Cultivating resilience while navigating uncertainty is crucial for refugees. In the Netherlands, after receiving asylum and the right to work, refugees are often urged to adapt or evolve in hopes of successfully integrating into the Dutch economy. How do forced migrants who pursue work in creative enterprises help us rethink the relationship between forging new lives and uncertain futures? In this paper, resiliency of refugees is presented as a process of creative performance and experimentation. Efforts taken by refugees to explore, or ‘self-potentialize’, new future creative pathways suggest that resilience is overly simplified when defined as a pursuit of resistance to integrate and conform into established creative industries. The stories of two refugees living in Amsterdam showcase how resiliency is future-oriented, processual (Pink & Seale 2017), and connected to the preservation of one’s ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013). ‘Future-making’ is embedded into their creative pursuits and weaved into their ongoing journeys of personal and professional development. Ethnographic inquiry into the perspective of refugees pursuing work in the creative economy sheds light on the complexities and nuances of rehearsing alternative imagined futures. Keywords: imagined futures; uncertainty; refugees; creative performance; aspiration.

INTRODUCTION

In 2022, the future of refugees has once again become an urgent topic of global concern. Ongoing danger due to either war, violence, or risk of persecution threatens the lives of millions forcing them to seek shelter and safety across international borders. The Russian invasion of Ukraine led to 2.5 million residents fleeing the country to neighbouring European states and other parts of the world within a span of two weeks. The situation in Ukraine was described as “the fastest growing refugee crisis in Europe since World War II” (@FilippoGrandi, UN Refugee Agency Commissioner, Twitter, March 16, 2022), heightening the significance and visibility of forcibly displaced people around the world. The plight of (non-Ukrainian) refugees’ migratory experiences has been a longstanding topic of academic research, while often positioning these displaced populations as the subject of case studies regarding severe mental health concerns, medicalized trauma, economic development, and the reverberations of crisis. Yet, in a conceivably ‘post-covid-19 pandemic’ world, where corporations, organizations, and governments worldwide are aiming to relieve strategic indecision and illuminate paths forward, ethnographic inquiry into forced migrants’ perspectives sheds light on the complexities and nuances of imagining unknown futures. Those living with deep uncertainty in their daily lives, such as refugees, offer a route for ethnographers to view resilience as a mindset to anticipate and speculate the future.

In the Netherlands, asylum-seekers (those awaiting legal-status decisions) often endure an unpredictable amount of time to receive their residence permits and complete the asylum-seeking procedure. For many readers, this trying procedure alone might qualify asylum-seekers as suitable candidates to teach on the topic of resilience based on their ostensible ability to sustain and recover from unprecedented change (Balfour et al 2015). Even after receiving asylum and the right to work (referred to as ‘refugees’ in the Netherlands once legal status is obtained), refugees are urged to adapt or evolve in hopes of successfully integrating into the Dutch economy; either by means of heavily marketing their previous experience or upgrading their skills. Those who intend to integrate into specific industries, like the creative industries, are often met with resistance, financial pressure, and a lack of encouragement from government services aimed at assisting employment seekers. Due to these circumstances, the vocational aspirations of refugees are often given minor consideration relative to their legal status, safety, and general social welfare. Vocational aspirations can, however, offer an entry point to examine where and how refugees realize and actualize their desires for previously unimaginable (or possibly unattainable) futures prior to their forced migration.

Across the community of practicing ethnographers and social scientists in industry, policy, and academia, there are multiple definitions of resilience. In one extreme, resilience has been defined as one’s ability to “experience severe trauma or neglect without a collapse of psychologic functioning or evidence of post traumatic stress disorder” (Alayarian 2007, 1). The word ‘without’ in this definition is interpreted to emphasize the ability to endure and withstand. Within the EPIC community, resilience has been referred to as “the ability to learn, adapt and evolve in the face of adversity or changing conditions”1 – interpreted as a form of recovery, or even resistance. Resilience is often projected onto refugees, as a category of people who have typically undergone trauma, violence, and intense disruption in their lives. This viewpoint can be extended further to describe how their vocational aspirations and employment pursuits are typically seen from an etic (or “outsider’s”) perspective. Meaning that, because refugees in the Netherlands face discrimination, racism, and xenophobia – which positions them in economically disadvantaged positions and detracts them from finding employment opportunities (Van Tubergen 2006) – they are also likely to being viewed as “resilient”. However, what if resilience was thought of as something beyond one’s endurance, recovery, or pursuit of resistance? In this paper, I present the resiliency of forced migrants as a process of performance and experimentation, rather than a method of resistance against pre-defined integration processes and societal conformity.

Based on original ethnographic research conducted alongside predominantly Western Asian/Middle Eastern displaced migrants, this paper showcases how resiliency is future-oriented, processual (Pink & Seale 2017), and connected to the strengthening of one’s ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013). Two selected refugees’ stories highlight how creative performances are foundational forms of self-expression that allow experimentation with alternative futures that can be rehearsed and practiced. I argue that processual acts of ‘future-making’ are embedded into refugees’ creative pursuits and weaved into their ongoing personal and professional development oriented towards employment in the Dutch creative industries. This paper offers a partial answer to a larger ethnographic question, asking: how do forced migrants use creativity to intertwine self-expression and employment as a means of ‘future making’ while navigating uncertainty brought on by their precarious legal status in the Netherlands? In other words, how do forced migrants who pursue work in creative enterprises help us rethink the relationship between forging new lives and uncertain futures? Ethnographic inquiry into the economic integration journey of refugees pursuing work in the creative economy in the Netherlands offers a unique lens to understand the intricacies of navigating uncertainty and explore the process of imagining alternative and unknown futures once asylum has been granted.

Furthermore, this paper is a direct response to Panthea Lee’s EPIC2021 Conference keynote presentation which challenged how ethnographers engage with their respective corporate stakeholders to speculate and imagine the future. In her talk titled “Exiting the Road to Hell: How We Reclaim Agency & Responsibility in Our Fights for Justice”, Lee suggested that ethnographers must include the perspective of artists, makers, and creators into the folds of ethnographic research “to amplify the voices of those who possess moral clarity and courage” and “radical imaginations” to ensure that the next version of reality – our collective future – is indeed different than the version in which we are living in now (Lee 2021). While it is debatable who is in possession of “moral clarity”, Lee’s categorical description of who these creative practitioners are is clear and was intentionally considered during the design of this research. Through the analysis of creative practices, this paper argues that pockets of refugees in the Netherlands are indeed finding their “voice” to express their radical imaginations of the future (Hirschman 1970, in Appadurai 2013). An ethnography of forced migrants’ visions and plans for the future of creative work offers insight into how we might learn, adapt, and grow roots of resilience amidst periods of unpredictable change.

METHODS

The contents of this paper are based on original ethnographic data collected between January and April 2022 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. This research was conducted in partnership with Makers Unite, a Dutch social enterprise that formerly ran the Makers Unite Creative Lab (MUCL), a six-week professional development course aimed at self-identifying “creative newcomers”. “Newcomers” is intended to be an all-encompassing term used in the Netherlands to capture migrants such as asylum-seekers, refugees, expatriates, or immigrants. By being self-identifying “creatives”, research participants either obtained previous work experience in a creative industry prior to seeking asylum in the Netherlands, were developing a portfolio in a desirable creative field, and/or demonstrated aspirations to work in the Dutch creative industries. Interlocutors were primarily past MUCL participants, or “alumni”, whom I contacted directly to receive informed consent for their research participation with the assistance of Makers Unite staff. I met many interlocutors online for semi-structured Zoom interviews, which, for some, eventually turned into recurring, unstructured, and casual in-person meetings.

I would connect with my interlocutors primarily via WhatsApp or Instagram before meeting them in-person, again either at their home or accommodation. My analysis heavily explores the discussion and observations made during these in-person meetings; however, Instagram allowed me to keep casual weekly tabs on the whereabouts of my interlocutors and respond to their Instagram stories in real time to get to know them outside of a formal interview setting. Online social media served as an appealing platform to connect with interlocutors because I could witness their daily lives, observe creative practices exhibited online, and access otherwise unobtainable visual content.

In total, I interviewed sixteen research participants and engaged with several more MUCL participants in a casual nature through the Makers Unite Mighty Networks online platform, in-person community events, or during my participant-observation of the 20th iteration of the MUCL program – all of whom informed my findings. The two individual’s stories featured in this paper have been selected for their ethnographic and contextual richness and similarities in showcasing creative performance as a method of processual future-making. The themes presented in this paper are reflected in other examples emerging from this body of research, which are only unable to be included here due to length.

THE CAPACITY TO ASPIRE AND ‘ROOTS’ OF RESILIENCE

Conversations related to envisioning and conceptualizing ‘the future’ tend to lead into dialogues around hopes and aspirations. Renowned anthropologist Arjun Appadurai introduced the idea of a ‘capacity to aspire’ as a navigational, social, and collective capacity that captures the ability to engage with individual wishes and wants (Appadurai 2004; 2013, 188). By arguing that there is a need to examine how the poor or other marginalized groups seek to express their aspirations, Appadurai calls for the further development of an anthropology of the future (Appadurai 2013). In a former EPIC paper inspired by Appadurai’s writing, Mohanty and Saksena argued that the ‘capacity to aspire’ and ‘future-making’ are both culturally dependent and that to investigate and design for possible futures, ethnographers and designers must foreground emic perspectives in hopes of drawing attention to the ‘cultural map of aspirations’ of their research participants (Appadurai 2004, 59-84, cited in Mohanty & Saksena 2021). This paper continues to build upon Appadurai’s ‘capacity to aspire’ but centres his application of Hirschman’s theory of “voice” (1970), which calls for greater opportunities for the poor – along with other marginalized groups – to debate, contest, and oppose as a method of democratic participation in the design of new social systems in established society (Appadurai 2013). This opens a discussion ripe for further commentary on how the ‘capacity to aspire’ is practically observed (and strengthened) among a vulnerable population to access dialogues entrenched in various conceptualizations of the future. As ethnographers, how do we listen to the “voice” of historically marginalized groups to understand not just the aspects where change is sought, but areas where (underrepresented) internalized desires can take root to flourish and grow? In this research context, Hirschman’s concept of “voice” is operationalized and observed among research participants as vocalizations via oral communication, body language, and written texts (Hirschman 1970, in Appadurai 2013).

Over the past decade, creativity and art-based practices have been linked to the migratory experiences of refugees to foreground themes of political status, recognition, and belonging (see Rotas 2004; Hajdukowsk-Ahmed 2012; McRobbie 2016; Damery & Mescoli 2019). In hopes of building off of this literature further, I present a case that refugees in the Netherlands use opportunities of creative expression to build individual and collective resilience through theatrical performance and art exhibition. Refugees are observed to exercise their ‘capacity to aspire’ in the Netherlands by utilizing both new and familiar forms of creative self-expression as a means of experimenting – or rather playing – with imagined alternative future scenarios and their own vocational identities. By engaging with live performance in local drama troupes and theatre companies, these refugees involved:

Seek to strengthen their voices as a cultural capacity, [where] they will need to find those levers of metaphor, rhetoric, organization, and public performance that will work best in their cultural worlds. And when they do…they change the terms of recognition, indeed the cultural framework itself. (Appadurai 2013, 187)

As Appadurai explains, the ‘capacity to aspire’ has much to do with finding a localized method to negotiate the ‘terms of recognition’ that are applied to their social status. Refugees in the Dutch context demonstrate a willingness to engage with performance that will grab the attention of public audiences to debate and contest their (lower) status as perceived unwanted migrants seeking legal permits to permanently reside within the Netherlands.

By approaching this research from a bottom-up perspective of refugees, I intentionally reframe and centre uncertainty as a departure point to imagine and intervene with other possible futures. This is inspired by the work of Akama, Pink and Sumartojo (2018) who explore uncertainty as a process of disruption that enables new foundational knowledge to be gleaned from future-making possibilities. Therefore, uncertainty is not seen as a by-product or symptom of dealing with precarious circumstances. Instead, it is repositioned as a starting point to accept and normalize the very fact that immediate expectations for near and distant futures and anticipatory events are and will proceed to be subject to change.

If aspirations involve a change of state, linking resilience to change challenges its connection to a pursuit of resistance. I borrow Pink and Seale’s (2017) description of resilience, originally applied to the analysis of the Slow City movement in Australia. According to Pink and Seale, “we can understand being resilient as part of a process of weaving one’s way through the world, and thus as pertaining to alternative ways of living that are adaptive and relational rather than resistant to others” (2017, 191). In this manner, resilience is shown to be a future-oriented mindset, adopted in and for scenarios where the objective is to generate change. Thus, I argue that refugees engaging with creative practices are ‘growing roots’ as a form of resilience in their new environment. Resiliency is viewed not as resistance towards a confronting barrier, but as a form of exploration to grow “roots” (Pink & Seale 2017) and continue processes, or act on desires, that are already in existence. This method of resiliency affirms the belief that creative pursuits and aspirations need not end in the face of being forcibly relocated. Rather, like a plant being re-potted into new soil, refugees’ creative practices can take hold in new environment, a new country, and delve into new digressions linked to the future.

FINDING ONE’S VOICE

Next, I present two ethnographic examples of refugees living in Amsterdam involved in creative performance engagements. These examples are drawn from a group of refugees loosely connected to each other by association with Makers Unite, and their past participation in the Makers Unite Creative Lab. Both refugees were involved with two distinct creative production companies in Amsterdam. Note that names have been changed to protect the privacy and safety of the research participants.

Rehearsing alternative futures: Alek

I met Alek at the closing “Pitch Night” event of MUCL 18 in October 2021 when participants are recognized as graduates and welcomed into the MUCL alumni community. As we sat down during the program intermission to eat and chat, Alek told me that he dropped out of the program because he was too busy volunteering and rehearsing for the play that he was in. After moving from Russia and relocating a couple of times, Alek came to the Netherlands in 2019 to live safely with his boyfriend in a country where they could easily marry. He had worked as a fashion designer in Russia, then a fashion design teacher in China and the Philippines, and now Alek found himself working in an Italian home furnishing retail show room as the store manager. Albeit a change from his well-established professional experience in the fashion world, Alek was happy to have a stable and steady job as he dabbled with new experiences while setting up his life in Amsterdam.

Between January and March 2022, I met Alek on and off at the store where we would share a coffee and sit among the stylish home décor as if it were a proper living room to lounge. Alek and I easily discussed the reasons for wanting to get out of the fashion industry: him citing poor mental health, environmental degradation, and sustainability as driving factors. Above all, he maintained an attitude of wanting to try everything – particularly new hobbies that might lead to a career change. He joined a theatre group specifically seeking refugees to be part of the cast ensemble. Alek was one of the many refugees cast in the ensemble of Wat We Doen’s performance of “Hoe Ik Talent Voor Het Leven”, a Dutch stage play based on the eponymous novel by Iraqi author Rodaan Al Galidi. The play tells the story of an asylum-seeker who lived for nine years in a Dutch asylum-seeking camp (in Dutch known as an “AZC”). Alek joined the cast in fall 2021 when the theatre production was resuming after months on pause due to the coronavirus pandemic. He admitted that working at the store was enough for now, but the theatre production had “injected him” and now he was addicted. He adored it all: the exposure, the spotlight, the feeling of freedom on stage. Even though he was an unnamed character up until the very end of the play. Even though he was a member of the ensemble cast that mostly operated as a singular fluid body. On stage, he transformed into a different version of himself.

Figure 1. Stage of Wat We Doen’s performance of “Hoe Ik Talent Voor Het Leven” at Stadsschouwburg Utrecht (Municipal Theatre Utrecht) on 18 March 2022. Photograph by author.

I attended the play in mid-March with a friend to witness Alek perform live. What became clear to me during the production was the way that the performance simultaneously explored and exploited the emotions in the original timespace of living in an AZC on stage to access visions of a redesigned asylum-seeking process. The play’s plot confronts the audience with the presumed realities of the dehumanizing hardships and challenges that asylum-seekers face in the Netherlands. Characters legal residence papers are denied, a child born in the AZC celebrates multiple birthdays to signal the passage of time, racist and xenophobic remarks are made by fictitious Dutch government workers. Although the performance was by no means improvised and the actors were following a pre-destined script, the nature of each performance was that no two nights were ever the same. During a meeting, Alek described the experience being particularly emotional due to the nature of rehearsing, and therefore reliving, parts of his trauma:

Of course, our emotions is [sic] important. What we’re doing on stage. The concentration – it’s everything. And you – you’re reliving it together, again, and again. This is also… Because before you don’t understand how the actor can cry, again and again, on the same thing. But it’s possible… Every time it’s different. Because it very depends on the group. (Field notes)

The act of rehearsing and performing multiple times suggested that Alek, along with his fellow castmates, were in a mode of constant tweaking and practice with the intention of performing in a certain way in the future. I argue that rehearsal divides this creative engagement into a series of steps, where each practice is part of the journey, or process, of preparing for the play. Being part of the play is processual. One cannot jump to the final show without rehearsing the movements, actions, hand gestures, dance sequences, even if certain segments will be improvised in the moment.

Despite the intense emotion delivered with each performance, in our chats together, Alek described how enjoyable this experience was for him. He embodied, really taking to heart, the uncertainty that comes with his migratory experience to empower himself to continue discovering what he wants to do in terms of work and where he wants to spend his energy. While critics might claim that it was chance that Alek found a production troupe looking for refugees to provide a genuine and authentic experience to the play’s topical subject matter, Alek persisted that this valuable opportunity opened up a new avenue for him to explore a vocational aspiration as an actor. Alek affirmed that this performance group allowed him to try a new creative practice and strengthen his bonds with the refugee community in the Netherlands. He was inspired by being on stage and the attention he has received from performing. He was even featured in the media as a ‘poster boy’ for what the refugee experience “could” be like.

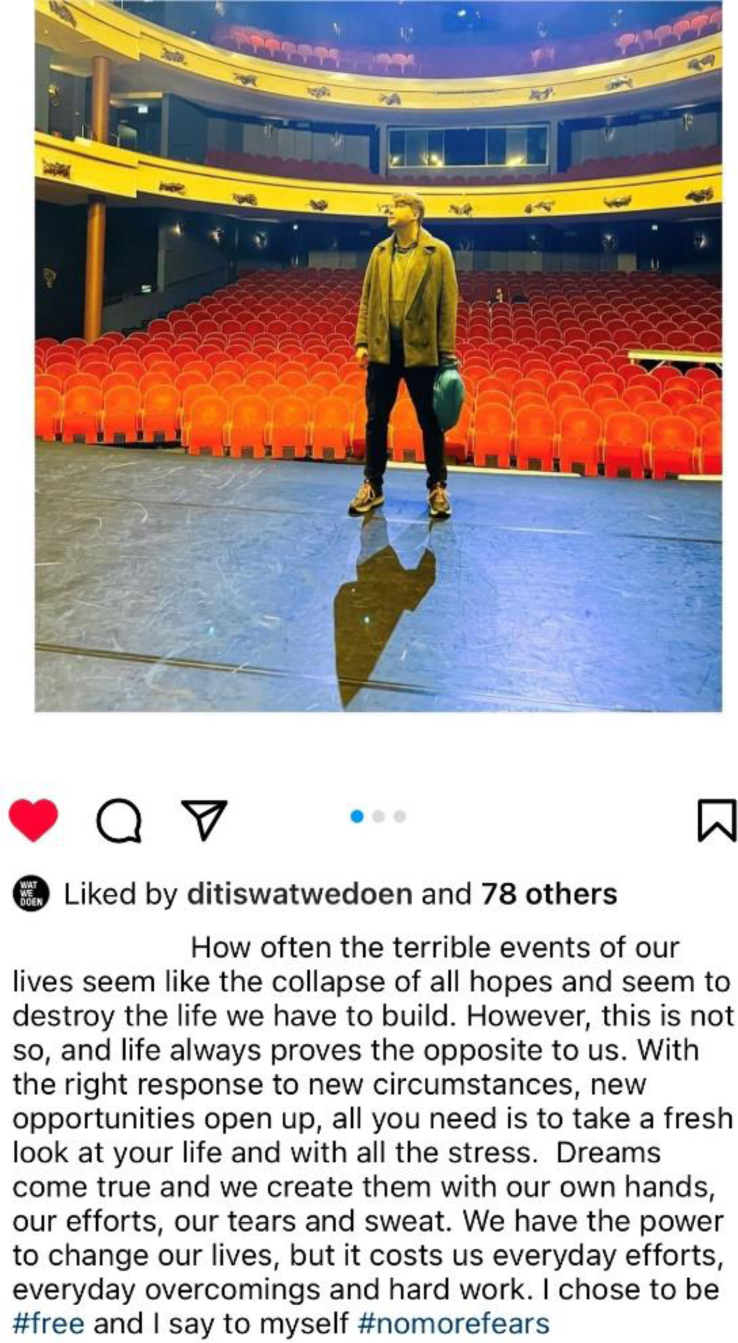

Alek posted this photograph on his Instagram page after one of his performances. Part of his caption reads “dreams come true and we create them with our own hands, our efforts, our tears and sweat” (Instagram post, February 1, 2022). Alek acknowledges his own involvement in ‘future-making’: temporarily practicing what it would be like to explore a career as an actor, and the ideal imaginaries of a redesigned asylum-seeking process. To quote Morten Nielsen, for Alek his involvement with the play illustrated the ways that “the future exists as an unstable transformative potentiality” (Nielsen 2014: 17). The caption also emphasizes Alek’s own agency and self-accountability he sees in this transformative process of being involved in the play. By saying “we have the power to change our lives, but it costs us everyday efforts, everyday overcomings and hardwork”, Alek acknowledges that he is a future-maker, actively participating in the rehearsals of his future career.

Figure 2. Screenshot of Alek’s Instagram post shows him standing on stage during the production run of “Hoe Ik Talent Voor Het Leven”. Photo taken by unknown. Caption written by Alek. Both used with permission.

Writing unknowable futures: Kaif

Originally from Kuwait, Kaif is a member of the LGBTQIA2+ community. We met at a community-organized clothes swap hosted at the Makers Unite studio. Within a matter of minutes of talking, Kaif sprung to show me his Instagram account where he published some of his poems and written musings. For him, creative expression takes the form of writing, whether it is through poetry and monologues; performing stories that explore his repressed sexuality and dabble with alternative realities and unknowable futures. It allows him to express his thoughts and experiment with new ideas that he would have had to hide away out of fear of persecution as a gay man, prior to seeking asylum. After several meetings and walks together, he shared with me a story he was working on from the perspective of a straight married woman who wants to test her ego by asking her husband to sleep with a sex worker. His writing allows him to share and tell stories of his own sexuality that he has never expressed publicly before and imagine possible futures in this perceived sexually liberated country of the Netherlands.

Kaif often came back to philosophical and stereotypically “heavy” topics in our lengthy walks around Amsterdam’s Centrum area. I often felt like he was hungry to explore topics that perhaps he did not have a chance to engage with in his youth while still residing in Kuwait. Once on a walk, he explained his writing process and inspiration for his most recent monologue about the Dam Square monument performed during a collaboration with a local production company that habitually engages with international performers. Kaif explains:

And then, the last part was the monologue that I read about ‘we’ in the future. Because then, that part I am talking about Amsterdam drowning, but because of climate change. Like, I imagine that I am the only one swimming there. And I can just pull the tip of it, and everyone is just floating around me…At the end of the monologue, I saw that I, I am angry or I’m mad about the people who used to look at the Dam Square from below. Which is now, like me and you, [we] are looking at the Dam Square from below because the drownings have not happened yet. So, in this sense, I was talking about the future. (Field notes)

Figure 3. Panorama of Amsterdam’s Dam Square and pedestrians walking by on the street. The Dam Monument is seen in the background. Photo taken by author.

Kaif prepared and performed a monologue about what the famous Dam Square monument might look like in 300 years for a one-weekend play. His vision of the future is grim as he wrestled with the effects climate change, rising sea levels, population growth, and lack of human intervention might cause.

Kaif rehearsed his monologue over and over multiple times. Despite the repetitive nature of rehearsals – similar to Alek’s stage play – no two takes were the same and Kaif was re-energized to express the same words with new conviction and emotion. Each time, he resuscitated a call for help, sharing his desperation that climate change will flood our cities and leave our ancestors wondering what happened. Unlike Alek’s performance though, Kaif depicted a future much further ahead in time, a century when he most certainly would not be alive to witness. In this way, his monologue explored how “people engage in potential futures that they know will never follow the present, and through the recognition of impossibility the future invades the present and itself is liberated. That which will never be is already there” (Bryant & Knight 2019, 129). For Kaif, the “that which will never be” refers to his own presence at the Dam Square’s monument in the 200 to 300 years when he imagines this flooding to occur and when his monologue is set. He is projecting out into the future hundreds of years from now to say that if we (the collective ‘we’) do not act against the imminent climate crisis, we can likely expect sea levels to rise and the most recognizable pieces of our city will be distorted, submerged, and effectively gone. Therefore, Kaif writes about an unknowable future. He says:

But my dream then is now, as though it’s happening now. So, I just wanted that chance to, like, look at…try to change, to try and avoid what would have happened. But in this monologue, I’m already drowned and I’m already touching the tip of the monument. (Field notes)

This is yet another example of how creative newcomers like Kaif find ways to write and rehearse their own creative practices as a method to engage with unknown futures. The poetic rhetoric of Kaif’s monologue is bleak and somber, especially since he intended for it to be a warning for audiences listening today. However, a warning can be interpreted as a statement of something that may – hopefully – never be a reality. Bryant and Knight explore this idea that, when practitioners think about the future, there is an admission that a potentiality may also never come to pass (2019, 108). Of course, Kaif’s monologue is a piece of fiction, a poetic narrative that paints the Dam Square completely submerged underwater. However, it allows him to delve into a future, seeing it as a potential experience he does not wish to see come to fruition.

CREATIVE PERFORMANCE AS RESILIENCE

Alek and Kaif’s stories show that creative self-expression can be a pathway to imagining new futures. They demonstrate how creative performance is future-oriented on a topical level: looking towards either near or distant futures and the potentialities that exist with or without further human intervention. For Alek, he is focused on an eminent future: a version of the future where refugees are treated with greater dignity in the asylum-seeking camps where temporary shelter is found. For Kaif, he imagines a more distant, and yet still imminent, speculative version of the future; where the effects of climate change have become so severe that sea levels have risen to the point that the famous Dam Square monument has drowned. Resilience in these performances reveals itself through the acceptance and admission to explore alternative situations. As a term, ‘resiliency’ captures the creative mindset that exists to speculate about the future and describes a method of experimentation with said futures. In doing so, Alek and Kaif’s stories showcase the connection between forging new lives and navigating uncertain futures. As humans, I believe we are constantly looking for ways to adapt and evolve in new environments.

Often, normative views of resilience entail bestowing the concept in the present in reference to past events. Many a times, it is after a perceived obstacle has been overcome or a challenge has been faced that resilience is attributed to those involved. Yet, these ethnographic examples suggest resiliency possesses a future-orientation and can hinge on other temporal orientations. Both performers prepared for their respective upcoming performance with anticipation, showing how creative performance is future-oriented in that it requires preparation and rehearsal. Bryant and Knight posit that anticipation is a temporal orientation that allows us to conceptually pull the future towards us through executing actions in the present time space (Bryant & Knight 2019).

At the same time, rehearsal and practice are elements composing the process of imagining futures – a form of creatively cultivating resilience. In individual and collective ways, research participants were engaged with rehearsing a version of the future: practicing the performance; aiming to adjust and refine the level of emotion, intonation, hand gestures and bodily movements they wish to express at the time of (future) performance. This reflected a type of future-making exercise that Joachim Halse utilized in his case study where users were asked to improvise and perform, first with dolls then with acting out themselves, how they would engage a new waste management system at their work location (Halse 2013). Therefore, Kaif and Alek here too demonstrate a degree of “corporeal materiality” where the body itself becomes the materials involved in a type of future-making. Future-making has often been defined by giving tangible form to abstract imaginings or visions of the future (Halse 2013). In this scenario, if we think of performers’ respective bodies as the materials, they are engaged with a method of “future-doing”.

As a process that is rehearsed, tweaked, and then vocalized, performance is an accessible opportunity to “voice” aspirations (Hirschman 1970, in Appadurai 2013). In addition to the future being a mere subject matter topic for theatrical performance, both performers flex their vocational aspirations as creatives within the Netherlands: Alek experiments with a new vocational identity as an actor, while Kaif reinforces a professional identity as a creative writer. Thus, creative performance becomes an outlet and opportunity to find an accessible way to “voice” their aspirational vocational identities (Hirschman 1970, in Appadurai 2013).

Having been forced to relocate to a new country out of fear of persecution and violence, for Kaif, the process of integration is not far removed from a process of reinvention. While he previously had an unsatisfying career as a HR administrator at a major Syrian bank, Kaif experiments with his writing, seeking opportunities for publication and performance, while also enrolling in a social work degree to keep options open. I do not share this example to emphasize the individualism of Kaif’s experience. I recognize that much literature on the topic of resilience connected to refugees seeks to draw attention to the role of community and credit “the contextual and social factors that support individual resilience” (Balfour et al. 2015, 18). This pair of refugees shows a need to express and vocalize their experience, demonstrating a method of also participating in democracy to highlight what a desirable future might look like for them and for the collective community.

By getting involved in each of these stage performances, both Kaif and Alek are exercising their “voice” (Hirschman 1970 cited in Appadurai 2013, 183-6) in a literal and both metaphorical way of representing themselves, gaining audible strength, and conviction with each performance. Appadurai insists:

Voice is vital to any engagement with the poor (and thus with poverty), since one of their gravest lacks is the lack of resources with which to give “voice,” [Hirschman 1970] that is, to express their views and get results directed at their own welfare in the political debates that surround wealth and welfare in all societies. (Appadurai 2013, 183)

To start with Alek, through his involvement in the play, he is exercising his metaphorical, creative “voice” to express his views and desired results to change the treatment of refugees in asylum-seekers’ camps. In this way he is maximizing an opportunity to engage with an audience to express his metaphorical “voice”. For Kaif, his writings and monologue engage with already unknowable futures to accept and speculate what might occur if our collective actions do not change.

Coupled with the excitement of trying something new, theatre becomes a participatory act of democracy, where performers are voting for what an alternative future might look like for them and the collective. Public performance is used as an explicit example by Appadurai that can captivate audiences to seek future change. Similarly, Damery and Mescoli connect the arts to political engagement, stating:

In spite of structural constraints, art is a means (and a product) through which migrants, independent from their legal status, participate in the local socio-cultural life and elaborate concrete claims concerning their own situation as well as global concerns that are related to it—such as migration governance and politics. Art practice constitutes a creative political engagement in the local context (Salzbrunn 2014) and also a way for people to find belonging without caveats (Martiniello 2018). (Damery & Mescoli 2019, 14)

Investigating resilience can be mistaken as an opportunity to investigate the empowerment of audiences to withstand social change or overcome adversity, fundamentally overlooking the possibility to see resilience as a way of evolving to inspire more change that allows for certain aspects to flourish.

Yet, citizenship also influences the boundaries by which we perceive and interpret artistic intervention as well. Cultural theorist Nancy Adajania uses the concept of ‘performative citizenship’ to draw attention to this and explains it as a “crossover from symbolic to actual political action, and the production of a newly aware and self-critical community that can transcend the traditional boundaries of group identity” (Adajania 2015, 40). As ethnographers, this concept ushers our positionality and relationship to the subject matter at hand to the forefront, to (re)consider how our status impacts the lens by which we see performance. For example, Alek is among forty cast members comprising the ensemble, excluding the actors, musicians and past ensemble members who had to drop out of the play when coronavirus hit. Their rehearsals and interaction with the play is seen as an act of ‘performative citizenship’, by bringing awareness to the treatment of asylum-seekers and forming a new group identity as a cast ensemble. Ironically, the play is in fact on the topic of refugees – a controversial matter related to the very nature of citizenship itself. Ariella Azoulay draws on her expertise following Islamic and Palestinian projects to discuss the citizenry boundaries of the body politic in re-affirming nation-state identity. Azoulay proposes:

In the same vein, citizenship in differential political contexts cannot be understood just as an optional theme for political discussion and artistic intervention. Citizenship is what defines the relationship between the protagonists involved in the production and consumption of art—i.e., artists and spectators alike—and what is reproduced through it. (Azoulay 2015, 70-71)

As ethnographers, it is equally importantly to consider the positional lens we adopt in understanding artistic interventions and the production of creative performance. To see creative performance as a method of resilience means allowing for the aspirations expressed through the creative practices in question to stem from experimentation; and recognition of such vocalizations occurring against the backdrop of uncertainty and despite anticipated change. I note that similar lessons can be drawn from the practice of design fiction, as ways of engaging with fictitious future scenarios, to aid speculations and spur political action (see Gonzatto et al. 2013; Salazar et al. 2017).

PROCESSES OF RESILIENCE VERSUS SYSTEMS OF ASSIMILATION

Seeking out resistance or resiliency was not initialling one of the main goals of this ethnographic research. As a researcher, I set out to understand how refugees engaged with temporal orientations towards the future and pursued their vocational aspirations. But discussions around aspirations undoubtedly involved observations around how do refugees enact their vocational aspirations.

In The Future As Cultural Fact, Appadurai warns against the ‘ethics of probability’: ways of thinking, feeling, and acting that depend on statistical and probabilities tied to the growth of capitalism, profits from catastrophe or disaster (Appadurai 2013, 295). Appadurai argues in favour of the need to nurture their ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013). The fluid uncertainty that refugees face in the Netherlands and lack of economic resources, irrefutably places them in a vulnerable position more susceptible to these ethics of probability. When viewing resilience as a processual form, the ‘capacity to aspire’ which may be considered weakened during their migratory experience, can be reframed as something potentially neither lost nor stolen but tucked away during the migratory experience.

Thus, resiliency is shown as a slow process that takes time to nurture and grow. It is rehearsed and practiced repeatedly, reinforced, and strengthened like a monologue committed to memory. However, there are systems of assimilation at play in the Netherlands that apply pressure on those to adapt and learn that suits rather not their creative pursuits or vocational aspirations, but what works for the existing system already. Resilience can be collective and individual and, as these examples have shown, engaging audiences to react and inspire action to change future outcomes, challenging existing systems of assimilation, and allowing for the vocalization of creative self-expression to experiment with different futures. As ethnographers, we must look at what may or could be changed (as a reactive process), but also what we want to stay the same and keep constant within our lives. Where are the opportunities to grow “roots” (Pink & Seale 2017) that keep us planted in new ground that is fertile for experimentation? Broadly speaking, where do our interlocutors seek consistency, opportunities to act and enact their desired future? How are those opportunities for consistency in contrast for the experimentation that sprouts a desire for change too?

Finally, I return to arguments made by Panthea Lee, who observed and condemned how many ethnographers and researchers – herself included – are often complicit in assisting large companies and government bodies (organizations that are rich in resources and able to assert power and authority) to imagine future scenarios that benefit their interests. She asserts:

When these folks [those who work for companies and governments] are asking what the future should look like, we get the version of reality that we’re living in now. And I think we need to bring folks that have radical imaginations, that bring moral clarity and courage, to ask those questions. (Lee 2021)

Building upon the writings of anthropologist Anand Pandian, Lee goes to argue that it is our responsibility as ethnographers to listen to the radical imaginations of artists as social actors to write ethnographies that possesses moral clarity (Pandian 2019, cited in Lee 2021). I believe this type of moral clarity is meant to suggest a type of innocence that is untampered by the ‘ethics of probability’ that Appadurai is referring to: ideals and values that remain when not tied to the growth of capitalistic ventures. In this way, my research contributes to the current discourse tied to anthropology of the future and the benefits of future-oriented ethnographic studies from a bottom-up approach. By critically examining how refugees engage with creative performance, I encourage the EPIC community to reconsider how resiliency is often projected onto vulnerable populations and caught up on exclusionary dialogues of empowerment. Idolizing displaced groups can overlook how researchers think about rebounding as a process, but really thinking more critically about the benefits from reimagining (letting go of former expectations) to then speculate new scenarios. Instead, a bottoms-up approach has allowed commentary on how forced migrants exercise their own ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013) and search, and/or negotiate, for terms of recognition in their daily lives while seeking employment opportunities. Anthropological future studies can benefit from the contribution of even more ethnographic fieldwork that adopts an approach of resilience as a mindset to engaging with creative practices.

CONCLUSION

From the perspective of refugees in the Netherlands, resiliency is shown to be future-oriented and processual through creative experimentation and exploration. Once granted legal status, asylum-seekers and refugees in the Netherlands facing drastic degrees of uncertainty towards their future experiment with new aspirations while integrating into the Dutch economy. Refugees bring to life Appadurai’s ‘capacity to aspire’ through the processual steps involved in creative performance and the activation of their “voice” (Hirschman 1970, in Appadurai 2013). Despite going through what can be extreme mental health concerns, requiring intense therapy to deal with trauma, depression, anxiety and/or PTSD, there are accounts of people finding new forms of creative self-expression to experiment and play with new imagined futures. The anticipation and hope of multiple possible futures or alternative ways of living encourages ethnographers to acknowledge how vulnerable populations are inspired to dream and, by doing so, preserve and maintain a ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013).

By centering present creative practices and future uncertainty, this paper unpacks how we can advance the value of ethnography by learning to clue into hidden narratives of creative resilience among forcibly displaced migrants. I suggest that through the observation of creative arts-based practices, new narratives can emerge (which may be called a form of ‘design fiction’). Resiliency is not simply about adapting to a new life, but about pushing the boundaries of aspiration and experimenting with previously inaccessible or unimaginable futures due to circumstance. To borrow the words of fellow design anthropologist Thomas Binder, “Prototyping is not only a generative process of ideation. It is just as much a rehearsal of new practices” (Halse et al 2010, 180). “Prototyping” may very likely be a much more relevant and commonly heard term among the community of research practitioners connected to the EPIC. As we work alongside vast teams of strategists, designers, and engineers, I encourage practitioners to toil with how we leverage generative arts-based practices to engage with alternative futures. Where do we see the benefit of more processual steps that prepare us for the future and allow us to ‘grow roots’ that stabilize us in our practice and, perhaps more importantly, ground us in a common vision of the future?

Most of this paper is directed to employing resilience as a creative mindset which invokes further applications to methodology and how we engage with research participants in understanding their dreams and aspirations for the future. However, given the global influx of refugees as an issue of today, this paper also raises a question to ethnographers, how can we adjust our participation in systems that work beyond ‘integrating’ vulnerable populations by providing them with resources to voice their (creative) imaginations? While participatory arts programmes for those with refugee backgrounds have achieved greater public recognition and documentation in recent years (Balfour et al 2015), it would be a disservice to say that the insights from this paper are only applicable to forced migrants or new arrivals. How do we refrain from oversimplification, while honouring the agency and variety of stories of those most marginalized in society? I hope to facilitate discussion on ways that art and work can be combined that does not simply resist assimilation but participate alongside those pressures. I urge practitioners to adopt a mindset where resiliency is grounded in pursuit of aspirations, challenging a belief that adaptation, learning, and evolution sprout in defense of unwanted disruption.

Nicole Aleong (she/her) is a design anthropologist passionate about the intersection of futures thinking, innovative technology, systems design, and decoloniality. Originally from Vancouver, Canada she has several years of experience working as a strategic research consultant and professional moderator. She holds a MSc in Cultural and Social Anthropology, specializing in applied anthropology, from the University of Amsterdam and a BA in Anthropology from the University of British Columbia. www.nicolealeong.ca.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – Thank you to Dr. Jamie Sherman, Dr. Adam Gamwell, and Hilja Aunela for their encouragement and contribution to the development of this paper. Thank you to Makers Unite for allowing access to your community of newcomers and your partnership in support of this ethnographic research. Last and most importantly, thank you to the community of refugees and asylum-seekers that shared their stories and in doing so strengthened their own capacity to aspire. To you, I am extremely grateful.

1. EPIC2022 Website. Accessed 15 August 2022. https://2022.epicpeople.org/theme/

REFRENCES CITED

Adajania, Nancy. 2015. “The Thirteenth Place and the Eleventh Question: The Artist-Citizen and Her Strategies of Devolution.” In Future Publics (The Rest Can and Should Be Done by the People: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art edited by Maria Hlavajova and Ranjit Hoskote, 28-61. Utrecht: BAK.

Akama, Yoko, and Sarah Pink, and Shanti Sumartojo. 2018. Uncertainty and Possibility. London: Bloomsbury. Kobo.

Alayarian, Aida. 2007. Resilience, Suffering and Creativity: The Work of the Refugee Therapy Centre. London: Routledge. eBook.

Appadurai, Arjun. 2013. The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. London: Verso.

Appadurai, Arjun. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition”, Culture and Public Action (eds) V. Rao & M. Walton, 59-84.

Azoulay, Ariella. 2015. “Nationless State: A Series of Case Studies.” In Future Publics (The Rest Can and Should Be Done by the People: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art edited by Maria Hlavajova and Ranjit Hoskote, 62-89. Utrecht: BAK.

Balfour, Michael, Penny Bundy, Bruce Burton, Julie Dunn, and Nina Woodrow. 2015. Applied Theatre: Resettlement, Drama, Refugees and Resilience. London: Bloomsbury.

Bryant, Rebecca, and Daniel M. Knight. 2019. The Anthropology of the Future. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Damery, Shannon, and Elsa Mescoli. 2019. “Harnessing Visibility and Invisibility through Arts Practices: Ethnographic Case Studies with Migrant Performers in Belgium.” Arts 8, no. 2:49. DOI:10.3390/arts8020049.

Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese, Frederick M. C. van Amstel, Luiz Ernesto Merkle, and Timo Hartmann. 2013. “The Ideology of the Future in Design Fictions.” Digital creativity (Exeter) 24, no. 1: 36–45.

Hajdukowski-Ahmed, Maroussia. 2012. “Creativity as a Form of Resilience in Forced Migration.” In Coutnering Displacements: The Creativity and Resilience of Indigenous and Refugee-ed Peoples, edited by Daniel Coleman, 205-235. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press.

Halse, Joachim, Eva Brandt, Brendon Clark and Thomas Binder. 2010. Rehearsing The Future. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Danish Design School Press.

Halse, Joachim. 2013. “Ethnographies of the Possible.” In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice, edited by Wendy Gunn, Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, 180-196. London: Bloomsbury.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Response to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lee, Panthea. 2021. “Exiting the Road to Hell: How We Reclaim Agency & Responsibility in Our Fights for Justice”, Keynote presentation October 19, 2021, EPIC 2021 Conference. https://www.epicpeople.org/exiting-the-road-to-hell/

McRobbie, Angela. 2016. Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Mohanty, Abhishek, and Gitika Saksena. 2021. “Reimagining livelihoods: An ethnographic inquiry into anticipation, agency, and reflexivity as India’s impact ecosystem responds to post-pandemic rebuilding.” EPIC Proceedings: 174-200, ISSN 1559-8918. https://www.epicpeople.org/reimagining-livelihoods-impact-ecosystem/

Nielsen, M. 2014. “A Wedge of Time: Futures in the Present and Presents without Futures in Maputo, Mozambique.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 20, no. S1:166-182.

Pandian, Anand. A Possible Anthropology: Methods for Uneasy Times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478004370

Pink, Sarah, and Kirsten Seale. 2017. “Imagining and Making Alternative Futures: Slow Cities as Sites for Anticipation and Trust” In Another Economy Is Possible: Culture and Economy in a Time of Crisis edited by Manuel Castells, 187-203. Malden, MA: Polity.

Rotas, Alex. 2004. “Is ‘Refugee Art’ Possible?” Third Text 18, no. 1: 51-60.

Salazar, Juan Francisco and Sarah Pink, and Andrew Irving, and Johannes Sjöberg. 2017. Anthropologies and Futures: Researching Emerging and Uncertain Worlds. London: Bloomsbury.

Van Tubergen, F. 2006. Immigrant Integration: A Cross-National Study. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC.