Case Study—This case study explores a customer experience transformation strategy and development research project run by Deloitte for a multinational U.S.-based home appliance manufacturing company. It explores the shift in strategy and approach for the company based on the team’s digital ethnographic research, as well as applying the ethnographic method to a non-traditional data source (digital and social media). Part one lays out the background on the client and the team and challenge proposed by the client. Part two lays out the details of the team’s methodology and process of evaluating social data using ethnographic and other qualitative and quantitative methods. Part three reflects on the findings of the research and how these differed substantially from the client’s assumptions. Part four evaluates the contribution the digital-based research made in providing a new perspective on the enterprise’s customer experience strategy and understanding of their customers. The evidence from the case study suggests that the value of analyzing the customer lifecycle and customer experience using digital and social media sources provides insight into how people make purchasing decisions, and uncover previously unidentified stakeholders that hold crucial power in the buyer-seller dynamic. The authors’ research methodology provided a new perspective into the decision-making process, influences, and influencers. Their digital ethnographic analysis was effective in providing insights to the client that helped change their view of the customer experience, and helped inform a new approach to engaging and working with their customers, and gave agency back to the customer, as well as provide an urgency for action.

Keywords: digital anthropology, digital ethnography, consumer behavior, customer experience, customer care, CX, customer strategy

INTRODUCTION

A multinational, U.S.-based home appliance manufacturing company had a problem. They were a legacy brand – several legacy brands in fact – that relied primarily on partnering with independent and chain retail stores to sell their consumer appliances across the United States. They also had a young ecommerce store and were looking for ways to expand their online presence to become less reliant on the partner stores. However, despite their legacy and the efforts to shift online, they were losing ground to competitors, both online and in-store.

The company was a quite siloed organization. They hadn’t connected the data or people who touch end consumers, whether that was their own staff, partners, vendors, or others, and had not connected in all the different partners, vendors, internal systems, and other business elements together to get a full view of the customer experience. Customer care was still primarily phone-based, and the team had limited insight into other parts of the company. The client from the IT side of this appliance company had been tasked with addressing these customer experience issues. His charter was primarily focused on lowering costs of the customer care phone center, as well as trying to determine when customers were most likely to call in with complaints or concerns. The client came to Deloitte Consulting LLP with the request that someone should analyze the brand’s customer care experience and help him understand where they should (or should not) engage.

That Deloitte team reached out to the authors, part of a team of researchers within Deloitte, to aid in answering these questions. This research team specializes in digital & social media listening and analysis. As data scientists, design researchers, and digital anthropologists, they take an integrated approach to analyze digital and social media data to understand research challenges from both the quantitative and qualitative perspective.

The project team consisted of the lead author as lead researcher; two other analysts assisting part-time; and the secondary author as the capability lead. Both the client and the internal team were at least slightly skeptical about the value of this social analysis project, but the research team immediately knew that there was infinitely more going on with this situation than just a poor phone customer care experience, and that in order to change the experience, and the client’s mind, they were going to have to provide a detailed, holistic 360 degree view of the people behind these phone calls, behind the decreasing sales numbers, and behind the angry tweets. They were going to demonstrate that digital ethnography could provide insights into and inform the entire lifecycle of the customer and the company.

PART ONE: CHALLENGE AND BACKGROUND

The project was simple yet complex: understand the large-appliance customer engagement lifecycle, and full customer experience from research to purchase to repair.

For the past several years, the Deloitte team had been working with the consumer appliance manufacturing company, and were finally making headway into transforming and updating their customer service and support department, and had started to develop a customer relationship management (CRM) roadmap. Their client, who was based in the IT department, was relatively new to the manufacturing company, and was ready to try something beyond the traditional call-in support the company had been offering for the past 100 years.

While Deloitte team had a strong background in standing up technology and customer service programs, they didn’t have as strong a background in digital and social media service offerings. But they did have something else – a team of digital anthropologists and social media researchers, freshly acquired from an acquisition of a small boutique agency, where the authors and their team had been working with a variety of different clients from different industries.

The Deloitte team reached out and asked the social research team to analyze the “digital voice of the customer” and understand the manufacturing client’s customers’ experience. The Deloitte team was looking for specific insights on client sales and service and high level recommendations to inform their CRM roadmap and strategy development. The team wanted to better understand how to incorporate digital technologies and capabilities into their roadmap.

The research team understood that customer service is not just a call center anymore, that in the age of social media, it involves servicing and engaging with the client across the entire customer journey (Leggett 2014; Palmer et al. 2015; Schoeller 2014; Vaccaro et al. 2016). The social team knew they needed to go one step further and show the client the impact of the disconnect identified in their customer experience chain, and the value of connecting it together in a meaningful way, to elevate their customer experience and help them differentiate as a brand. The manufacturing client truly did not understand just how broken the experience was – so there was a bit of diagnostic work that needed to happen with the research team before the client and Deloitte could implement their massive CRM roadmap.

The social research team was asked to analyze numerous brands for different audiences engaging with or discussing the brand, perceptions of the brands, and customer service pain points, and determine the best approaches the manufacturing client could take to improve their customers’ experience. They decided to look more broadly, beyond just customer service interactions, the entire customer journey, soup to nuts, to understand what expectations customers had, what was really happening on the ground, and how the customers responded.

PART TWO: METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH

Methodology

Digital anthropology is defined a number of different ways. It was traditionally thought of very narrowly, merely an ethnography of an online community, or used as a methodology that accentuates “traditional” anthropology (Boellstorff 2012; Russ 2005).

