Researchers across all industries have endured periods in which their business value was questioned. In industry terms, research is a cost center, so throughout economic downturns, research has often felt the brunt of company downsizings. This held true for researchers in tech during recent (and in some cases ongoing) layoffs. We have been confronted with mounting pressure to justify our existence by (yet again) proving our value.

What does it mean for us to subscribe to the belief that we can and should measure impact? What are the risks and potential rewards?

Efforts to measure research impact

In our perpetual quest to make our impact visible through quantitative business and productivity metrics, multiple methods have cropped up, each with their own set of pros and cons. Some are:

- Tracking citations as the amount of mindshare we have influenced.

- Tracking decision making that can be attributed to our work.

- Tracking the successes of our stakeholders’ projects and tying our work to valuable metric changes (sign-ups, reduced call center calls, engagement, etc.)

- Tracking the number of our recommendations that have been acted on.

- Tracking the resources saved by preventing work on a poorly received concept.

There is no shortage of ways that we have attempted to demonstrate impact. But what are the consequences when we play this game with our stakeholders and with the business?

Dissecting the drive to measure impact

It’s imperative we dissect the dialogue of impact measurement. We must distinguish these two strains of thought. In some cases, the discussion of impact concerns the worth of the entire discipline – does research as a practice provide value and should it exist in a business at all? In other cases, “impact” debates are about ethical and effective ways to measure an individual researcher’s “impact”, now considered a means to measure performance.

Failing to distinguish between these aspects of impact can transform the operational issue of individual performance tracking into the existential challenge of proving the entire discipline’s worth within an organization, a weight that no individual researcher should have to carry.

Potential drawbacks of impact measurement

Ultimately, “measuring impact” is a set of practices situated within a system. What does it mean for us to take part in it? We need to ask if we truly believe that measuring impact within the existing system will evolve and grow our discipline – or simply continue to devalue us.

Right now we’re in a defensive position: with the contraction of research in some key industries, it’s difficult to look at long term growth when the short term demand feels like we must simply prove our right to exist. But in the struggle to quantify our worth, are we simply encouraging a method to cap our worth?

Often our efforts to track impact are born of a combination of organizational pressure and a proactive effort to answer our critics. Pragmatists are eager to apply our tools and skills to the task of proving we’re needed. Skeptics wonder if by willingly measuring our impact we’re fronting up to a Kangaroo Court and expecting a fair trial.

The word “impact” is biased towards action, which is problematic in several ways. It reflects the belief that action is the epitome of achievement, underscored by organizational goals such as “shipping velocity”. Underlying this is the devaluation of well-thought-out, larger scope projects that could have a more sustainable business impact. There may be a perception that larger, longer-term research programs do not deliver impact in the way a business needs. The bias towards action rewards speed while simultaneously devaluing collaboration.

As highlighted by Steve Hillenius in an EPIC2024 Learning & Networking Week panel discussion, we need to examine how the pressure of impact measurement can affect how we define our projects. Shaping our craft to fit impact measurement can limit project scope to achieve more measurable outcomes more quickly. It may compress project horizons and encourage short-term thinking. How many projects did you affect? How many decisions did you influence in a 3 month period?

Larger, longer term projects will inherently become riskier, if we consider risk as no immediate business metric change, thus placing budget, authority and jobs at risk.

If we look to other industries for inspiration, we can see examples where the value of research is viewed within a longer horizon, not per individual research study. In the pharmaceutical development industry, 90% of drugs that go into clinical trials fail to make it to market.1 Despite this low success rate, companies continue to invest in R&D due to high potential rewards of a drug’s success. They apply rigorous testing and regulatory procedures to ensure safety & efficacy, understanding that failure is an inherent part of the innovation process.

The pursuit of demonstrating impact and ROI of research has existed in older industries, like industrial research, for many years. One 1969 article states only 75% of projects could find technical success ,2 further demonstrating an acknowledged variable success rate. Research was executed with the mindset that a single study had promise but no guarantee of results that could affect the bottom line. Research was still encouraged in for-profit companies because a few would transform everything (e.g., transistors, semiconductors, lasers, color TV) and create enormous amounts of value for the business.

So, the real concern is, does today’s focus on immediate impact compress the field to low risk/low reward results and reduce the likelihood that we make these game-changing discoveries? Counterintuitively, will impact tracking reduce the impact of our work in the long run?

The portfolio approach and individual performance at odds

Perhaps the issue of judging each individual research project on impact can be solved by a portfolio approach—then research as a function can prove its impact over time by the average success of a large series of projects. Varying levels of success and “impact” per project will be acceptable. This would still encourage “riskier” exploration of unknown subject areas that we believe, but are not certain, will yield business impact. Some projects will incrementally improve our products, some could introduce entirely new greenfield opportunities and some may not produce any business impact due to unforeseen reasons. Each result would be acceptable as long as the research was planned in good-faith belief of potential business impact.

The tension in this perspective then lies in the ethical measurement of researcher performance via impact measurement. If there’s a known fail rate, should a researcher who committed to a research project that was scrapped due to unforeseen circumstances (eg. strategic changes or macroeconomic events) receive a lower performance rating?

To move forward with a portfolio perspective for impact measurement, we need to reconcile the individual performance system to allow affordances for when good research does not produce impact. For years, different industries have tried to define the rates of return on research and development—and many acknowledge that despite best efforts, there are multiple elements outside of research that affect its ability to produce business impact, including “that uncertainty can be ignored”. 3

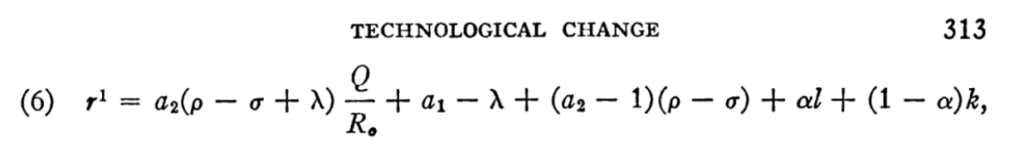

An attempt to quantify the marginal rate of return from the extra expenditure in 1965 3 on R and D from the American Economic Review. The author states to use with caution for multiple reasons, including that it assumes uncertainty can be ignored.

To build affordances into a research impact tracking system is to acknowledge what Erika Hall highlighted during the panel discussion, that many steps outside of research need to occur to bring a feature to life. Many factors are out of our control including but not limited to organizational changes, misalignment, personnel changes, understaffing, new technologies and strategy shifts. Building this into an impact tracking system will also allow researchers the mental safety to fully pursue research that they believe may have the greatest possible impact.

What we’re trying at Atlassian

At Atlassian, we assumed our impact was self-evident through the value we delivered to cross-functional partners. However, we learned that the specific ways we deliver value were less legible to senior leadership and less easily articulated using common, industry-standard frameworks like key metrics and KRs. We have begun to experiment with impact tracking despite justifiable and healthy skepticism to wrest back control of the narrative of our contribution.

We are learning as a discipline to connect our work to business outcomes in more explicit, quantifiable and transparent ways. While this topic has cropped up before, we may have just approached it differently previously. We know there are risks, but believe these are outweighed by the risk of refusing to engage. By engaging we can (hopefully) help to shape the direction and evolution of the field in ways that won’t be possible if we were to abstain.

Thus, we’re applying years of learnings related to agile software development metrics, optimization, and ways of working to track the actioning of our recommendations. We are also leveraging our very own project management software.

Unsurprisingly, our impact tracking system had a mixed reception from researchers. Some have gladly taken to it, but others have expressed hesitation and concern over yet another set of administrative tasks.

We are currently working through two key issues. First is building the affordances mentioned above into our research impact tracking system. We have a process whereby researchers follow-up months afterwards and can mark whether the work was actioned on, what impact it had or if it was not actioned on and they can make note of why it wasn’t actioned on.

The second issue we’re tackling is alignment with business leaders on the definition of research impact. We have a wide variety of researchers—market researchers, design researchers and ethnographic researchers. We’ve created an initial draft of a taxonomy of impact that attempts to reflect the breadth of impact of our teams. It includes such themed categories as business value (eg. contributions to Level 1 or 2 OKRs), cost avoidance (eg. decisions to not pursue a direction), or reduced operational costs (eg. vendor consolidation). Researchers have walked business leadership through the taxonomy in collaborative sessions, obtaining feedback and further refining.

Through these efforts, we hope to address the concerns of our individual researchers while also speaking the language of the business.

We apply the build, test, learn loop to all our internal processes and have a healthy culture of experimentation. Despite some trepidation, our researchers understand that this is a first attempt that will be re-evaluated, with opportunities for improvement.

As this system develops, we hope that the aggregation of incremental project impact will demonstrate the value of research via a portfolio approach. We also hope researchers will leverage it to their benefit. Research project tracking not only creates a system of accountability for researchers, but for our stakeholders and partner organizations. It creates a trail of detailed documentation. For instance, if a researcher notices via project tracking that projects with a particular partner team don’t get actioned–they have the documentation to petition to shift focus to other, more receptive teams.

The hope is that the method of impact tracking is more regulatory—a means of keeping track of the outcomes of our work, rather than a reward and punishment system.

Shaping the future

Research in business has always evolved along with changes in the business environment. This is a time of intense experimentation as research has been devalued in the eyes of some business leaders. Impact tracking, at some organizations, will be a large part of this experimentation. Will these unwelcome conditions actually push us to create valuable new approaches? What practices should we look to discard? Here at Atlassian, we will closely monitor what is effective in demonstrating our value to the business while also moving our craft forward. With the correct affordances, we believe the discussion of impact tracking is not about the extinction of our practice, but the evolution.

Many thanks to Sarah Stewart, Steve Hillenius, Sharon Dowsett and Gillian Bowan for their valuable contributions to this article.

Atlassian is an EPIC2024 Platinum sponsor. EPIC is a nonprofit organization, conference, and community, and sponsors support programming that is developed by independent committees members and invites diverse, critical perspectives.

- Sun, D., Gao, W. & Hu, H. (2022). Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?

Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 12(7): 3049–3062, doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.002 ↩︎ - Mansfield, E. (1969). Industrial research and development: Characteristics, costs and diffusion of

results. The American Economic Review, 59(2): 65-71, https://www-jstor-

org.ezproxy.sfpl.org/stable/1823654?seq=1 ↩︎ - Mansfield, E. (1965). Rates of Return from Industrial Research and Development. The American Economic Review, 55(1/2): 310-322, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1816272 ↩︎

- Mansfield, E. (1965). Rates of Return from Industrial Research and Development. The American Economic Review, 55(1/2): 310-322, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1816272 ↩︎

0 Comments