This case study by a pan-African UX research and design agency offers key insights for companies attempting to grow markets and communities in the Global South. It describes exploratory research the agency YUX carried out across four African countries for Wikimedia Foundation, including the foundation’s motivation for focusing on the Global South, the teams and research methodology, the impact of the work, and how differences in positionality sparked debate. Key insights include the relevance of developing non-digital solutions, understanding the specific ways that African participants leverage their Wikimedia work, and addressing the uneven perception of Wikipedia as a neutral source of information. Constructive debate arose because the foundation team had little knowledge of Africa, which obliged the African researchers to be comparative-cultural experts and ethical champions. The case study also explores friction around the fact that, although emic perspectives from Africa had been sought by the foundation, ultimately the more complex solutions the research recommended were not prioritized. However, other recommendations were implemented: the research led Wikimedia Foundation to launch a community-support group dedicated to African Wikipedia volunteers and contributed to leveling up how the foundation supports its volunteer community globally.

STARTING POSITIONS: BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION

The Strategic Importance of Global South Wikimedia Volunteers

In July 2021, YUX – a pan-African research and design agency – was contacted by WMF to carry out a vast exploratory research project across four African countries. The topic of exploration was “volunteering,” and more specifically, uncovering the best practices of successful African volunteer communities. What were volunteers’ motivations and greatest challenges? What would it take to encourage more people to volunteer to organize events for the Foundation? For context, WMF relies on volunteers, sometimes referred to as “Wikimedians,” to organize events called “edit-a-thons,” where people gather to edit Wikipedia articles on a predetermined topic together.1

These edit-a-thons are a great entry point into the Wikimedia community of editors, since they provide training on how to use the Wikipedia platform, as well as a sense of community and group motivation. A lot of articles are started, written and improved during these events, and Wikimedia event organizers are crucial to the encyclopedia’s continued growth and improvement. Building an intentional approach to engaging African and Global South volunteers is at the heart of WMF’s current strategy, because the Foundation is aiming for greater representation in its wikis by 2030. They want to encourage the editing of articles about the Global South, ideally by people from the Global South.

The main challenge WMF faced was that the support they were giving was not as effective in Africa and other Global South geographies as it had been traditionally with European and Western Wikimedians. Because the needs of those volunteers (a typical Wikipedia editor is most often a retired Westerner) were already well documented internally, the research project aimed at exploring how to better adapt the support to African volunteers by learning what was being done locally in existing communities.

The Strategic Importance of a Global Project For YUX

This project was the first of its scope for YUX. At the time the agency was just five years old. Most of the staff was young and African, many were self-taught or had been trained at YUX, and the ratio of juniors to seniors was quite high. Though they had already worked on projects for international organizations and prestigious companies, it had always been on products or services intended for the African continent. This project would be the first global service the team would work on, and as such, it was an endorsement of the quality of what they had achieved. It would have been an exciting challenge for any researcher, but for the YUX team members it meant even more.

Because Wikipedia is a household name, they could tell their family members, and especially their parents, about it. African parents hold high expectations for their children and can have a significant influence on their career decisions, often pointing them in the direction of more traditional prestigious careers, such as medicine, engineering, law, etc. Even if our staff members were trained in sociology or anthropology, joining a “design” agency is a risky move, with many parents doubting their children’s decision. It is important for “YUXies” to “prove” that they made the right choice. Parents have that influence in Africa, even on their adult or young-adult children, and as an agency, YUX has to acknowledge this.

The WMF project was also highly motivating for another reason. The ultimate goal of the project, to encourage more African content written by Africans, spoke directly to the agency’s values. YUX is a pan-African agency committed to using research and design to build the future of the continent and to promoting African design and ownership of content and services. The WMF project was precisely the type of project the agency was founded for.

The Wikimedia Team’s Starting Context

Right from the first meetings, the WMF team was extremely easy to work with and eager to listen. WMF works regularly with their communities and submits projects for their use and evaluation. The needs and challenges in community-building and in using WMF platforms were also well documented internally, but WMF recognized that they did not know the African continent well. Some strong wiki communities, such as those in Ghana and Nigeria, were better known to them, but most of the continent was riddled with behaviors, outputs, requests and challenges they were unfamiliar with and had a hard time building a strategy for.

A study had recently been completed on the existing volunteer-community organizers. It led the Wikimedia Campaigns team to the realization that they didn’t know how other organizations were doing things, particularly in the geographies and languages where their own volunteers were struggling. The design research manager at the time, Ana Chang, pushed for additional research, and because the foundation’s research team was not sufficiently staffed, she pushed for a local partner.

On WMF’s side at the time, there was the senior product manager (the developers and the team designer were in the process of being hired), the design-research manager, a program director, an open-knowledge strategist and the director of community programs. The differences with the YUX team were numerous: age, education, seniority and culture. The WMF staff had attended college, mostly in the US, and although they knew about Global South challenges through their work at the Foundation, their lived experiences did not tend to reflect African realities.

The Black Lives Matter movement had had a strong impact on the Foundation, however, and they chose to seek a partner that would challenge their assumptions. A new DEI framework was being developed and implemented, and the partnership was not only intentional, it was respected. In what felt serendipitous, a big change was happening at WMF at the time: Maryana Iskander was starting as the new CEO. She had worked for 10 years at a South African NGO that relied partly on volunteers. Her knowledge of the continent and her non-technical background signaled a change in strategy. The research was coming at the right time, when a wind of change was blowing, and there were ears ready to listen.

