This case study examines the use of iterative prototyping to raise concerns important to adolescents and healthcare providers in the participatory design of an intervention to spark open and nonjudgmental sexual and reproductive health discussions. It describes how designers in an interdisciplinary, academic research center used prototyping to engage adolescents and clinicians as co-designers in formative research. Prototypes were created, tested, and refined in focus groups, intercept interviews, semi-structured interviews, and workshops. Varied in content and form, prototypes caused friction—generating key questions, revealing conflicting perspectives and power dynamics, driving exploration, and design. These frictions radiated from a primary tension—the difference between how sexual and reproductive health care is currently delivered and the kinds of care young people desire and need. The resultant intervention radically restructured the adolescent sexual health counseling interaction, empowering adolescents to set the agenda, overcome issues of hierarchy and mistrust, and enhance engagement in their own healthcare.

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020) recommend that healthcare providers regularly spend one-on-one time with adolescents, as early as age 11, as a routine part of care. Early adolescence is a critical developmental stage that requires support in fostering autonomy and decision-making skills, especially relative to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) concerns (Blum et al. 2014; Igras et al. 2014). Regular opportunities to confidentially raise matters of concern and ask questions about sensitive topics to a provider encourages access to care for adolescents and may considerably affect their health and well-being. However, many barriers exist to the access of SRH care by adolescents. In addition to fear, embarrassment, stigma and confidentiality (Miller et al. 2014; Coker et al. 2010), adolescents cite judgmental or unfriendly interactions or distrust of providers as reasons for not seeking care (Johnson et al. 2015; Fox et al. 2010).

This case study describes how a design team in an academic research center created an intervention to spark open and nonjudgmental SRH conversations between adolescents and the providers who care for them. Originally known by its working name, Cards on the Table, the intervention was formally named and branded Let’s Chat by adolescents participating in the last phase of design research; we decided to use the latter in our title to connect it to the finished product and communicate its tone and voice.

Research and design in healthcare rely heavily on qualitative interviewing and often focus on individual behavior. In contrast, this case describes how the use of participatory design with an emphasis on prototyping created a lower-risk approach for less powerful actors—adolescents of color aged 14 to 19—to explore and engage with topics they might otherwise be uncomfortable discussing. As such, it makes an important contribution to ethnographic practice in healthcare by illustrating the ethnomethodological use of prototyping to uncover the norms, understandings, and assumptions around a controversial subject. Prototypes presented topics not historically considered central to SRH care and, as such, brought to light conflicting mental models and existing power differentials. Making frictions explicit was essential to the design of an intervention that sought: (1) to empower adolescents to set their own SRH care agendas and enhance engagement in their own healthcare; and (2) to be acceptable and feasible for healthcare providers to implement.

The case is organized in four main sections. First, as background, we briefly describe the current context of American adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care and the academic research center where formative research for the case was conducted. In the next section, we describe the relevance of participatory design as a methodological approach to balancing power relations and the use of iterative prototyping to define and develop the intervention. Next, in the findings section, we describe five significant frictions that emerged through iterative prototyping, these include:

- Who is sexual and reproductive healthcare for?

- Who defines the parameters of adolescent sexual and reproductive health?

- Bridging the gap between medically-accurate and adolescent-friendly language

- Normalizing or stigmatizing—form factor, color coding, and privacy considerations during topic exploration

- Considering power and privacy during implementation

Finally, we discuss the implications of the frictions to the development of the final instantiation of the intervention now known as Let’s Chat.

BACKGROUND

This section provides the context needed to position the case more broadly. First, we describe limitations in the delivery of SRH care to adolescents in the United States. Then we situate the case in the innovation practice of an interdisciplinary academic research center on Chicago’s south side

Adolescent SRH Care in the United States

The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests routine preventative medical care should include SRH care (Hagan, Shaw, and Duncan 2017). However, most adolescents and young adults do not receive preventative medical care, with even fewer receiving SRH care (Horwitz, Pace, and Ross-Degnan 2018). Structural factors affect adolescent access to care including: inadequate or incorrect information about the location of SRH services or eligibility for care, limited scheduling, cost, the lack of youth-friendly environments, and fears that provider or insurance-related communications will compromise confidential care (Carroll et al. 2012; Hock-Long et al. 2003).

The National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) defines patient-centered care as, “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” (2001, 6). There is strong evidence that when adolescents experience patient-centered care they are more likely to share SRH concerns with their clinician (Nathanson and Becker 1985; Toomey et al. 2016). Yet, most adolescents, especially minority and low-income adolescents, are still not receiving patient-centered SRH care (Fuentes et al. 2018; Toomey et al. 2016). Moreover, studies indicate Black, Latinx, and low-income adolescents and young adults continue to experience medical mistrust, biases, and coercion that affect the access, provision, and uptake of contraceptive care (Gomez and Wapman 2017; Shapiro, Fisher and Diana 1983; Stern 2005). Another study reported transgender youth were more likely to delay care due to LGBTQ-based discrimination than their cisgender peers (Macapagal, Bhatia, and Greene 2016). Persistent disparities reinforce a need to dramatically redesign care delivery to these populations (Fuentes et al. 2018; Martin, Hamilton, and Osterman 2013; Shannon and Klausner 2018).

An Adolescent-Centered Interdisciplinary Academic Research Center

The Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry and Innovation in Sexual and Reproductive Health (Ci3) is a research center at the University of Chicago that addresses the social and structural determinants of adolescent and young adult sexual health. Ci3 envisions a world in which all youth emerge into adulthood with agency over their bodies and futures. It is committed to empowering young people, conducting innovative research, and uncovering opportunities for policy and systemic change.

Founded in 2016, the Ci3 Design Lab invited 31 adolescents of color, aged 14 to 20, to engage as experts of their lived experience in a workshop to explore how SRH care might be improved. The lab’s first workshop series initiated a longer-term effort to design with and for adolescents in processes that supported mutual learning, the authority of adolescents to have a say (not just a voice), and co-realization—core principles associated with the Scandinavian PD tradition (Geppert 2023; Simonsen and Robertson 2013). Workshop participants created low-fidelity prototypes that were later triangulated with other workshop data during analysis by the Ci3 design team. Analysis resulted in seven design principles that became the foundation for an emergent adolescent SRH platform and brand, now known as Hello Greenlight. Because the principles would focus the team on how SRH needed to change from the perspectives of adolescents and drive idea generation for the emergent platform, they were deemed “meta-design principles” as “meta” can refer to both transformation and the need to critically address the current state of a discipline (Merriam-Webster 2023).

The Hello Greenlight meta-design principles were used to develop “How might we…?” prompts for a series of ideation sessions. Stakeholders—adolescents, healthcare providers, subject-matter experts, and institutional leaders—were then recruited to small groups matched to a relevant subset of prompts that were explored in a single ideation session. Ideas generated across all sessions were aggregated, analyzed, and consolidated by the Ci3 design team resulting in 61 distinct concepts. Each concept was then reviewed, marked-up with feedback, and ranked during separate meetings of the Ci3 adolescent and provider advisory councils. Conceived in an ideation session focused on building trusting relationships between providers and patients, the concept “Put your cards on the table” was ranked highest by both advisory councils. It was subsequently prioritized for further exploration by the Ci3 design team, who had already created and tested an initial prototype. Immediately shortened to “Cards on the Table (CoT),” the concept presupposed that an adolescent may not feel confident raising SRH topics or specific questions with their healthcare provider and aimed to build adolescent confidence, agency, and SRH knowledge. The concept was described as follows:

An adolescent is given a deck of cards upon registration that describe questions, concerns, or “hot topics,” and asked to select those of interest to them. The adolescent hands the selected cards to the healthcare provider during their patient visit to help steer the conversation for the visit (example topics: my anatomy, sexual orientation, contraception, anal sex, dental dams, orgasm, et cetera).

Despite the positive evaluation of the concept by the adolescents and provider advisory councils, more research was required. For instance, we did not know the full scope of SRH information desired by adolescents including the kinds of care (i.e., categories in the deck) they felt must be represented to constitute comprehensive SRH; or, the range and number of questions within any given category and their level of specificity. And, once adolescents determined criteria for the latter, we needed to explore and understand how this information may or may not be acceptable to healthcare providers. Additionally, we needed to understand with greater nuance how the intervention should be structured to be feasible for implementation in clinical settings which meant exploring a variety of potential form factors, how they affected adolescent counseling experiences, and the ways they may or may not fit into different clinic workflows. The next section will describe how iterative prototyping and prototypes were employed to define and develop Cards on the Table.

METHODOLOGY

The above limitations of SRH care underscore the need to create equitable, accessible, and acceptable patient-centered adolescent SRH care. To address the significant power differential between adolescents and providers, intervention development was informed by the principles and ethics of Scandinavian participatory design (PD). PD is a political tradition concerned with equalizing power relations through the “genuine participation” of less powerful actors in the design process (Robertson and Simonsen 2013). Unlike one-way data collection techniques, such as observation or key informant interviews, participation is genuine when there is opportunity for mutual learning—that is, opportunity for participants and designers to learn enough about each other’s worlds relative to a specific matter of concern. In PD, this kind of two-way learning is often facilitated through prototyping—the use of tangible artifacts—to co-construct and debate potential affordances and/or consequences of an idea, otherwise known as “co-realization” (Blomberg and Karasti 2013; Bratteteig et al. 2013). Blomberg and Karasti (2013:99) suggest that co-realization “integrates ethnomethodology’s analytic mentality” with PD’s practical orientation “to achieve ‘design-in-use.’” Kensing (1983) argues that in order for participation to be genuine, less powerful actors must have access to: (1) information, (2) resources—including, for instance, time, money, and expert assistance—and (3) decision-making power (i.e., having a say, not just a voice). The quality of the latter affects not only the procedures of participation, but also the experience of participation by less powerful actors (Geppert 2023).

In the case of Let’s Chat, formative research was conducted with adolescents ages 14 to 19 (n=82) and healthcare providers (n=31) who were engaged as co-designers in a PD process that relied heavily on prototyping as an activity (Hillgren, Seravalli, and Emilson 2011) to iteratively explore research questions and/or specific issues through concrete manifestations (Bødker and Grønbaek 1991). Formative research was conducted in four phases. This case study is bound to the first three phases as these research activities revealed frictions that were central to the ongoing development of Cards on the Table (now known as Let’s Chat). The methods used in the first three phases and their sub-phases are described below.

Phase 0: Determining merit within Ci3

In short, the phrase “put your cards on the table” encapsulated the ethos of the proposed intervention such that a cardholder should have: (1) access a range of relevant SRH topics, associated vocabulary, and questions; (2) the power to decide which topics and questions are relevant to them; and (3) the opportunity to hand their questions to another person who can answer with medically accurate information (e.g., healthcare provider, sex educator, parent, trusted adult, etc.). Organized in this way, the proposed intervention shifts the power hierarchy and makes space for adolescent confidence, agency, and sexual health-related knowledge. Directly following the ideation session where Cards on the Table originated, which did not include adolescents, the Ci3 design team decided it was an easy concept to prototype and test with adolescents to determine if it had merit.

Here, it is important to note that despite the strong imagery, the phrase “put your cards on the table” evoked, it was only meant to keep the ethos of the intervention in focus, it was not a design dictate for the final instantiation. That said, the phrase made obvious how an initial prototype could be organized to communicate units of SRH information. The first prototype was designed as a card sorting activity (Martin and Hanington 2012; Spencer 2009); each card presented a SRH question, with the goal for the deck of cards to span relevant topics and information, generate curiosity, and prompt question asking. Because the Ci3 design team was solution agnostic, the first prototype served as a boundary object. Susan Leigh Star states:

Boundary objects are those scientific objects which both inhabit several communities of practice and satisfy the informational requirements of each of them. Boundary objects are thus objects which are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. They are weakly structured in common use, and become strongly structured in individual-site use. These objects may be abstract or concrete.

(Star 2015, 157)

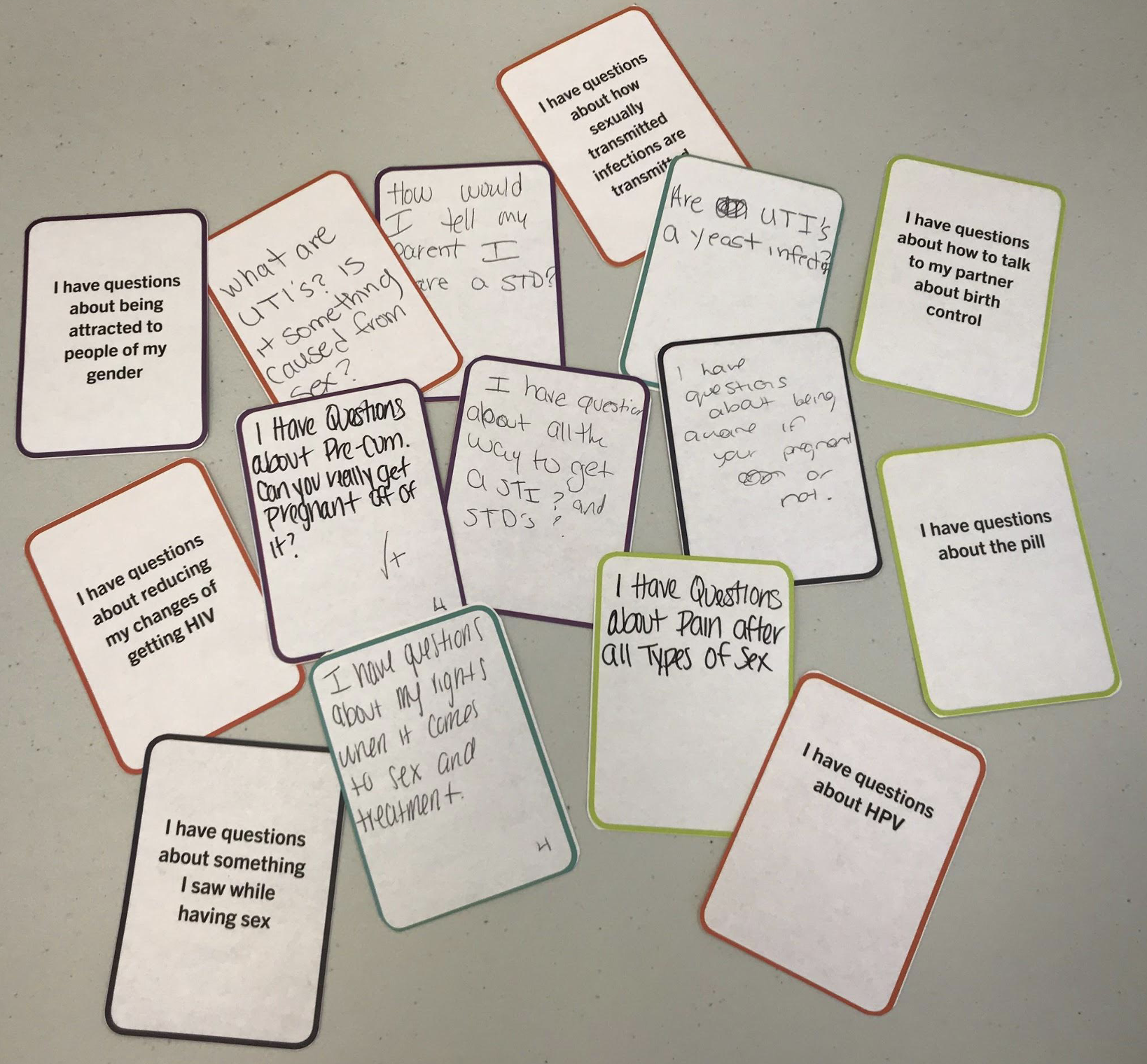

The initial prototype was tested with three small focus groups comprised of Ci3 youth advisory council members (n=11), who were introduced to the concept goals, context of use, and then invited to explore 23 SRH questions printed on separate cards. After becoming familiar with the questions, each group was asked to sort each card into one of three categories—“like”, “dislike”, or “don’t understand or confusing”—and write down any questions they would like to add using blank cards, if desired. Afterwards, each group discussed their choices with the facilitator, a Ci3 design team member.

The final card sorts from each focus group were photographed after the discussion was completed and the facilitators met to debrief and further document discussion themes; documentation was later triangulated and used to inform the design research brief for phase 2.

Phase 1: Determining Merit External to Ci3

The Ci3 design team was invited to participate in two adolescent-led, health-related, community pop-up events organized through a community-based organization with a longstanding history of developing youth to be empowered, informed, and active citizens who will promote a just and equitable society. Focused on holistic self-care, the events sought to provide access to a range of resources relevant to adolescents and their families including, for instance, cooking and fitness classes, introductions to local healthcare institutions and family planning services, and the opportunity to sign up for Medicaid. The pop-ups that Ci3 attended were held in neighborhoods located on Chicago’s west side, the population of one community was majority Black (non-Hispanic) and the other predominantly Hispanic/Latino (any race).

Ci3 welcomed the high school-aged participants to learn about Ci3 and how we used PD to improve SRH with and for adolescents using Cards on the Table as an example. We encouraged pop-up participants to pick up the deck as we explained the goals and context of use of the concept and how their feedback could help our team decide if the concept was worthwhile and merited full development. If a participant was interested in helping (n=50), using the same deck as in phase 0, they were asked to sort the cards, into one of three categories,—“like”, “dislike”, or “don’t understand or confusing”—and offered blank cards to write down any questions they would like to add, if desired. After the cards were sorted, given time constraints, participants were only asked to discuss the questions they placed in the “dislike”, or “don’t understand or confusing” categories. The final card sorts were photographed, facilitators wrote down headlines following the event, and the team met to debrief and discuss themes, with additional observations and insights documented in meeting notes; documentation was later triangulated and used to inform the design research brief for phase 2.

Phase 2: Co-Designing with Stakeholders

Both phases above provided evidence indicating the potential acceptability of Cards on the Table to initiate SRH conversations and with this Ci3 leadership approved the formal development of the intervention. The second phase of prototyping began with five research questions, these included:

- What content speaks to the most common SRH concerns, while embracing a wide range of topics?

- How might we balance using language that resonates with adolescents and medically accurate terminology?

- What are the different ways that adolescents might use the intervention? For instance, will questions in the deck spark new questions because the former provides young people new vocabulary to draw on?

- For what age groups and contexts of use is the intervention appropriate?

- What advantages does the intervention offer healthcare providers? How is it beneficial rather than a burden?

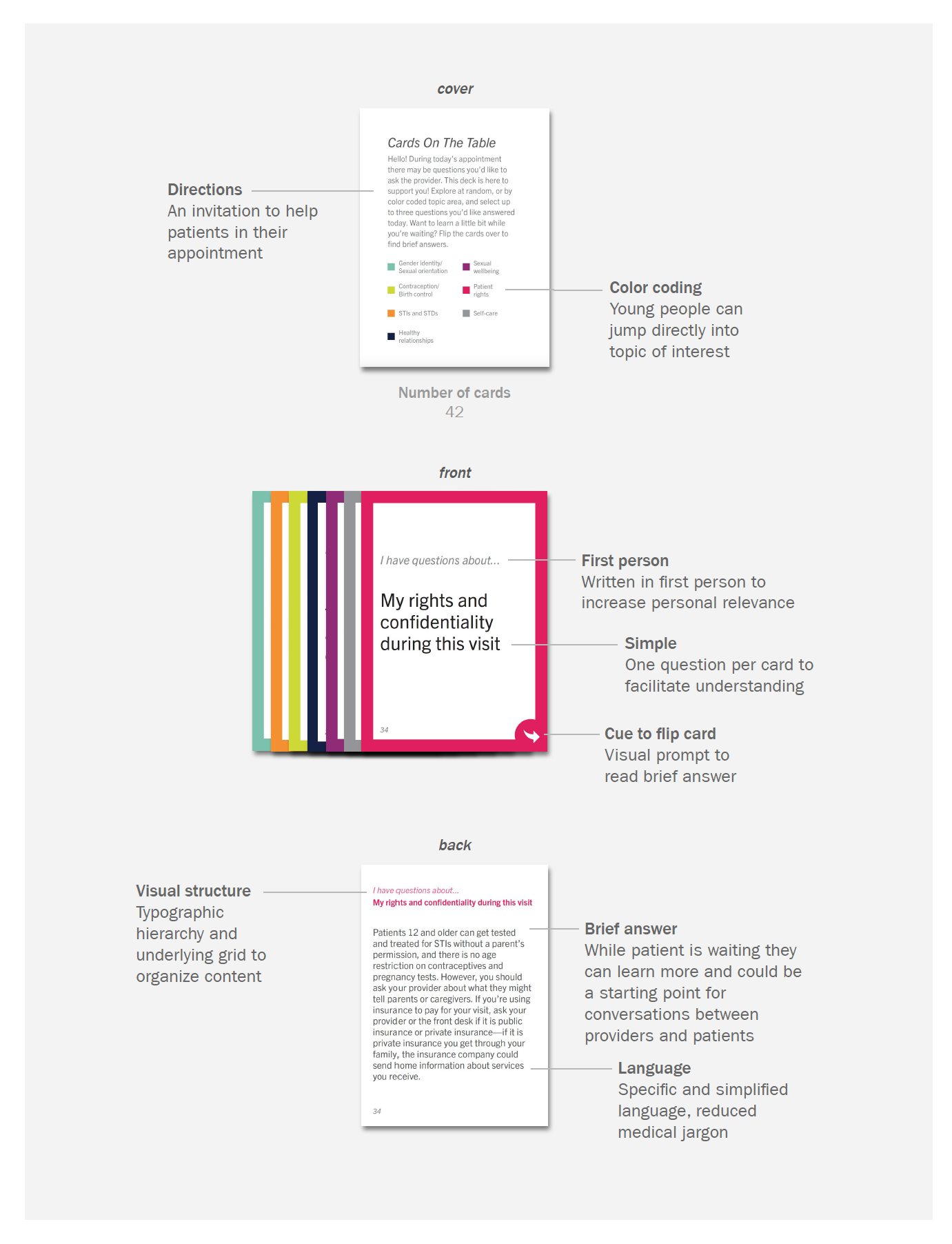

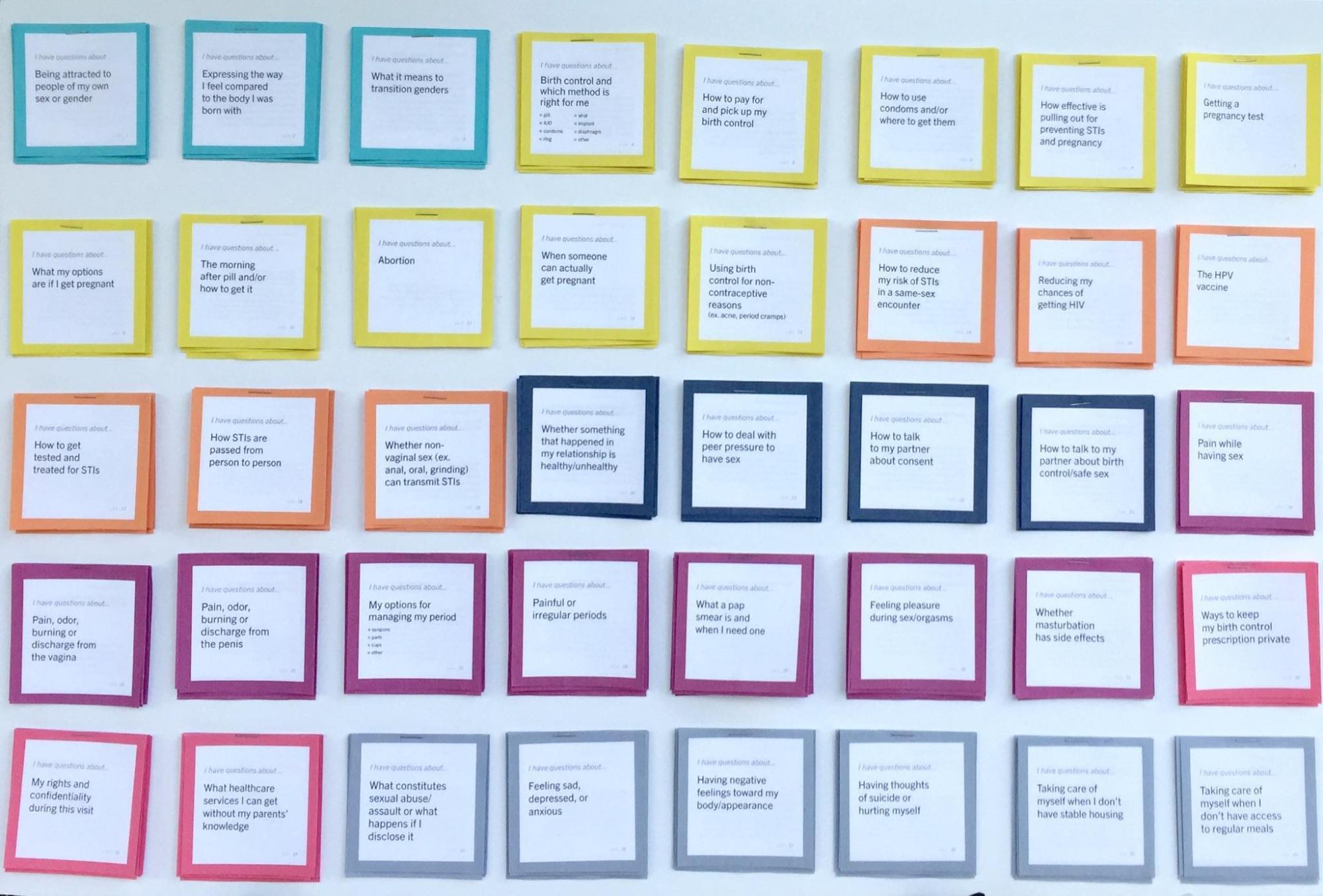

In phase 2, questions and categories were further refined, and back-of-card content was drafted to provide cursory information, not a comprehensive answer, about a question (see Figure 2). The rationale for this approach was to give just enough information for an adolescent to determine if it was a question they would like to ask since they may not yet have the vocabulary to describe their SRH concern. There were six different content prototypes in this phase, with the number of cards in each deck ranging from 40 to 56. In addition to the deck of cards, the Ci3 design team created 11 physical prototypes to explore different ways the form factor might support content filtering and privacy.

Phase 2 design research was conducted in three sub-phases. In sub-phase A, healthcare providers who cared for adolescents (n=20) were recruited for semi-structured interviews and a card sorting activity. Participating providers included: obstetricians/gynecologists (n=2), nurse midwives (n=2), pediatricians (n=3), residents (n=5), advanced practice nurses (n=3), medical assistants (n=3), a psychologist, and a social worker.

In sub-phase B, adolescent patients (n=9) in an obstetrics and gynecology clinic browsed the card deck, selected questions, and discussed them with a provider, then gave feedback on the content and structure of the interaction. Lastly, in sub-phase C, adolescents were recruited (n=12) from the Chicagoland area to a workshop that included mock consultations with healthcare providers. Data collection from each sub-phase was analyzed in an ongoing manner to inform iterations of content and culminated in a Ci3 design team synthesis session to consolidate learnings toward finalizing the intervention design in phase 3. Findings from phases 0, 1, and 2 are described next.

FINDINGS

A primary tension defined intervention development: the difference between how adolescent SRH care is currently provided and the kinds of care adolescents desire and need. From here, frictions radiated and caused debate as prototypes were tested with a variety of stakeholders. Frictions intersect across a variety of mental models connected to intervention framing, communication strategy, and delivery, and as a result they are not mutually exclusive to one dimension or another. The next section describes five frictions foregrounded as stakeholders tested prototypes based on an analysis of the data collected during the formative research phases described above. The frictions include:

- Who is sexual and reproductive healthcare for?

- Who defines the parameters of adolescent sexual and reproductive health?

- Bridging the gap between medically-accurate and adolescent-friendly language

- Normalizing or stigmatizing—form factor, color coding, and privacy considerations during topic exploration

- Considering power and privacy during implementation

Friction 1: Who is Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare For?

Historically, health care has emphasized the biological aspects of SRH, from menstruation, contraception, and pregnancy to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and diseases (STDs), with SRH care prioritizing cisgender, heterosexual, female bodies. This framing places an undue responsibility for the emotional, intellectual, and physical labor involved in making SRH decisions on cisgender, heterosexual girls and women. In doing so, it excludes a significant proportion of the population who may desire and benefit from more robust engagement with SRH information and care including cisgender boys and men as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, transgender, queer, and nonbinary individuals.

In contrast to the historical framing of SRH, an expansive view of SRH informed prototype content in all phases of design research. While giving feedback on a Cards on the Table prototype, a pediatric resident noted, “I think providers don’t ask males about sexual and reproductive health as much because medicine and society is so focused on contraception.” Young men who participated in prototyping were well aware of this dynamic and how it left them in the dark despite their curiosity. One male participant noted, “When I ask my doctor about things like [the difference between HPV and HIV], there are limitations to his answer because he knows cervical cancer and things like that don’t relate to me.”

Cards about gender identity and sexual orientation included questions about being attracted to people of one’s own sex or gender, gender dysphoria, and gender transition. Some adolescents who participated in prototype testing were ambivalent about the inclusion of these topics because they were not personally relevant, felt it was deeply personal information, or felt the topics belonged to discussions with a psychologist or social worker. On the other hand, some adolescents recognized these topics could be a matter of life or death for their peers. For some, the topics were right on time. For instance, one adolescent exclaimed, “Girl condoms, is this a thing?!” She noted she had a first girlfriend who, like her, had only also dated guys and felt that she did not know what she needed to know so Cards on the Table facilitated her thinking. One medical assistant was uncertain about the inclusion of the gender identity and sexual orientation topics because they did not think adolescents could decide on this until they were older. Yet, a different medical assistant in the same practice shared that he “always tries to make trans patients feel welcome and respects pronouns.” In summary, healthcare providers who tested a prototype of Cards on the Table displayed a variety of reactions to the inclusion of these topics, revealing frictions within the medical community. The majority of providers were open, if hesitant, to the inclusion of these topics, but indicated they might not be prepared to answer them due to personal discomfort and/or a lack of training—nor would their peers.

Friction 2: Who Defines the Parameters of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health?

SRH often intersects with broader concepts of identity, social-emotional well-being and social determinants of health, which often go unaddressed in traditional SRH education and counseling. In several instances, content that addressed these concepts challenged healthcare providers accustomed to a biomedical model of healthcare that offers “just enough” information to adolescents.

For example, the intervention included the topic of feeling pleasure during sex and orgasms in the sexual well-being category. One medical assistant responded, “I don’t think asking about feeling pleasure is an appropriate question. Young people don’t know what they’re doing.” Another medical assistant agreed that the question was not appropriate with the rationale that talking about pleasure during sex would make adolescents want to have sex. On the other hand, a provider specializing in pediatric and adolescent gynecology adamantly argued that there is reliable data to support:

…providing condoms doesn’t increase sexual activity and providing emergency contraception in advance does not lead to more sexual behaviors. Exposure to knowledge is the best way to get more comfortable with these issues. Providers need to broaden their horizons.

The intervention also addressed social determinants of health in the self-care category, which included content regarding sexual abuse or assault, mental health, body image, self-harm and suicide, to food and housing insecurity. An advanced practice nurse noted that questions in this category “are valuable because though they’re not about SRH, they could bring up things related to SRH or increased risk.” Providers responded more favorably to the inclusion of these topics because current screening tools may not capture sufficient nuance. However, providers also noted they weren’t necessarily prepared with resources to answer questions about them. A provider who specializes in pediatric and adolescent medicine pointed out that Cards on the Table “covers a lot of the things that aren’t necessarily directly addressed on the Bright Futures form,” an assessment tool universally recommended for adolescents 12 and older to screen for developmental concerns; behavioral, social, or emotional concerns; maternal depression; adolescent depression and suicide risk; substance use; and oral health concerns. The same provider continued, Bright Futures is:

…a little bit broad-based. As a clinician, it’s a little bit cumbersome to get through… in a perfect world. You have a kid, they check in, they’re flipping through this [Cards on the Table]. They pick their three cards. They hand them to the MA [medical assistant] or the nurse who is trained to answer these questions… [For instance, the] question on “Where can I get free contraception?” Well, since a lot of Title X funding is going away, I don’t know the answer to that anymore, but those are things where resources can be provided. “Where can I get condoms?” Great! The nurse goes and grabs a bag full of condoms in a discreet bag and says, “Here, put this in your backpack.” … So, it helps to do some targeted anticipatory guidance, rather than just vomit anticipatory guidance about [for instance,] no more than two hours of screen time and to make sure that you’re eating five servings of fruits and vegetables and that you’re getting 10 hours of sleep…

A third provider noted the topics were good and suggested adding content about parents, dealing with cyber/online/social media issues, such as sharing explicit photos on Snapchat.

Friction 3: Bridging the Gap Between Medically-Accurate and Adolescent Friendly Language

Adolescents can find it difficult to access quality, medically accurate, and adolescent-friendly SRH information on their own. Cards on the Table sought to put relevant SRH topics and terms in the hands of adolescents at an opportune moment when their questions could be answered by a qualified professional. At the same time, adolescents have shared that medically accurate information can be overwhelming or boring, and though it is specific and helpful to healthcare providers, it can represent a barrier to understanding and cultivating rapport with adolescents. Cards on the Table sought to bridge this communication gap by creating questions and introductory content accessible enough to an adolescent population that they could signal the topics they want more information about and start conversations with their provider.

In particular, word choice arose as a tension. In phase 2, a medical assistant suggested “that patients might feel creepy” about the word masturbation. A general pediatrician shared:

At least a couple of times, I’ve asked kids before the [physical] exam, “Are you having a discharge?” And, they’ll say, “No.” And I examine, and they’re having florid discharge. You’re like [to yourself], “How did they not know that?” So, kids don’t always know. I mean they may not pick this card because they just don’t know… Could it be the word “discharge”? I say, “Is something coming out of your penis that’s not urine?” I actually put it that way. So that should be pretty obvious… Words are important.

During phase 0 and 1 prototype testing, adolescents indicated that they use different words for anatomy, and many, especially males, did not know what acronyms like IUD and HPV meant. In phase 2, during an activity completed by adolescents during the mock consultation workshop, they called out words or phrases they did not know and suggested less technical terms or wording they thought would be better. Instead of “masturbation,” they suggested, for instance, “playing with yourself,” “pleasing yourself,” and “jerking off.” Instead of the “morning after pill,” participants were more familiar with “Plan B.” Many participants recommended other options for “disease transmission,” including “spread,” “passed along,” or “passed on.” For the word “disclose,” participants shared that either “talk about,” or “reveal,” would be more easily understood.

Friction 4: Normalizing or Stigmatizing—Form Factor, Color Coding, and Privacy Considerations During Topic Exploration

Cards on the Table wanted to promote curiosity and exploration of SRH topics in a manner that did not cause fear or shame, ideally normalizing sexual health terms, information, and questions. To that end, the seven categories of care presented in the intervention were color-coded to improve browsing. During phase 2, the Ci3 design team tested two form factors with adolescents and providers—the deck of cards, and another form called “Cards on the Wall” (pictured below), which presented each of the questions as individual tear sheets, analogous to a prescription pad used by healthcare providers. Both form factors had different affordances for scanning categories and questions which surfaced new tensions across stakeholders.

Universally, healthcare providers agreed that Cards on the Wall took up too much space in an outpatient setting where exam rooms are shared by different specialties. For the intervention to work, providers said it must be portable and easily shared with and collected from patients, or use a technology common to both stakeholders. In contrast, adolescents preferred a wall installation over a card deck because the content was easier to scan and they could easily manage the questions they tore off and take them home. In general, adolescents thought it was awkward to sort through the card deck because the exam room lacked a surface to support the activity. Regardless of form factor, adolescents stated they would be less comfortable or would not engage with the intervention if a parent was present. A provider specialized in pediatric and adolescent gynecology discussed their conflicting thoughts about the color coding:

…anytime you recognize there are categories, I think it could be distractive. People could feel bad about having a lot of questions about a specific category… from the patient point of view, they could spend time on what those colors have in common and get distracted from the actual purpose.

In contrast, adolescents found color coding helpful in identifying categories that were relevant to them or exploring categories that they did not know anything about.

Friction 5: Considering power and privacy during implementation

For the intervention to be effective, it would need to be both acceptable to adolescents and healthcare providers and feasible to implement in different clinic workflows. Prototype testing revealed that power dynamics differed depending on how the intervention was implemented. If, for instance, the deck of cards was offered to adolescent patients upon check-in, a parent or caregiver might prevent the adolescent from using it. By contrast, if healthcare providers managed the deck and handed it to an adolescent after a parent or caregiver had stepped out for the one-on-one time recommended by ACOG and the CDC, an adolescent could decide to engage with it or not. If providers managed the deck, adolescents feared one or both of two scenarios: (1) cards in the deck might get lost over time (a fear also mirrored by healthcare providers); and (2) a provider might choose to filter out cards they felt were inappropriate. Either way, from the perspective of adolescents, when cards that were intended to be part of the deck were not included, essential SRH information was not readily accessible to their peers. Many adolescents indicated that they preferred to have access to the deck at check-in so they could browse while waiting to be roomed. Some providers noted, however, the best time would be when the patient is being roomed to avoid adding more work by administrative staff at check-in.

After browsing, adolescent patients were invited to select up to three cards for discussion. Some adolescents expressed the importance of handing the cards directly to the provider to initiate the discussion and so the cards could be referenced together. One provider felt that there may be adolescents who might be more comfortable with a passive interaction, like putting the cards in a slot outside of the exam room or completing a checklist instead of directly sharing three specific cards. Additionally, this provider noted:

I would like to have the opportunity to look at the cards before going in, to know what topics were chosen before going in the room. Because if I need to look something up, I can be prepared. No one wants to look like they don’t know what they are talking about.

This reflection echoed the feelings of many other providers. On average, using Cards on the Table added an additional four minutes to a fifteen-minute appointment time when young people selected three cards or less. One adolescent shared that the intervention included “the right amount of cards. It didn’t feel like too much or too little and was easy to use.” Despite noting the relevancy of the categories, some providers expressed concern about the number of questions.

CONCLUSION

Prototype testing uncovered a diversity of perspectives about what constitutes relevant and acceptable SRH topics as well as intervention characteristics that could affect accessibility and feasibility during implementation in healthcare settings. When these perspectives were at odds, the frictions they produced delineated the boundaries of the design space from the viewpoints of both less and more powerful actors, thus democratizing how that space was constructed. As the Ci3 design team moved into the third and final phase of formative research (to be described in a subsequent publication), we did so with intention and recognition that the design of the final intervention would not be able to reconcile or mitigate all of the frictions that emerged in phases 0, 1, and 2.

This case described how the use of participatory design with an emphasis on prototyping expanded the epistemic authority of adolescents in the design of a healthcare intervention. This approach could be extrapolated to other ethnographic studies in other fields when two or more groups of stakeholders have an extreme power differential as a way to surface and lean into frictions and ensure that power dynamics are disrupted. The inclusion of less powerful actors in design research processes can redistribute power and social relations and support mutual learning to ensure design research is strategically useful to challenging social and structural disparities that affect health equity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Melissa L. Gilliam, MD, MPH, the Founder and former Director of Ci3, for her leadership which made the development of Let’s Chat possible and for the expertise she brought to its design. We are grateful to the Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence at the University of Chicago and an anonymous funder for project support. We thank the UChicago Medicine Section of Complex Family Planning and Contraceptive Research, and Comer Children’s Hospital Department of Pediatrics and Mobile Medical Unit; and, the many young people who brought their lived experience and expertise to the design of Let’s Chat.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Amanda A. Geppert (she/they) is the Director of Design at Ci3 at the University of Chicago where she leads the co-design of novel interventions to advance the well-being of adolescents most affected by systemic inequity. She obtained her Ph.D. in Design from the Institute of Design at Illinois Tech and holds an M.P.H. from the University of Illinois Chicago. Email: amandageppert@gmail.com

Julia Rochlin (she/her) was a Ci3 Design Research and Strategy Intern and is currently a Senior Design Researcher at Conifer Research. She specializes in ethnographic methods and design research. Hailing from Rio de Janeiro, she graduated from the Institute of Design (MDes 2020) in Chicago. Julia focuses on enhancing the well-being of people by challenging conventional thinking in organizations through innovative interventions. E-mail: juliarochlin@gmail.com

R. McKinley Sherrod (she/her) was a Ci3 Design Research and Strategy Intern, holding an MDes from the Institute of Design and dual degrees in Sociology and Gender Studies from Kenyon College. Now a Senior Design Strategist at the University of Illinois Chicago, she focuses on designing healthcare and social systems aligned with people’s lived experiences. McKinley is passionate about using design to challenge the status quo and promote equitable futures. Email: mckinleysherrod@gmail.com

Crystal Pirtle Tyler, PhD, MPH (she/her) was formerly Executive Director of Ci3. As the Chief Health Officer at Rhia Ventures, she oversees organizational strategy, programs and translates the needs of the women and birthing people most affected by systemic inequity into programming that fosters equitable reproductive health products and services. She has over 15 years of experience advancing reproductive and maternal health equity.

Laura Paradis (she/her) was formerly a Design Lead at Ci3 and is currently a Senior Service Designer working closely with the Veterans Experience Office. She is a senior human-centered design professional whose work prioritizes public benefit and values design that creates space for inclusion, clarity, and access. E-mail: laurayparadis@gmail.com

Emily Moss (she/her) was formerly a Hybrid Designer at Ci3. At the Lab at OPM, Emily is a civic design researcher and strategist who partners with federal agencies to improve services and programs through human-centered design. Emily’s expertise includes design research, trauma-informed design practices, co-design and prototyping-to-learn. E-mail: emily.moss0024@gmail.com

Sierra Bushe-Ribero DNP, CNM, WHNP-BC (she/her) was formerly a Clinical Lead at Ci3. As the Clinical Director of Women and Newborn Services she oversees maternal clinical care practice at a large tertiary hospital. Sierra’s practice research is focused on closing health disparity gaps in sexual, gender, and ethnic minority communications through the education of healthcare providers, staff, and students.

REFERENCES CITED

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2020. “Confidentiality in Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 803.” Obstet Gynecol: 171–7. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/04/confidentiality-in-adolescent-health-care, accessed September 8, 2023.

Blomberg, Jeanette, and Helena Karasti. 2013. “Ethnography: Positioning Ethnography within Participatory Design.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 86–116. New York: Routledge.

Blum, Robert W., Nan Marie Astone, Michael R. Decker, and Venkatraman Chandra Mouli. 2014. “A Conceptual Framework for Early Adolescence: A Platform for Research.” Int J Adolesc Med Health 26(3): 321–31.

Bødker, Susanne, and Kaj Grønbaek. 1991. “Cooperative Prototyping: Users and Designers in Mutual Activity.” Int. J. Man-Machine Studies 34: 453–478.

Bratteteig, Tone, Susanne Bødker, Yvonne Dittrich, Preben Holst Mogensen, and Jesper Simonsen. 2013. “Methods: Organizing Principles and General Guidelines for Participatory Design Projects.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design., edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 117–144. New York and London: Routledge.

Carroll, Chris, Myfanwy Lloyd-Jones, John Cooke, and Jenny Owen. 2012. “Reasons for the Use and Non-Use of School Sexual Health Services: A Systematic Review of Young People’s Views.” Public Health 34(3): 403–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. “Teen Health Services and One-On-One Time with A Healthcare Provider: An Infobrief for Parents.” https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/healthservices/pdf/oneononetime_factsheet.pdf, accessed September 8, 2023.

Coker, Tumaini R., Havinder G. Sareen, Paul J. Chung, David P. Kennedy, Beverly A. Weidmar, and Mark A. Schuster. 2010. “Improving Access to and Utilization of Adolescent Preventive Health Care: The Perspectives of Adolescents and Parents..” J Adolesc Health 47(2): 133–42.

Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. 2001. “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK222274.pdf, accessed September 8, 2023.

Fox, Harriette B., Margaret A. McManus, and Shara M. Yurkiewicz. 2010. “Adolescents’ Experiences and Views on Health Care. No. 3.” Washington, D.C.: The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health.

Fuentes, Liza, Meghan Ingerick, Rachel Jones, and Laura Lindberg. 2018. “Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Reports of Barriers to Confidential Health Care and Receipt of Contraceptive Services.” Journal of Adolescent Health 62: 36–43.

Geppert, Amanda Anne.“Design for Equivalence: Mutual Learning and Participant Gains in Participatory Design Processes.” PhD diss., Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/design-equivalence-mutual-learning-participant/docview/2858158969/se-2, accessed October 1, 2023.

Gomez, Anu Manchikanti, and Mikaela Wapman. 2017. “Under (Implicit) Pressure: Young Black and Latina Women’s Perceptions of Contraceptive Care..” Contraception 96(4): 221–226.

Hagan, Joseph F., Judith S. Shaw, and Paula M. Duncan, eds. 2017. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Hillgren, Per-Anders, Anna Seravalli, and Anders Emilson. 2011. “Prototyping and Infrastructuring in Design for Social Innovation.” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 7(3–4): 169–183.

Hock-Long, Linda, Roberta Herceg-Baron, Amy M. Cassidy, and Paul G. Whittaker. 2003. “Access to Adolescent Reproductive Health Services: Financial and Structural Barriers to Care.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35(3): 144–147. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3097767.

Horwitz, Mara E. Murray, Lydia E. Pace, and Dennis Ross-Degnan. 2018. “Trends and Disparities in Sexual and Reproductive Health Behaviors and Service Among Young Adult Women (Aged 18-25 Years) in the United States, 2002-2015.” American Journal of Public Health (108): S336–S343.

Igras, Susan M., Marjorie Macieira, Elaine Murphy, and Rebecka Lundgren. 2014. Investing in Very Young Adolescents’ Sexual and Reproductive Health. Glob Public Health 9(5): 555–69.

Johnson, Katherine M., Laura E. Dodge, Michele R. Hacker, and Hope A. Ricciotto. 2015. “Perspectives on Family Planning Services among Adolescents at a Boston Community Health Center.” Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 28(2): 84–90.

Kensing, Finn. 1983 “The Trade Unions Influence on Technological Change.” Proceedings of the IFIP WG 9.1 Working Conference on Systems Design For, With, and by the Users, September 1982. Riva Del Sole, Italy: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Macapagal, Kathryn, Ramona Bhatia, and George J. Greene. 2016. “Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults.” LGBT Health 3(6): 434–42.

Martin, Bella, and Bruce Hanington. 2012. Universal Methods of Design. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Martin, Joyce A., Brady E. Hamilton, and Michelle JK Osterman. 2014. “Births in the United States, 2013. NCHS data brief, 175.” Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Meta. 2023. Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary. Merriam Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meta, accessed September 8, 2023.

Miller, Melissa K., Joi Wickliffe, Sara Jahnke, Jennifer S. Linebarger, and Denise Dowd. 2014. “Accessing General and Sexual Healthcare: Experiences of Urban Youth.” Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 9(3): 279–90.

Nathanson, Constance A., and Marshall H. Becker. 1985. “The Influence of Client-Provider Relationships on Teenage Women’s Subsequent Use of Contraception.” American Journal of Public Health 75(1): 33–38.

Robertson, Toni, and Jesper Simonsen. 2013. “Participatory Design: An Introduction.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design., edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 1–17. New York and London: Routledge.

Shannon, Chelsea L., and Jeffrey D. Klausner. 2018. “The Growing Epidemic of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescents: A Neglected Population.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics 30(1): 36–43.

Shapiro, Thomas, William Fisher, and Augusto Diana. 1983. “Family Planning and Female Sterilization in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 17(1): 1847–1855.

Simonsen, Jesper, and Toni Robertson, eds.. 2013. Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. New York and London: Routledge.

Spencer, Donna. 2009. Card Sorting: Designing Usable Categories. Brooklyn, New York: Rosenfeld Media.

Star, Susan Leigh. 2015. “Misplaced Concretism and Concrete Situations: Feminism, Method, and Information Technology.” In Boundary Objects and Beyond: Working with Leigh Star, edited by Geoffrey C. Bowker, Stefan Timmermans, Adele E. Clarke, and Ellen Balka, 142–167. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press.

Stern, Elizabeth Minna. 2005. “Sterilized in the Name of Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 95(7): 1128–1138.

Toomey, Sara L., Marc N. Elliott, David C. Schwebel, Susan R. Tortolero, Paula M. Cuccaro, Susan L. Davies, Vinay Kampalath, and Mark A. Schuster. 2016. “Relationship between Adolescent Report of Patient-Centered Care and of Quality of Primary Care.” American Pediatric Association 8(16): 770–776.