“Ethnographies of online communities and cultures are informing us about how these formations affect notions of self, how they express the postmodern condition, and how they simultaneously liberate and constrain.” (Kozinets 2010:36)

“[Digital anthropology] reveals the mediated and framed nature of the nondigital world.” (Miller & Horst 2012:18)

However some of these definitions miss the two-pronged implications of digital anthropology – it is both capturing a specific culture and cultural experience with its own rules and standards and behaviors, while also studying HOW people are using new technologies to communicate with their own offline cultures and communicate. Finally, many analysts are also using digital technologies to collect and analyze the data, which can impact both the volume of data that can and rightly should be analyzed, but can also impact how the analyst comprehends the data set, since like all data collection the questions and data collection are both influenced and biased by the researcher themselves.

Pink et al. (2016) explains digital ethnography:

“…takes as its starting point the idea that digital media and technologies are part of the everyday and more spectacular worlds that people inhabit… In effect, we are interested in how the digital has become part of the material, sensory, and social worlds we inhabit, and what the implications are for the ethnographic research practice.” (Pink et al. 2016:7)

For a simpler, more applicable definition, Jennifer has often described it as: “using an unstructured, often unfiltered medium (user generated digital content) that allows you to observe behaviors with limited interference from the researcher.”

Social media listening is often thought of as a research approach generally focused on producing statistical or purely quantitative data to qualify what is occurring. Digital anthropology has a primarily different focus of understanding people and behaviors. By analyzing “social listening” data through an ethnographic lens, analysts are typically able to understand people in their digital context, and provide answers to deeper questions about how different people do something, and often the motivation behind it.

For this particular project, the social team applied digital anthropology by looking beyond the culture of one sub-group or a specific topic, and instead looking at how multiple different sub-cultures view and relate to a brand, topic, or challenge. Social media analysis has traditionally been used in a corporate setting for understanding how to market products better and how to key into the right messaging. Through their own independent research, the social team determined that the data could also be used not just to understand how people were engaging with a brand, but the different kinds of audiences engaging with a brand, and how different Internet sub-groups related to each other and to larger topics – from wine preferences to dishwasher purchases (Hammond 2008; Kelley 2011; Palmer et al. 2015).

They have also been able to understand how these different groups interact with the offline world. As the offline worlds and online worlds have become more merged, individuals will often tweet at companies about a bad in-store experiences, ask their peers questions about a product they are looking at in a store, ask for recommendations, discuss eco-friendly options, the right color, and share their excitement at discovering the “perfect fit,” and essentially track their entire customer journey online. This is not necessarily always done by one individual, but through the amalgamation of tweets, blog posts, forum questions, and public Facebook rants, analysts generally are able to sociologically piece together an entire customer journey, including how their experiences color other audiences’ view of a brand, store, or topic. (Palmer et al. 2015; Vaccaro et al. 2016).

Both ethnographic market research and social media analytics typically begin with a question from the client. A traditional market researcher might start by writing up a survey and then screening potential study participants by asking them a series of qualifying questions. Once the participants are selected, the analyst interviews the participants alone or in a group. The analyst asks participants a series of questions to uncover their purchase decision-making processes, consumption habits, lifestyle, and influences. The research analyst might even accompany them to the gym or a retail store, or present them with competitor products for their feedback. These qualitative findings are then crafted into a quantitative survey to measure the results.

For social research, an analyst might begin by dividing research questions into relevant keyword queries and then inputs these as searches into social listening tools. These tools crawl millions of posts and bring back publicly available information from blogs, forums, and other social sites. The social media analyst then analyzes these posts, organizes the data, looks for patterns, and pulls out the key conversation themes, major audience groups, and other salient insights. While social media analysis is more quantitatively based, it still requires an analyst to look at qualitative conversational data and add meaning. Analysts may not be able to follow the individuals in a target audience throughout their day, but they can follow their routines through posts on social media, as well as all their friends and how they engage with each other online. (Kelley 2015)

Project Approach

Analysts began by creating Boolean queries for each of the different brands, sub-brands and competitor brands the client was interested in comparing. They then added custom excludes for inappropriate and non-relevant conversations for each Boolean query, but overall attempted to maintain the same keywords, verbiage, and conversational style that is common among consumers, vs. professional financial bloggers, news reports, or other communication styles. For example, the company might use the model number of a washer, while a consumer would describe it by its features, “the red washer with extra space and lid on top.” People may also use shortened versions of names or terms, like MIL for “mother-in-law” or call an accessory dwelling a “MIL Pod”. Excludes could also be used to differentiate between “waterfall model” in web design instead of garden landscaping.

The analysts then entered the Boolean queries into a third-party social scraping tool, filtering by Global English, scraping any mentions from the previous 12 months. In a matter of four minutes, the tool collected approximately 2.1 million social media conversations, with 650,000 direct mentions of the brand and its main subsidiary brands. The remaining volume consisted of competitor brands the client was interested in comparing themselves to. Figure 1 shows some of the sample content collected.

Figure 1. Sample posts from the team’s collection of social data around the appliance manufacturer and its competitors. Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Once the data was collected, the analysts reviewed the data to discover conversation themes, perceptions, and underlying audiences discussing these brands in social media. They analyzed posts to discover conversation themes, perceptions, and underlying audiences discussing these brands in social media. The lead analyst also looked at self-reported demographic data captured with the relevant digital content to understand the gender, age, and location of relevant audiences.

The team then used qualitative and quantitative analysis to identify key themes that occurred within the data relevant to the research question, key audiences engaging in the conversation, top sites where the manufacturing company and its competitors were discussed, and perceptions about the experience of engaging with the client at all stages of the customer journey. They also looked at key themes and perceptions around key competitors, but not to the same depth.