THE RESEARCH APPROACH

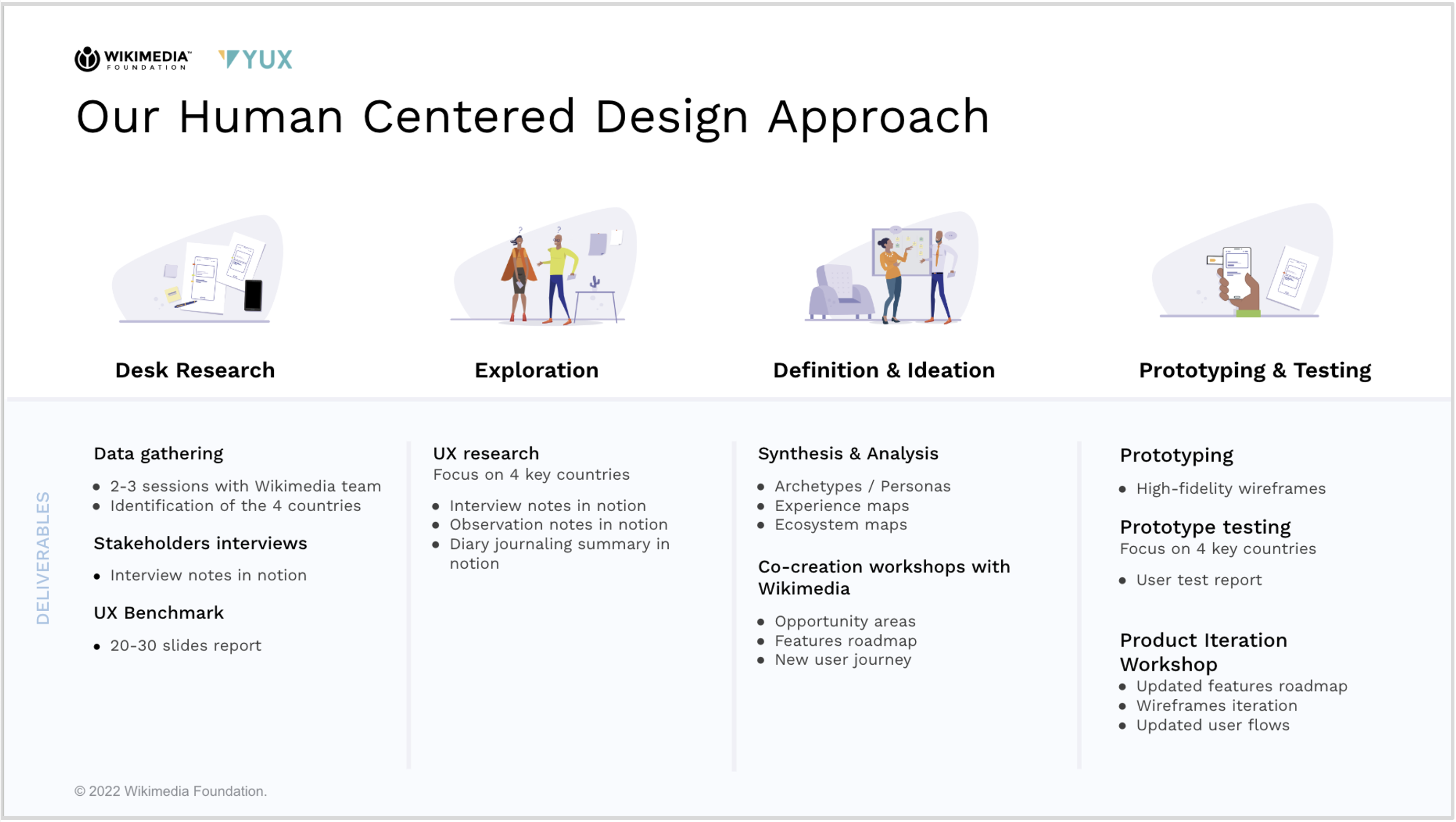

The project had four major phases, with the goal of achieving a comprehensive, on-the-ground, in-situ understanding of community dynamics.

- Desk Research

- Exploration

- Definition and Ideation

- Prototyping & Testing

Desk Research

After the project kickoff, there was a steep learning curve for the agency team to understand the complex world of WMF, and six stakeholder interviews were carried out with people working for the Foundation. Rather than being involved with the technical aspect of the project, most of them were involved with event and campaign organizers, who were in touch with the volunteer groups and were advocating for a shift in approach. Except for one person based in South America, they all lived in the USA, had been at the foundation for several years and were committed to the values of open-source, open knowledge and open access.

