Despite constraints on face-to-face meetings and social distancing policies under COVID-19, with the help of online tools, Brandnographer successfully conducted a series of online activities to facilitate stakeholders from different age and background to immerse themselves in situated scenarios, then to design and visualize their ideal public services in the future. This paper discusses how a participatory approach and design thinking framework have helped the researchers and decision makers collect thick data from the service users, transform user insights into prototypes for reiteration and concrete design principles. On the other hand, how the blurred identities in between observers, participants and designers have stimulated discussions and design possibilities by supplying real-life scenarios and evaluation on solution feasibility.

INTRODUCTION

Anthropology and ethnography have long been used as a research tool to understand and capture past and present cultural experiences (Lueck and Avery 2020). Cultural foresights and intriguing queries for the future are not always channelized into future forecasts or suggestions that bring impactful changes, however,

“As ethnographers, it is not enough to describe social reality, to end a project when the last transcripts and field notes have been analyzed and written up. We must find new ways to engage and collaborate with our subjects (both human and nonhuman). We need better ways of turning our descriptive, analytical accounts into those that are prescriptive, and which have greater import in society and policy. We may do this by inhabiting narratives, generating artifacts to think with and engaging more explicitly with the people formerly known as our “informants” as well as with the public at large.” (Forlano 2013)

In this consultancy study, we were tasked to attain two goals for the public service provider: firstly, to employ a participatory design approach to engage with citizens in the project to help to government become more citizen-centric; secondly, based on our knowledge on the users, derive, anticipate future usage scenarios, and create prototypes that fully represent their needs and solve their daily problems correspondingly.

Through sharing our experiences and processes of designing our research methodology, this paper shall discuss how Brandnographer had helped public users, as well as our internal stakeholders visualize ‘a possible, preferable future for the group’ (Robert 1999, 2, as quoted in Strzelecka 2013), with the help of deploying the 4-stage double diamond design model and 5-step design thinking process. This paper also discusses how the participatory approach had broken static relationships in between observers and participants, added dynamics in between informants, researchers and decision makers, and inspired a series of educational sessions through discussions, interactions and co-creation (Hemment 2007).

CONTEXT OF HONG KONG

This project carries significance in two dimensions: 1) innovative qualitative research methodology emerging under COVID-19, 2) shift in power under the evolution of urban governance style, and the research project being set in Hong Kong in such unstable times has added further prominence its implications and impacts.

Journey towards digitalization

After over a year of home-officing and online shopping, digitalization and mobile-first experiences have inevitably become global trends steering the retail service and experience designs. Moreover, Hong Kong people in general have been more reluctant to converting to digital-only experiences when compared to other Asian regions. Unlike their Chinese counterparts, Hong Kong people tend to be slower in adopting to the use of digital tools in their everyday life. Even with Internet penetration rate as high as 89.4% and a smartphone penetration rate of 75%, up till 2021, Hong Kong has a relatively low e-commerce transaction rate – at only 36%, less than half of China – 76%, while India has 46% and Singapore is at 42.3% (J.P. Morgan 2021).

Under the Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint first released in 2017 (Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint 2020; 2017), as part of the city’s Chief Executive Policy Address at the time, public services in Hong Kong are currently undergoing digital transformations, in aim of bringing more offline public services online, improving the city’s efficiency, resilience, mobility and competitiveness. The public service provider is backed by the Smart City Blueprint to digitalize their infrastructure and services, streamline their work processes, and optimize users’ digital experiences in a way that is inclusive and comprehensive for users from all ages and levels of technology savviness.

Newfound devotedness in local issues

Besides prevailing trends and demands for digitalization, the project also takes place amidst strong sentiments and needs for democratization and bottom-up participation in policymaking and decisions regarding public services. In the past decade, localism had risen drastically along with series of protests expressing deep-rooted satisfaction towards the ruling party and government office, as a claim for Hong Kongers’ rights to democracy and universal suffrage since 2012 anti-National Education protest and Umbrella Movement in 2014 (Veg 2017, 324-325). In the District Council election in 2019, over 70% of Hong Kongers had taken part in the vote in contrast with 47% in 2014 after Umbrella Movement (Bradsher, Ramzy and May, 2019), and as a result, 389 pro-democrats were elected, doubled of the 124 seats they occupied previously. The surge in public participation in politics and public affairs recently had led way to adoption of a citizen-centric approach towards public services and facilities redesigning.