PART THREE: RESULTS – UNEXPECTED INSIGHTS FOR THE CLIENT

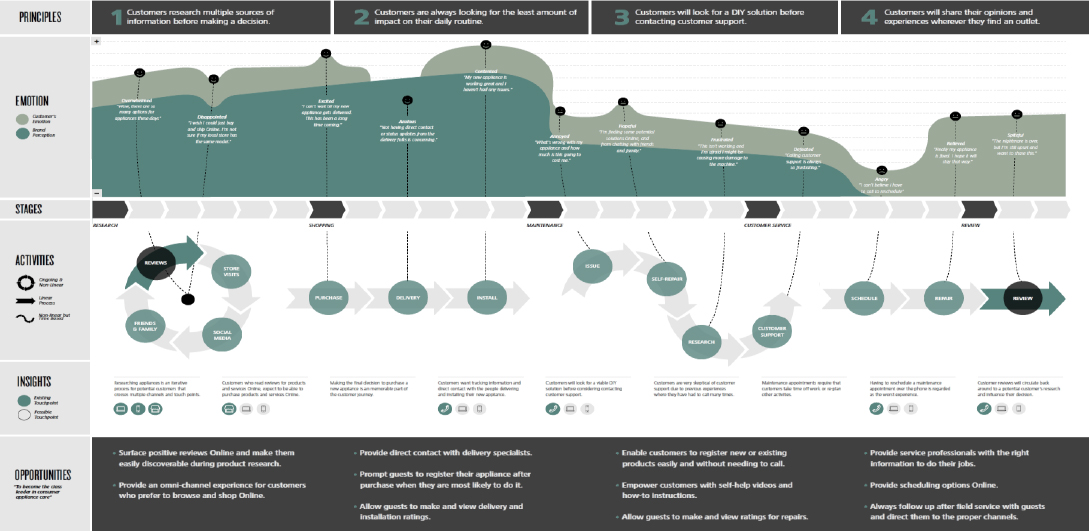

The research team was able to demonstrate that the customer experience was more of a lifecycle than a journey. This journey played out in two ways:

- Because the brand was a generational investment (what your parents bought you were more inclined to buy), customers returned to the same brand over and over, until their allegiance was tarnished or destroyed by bad customer service or other bad experience.

- What one customer wrote online fed into another shopper’s perception and evaluation of the brand when they were looking for a new appliance, including ease of engagement with customer service, longevity of the appliance, ease of repair or access to repair person.

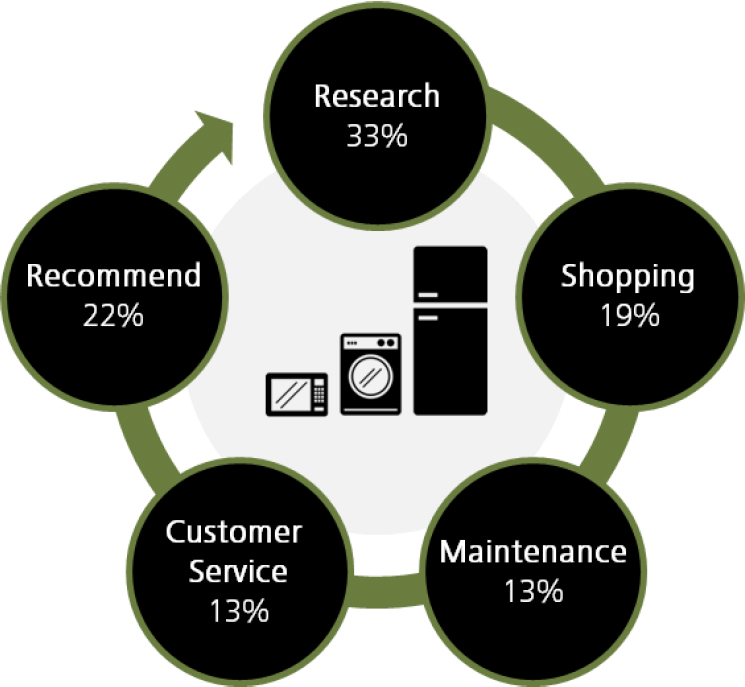

Figure 2. Visualization of the phases of engagement a customer had with the brand, or the “Engagement Lifecycle,” and the percentage of conversation that fell into each phase of the engagement experience. Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

The lifecycle could be divided into the following stages, as also illustrated by Figure 2:

- Research: People did their pre-purchase legwork by asking for advice on Twitter and reviewing blogs. They attempted to narrow their options before making final purchase decisions based on quality, reliability, and price.

- Shopping: Consumers expressed a preference towards buying from a brick and mortar store, and valued an informed staff. When shoppers got to the store the field had already been whittled to a couple of brands based on features, but the final decision was influenced by price and product availability.

- Maintenance: People were reluctant to call a repair person because of presumed cost and the perception that their problem wouldn’t get fixed. Many often turned to forums and YouTube for DIY solutions. People wanted their appliances to last, but they were not keen on calling a repair person, and would attempt repairs based on information they find online.

- Customer Service: Consumers ranted on Twitter and in forums about the lack of knowledgeable staff at larger retailers and on the phone.

- Recommend: People were happy to share their positive and negative experience with others across their social networks.

Audience – The team identified that men weighed in heavily on a purchase decision, and also were the ones that dealt with appliance maintenance. Men would often go online to attempt to determine from their peers if the appliance was worth repairing or if it was better to buy a new one. This was a complete contrast to what the client had been told by their prior marketing agency.

