Marietta is 61 years old. She takes care of her adult son (unemployed) and her daughter-in-law (disabled), both of whom live with her in a simple 3-bedroom house on the wrong side of the freeway. Her rent is sky-high, because in Silicon Valley rents are crazy on both sides of the freeway. Marietta also contributes to her mother’s care. She is trying to keep up payments and insurance on three cars, one of which is currently non-operational, and she has title loans on the other two. And she has a set of payday loans outstanding.

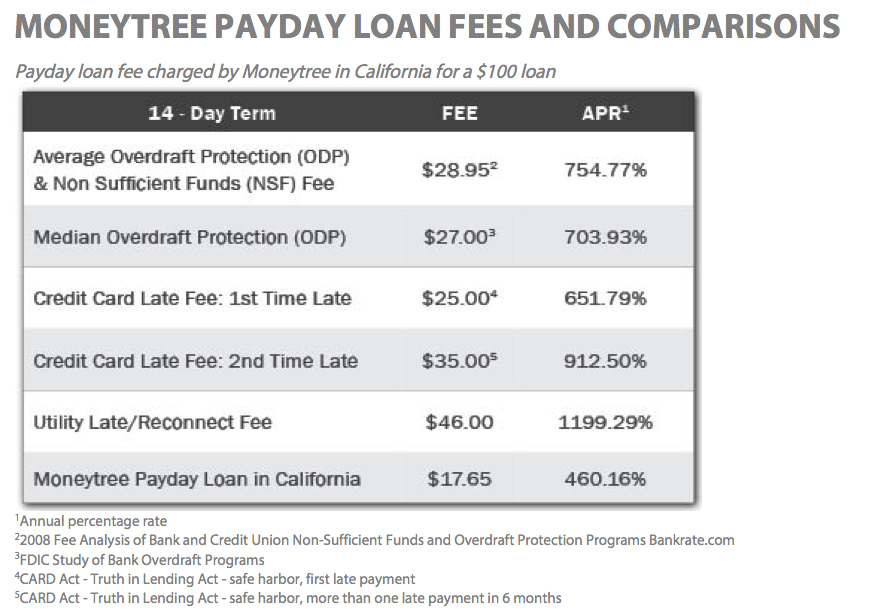

Small-dollar subprime loans like the ones Marietta has are marketed only to those who have few choices. Payday loans are meant to tide you over until your next paycheck, so they run at most for a period of two weeks. In California, you can borrow up to $300, but a fee of $45 is immediately withheld, so you end up with $255 in hand. You owe the full $300 in two weeks or less. If you can’t pay it back in full, you “roll it over.” That is, you get a new loan: you pay $45 and the $255 from the new loan is used to make up the difference. And so on, ad infinitum. You pay $45 biweekly just to service your loan. The APR for this whole setup is about 460%. (APRs are even higher in many other states and for off-shored internet payday loans.) Here’s how MoneyTree, a payday loan provider, explains what a good deal it is to get a payday loan:

Title loans are typically made in larger amounts. In California, 99% of title loans are for more than $2500, since interest rates above that amount are unrestricted. A typical title loan in California has an APR somewhere between 75% and 100%. Nationwide, it is not unusual to see title loans with an APR of 300%. All this at a time when the wealthy get APRs around 4% on their loans.

Marietta had taken her first payday loan to pay an overdue bill, thinking that she would be able to repay it in full when she got her next paycheck. Unfortunately, she was overly optimistic. First she had to keep rolling over the loan. Then she didn’t have the additional $45 fee to roll it over. So she took a second payday loan through a different lender, to service the first one. Things snowballed from there.

To keep her household going, hold her family together, and service her debt, Marietta worked two jobs. She was a full-time patient manager at a local clinic. She had a second job as a receptionist at a health club. She worked about 70 hours in a typical week. She participated in research studies for the incentives. In addition, she worked catering jobs whenever she could get them. She rented out two bedrooms in her house, including her own, forcing her to sleep on the couch.

Sad to say, the only fictional element in Marietta’s story is her name, which has been changed to protect her privacy. It was real-life stories like hers that originally called the collective FAIR Money into being. Formed in 2012, the group is united by the conviction that financial services such as these are exploitative, unfair, and incompatible with the fundamental political principles on which the US is built. We wanted to do something about it.

Most of us have a background in anthropology and/or design research. We opted to stay self-funded, resisting the lure of ample grant money available for financial literacy projects, as it would have forced us into a set of assumptions and a specific construction of the problem at hand that we were not ready to commit ourselves to. We started with a research project designed to build an understanding of what kind of assistance would truly help low-income people who find themselves in a cash crunch. At least some of us also nursed a very general hypothesis that you could possibly force more reasonable rates and fees by offering financial services at cost, undercutting predatory lenders.

