Thomas Wendt is one of many eloquent voices urging designers and ethnographers to take responsibility for the social roots and implications of our work. This might mean using participatory approaches, or expanding the scope of our research to understand the larger social implications of a project more fully. It might even mean refusing to work on certain projects all together.

Any choice we make about how we work and what we work on will depend on our own beliefs and political commitments, as well as the constraints or freedoms of our workplaces. Those of us working within corporations may have fewer liberties when it comes to choosing and directing the work that we do day-to-day. These are struggles I have had in trying to make a meaningful difference as an ethnographic researcher from within the confines of the various large technology companies in which I have worked for more than 25 years. I’ve witnessed and contributed to many transformative technological and sociocultural changes, and in the thick of it I was not always cognizant of the inherently political nature of my work or the role that ethnographic research can have in creating social change beyond the companies I have worked in.

In recent years, however, my thinking has evolved. This is an abbreviated story of that evolution. I now realize that research and design are inherently political activities, and that I, as a researcher, have a personal imperative to work toward “the greater good” even when I am “working for the man.”

Working on the Innovation Side

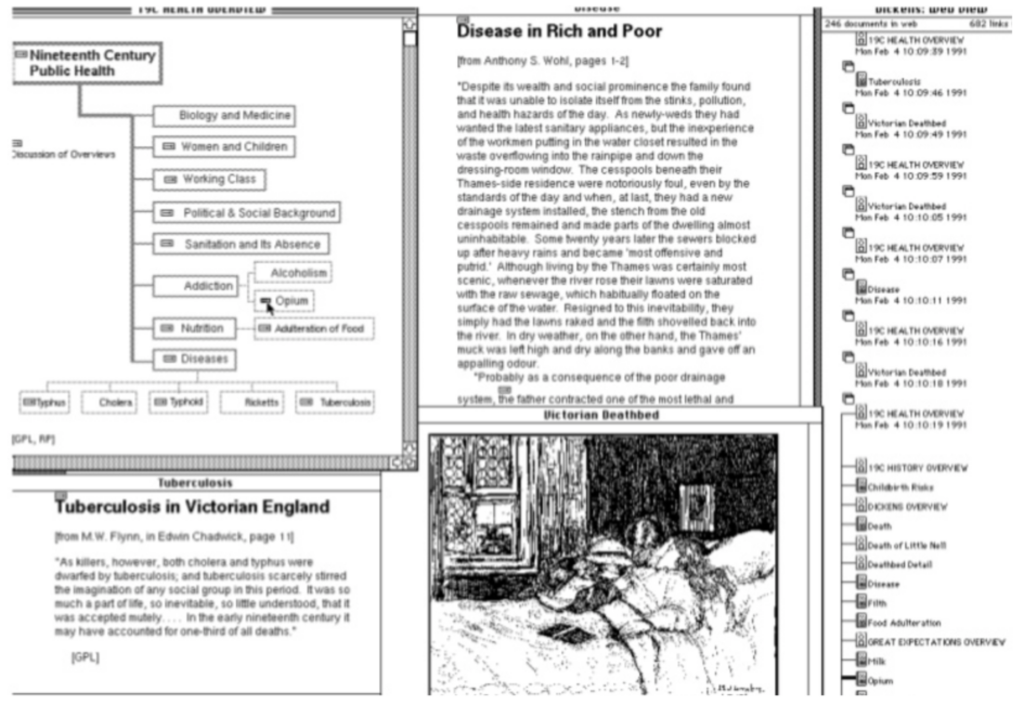

I started out as an ethnographer in the mid-1980s studying academia’s first flirtations with network computing and its applications in educational settings.1, 2 With the advent of personal computing, and the possibility of an interconnected multi-media world, we imagined a future where non-linear thinking would become the norm.3 That lofty idea has not been realized, but network computing, and the World Wide Web have indisputably changed our personal, social, and political lives.

