Article 2 in the series Data, Design and Civics: Ethnographic Perspectives

The windows were dirty when I arrived on the fifteenth floor of City Hall. I had been hired as the Los Angeles’ Innovation Team’s in-house social communication researcher. My official title was “Design and Data Research Fellow,” although my badge read “intern,” which after 6 years in a PhD program was an unusual change. After a few weeks I got tired of looking through the grime, and trudged upstairs to the shared kitchen to locate a bottle of spray and a few paper towels. The only way to reach each side of the windows was to lean out, because they opened outward. I’m afraid of heights, so dangling halfway out the windows fifteen floors was enough to give me butterflies. Still, the cleaning plan was up to me.

My work considers how people use technologies to improve civic life. I’m especially interested in how individuals become involved in institutional change through and around data. You hear this argument a lot among civic tech advocates: it’s not just about the technology or open data, but the “change” that comes with it. Aaron Snow, Executive Director of the federal government’s in-house consultancy 18F, recently claimed that “18F isn’t really a digital services office, we are a change management office disguised as a digital services office.” Abhi Nemani, the Chief Data Officer who invited me to be a fellow at city hall, wrote, “we want to see them hire, promote or support ‘change agents’ who want to do something differently.”

Snow and Nemani were gesturing to groups like Innovation Teams. Innovation Teams try to change the way government works by altering internal processes, changing local policies, and improving government technologies. Innovation Teams are not new – they have a long history in product design and business management. What is new is the idea that Innovation Teams bring about civic benefits rather than organizational efficiencies.

Innovation Teams in government take many different forms. 18F at the federal level focuses on agile development. Boston’s Office of New Urban Mechanics has a flavor of experimental urbanism. Despite differences, Innovation Teams share a set of core characteristics. They are small teams, often of institutional outsiders. They have creative funding sources, which is appealing to governments that have seen budgets slashed. They also seek to improve the way government functions while using the same components.

The particular type of Innovation Team I was working on was an “iTeam,” a term branded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Nesta. This incarnation of Innovation Teams got traction in the United States through Bloomberg Philanthropies awarding multi-million dollar grants in 2012 and 2015 to bring Innovation Teams to receptive cities. iTeams are tasked by mayors to address “wicked problems” of cities such as homelessness, crime, or housing.

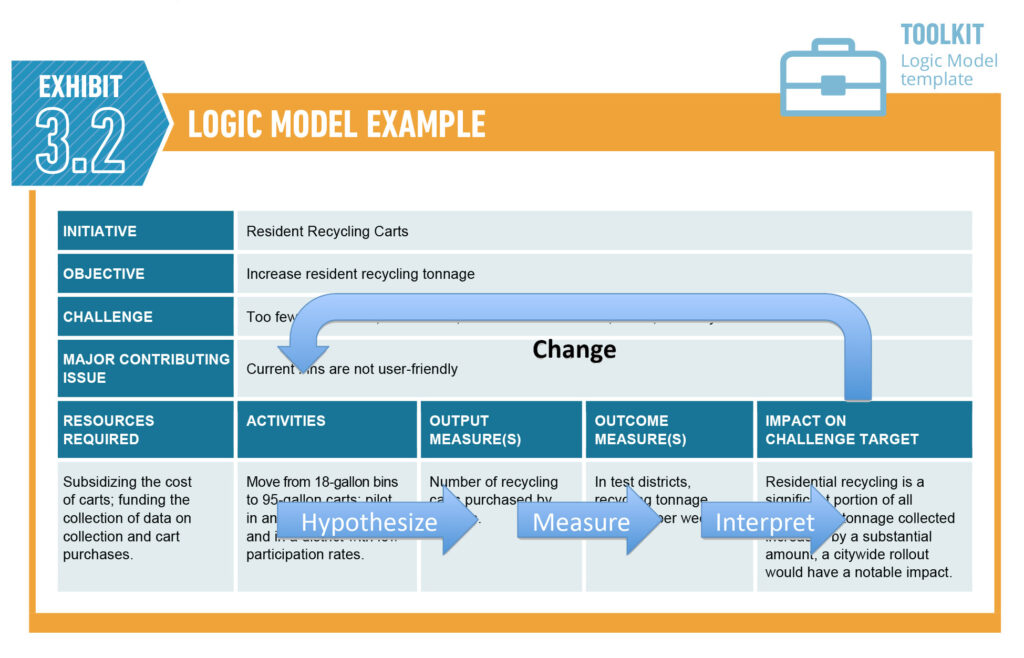

A Logic Model: Example of a Process of Data-Driven Learning (City Hall Innovation Team Playbook, Bloomberg Philanthropies; arrows mine).

Forms are important in the Bloomberg world. Recipes for problem-solving processes are articulated in the playbook, often casually referred to internally as “the purple book.” The Logic Model above is taken from the purple book and is filled out to clarify initiatives. Activities gather data that are connected with outcomes and subsequent impacts, leading to the alteration of activities. Paperwork becomes part of a data-driven cycle that roughly conforms to the American philosophical tradition of pragmatism. In the mold of James, Peirce, and Dewey, team members make knowledge visible to help them understand what it is they are doing and evaluate potential for improvement. Forms also serve to unite stakeholders. The idea of delivery, drawing on Michael Barber, is that stakeholders agree on these plans, take ownership of the initiatives, and implement them. The iTeam then focuses on a new problem for the city as a kind of in-house consultancy that leads by example. Some variation of this idea is present across different types of Innovation Teams.

Although I was not officially tasked as an ethnographer, applying an ethnographic perspective to iTeams revealed another dimension of the work. Julian Orr, in his ethnography of copier technicians Talking about Machines, discussed the importance of creative improvisation to local practices. He found that an oral culture could not be captured by manuals and paperwork. Similarly, in Los Angeles material objects structured communication and “change talk” even as the team creatively maneuvered around them. Nortje Marres has noted how material objects shape communication that occurs around them, enabling participation and bringing public issues to the fore.

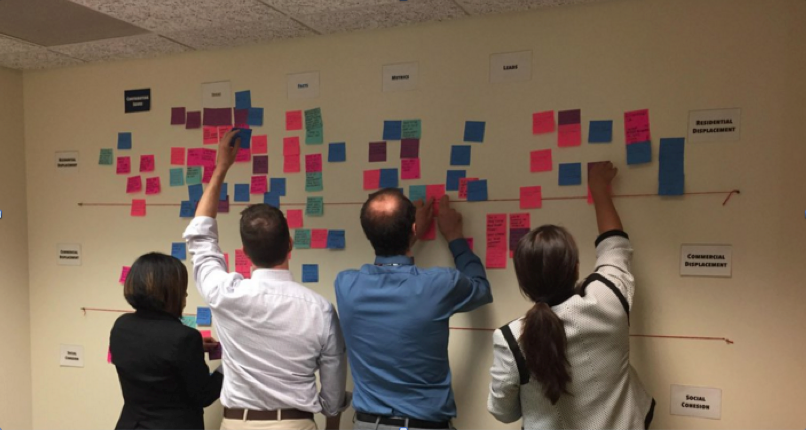

Communication practices often involved site visits, conversations, and the ubiquitous sticky notes to organize thoughts. Eventually these ideas might find their way to an official document and passed up the chain of command. However, forms can’t entirely capture the richness of local practices. Much of the team’s approach was inextricably local and relied on members’ creativity and instincts, rather than data and forms as ways of knowing. Data was still how they gained “insights,” detected change, and guided action. But, true to pragmatism, the team also captured and uncovered data in response to these idea-generating sessions as a cycle of learning. You could not remove the individual from data. It was surprising to me how much the data bore an imprint of the work situations – methodologies, instrumentation, and analysts – that produced it.

The biggest surprise working on an Innovation Team was that the technologies the team was interested in were not radically new. They were often versions of existing technologies that had been proven to work in other situations and locales. Technologies were tied to larger initiatives that had constrained budgets and needed internal and external support. The team needed to garner support quickly, so technologies needed to be familiar. I started to think about these technologies as “mundane innovation” – innovation in the small, reliant on instincts and everyday objects, disentangled from the need to create mythical, perpetually out-of-reach technologies.

What might it mean to approach innovation as strategically mundane rather than exceptional? Critical historian Morozov has claimed that naïve “technologists” are duped by Silicon Valley ideology to apply technology as a quick fix for complex social problems, a phenomena he terms “solutionism.” Yet, processes to construct mundane innovations don’t much resemble what Morozov feared. Although most iTeams have a “data guru,” members are not generally technological experts. The team was, however, sensitized to the community’s needs, institutional constraints, and their own individual instincts. The issue that emerged that was solutionism’s polar opposite. Pragmatism can spin off into cycles of learning and interpreting that never lead to implementation. The forms and deadlines were necessary to move members on to the next step in the process.

Mundane innovation is a slow process of coalition building – a delicate interweaving of the material, social, and discursive that is difficult for organizations to recognize. Orr’s copier technicians found it difficult to put information back into the system, thereby improving it. He pointed to multiple reasons this might be – workers are an oral culture, difficulty in capturing tacit knowledge, and Xerox may not recognize their expertise. The same issues might be at play with iTeams, albeit with much higher stakes. In a ten-year retrospective on the book Orr noted that “society is something to achieve, to nurture; it requires work. This is work the technicians do, it is work the organization does not seem to see, and at times it is work the corporation denies” (p. 1809). Governments nurture and organize society on a grand scale. It too has too long denied work that might result in lasting change. Innovation Teams are becoming an everyday feature of government and a valid occupation for civically minded geeks. Yet, best practices and details about why initiatives succeed or fail are rarely shared. iTeams risk becoming another layer of ineffective middle management – the very thing they are rallying against.

Mundane innovation is unfortunately yoked to the high rhetoric and spectacle of innovation. Mayors need to demonstrate they are helping to solve a range of social problems confronting cities, often outside of what local government has historically tackled. As I type this, Michael Bloomberg has officially announced he would not be running for president. His now defunct campaign ad positioned him as the person to “reform the way government works” because he is “no-nonsense, non-ideological, centrist, [and] results-oriented.” The timing wasn’t right. Always data-driven, Bloomberg cited research showing his running would take votes away from Clinton and virtually ensure a Trump presidency. Still, it’s easy to see how his platform, echoing the radical pragmatism of iTeams, might appeal to a range of conservatives and liberals. Maybe next time around.

Toward the end of my contract I also found myself grappling with a more personal question as a communication scholar: what are the ethical stakes of a communication scholar such as myself working inside public institutions? Communication has grappled with its role in institutional reform over the decades. In the 1940s Lazarsfeld famously explored two traditions – administrative and critical research. Years later, his integrated efforts have long failed. Communication as a discipline is still unfortunately provincial. American social science regards European strands as an entirely different animal. There is still a rift between those who work for the establishment and those who critique it. Lazarsfeld would remind us that asking Innovation Teams to reform the establishment while critiquing it is still a tall order.

Innovation Teams promise a way forward, past these artificial disciplinary barriers, to change government outside of electoral politics. However, their mode of reform has tradeoffs. Bloomberg Philanthropies, as with many progressive-leaning philanthropic organizations, retains the rights to the materials that the team produces, restricting access to the public. This is why none of my work for the team appears in this piece. So as much as I believe in the iTeam’s model of pragmatic learning, I worry the carefully managed communication on the team might exacerbate concerns about iTeams being the latest cadre of government “experts” that operate outside the public eye.

I am proud to have worked with the LA iTeam. They are an amazing and diverse group with ideas to improve civic life in Los Angeles. Hopefully they will announce their work on sustainable neighborhood revitalization soon so the public can better understand the ways their work might benefit the city. Openness and public participation – core concepts in communication – are also what separates a reflexive, pragmatic model of learning from a closed cybernetic one. Visitors regularly commented on the view after I cleaned the windows. What isn’t clear is who cleans them now that I’m gone. It wasn’t explicitly part of any initiative, nor did I make any steps to “deliver” that responsibility to someone else. The challenge of Innovation Teams might not just be to provide solutions that work, but bring the public into conversations with these new teams of reformers. Only then might people look in as easily as employees look out.

Related

Introduction to Data, Design & Civics: Ethnographic Perspectives, Carl DiSalvo

Ethnography of Public Participation, Thomas Lodato

Ethnographies of Future Infrastructures, Laura Forlano

Human-Centered Research in Policymaking, Chelsea Mauldin & Natalia Radywyl

“Hey, the water cooler sent you a joke!”: ‘Smart’, Pervasive and Persuasive Ethnography, Nimmi Rangaswamy et al.

Strategy without Ethnography, Zach Hyman

The Way to Design Ethnography for Public Service: Barriers and Approaches in Japanese Local Government, Kunikazu Amagasa (free article, please sign in)

Service Designing the City, Natalia Radywyl (free article, please sign in)

0 Comments