Not only were men critical in the purchase-making decision, they also broke out into three key audience types:

- Outdoor & Sports Enthusiasts, who were most interested in durable machines that will match their active lifestyles. These audiences discussed multiple outdoor hobbies like camping, hunting, gardening and other outdoor interests that required a lot of cleaning clothes after the activities. This audience also discussed RV’s and second homes that required specialized appliances. “Made in America” branding was important to this group. This group also had extra income to spend on specialized appliances and relatively expensive hobbies, and were willing to spend more if it meant less hassle in the long run. This group also appreciated a hands-on customer service experience. This group included men and women in relatively close volumes, but men had the slight edge in strength of voice.

- Technology Fans, who discussed new capabilities or electronic errors on appliances. They were interested in the latest appliances coming on to the market, and preferably those they could communicate with using their phone or other mobile device. Korean brands were winning the “tech wars” with this audience, but this audience also lamented about how hard it could be to get replacement parts for these appliances. They were also asking for tips on easy replacements, DIY fixes, and other recommendations. This group was dominated by men.

- DIYers, who were trying to fix their appliances, or determine whether it was time to replace it, ranging from easy fixes to electrician-level work. This group was especially eager to offer their favorite tips and tricks for repair, as well as their experiences on appliances with high durability and longevity. They were also open to receiving help and suggestions from branded customer services representatives regarding whether or not something really is worth fixing or better to get replaced. This group was also dominated by men.

- Women made up the majority of the rest of the audience groups, with the demographics that the client was expecting: stay-at-home moms, cooking enthusiasts who were looking to upgrade or replace their kitchen appliances, and young couples making their first purchases for their new home or apartment, usually driven by the female partner.

These audiences shared tips with each other, but in many instances existed online on different forums and social circles, and therefore did not engage with each other.

Multi-generational loyalty to the brand was expressed by customers. Consumers were very dedicated to appliance brands that worked before, or if it was a brand that their parents had had good experiences with.

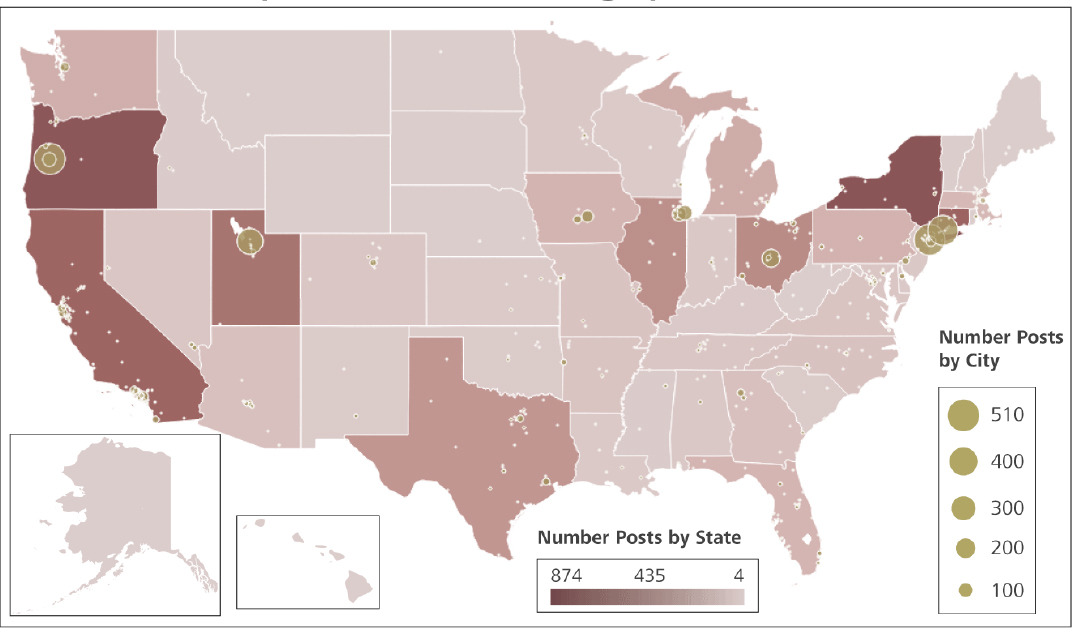

The team also analyzed the volume of mentions of the main brand grouped by major cities across the United States, in part to see if there was regional popularity or concentration based on volume (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Brand-Relevant Conversation by Geographic Distribution For The United States. The research team entered the geographic data collected into Tableau to create a map of where conversations mentioning the brand were located. Conversations were centered in major metropolitan areas, but spread evenly across the United States relative to each state’s population.

Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Analysis by Phase

Research – As seen in Figure 2, customers spent approximately 55% of their discussion about the brand in the research and recommendation phases. In this largest segment of the conversation across all social channels, customers said they were looking for the optimal product that fits their budget and soliciting recommendations from the online crowd.

This was not something the client had even considered; they had been mostly focused on engaging in the customer service phase of the engagement lifecycle. While that was important and valuable, especially since that was the phase where they lost most people, these insights about the Research phase provided them a chance to reach out to shoppers before they had even made a purchase, or respond to incorrect recommendations before they could influence other shoppers.

Shopping & Purchase – Longevity, and durability were consumers’ strongest considerations when making purchasing decisions. Across the entire lifecycle, 23% of conversation was focused on quality, durability, and reliability.

Consumers were doing copious research online before making a purchase. Peer reviews and recommendations were impacting purchase decisions. However, most consumers made their purchase decision based on price or availability of appliances in-store rather than online. Consumer reviews on sites like Yelp, Amazon, and partner store forums were very influential to shoppers during the early research phases. That said, most still liked to view the appliances in store before making their final decision. Even if consumers could get a better price online, they liked to be able to try out the knobs and dials, or “kick the tires” so to speak, and compare brands side-by-side, to get an overall “sense” of the appliance. This concept of “web-rooming” has been identified by others as well (Palmer et al. 2015; Reid et al. 2016).

Customers also found it was easier to ask for discounts or price matches in-store. The final “gut” decisions made between brands were often based on price matching or in-store sales or promotions. In-store availability of features, color, etc., or realizing the appliance’s measurements were wrong for the intended space also played a big part in final purchase decisions.

Consumers were making final purchase decisions in-store and valued a helpful and informative customer service experience in the partner stores that sold the appliances. However, these third-party partners had a lack of understanding of the products’ features. Negative feedback from customers focused on a perceived lack of knowledgeable staff, either at larger retailers or company customer service phone representatives; as well as promotions or discounts not being honored. Customer support staff working in the store or on the phone didn’t know to recommend additional accessories like hose grips or cords, how to measure extra space for appliances, and other considerations.

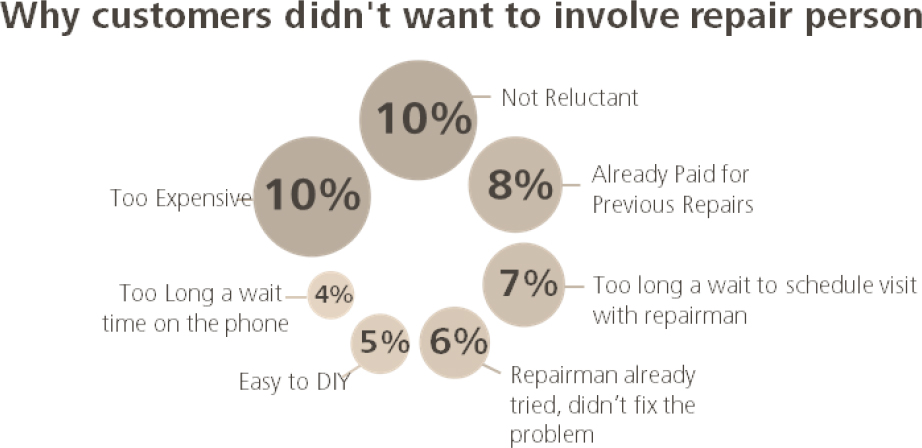

Maintenance – Another huge blind spot for the client was the customer experience around maintenance and repair services. Repairs were usually completed by third parties contracted through a vendor. The social research team discovered that customers actively avoided engaging with customer service agents and repair people.

Repair and maintenance was where the customer service relationship most often broke down. Most consumers expressed having a great experience right up until they contacted the large partner store or branded customer service line for assistance in repairing or replacing an appliance, and then the experience tended to turn negative.

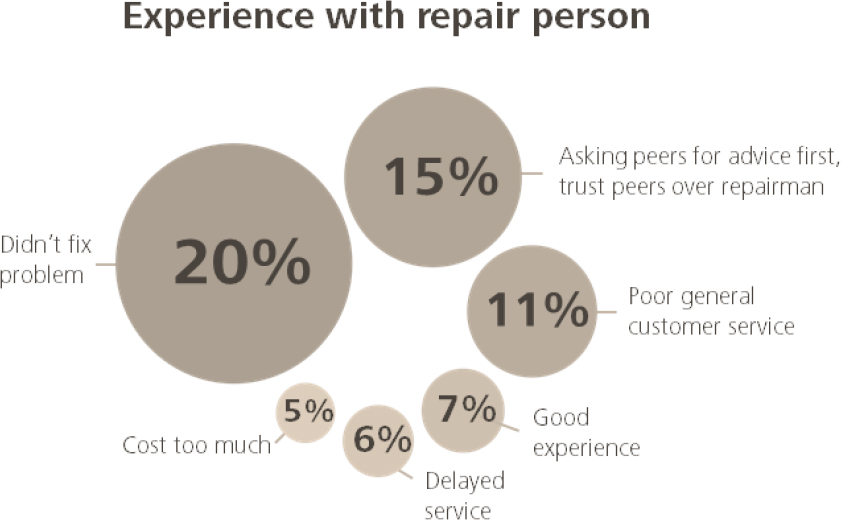

Figure 4. Analysts tagged the content for conversations discussing “repair”. They then coded each conversation for the reasons why customers chose not to engage with or contact a repair person. Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Figure 5. Analysts tagged the content for conversations discussing “repair”. They then identified and coded conversations where customers did engage with repair personnel, whether for a quote or a full repair service, and the experience they had with the repair individual. Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Customer Service – This lack of knowledge continued beyond the in-store experience. The phone experience was usually deemed the most frustrating by customers compared to in-store or social/email engagement. Customers often felt like it was easier for phone agents to pass blame or let bureaucracy get in the way of good customer service. In fact, the perception of the appliance brand was most negative around poor customer service experiences with branded representatives. Figures 4 and 5 show the different pain points customers described when dealing with repairing an appliance and the repair service people, with corresponding volumes of frequency.

Recommend – Consumers discussed their customer service experiences on multiple channels, including experiences via phone, in-store, or via social like Twitter or IM with online customer service agents. This publicly available data of customer service conversations was then evaluated and taken into consideration by other consumers when making purchasing decisions, thus feeding back into the cycle of customer experience. This meant that the company had to also be responsive to the consumer reviews and post-consumer feedback, not just during the pre-sales process.

