“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

—Lenin

My country has changed so dramatically in the last few days that I don’t know where to start. I don’t know if I even know my own country anymore. I am reeling. Shocked. Dismayed. Worried. I am not alone in feeling that the UK now faces not one but many existential crises.

The Referendum has delivered a Leave mandate that no political organisation, or individual, is able or willing to enact. The country is in crisis. No one appears to have a plan. And if they did have a plan it would make horrible reading.

I’m not a political pundit and there are plenty of good and intelligent analyses of this slow motion car crash elsewhere. I suggest this piece on the sociology of Brexit, and this and this.

Instead, I want to use EPIC’s invitation to reflect on a related crisis—the interpretive crisis faced by politicians, political parties and those in power who need to radically rethink how they understand the people they purport to serve. It should come as little surprise that I believe the time has come to turn from failed focus groups and oversold analytics to a greater commitment to ethnographic research.

Experts, Elites and the Establishment

Populism is on the rise, that’s obvious. Dissatisfaction with the status quo and those that govern has many sources. Economics prosperity has been trickling up not down. De-industrialisation, austerity, labour market flexibility have created massive job insecurity. Outside of metropolitan areas people have stated they want immigration to stop. They don’t like changes brought about by the free movement of labour.

Many have concluded that politics does not work for them. Populist movements and politics are strong across Europe and in the US. Demagogues roam the political stage.

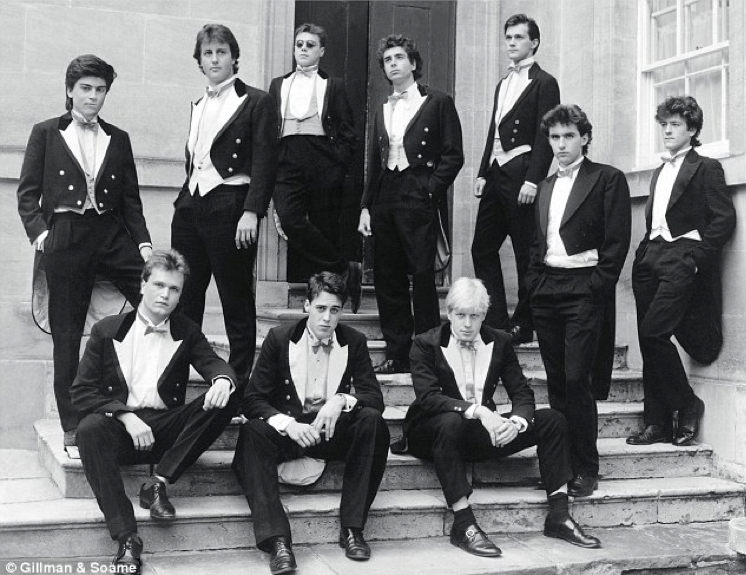

Populism has been a while in the making. It is an easy fire to stoke and often the metropolitan, educated elite have fanned the flames. Last week a prominent Out campaigner—an Eton and Oxford educated son of a peer—could, without irony, talk about how the vote for Out was a vote against elites and the ‘Establishment’. Power in the ruling Conservative party has moved from the man third on the left to the man fourth from the right.

Machine Politics and the Limits of Research

The rise of populism has coincided with politics and political campaigning becoming ever more machine-like and managed. Political campaigning and messaging have become military offensives. Precision targeting of populations means messaging is now designed down to household level.

Big data, while promising message specificity and relevance, has made politics feel less authentic. The sub-text of the political message is now even easier to spot than the text itself.

Polling and focus groups have long been a staple of political positioning and campaigning. New Labour rose to power in the 1990s by using focus groups to get into the heads of their target votes and to finesse their message. In the 1970s and 80s the Conservatives had used focus groups as a way to explore what the polls were saying. As Bill Clinton has said: “There is no one more powerful today than the member of a focus group. If you really want to change things and you want to get listened to, that’s the place to be.”

Focus groups allegedly connect politicians (or their strategists) with real voters and their concerns. But focus groups are not well designed for open-ended discovery. They are better for understanding reaction to ideas and communications. Focus groups are not committed to an emic understanding of the world. They privilege the etic and worse, ignore the emic.