Screenshot from Intermedia, a hypertext precursor to the web that was developed at Brown University (1985 to 1990). I worked on a team of social scientists who were evaluating the software in an educational setting.

Some of the changes have been improvements, and there has never been a time in my career that I haven’t felt that we were on the edge of great technological discoveries that would lead to positive changes in how we live and think. Ostensibly, and idealistically, today’s tech industry is poised to solve many of earth’s problems—from providing clean water and energy to making work easier and safer. And yet each of these advances will undoubtedly come at an unknown price.

Newton’s third law of physics, “every action causes an equal and opposite reaction,” provides an apt metaphor for understanding the negative consequences of technological advancement: for every technological advancement, we see a proportional negative consequence, or what Ed Tenner calls “The Revenge Effect”. 4 For example, the Internet and its subsequent explosion into the public web facilitated information communications and maintenance of social relationships, enabled e-commerce, and countless other advantages, but at the expense of personal privacy and the added risk of being hacked, stalked, or plagued with unwanted advertising. Personal computing in all of its forms has reproduced or created social inequities related to access and opportunity, contributed to numerous public health issues (e.g., overuse injuries, postural problems, sedentary behaviors), and added to the world’s environmental problems (e.g., increased carbon footprint in production and use, problems around appropriate disposal and recycling, etc.).

For most of my career I have sat uncomfortably on the side of technological innovation, inventing methods for tracking people’s behavior, creating integrated computing environments, helping to develop personal assistants, all in the name of doing research to improve people’s everyday lives—while knowing with certainty that the very things I was helping to create would one day “bite back.” My discomfort has urged me down a path of trying to better understand some of the consequences of invention, and to approach every research topic from the broadest perspective possible.

From Tactical to Politically Situated

Ethnographers in industry are often tasked with providing tactical insights; for example, providing analysis that will inform the design of a particular product or product category. We are often asked to investigate micro-design-related problems. Timelines for our research can be tight, and budgets may be small. Stakeholders may not readily understand the value of taking an ethnographic approach to uncovering opportunities beyond the margins of their immediate questions, and they frequently do not consider the broader social implications of their innovation paths. For most of my early career, I believed that my job was to deliver value to the company, given those constraints.

In recent years, I have come to the conclusion that it is possible to deliver broader value—to be true to stakeholders in the company, addressing their micro-questions, while at the same time being true to myself, framing narrowly framed work objectives within broader global and social narratives of political importance. Two recent projects are examples. Each began as a tactical project related to specific products Intel was developing, then developed into projects situated firmly in the global and socio-political narratives around gender and how our specific products could interact with those narratives.

MakeHers

Several years ago, as the Internet of Things hype began to crescendo and the “Maker Movement” began to gain steam, I started an exploration of entrepreneurs and makers, a project that folded nicely into work being done in other parts of the company. My group at Intel had just started to develop its first maker-targeted product, Galileo, and stakeholders were interested in understanding more about technology makers and engineering entrepreneurs so that the company would be better able to market to and design for them. I proposed an exploratory research phase during which I would visit maker spaces, hacker spaces, and accelerators. This was a short, inexpensive research project, incurring only travel costs, so it was not a hard sell.

I had done some reading about the Maker Movement and understood that this was a contentious space, pitting large corporations against the little guy, and makers against hackers. Initially, I bought into the rhetoric of the movement—that it had the potential to shake up the world order through a democratization of production. Anybody would be able to be an inventor, bringing his or her invention to the market.

As I delved into this ethnographic exploration, talking to makers, hackers, and entrepreneurs from around the globe, however, I came to the realization that the movement was a reification of the status quo in the tech industry. Most makers/hackers were middle class, educated men with the luxury of time to tinker. Luckily (and unusually), two women served as my guides into this new culture, so I nudged around the topic of gender with them. They confirmed that the movement was largely a boys’ club for the “haves,” not the “have nots.” How then, I wondered, could this phenomenon be considered democratization of production when so many people were inadvertently excluded from the conversation?

In the interim, my group’s focus had shifted, and it became clear that I would no longer be able to continue the work I had started. But a colleague in another group offered to lead a next phase of maker research focused on girls and women, and luckily, I was able to participate on the research team. In a project we called MakeHers, we sought to understand how women and girls who were engaged in technical making came to it, and if and how they identified themselves within “the movement.” We hypothesized that women came to technical making from a different angle and identified differently than their male counterparts, hypotheses that were born out by our research.

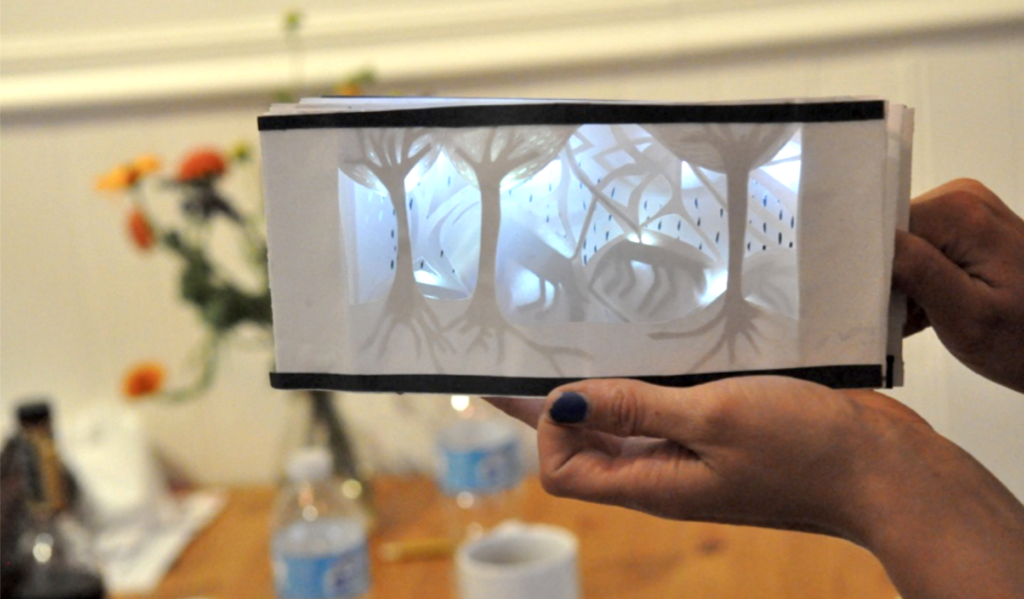

Technology-enhanced paper set design model created by a woman who had come to tech making through theatrical production. A high percentage of women come to have an interest in making with technology through the arts.

Did MakeHers move the needle at Intel? It did, and its influence was amplified by a fortuitous coincidence: The company was being publicly challenged to take on the social politics of gender for an entirely different reason. Our public report5 was released on the heels of Intel’s “gamergate” fiasco in October 2014,6 and shortly after that Intel announced, to much fanfare at CES 2015, an ambitious goal of increasing gender parity in the ranks of its technical staff. Intel also put money into creating more opportunities for girls to engage in technical making and supporting women in secondary and higher education.

Although it is impossible to measure the influence the MakeHers project has had on the company’s strategy with respect to gaining gender parity, it has continued to inform and influence organizations inside and outside of Intel. Within Intel, I have been called on numerous times to consult with Intel colleagues working on related topics. The report itself has had an extended life as a public relations piece, and my research partners have socialized the work widely independent of me. I have continued to consult on the development of new maker spaces that would be more welcoming and accommodating to the needs of girls and women outside of the company, including spaces in libraries and universities. The success of MakeHers encouraged me onward in my quest to do socially meaningful work.

ChildsPlay

During work on MakeHers I began another project that focused on smart toys and games. I developed a smart toy landscape and began working with others around Intel who were trying to develop smart toy prototypes. Right away I saw that nearly all of the smart toy ideas were likely to interest boys more than girls. Not surprising, since nearly all of the people involved at that point were men, and mostly engineers.

