as evidence in a way that pure narrative cannot. In many senses, visual information of what the people and their world looks like provides harder and more immediate evidence than the written word; photographs can authenticate a research report in a way that words alone cannot (1992:9).

When a photograph has obviously been edited, with something like a Snapchat filter, we know to interrogate it further and to ask why someone chose that filter. However, when a photograph is not so obviously manipulated, we tend to take it at face value. Photographs serve as hard evidence and as researchers we use them to indicate that our research is authentic and an accurate reflection of reality. However, from a perspective such as this, photographs are not interrogated as data themselves, but rather as factual representations of time, space, and place. It is this unconscious use of photographs that I wish to question here, because our research participants (and as researchers creating photos ourselves) we choose to frame or crop in a particular way (and with easy photo editing apps and filters, we can also dramatically change a photo to reflect a wide array of feelings and perspectives). We choose one photo over another to help us tell our story and we place it in a specific way, in a specific order within the story we recount. As Ball and Smith so cogently remind us, “it is people and not cameras who take pictures…photographs are not unambiguous records of reality: The sense viewers make of them depends upon cultural assumptions, personal knowledge, and the context in which the picture is presented” (18).

Photographs are not direct, “truthful” records of reality and we cannot interpret them as such. They are instead someone’s visual statement about the world they live in and their experience (Worth 1980:20). Images, particularly the photographs we make and share, uncover what is culturally and socially significant for us (Ball and Smith 1992; Worth 1980).

As we view images, it is useful to employ all the empathetic skills we have as ethnographers (and human beings) at our disposal. We must attempt to think about how we read the visual “story” our participants are presenting us with, even as we listen to their telling of it. We can go even further by thinking about how our personal “reading” of these images might be read by others and what that does to the story and the evidence or answers to a particular question it contains. The idea is a bit like Alice going down the rabbit hole, I grant you, but one that applies to all ethnography, I think, for ethnography is only as good as the story teller’s ability to express in words their very personal, visceral experience and the reader’s ability to hear and see that story themselves. However, when I sit down to write a paper or report or create a presentation to share my analysis, it is my construction and my organization of the photographs, so my mark is more firmly and patently on the story that follows than any one of my participants.

Sarah Pink argues that researchers “should attend not only to the internal ‘meanings’ of an image, but also to how the image was produced and how it is made meaningful by its viewers” (2003:186). For my purposes what is most important is to look at how my participants imbue their photos with meaning and, in turn, how those images are further imbued with meaning by my reading of the images and the stories behind their production. Like Sarah Pink, I do not see the written word as the only or as a superior form of ethnographic representation (2007:4). Images hold a very real power on their own, just as the written word does.

One of the major themes in both the participatory photography data collection and traditional ethnographic observation of my research on Salt Spring was the island’s natural beauty. The island is, without a doubt, incredibly beautiful. It is a powerful natural beauty, one that attracts visitors from around the world and seduces people so that they never want to leave. During my conversations with my research participants, as they were telling me their stories of the island through their photographs, natural beauty came up time and time again and in photograph after photograph. Participants constructed a place where beauty was at the foundation of everything. Even while talking about people who seriously struggle to make a living, their descriptions of Salt Spring were still infused with adjectives of beauty and the notion that it is the natural physical beauty of the place that keeps people on the island even when life is difficult. The siren song of Salt Spring’s natural beauty is like the mythical Siren’s song in that it has a dark side as well. It is not simply natural, untouched beauty but its beauty is also a commodity to be consumed and used by locals and visitors alike.

Figure 3. By Dusty. Ruckle Park, 2011. Used with permission.

As Dusty told me, her hand moving to touch her heart and her voice a bit breathless,

It’s just beautiful. It’s just the most beautiful place I’ve ever been. I can have a bad day and then I go for a walk and I’m reminded just how lucky I am to live here. I mean, look at this place. Just look. It’s amazing. People come here and they see, I think the beauty, it, well, it somehow…the nature, it heals people, you know? I’ve lived here 30 … oh, wow, more than 30 years … and I’m still struck by it. It’s part of who we all are here (Dusty, 14 June 2012).

