You’ve probably been there—in a security line at Laguardia airport, still fuzzy with jet lag. I stood in one recently—just a few days after returning from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia—and certain quotidian details of life in the US were still jumping out in shocking relief.

In front of me were two women and a baby around 18 months old; perhaps mother, daughter, grandmother. In a sudden gesture the older woman got out of line, hastily bid her goodbyes, and ran off. Why run away like that, leave her daughter and granddaughter just standing there in line rather than spend the mere minute or two more it would take see them go through? Did she have an appointment to keep? Was she eager to avoid an extra charge at airport parking?

I was surprised because this casual scene in the US is an unlikely one in Ethiopia. There, relations with people matter more than almost anything else, and time is not a precious commodity; time extends, “time is your friend” I heard there.

As I mused on this, the toddler, adorably cute and out of her stroller, sat down on the floor. Her mother did not pick her up, but instead asked the pre-verbal girl if she were tired and told her to “power through” because they still needed to get to the gate and on to the plane. This time it wasn’t surprise I registered but a form of shock and horror. My memory took me back to the exit customs line in the airport in Ethiopia, late at night, where the babies and children were carried on backs and arms. Oh, take me back to that place where demonstrating affection and care for others are what matter, and virtually no one would tell a tired 18-month old to “power through.” More likely, “ayzoh” or “ayzosh” would be softly and lyrically intoned, a form of first aid that basically communicates: I understand, don’t worry, I feel for you, it will all be okay, you’ll make it.

I also thought of the way baby strollers are being used to sell goods on the streets of Addis Ababa.

This trip was not my first to Addis; I’d been there many times. And this use of baby strollers struck me as an innovation. In the past, I saw young men carry these wares. They would just carry an open box, or sometimes use a strap to harness it on, somewhat akin to American “cigarette girls” of the 1930s and ’40s.

On this recent trip I was learning Amharic, not conducting research. But it is difficult to quiet the anthropologist and consumer researcher parts of myself and one thing that really caught my imagination in Addis were the mannequins.

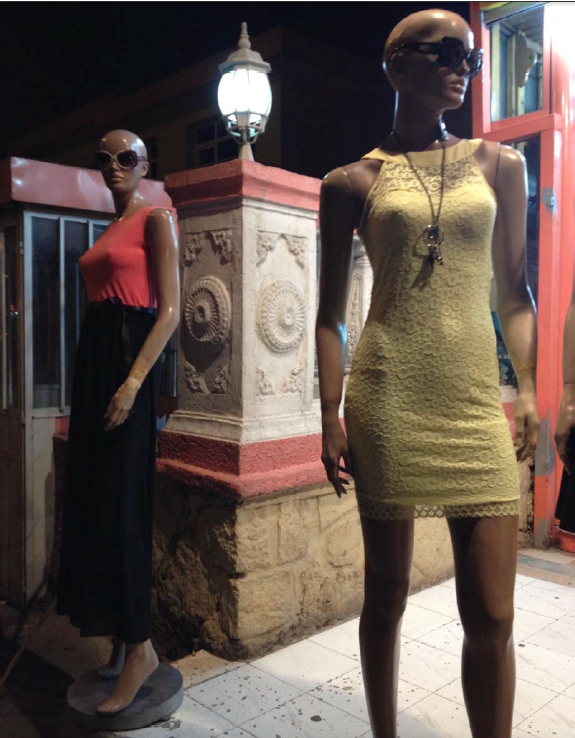

They line up in front of clothing stores, perched at the entrance. Here they are as if waving at one of the traditional blue and white Lada taxis, now blue and white (or yellow) Toyotas.

It can be a bit surreal to be among them, as if you’re in a Rod Serling Twilight Zone episode. The mannequin children can seem especially bizarre. Perhaps some version of the 1968 Night of the Living Dead movie comes to mind.

The mannequins sometimes have signs wrapped on their heads. Here the large man’s paper announces jackets; the one with the black shirt speaks of sweaters and the sign taped on the jacket reads leather shoes.

The mannequins made me think that I needed to look back at Susan Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp’”—there must be a link there. Of course, there are many: the mannequins are a sensibility, an aesthetic, there is artifice and stylization. But for now, I’ll stick with Sontag’s Note 55: “Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment.”

I am not alone in this fascination. In fact, fascinated others have photographed some of the exact same mannequins. There is something simply alive and playful about the way the mannequins are displayed that attracts attention. It is art.

At the same time, I knew that my interest had something to do with difference, that there was something surprising going on, something outside of my quotidian expectations for mannequins. Outside-of-store placement was one thing. This placement, made possible by the temperate climate, had bring-to-life effects that aren’t typical in places like New York. In the light Addis breeze, mannequin dresses move with the wind.

I tried to look at the details. I noted the bald heads of the women. If caps or hats are typically added to the male mannequins, by and large the females are left bareheaded, even when they’re accessorized with sunglasses. The multiple bare heads create quite a look in a line.

The trousers on the male models are often left open. No: Men in Addis Ababa do not routinely wear trousers that way. It’s a design convention and aesthetic flair that lives for the mannequins. Open belts and bulging pockets for men are also noticeable.

At a quick glance the man on the far right looks real. But then you see the rock at his feet, his neck tethered to the sign behind him.

In this mixed gender bald lineup, the woman on the left doesn’t look real at all, and nor do the four men. Yet you have the feeling of movement, as if the men are ready to go out on the town, if only the cords holding them in place would allow it.

You somehow feel a sense of the bodies inside, even if these are not real bodies. You get a sense of the body inside the yellow dress. Our attention is brought to the whole being, not just the clothes.

It would be easy to focus on the cobbled together nature of many of the mannequins. The mixed arrays of many stores, and the mix-and-match of individual body parts, are sometimes striking: here are dark hands on a light mannequin and an awkward right hand attached to a left arm on the sitting mannequin next to her.

This cobbling together, along with the crumbling mannequin-blocked pavement, could easily move you to tales of lack and economic challenges. Are many—if not most—of these mannequins already used or abused by the time Ethiopian storekeepers wield their craft? Undoubtedly.

Yet, more telling and important than these narratives of privation or hardship, the existence and proliferation of the outdoor mannequins are signs of the active participation of Addis residents in a global economy, both culturally and financially. Note that both Nike and Chanel branding is represented.

Ethiopia’s economy has experienced double-digit growth over the last decade and you can see it everywhere: highways, dams, new industries; and in, on, and with outdoor mannequins.

Mannequins in Cultural Action

Store owners and other pedestrians were keenly aware of my picture taking; I was often very visible and asked permission. Most were extremely accommodating and encouraging, even pointing out how I might position myself so as not to shoot into the sunlight. But a few observers on the street felt the need to warn store owners about me. One owner agreed to the photos but remained suspicious, asking in the end if I was going to open a store

The only outright objection I heard was from the owner of a traditional Ethiopian clothing store. She voiced a fairly strong “no,” softening her interdiction with the rationale of protecting the designs.

Reviewing my photographs, I realized that traditional clothing stores positioned mannequins inside. Do these stores ever put them on the street? Not that I saw. Are the stores always green? Even more difficult to say, but it’s clear that the traditional clothes are differentially valued. Unquestionably, they are objects that hold a special place of value and pride; they are worn on special and ceremonial occasions by many people, even if not day-to-day. They live in the realm of highly valued traditional culture, not the realm of playful everyday popular culture and commerce.

Mannequins are called ashangulite in Amharic. Literally translated, this means doll. Some of the store owners or employees seemed happy to accommodate my photo taking with their own play with the mannequins as a kind of doll. This man put his hand on the shoulder of the mannequin and mimicked its engagement with suitcases. It was fun.

The mannequin theme—and the mannequins-are-alive theme—have also been picked by the popular Ethiopian comedian, Filfilu. If you watch the short video Fat Model, even without understanding the words, you can see some of the conventions and assumptions around mannequins in exaggerated comedic action (and have a laugh). Filfilu, after accepting a job as a mannequin, creates one problem after another for the owner and the business: he cannot help but react when a child bites his hand; others want to have the clothes he is wearing, and so on. The mannequins are participants in popular culture.

In the end, the mannequins are part of contemporary Addis, a city currently endowed with economic well-being and part of the global economy. The mannequins are simply part of the living texture of bustling and busy Addis Ababa, side-by-side with the ubiquitous mobile phone.

0 Comments