PART FOUR: CONCLUSIONS AND ASSESSMENT

Outcomes of the Research: Shifts in Perspective from the Client & How These Were Applied

The team delivered the report to the internal team, and was invited to the client site to present the research to both the internal team and the client at the same time. When the presentation team arrived, they had been prepared to present first thing in the morning. However the client kept delaying and delaying the presentation. Finally, after two reschedules and two hours before the team needed to head back to the airport, the client sat down to hear them out.

The client was floored by their report. He had no awareness of some of these pain points their customers were experiencing, especially around the experience with repair persons and the struggle to decide whether to repair or replace. He was also taken off guard by the amount of men weighing in on the purchasing and maintenance decision-making process; they had previously only been tagging women demographics in their online ads and digital content. It had not even occurred to the client to focus on the research and recommendation phases of the customer experience.

The Deloitte team was also floored by the insights the research team uncovered. They had assumed the research team would provide basic recommendations for mobile apps or social media best practices, which Jennifer and Beth did provide as part of their recommendations; but the overall depth and breadth into the kind of insights the research team could pull from social media was fairly staggering to them. In fact, while the authors were presenting the research to the client and the internal Deloitte team, one of the internal team members (politely) challenged the study’s findings, asking about sample size and robustness of the methodology. The authors were able to refer to the 1,000’s of posts analyzed per each specific phase and or topic, and explain the methodology in more detail, at which point he became all the more enthusiastic about the approach and the findings.

As part of the project, the research team proposed several recommendations or solutions to solve many of the key issues they saw emerging for the client, both from a digital engagement perspective but also from a holistic customer experience. Some of the recommendations provided for the manufacturing client included:

- Drive potential customers to segment-relevant consumer education and peer review content with segment specific advertising on popular social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

- Consider engaging the DIY audience segment by launching an Advocates Program that delivers tools, information, and incentive to provide helpful, brand-relevant support to customers.

- Design a program to facilitate easy and up-to-date digital tools and information about the brand’s numerous products.

- Develop internal tools and resources to facilitate easy and immediate access to and exchange of information for customer service representatives to provide seamless cross-platform customer support.

- Develop an online space calculator for consumers to check an appliance’s fit in a certain space. This calculator could take into account the need of extra space for connecting tubes, plugs, and door swing.

- Finally, they could leverage the effectiveness of peer recommendations by identifying loyal, vocal customers and amplifying their stories, reviews, and experiences.

Outcomes

The social research team helped inform the creation of a world-class customer experience and engagement program with the client that made neutral customers into happy lifelong customers. The team informed the client’s product roadmap, including recommendations on consumer education, brand reputation and amplification, partner experience, and involving expert advocate. They also demonstrated how to streamline cross-channel engagement, and hybridize the in-store and online experience to create a holistic experience that drives brand loyalty. The Deloitte team used the team’s data findings and recommendations to adjust their customer experience roadmap to create a more holistic integrated experience for customers engaging with the brand.

The team followed up this research with several customer journey roadmaps for the client to understand how customers who went the “Hire a repair person” path, “DIY” path, and “Replace” path all differed from each other; see Figure 6 below.

The brand was able to re-engage with their third party sales partners to ensure they had easy-to-digest information to share with their customers about why this family of brands was better and more reliable than the competition.

The internal Deloitte team did a project to integrate the client’s CRM across their different groups (service, call center, partners, etc.). A connected application development team started to work on a mobile experience to enable service reps for repairs and other customer services to come to each call with all the information they needed to be informed of prior conversations (digital or offline), complaints, history of what they thought was broken, etc.

Figure 6. Customer Journey Map and recommended features for engaging with a customer following the “repair path” across the entire customer journey. Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Analysis

As with any methodology there are benefits and pitfalls to the approach. The authors have tried to balance the benefits against the pitfalls.

Benefits of the methodology – Overall this methodology is effective in its diversity and real world applications. The data collected using the methodology can easily connect clients with their audience by providing them with actionable insight into their customers’ world, behaviors and passions. It can also quickly integrate customer insights to paint a complete picture of their audience, conversation, and the world their customers live in. The public views and “real-world testing” done by consumers can help inspire innovation to build and deliver the right products and services in the moments that matter.

Researchers were able to reframe several different groups of peoples’ understanding by using digital anthropology methods. Anthropology has been used repeatedly to reframe how people understood the cultures, beliefs and people of other worlds. Using digital anthropology, and specifically social media data in this way, is an update to the methodology, but a continuation to the value of the approach.

One benefit of this methodology is its speed; the team was able to conduct this analysis of numerous brands and consumer groups in just 6 weeks; traditional market analyses similar to these often can take 6 months or longer. Traditionally identifying and setting up interviews with informants can be painstaking, time-consuming, and result in smaller sample sizes. In contrast, “social media analytics can collect millions of comments, posts, tweets, or likes about a particular product or brand, discussed over a few weeks or a few years in a relatively short time.” (Kelley 2015) It can also mean the difference between whether or not a project is viable. (Farris 2005; Poynter 2010)

The speed at which analysts can explore multiple brands is not only generally efficient in cost and times, it can allow these analysts to provide broader comparisons between brands, products, or topics. For example, hard core gamers may be complaining about a particular video game, but is that a problem with just this game, or is this a common complaint among most games of this genre and an opportunity to jump ahead of the competition; or does this audience merely like to complain about this brand and all of its related products? All of these are valuable insights for a company trying to plan their next move, or for an anthropologist to understand their subject better.

Another potential benefit to this methodology is the fact that the data is already digitized, meaning it can be scraped, processed, and categorized by a third-party tool that quickly takes data from forums, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media data and formats them into a relatively easy to analyze Excel file. Traditional methods of collecting data like interviews, video ethnography, focus groups, and even surveys with any open-ended component typically require hours of follow-up note taking, processing, tagging, and curating before it is ready to be analyzed. The analysts who worked on this project still had to do weeks’ worth of reading, tagging, cross-tab analysis, and other data analyses, but saved several more weeks through the collection and digital processing of the social media data.

