This is a piece about certain types of objects. Those objects are models.

I want to suggest that models are objects that are central to the various practices in which EPIC People are engaged for three reasons. Firstly, they help manage situations of uncertainty. Second, they are tools for communications. Third, they represent technologies of enchantment.

Let’s take uncertainty first. Like it or not, life is full of uncertainty.

“Given the inherent ambiguity of all reality and the nagging suspicion that we always exist on the edge of existential chaos, objects work to hold meanings more or less still, solid, and accessible to others as well as to one’s self” (Molotch 2003: 11).

The lives of individuals and businesses are plagued by knowledge about what may be and what might become. Both individuals and businesses are always on the look out for anchors in a world of vertigo inducing uncertainty and ambiguity. Models are just such anchors. Providing anchors in an uncertain world is a good business to be in.

Models are Good to Think about Complexity

In his EPIC 2012 keynote, Hugh Dubberley argued that “a model is an idea about how part of the world works. Representing the idea aids its refinement”.

But models are more than mere representations. As Dubberley suggested, we use models to make sense of and think through the world. A model can help us break down the constituent elements in a phenomenon – or group of phenomena – which then makes it easier to think about their inter-relationships.

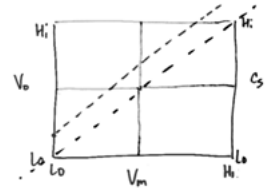

Models bring simplicity and clarity to complex situations. Think of that stalwart of all manner of consultants, the 2 x 2 matrix, which allows to plot positions and relationships.

Models are labour-saving devices which reduce the intellectual overheads associated with an activity. Models are good to think with – they allow us to see relationships between things that were previously hidden.

As ‘sense-makers’ our use of models is typically to reduce that cognitive burden for others: we’ve thought so others don’t have to.

Models are Good to Communicate with

Yet beyond being (cognitive) labour saving devices models have another obvious virtue. They provide a shared intellectual scaffolding: a common ground upon which people can interact and engage. In that sense models have communicative virtuosity – they are good to talk with. They allow ideas to be shared.

Having listed some of many virtues of models it’s worth remembering two other features of models.

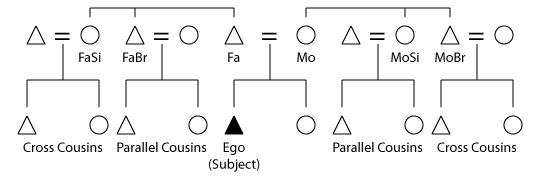

First, models are idealized representations. They are descriptions of the world which are prone to ignore inconsistencies between ‘typical’ behaviours and what occurs in practice. For example, normal kinship diagrams ignore the messy interplay between ‘rules’, preferences and actual practices.

Second, our models are not neutral. They embody and represent theories and ways of making sense of the world. In creating models we make theoretically informed choices.

In that sense, models are performative. They don’t just provide a description of the world – they change it. Michael Porter’s Five forces model has not just described the nature of corporate existence for over three decades or more. It has actively driven corporate strategic decision making.

Models as Technologies of Enchantment

They may not always take a physical form but models are still tools or technologies. As anthropologist Alfred Gell would have it, models are technologies of enchantment: they are tools which “allow us to bridge the gap between ‘a set of given elements and a goal-state which is to be realized by making use of those elements’ (1988).

Put another way, models have an instrumental value in translating ‘what is’ to ‘what might be’.

Readers of this post will all have their favourite models who lineage can be traced back through the various lines of descent in the disciplines and sub-disciplines that make up the EPIC community.