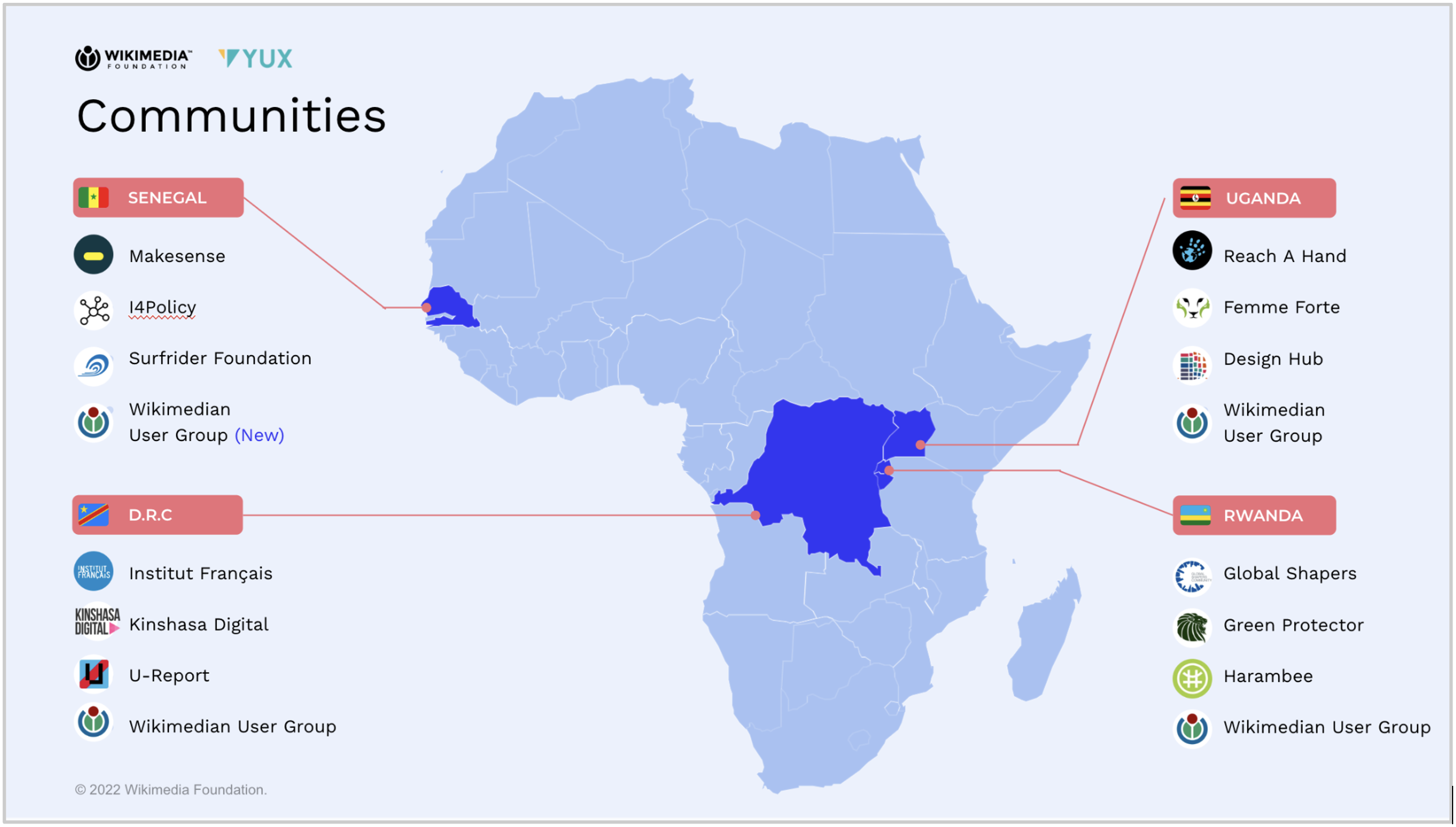

After the interviews, which yielded a lot of insight on what the WMF team expected, already knew and how they wished to leverage the learnings, the next step of the project was to profile the research communities. WMF had not determined exactly which countries they wanted to do research in, so the YUX team built a set of criteria based on the stakeholder interviews. The criteria included practical aspects, such as whether or not there was an active Wikimedia community in the country, and if the YUX team had a presence there. Others were more qualitative: how much did WMF already know about the country? Preference was given to countries they had little knowledge about. Finally, languages spoken, geographical distribution and political contexts were also taken into account. The goal was a balance between French-speaking and English-speaking countries, country sizes and cultural and political dynamics.

The selection process yielded two English-speaking countries: Uganda and Rwanda, and two French-speaking ones: Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Uganda and Rwanda, two East African countries, stood out for different reasons. Rwanda has a very centralized form of government, and Uganda had intense political activism at the time. WMF wanted to explore the effects of those political contexts on activism and volunteering. In the DRC, the project team was curious to explore how country size affects community organizing. Finally, Senegal is a French-speaking West African country, and YUX has its headquarters there, which simplified the research effort. Priority was given to diversity, in order to explore how different contexts impact volunteer-event organizing.

After identifying the countries, the specific communities had to be identified. There were three criteria for selection.2

- They are good at community organizing (size of the community, quality of communication & events, impact)

- They are activist (they aim for some form of social impact)

- Participating may be risky for members (political opposition, personal beliefs, sexual identity or other community identifiers put the participants at some form of risk)

Exploration

The research was organized by country and type of community, with a combination of qualitative research techniques. For all non-Wikimedia communities we conducted two semi-guided interviews (organizers and participants), one immersion at an event and a diary study of the process of organizing an event from the perspective of an organizer. In each Wikimedia community we also conducted two semi-guided interviews and one immersion at an event, but we did not run a diary study, because the focus was on learning from other communities. In total, that added up to forty-four in-depth semi-guided interviews, sixteen immersions and twelve diary studies.

It is interesting to break down the researchers’ profiles, since they impacted the relationships built with participants. As Johnson, Roubert and Semler (2022) point out, “Local researchers provide a critical corrective: they can return to a participant and their daily lives in real time to go deeper into certain stories.” YUX was fully committed to leveraging the benefits of local resources, and made a point of balancing the need for local researchers and research expertise.

Nine researchers were involved with the project: a mix of Senegalese, Beninese, Congolese, Rwandan, Nigerian and Ugandan. The project manager interfacing primarily with WMF was a Franco-American living in Senegal. Most of the team was working directly for the agency, but some were consultants that had been trained at YUX Academy. 3

The semi-guided in person interviews lasted one to two hours in general, and were held at a location chosen by the interviewee. Stricter Covid restrictions forced some interviews to be remote from time to time. Immersions in the community events were a logistical challenge to coincide with the research calendar, because not every community was necessarily scheduling an event within the project timeline. The research timeline had to be extended (from four to six months), but the WMF team was understanding. This also impacted the diary studies, because they had to coincide with an event. The preferred method for them was a WhatsApp group, where a few days before and after the event, the country research lead would send prompts to the event organizer with questions surrounding the event organization and follow up. The goal of these “digital diaries” was to compare them to the other qualitative data collected and build experience maps.