One of the first joint activities the team (a collection of engineers, business strategists, interaction designers, and researchers) engaged in was a brainstorming session. During that session, the two women in the room suggested that we should be more inclusive. How will girls ever develop an interest in technology if they are never exposed to it at a young age like their male counterparts? Initially, and to our surprise, several male participants pushed back, citing the interests of their own daughters as proof points that girls were not excluded from technology play. We pointed out that not all girls had engineer parents, and that perhaps their families and experiences were not typical. The engineers were working in a vacuum; they had no expertise or research-based knowledge related to kids and play beyond their own experiences as children or with their children.

As we continued to develop ideas and narrow the scope of project work, gaps in our knowledge became increasingly apparent. So I proposed a global study of play, which came to be known as ChildsPlay. A colleague from Intel Education expressed an interest in joining me on this project, and others expressed an interest in supporting our work with budget. In spite of the expressed interest, and willingness to support the work with budget, in the end, getting the work off the ground and funded was a real struggle because the company was undergoing widespread organizational transitions, and budgets for research had been frozen or eliminated altogether.

We had an overall vision of the work and a clearly laid out proposal, but each step of the way we had to prove ourselves and the value of the work we were doing to our paying sponsors. We did it in phases, starting with a pilot study, and after each phase had to seek approval to move to the next step. In the end it took us much longer to complete the work than it should have.

ChildsPlay was a large multi-modal research project funded by multiple organizations. We collected both survey and in-home observational data in the US, Germany, and China for children ages 3 to 18 and their parents. Our official goals were to develop a multi-cultural understanding of current and trending interests of kids and parents and their attitudes about the changing role and landscape of technology in play. We also wanted to understand the broader cultural contexts of play: play behaviors in different cultural and physical environments, what analog and digital play kids engaged with, and the breadth of toy collections.

Some of the objectives were directly related to design of the types of smart toys Intel was developing. A less publicized objective of the research was to fully understand how gender revealed itself in play, toys owned, and associated parental values and roles in shaping interests in their children. This aspect of our work had not received a warm response from stakeholders during the proposal phase, and so we decided not to emphasize it. We felt an indirect pressure to not be controversial, and therefore did not make this goal explicit in our circulated proposal, although it was top of mind from the perspective of the research design.

Pink and pretty dominate the narrative of girls’ toys. Upper photos: every girl in the US and Germany and a play kitchen; many fewer boys have these. Lower photos: LEGO and Duplo for girls beauty and princess themed.

ChildsPlay revealed significant cultural differences in attitudes and beliefs around the value of play, and also remarkable disparities between the play of boys and girls. We were able to provide evidence that the toys that children play with at a young age influences their interests in later childhood, strengthening our argument that providing young girls with toys that teach skills and knowledge that are prerequisite to developing an interest in STEM in later childhood should be of high interest to the technology and toy industries if there is a serious desire to bring eventual parity in representation of women in technical fields.

This project has enjoyed some success within the company and has moved the narrative on development teams away from being US and male centric. In addition to giving multiple readouts at company-wide forums, we have worked directly with product teams in a consulting capacity. The gender message has had a mixed reception, getting positive responses from product development teams and some pushback from engineering forums where we have presented.

We have found that telling the gender story in isolation from the broader research is more likely to draw criticism than using the gender story to frame the cultural story of the research. Product teams have used the research for developing design personas, informing design, and for making strategic decisions. The research has also given Intel credibility with potential industry partners, demonstrating our knowledge of play. People who had no interest in discussing inclusion when it comes to tech toys are now thinking about how to “get” girls and boys interested in STEM.

Due to organizational changes at Intel, this work has not been as fully socialized as it might have been otherwise, but a number of people have continued to draw upon it as they envision the future of play. The work is leaving a mark.

Research and Design Are Inherently Political Activities

Both MakeHers and ChildsPlay are examples of research and subsequent design for good—they serve as counter-influences to long-term unintended consequences of marketing technology and technology-making to boys and men. As social researchers working in industry, we need to do more than inform design of this thing or that thing; we need to seek opportunities to subvert, to be radical, to change corporate, industry and social narratives, if only an inch at a time. Doing this is not for the faint of heart, however, as the messages we bring and the work we do are not always as valued or welcomed and it can be difficult to find support.

Some people believe that using research as a means to political ends is wrong, or biased. But both research and design are inherently political activities; they always express a point of view, and as such, there will always be pushback from those who wish to conserve the status quo. Ultimately both research and design are about making change, sometimes small change and sometimes big change. Researchers seek to discover undiscovered patterns that will move thinking forward. Designers seek to create something new that will change the way people see and live in their worlds

As researchers, we need to embrace our power as political actors and influencers, even when it’s limited, especially in a time where technological advancement runs at breakneck speed. We need to do good, and we also need to help mitigate unintended negative consequences of the technologies we help to develop. We must not shy away from expressing points of view on any of the tough topics of our time—from poverty, gender, and environment, to privacy or corporate hegemony. To do this, radicals in cubicles need to support each other professionally, share stories of our successes and challenges, and build strategies for doing good in the face of organizational barriers.

Notes

1. Intermedia: A Case Study of Innovation in Higher Education. Final Report to the Annenberg/CPB Project on A Network of Scholar’s Workstations in a University Environment: A New Medium for Research and Information, with William O. Beeman et al. Providence: Institute for Research in Information and Scholarship, Brown University, 1987.

2. “The Littlefield Research Project,” with G. Bader, J. Larkin and K. Anderson. Research Program in Education, Culture and Technology, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. 1989.

3. “Hypertext and Pluralism: From Linear to Non-linear Thinking,” with W. O. Beeman, et al. Hypertext ’87, 1987.

4. Why Things Bite Back: Technology & the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, by Edward Tenner. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

5. “MakeHers Report: Engaging Girls and Women in Technology through Making, Creating, and Inventing.” 2014.

6. “Intel Pulls Ads From Site After ‘Gamergate’ Boycott,” by Nick Wingfield. 2014.

Anne McClard is a Senior Researcher in the Data Center Group at Intel Corporation. She holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from Brown University, where she did seminal research on the emergence of the World Wide Web, and since then has worked at Apple, US WEST/MediaOne Broadband Labs/ATT Broadband Labs, and Qubit Technologies. In recent years, Anne has focused the emergence of the Internet of Things, the maker movement and topics related to wearables and physical computing. Most recently, she led a global study of children’s play as it relates to the future of toys. Throughout her career, she has sustained an interest in gender issues in academia and technical industries. At EPIC2017 Anne will co-host the Salon Design in a Post-gender World.

Anne McClard is a Senior Researcher in the Data Center Group at Intel Corporation. She holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from Brown University, where she did seminal research on the emergence of the World Wide Web, and since then has worked at Apple, US WEST/MediaOne Broadband Labs/ATT Broadband Labs, and Qubit Technologies. In recent years, Anne has focused the emergence of the Internet of Things, the maker movement and topics related to wearables and physical computing. Most recently, she led a global study of children’s play as it relates to the future of toys. Throughout her career, she has sustained an interest in gender issues in academia and technical industries. At EPIC2017 Anne will co-host the Salon Design in a Post-gender World.

Related

Making Change: Can Ethnographic Research about Women Makers Change the Future of Computing?, Susan Faulkner & Anne McClardd

Radical Design and Radical Sustainability, Thomas Wendt

The Politics of Visibility: When Intel Hired Levi-Strauss, or So They Thought, Rogerio de Paula & Vanessa Empinotti

Commit to Critical Understanding, The EPIC Board

Something More Persuasive than Fear, Ed Liebow

0 Comments