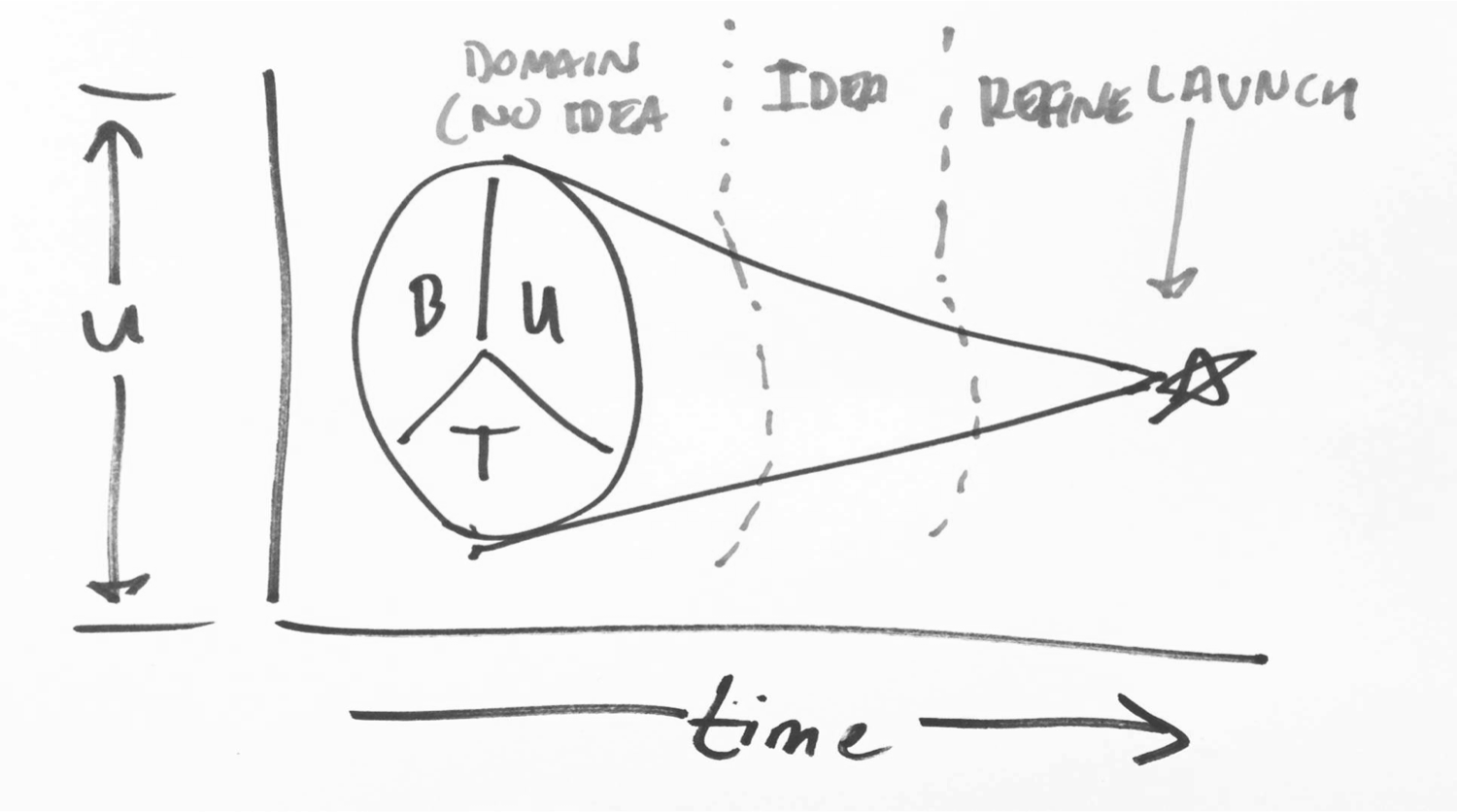

Rick Robinson’s e-Lab bequeathed us the ‘experience model’, Intel had its BUT model (Business, User, Technology):

but that’s been upended by thinking about flux and has given way to this:

As the title of Anderson, Barnett and Salvadors’s paper suggested, models are in motion as the world itself changes.

The implication of Hugh Dubberley’s talk was that by finding ways to describe the world models bring order and manageability to it. And bringing order to a complex and uncertain world is a valuable thing to do. It’s often what consultants are paid for.

The Million Dollar Model

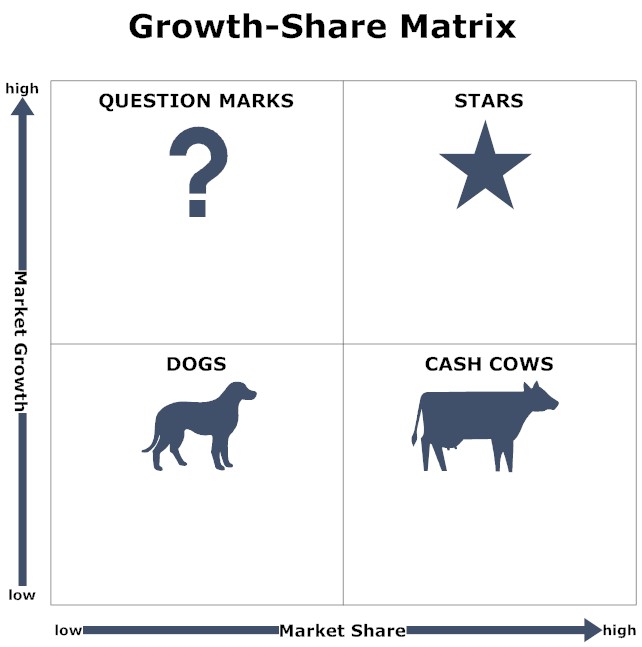

The brief history of a famous model is an illuminating example of this power and value. The Growth Share matrix was developed in 1970, by Boston Consulting Group. The matrix grew of out work to understand Union Carbide’s business, portfolio and the structure of the chemicals industry. BCG was attempting to transform the enormous complexity of the industry into a dashboard that would allow an executive to understand which of their lines, products or brands were growing relative to the growth of the market at a glance.

In its simplest form, the dashboard could be boiled down to 4 figures on a graph: stars (high market share business in fast growing markets), cash cows (high share businesses in slow-growing markets), dogs (low share businesses in low growth markets) and question markets (business in high growth markets with small shares relative to competitors).

The value of this apparently simply model quickly became apparent:

“When a client’s actual business units were platted on the matrix the result was often what certain consultants – most of them at Bain & Company – later came to call ‘the million-dollar slide’: a single image that captured and conveyed so much information about a company’s strategic situation that by itself , it was worth a million dollars in consulting fees” (Kiechel 2010, 65),

This matrix has its detractors but it lives on. It has earned a place at the heart of the management consultant’s pantheon of models.

Models as Technologies of Enchantment

Brian Moeran’s EPIC 2014 did a lovely job of talking about advertising as a form of magic. He made the observation, after Malinowski, that magic is rarely found in situations of certainty. Indeed magic thrives in situations of uncertainty.

Perhaps there are no million dollar models in our corners of the consulting world but whatever their monetary value, our models have a power that is akin to that of magic. These models have power because, like magic, they are technologies of enchantment:

Here’s Gell again:

The technology of enchantment is the most sophisticated we possess. Under this heading I place all those technical strategies, especially art, music, dances, rhetoric, gifts etc., which human beings employ in order to secure the acquiescence of other people in their intentions or project…to enchant the other person and cause him/her to perceive social reality in a way favourable to the social interests of the enchanter.

Models, like magic, are indeed sophisticated weapons:

- Our models communicate a sense of mastery over our material.

- They ‘herd’ their audiences in cognitive spaces that we’ve described and defined

- They then act as intellectual shortcuts – tools to think with – that are defined in terms of our choosing.

Models cause people to “perceive social reality in a way favourable to the social interests of the enchanter” (Gell 1988: 7). I’m sure we’d like to think that our interests are coterminous with those of the people we advise. More often than not I suspect they are. But isn’t it worth remembering the power our models have over those we provide them to and how they exert that power?

Perhaps more importantly it’s worth reflecting on the sometimes restrictive and constraining power that our models might exert over their creators. In pursuit of certainty in the face of uncertainty, is it not sometimes the case that the enchanter becomes the enchanted?

References

Gell, Alfred. 1988. Technology and Magic, in Anthropology Today 4, no. 2: 6-9.

Kiechel. Walter. 2010: The Lords of Strategy: The Secret Intellectual History of the New Corporate World. Harvard Business School Press: Harvard.

Molotch, Harvey. 2003. Where Stuff Comes From: How Toasters, Toilets, Cars, Computers, and Many Other Things Come to Be As They Are, Routledge: New York

0 Comments