Social media is also a global phenomenon – there are an estimated 3.7 billion people who have access to the Internet (Real Time Statistics Project 2017), or approximately half of the world’s population. This means that analysts are able to research any topic being discussed anywhere in the world. One estimate says 50% of the Worldwide Web’s websites are written in English, giving an advantage to English-speaking analysts, but there are also 10’s of thousands of websites and millions of conversations in numerous languages (ITU 2015), and the only limitation to studying these topics and conversations isn’t distance or time, it is merely the number of languages the analyst speaks.

Researchers are also able to analyze data over an extended period of time almost instantly, looking at shifts in perception or rise and fall in popularity and tone over the course of several months or years:

“Because of this breadth and speed, social media analysis is also effective at spotting trends that are happening in multiple small pockets around the world, trends that would take months to identify using traditional focus group methods.” (Kelley 2015)

Another strength of social media data analysis is the ability to discover what people want to share with their friends and associate themselves with online. People “like” brands, share topics that are important to them, from technology to social issues to recipes, and ask for guidance from their virtual peers. This kind of data can also be used to identify influencers who persuade and influence others, on their decision-making process, from purchases to which school they will attend next year.

Pitfalls of the Methodology – Of course there are limits to this kind of approach. One aspect that is often overlooked when attempting to collect digital conversations is the bias that comes from the researcher themselves, i.e. viewing the problem from their perspective versus the perspective of the audience. Often when creating Boolean queries to collect data, analysts or marketers will write the keywords that they care about, or how they want the audiences to be discussing the brand. This kind of framing obviously biases the data, and is also not being sympathetic in understanding the context, perspectives, and audiences that they are analyzing. Part of the strength and handicap of this approach is the need to already understand, or quickly become acquainted with, how consumers discuss topics online; how do they discuss a topic? Do they use shorthand to talk about certain things, for example “MIL” instead of “Mother-in-Law”? Some of this is a chicken-and-egg challenge – how does the researcher understand the subject until they research them – but it is crucial to do at least a little bit of preliminary analysis on the audience to understand how they interact and engage online. One common solution is to become a specialist on one or two complimentary industries; some of Jennifer and Beth’s team have deep knowledge on financial conversations or chronic disease conversations online, and are able to quickly create or repurpose Boolean queries for specific research questions and/or projects.

Another potential weakness of this methodology is that it does not always allow for acute participant screening. With traditional methods the researcher typically already knows a good amount about the participant, including age, sex, marital status, income, profession, location & residence, extracurricular activities, and other details. This typically allows the analyst to better understand how a product fits into the participant’s lifestyle or compare two different user groups. With social media data, even with groups that self-select to belong to gardening or parenting forums, they will not always divulge their demographic information, and often with some communities intentionally mask their offline identity and/or take on a whole new identity and persona.

As the authors discussed in a Deloitte Digital blog post:

“Social media analytics isn’t able to reliably provide demographic details for every post or mention that traditional business or industry ethnographers may be used to. This kind of knowledge is typically available to us only if self-reported by the user. Demographic metrics such as gender, age, and location are often shared, but because people withhold their personal information, offer up misinformation, or fail to keep information current, there isn’t usually as much of this type of information and can be misleading. A blogger who is listed as a single, 25-year-old vegan chef could now be a 28-year-old stay-at-home-mom who forgot to update her bio information; a lifestyle change which undoubtedly would influence her opinions and product purchases.” (Kelley 2015)

Social media listening also cannot capture direct perspectives from people who do not frequent public-facing social media channels, whether it is older individuals, individuals in rural areas (both in and outside of developed countries) who have limited Internet access, people who do not speak English or other common language used on the Internet, or finally individuals who are simply not interested in sharing their personal stories and views online. Yet, as people become more comfortable with sharing their lives online, they are sharing more and more personal and demographic information about themselves that can be collected and analyzed (Hammond et al. 2008; Kelley 2011). Individuals will also advocate for and discuss members of their family and friends who may not be active online – caretakers and grandkids on behalf of older individuals, or spouses or parents discussing their partners and or children.

Opportunities for Improvement & Development

Because the team was brought in midstream of the project, they were not as fully immersed with the client team and client’s goals as is ideal. This meant they essentially had to do the research in a bit of a black hole and then shoe-horn their research into the broader consulting project after the fact. This is not a terribly uncommon event in corporate research, with client teams realizing once a project is kicked off that they need more data on a topic. That said, it does indicate that more education may need to be done by researchers working in a corporate environment to reach out to teams and let them know why they need to do research before the project starts. Conversely, managers might need to be open to investing those kinds of funds in their projects, so they don’t create a campaign or other deliverable that totally misses the mark.

Another challenge is education of the research process, i.e. helping both clients and internal groups understand what exactly social media analysis is, and how the research team applies ethnographic methodologies to social media data. People often think of social media as simply one or two channels – namely Twitter or Facebook. They also assume the social analysts are simply looking at volumetric data like the number of likes or shares, or web analytics, or that they are simply Googling topics. The team is still introduced as the “social metrics” group by some internal managers.

More broadly, it is clear traditional market and social media research should not be thought of as either/or options, but instead viewed as complementary research methods. A wide variety of methods can be used in conjunction with one another. Deloitte Digital’s social analytics team has used focus groups and survey data in tandem with social data to look at a question in different ways. They have also informed user experience research with their social media analysis.

Like most tools, the specific project, goals, and research questions determine which method is a better fit. Focus groups and traditional market research may be better for collecting answers to very specific questions for very specific demographics, as well as offering in-depth purchase decision-making criteria. In contrast, social media data analysis may be better at understanding broader trends and perceptions, and how they shift over time, uncovering general themes and perceptions, spotting trends, and locating category influencers.

Summary & Takeaways

The client came to the authors to help “fix” their customer experience, probably expecting to receive generic recommendations for app development and CRM strategies. Instead, the authors completed a thorough analysis of the digital ecosystem of consumer appliance manufacturers across all competitors, to understand the customer experience with all appliances. They then dove into the specific client experience to understand the customer experience.

The research team identified a lifecycle of customer engagement, starting with customers asking for and receiving recommendations, providing feedback across the purchase and repair phases of owning the product, and finally feeding more recommendations and feedback into the loop of customer experience and data out on the public web. The team identified that men played a huge role in the purchase-making decision and maintenance of an appliance, something the client had not considered before. They also identified key pain points for the client that were easily remedied through pre-emptive measures like customer education, rather than waiting for the customer to get mad.

This research helped steer the company away from making the same mistakes they had been making for decades, and allow it to live up to its “legacy” of being a truly family-focused, multi-generational brand. The research team informed the development of the CRM framework and roadmap and propose new developments for the digital ecosystem of customer experience tools and offerings, including a third-party mobile app and social chat capabilities. They also started to work on a mobile experience to enable service reps for repairs and other customer services to come to each call with all the information they needed to be informed. They were also able to re-engage with their third party sales partners to ensure they had easy-to-digest information to share with their customers.

This project was a good demonstration of how the methodology and the data both have some limitations, however is true of all approaches and data sets. More positively, the project also demonstrated that social media analysis can be used to determine and uncover an incredibly wide range of research questions and help determine and prioritize the most useful next steps.

Beth Kelley is a research manager of social insights for Doblin, part of Deloitte Consulting LLP. She has over a decade of experience blending digital and traditional methodologies to analyze human behavior, looking at B2B and B2C engagements, with a personal passion for studying play and enriching environments. markelley@deloitte.com

Jennifer Buchanan is the director of digital insights for Doblin, part of Deloitte Consulting LLP. She has built social listening & research programs at several different companies. She has worked with clients internationally to develop audience insights and strategies for multiple industries. jenbuchanan@deloitte.com

NOTES

1. The names of the manufacturing client and individual personnel, except for the research team, have been obscured or changed to maintain anonymity of the corporation.

2. This research was conducted by and is therefore subject to the copyright of Deloitte Consulting LLP, and all of its subsidiaries including but not limited to Deloitte Digital and Doblin.

Copyright and Permissions

As used in this document, “Deloitte” means Deloitte Consulting LLP, a subsidiary of Deloitte LLP. Please see http://www.deloite.com/us/about for a detailed description of our legal structure. Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting.

This publication contains general information only and Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication.

Copyright © 2017 Deloitte Development LLC.

REFERENCES CITED

Bernard, Russ.

2005 Research Methods In Anthropology: Qualitative And Quantitative. Altamira Press.

Farris, Paul W. et al.

2010 Marketing metrics, 2nd ed. (Pearson FT Press).

Hammond, Joyce, Margaret (Beth) Kelley & Jeffrey Jenkins

2008 “Collaborating and Connecting Through Digital Storytelling.” American Anthropological Association 107th Annual Meeting, Poster Session.

International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

2015 Chart 2.2, Measuring the Information Society Report, 2015; International Telecommunications Union (ITU); accessed April 2017. http://www.itu.int/en/ITUD/Statistics/Documents/publications/misr2015/MISR2015-w5.pdf

Leggett, Kate.

2014 Trends 2015: The future of customer service, Forrester Research, Inc. December, 2014.

Kelley, Beth.

2011 Moving like a kid again: an analysis of Parkour as free-form adult play. Master’s Thesis. Western Washington University.

Kelley, Beth

2015 Social media analytics: What it’s good for, and what it’s not. May 26, 2015. Access April 2017. http://www.deloittedigital.com/us/blog/social-media-analytics-what-its-good-for-and-what-its-not

Kozinets, Robert V.

2010 Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online. London: Sage.

Palmer, Doug; Eric Piepho, and Jennifer Buchanan.

2015 Informed Customer Care: The role and opportunity of social to evolve the customer experience. CMO.Deloitte.com September, 2015. https://cmo.deloitte.com/xc/en/pages/articles/great-customer-care-starts-with-social-listening.html

Pink, Sarah, et al.

2016 Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: Sage Publications.

Poynter, Ray.

2010 The Handbook of Online and Social Media Research: Tools and Techniques for Market Researchers. John Wiley & Sons.

Real Time Statistics Project.

2017 Real Time Statistics Project, accessed July 2017: http://www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/

Reid, Louise F.; Heather F. Ross, and Gianpaolo Vignali.

2016 An exploration of the relationship between product selection criteria and engagement with ‘show-rooming’ and ‘web-rooming’ in the consumer’s decision-making process. International Journal of Business and Globalisation (IJBG), Vol. 17, No. 3, 2016.

Schoeller, Art, et al.

2014 Connect the dots between customer self-service and contact centers, Forrester Research, Inc.

Vaccaro, Angel; Mark Reuter and Beth Kelley.

2016 From Pre-History to the Information Age: How digital brought commerce and service back to the customer. CMO.deloitte.com October, 2016. https://cmo.deloitte.com/content/dam/assets/cmo/Documents/CMO/us-cmo-lessons-from-ancient-commerce.pdf