My own field notes, even when describing the challenges of living on a small, isolated island, reference the wild and powerful beauty of the place:

There have been wind warnings for the entire week. Life on an island – sailings get cancelled, people get stranded, either on this island or on Vancouver Island or on the mainland or vice versa because ferries can’t sail because of the wind. Driving home tonight from book club, the power’s out at the north end of the island, just north of the cinema. Giant trees have torn from the ground, taking down power lines in their path to fall across the road and fire trucks are out in force with their lights flashing. They’re the only lights in what is otherwise complete darkness. The moon is new so there is no moonlight to guide you. The powerful wind has actually swept away the clouds that lined the sky earlier, so there’s only starlight to see by, an inky black ceiling covered with a blanket of stars. I had to drive home along a different route one of the firemen directed me to, back along a tiny, narrow bumpy road filled with potholes and bumps from tree roots, slowly navigating my way around branches that fell, wondering if a tree was going to fall on me next. Living on an island teaches you to never underestimate the power of Mother Nature. (Field notes, 24 November 2011, Southey Point)

Dusty and I both were emotionally affected by the beauty of the island—one of the primary attractions glossy travel profiles and tourism advertising highlight—and it forms an essential part of our definitions of Salt Spring. While I was and continue to be aware of the irony in this and my role in reproducing Salt Spring within a dominant discourse, Dusty was not in her reflections of her photographs. For her, as for several other photography participants, the natural beauty of the island was so great that it almost stood outside any possible negative aspects of the island. She went on to describe her personal challenges living on the island with a husband suffering from dementia and how isolating it could feel, but that the natural beauty she woke up to every morning outside her bedroom window acted as a balm and calmed her even on the worst days. I could hear it in her voice, that breathlessness and a sigh as she described it and relaxed a bit more into her chair, drawing solace from the beauty in the photographs she was showing me and then gesturing towards the window, pausing to look outside for a moment before taking a deep breath and moving to the next photo.

The beauty of the island is a given and therefore not something that all but one of my participants questioned. Every single one of them cited the island’s natural beauty as one of the primary drivers for settling on the island. However, only Julia recognized the irony in the seductiveness of the island’s beauty, telling me,

Everybody’s like … Salt Spring’s heaven, well it’s not heaven, really, except in small bits. But when it is heaven, it is, totally…We used to live in Ganges and we overlooked a bit of the harbour and we would see people, walking back and forth to the Harbour House, walking back and forth to the Market and you could always tell, you’d be looking out the window and there’d be a couple, standing by the side of the road, looking at the harbour, and you could just tell what they’re saying, ‘I would love to move here. Look at that view. We could move here. Yes, we could.’ Ohhh, my god, they’re gonna be calling the realtor in five minutes, right? You could just tell. And that’s what this does, right? Sucks you in, oh, it’s beautiful here, it’s beautiful. (Julia, 17 August 2012)

Julia almost resented the beauty of the island and that people used it as an excuse for putting up with things like poorly maintained roads or expensive groceries—all prices to pay for living in such a beautiful place. But at the same time, she loved it and noted that she never tired of seeing sheep in the meadows or hearing tree frogs singing in the spring.

Figure 4. By Julia. Sheep, 2011. Used with permission.

These photographs my participants made of natural beauty, though, are by and large absent one thing—people (see Figures 3, 4, 5, 6). As I saw these photos, I wondered what this absence of evidence, the lack of people in the frame, meant to my participants. I thought to myself that perhaps they were constructing an idea of untouched, “pure” natural beauty free from human impacts. As I spoke with my participants it became clear that it was partly that, but also that they saw natural beauty as a kind of character or personality, anthropomorphized as a female being who takes shape as the island and exists in concert with as well as separate from the people who live there.

Duncan exemplified Julia’s story in that he and his wife, Emma, came to Salt Spring as vacationers and fell in love with the beauty and slower pace of life on the island. He and Emma moved their Internet business to the island and worked very hard over several years to tame their five acres of land so that they could grow as much food as they possibly could, wanting to be as self-sustaining as possible. He showed me photographs of their garden and spoke of how much work it was, “more than we ever could have possibly imagined. It’s like a beast, sometimes, that you can’t turn your back on or you’ll have blackberry vines and broom taking over everything before you know what hit you” (Duncan, 21 September 2012). Despite his descriptions of fighting back nature, he also embraced it, noting that being able to walk along the beach or hike up the mountain every morning was something he had come to cherish and didn’t think he’d be able to ever find anywhere else.

Figure 5. By Duncan. Beach Life, 2012. Used with permission.

When we sat down to look at her photographs, Emma set the stage when she told me,

They say that the island holds onto the people she wants, the ones that need to be here and the others she spits out. If it’s too much of a struggle, then maybe you’re not meant to be here, you know what I mean? It’s not always easy being here. It’s beautiful and the people are lovely but it’s also very hard work. I’ve replanted that apple tree three times until it found a place it was happy. We’ve taken out truckloads of broom, and we’re still fighting it. But I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else now. We’ve got a good life. I know we’re lucky… [laughing] I guess the island wanted us (Emma, 13 June 2012).

Figure 6 is notable for another piece of evidence that we cannot see. Because I knew where my participant, Emma, had taken Figure 6, I also knew that it was framed in such a way that it excluded the pulp mill across the water in the town of Crofton. When I asked Emma about this, she admitted that she had deliberately framed her photo not to include the mill, saying, “it’s so ugly and it’s not part of Salt Spring. It’s like another world over there” (Emma, 13 June 2012). “It’s like Mordor,” her husband Duncan chimed in from across the room, comparing it to J.R.R. Tolkien’s land of evil, death, and horror (Duncan, 13 June 2012). Both Emma and Duncan deliberately removed images of the Crofton pulp mill because it does not fit with their definition of Salt Spring as a place of pristine, natural beauty. When comparing Crofton to Mordor, Duncan then added, after a pause, “It’s not like everything is perfect here. We have our problems, of course, but it’s pretty idyllic a lot of the time. And it truly is one of the most beautiful places in the world” (Duncan, 13 June 2012). Figure 7 shows the Crofton pulp mill from a slightly different angle from Emma’s photo of Vesuvius each, taken when I was crossing on the ferry to Salt Spring. Vesuvius beach is across and to the south from the pulp mill and all of its industrial pollution and ugliness.

Figure 6. By Emma. Vesuvius Beach, 2012. Used with permission.

VALIDITY AND PARTICIPATORY PHOTOGRAPHY

Photographs and video are not truth any more than words are. They are instead someone’s visual statement about the world they live in and their experience (Worth 1980:20). Images, particularly the photographs we make and share, uncover what is culturally and socially significant for us (Ball and Smith 1992:32). As celebrated ethnographic filmmaker David MacDougall notes in an interview about his work,

there is always an ambiguity about the way a film implies something. It suggests, it draws possible connections, it creates reverberations and harmonics. But this is also one of its strengths, because that sort of complexity is also characteristic of much of our social experience. Something with a meaning in one context will have a different meaning in another, but it will nevertheless drag overtones of its other meaning into the new context (Barbash and Taylor 1996:374).

Substitute still photographs for film in MacDougall’s quote and I think we could make the same argument. Participatory photography provides an advantage in this respect because it explicitly acknowledges the role of human observation, interpretation, and construction of meaning through images. What do we do, though, when we know as researchers that our participants are being especially, subjectively human and framing their photos to deliberately leave something out, as Emma did when she deliberately framed her photo not to include the Crofton pulp mill? Can we consider what is outside the frame evidence even though we can’t see it and is that evidence as valid as what is inside the frame? I think the answer to both of those questions is a qualified yes: if we ask our participants to tell us about what is outside the frame and then further delve into why they left it out, then it becomes valid evidence. I had an advantage because I knew that Emma’s picture could have included the pulp mill, but I deliberately asked her about it and why she had excluded it. Excluding something ugly and industrial and clearly unnatural from an image that she was using to describe the natural beauty of the island was equally strong evidence as what she included—I just made sure to document it. How our participants frame their photographs matters. They make deliberate choices about what to include and what not to include and if we gather data through asking them why, evidence outside the frame is valid and equally important as that which is readily apparent. It is our job as researchers, though, to ask about what we don’t see just as much as what we do see and to find out the why behind the image.

Figure 7. The Crofton Pulp Mill, aka Mordor. © 2018 Tabitha Steager.

Ephemeral Evidence, Modification, and Social Media

To further complicate matters around what we see and don’t see, when we begin to think about images posted to social media sites like Snapchat or to Instagram stories, where images are temporary and disposable due to the limited timeframes they exist within these apps, the evidence we may be interrogating is ephemeral and exists only in the short term. It is beyond the scope of this paper to delve more deeply into images and video posted to social media (often after being highly edited through an app’s built-in lenses, filters, and special effects) than a brief discussion here. It is important to mention, though, because it is something researchers using photography (and video) as evidence need to consider. The ephemeral nature of Snapchat and other time-limited social media poses challenges not only for data collection but also analysis—we need to ask what might these temporary, very often highly manipulated images say about the lives and experiences of their makers and what kind of stories people are telling about themselves through these platforms as well as what kinds of evidence the ephemeral nature of the images provide.

Some questions we may ask include: What would a participatory study using Snapchat look like and how might we interrogate the nature of evidence and what is “real” within a platform that is inherently artificial? Further, how does evidence produced in one platform differ from that produced in another and what kind of evidence does the use of one platform over another provide? What might the absence of a particular kind of evidence mean within the frame of specific research questions? When we consider the use of lenses, filters, and editing apps we need to consider conceptions of authenticity and reality and what those look like to our participants. We need to tease out whether someone considers a selfie they modified using an app to soften lines, make their cheekbones and jawline sharper, and slightly increase the size of their eyes and lips an expression of (modified) reality but no less authentic. Or maybe they consider it more authentic because it reflects what they feel is their best self. Perhaps it’s aspirational, expressing what they hope to be. Then there is the contrast of #nofilter and its use, meanings, and value—where could that fit into the equation?

While the type of participant-generated evidence that arises out of social media will likely look vastly different from, say, participant-generated photos that are unedited and more “documentary” in style (like those my participants on Salt Spring made), I think we need to be careful not to place them in a completely distinct realm of their own. When participants create imagery—still photos with #nofilter, heavily edited Instagram images, or Snap photos with cat face lenses placed overtop—it is a reflection of their “truth” and their experiences of the world, no matter how artificial that imagery might appear visually. We cannot say that they are less valid evidence of the reflections of reality as our participants experience, or express, it. As I have discussed, our work as ethnographers is to tease out the very personal, embodied, individual experiences of our participants’ lived experiences and then make sense of them as a whole. We look for shared patterns as well as distinct differences, that little piece of evidence that engenders questions we hadn’t even thought of when we started.

Lived experience today, for many of our research participants, includes day-to-day interactions with their smartphone cameras, often posting the images they create, either unedited or not, onto social media. It is important to pay attention to the differences, of course, between the images generated and whether they’ve been manipulated or not, but what remains at the very core of our interrogation of those images, as with any ethnographic enquiry, is the why: Why did they choose to make that photo when and where they did? What can the evidence contained within the photo tell us as well as what is not included to answer that why? Why did they use a specific filter or not? Why did they choose one photo over another? What does sharing their images with a researcher mean to them and why? These kinds of questions apply even though the types of mediums are increasing and changing at what can feel like record speed. As ethnographers we need to adapt our inquiry to fit, of course, but this is something that ethnographers do particularly well.

CONCLUSION

To return to the beginning, photographs are not factual records any more than words are. They are imbued with context and subliminal and unspoken meanings. When our participants create photographs based on our directions, the sense they make of the photographs as creators, and in turn what we make of them as researchers, is grounded in cultural beliefs, personal experiences, and context—both of where and when the photo was made and where, when, and how we discuss it with our participants. My participants, and my own experiences, taught me that the creation of place is one fraught with conscious and unconscious arguments about who has the right and the power to define a place. The notion of power, and who holds it, is always at the center of any ethnographic enquiry but becomes particularly noticeable when it is research participants themselves who are creating evidence through material they make, such as photographs. When participants create evidence and direct how we as ethnographers are to understand this evidence, the power shifts from the researcher leading the charge to a more equitable partnership that is more reflective of how knowledge is produced. Using participatory photography actively acknowledges that ethnographic evidence is co-created and knowledge is built together with our participants.

Of course, as viewers of these images we construct a story of space and time that will differ from every other viewer; we can’t ever know exactly what someone else is seeing, just like that salmon color my mother and I argued about. When working with participants and the photos they make, it is important to keep this framing in mind—participants recount to us what their photos mean to them, how they went about taking them, and what the process of making the photos means. However, as researchers we cannot help but see those photos in a different way than our participants. We bring additional analysis and interpretation to layer on top of that of our participants, mixing images and text to create ethnographic evidence that we then present to other audiences. For example, Figure 8 is a montage of images I’ve chosen to put together, all photographs of a Salt Spring ferry, three made by my participants and one of them made by me. I include this montage not only because it shows the importance of ferries to people on Salt Spring, but more importantly because it epitomizes participatory photography for me—it tells a story about Salt Spring co-created by my participants and me. I would argue that including their photographs alongside mine helps to lend credibility to my work. I didn’t just make a picture of the ferry and then provide my interpretation of how it contributes to Salt Spring as a place. My research participants also made photos of the same experience, and in showing it to me and discussing it together, we co-created ethnographic evidence. Having participants actively involved in the research process through methods like participatory photography lends our ethnographic work credibility. This paper is an argument for incorporating the method into all of our research projects where images are used, to help to bring our participants’ knowledge and experiences to the forefront, which is where we hope to be in any ethnographic endeavor.

Figure 8. Salt Spring Ferry. Clockwise from top left: Duncan, 2012; Dusty, 2011; Tanya, 2011; Tabitha Steager, 2011. All used with permission.

Tabitha Steager is an anthropologist with interests in place and community, food, visual ways of knowing, and Indigenous rights. She received her PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of British Columbia. She has conducted research in Canada, the United States, Mexico, England, France, Italy, and with First Nations across British Columbia.

NOTES

Thank you to the EPIC reviewers and curators for their instructive, thoughtful comments, especially Rebekah Pak for her insightful comments, all of which helped shape this paper. Please note that the views expressed in this paper do not reflect the official position of Pacific AIDS Network and the content is based solely on my own research, not that done under the auspices of Pacific AIDS Network.

REFERENCES CITED

Ball, Michael S. and Gregory W. H. Smith

1992 Analyzing Visual Data. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Barbash, Ilisa and Lucien Taylor

1996 Reframing Ethnographic Film: A “Conversation” with David MacDougall and Judith MacDougall. American Anthropologist 98(2):371-387.

Bean, Jonathan

2008 Beyond Walking with Video: Co-Creating Representation. In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference [EPIC] 2008, 104-115.

Edwards, Elizabeth Edwards

2015 Anthropology and Photography: A long history of knowledge and affect. Photographies 8(3):235-252.

Faulkner, Susan A. and Alexandra C. Zafiroglu

2010 The Power of Participant-Made Videos: intimacy and engagement with corporate ethnographic video. In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference [EPIC] 2010, 113-121.

Geertz, Clifford

1988 Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Golub, Alex

2017 Bronislaw Malinowski: Don’t Let the Cosplay Fool You. Savage Minds website, May 15. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://savageminds.org/2017/05/15/bronislaw-malinowski-dont-let-the-cosplay-fool-you/

Harper, Douglas

2002 Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation. Visual Studies 17(1):13-26.

Jacknis, Ira

1988 Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali: Their Use of Photography and Film. Cultural Anthropology 3(2):160-177.

MacDougall, David

1997 The Visual in Anthropology. In Rethinking Visual Anthropology, Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy, eds. Pp. 276-295. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Packard, Josh

2008 “I’m gonna show you what it’s really like out here”: the power and limitation of participatory visual methods. Visual Studies 23(1):63-77.

Pink, Sarah

2007 Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research (rev. and expanded 2nd ed.). London: Sage.

2003 Interdisciplinary agendas in visual research: re-situating visual anthropology. Visual Studies 18 (2):179-192.

Worth, Sol

1980 Margaret Mead and the Shift from Visual Anthropology to the Anthropology of Visual Communication. Studies in Visual Communication 6(1):15-22.