Communication of citizens’ views on public services was mostly one-way, like online/ offline questionnaires on existing services. Citizens were seldom consulted as well-informed decision-makers, and values of their lived, first-hand user experiences were easily overlooked. Civic workshops being carried out at the planning stage of a government project, is thus a refreshing new, hands-on alternative that emphasizes citizens’ knowledge, as well as their original ideas and designs, which also have become an empowering experience for the public to converse with policymakers or decision makers for public services.

In parallel with the rise of localism, a handful of creative community-based initiatives promoting civic participation and empowerment have emerged in the past 10 years among local communities, due to the dedications of social innovators, local creative design studios, urban planners, architects, and artists in Hong Kong. Their people-centric lens honor power and wisdom of the people, and have proved to bring impactful, practical, and socially inclusive solutions. The influences and inspirations their exemplary projects brought have not only promote social inclusion and cohesion in the city but had become bedrock for the government service provider to partner with Brandnographer, in translating knowledge from the people into their service and facility design strategies.

RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY DESIGN

Design Thinking and Double Diamond Model

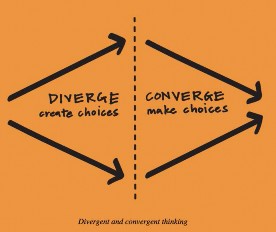

In the study, Brandnographer had employed a Design Thinking approach and The British Design Council’s Double Diamond model (British Design Council, 2019) for the public service’s system service and venue design. A design thinking methodology is a creative approach to disrupt the current ways of doing things, to make institutional changes that are desirable by users, viable in problem-solving, while feasible for the people who execute. It first ‘diverges’ – allows exploration of all possible choices under contexts and circumstances, then to compare similarities and differences – ‘converge’ and narrow down to the feasible, actionable solutions (IDEO, 2021). It was also through this process, members of the public played the role of policymakers for a couple of hours, had hands-on experiences brainstorming, discussing, and designing solutions for their beloved services.

Figure 1. Converge, Diverge Design Thinking model by IDEO; Photograph ©2021 IDEO

Prior to the engaging workshops, in order to build deep understanding into users’ needs, define questions precisely and accurately, for guided, and more focused discussions, Brandnographer followed the Double Diamond Model to ensure user insights and problems were repeatedly tested and iterated, before collaborating and co-creating new solutions in online and offline workshop sessions.

Figure 2. Double Diamond, Design Thinking model by British Design Council; Photograph ©2019 British Design Council

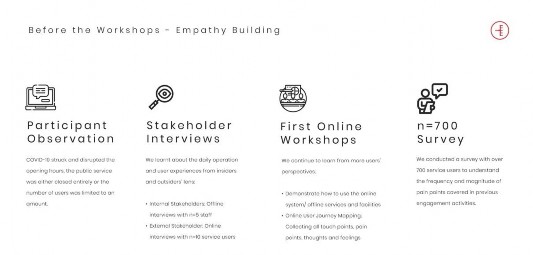

Stage 1: Discovery

As the first stage of the project, Brandnographer team has planned for participant observation and a series of stakeholder interviews to collect and familiarize with as many variables affecting how users approach the current public service and infrastructure, as possible. Including the frontend and backend equipment in every one of their physical service centers, as well as the online system and mobile apps, where users access their databases via a search engine and make reservations for facilities.

To learn about the context of the services and their users, Brandnographer team observed and learned from their internal and external stakeholders. Internal stakeholders including the service provider’s managerial and frontline staff, while their external stakeholders were citizens of Hong Kong, covering a wide range of people at different age, levels of familiarity towards technologies, frequencies of using the service, their pattern usage, goals and needs. For example, some users go there every day, but prefer to talk to the staff because they enjoy the personal contact and they do not need to experience ‘trial and error’ when interacting with the facilities. Whereas some users visit the center once or twice a week but are more comfortable with using self-service options.

However, with COVID-19 struck and disrupted the facilities’ opening hours, on-site fieldwork was not possible at the beginning. During first stage in-depth interviews, online meeting tools’ functions were leveraged for respondents to relive and demonstrate their daily routine, activities, and patterns on the current service systems. Nonetheless, comparing with face-to-face ethnographies, the lack of on-site observation had made understanding of user paths, user’s epistemological experience on space, and interactions with facilities far less precise.

Stage 2: Define

Under social distancing restrictions, in order to visualize and pinpoint service users’ pain points, day-to-day frustrations and bottlenecks encountered by users, the team made their first attempt using online collaborative tool in the first online co-creation workshops. When designing workshop tasks and activities, the team aimed at recreating co-creation with same levels of user involvement and engagement, like a face-to-face workshop. On the online whiteboard, each step of approaching a service was outlined in details as key touch points. Users’ real-life scenarios, motivations and pain points were collected and mapped out based on the user journey map framework (see Figure 3) and moderators’ guided discussions.

The online whiteboard allows users to communicate their ideas easily via words, drawing, and sharing of multimedia materials (see Figure 4), providing handy tools for participants to visualize their thoughts, follow other participants’ sharing, build on each other’s inputs simultaneously which is instrumental in drawing focuses on the reiterated pain points, conduct a more focused discussion. But the co-working performance was at the same time confined to participants’ intuitions and access to stable Internet connection. To resolve such limitation and distractions, public participants’ hands-on involvements on the whiteboard were kept to minimum and the outcomes became heavily relied on moderator’s iterations and assistant moderator’s abilities to capture the gist of discussions.

Having moved workshops from offline to online, one of the major concerns was that the indirect human contact behind computer screens and lack of direct connections among participants and moderators limit the level of participation and devotedness. While at the same time, such anonymity benefited our clients to take the front row in observing and joining the small group discussions, empathize with their service users.

Figure 3. User Journey Mapping Framework; ©2021 Brandnographer

Figure 4. Online Collaborative Tool demo; Image ©2021 Brandnographer

Figure 5. Stage 1-2 Empathize with users, define problems, and focus questions. ©2021 Brandnographer

Following the user knowledge collected in Stage 1, Brandnographer team also did a survey to understand the frequency and magnitude of user pain points, to concentrate on problems that more users resonate to and feel more deeply about. The rigorous inference in stage 1 analysis was crucial to define problems, set the scene, to brainstorm actionable solutions and help the team derive insights that ultimately be transformed into system and venue design recommendations.

Stage 3: Development

With the defined problems in Stage 2 in mind, the team proceeded to ideation and designing, developments of solutions via a second set of co-creation workshops, which again, engaging both internal and external stakeholders. The essence of employing the design thinking process is to build user-generated solutions based on their personal experiences, leveraging on users’ knowledge and creativity, to explore approaches that are truly impactful and sustainable for the users. With our experience from the first set of workshops, we entered this stage with two big questions:

- How to turn laypersons with different levels of tech savviness and experiences with the service into designers, to co-design prototypes for the system and the center’s interior and physical distribution of facilities?

Participants’ levels of interaction and participation heavily rely on the virtual tools, and thus, the choice of appropriate platforms and modes of participation for the design activities was key. Many participants had observed and collected flaws from the current services, but the challenge remained on how to channelize their pain points into positive creative energies is highly dependent on their abilities to experiment with concepts effortlessly. The team must design instruments and stimuli that balance easiness to use and a certain level of sophistication, enabling and motivating participants to communicate and test their ideas well, so that the end output could be eventually adopted in designs in real life.

- How to guide participants to envision the future, when designing the prototypes?

One of the main goals of this project is to design for all service users, and design ahead for the future. Moreover, to understand what users need to enhance their service experience in the future systems, moderators must carefully bridge the pain points from the presence with future potential user scenarios and needs, to translate current user knowledge to future adaptation. The team carefully designed stimuli based on thorough understanding in the core of service functions, as extracted from Stage 1 ethnographic research.

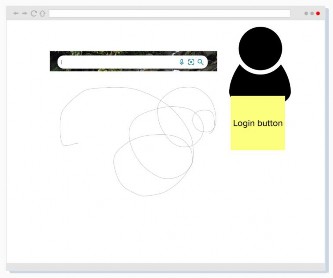

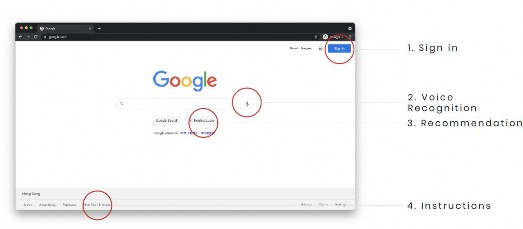

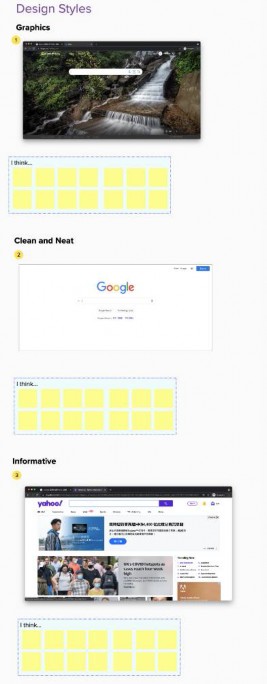

Substantial amount of design stimuli was used to help participants to imagine the future, to reimagine the present services, it is particularly effective for preparing for anticipatory ethnography, and creation of future innovations. In order to produce such valuable results, the stimuli must be able to i) precisely and concisely grasp the key objectives of the service provision (see Figure 6), and ii) demonstrate and actualize future possibilities of the services, expand participants’ imaginations (see Figure 7).

Figure 6. Deconstructing a system interface. What are the key objectives for this service? What are the key elements to be kept and enhanced? Search Engine and Landing Page ©2021 Google

In our workshop, we prepared our participants with design references from different angles, to ensure we collected their feedbacks from all key performance parameters for creating a smooth and comfortable user journey, they are namely, design style, key functions, steps and sequence. These stimuli inspired participants’ sharing on current experiences and their projections of their ideal interactions with a hypothetical, ideal interface in the future at the same time. As they discussed the hierarchies of functions and compared the effectiveness of the stimuli’s designs, a reiteration process travelling back and forth empathy building and solution ideation was resulted.

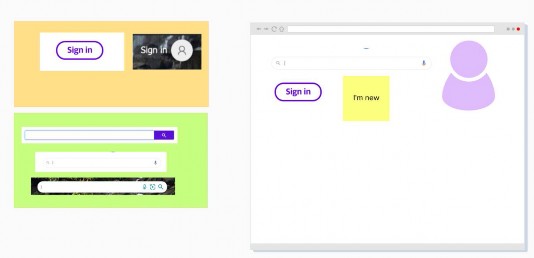

From the very beginning of this set of workshops, moderators strongly emphasized the goal to ‘design for all, design for future’, driving our participants towards a future orientation and vision beyond their personal benefits. Despite the lack of design foundation amongst our participants, the workshops were designed carefully surrounding the 2 major questions depicted above. The foolproof prototyping toolkits designed began from providing layperson participants with the accessible choices, selections of inspiration board and design elements that clearly projects future possibilities, a set of simplified and guided steps for a structured creation process, they were able to transform into system and interior designers for just one day, to complete an accelerated prototyping journey.

Figure 7. Which is a better design style for the search engine? Why? How would you approach No. 1? Anything missing from it? ©2021 Brandnographer. (top) Screenshot from Bing landing page, the search engine ©2021 Bing; (middle) Screenshot from Google landing page, the search engine ©2021 Google; (bottom) screenshot from Yahoo! UK landing page and search engine ©2021 Yahoo! UK

For example, in the system interface design, it was through discussions on each function’s design, or its design style, where we moderators helped magnified every important touch point and together with other participants and observers, uncovered and learnt how users perceived, interpreted the details, approached, and interacted with these interface elements (see deconstruction sample in Figure 6 and comparison in Figure 7). Also, through their preferences and justifications on the provided options, we all learnt more about how different stakeholders would have imagined their ideal pathways and their rationales behind. The step-by-step guided discussions on the deconstructed features and functions had paved the way and steered participants towards clear focal points: What are the ultimate purposes of this service? Which function or feature is the most valuable to be optimized, to achieve such service objective? And secondly, how do my peers perceive and prioritize these elements, and thus, how may I design to fit their needs, habits, and intuitions?

