What’s the first thing to do if, at the end of your work day, you come home to your apartment and see a river of water flowing out from under the washroom door, threatening to harm your home and your downstairs neighbor’s? Do you start to clean up the mess while the water keeps flowing? No, you shut off the water first. Only then do you attend to the damage.

Ninety-two people are killed by firearms each day In America, a flood of deaths in the US each year that rivals the number of deaths from traffic accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Japan, and in the UK as well as elsewhere in Western Europe, you are considerably more likely to be struck by lightning than to be killed by a gun.

There are plenty of people everywhere who have issues with anger management, macho crises, impulse control, or more severe mental health problems. But if the most lethal weapon they have at hand is a rolling pin, or even a kitchen knife, and not a firearm, acting out has far less harmful consequences.

Over the past several weeks I have been thinking harder than usual about the unabated torrent of shootings in the US, gun control, and the nature and extent to which our research, design, evaluation, and strategic management services can make any meaningful contribution to removing the health and safety menace posed by firearms. As Hillary Clinton said when she accepted her party’s presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention, this doesn’t involve taking everyone’s guns away from them, or repealing the US Constitution’s Second Amendment. But it may mean taking steps to prevent people from being “shot by someone who shouldn’t have a gun in the first place.”

I was intrigued to learn from Evan Osnos’s recent New Yorker piece about the business and politics of selling guns that the “story of how millions of Americans discovered the urge to carry weapons…begins not in the Old West but in the nineteen-seventies.” The implication is that guns are not so indelibly etched in the collective psyche that they can’t be dislodged. At the same time, in Osnos’ view, the gun business has a big problem—guns last a long time. So the industry has had to continually find new customers or new ways of selling more guns to old customers (he credits Samuel Colt with coining the phrase “new and improved”). They have tended to pursue existing customers, but facing a two-pronged threat from foreign competition and a decline in the once-reliable hunting market, the US gun manufacturers turned to fear marketing. And it has worked. Self-defense, tinged with racism and xenophobia, has been a persuasive strategy for more than two decades.

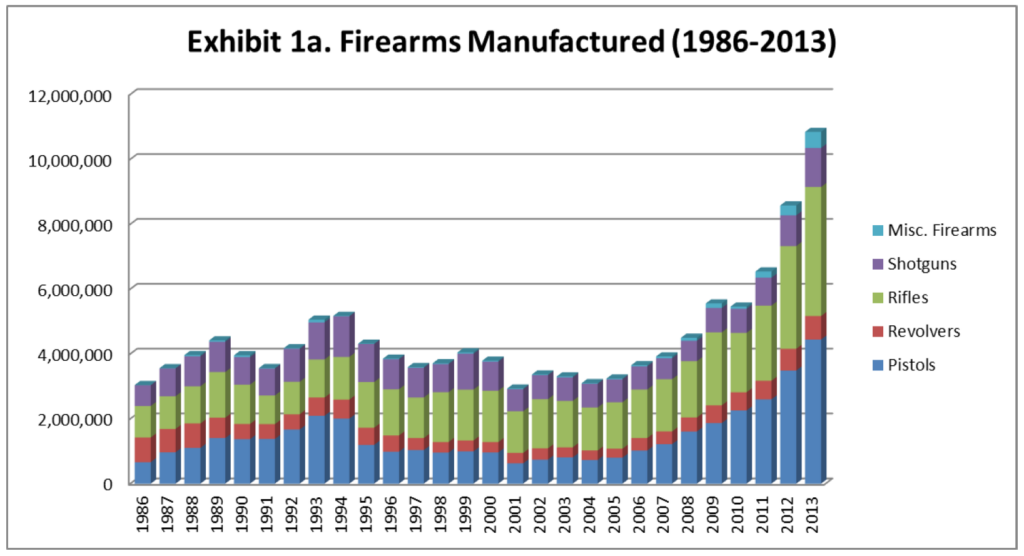

According to the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, US firearms manufacturers have enjoyed a more than doubling in the number of arms manufactured for civilian (i.e., non-military) uses from 2010 to 2013 (the latest year for which reliable data are available). Less than 5 percent of these millions of firearms are sold for export every year. As Robert Dolan pointed out in the Harvard Business Review earlier this year,

“in the three years since December 2012 (the date of the Sandy Hook, [Connecticut] killings) the US-based “Big 3”—Ruger, Remington, and Smith & Wesson—collectively generated over $2 billion in gross profits as they sold about 45% of guns in the US. Investors also did well: A $100 investment in Ruger in late 2010 was worth $443 in late 2015, while the equivalent investment in the S&P 500 yielded only $163 over that time frame.”

I am not sure which disturbs me more—that such levels of fear exist, or that they can be exploited so successfully to sell guns. This is a crystal clear case of social marketing – where marketing approaches have been applied to change behaviors in the name of societal benefit. But the increased (rather than decreased) threat to public safety is an unintended consequence, and calls out for attention to core business issues like strategy, innovation, and value. Business ethnography has the potential to help tackle one of the more pressing social issues of our time. I think the EPIC community is up for a challenge. It is truly heartening to see that on this year’s EPIC conference in Minneapolis we will have the tutorial “Ethnographic Thinking for Social Change” taught by led by Jay Hasbrouck and Charley Scull and the salon “Working for Social Change,” convened by Chuck Darrah and Jeanette Blomberg.

Are any among us interested in teasing apart the laminated layers of racism, xenophobia, fear marketing, guns and shooting that might produce insights that ultimately reduce the risk of gun violence? This may involve crossing lines, professional and personal, that we use to separate ourselves from discomforting worlds. And as Luis Arnal reminded us in his EPIC2015 keynote, we all have lines we will not cross.

I truly don’t have a ready answer. But I do believe we have a useful diagnostic toolkit, one that helps us understand the perceptions of risk and hazard that make people susceptible to fear marketing. Risk perceptions (what harm can come from X?) are the result of well-established group value orientations having to do with liability, equity, consent, and time.

Liability is a value orientation concerned with what is supposed to happen if something goes wrong. Who will be held accountable for making restitution or compensation? How will I be made whole again? Is this a shared responsibility, or placed at the feet of the party with the greatest ability to pay?

Equity is another word for “fairness”: Is everybody treated absolutely equally, regardless of need, rank, status, and/or historical disadvantage?

Consent is a value orientation that has to do with how we expect to reach agreements with one another. Does everyone have to agree or does a majority rule? Is agreement implicit, or does it have to be explicitly “talked out” or negotiated?

And time in this context refers to a value orientation about how far out into the future do contemporary events retain their importance? How far back in history is so long ago that it doesn’t matter anymore?

If we can learn about these value orientations that support collective fears, we may gain some leverage to counteract them. And such leverage can only help us gain greater traction in our pursuit of healthier, safer, more socially just and sustainable futures.

See you in Minneapolis in a few short weeks!

Images: 1. Wooden rolling pin #1 by photochem_PA via flickr, CC BY 2.0; 2. Firearms Commerce in the United States, a Statistical Update, 2015, United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

Ed Liebow is the executive director of the American Anthropological Association and an anthropologist with a history of environmental health and social policy research. In a previous incarnation, he served as EPIC’s treasurer and proceedings coordinator. ELiebow@americananthro.org

Ed Liebow is the executive director of the American Anthropological Association and an anthropologist with a history of environmental health and social policy research. In a previous incarnation, he served as EPIC’s treasurer and proceedings coordinator. ELiebow@americananthro.org

Related

Working for Social Change, Chuck Darrah

A Seat at the Table of Social Change through Service Design, Jeanette Blomberg & Chuck Darrah

0 Comments