Meanwhile, political polling is in terminal decline. The polls got the 2015 general election wrong. Few pre-Brexit polls got close.

W H Auden’s 1939 poem The Unknown Citizen critiques the standardization of the relationship between citizen and state. He is also questioning the knowability of people through their data.

Our researchers into Public Opinion are content

That he held the proper opinions for the time of year;

When there was peace, he was for peace: when there was war, he went.

He was married and added five children to the population…

Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd:

Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard.

“We should certainly have heard”. Inside the cosmopolitan bubble politicians and journalists did not hear the “howl of discontent with the status quo”. The result was a shock vote to Leave.

Kissing Babies and a Pint of Milk

Politician have contact with the public in constituency meetings, surgeries and other gatherings. They also spend lots of time kissing babies. But time spent in the media bubble or the ‘Westminster village’ mitigates against sustained contact. The closer they get to power the more cocooned and isolated they become. Their knowledge of their constituents’ worlds becomes ever more disembodied.

Occasionally, the media ask politicians the cost of a pint of milk or loaf of bread. Knowledge of these prices is considered a touchstone of their closeness to the world of the electorate. Woe betide those, like David Cameron, who need a crib sheet to answer this question.

That we consider knowledge of the price of milk an effective judge of how in touch a politician remains is worrying. It highlights the poverty of current thinking about how to bridge the worlds of politicians and the polis.

The Brexit vote has confirmed what has long been suspected, or known but ignored. “Rich, mobile people living in our capitals don’t understand the lives of everyone else in society”.

“Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard”

The Brexiters had heard. They tapped into the fears and frustrations of those outside of London (and Scotland). They didn’t offer solutions to the poorer, older and economically dis-enfranchised. But they indicated that they were listening with a powerful slogan ‘Take Back Control’.

Their response was a mix of xenophobic fear mongering, and manifestly falsifiable economic claims. They topped this off with the idea that “we’ve had enough of experts”. Diminishing experts and expertise asserts that you are listening to the ‘man on the street’. Experts deal in facts, but we understand your concerns.

Closing the Gap between Politicians and what Really Matters in the World

I’m not the first to question focus groups and polls in the development of political policy and communications. But I hope I won’t be the last. Political opinion polls are in a death spiral. Anyone with a methdologically informed bone in their body derides the use of focus groups in the world of marketing research.

My suggestion that we put ethnographic research at the heart of developing policy making is not novel either. In the United States the work of the Public Policy Lab and many others has shown what this sort of work makes possible. The UK has a long tradition of using ethnographic research to understand complex social issues. There are even some examples of policy influence. Back in the early 2000s my ethnographic consultancy worked a lot with the think tank Demos. More recently, the UKs Cabinet Office has been doing just that with the Policy Lab.

The Government Digital Service has championed ‘user needs’ above bureaucratic logic.

But to the best of my knowledge no political party has used long-term ethnographic investigation to inform policy development.

This goes far, far beyond knowing the price of a loaf of bread. This is about developing empathy and understanding. It’s about eschewing a liberal, elite perspective on what matters and really grappling with what globalisation, immigration, and the contemporary labour market really feel like. This is about more than taking sound bites out of a focus group and developing ‘the line’ to take in communication. This is about developing policy based on the real world as people experience it.

There’s a lot of soul searching to be done in what’s left of the United Kingdom right now. As you’ll see I’m no political analyst. But in my career to date, ethnographic work has become ever more central to the way businesses understand the world. I don’t see why political parties cannot engage with the world in the same way.

I don’t feel I know much for certain right now. But I do know that we need to build forward looking, progressive post-Brexit policy on more nuanced views of the worlds people live in. Only then can we start to bridge the damaging divide between parties and people. Only then will we be able to start tackling populism.

Related

Human-Centered Research in Policymaking, Chelsea Mauldin & Natalia Radywyl

Simon Roberts, A Profile, Charlotte Hollands

Bring Back the Bodies, Simon Roberts

Models of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Models, Simon Roberts

0 Comments