The events the research team attended included training, activist events, member meetings, and annual community meetups. Event duration varied from a few hours to three days. A researcher would be present and observe the rituals, processes and tools each community put into place to create a safe environment for dynamic participation and involvement. The researchers used an observation grid to jot down the event agenda, key moments, level of engagement and number of participants. The reality of this project, though, was that the local researchers had to build relationships with the communities even before the research started. This was only possible because of the networks in which the YUX team were already involved or knowledgeable about because they lived in those countries. The value of local connections is being acknowledged more and more, as Johnson et al. (2022) also emphasize:

Working with local researchers […] allowed us to enter long-established social networks and more rapidly learn about the logics and histories of these networks—knowledge that can often only be gleaned through longer fieldwork engagements.

In our project, this translated into being able to keep in touch with organizers who often had last-minute changes to their events. In Rwanda, for example, one event was pushed back twice. Once because the venue canceled the meeting (but kept the down payment!) and the second time because there wasn’t enough commitment from the organizers, understandably disappointed by the loss of their initial investment.

Not only would those changes have been a nightmare for a non-local researcher, who might not have been able to change their travel plans, but the organizers were initially reluctant to share their misfortune with us. Because our Rwandan team members could meet up with the organizers multiple times, the story eventually came out.

Ideation, Prototyping and Testing

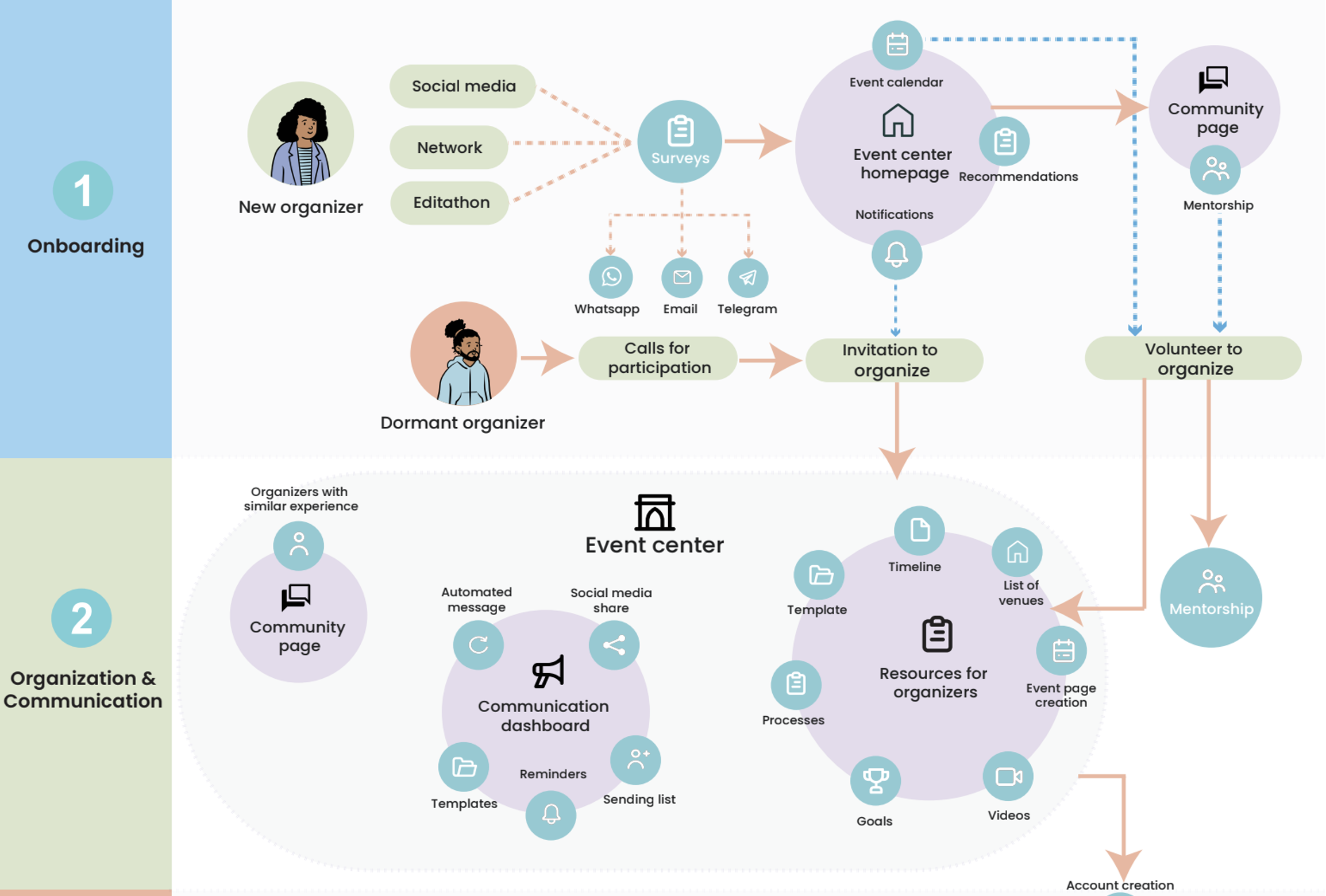

After the research, all the findings were presented as inspiration for a series of workshops with the Campaigns team, to prioritize features the developers and designers would work on in the coming months. This was the Campaigns team’s priority, and in line with their focus on developing digital products. However, the importance of non-digital solutions uncovered during the research also led to a series of workshops focused on rethinking the global experience for volunteer organizers, especially the onboarding process.

In the final phase of the project, YUX designers used the insights about the digital features garnered from the research to design high-fidelity prototypes of a digital Event Center that volunteers could access. The prototypes were then shown (this time remotely) to volunteers to gather feedback over the course of twelve test sessions. A User Journey for an intentional onboarding of new volunteers was also shared for feedback.

NAVIGATING FRICTION TO PRODUCE CHANGE

Contesting Western Assumptions: Learnings That Sparked Debate

Motivations for Volunteering

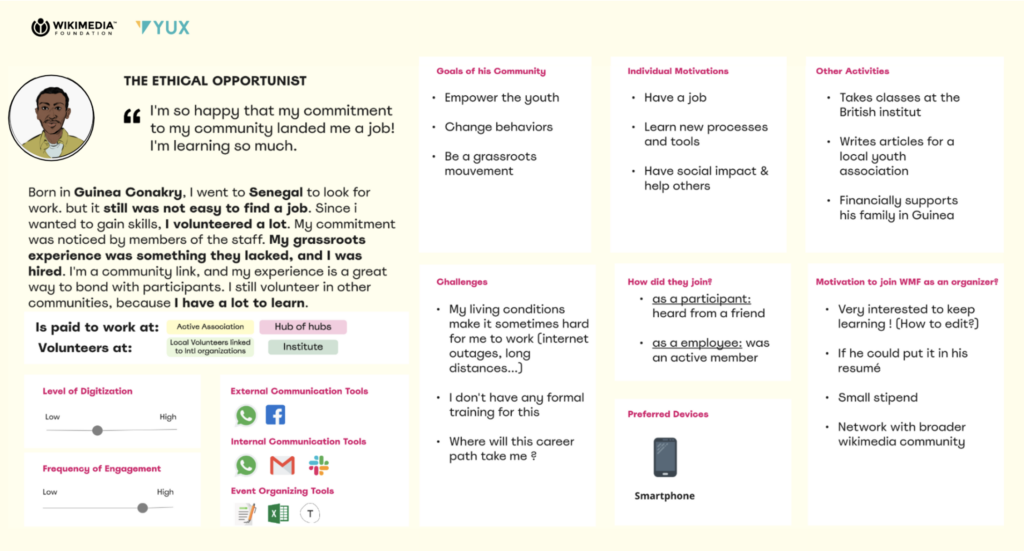

One of our main goals was to identify the motivations of African volunteers to be active members of their communities. This questioned what volunteering should intrinsically be and was an important point of friction. To summarize what Alex Stinson, a Senior Program Strategist at WMF at the time, told the YUX researchers during the stakeholder interviews: typically, most Wikimedian editors have been retired Westerners. They don’t need to work anymore, have lots of time on their hands, and through their career or by sheer commitment, are digitally literate enough to edit Wikipedia. They consider volunteering as a completely altruistic activity, and the sheer satisfaction of having participated is the only reward they seek.

This is not at all the same profile as the volunteers (and potential volunteers) encountered in our research. YUX researchers encapsulated a very typical type of volunteer in the persona of the “ethical opportunist.” This person volunteers both because they want to impact their communities, and because they hope that their volunteer work will help advance their career and maybe even land them a job at the organization they initially were volunteering at.

As one more experienced Ivorian Wikimedia volunteer organizer said, “Obviously [for many people] you need to earn money, as long as there is no money there is no motivation. Some of our members work for the Foundation, that shows to the others that where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

One volunteer we interviewed represented this profile perfectly. Originally from Guinea Conakry, his family had sent him to Dakar, where the schools are better. As a youth and a foreigner, he had very few employment opportunities.4 He was working hard to find his place while also trying to support his family back home.

He studied English at the university, and was curious by nature.

He could not find any paid work but he heard of a Social Entrepreneurship Community that organized community-creativity workshops for social startups. He found that interesting, joined and became a volunteer there.

Through dedication, and because he understood firsthand the hardships local youth faced, he eventually landed a job there as a community-engagement officer. His curiosity and motivation to impact both his community and his own life paid off positively. This dual goal was never seen as mutually exclusive. A memorable quote from this person was “volunteering is an entry point for me to show my skills.”

For many veteran Wikimedians, volunteering was assumed to be completely altruistic. This led to heated debate between YUX and WMF, because the WMF research team knew that some of the current users would defend the position that editing articles and supporting the movement should be a completely selfless action. They were not sure they could start working on a support system that included motivational levers adapted to the needs of young Africans.

Because Wikimedia is an open-source movement, WMF actually has decisional power on very few things, and forcefully changing features could put the existing community of Wikimedians in an antagonistic posture.5 How could this change in approach be communicated? Would it spur tension between wikis?

Our job was to highlight just how important that type of potential volunteer was, and how much WMF needed to acknowledge and act upon that knowledge if they were really committed to inclusiveness. People fitting the “Ethical Opportunist” persona are among the most common volunteers to be found in Africa, and designing a win-win proposition that would be highly motivating and beneficial could yield terrific results. As a result, we created an onboarding journey towards volunteering that WMF could leverage through training, networking, recognition, and certifications. During the definition and ideation phase, YUX researchers were able to contextualize and remind the WMF team about the importance of keeping those motivators in mind.

Effectiveness of Digital Solutions

The second main point of friction was the Campaign team’s strong focus on digital solutions. WMF is a tech-first company. 6 The type of insights they initially expected the research to yield were about which digital tools – such as sign-up options, event-page layout, or sharing features – African volunteers might find most helpful. The department owning the research was the newly created Campaigns team, mostly composed of technical profiles, developers, product owners and UX designers. They wanted research recommendations to inform the design of digital tools for all volunteers, not just those in the Global South.

Without generalizing for the whole continent, African countries often have poor internet accessibility for their populations, whether because of the pricing or the quality of the networks. In many areas, young people are also digitally low literate, and even when they are not, event organizing is a paramount relationship-based activity. The tech-first approach that could work for editors does not apply in the same way for event organizing.

In the communities we observed, interpersonal relations between participants and organizers were the most important success criteria for an event. In the DRC, for example, people would participate because they knew the person organizing the event, at least by reputation. Because there is a lot of instability in DRC, trust and reassurance, including being able to contact an organizer, especially for the type of selfless volunteering the wiki communities have to offer, was very important.

In every country, sharing a phone number was an essential requirement, if only to be able to contact someone for instructions on how to find the venue (since street addresses don’t always exist). Community- and event-organizing details were shared through apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram. But for WMF, which is committed to anonymity, collecting this type of personal data is not possible.

One major conclusion of the research was that some of the most potent ways to better support African communities would not be digital. The volunteer organizers had already found digital solutions that worked for them (using Google registration forms that allowed them to gather the necessary data, such as phone numbers, to communicate with participants.) What they really needed was a support system that understood their particular context.

We noticed that French-speaking African Wikimedians had an informal peer-to-peer support system through social media. Mentorship would happen fortuitously through twitter posts that connected people. The Cameroonian community, for example, had supported the Ivorians and Senegalese on organizing events, and simply learning how to use the platform. That kind of support was not easy to find directly through WMF.

Part of the reason for that is that in WMF’s construct, people are readers first, then they become editors. Those who become volunteers are the most passionate ones, and they already know how to use the platform. That is not the case in Africa, where the motivation to volunteer is both more idealistic (promoting your culture) and more opportunistic. In fact, many of the African organizers were not at all expert at editing!

The current WMF community had few resources to help in that regard, and even fewer that understood the African volunteer’s context well enough to make meaningful connections and give pertinent advice. So we recommended creating a regional group for Global South communities. The team would be composed of paid staff, focusing on helping to promote local user-group events, defining best practices for sources, training local volunteers and representing the user groups at commissions. WMF is currently piloting this recommendation, in a project called “The Africa Growth Project” as documented in an email with the subject matter “Africa Growth Project Pilot: Invitation for Input” sent on June 26, 2023 to the African Wikimedians email list:

“The project seeks to enhance already existing community efforts by creating a more effective online learning component, which would allow in-person efforts to focus on already-engaged newbies who have obtained a solid foundation in Wikipedia policies and collaboration norms, maximizing the return on investment of human volunteer effort. The hypothesis guiding this experiment is that providing high-quality training to new and existing Wikimedians covering the basics of contribution to Wikimedia (including introducing the many ways to contribute beyond article writing) can double the retention rates of active editors in the region.”

It is still too early at the moment of this case study publication to share the results, but the community’s enthusiasm for and engagement with the pilot have already been extremely high.

Perceptions of Wikipedia as a “Neutral” Source of Information

Encouraging the creation of African content on Wikipedia seemed like a great initiative from all our points of views, but as we became more knowledgeable about the article-approval process, and as we heard more Africans’ opinions about Wikipedia, this initiative became a third source of friction.

Wikis are organized by language. There is a French wiki, an English wiki, a Yoruba wiki (you will notice if you switch languages of an article that the layout of pages is different, this is because each language wiki community can decide for itself!). Admins and robots verify the validity of articles and article contents, and this is decided by the community of that particular language. For example, all articles in French are validated by the French wiki… mostly by people based in France! So if an Ivorian editor creates an article in French about a local artist, a French moderator may not consider the artist “important” enough to have an article on Wikipedia. Yet what authority should a French person have on upcoming Ivorian graffiti artists? The issues with that situation are compounded by the encyclopedia’s requirements, such as sources and references, which are often hard to find for the buzzing, growing, ever-evolving abundance of activities in African countries. This digital control of voices and content sparked passionate debate within the team, some seeing Wikipedia as a Western tool of thought domination because of its requirements and validation format.

While reading Wikipedia was not our main research focus, we did get some interesting learnings. Many people mentioned, for example, that they did not know they could edit Wikipedia, and that certain specific topics, like pages for politicians, had biased information. Cultural agendas, consciously or not, transpire through writing, however neutral the author is trying to be. Because the editing and volunteering process was ill-adapted to the Global South, many Africans were disappointed, if not frustrated, by the content of articles about Africa on the platform. YUX’s perspective was that our work could help mend that gap, even though things would not change overnight.

Some wiki communities, like the Yoruba and Swahili ones, are thriving and making the platform their own. The Ghanaians, even though they contribute to the English wiki, have enough momentum in their movement that they are growing their agency. WMF is aware of the challenges of structuring wikis by language, and supporting the volunteer organizers is one initiative to strengthen local groups, and help grow their influence. Ultimately because it is an open-source platform, when communities mobilize they have greater impact. So we emerged from the process with a new sense of the importance of strengthening local volunteer communities. But changes need to happen at every level of the organization so that the effort is not disproportionately placed on the volunteers.

The Burden of The Global South Researcher: Being Comparative Cultural Experts and Ethical Champions

Someone born and raised in the West, but who has lived in an African country for almost a decade, is aware of and able to explain many of the differences between the two places. When the African YUX team members started synthesizing and analyzing the content collected, the Western project manager from YUX supervising the project noticed an interesting trend. Her African colleagues were not emphasizing key learnings that she knew WMF would find particularly illuminating. Because of their emic perspective on the content, some of the information was too obvious, too normal for them.

One example was the absence of street addresses in most African cities, which made event details and registration features a challenge. In all four countries where the research took place, and particularly in DRC, participants mentioned the importance of being able to call event organizers to get directions for the exact venue location. This was also observed during an immersion in Senegal, where the community HQ had recently moved to a residential area where the streets were still sand and not asphalt. The event started almost an hour late because everyone had to call the organizer, who was constantly on the phone giving directions, sharing landmarks and detailed instructions for the last few hundred yards. Though this challenge was identified, the African researchers did not specifically point out that event venues often don’t have precise street addresses. The researchers had grown up in an environment where addresses are not a regular feature (at least not the Western number/street name/city/ZIP code model). It would be as if an American researcher mentioned in their analysis that someone lived somewhere that had an address. Superfluous.

So we realized that not only did the African researchers need to be good researchers, they were also expected to know what gaps in knowledge the client had. This is a common requirement for any project if you intend your research to be useful, but at the scale of a whole culture, it takes on a different scope. It puts added pressure on local researchers, who suddenly need to become experts in two cultures instead of “just” being good at research. But it can be a real burden, because the cost of acquiring that knowledge is quite high. Studying and traveling in the West, let alone working abroad, is not available to most people from the Global South, of course. So that requirement creates a barrier to entry into the field, making it harder for local resources to be acknowledged for their expertise.

In addition, local researchers may also find themselves in a position where their own values and Western client expectations are in conflict. One such situation occurred during the recruitment process.7 Our initial desk research had identified an interesting community in Uganda, but they did not wish to participate in the project or give information about their processes and systems to a Western organization. The organizer’s answer was “We don’t want to make contributions to information available to the Global North because that’s what we always do. I am not interested and neither is my community.”

That was quite early in the project, and led to some great conversations internally at YUX. How could the “low hanging” advantages of local resources, such as proximity with the populations, knowledge of context, language, access, even environmental concerns (fewer plane flights) not be diverted to yet more exploitation and more efficient “extraction” of information by the West? Are we avoiding “feeding” northern expertise just by working with more inclusive research teams or, on the contrary, are we making that process even more efficient? As design thinkers and HCD practitioners use ethnography, are we perpetuating exploitative practices through lack of hindsight? Hasbrouck (2015) pinpointed the “ethnography-as-a-tool’ perspective in the design thinking process:

The ways in which design thinking is often integrated within these organizations —structurally deployed with an ‘ethnography-as-tool’ perspective—aligns quite comfortably with the ethnographic gaze of early anthropology. From this view, the design researcher’s position in the field of consumers is often presumed to be central, authoritative, and unquestionable. Upon return, the design researcher is expected to bring back and represent the voice of the target consumers for the design team—whose perspectives ultimately ‘really’ count. You can see that this is a dynamic within which it’s all too easy to replace ‘natives’ or ‘colonial subjects’ with ‘consumers’ or ‘users.’

At YUX, we believe that local researchers naturally promote and amplify the positive values of ethnographic thinking, while minimizing if not erasing the “gaze outward.” When the person you are interviewing could be your little sister or your neighbor, there is no otherness. Diary studies turned into conversations, without the gravitas of formality, and with candid and down-to-earth exchanges instead.

One example of this was when an organizer in Senegal turned out to be writing to a local researcher in a diary-study WhatsApp conversation… from his hospital bed! He had had a bout of malaria in the days leading up to the event and was being treated for it. Although he was extremely tired, he actually appreciated that we were getting in touch and checking in on him. We knew what hospital he was in, because we had been there. We were able to cheer him up by sharing stories about it. We stayed in touch for quite some time after the official “research phase” was over, and some later conversations deepened and nuanced our understanding, and improved the quality of our recommendations.In this way, with local teams, research becomes ongoing, deeper and richer. The human stories emerge with greater arcs. Others are not just “others,” they are real people. But to achieve this, local researchers should not just be tools for improving access. If we are not contributing to the analysis and recommendations, then it is exploitation. And if we are contributing, then we need to have enough influence and respect for our contributions to be valued. WMF was a great partner in this aspect, and consolidated our budding team’s determination to be the voice of their people.

Achieving Impact: Productive Friction

Decision-Making Power Remains in the Global North

Tensions in this study stemmed from the differences in backgrounds and positionality between the WMF team and the local African researchers. Because every team member’s unique background informed what they noticed and how they interpreted the research, new pathways were possible that would not have emerged otherwise. We might call these tensions productive friction. Both teams had a positive attitude and recognized the different outlooks, and who held expertise on what. The WMF team respected the conversations and could not have been a better partner. This being said, it did not mean that certain key recommendations were followed through or prioritized as the YUX researchers advised, which is a testament to the difficulty of initiating change, and, as the design anthropologist Dori Tunstall notes, representation has to be at all levels of an organization, with more than a token individual but a cluster of people who are committed to promote change (Tunstall 2023). For us from the African research team, the amount of confidence in ourselves to voice our opinions and conclusions when we knew they would challenge or potentially make a project pivot had to be very high, and honestly was not always easy to find.

Through a combination of the WMF team’s willingness to listen, and our motivation to represent our communities, the conversation that needed to happen happened. But the final limit remained: the decision-making capacity remained in the hands of the client, and some features without which African volunteers would practically not be able to function were deprioritized because they were too complicated to implement at the time.

The messaging options mentioned earlier are a case in point. Accommodating volunteer organizers’ need to collect phone numbers would have been a great opportunity to demonstrate willingness to go the extra mile for inclusion. But because the WMF respects rigorous anonymity protocols, this was a complex issue. The Campaigns team was a new team trying to ship a registration process quickly, so finding a solution for an on-the-ground reality of African community organizing was deprioritized. This highlighted a limit between wanting to serve the Global South, but not being willing to adapt to the Global Souths’ practices when it required more effort than initially estimated. Ultimately, though the YUX researchers were frustrated, the WMF Campaigns did understand this feature was important and hopefully it will be addressed once the team has shipped simpler features and accessed more funding. Having the international team so intimately embedded in the product design process made these conversations unavoidable, which was what the Foundation was looking for. As Hasbrouck (2019) put it:

Contemporary ethnographic thinking turns the gaze back on itself, forcing organizations and practitioners to come to terms with their own histories and orthodoxies, and to face how those realistically impact their capacity, or inclination, to innovate.

Any change in the behemoth-like Wikimedia ecosystem is a huge endeavor, requiring community support. Creating the content, making it accessible and digestible, and sharing stories are among the most efficient ways to encourage change.

Core Changes in the WMF’s Support to Volunteer Organizers

The biggest impact of our work was in the adoption of a new holistic approach to the volunteer-community-organizer experience, based on the motivations of profiles such as The Ethical Opportunist. In addition to the Africa Growth Project mentioned earlier, the WMF Campaigns team is also leveling up how WMF supports its volunteer community globally, with an “Organizer Lab” for all Wikimedians being piloted within a year of the research.

Four of the Lab’s five pillars directly reflect recommendations from our study: Mentorship, Peer-to-Peer Support, Training and Resources. Although this lab is the culmination of multiple studies and internal advocacy for organizers, such as the 2019 Organizer Study, the African organizers’ perspective confirmed and reinforced the necessity for it. Here is how WMF communicated about the launch of this program to the Wikimedia community:

We are also designing the course based on several other indicators beyond our team’s work: the Movement Organizers research and other research we have been doing as part of the Campaign Product process have emphasized how hard it is for new organizers to understand how to get more involved in the movement.8

YUX has been working for WMF on several other research projects, always with an African focus. Mike Raish, from the Core team, shared with us that features such as voice-to-text/text-to-voice are now being seriously considered thanks to the advocacy work of our research findings and recommendations. Voice-to-text/text-to-voice would be extremely helpful in the African context because of the high use of mobile interfaces, low literacy rates and the fact that many speakers of African languages do not write in their native tongue. “Many people at the Foundation have taken that up, and it’s a real thing.”

Growth at YUX

The YUX team also grew through this project. We were still a young team at the time, and navigating the path of growth for our maturing agency was akin to performing a delicate balancing act. We aimed to expand rapidly, but we were mindful not to push ourselves so hard that we might crumble under the pressure, or betray our values. It was all about finding the right rhythm and balance, between internal and external friction in our journey towards growth.

WMF’s vast repository of information, accumulated over years of global projects, was an invaluable resource. On the other hand, our junior researchers found themselves grappling with a flood of new terms and concepts, often needing to reframe and redefine them based on Wikimedia’s unique definitions. The learning curve was steep. From navigating a bilingual team to the logistics of doing research in four different countries, YUX redesigned its internal structure thanks to this challenge.

One major output was the creation of the Research Ops position at YUX. We also introduced a new feature within our panel product, LOOKA, designed specifically to facilitate participant-recruitment-and-compensation management seamlessly. This feature alleviated the logistical complexities associated with research operations. These adaptations not only improved the efficiency of our research operations but also empowered our researchers to concentrate more fully on their primary roles, enhancing the quality of our research outcomes.

Ultimately we will grow and become more professional, but never sacrifice our voices. Recently, a partner from the WMF sent our Product Research team the best compliment designers could get: “The team that requested the report liked it, they are making decisions based on it, and it is affecting the interface that millions of people will be using.” From Africa, to the world.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Camille Kramer-Courbariaux is a UX researcher and co-founder of YUX. Her responsibilities include strategic leadership and program coordination. She is the focal point for the YUX Academy, and is engaged in making HCD a reality for African organizations and companies. She is Franco-American and has lived in Dakar, Senegal since 2017. Contact her at: camille@yux.design

Sasha E.N.A Ofori is a UX researcher at YUX. She is based in Accra Ghana, where she employs various HCD methodologies to create innovative services and products for our partners in the health, education and agriculture space for different UX-related projects. She is passionate about growing awareness for mental health in Africa. Contact her at: sasha@yux.design

Kalama Hafisou is a UX researcher at YUX. He has worked with clients in the Fintech, Global Health and Market spaces and is operational in designing user-experience strategies. He is Beninese and has lived in multiple African countries, his current base is in Accra, Ghana. Contact him at: kalama@yux.design

NOTES

This project would not have been possible without WMF’s 2030 goal for better representativity in Wikipedia articles, and the amazing and passionate people who work there and are committed to making this vision a reality. Thank you Ana Chang for having sought out local researchers, Gabriel Escalante for your willingness to share your expertise, and the whole Campaigns team who were amazing to work with. Thank you Rita Denny for your patience and the great resources you shared with us. And finally thank you Yann Lebeux and the whole YUX team for being such amazing people to work with.

1. In the Wikimedia sphere, editing includes both creating entries and modifying existing ones.

2. YUX provided shortlists, and the WMF Campaigns team voted for the top three communities for each country. If a community did not respond or refused to participate, the community with the next highest number of votes, or a similar one in the country, was contacted. In each country a Wikimedia user group was also included, for a total of sixteen communities.

3. A training program for African designers and researchers founded by the YUX agency.

4. Approximately 61% of Senegalese are under 24 years old (40% under 14) and with the formal sector accounting for only 3% to 4% of the job market, many are forced towards the informal sector. For university graduates the options are very scarce.

5. Although the Wikimedia Foundation is the “client”, they are not the ultimate decision-makers for all things wiki-related. Because it is an open source community, in reality WMF has little power to decide what the movement does. Even if they try to impose a change, users can refuse it, or create a version they prefer. So the issue of adoption by the community is primordial.

6. Decisions are made by technical teams based on developers’ understanding of user needs, rather than a human-centered approach focusing on understanding underlying issues before implementing change.

7. Recruiting was a challenge because WMF had no previous relations or contacts within the communities and couldn’t help with introductions. Instead we were able to leverage being local. All in all, out of the twelve initial non-Wikimedia communities reached out to, two never responded, and one decided to withhold from participating in the research.

8. All information about the Wikimedia Organizer Lab led by the Campaigns team is available here: https://meta.Wikimedia.org/wiki/Campaigns/Organizer_Lab

REFERENCES CITED

Tunstall, Dori. 2023. Decolonizing Design. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Johnson, Tracy Pilar, Roubert, Chloé and Micki Semler. 2022. “Shifting Design, Sharing Power.” Anthropology News, April 28, 2022. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/shifting-design-sharing-power/

Hasbrouck Jay. 2015. “Beyond the toolbox: what ethnographic thinking can offer.” EPIC Perspectives. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.epicpeople.org/beyond-the-toolbox-what-ethnographic-thinking-can-offer/

Campaigns/ Organizer lab Discussion Page. Meta-Wikimedia.org. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://meta.Wikimedia.org/wiki/Campaigns/Organizer_Lab