Figure 8. Let’s build the prototype! Actualizing and experimenting ideas to find the optimal solutions, through discussing and stitching elements into one coherent interface. Image ©2021 Brandnographer

After collecting the diverging ideas, sharing of personal experiences, mutual learning and empathizing, small groups of participants discussed and put together the different designed elements to explore varieties of solutions and test their feasibility. The combination of highly collaborative work and anticipation for future experiences came together as a preliminary prototype for the system and service center (see sample canvas on Figure 8). In the end, each group had designed a version of solution that is reflective of their habits and behavioral pattern, address their pain points, and is also meaningful and impactful to them.

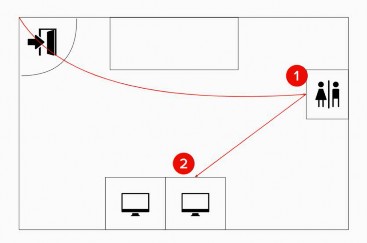

Figure 9. Interior and new facilities distribution design follows a similar pattern as system user experience design. First, learn different users’ habits of using current service (red route). Illustration ©2021 Brandnographer

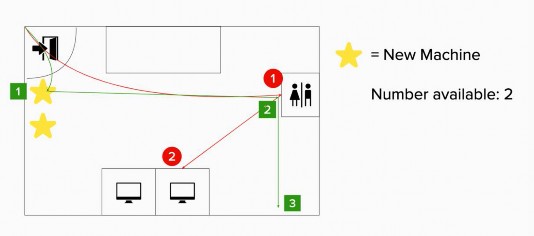

Figure 10 Introduce and explain new machines to be added to future services, then allow users to explore the best distribution solution (green route), test and discuss a common approach within the group; Illustration © 2021 Brandnographer

Stage 4: Delivery

Subsequently, the Brandnographer design team had derived key insights from the elaborated series of discussions, found the common converging points and created versions of interactive prototypes, especially for the system interfaces. As the social distancing policies relaxed in May 2021, the mock-up options were put up in offline mobile experiential booths for user to click, scroll, test, and compare. Over the course of 20-minutes’ short interviews, the team was able to observe service users’ interactions with the mock-ups, evaluate the value and validate effectiveness of these user-generated prototype solutions and reiterated general user’s core needs again. Over 90 responses were collected from across 5 outlets around Hong Kong.

The user scenarios and insights elicited were used to further refine prototype designs, help narrow down and investigate roots of problems in greater depths, and at the same time to enhance, and optimize design recommendations for the service provider’s future service and venue designs.

EVALUATION, LEARNINGS AND OBSERVATION FROM THE NEW APPROACH

“We highly appreciate the chance to listen to citizens’ ideas and views.”

–Chairman to the project’s Task Force

The open, highly interactive and conversational public engagement was refreshing and innovative for our client, as well as their public service users, not only because large part of it was held online, but the engaging interactions where the decision makers of the service were able to take part as an active audience, even to experience the designing process with them. Although the online format posed limitations, at the same time, this has injected new perspectives into innovative ways of designing and conducting online ethnographic work.

Aside from attempts on online collaborative platform, Brandnographer team also explored different methods to guarantee their level of interest and engagement, to avoid loss of attention, as a result to the restricted human touch. In this project, Brandnographer team attempted to reconnect participants with the actual outlets and facilities, especially after months of their closure, through virtual tours around panoramic shots of the center interior. Even though first-person spatial experience is irreplaceable, the extensive application of immersive experiential tools helped participants recall their routines and practice. In group discussions and sharing, being immersed in the ambience had taken them back to their memories at the centers almost immediately, even enabled them to pinpoint some spots and corners specifically and explain their interactions in greater details. Digital tools should not solely be perceived as more convenient and cost-effective alternatives to offline fieldwork, but there should be more potentials to their functions to be explored, to help enrich and better prepare us and our respondents in our research work.

After COVID-19, we can see that a higher conversion rate towards online platforms, and digital ethnography will continue to grow as part of our new normal. It is high time to investigate how digital instruments could help optimize aspects in our studies, like the how to materialize users’ abstract ideas, or to utilize the handy online tools to disrupt the roles of respondents, researchers, social, service or product designers.

Actionability

In ethnographic research, it is often that studies focus on recording present experiences and the past or detecting interests and arising trends for the future. Users’ needs were gauged but their wants and expectations may remain abstract. Given that a prototype model usually takes long time to prepare, not a lot of ideas could be actualized and put to test within a research study. Moreover, leveraging on online resources, like no-code platforms that simplifies complex coding and programming, or borrowing existing multimedia files and snipping tools, systems and design ideas could be created within minutes’ time, accelerating idea validation and reiteration process, proving their feasibility and impacts and refining them within shorter period.

In the second set of workshops, under a meticulously planned framework, low-fidelity wireframe prototypes emerged from an empty canvas within 1.5 hours, where concrete visualizations of ideas of ideal user paths, priorities of functions and message were created, as well examined, tested, and enhanced in the same space. As concepts were experimented and shared on a blank canvas, the contradicting or incoherent steps and elements would have already been detected, discussed and eliminated during the workshops, eventually, increasing the actionability and practicality of final outcomes.

In addition, riding on the era of user-generated content, younger participants’ abilities to operate and express their ideas in word, media or other creative forms might also be more efficient. Prototypes created by citizens, is undoubtedly strongly representative of their benefits. Nonetheless, to facilitate a productive anticipatory ethnographic session requires solid bedrock, long line of preparation of stimulus for before and during the session, in order to immerse participants in the conversations and steer productive discussions towards the focused questions more quickly and efficiently.

Shift in Power between Policy Makers and Citizens

In engaging participatory design sessions, such as our second set of co-creation workshops, participants were provided were delegated the role of designers to control the creativity power, create solutions and outcomes that in turn, guide policy makers’ planning. The step-by-step toolkits designed by Brandnographer team empowered participants to go beyond sharing of pain points, but to extend their problems to potential solutions, communicating their expectations to the decision makers directly in these engagement sessions, with concrete examples and suggestions in forms of wireframes. As mentioned, as Hong Kong is undergoing a roaring sense of localism and policy decision-making, a bottom-up, participatory model, or a model that highlights user/ citizens’ voices, their angles and benefits has become crucial for citizens to feel more democratic, have stronger sense of control and grasp over their livelihoods.

On the other hand, roles in between researchers, participants, our observers were also reshuffled. Besides the Brandnographer team, the end client had formed a Task Force team to steer the project and participated in the engagement activities as observers. Especially when they joined the online activities, they were able to listen to full discussions, understand user sentiments first-hand, even to follow their train of thoughts to their creative outcomes. Having decision makers to empathize with users through participating in ethnographic observation was a crucial and powerful first step to initiate and sustain change management in long term, because the Task Force would go on to be the drivers of new system and facility design, putting these user insights into implementation. And it was evident that being able to participate in the conversations, even ask questions directly when in doubt, the high levels involvement had created deep impacts to these decision makers. Actual user quotes and realistic user scenarios were etched in their minds as they had heard the users’ entire thought process and stories, they became more motivated to design around users’ needs, motoring the public service’s change management process from a psychological level.

Limitations of the Methodology

Regardless of various options of digital tools emerging in the market, respondents, participants’ tech savviness and device ownership remain to be a barrier to access online research or collaborative platforms, which restricts the scale, the nature of research, and participants’ levels of engagement. Close observation of participants’ willingness and tech savviness is key to ensure their motivations to participate and, in the end, the quality of outcomes. Hong Kong citizens have high smartphone ownership rate, but forms of activities and content were too, limited to their screen sizes, and reluctance to use computers outside of working hours. This has made online collaboration and creative works more difficult. In the foreseeable future, online ethnographic tools will need to balance convenience and functionalities to better serve the arising digital fieldwork demands.

The series of workshops did not only open up a platform for understanding and co-creations, but also where the power and roles of decision makers, researchers, designers and informants were blurred, injecting new dynamics and outcomes in research activities. We believe that this successful case has proved public engagement activities could also deliver practical design strategies that proves to enhance user experience and highlight human centredness. It is hoped that this has opened up more opportunities for decision makers from public services to adopt a more open approach towards immersive and engaging public consultations in the future when anticipating needs and designs for future services, and to be able to truly initiate change from empathizing and understanding the users, in a bottom-up direction.

Lok Yi Lee, Annabelle (annabelle.lee@brandnographer.com) is a Hong Kong-trained cultural anthropologist, specializes in ethnographic and user experience research. In addition to her academic trainings, Annabelle has experiences with design thinking workshops facilitation and design, consumer insight and cultural analysis, project management and coordination in several local and international projects.

Lyra Jiang is a seasoned researcher with background in Chinese Language and Literature and a master’s degree in Applied Cultural Analysis, Lyra’s specialization in cultural linguistics gave her a competitive edge in gaining cultural insights with the use of qualitative research supported by quantitative data.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – This work was produced by Annabelle Lee, with framework and guidance from Lyra Jiang. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of Brandnographer Co. Limited or the public service provider.

REFERENCES CITED

“E-commerce Payments Trends: Hong Kong.” J.P.Morgan website. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://www.jpmorgan.com/merchant-services/insights/reports/hong-kong

Bradsher, Ramzy and May. 2019. “Hong Kong Election Results Give Democracy Backers Big Win.” The New York Times website, Nov 24. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/24/world/asia/hong-kong-election-results.html

“Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint.” HK Smart City Blueprint, December 2017. Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.smartcity.gov.hk/modules/custom/custom_global_js_css/assets/files/HongKongSmartCityBlueprint(EN).pdf

“Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint 2.0.” HK Smart City Blueprint, December 2020. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://www.smartcity.gov.hk/modules/custom/custom_global_js_css/assets/files/HKSmartCityBlueprint(ENG)v2.pdf

Veg, Sebastian. 2017. “The Rise of “Localism” and Civic Identity in Post-handover Hong Kong: Questioning the Chinese Nation-state”. The China Quarterly 230: 323–347. doi:10.1017/S0305741017000571.

English-Lueck, J., & Avery, M. Futures Research in Anticipatory Anthropology. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Retrieved 12 Jul, 2021. https://oxfordre.com/anthropology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.001.0001/acrefore-9780190854584-e-14.

Forlano, Laura, 2013. “Ethnographies from the Future: What can ethnographers learn from science fiction and speculative design?” Ethnography Matters. September 26, 2013. Accessed March 27, 2021. https://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2013/09/26/ethnographies-from-the-future-what-can-ethnographers-learn-from-science-fiction-and-speculative-design/

Strzelecka, Celina. 2013. “Anticipatory anthropology – anthropological future study.” Prace Etnograficzne 2013, tom 41, z. 4, s. 261–269doi:10.4467/22999558.PE.13.023.1364

Hemment, Julie. “Public Anthropology and the Paradoxes of Participation: Participatory Action Research and Critical Ethnography in Provincial Russia.” Human Organization 66, no. 3 (2007): 301-14. Accessed July 12, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44127379.

Yu, Adam. 2018. “初探雙鑽石設計流程”. Medium. Accessed 26 March 2021. https://medium.com/@y3vu060312/%E5%88%9D%E6%8E%A2%E9%9B%99%E9%91%BD%E7%9F%B3%E8%A8%AD%E8%A8%88%E6%B5%81%E7%A8%8B-ux-notes-5fcf4b4cae6f.

IDEO. 2021. “Design Thinking Defined”. Accessed 26 March 2021. https://designthinking.ideo.com/.

Design Council. 2021. “What is the framework for innovation? Design Council’s evolved Double Diamond”. Accessed 26 March 2021. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/what-framework-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond.