Case Study—The authors used anthropology and other design research methods to develop a new kind of study to capture the world of professional creatives and the people they work with. To uncover core collaboration challenges for professional creatives the authors asked them to walk through past projects, who they interacted with at different points, and discuss their affective experiences.

Critical collaborative problems for participants in this study stemmed from two factors: ever-increasing corporate demands to do more with less, and concurrent attempts to automate feminized administrative coordination tasks. To communicate actionable findings, the authors balanced systems-level thinking with the identification of the kinds of problems Adobe could and would solve. While large scale social change was outside the scope of actionable recommendations for a product design team, the implications of social structures on individual experience provided insights that widened our lens beyond the individual.

What else does the history of ideas prove, than that intellectual production changes its character in proportion as material production is changed? (Marx 1848:25)

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, Adobe entered the world of software as a service by introducing Creative Cloud and transforming creative tools such as Photoshop and Illustrator from boxed to subscription. From the beginning, Adobe knew collaboration would be important for the success of a cloud offering. The initial release of Creative Cloud included features like shared file-storage and libraries functionality that attempted to make collaborative work easier for creatives. Users could now send their work through links that could be opened by anyone they wanted to share with— even those who previously lacked the Adobe software to open a design file. With a broadening of the range of people interacting with Adobe Creative Cloud, it was no longer enough to consider the solo creative user behind the screen. Instead, the company needed to understand and design for nuanced collaborative workflows and new audiences of stakeholders involved in the creative process.

In late 2016, the authors were working on different product initiatives but both realizing the importance of understanding individuals within their organizational context. The authors observed that while product teams needed to be laser focused on their individual products, as researchers they had the unique opportunity to take a horizontal perspective by understanding the effects of creatives’ ecosystems on their individual experiences across products.

With all of this in mind, the authors teamed up to understand the dynamics between not just the different types of creatives working together, but all of the people involved in requesting, approving, and producing creative work in collaborative environments. They proposed a study to create a taxonomy of the roles involved in creative projects that would move the company’s understanding beyond the user/stakeholder dichotomy to a model that would articulate the way creatives engage with a variety of roles active in the design process. They also sought to identify explicit and implicit collaboration pain points for creatives and stakeholders in hopes of finding areas where Adobe might add new value to the Creative Cloud offering.

METHODS

Participants

Target roles for this project were determined based on previous case-study and collaboration research that the authors carried out with creative teams at Small to Medium Businesses (SMB) and Enterprises.

Participants included marketers, project managers, designers, copywriters, content strategists, developers, creative ops people, design-managers, assets and rights managers, executives, producers, program managers, as well as legal and IT consultants. In addition to understanding the different needs of individuals involved in creative work, they recruited participants from a wide range of organizations to capture cultural and organizational differences that might shape or constrain collaborative practices, such as; security policies, how project teams were formed, who sat and worked together, and other aspects of our participants lived-experience. Companies recruited represented a mix of industries including banking, healthcare, food and beverage, apparel, and technology. Understanding whether working relationships were primarily in-person or remote, and whether teams were made up of people with a shared skill set or organized cross-functionally allowed us to understand how participants communicated during the process and revealed the challenges people faced around communication and translation of expertise in more depth. Participants were recruited through a mix of snowball-sampling, social networks, and corporate partnerships. The team conducted over 60 interviews with people in roles that interacted with creative projects. The research spanned multiple design disciplines, including; graphic design, branding, advertising, packaging, UX, apparel, and industrial design.

Procedure

The research team took a two-pronged approach in order to understand both the individual experiences of creative professionals and their team members, and also the collective challenges teams face when working together. The primary research method used was in-depth interviews and site-visits with sole participants across many companies in a range of roles. The researchers sat with participants physically or digitally and asked them to give in-depth tours of their daily digital and (when feasible) physical work environments. Walking through participants’ processes in fine-grained detail and delving into the relationships that structured their days provided the researchers with the opportunity to learn the thick (Geertz) details of these participants life-worlds and conduct interpretive work to understand the meanings and motivations that underlay their practices. They complimented this approach with data gathered using a retrospective case study method to help uncover unarticulated organizational challenges that could only be seen when looking across individuals working together on the same project. Together, these efforts provided both depth and breadth to the work. Although the researchers used methods outside of the standard anthropology toolbox, the focus on deeply understanding participants daily life-worlds beyond the narrow lens of product usage brought it into the realm of the ethnographic.

Table 1. Recruiting Breakdown by Role:

| Role | Count |

|---|---|

| Designer | 10 |

| Design Manger | 10 |

| Marketer | 10 |

| Project Management/Operations | 16 |

| Physical Production | 3 |

| Developer | 9 |

| Copywriter/Creative Strategist | 4 |

| Other | 5 |

Independent User Interviews: Roles & Process – The 60+ participants the authors interviewed came from different companies. The interview style was flexible, participant-led, and not tied to a single project. During conversations over video conference, in participants’ workspaces next to their desks, in conference rooms and even in quiet corners during Adobe’s 12,000 person conference, Adobe MAX, participants recalled how they had personally contributed in the making of a past piece of creative work. Although not all of the user sessions were ethnographic (some were by phone), all research participants were asked to let the researchers into their professional life-worlds by screen sharing the digital places they inhabited every-day in which they worked, communicated and struggled.

Keeping the interviews semi-structured and user-driven allowed the researchers to learn over the course of the conversation which topics were most important to different user types, rather than imposing a standardized framework of topics on the users. Many participants also showed the researchers how they participated in creative projects through diagramming their process, team members, or the tools they used for their most important tasks. Through these different forms of communication, the team was ultimately able to understand the unique motivations and needs of different roles during creative projects. This method also allowed the team to uncover the ways that participants’ position within an organization shaped their definition of their work, revealing the ways that what counted as a project were contested and fluent based on position within the organization.

Retrospective Creative Project Case Studies – The team conducted retrospective project case studies with 3 key enterprise customers in order to understand the nuances of team dynamics and unspoken challenges. Participants were selected because they had collaborated on a recently finished creative project together. The team spoke with in-house staff (such as marketing managers, creative directors, copywriters, and digital producers) as well as staff from partner agencies that collaborated on the projects (designers, project managers, account managers, etc.).

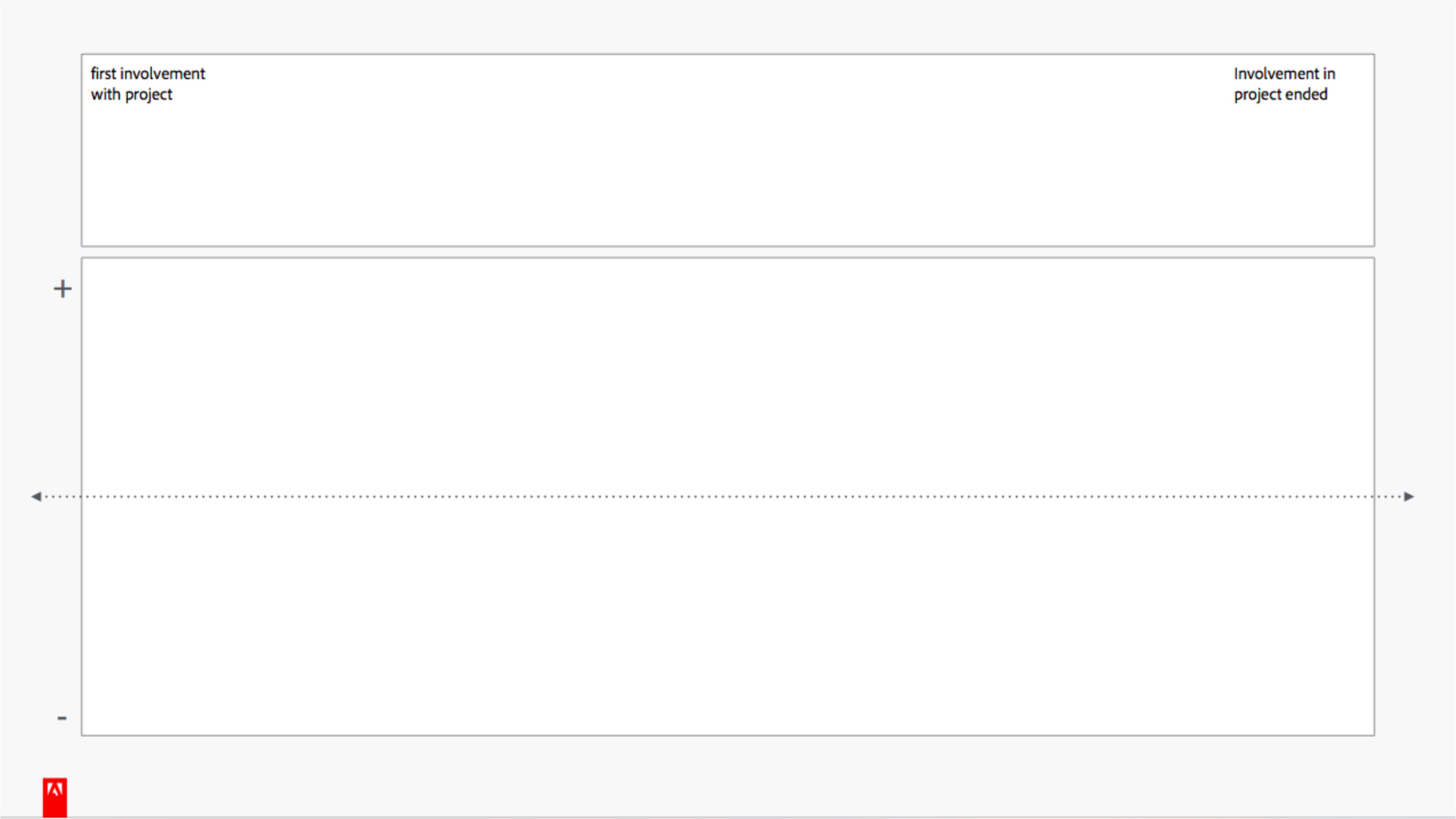

The research team conducted 1-on-1 in-person and remote sessions with each of these participants using a retrospective emotional journey mapping method adapted from the work of Evangelos Karapanosa, Jean-Bernard Martensb, and Marc Hassenzahlcwhen (2012). The journey diagram and line of questioning used guided participants to talk about real events that had happened during the project and directed them away from generalizations. It helped them recall information and got them to talk about their emotions when they might otherwise not have.

Retrospective Journey Template:

Figure 2. The retrospective emotional journey map tool, with a space for key events at the top (timing from right to left) and a space to plot remembered emotional state on the bottom (from high to low).

The researchers also followed a line of questioning to probe deeper into the highs and lows of the experience to identify pain points in key topic areas. Following the mapping exercise, participants were asked to show concrete examples from the project and discuss the tools and workflows they had described using. Later, during synthesis of the data from each project, the mapping method helped the researchers follow a “single story” and connect the dots between the different accounts told by each participant from a given project to also uncover unarticulated pain points.

The benefit of exploring past experiences in this way versus running a longitudinal ethnographic study had to do with a number of factors. For one, the retrospective emotional journey method allowed the research team to collect data quickly while maintaining a wide scope of information. This method also alleviated privacy concerns for participants who were often working on confidential initiatives. The focus on past work allowed participants to show more of their work as projects had often already shipped and the participants felt less constrained in speaking about their processes and experiences than they would walking outsiders through work in progress.

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND INSIGHTS

As the researchers began to synthesize the vast and varied qualitative data they were collecting, they realized they couldn’t understand how the different project roles interacted without understanding the forces and incentives that shaped how the individuals and teams behaved. They saw two key themes emerge from the narratives participants shared:

- Constant struggles about organization and coordinating projects to make sure everyone knew what they were doing and did their part correctly.

- People being asked to do more with less on tighter and tighter timelines in a relentless drive for efficiency that left little space for creative unpredictability and exploration.

Regardless of their role, most of the informants described an intense pressure to work as fast as they could, feeling constantly stressed and overwhelmed by many small kinds of disorganization including tight deadlines, missing materials, and not having what they needed to do their work at critical times.

To understand why, the researchers found themselves in the surprising position of using critical feminist theory to find business insights. The framework that emerged from their data was built on the foundation of theory from Lindsey’s time as a feminist scholar and women’s studies instructor, as well as Jenna’s deep understanding of business needs and processes and the lived reality of producing creative work under late capitalism.

Lack of coordination as a symptom of gender ideology and gendered work

Across the large companies and agencies researched, project management positions involved unacknowledged care work. One agency project manager interviewed described how to get a powerful man on her team to provide feedback on images, she had to lay them out on a table, physically walk him over from his desk and sit with him while he chose the images. She described sending the creatives on her team email invites to meetings as the first step, one often followed by individually reminding them to go to their meetings, either through a digital reminder on Slack or email, or by stopping by their desk. Without her, nothing happened. She explained, “If I need the creative director to review images for a project, I have to go lay out all the images on the conference room table. Then I have to walk with him from his office to the conference room and sit with him until he’s done selecting images, otherwise it will never happen.”

Similarly, at one large corporation, the project manager’s primary role was managing requests and feedback to design. They controlled who could ask for design work, made sure requests were done correctly, and managed the flow of creative work and feedback, protecting the designer’s time and attention, recording information for them and putting it where the teams could find and access it. While this work was critical, it was often under-acknowledged, and the labor of coordination, including meetings and complying with project management guidelines, was almost universally despised and many individual participants (outside of the project management discipline) dreaded it and avoided it at all costs.

Significantly, this research revealed that administrative labor was universally coded as “project management” although it included a large and unspoken element of clerical and secretarial work. Women first started working in offices as “typewriters” during the civil war, and by 1950 secretaries, stenographers and typists made up the largest group of American working women (Berebitsky 2012:9). These tasks are firmly coded as feminine in mainstream American culture. These feminine jobs have historically been targeted for automation and replacement with technology, beginning with the typewriter and continuing with the replacement of secretarial and project management coordination work with project management and task tracking software.

However, the research done for this project revealed that coordination and what Hardt called “affective labor” (Hardt 1999:90) could make or break whether creative projects got delivered successfully, and revealed the ways that the (almost exclusively female) project managers interviewed not only provided information, but also did exhausting affective labor for their teams. Affective labor, while hidden and intangible, is central to material labor, and is part of the costs of production. The replacement of these roles with technology represents not only the feminization of these roles, but provides an example of how companies externalize costs onto their workers. In this case, the cost is the investment in time and emotional labor needed to coordinate successful work across disorganized groups made up of fragmented organizational structures. Through controlling timing, resourcing and scheduling, project managers controlled the conditions of production for creative teams. However, they did not have autonomy; on the contrary, they were constantly squeezed between executive and client demands for efficiency and creatives’ need for unpredictability and desire for exploration time.

Lack of coordination caused the biggest headaches for the participants in this study, regardless of project roles. The depriortization of care work manifested in late and missing requirements, shifting timelines, delays in getting feedback, and lost creative work, among other things. Understanding the feminized history of care work and secretarial labor allowed the researchers to unpack the seeming paradox between the centrality of project management to the success of creative projects, and the explicit devaluing of that same work expressed by many of the participants during the study. Participants viewed tasks of coordination as separate from the creative work, although good and caring project management was often the difference between success or failure.

“Do more with less” and the drive for efficiency

Before this study, the researchers hadn’t questioned the devaluing of project management and care work. Like most modern office-workers, they viewed secretarial and administrative staff as a luxury, nice to have but not essential. This research led them to the opposite conclusion, that the lack of administrative staff and the devaluing and shifting of their work led to pervasive problems across creative projects and organizational roles. This insight demanded further analysis to understand what was causing this apparent contradiction.

The answer came from thinking beyond the scope of the individual roles, projects, teams, or organizations. The researchers found themselves faced with understanding the capitalist imperatives for efficiency. This study revealed environments where professional creatives and their collaborators work in a context where their baseline M.O. is rushed, overwhelmed and overworked. Participants described being incentivized to focus on executing as quickly as possible and thus de-emphasizing collective goals. Because of this, “official” processes and tools are often ignored as individual contributors look for ways of maximizing their own productivity (new features, tips, and tricks) vs. the productivity of the organization as a whole.

No student of capitalism would be surprised to learn that the interests of the workers and the interest of capital end up at odds, this insight dates back to Marx’s foundational 19th century work (Marx 1848). These opposing forces rarely need to be called out in product research. These conflicts surfaced because the researchers took an ethnographic approach that encompassed the professional life-worlds and affective experiences and work of their users.

This central misalignment of interests caused a number of productivity problems for the participants of this study and reduced their perception of the quality of their creative work. Most of the challenges people faced during their work came down to the self-service model of automated project management combined with organizational drives for efficiency that continually tightened timelines and starved them of critical organizational support. These were problems software could not solve. The logic of capitalism creates a focus on execution over strategic work that limits the effectiveness of creative teams.

The research team saw this play out on the micro-level of daily life in a number of ways. An interview with an in-house developer revealed the challenges he faced because of the collapsed timelines his team worked under. When asked about what he needed from design to start building and what design “handed off,” he revealed that because of their timeline his team had to start building before the received designs. As a result they were only able to incorporate them in an approximate way. In this situation he received unfinished drafts of wireframes and work-in-progress from designers that he used as a guide to begin his work. However, since the creative work was unfinished, what he was building was continually in flux and he had to do a lot of redundant work revising the product as the designs and specs changed overtime. He was very uncomfortable with this situation and the developers on his team felt wrong about building in that way. However, because of the production timeline, they needed to start building while the design team was working. This overlap of design and development timeframes meant that they had to make time for extensive meetings to review changes with the design team and discuss how to fix things that they had built incorrectly. He expressed embarrassment during the interview as he discussed his process with the researcher. For this developer, the drive for efficiency that demanded they started building before the designs were complete meant extra work and time spent, as well as an incredibly stressful work experience. However, from his company’s perspective, this seemed like an efficient way to “save time” by having development begin on schedule even in the face of design delays.

Companies try to reduce complexity by narrowing responsibilities of end users and focusing them on specific specialized tasks. However, end users need to understand the broader context they are working within in order to avoid unnecessary changes later. There is a related conflict between corporate transparency and accessibility of assets and end users needs to have for work-in-progress (WIP) spaces. In the end, the research articulated different relationships and workflows involved in the creative process and described nuanced differences between how these different roles relate to and interact with one another.

IMPACT & CONCLUSION

The product development work informed by this research is ongoing and can only be shared in a limited way. However, the overall impact of the work at Adobe can be discussed in more depth. This research took approximately 6 months of additional presentation and socialization to be adopted by the core product audiences. Product teams that were used to focusing on narrow user groups needed help learning how to think horizontally and view people in the broader context of their professional lives. The amount of data in this research made it challenging to present. The team solved this problem through creating two large presentations based on their findings from this research:

- An overview of collaboration challenges and recommendations that spanned almost 100 slides.

- A taxonomy of key project roles that described the roles involved in creative work as well as the challenges these people faced individually and working together.

These artifacts went into Adobe’s internal database, where they “went viral” and have been downloaded over 300 times. Although the research team did this program of study for design and product needs, this framework is also being adopted by other teams. Adobe stakeholders across the company, from executive leadership, to business-development and marketing, have found these reports and reached out to the research team for help adopting the frameworks and incorporating the findings into their business initiatives. This work has spurred not only new ways of thinking about people involved in creative work externally, but also improvements in internal processes and organization at Adobe, which is of course also a creative enterprise. At a high-level, here are some of the ways this research is re-shaping how Adobe thinks about enterprise collaboration and creative work:

Understanding the misalignment of interests between businesses and their workers under modern capitalism and how that manifested in day-to-day creative work pushed the company to think more critically about users and how they differ from customers. Teams ask what are the corporate “customer” needs vs. employee “end user” needs.

This research also spurred reflection about the macro impacts of technology and discussions and questionings about the social and personal impact of certain product development decisions. That conversation is ongoing and ties in with the larger movement of ethical design in technology (Montiero 2017).

One profound impact of this research was organizational rather than manifest in product. This research showed the value of in-depth ethnographic studies that encompassed entire teams and creative processes. Since this research was not focused on how people interacted with a specific product, it could be picked up and used by many teams across the company.

Through this study, the research team has also been able to demonstrate the predictive strength of exploratory research that can often be written off as “too general.” Since the release of these reports, multiple prototype evaluation studies have been conducted, resulting in findings that the authors predicted based on what they had learned about creative teams during this ethnographic work.

This work has also contributed to changing the way Adobe product and design teams work together. Research is agnostic and can play a key role in aligning teams early on through exploratory research. Although the researchers had hypothesized that things like workplace culture, industry, and team dynamics would shape people’s needs, they learned that the impact of social and economic forces outside of individual organizations had much deeper and broader-reaching impacts on how work was accomplished than they had imagined at the outset of the project.

Lindsey Wallace, PhD is a Researcher on the Adobe Design Research and Strategy Team. Email: Lwallace@adobe.com.

Jenna Melnyk is a Senior Researcher on the Adobe Design Research and Strategy Team. Email: Melnyk@adobe.com

REFERENCES CITED

Karapanos, Evangelos, Jean-Bernard Martens, and Marc Hassenzahl.

2012 Reconstructing experiences with iScale. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, Elesevier.

Tzanali, Rodanthi

2011 (Dis)organized Capitalism in Encyclopaedia of Consumer Culture, Publisher: Sage/CQ Press, Editors: Dale Southerton.

Marx, Karl.

1861 “Formal and Real Subsumption of Labour Under Capital. Transitional Forms.” From. Marx’s Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, pp. 93 121.

Marx, Karl & Frederick Engels.

1848 Manifesto of the Communist Party Marxist Internet Archive

Montiero, Mike

2017 A Designer’s Code of Ethics Mule Design

Hardt, Michael.

1999 “Affective Labor.” In Boundary 2, Vol 26.2 1999 Duke University Press

Wallerstien, Immanuel

1979 The Capitalist World-Economy Cambridge University Press