We recruited on Craigslist, starting with a questionnaire that allowed us to select participants who had taken payday loans or were otherwise struggling with debt. We also chose them to represent a range of ages, incomes, and ethnic identities. We visited participants to conduct an initial interview about their current financial situation. They then did a month-long financial diary, documenting their financial actions and decisions. They ended with a final interview about financial strategies, in which they also drew a financial sociograph.

As is usually the case when doing research, we found many things we didn’t expect. To list just a few insights, we learned a lot about how family roles and obligations structure and complicate financial decisions, introducing unquantifiable values into what might otherwise seem simple calculations. We observed, though from some distance, the process people go through when their household economy contracts and how they apply short-term solutions to what they hope and pray are short-term problems, but which—at this particular point in history—often turn out to be long-term realities. We saw how creative people get and how hard they work when their income flatlines while the economy around them takes off like a rocket. And, most salient of our findings, we learned that people are really good with money, stereotypes notwithstanding.

Attending to typical political discussions and prescriptions, one might easily conclude that poor people need to be saved from themselves. They need to be trained. They need to be taught. They need to be forced out of a poverty they embrace, out of laziness, ignorance, or some other perversion of the classic American virtues of hard work and self-reliance. The “culture of poverty” literature concurs, suggesting that poor decision-making is fundamental to their plight and is passed from generation to generation.

Bringing an anthropological perspective to the decision-making of our participants painted a very different picture. Our participants aren’t lacking in intelligence, financial literacy, motivation, or work ethic. They have a high level of intricate expertise necessary for survival within a socioeconomic system stacked against them. On balance, our participants were overwhelmingly smart, skilled, determined, and disciplined—much more often than they were careless or reckless. True, they may not have read the fine print on their loan papers, and in that they are undoubtedly not alone. And also true, they tended to focus on the present, on getting through the month, without worrying a great deal about the future. If your future is bleak, it pays to be “happy-go-lucky,” as Marietta described herself.

Indeed, the skills and choices of our participants were eminently practical and highly relevant to their circumstances. For example, they all knew what utilities needed to get paid first, and which ones you can negotiate payment plans with. They explained a variety of shopping skills, to keep their food and clothing expenses to a minimum. They knew how best to minimize costs on financial transactions when you can’t afford a bank account. Their hardest task—and the skill least easily acquired—was knowing how to negotiate the labyrinthine government assistance programs and the vast array of private charities. Of course, this is not the skillset that a typical financial adviser has or that a financial literacy program would teach them, but it definitely helps many people make the best of a raw deal. (For more details, see our report “Good with Money”.)

As FAIR Money gained these insights into the financial expertise of people who struggle to get by, we also developed a better understanding of who is out there trying to make a difference, what types of potential solutions actually make sense, and where the gaps are in a crowded field of charities, responsible lending organizations, hackathons full of well-intentioned developers seeking salvation in apps, savings programs, social savings programs, lawyers lobbying for better regulations, sharing services, social entrepreneurs, and even some valiant efforts that try to unify and integrate the many and fractured aid programs that are available to people who fall on hard times.

We have come to understand that the biggest gap, the biggest hole in the vast tapestry of both predators and do-gooders, is in human-centered perspectives. There are many proffered solutions, but they are top-down, ideological, and inspired by outdated constructs that may have had some relevancy in a less unequal past, but that have nothing to do with the realities of people trying to make ends meet under conditions of exceptional inequality. While there is quantitative data that propels many to do something, what’s missing is the ethnographic insight that will anchor those solutions in concrete reality, in the actual lives lived by the intended beneficiaries.

Where FAIR Money once envisioned doing research in order to find a solution, we now believe that doing research, in very important ways, is the solution. Our next project aims to work with people dealing with financial stresses to build a knowledge base of financial skills and expertise that are truly helpful and relevant to their circumstances. We aim to invite them in as the experts on what works and what doesn’t. We will draw on our backgrounds in anthropology and corporate ethnography to create a space for people to tell their stories and to create a framework that will help them be more effectively heard.

We encourage anyone in this community to join us or to embark on their separate journey to bring their anthropological expertise to bear in public life. All of us bring a way of looking at experience, a way of understanding why and how things happen, a way of analyzing problems and putative solutions, that has the power to make a significant difference in an often cold-hearted, often misguided world.

References

MoneyTree Payday Loan Fees and Comparisons (image): https://www.moneytreeinc.com/loans/california/payday-loans, accessed July 3 2015.

0 Comments