Showcasing a sixteen-month ethnographic study of a coalition to end homelessness in Western Canada, we show how the integration of two theoretical perspectives—institutional logics and negotiated culture—can be used as complementary, yet distinct lenses to better inform the practice of cross sector partnerships which tackle the world’s wicked problems. In doing so, we highlight how we were able to holistically capture the meaning systems at work in such multi-faceted partnerships resulting in a better understanding of how partnerships can work across difference to affect positive social change. In particular, we capture how multiple stakeholders make sense of a partnership’s identity in a variety of different ways based upon meaning systems with which they identify at multiple levels as well as how they enact bridging skills across meaning-related boundaries to promote more effective partner interface.

Keywords: cultural dynamics, negotiated culture, institutional logics, cross sector partnerships

INTRODUCTION

Multi-faceted societal challenges such as poverty or homelessness cannot be solved by any one organization. These wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, 1973) are beyond the capabilities of separate organizations in the public, private, and non-profit sectors (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a) and span globally across differentiated contexts. Insights into the development of cooperative collaboration in the form of interorganizational relationships that don’t rely on market or hierarchical governance mechanisms are needed to tackle these multi-faceted societal challenges (Koschmann, Kuhn, & Pfarrer, 2012; Lawrence, Hardy, & Phillips, 2002; Selsky & Parker, 2005). Yet, partnerships that cross organizational and cultural boundaries decidedly bring together a variety of meaning systems with different assumptions about work values and practices (Barkema et al., 1997; Brannen & Salk, 2000). They do so at multiple levels – individually, organizationally, and sectorally (e.g., Murphy, Perrot & Rivera-Santos, 2012; Rivera-Santos, Rufin & Kolk, 2012), and the management and governance of these collaborative arrangements is a daunting task. What’s more, the difficulty of managing multiple meaning systems in such collaborations is further amplified by blurred organizational boundaries (Rivera-Santos & Rufin, 2011). Ethnography which typically utilizes uni-dimensional frameworks developed from the study of cultural dynamics in single organizations (Cunliffe, 2010) are not able to fully inform research and practice around the complex cultural realities of such cross-sector partnerships.

Notwithstanding, there exists organizational scholarship that studies the interaction of meaning systems within and between organizations in a more dynamic and heterogeneous manner that can inform ethnographic practice to help solve such multi-faceted problems facing us today. This body of research has been developed in two separate research streams: institutional logics in institutional theory (e.g. Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury, 2012) and negotiated culture in the international management literature (e.g., Brannen, 1994; Brannen & Salk, 2000), which taken together, can inform the study and practice of such complex organizational partnerships. We argue that utilizing these two perspectives as complementary, yet distinct, lenses when combined with the ethnographic method can result in richer and more complete analyses of cross sector partnerships tackling the world’s most wicked problems. By exploring the synergistic intersections between perspectives, it is our hope that this paper will help inform theoretically integrative ethnographic practice broadening the lenses from which we draw in order to more effectively investigate and understand cross sector partnerships.

To elucidate our arguments, we utilize a multi-site ethnographic study of the Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness Society (Coalition) located in Victoria, British Columbia. The Coalition is a partnership involving all levels of government, service providers, business members, the faith community, post-secondary institutions, private citizens and the homeless themselves focused upon effectively ending homelessness in the Greater Victoria area. Homelessness is a wicked problem because there is not a definitive formula for tackling it, it is context dependent and the symptoms of homelessness, such as lack of housing, are usually symptoms of larger systemic challenges (Rittel & Webber, 1973). By utilizing the synthetic methodological orientation introduced within, we were able to holistically capture the heterogeneous meaning systems at work in this complex organizational arrangement. This study led to a multi-layered, multi-perspective understanding of how distinct organizational actors made sense of the partnership’s identity and the bridging skill sets needed to negotiate across multiple organizational boundaries in order to facilitate the partnership.

In what follows, we briefly review ethnographic research in organization studies, highlighting how the extant literature has largely stopped short of capturing the complex cultural reality of organizations that are made up of multiple partners of the kind needed to solve today’s pressing global problems. Particularly lacking is an understanding of the complexity of negotiating a working culture in multiple-stakeholder alliances such as cross-sector partnerships where there is often little agreement in culturally-based meaning systems within and between organizations. We then discuss the benefits of moving beyond a solitary theoretical lens to merging two hither-to unrelated perspectives – institutional logics and negotiated culture – to better inform our understandings of such complex organizations. We show how this synthetic orientation helped us understand and document the reality of the Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness in Victoria, with the goal of informing future ethnographic research and practice around cross-sector partnerships seeking to tackle wicked societal challenges.

ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH AS A MEANS TO CAPTURE CULTURAL COMPLEXITY IN CROSS SECTOR PARTNERSHIPS

Ethnography emphasizes the importance of studying people and processes in natural contexts to grasp the complexity of organizational life. It has participant observation as its central methodological component involving long-term engagement in the field setting in order to produce rich insights about the day-to-day realities of organizational life and its associated cultural components in a particular setting (Cunliffe, 2010). As such, ethnographic understanding is developed through close and long-term exploration of the field site. Indeed, the extant ethnographic-based literature in organization studies has documented how assumptions about work and associated practices, or culturally-based meaning systems, play out over time in organizations among involved actors (e.g. McPherson & Sauder, 2013; Ravasi & Schultz, 2006). Yet, this work has been based predominantly on one organization and primarily at one level of analysis. Therefore, it has not fully captured the cultural complexity faced by today’s complex organizational realities, particularly cross-sector partnerships – the coming together of organizations from different sectors to deal with multi-dimensional societal challenges (Crane & Seitanidi, 2014) that are wicked in nature.

In such multi-faceted collaborative partnerships, individual actors bring with them the sense-making and distinct understandings of the way things should be done based on their home organization’s culture. As such, in order for a cross sector partnership to achieve its goals, the diverse meaning systems brought to the partnership from each actor representative of the organizations that make up the partnership must necessarily be negotiated (Brannen, 1994, Brannen & Salk, 2000). Partners collaborating across sectors are also typically quite diverse in terms of the meaning systems and associated practices, or institutional logics that guide a given institutional order (Le Ber & Branzei, 2010; Rivera-Santos & Rufin, 2011; Rivera, Rufin & Kolk, 2012; Selsky & Parker, 2005; Vurro et al., 2010). An institutional logic refers to the macro-level belief systems that shape thoughts and influence decision-making processes in organizational fields (Friedland & Alford, 1991; Ocasio, 1997; McPherson & Sauder, 2013). Within cross sector partnerships there is likely to be a plurality of institutional logics at play (Jay, 2013; Le Ber & Branzei, 2010; Murphy et al., 2012; Vurro et al., 2010).

In sum, the multiple meaning systems at play within cross sector partnerships at multiple levels have the potential to make research and practice in this area an incredibly daunting task for ethnographers.

UTILIZING UNI-DIMENSIONAL LENSES IN ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH AND PRACTICE: BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES

To study the interaction of meaning systems within and between organizations dynamically, researchers have advanced two largely, parallel research conversations: institutional logics in institutional theory (e.g. Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury, 2012) and negotiated culture in the international management field (e.g., Brannen, 1994; Brannen & Salk, 2000), to which we now turn.

Negotiated Culture

This perspective focuses on how people from distinct national and organizational cultures with different meaning systems are able to interact in shared work environments such as international joint ventures (IJVs) and M&As (e.g., Brannen & Salk, 2000). Building on the concept of negotiated orders developed by Strauss (1978) and further elaborated by Fine (1984) in the field of sociology, negotiated culture provides ethnographers with a lens by which to obtain an understanding of how diverse meaning systems interact within complex cultural organizations over time (e.g., Kaghan et al. 1999). While the empirical work from the perspective has primarily been carried out in the negotiation of disparate national cultural meaning systems within the private sector, the components of the perspective are applicable to a variety of different focal points of culture such as national, organizational, and occupational cultural differences. Brannen (1994), for example, examined the coming together of two distinct national culture groups in an organizational work setting involving a Japanese takeover of a US paper plant. Extending this work through ethnographic study, Brannen and Salk (2000) developed a dynamic process model of negotiated culture to demonstrate how organizational culture evolves in dynamic interpersonal negotiations of day-to-day issues that arise from clashes in meaning systems. By and large, though, this perspective has not captured the variety of meaning systems in which organizations are often embedded, beyond a focus on the interface between national and organizational cultural systems.

Institutional Logics

The institutional logics perspective conceptualizes society as an inter-institutional system of societal sectors, where each sub-system or institutional space represents a different set of expectations for social relations and human and organizational behavior (Friedland & Alford, 1991). In doing so, it accounts for the notion that organizations are often operating in the presence of multiple institutional logics (Thornton et al., 2012). To date, institutional logics research has offered a better understanding as to how the practices of organizational actors are embedded within institutional spaces; including, for example, how changing logics at the field level influence the strategies and practices of organizations (Thornton, 2004).

Yet, much of the institutional logics research to date has focused on the macro level of analysis (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008; Thornton et al., 2012), with few examples of ethnographic work carried out in this tradition exploring the microdynamics of logics within organizational life. One exception to this statement is McPherson and Sauder’s (2013) ethnographic study investigating how logics are utilized in the interactions of actors involved in a drug court as it does offer a micro account in terms of the content of the actors’ interactions and the logics at play in this context. However, the authors stop short of explaining how logics are negotiated by actors on the ground as it relates to a process based perspective. While McPherson and Sauder (2013) mention some structural constraints that affect how logics are enacted, they do not readily incorporate these dynamics into their full analysis or account for other micro-level filters, such as actors’ roles and cultural identities, which may very well affect how these meaning systems are experienced in the everyday lives of organizational actors.

As the above discussion illustrates, we argue that each perspective, in and of itself, is not sufficient for ethnographers to capture the increased complexity in meaning systems found within today’s inter-organizational arrangements, which is driven by operations across differentiated and blurred organizational boundaries.

DISTINCTIONS AND INTERSECTION POINTS BETWEEN PERSPECTIVES

When comparing the negotiated culture and institutional logic perspectives side-by-side, we contend that the distinctions as well as the opportunities for ethnographers to utilize both perspectives in concert to more holistically capture the complex cultural realities of cross sector partnerships becomes clear. We illustrate the distinctions and overlaps in Table 1 and expound upon these comparison points below, focusing in particular on methodological emphasis, contextual influences and levels of analysis.

Table 1. Comparison of the Negotiated Culture and Institutional Logics Perspectives

| Negotiated Culture | Institutional Logics | |

| Key Management Scholars within each Perspective | Brannen, 1994; Kaghan, Strauss, Barley, Brannen & Thomas, 1999; Brannen & Salk, 2000; Yagi & Kleinberg, 2011 | Thornton & Ocasio, 1999; Thornton, 2004; Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury, 2012 |

| Methods of Analysis | Ethnographic Qualitative |

Qualitative Quantitative |

| Phenomena of Interest | Interaction between Culture, Individuals and Situation, Meaning, Communication, Worker Satisfaction & Commitment, Emergent Processes, Constraints & Impact of Physical Environment, How Culture Evolves as Subcultures Come into Contact and are Negotiated in Practice by Individual Actors | Institutional & Organizational Change, Meaning, How Institutional Logics Enable & Constrain Action Availability, Accessibility, & Activation of Institutional Logics to Actors |

| Levels of Analysis | Micro Social Psychological Individuals Groups Organizations |

Micro Social Psychological Macro Sociological Individuals Groups Organizations Markets Fields Society |

| Ontology—Nature of Being | Subjective Rationality Varies by Individual Experiential Antecedents Non-economic Culture as dynamic/ non-monolithic Focus on Day-to-Day Practices |

Subjective Rationality is Situated Rationality Varies by Principles & Practices of Institutional Orders Economic Varies by Institutional Order Institutional Orders are Historically Contingent |

| Epistemology—Theory of Knowledge | Symbolic & Material Socialization Decisions on Incomplete Information Culture as loose network of domain-specific cognitive structures |

Symbolic & Material Socialization Decisions on Incomplete Information Culture as institutionalized in Society (facts & myths) |

| Basis of Order | Negotiation Loose Coupling |

Negotiation Loose Coupling Organization Structure |

| Nature of Rules | Contextual Social Emergent Negotiated, Re-negotiated |

Contextual Social Emergent Institutionalized Policy Driven |

| Mechanisms of Change | Individual Interests Subgroup Interests Cultural Differences Structural Changes Require Revision of Negotiated Order |

Conflict & Contradiction in Institutional Logics Theorization Translation Sensemaking Sensegiving Attention to Events Categorization Vocabulary Use Reification |

| View of Change | Inevitable in real time Continuous |

Inevitable over historical time Continuous Punctuated |

Methodological Emphasis

The institutional logics perspective looks to uncover similarities as it relates to assumptions about work and associated practices within a given institutional sphere. For example, Pache and Santos (2013) study how work integration social enterprises manage social welfare and commercial institutional logics internally. Prior to exploring how each organization responded to these competing logics, the authors’ first step in the data analysis process was to identify and describe each institutional logic. In other words, Pache and Santos first categorize the similarities in assumptions about work and associated practices within each institutional sphere. By comparison, the negotiated culture perspective focuses on how organizations develop unique webs of meaning as cultures are negotiated in an issue-driven, idiosyncratic way within each given organizational arrangement (e.g., Brannen & Salk, 2000), typically incorporating an ethnographic based approach. In other words, scholars utilizing this lens look at differences in a given organizational arrangement. Salk and Shenkar (2001), for instance, examine the unique, emergent culture that forms in a British-Italian management joint venture. Focusing on both similarities and differences in meaning systems simultaneously offers ethnographers an avenue to utilize both perspectives in concert to more completely study and understand the variety of assumptions about work and associated practices in a given cross sector partnership setting.

Contextual Influences

The negotiated culture perspective accounts for various contextual factors that will influence organizational action in shared working arrangements involving the coming together of distinct cultures. Integral to this perspective are the notions of recontextualization (e.g., Brannen, 2004) and multicultural boundary spanning (e.g., Fitzsimmons, 2013). The former refers to the process by which organizational meaning systems are transformed when transplanted into new contexts (see Brannen 2004). The latter refers to the cross-context bridging skillsets that people who have been deeply socialized in more than one cultural context bring to the workplace (see Caprar 2011 for an ethnographic example). Contextual influences (both intra- and extra-organizational) have thus been taken up in the negotiated culture perspective. However, a direct link with institutional logics research in order to more holistically capture contextual influences within the organization has not been made. By comparison, the institutional logics perspective focuses on how institutions, via logics, shape stability, heterogeneity and change in individuals and organizations (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008). Quirke (2013), for example, conducts an ethnographic investigation of a private school field in Toronto, Canada and elucidates how it is characterized by segmentation where individual private schools respond to institutional pressures in different ways.

While the negotiated culture and institutional logics perspectives tend to focus on different factors that influence individual and organizational action, they share a common emphasis on the interplay between individual agency and structure. One important component of the negotiated culture perspective is that there is a relationship between the structural conditions of the organization and the negotiation process. Strauss (1978) argues that specific negotiations are contingent on the structural conditions of a given organization. These include such structural properties as the balance of power among parties and the number and complexity of the issues involved (see Brannen & Salk, 2000 for an ethnographic example). Similarly, the material practices and symbolic systems that make up a given institutional logic are available to individuals, groups and organizations to further elaborate, manipulate and utilize to their own advantage (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008), referred to as embedded agency (Greenwood & Suddaby, 2006, see above two mentioned examples: Quirke, 2013; Pache & Santos, 2013). Thus, both perspectives account for structural components (whether they be at a macro, meso or micro level) as both constraining and enabling mechanisms in shaping organizational and individual action. And, when used in concert, they can provide ethnographers with a means by which to more fully capture the multi-faceted contextual influences at work that shape individual and organizational action in cross sector partnerships.

Levels of Analysis

Negotiated culture researchers have tended to explore phenomena centered on a plurality of meaning systems at the meso and micro levels (e.g., Brannen, Liker, & Fruin, 1999; Yagi & Kleinberg, 2011). Brannen (1994), for example, elucidates how culture is negotiated at the meso and micro levels of analysis in a Japanese takeover of a US paper manufacturer. In applying this perspective where it concerns cross sector partnerships specifically, the ethnographer is primarily able to capture the distinct national cultures that are brought together in a given organizational arrangement as well as the intercultural interactions that occur among individuals and groups situated within them.

By comparison, institutional logics researchers can be represented by two ideal-typical views designed to address different research questions at different levels of analysis. The first conceptualizes institutional logics as macro structures associated with societal-level institutional orders. As Besharvo and Smith (2014) point out the focus of this research is on multiple meaning systems, even when they are instantiated within a single organization. The more recently developing second view incorporates the micro level by conceptualizing institutional logics as emergent properties of communication (language and symbols) and material practices and artifacts shaped by both higher-level institutional orders and by organizational and field-level variations and adaptations (Thornton et al., 2012; Ocasio, Lowenstein, & Nigam, 2015). In spite of this second emerging view, though, the main emphasis is still on how individuals and/or organizations are shaped by and/or respond to these macro-level meaning systems. For example, Jay’s (2013) ethnographic investigation details how macro-level institutional logics play out differently within a US-based energy alliance from its inception to present day, transitioning the identity of the partnership from a client service business, to a public service nonprofit to a complex hybrid organization. While Jay (2013) does give mention to some external perspectives that affected the instantiation of the logics in the cross sector partnership, including the author himself, he does not fully account for the meaning systems and associated work practices of the involved organizations and individual actors that resided within them that could have affected how these logics played out within the partnership over time. As such, in applying this perspective to cross sector partnerships, the primary levels of analysis the researcher is able to capture, in particular the institutional orders and field logics in which a given cross sector partnership and its associated actors are embedded.

APPLICATION OF INTEGRATIVE ETHNOGRAPHIC FRAMEWORK TO CROSS SECTOR PARTNERSHIP TACKLING HOMELESSNESS

Research Setting

We engaged in a 16-month ethnographic study of a coalition to end homelessness in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. The Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness (Coalition) brings together actors from over forty organizations and associations – involving public, private and nonprofit sectors – with the purpose of ending homelessness in the region. People in the Greater Victoria region experience homelessness for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to, seniors being displaced as a result of rent increases, women and their families escaping abusive relationships, the working poor, youth leaving government care with no transitional help and low-income families unable to find affordable housing situations. While some people experiencing homelessness are, indeed, mentally ill and/or addicted to drugs or alcohol, it is a common myth that all people fall into this category (Coalition, 2009), one that the Coalition actively works to communicate to the public. The issue of homelessness, particularly in the Greater Victoria region, is one of significance. Indeed, it was reported in 2014 that Victoria has the highest per capita deaths of homeless people in all of B.C. (Petrescu, 2014).

The Coalition was formed in early 2008, following former Victoria Mayor, Alan Lowe’s, four-month task force in 2007 to recommend a service model and business plan to better address cycles of mental illness, addictions and homelessness in the Greater Victoria area. The decision to form this partnership was considered to be a significant and crucial milestone in the fight to end homelessness in the community. As one Executive Director for a major homelessness service provider in Greater Victoria as well as Chair of the Downtown Service Providers noted:

I have been doing this work for years in Victoria, and I have never seen a community rally behind a cause in the way Victoria has responded to the Mayor’s Task Force action plan. Our community is on a roll and this (Coalition) is the key to keeping the right people and the money focused on this issue. We’re on the cusp of something great here.

By working with partner organizations and associations, the Coalition coordinates efforts and helps increase awareness and commitment to end homelessness in Greater Victoria.

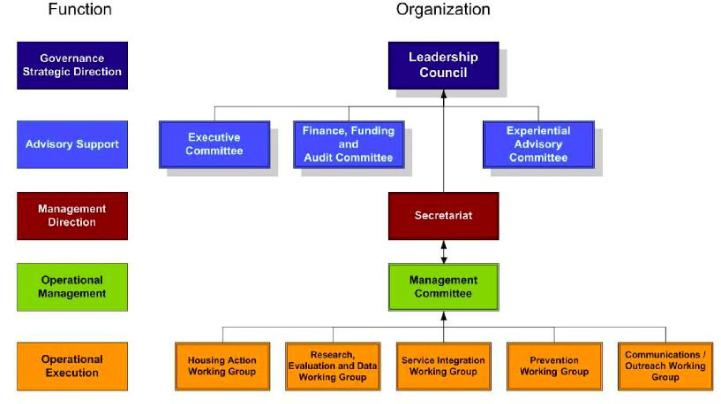

Organizationally, the below figure provides an overview of the leadership and operational makeup of the Coalition.

Figure 1. Coalition Governance Structure

The Leadership Council provides governance and strategic oversight and is responsible for all key decisions involving the Coalition. An executive committee and a finance and audit committee, sub-sets of the Leadership Council, provide advisory support to this body on an ongoing basis. In 2013, the Coalition developed the social inclusion advisory committee, comprised of individuals with homelessness experiences in the Greater Victoria area, who also provide advisory support to the Leadership Council. The Coalition is coordinated and operated via a small team (the Secretariat), including an Executive Director who oversees the partnership and provides overall coordination between the involved committees and working groups. Primary operational support is provided to the Secretariat via an operations management committee. The Management Committee aides the Secretariat in developing and implementing the Coalition’s ongoing business plan and provides management direction and supervision to the working groups. Five working groups are involved in the ongoing implementation of the Coalition’s business plan, focused on particular priority areas of the tri-sector partnership; namely, community engagement, prevention, homelessness prevention fund, housing and service integration, respectively. As illustrated by the multi-faceted organizational makeup of the Coalition, the partnership is managerially complex and entails a high level of engagement among actors. As well, the Coalition involves a variety of individuals, organizations and associations in the public, private and nonprofit sectors. For example, within the Leadership Council alone, there are a variety of different actors represented.

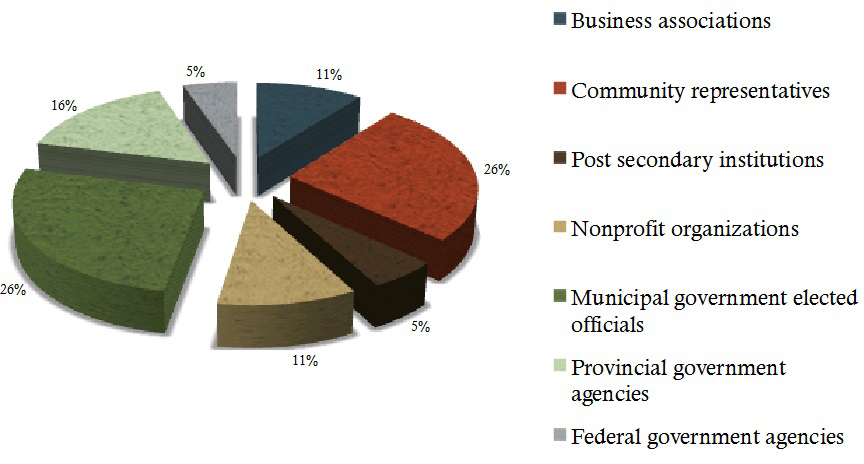

Figure 2. Composition of Leadership Council

These characteristics, collectively, made the Coalition an ideal setting in which to investigate how a complex organizational arrangement with blurred boundaries works through multiple meaning systems, or assumptions about work and associated practices, over time in its efforts to tackle a wicked problem.

Data Gathering Overview

In accordance with the ethnographic method, our principal means of data collection involved participant observation, both formal and informal, at Coalition meetings and community events related to homelessness, as well as semi-structured interviews with key actors involved from a variety of different sectors, organizations and vantage points within the collaborative partnership. In carrying out this work, we took up the holistic ethnographic approach conceptualized by Moore (2011), which recognizes and incorporates the distinct groups and perspectives involved in developing an overall narrative of a given situation. As well, we had access to a variety of archival documentation including meeting minutes, strategic plans and annual reports dating back to the Coalition’s founding in 2008. In total, our data set included 2,500+ pages of documentation and over 300 documents.

Synthetic Methodological Orientation

We utilized the notions that institutional logics account for similarities of meaning in a given institutional space and negotiated culture accounts for differences within a given organizational arrangement to tease apart meaning systems at the sectoral and organizational levels. By focusing on similarities in meaning systems across informants and associated archival documentation, we were able to begin articulating the key institutional logics at play within the cross sector partnership. To provide an illustrative example, we noticed emerging similarities in the way that most participants with a business based background discussed the partnership, frequently using phrasing focused upon “efficiency,” “cost savings” and an “action” orientation. By closely reviewing interview transcripts, observing behaviors in meetings as well as examining the archival documents, with a particular focus on places where business professionals were highly involved, we arrived at the logic of efficient action, a field level manifestation of the logic of the market (Thornton et al., 2012). By focusing on differences in meaning systems within each organizational entity in which informants were embedded, we were able to begin making sense of the organizational cultures of each respective entity. For instance, to continue with the same group as referenced above, for the business professionals interviewed, while there were many similarities across these participants, there were also distinct differences. By looking at the differences in these actors’ responses, closely examining participant observation notes and viewing the relevant documentation for each given business organization, we were able to articulate the unique meaning system of each given organizational entity within this institutional space (logic of efficient action).

Findings: Multiple Understandings of Organizational Identity

Many participants described the Coalition’s identity (its overall vision and mission) as being “well understood,” “clear” and that “actors were on the same page.” As well, the written documentation of the Coalition’s identity as a partnership focused on ending homelessness in Greater Victoria has remained relatively unchanged since it was founded in 2008. Yet, we discovered that there were actually a variety of different meanings that involved actors attributed to partnership, homelessness and ending homelessness.

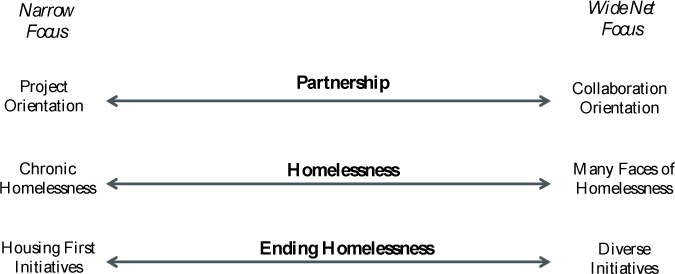

Figure 3. Continuum of Identity Understandings

As the above figure shows, these various meanings ascribed to partnership, homelessness and ending homelessness tended to fall on a continuum ranging from a narrow to a wide net focus or approach. For instance, as it relates to the meaning of homelessness, some actors indicated that it was important for the Coalition to focus specifically on those experiencing chronic homelessness (i.e., those with long-term or repeated episodes of homelessness) since this group is the most vulnerable. Those who held this view concerning the meaning of homelessness when it came to the Coalition’s identity tended to focus on housing related initiatives as the primary vehicle for ending homelessness. Consider the following statement made by the third Executive Director:

So the focus of the organization has almost always been chronic homelessness, right, and the and how many people are experiencing chronic homelessness and what the definition of chronic homelessness is. That has almost from the get go been the focus of our organization and it remains our top priority.

Others, though, believed that an inclusive approach needed to be taken that addressed the many faces that homelessness can take, including those who are couch surfing, do not have access to affordable housing, etc., alongside those who are ‘visibly’ experiencing homelessness. The latter group tended to emphasize a wider array of initiatives in addition to focusing primarily on housing related efforts, such as prevention related activities and/or initiatives to minimize the effects of homelessness. As one involved partner emphatically put it:

I really get hot under the collar when people say we should prioritize those that are chronically homeless. Well, no bloody wonder, okay so that’s almost a useless statement in one way…they’re flooding in like massive amounts. You’re never gonna take care of just those chronically homeless. If you just focus on that you’re gonna lose the war…You’re never gonna resolve the problem if you just focus on that part of the society.

By tracing the various meanings that involved participants ascribed to the Coalition’s identity in this ethnographic study as we utilized both perspectives in our analysis, we were able to arrive at a better understanding of how actors actually made sense of the partnership’s identity in a variety of different ways based upon meaning systems that they identified with at multiple levels. We discovered that these different understandings were not simply a current day challenge, but rather dated back to the very conception of the multi-stakeholder partnership.

Of the individuals we interviewed who were involved in the early stages of the Coalition, while many described the organization’s central focus on chronic homelessness (from the beginning) a few others felt that chronic homelessness was just one piece of a much larger puzzle in which the Coalition was grappling. In recognition of these various perspectives, one former Leadership Council director involved during the initial founding of the organization put it this way:

One of the challenges I think from the very beginning was defining what is the goal of the Coalition and when we say our goal is to end homelessness what is it that we mean by that?

We also realized that each and every individual in the Coalition made sense of his/her involvement in a different manner. These perspectives colored how members viewed the Coalition’s very identity, the result being a multitude of meanings related to its organizational identity, which were, more often than not, implicit in nature. Differences in perspectives stemmed from each individual involved approaching the Coalition table with multiple “hats” simultaneously, including, but not limited to, the organization and/or stakeholder group he/she represented and the sector(s) in which his/her organization was situated (e.g., nonprofit, government, business). As well, each involved actor held an individual stance on the Coalition and the issue of homelessness, which may or may not have aligned with the group and/or organization he/she represented. This points to the complexity of addressing a wicked problem, in this case homelessness, as there are many different features of the problem and many different ways in which involved actors define the focal issue, which makes it difficult for a cross sector partnership to come to a working agreement as to approaches to resolving the focal issue at hand1.

By incorporating both the institutional logics and negotiated culture perspectives simultaneously into our analysis, we were able to arrive at a more complete understanding of the variety of contextual factor that shaped each actor’s perspective in approaching the Coalition. An institutional logics lens allowed us to categorically capture the macro-level meaning systems that manifested themselves in the partnership context. As one example, a logic that surfaced in this context was that of social justice, a field-level manifestation of the logic of profession (Thornton et al., 2012) within the homelessness arena. Individuals who ascribed to this logic, commonly those working directly with the homelessness population, such as frontline service providers, focused on the human element of homelessness, rather than simply viewing the issue in terms of a macro level systems challenge alone. Key words and phrasing commonly used include “human rights,” “social inclusion,” “direct connection to homelessness,” “moral imperative” and “social change”. By contrast, the negotiated culture perspective aided the researcher in better understanding how the actors involved made sense of its identity as a cross sector partnership to end homelessness in a variety of ways based upon meaning systems at multiple levels, including but not limited to institutional logics, which interacted over time to shape and alter the partnership’s identity.

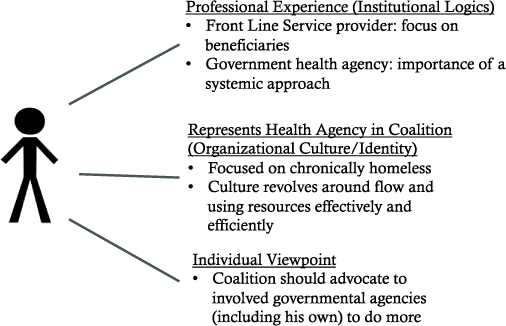

We profile one Coalition actor as a representative example whose viewpoint would not have been captured in full by focusing on either perspective in isolation.

Figure 4. Example Profile

David (pseudonym) has been involved in the Coalition since it was founded in 2008. David’s professional background consists of time spent working as a case manager for a service provider as well as an operational officer for a major governmental health agency. During our two interviews, David emphasized the importance of keeping the beneficiaries a given group is trying to serve at the forefront, in this case those experiencing homelessness themselves (social justice logic). At the same time, David talked about the importance of a systemic approach that considers prevention based solutions, such as addressing youth in foster care at risk of homelessness, alongside housing initiatives (root causes logic). Organizationally speaking, David relayed to me that his organization, a major health agency, is most focused on the high needs group within the homelessness realm (i.e., those experiencing repeated episodes of homelessness) and desires for the Coalition to think outside the box in terms of generating housing resources beyond new capital projects in order to ensure that resources are being used effectively and efficiently. He also described to me the health organization’s culture, “…revolv(ing) around flow and getting people out of the beds,” which informs how he approaches the Coalition as an organizational representative. Personally speaking, David expressed to me the importance of addressing homelessness, a major societal challenge, and that the Coalition should advocate to involved governmental agencies such as his own in order to do more to help solve the issue, a viewpoint that did not represent the official stance of his organization. In contrast, one of his colleagues who worked within the same health agency felt that the organization was significantly contributing to the Coalition’s work.

While we admit that there is ‘messy’ overlap between the two perspectives, we also contend that we would not have been able to capture the variety of contextual factors that shaped how Coalition actors made sense of the cross sector partnership’s identity by utilizing a solitary lens. When combining this integrative theoretical approach with the ethnographic method, we were able to provide the Coalition with an in-depth understanding of the variety of different meaning systems at work. In the Coalition’s case, these multiple understandings of identity were rather implicit in nature. As a result of our findings, therefore, we recommended that the Coalition consider making explicit communications with current and incoming partners an active and ongoing priority (e.g., communicate exactly what is meant by partnership, homelessness, etc.) as this study revealed that actors held many different perspectives on the Coalition’s focal mission even as they were regularly reminded of it.

Findings: Bridging Skill Sets to Navigate Across Meaning-Related Differences

This synthetic methodological orientation also allowed us to surface the key bridging skill sets that facilitate boundary spanning activities within the Coalition. Boundary spanning can be defined as activities that promote partner interface across organizational, geographic and sectoral boundaries (Manning & Roessler, 2014). Boundary spanning is particularly crucial in cross sector partnership settings characterized by multiple meaning systems at multiple levels and that span a variety of boundaries – sectorally, organizationally and individually.

Partnership Commitment – Ability to focus first and foremost on the aims of the partnership including the key wicked issue that the partners have come together to address rather than calling attention to organizational and/or sectoral differences between them.

Awareness of Complexity – The ability to realize that the wicked issue at hand is very multi-layered and will involve multiple organizations and sectors working together, each with their own sets of strengths and limitations, in order to solve it effectively rather than viewing the issue solely from his/her vantage point.

Boundary Crossing Knowledge Transfer – The ability to coherently express one’s own viewpoint, including underlying assumptions, to effectively share information in a way that will be meaningful in other organizations and/or sectors rather than communicating opaquely and in the same manner regardless of the audience.

Openness to Alternative Perspectives – This refers to one’s capacity to fully understand that his/her perspective is just one out of a plethora of perspectives and demonstrates a strong willingness to actively listen to and understand others’ stances rather than viewing his/her own viewpoint as “the right one.”

Relationship Orientation – One’s ability to foster strong social capital with other actors involved in the cross sector partnership rather than seeking to move forward with one’s agenda without regard for personal relationships.

What is important to note about the boundary spanning skill sets identified is that each individual exhibiting one or more of these capabilities was only able to bridge across select organizational cultures and institutional logics involved. This finding speaks to the need for a multitude of individuals involved in cross sector partnerships to utilize boundary spanning capabilities in order to traverse the multiple meaning systems present in a holistic manner. This is particularly relevant for complex tri-sector partnerships, such as the Coalition, characterized by a variety of meaning related boundaries, culturally and institutionally speaking, that any one given individual will only be able to bridge in part.

We also discovered that actors were able to develop these skill sets over time, which points to them being learned behavioral traits as opposed to innate psychological characteristics. For example, some actors relayed to us how their opinions about homelessness had been altered over time due to their involvement within the Coalition. One Leadership Council co-chair put it this way:

Well I really enjoyed being involved in the Coalition. I think it does open your eyes. For me, Coalition me has been impactful in helping me be more empathetic towards that community to not hold them as accountable.

Others talked about how they were gradually able to see the issues at hand from alternative perspectives over time. This even occurred in cases where individuals did not have direct experience in a different professional realm, such as a business professional learning and understanding a social work perspective concerning the issue of homelessness after seeking to learn from this alternative viewpoint.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

By utilizing institutional logics and negotiated culture in conjunction with the ethnographic method, we illustrate how this synthetic orientation can be used in practice. In doing so, we highlight how we were able to holistically capture the meaning systems at work in this multi-faceted partnership at multiple levels, resulting in a better understanding of how such partnerships can work across difference to affect positive societal change when addressing wicked problems. In particular, utilizing this synthetic approach we accomplished the following: 1) we captured the numerous meaning systems that came together in the Coalition at multiple levels, which influenced how the various stakeholders viewed the partnership’s identity; 2) we were able to illustrate how the diverse stakeholders worked across these differences as a group; and 3) we were able to document how individual actors took boundary-spanning roles between their home organizations and the Coalition.. Our findings offer important implications for other types of collaborative partnerships and strategic alliances that bring together diverse actors operating across distinct working arrangements at multiple levels. In such multi-faceted arrangements the individual actors are likely to hold different and often divergent perspectives concerning the meaning of the wicked problem being addressed. In the case of the Coalition, we discovered that the various actors held diverse perspectives of the Coalition’s identity as a partnership to end homelessness even as they were regularly reminded of it. This underscores the importance of taking a holistic assessment of the sensemaking individual actors bring to such partnerships, allowing for and encouraging a negotiated, flexible and dynamic outcome regarding the identity of the organization, and making communications as explicit as much of the understandings brought to the partnerships are implicit in nature. As organizations are increasingly complex and often driven by operations across differentiated boundaries at multiple levels (Brannen, 2009), it is our hope that this integrative methodological approach will open up future pathways to more holistically understand meaning-related phenomena in multi-faceted organizational arrangements.

Sarah Easter, MBA, PhD is Assistant Professor of Management at Abilene Christian University. Utilizing ethnographic techniques, her work explores how individuals, groups and organizations work together across complex differentiated contexts. Projects include working with a coalition to end homelessness in Western Canada and a social enterprise for people with disabilities in Central Vietnam.

Mary Yoko Brannen, MBA, PhD, Dr. Merc. H.C. is the Jarislowsky East Asia (Japan) Chair and Professor of International Business at the University of Victoria. She is a Fellow of the Academy of International Business having served as Deputy Editor of the Journal of International Business Studies from 2011-2016. She holds an honorary doctorate from the Copenhagen Business School.

NOTE

Acknowledgment – The authors thank Matt Murphy, Trish Reay, Roy Suddaby and Patricia Thornton for their input and valuable suggestions on earlier versions of this work and they gratefully acknowledge the research participants of the Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness who generously shared their experiences with candor and passion.

1 We thank our session chair for pointing out this connection

REFERENCES CITED

Anheier, H. K., & Ben-Ner, A.

2003 “The Study of Nonprofit Enterprise: Theories and Approaches. Business and Society Review 105: 305–322.

Ansari, S., Wijen, F., & Gray, B.

2013 “Constructing a Climate Change Logic: An Institutional Perspective of the “Tragedy of the Commons”. Organization Science 24(4): 1014-1040.

Aten, K., Howard-Grenville, J., & Ventresca, M.J.

2012 “Organizational Culture and Institutional Theory: A Conversation at the Border. Journal of Management Inquiry 21: 78-83

Austin, J.E, & Seitanidi, M.M.

2012a “Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering bet Nonprofits and Businesses: Part 1. Value Creation Spectrum and Collaboration. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41(5): 726-758.

Austin, J.E., & Seitanidi, M.M.

2012b “Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering bet Nonprofits and Businesses: Part 2. Partnership Processes and Outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41(6): 929-968.

Barkema, H. G., Shenkar, O., Vermeulen, F., & Bell, J. H.

1997 “Working Abroad, Working with Others: How Firms Learn to Operate International Joint Ventures. Academy of Management Journal 40(2): 426-442.

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S.

2010 “Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Academy of Management Journal 53: 1419-40.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E.

2004 “Social Alliances: Company/Nonprofit Collaboration. California Management Review 47: 58–90.

Besharov, M.L., & Smith, W.K.

2014 “Multiple Institutional Logics in Organizations: Explaining their Varied Nature and Implications. Academy of Management Review 39(3): 364-381.

Brannen, M.Y.

1994 “Your Next Boss is Japanese: Negotiating Cultural Change at a Western Massachusetts Paper Plant. University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Unpublished dissertation.

Brannen, M.Y., Liker, J.K., & Fruin, W.M.

1999 “Recontextualization and Factory-to-Factory Knowledge Transfer from Japan to the United States (pp. 117-154). Oxford University Press, NY.

Brannen, M.Y., & Salk, J. E.

2000 “Partnering Across Borders: Negotiating Organizational Culture in a German-Japanese Joint Venture. Human Relations 53(4): 451-487.

Brannen, M.Y.

2004 “When Mickey Loses Face: Recontextualization, Semantic Fit, and the Semiotics of Foreignness. Academy of Management Review 29(4): 593-616.

Brannen, M.Y.

(2009). “Culture in Context: New Theorizing for Today’s Complex Cultural Organizations. In Beyond Hofstede. Culture Frameworks for Global Marketing and Management (pp. 81-100). UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Caprar, D.V.

2011 “Foreign Locals: A Cautionary Tale on the Culture of MNC Local Employees. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 608-628.

Coalition (Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness).

2009 “Annual Report 2008-09.

Crane, A. & Seitanidi, M.M.

2014 “Social Partnerships and Responsible Business: What, Why and How? In M.M. Seitanidi & A. Crane (Eds.), Social partnerships and responsible business: a research handbook (pp. 1-12). New York: Routledge.

Cunliffe, A.L.

2010 “Retelling tales of the Field: In search of Organizational Ethnography 20 Years on. Organizational Research Methods 13(2): 224-239.

Dahan, N. M., Doh, J. P., Oetzel, J., & Yaziji, M.

2010 “Corporate-NGO Collaboration: Co-creating New Business Models for Developing Markets. Long Range Planning 43(2/3): 326-342.

De Bakker, F.G., Den Hond, F., King, B., & Weber, K.

2013 “Introduction: Social Movements, Civil Society and Corporations: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead. Organization Studies, 34(5-6), 573-593.

Fine, G.A.

1984 “Negotiated Orders and Organizational Cultures. Annual Review of Sociology 10(1): 239-262.

Fitzsimmons, S.

2013 “Multicultural Employees: A Framework for Understanding How They Contribute to Organizations. Academy of Management Review 38(4): 525-549.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R.R.

1991 “Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices and Institutional Contradictions. In W.W. Powell & P.J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (pp. 232-263). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gray, B., & Purdy, J.

2014 “Conflict in Cross-sector Partnerships. In M.M. Seitanidi & A. Crane (Eds.), Social Partnerships and Responsible Business: A Research Handbook (pp. 205-225). New York: Routledge.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E.R., & Lounsbury, M.

2011 “Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Academy of Management Annals 5(1): 317-371.

Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. R.

1996 “Understanding Radical Organizational Change: Bringing Together the Old and the New Institutionalism. Academy of Management Review 21(4): 1022-1054.

Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R.

2006 “Institutional Entrepreneurship in Mature Fields: The Big Five Accounting Firms. Academy of Management Journal 49(1): 27-48.

Hardy, C., Lawrence, T. B., & Phillips, N.

2006 “Swimming with Sharks: Creating Strategic Change through Multi-sector Collaboration. International Journal of Strategic Change Management, 1, 96–112.

Hinings, B.

2012 “Connections between Institutional Logics and Organizational Culture. Journal of Management Inquiry 21: 98-101.

Hong, Y.-Y., & Mallorie, L.-A.M.

2004 “A Dynamic Constructivist Approach to Culture: Lessons Learned by Personality Psychology. Journal of Research in Personality 38(1): 59-67.

Jackall, R.

1988 “Moral Mazes: The World of Corporate Managers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jay, J.

2013 “Navigating Paradox as a Mechanism of Change and Innovation in Hybrid Organizations. Academy of Management Journal 56(1): 137-159.

Kaghan, W. N., Strauss, A. L., Barley, S. R., Brannen, M. Y., & Thomas, R. J.

1999 “The Practice and Uses of Field Research in the 21st Century Organization. Journal of Management Inquiry 8(1): 67.

Kolk, An., & Lenfant, F.

2015 “Partnerships for Peace and Development in Fragile States: Identifying Missing Links. Academy of Management Perspectives 29(4): 422-437.

Koschmann, M., Kuhn, T., & Pfaffer, M.

2012 “A Communicative Framework of Value in Cross-sector Partnerships. Academy of Management Review 37(3): 332-354.

Lawrence, T.B., Hardy, C., & Phillips, N.

2002 “Institutional Effects of Interorganizational Collaboration: The Emergence of Proto-institutions. Academy of Management Journal 45: 281-290.

Le Ber, M.J., & Branzei, O.

2010 “Value Frame Fusion in Cross-sector Interactions. Journal of Business Ethics 94(Suppl. 1): 163-195.

Lok, J.

2010. “Institutional Logics as Identity Projects. Academy of Management Journal 53(6): 1305-1335.

Lowenstein, J., Ocasio, W., & Jones, C.

2012 “Vocabularies and Vocabulary Structure: A New Approach Linking Categories, Practices, and Institutions. Academy of Management Annals 6(1): 41-86.

Manning, S., & Roessler, D.

2014 “The Formation of Cross-sector Development Partnerships: How Bridging Agents Shape Project Agendas and Longer-term Alliances. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 527-547.

McPherson, C.M., & Sauder, M.

2013 “Logics in Action: Managing Institutional Complexity in a Drug Court. Administrative Science Quarterly 58(2): 165-196.

Montgomery, A. W., Dacin, P. A., & Dacin, M. T.

2012 “Collective Social Entrepreneurship: Collaboratively Shaping Social Good. Journal of Business Ethics 111(3): 375-388.

Morris, M. W., & Gelfand, M. J.

2004 “Cultural Differences and Cognitive Dynamics: Expanding the Cognitive Perspective on Negotiation. In M. Gelfand and J. Brett (eds.) The Handbook of Negotiation and Culture, 45-70. Stanford: Stanford, CA: University Press.

Murphy, M., Perrot, F., & Rivera-Santos, M.

2012 “New Perspectives on Learning and Innovation in Cross-sector Collaborations. Journal of Business Research 6: 1700-1709.

Nwankwo, E., Phillips, N., & Tracey, P.

2007 “Social Investment through Community Enterprise: The Case of Multinational Corporations involvement in the Development of Nigerian Water Resources. Journal of Business Ethics 73(1): 91-101.

Ocasio, W., Lowenstein, J., & Nigam, A.

2015 “How Streams of Communication Reproduce and Change Institutional Logics: The Role of Categories. Academy of Management Review 40(1): 28-48.

Pache, A.C., & Santos, F.

2013 “Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Academy of Management Journal 56(4): 972-1001.

Petrescu, S.

2014 “Victoria homeless death rate ‘troubling’. Times Colonist, November 6, 2014.

Powell, W.W., & Colyvas, J.A.

2008 “Microfoundations of Institutional Theory. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin-Andersson & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (pp. 276-298). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Quirke, L.

2013 “Rogue Resistance: Sidestepping Isomorphic Pressures in a Patching Institutional Field. Organization Studies 34(11): 1675-1699.

Ravasi, D. & Schultz, M.

2006 “Responding to Organizational Identity Threats: Exploring the Role of Organizational Culture. Academy of Management Journal 49(3): 433-458.

Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R.

2009 “Managing the Rivalry of Competing Institutional Logics. Organization Studies 30(6): 629-652.

Rittel, H.W. & Webber, M.M.

1973 “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences 4: 155-169.

Rivera-Santos, M., & Rufín, C.

2011 “Odd Couples: Understanding the Governance of Firm-NGO Alliances. Journal of Business Ethics 94: 55-70.

Rivera-Santos, M., Rufin, C. & Kolk, A.

2012 “Bridging the Institutional Divide: Partnerships in Subsistence Markets. Journal of Business Research 65: 1721-1727.

Salk, J.E., & Shenkar, O.

2001 “Social Identities in an International Joint Venture: An Exploratory Case Study. Organization Science 12(2): 161-178.

Schultz, M.

2012 “Relationships between Culture and Institutions: New Interdependencies in a Global World? Journal of Management Inquiry 21: 102-106.

Selsky, J., & Parker, B.

2005 “Cross-sector Partnerships to Address Social Issues: Challenges to Theory and Practice. Journal of Management 31: 849–873.

Strauss, A.L.

1978 “Negotiations: Varieties, Contexts, Processes and Social Order. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Strauss, A.L., & Brannen, M.Y.

1999 “Century Organization. Journal of Management Inquiry 8(1): 67-81.

Suddaby, R., Elsbach, K., Greenwood, R., Meyer, J., & Zilber, T.B.

2010 “Organizations and their Institutional Environments – Bringing Meaning, Values and Culture back in: Introduction to the Special Research Forum. Academy of Management Journal 53(6): 1234-1240.

Thornton, P.H.

2004 “Markets from Culture: Institutional logics and Organization Decisions in Higher Education Publishing. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Thornton, P.H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M.

2012 “The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W.

2008 “Institutional logics. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 840, 99-128.

Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Jarvis, O.

2011 “Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model. Organization Science 22(1): 60-80.

Vaerlander, S. Hinds, P., Thomason, B., Pearce, B., & Altman, H.

2016 “Enacting a Constellation of Logics: How Transferred Practices are Recontextualized in a Global Organization. Academy of Management Discoveries.

Van Maanen, J.

1988 “Tales of the Field. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vurro, C., Dacin, T., & Perini, F.

2010 “Institutional Antecedents of Partnering for Social Change: How Institutional Logics Shape Cross-sector Social Partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics 94(Suppl. 1): 39-53.

Waddock, S.

2008 “Building a New Institutional Infrastructure for Corporate Responsibility. Academy of Management Perspectives, 87-108.

Weber, K. & Dacin, M.T.

2011 “The Cultural Construction of Organizational Life: Introduction to the Special Issue. Organization Science 22(2): 287-298.

Yagi, N., & Kleinberg, J.

2011 “Boundary Work: An Interpretive Ethnographic Perspective on Negotiating and Leveraging Cross-cultural Identity. Journal of International Business Studies 42(5): 629-653.

Zilber, T.B.

2012 “The Relevance of Institutional Theory for the Study of Organizational Culture. Journal of Management Inquiry 21, 88-93.