This paper assesses listening from an ethnographic perspective and demonstrates its value and applications across all phases of research projects. Although listening is foundational to ethnography, it is typically understood as a passive method or pathway to receive information and take notice of the world. In fact, listening is active and multifaceted, and should be deliberately cultivated as a skill, methodology, and creative practice. This paper both informs and provokes professional ethnographers and researchers to explore unique ways that ethnographers listen, how listening-based methods can be integrated into all steps of a professional research project, and how listening practices of artists, musicians, and sonic activists can inspire new directions and forms for our work. Examples of listening-based methodological innovations are documented, as are suggestions for further avenues for creative exploration.

In early 2020, I was working on a yearlong ethnographic team project on Latino voting practices in Texas among eligible citizens. The project was envisioned and led by my colleague, Cecilia Balli, PhD, founder of Culture Concepts. After completing over 100 ethnographic interviews in 5 sites, the vast majority conducted by Cecilia and Monica Lugo, PhD, our small team was deep into analysis when the pandemic escalated. Our client, the Texas Organizing Project Education Fund, requested we reach out to only the non-voters previously interviewed to find out whether the pandemic and its government responses changed their perspective on voting practices. It did.

Two things became clear in these follow-ups. First, we reconfirmed an initial insight, that these non-voters felt politically disempowered and lacked a sense of belonging to American political life. They believed politicians did not listen to them; their voices were effectively silenced. This sentiment was echoed in many interviews with Texas Latinos, whether voters or not (see Balli, Powell, Lugo 2020). As one Latina who only recently began voting explained:

The reason why I haven’t voted is because I was always raised like, ‘It doesn’t matter if you vote. It doesn’t matter if you speak up because they’re never going to listen to you. You’re a minority, they’re always going to see you as less.’

(30)

People who found a pathway towards empowerment and belonging—often through connection to social institutions found in education, local communities, politics, or work—were more likely to vote. As we explained, people who vote tend to feel “they have a right to be heard, they believe they can influence political outcomes, and they’re able to directly relate government policy to their lives” (21).

Second, we found that listening closely to these citizens and prompting them to articulate their perspectives on political behaviors made a tangible change: many nonvoters now planned to vote as a result of the Culture Concepts ethnographic interviews. One nonvoter in San Antonio explained, “Maybe it has a lot to do with the conversation and the interview that I had [with you], to just bring awareness [that] our vote does matter” (90). And another stated, following a logic that echoed patterns of inquiry during the interviews:

Yes. I voted in the primaries. I think our last interview motivated me to be more active in that. I did my research and I was very proud of myself…I think it was thinking about the types of candidates that I want to see in office, and if I don’t actively participate in trying to put—even if it’s not the ideal person, or somebody who is completely aligned with what I want to see or what I believe—being able to choose somebody, even if they don’t get elected. Like, ‘Okay, well, I made an effort. I didn’t just allow somebody else to make a choice for me or completely disregard this opportunity that I have.’

(90)

This was a surprising result, because our ethnographic interviewing methodology steered researchers away from judgmental positions and our interview guide made no suggestion to vote. In sharing our research agenda, we simply explained that we were trying to understand voting proclivities among Latinos. But the impact was also counter-intuitive in a more fundamental way: How could listening provoke change like this? Isn’t listening a passive act?

Regardless of this common sense, our final report recommended that future voter outreach programs prioritize “authentically listening to the political interests and everyday challenges of Latinos” (5). Rather than telling people to vote—a message participants had been hearing for many years—a more effective pathway to voting might be found through listening.

The voter study prompted me to investigate listening more deeply and explore some fundamental questions about the nature of listening. This paper represents a first step in that exploration, an examination of ethnographic listening from an ethnographic perspective. My guiding theme is that while listening is typically understood as a method or pathway to receive information and take notice of the world, I have found instead that ethnographic listening is unique and potentially productive. Not unlike the way some words and utterances are understood by linguists as performatives (Austin 1962), we might similarly recognize the capacity for ethnographic listening to do things in the world. This paper points to ways ethnographic listening might do things. It addresses why professional ethnographers typically don’t pursue these avenues despite recognizing the foundational nature of listening to our work and, most importantly, how we might deploy our unique style of listening in diverse ways.

I understand “ethnographic listening” as a multi-dimensional process of knowledge-production, which has the capacity to produce reciprocal insights for our research participants and partners. This is not to say that ethnographers are “better” or more empathetic listeners, it’s that we listen in particular ways. Ethnographic listening is activated in different modalities of methodology, data collection, and analytical thinking, especially through interviewing, engagement with soundscapes, and concentrated attention or thought given to research data. Listening in this way doesn’t only happen during research, but can potentially be deployed in multiple locations and points of our process.

This concept iterates on what Forsey (2010) has called the largely unacknowledged practice of “participant listening” in ethnographic research, which he distinguishes from the traditional legacy of participant observation—a long cherished but increasingly outdated and imprecise description of what most ethnographers actually do in fieldwork, especially in contemporary “interview societies” (Silverman 1997, Gubrium and Holstein 2002) where social interactions are often “spatially dislocated, time-bounded and characterized by intimacy at a distance” (Forsey 2010: 566, referring also to Hockey 2002: 211, Passaro 1997). This concept of ethnographic listening is inspired by, but not limited to, ethnographic interviewing methods, particularly in the distinction between ethnographic interviewing and extractive approaches of data collection found in other, more structured research methods. Rather than extracting information from participants, ethnographic interviewing ideally relies on the co-creation of emergent concepts and the mutual production of knowledge (Briggs 1986, Gubrium and Holstein 2002). In an ideal version of this relationship, ethnographers might hope to serve as a guide, helping research participants explore territories of knowledge they hadn’t given much thought to, had taken for granted, or may simply struggle to put into words.

Through innovations in research design and methodology, we might position ethnographic listening to more intentionally create opportunities for reciprocity. Even when the interests or agendas of our research goals and research participants diverge, ethnographic listening encounters may nonetheless generate unwieldy insights for participants. The act of listening is core to the possibility of what might be unleashed. This aligns with what Paul Ratliff has called “collateral revelation” in his enduringly honest PechaKucha from EPIC2014, which pointed to the unintentional impact of many professional ethnography projects on research participants:

We don’t go into the field to midwife individual discovery or revelation, and this may be why we don’t notice how often it happens. We change people. We change their minds, their behaviors, their understanding of themselves.

(Ratliff 2014)

Through listening, ethnographers can similarly feed back into our participants’ thought processes, potentially energizing domains of local knowledge and helping draw connections that had not yet been fully associated. And this same reciprocity might also feed back into relationships with our clients, stakeholders, partners, colleagues, and others in the organizations we work for or with.

Listening is an ethnographic superpower, and in this paper I will point to ways we might harness this energy. The first part of this paper synthesizes EPIC community perspectives on listening, based on original research. That includes formal and informal interviews with more than two dozen practitioners, in order to gather a diverse range of perspectives on how we listen and develop a subject model of ethnographic listening. I also produced EPIC events focused on listening to gauge community responses, as well as developing and leading an EPIC course on ethnographic interviewing. And to prompt further analytical discussion and reflection, I organized an EPIC-sponsored panel on ethnographic listening at the 2023 Society for Applied Anthropology conference. I am deeply grateful for the wealth of insights that the EPIC community has shared with me about listening, which has inspired deeper investigation, and especially the willingness of some individuals to participate in experimental listening methods described below.

While Part One of the paper on existing practices makes sense of ethnographic listening and demonstrates its value, the section also suggests the inherent frictions that prevent us from highlighting or even fully accepting our role as listeners. Part Two is a prompt and provocation for professional ethnographers to consider new directions and new forms for listening, including directions inspired by the work of artists, musicians, and sonic activists. Specifically, I will explore the unique ways that ethnographers listen and consider how listening-based methods—traditionally framed as a mode of data collection—might be integrated into all steps of a professional research project. At the end, I provide examples of listening-based methodological innovations I have orchestrated and suggest further avenues for creative exploration.

THE SOUND OF FRICTION

On the heels of the Latino voter study, I connected with the Practica Group to work on ethnographic research projects. That’s where I met Michael Donovan, PhD, Founding Partner at Practica. We worked on numerous projects together, based on ethnographic observations and conducting dozens of interviews together.

More than a year prior to this essay, as I was forming my research project around ethnographic listening, Mike was one of the first ethnographers I spoke to. He found the concept fascinating (as a curious person at heart, this was often the case!). And so I asked him, “You’ve been doing this kind of work for a long time, do you consider yourself a professional listener?”

“No,” he replied, eyebrow raised. “I never really thought of myself that way. But it could make sense. I don’t even know if I’m a good listener.”

“Mike, I’ve sat in on so many interviews with you. You’re one of the best listeners I’ve ever met!”

We talked then, and in later conversations, about ethnographic listening, as well as the ways our projects, proposals, and conversations with clients tended to obfuscate listening—a skill which we both agreed is fundamental to ethnography.

In late 2022, Mike died suddenly. In his obituary, written by his family, I was heartened to read, “Michael had a capacity to listen with deep empathy and to discover underlying meanings and connections.” Mike was truly masterful at the craft of ethnography and his instinct for listening was felt, if not always foregrounded.

I write about Mike Donovan because a lot of the EPIC community shares his acumen (even if he was a better listener than most of us). Despite our listening expertise and the foundational nature of listening to our work, most EPIC practitioners don’t highlight listening for colleagues, stakeholders, organizations we work with, clients we work for, or even for ourselves.

This section outlines that tension among professional ethnographers which emerged during my research. Listening is essential to our work, but we don’t typically describe our work through the lens of listening. Why the friction?

In talking with the EPIC community, two consistent themes quickly emerged—and a third underlying theme lurked near the surface. First, all agree: listening is a core skill. As one ethnographer put it, “listening is foundational to what I do.” At the same time, listening is not part of how we represent ourselves, identify our work, market ourselves, or develop our projects (with just one exception among dozens interviewed). By and large, we lack the vocabulary to explain listening and what it might do for us.

A third underlying theme is that ethnographers tend to understand listening primarily through an inward lens. We recognize ourselves as listeners, but rarely acknowledge the impact our listening might have on others. Put another way, we know listening changes the ethnographer, it is felt deeply. But we’re unsure if our participants or colleagues share a similar response. We rarely consider and may frequently underestimate the ways our careful and concerted listening practices can be framed as relational, situated, and integral to the co-production of knowledge with our subjects.

Practitioners don’t necessarily define themselves as “good” listeners, rather they point to a loose sense that ethnographic listening is distinct. Through experience and training, they have cultivated a style and a distinctive way of listening, or what might be called a “genre of listening” (Marsilli-Vargas 2022). For instance, one ethnographer explained, “It’s very difficult to empty your mind and leave yourself open [for listening].” Another struggled to explain to what makes their style of listening distinct:

Listening is an invisible skill. Most of my clients just think I’m a sociable, friendly guy. And I am, but it’s not as easy as it looks…As listeners, as ethnographers, we’re weird mediators of sorts. Ideally, we’re unnecessary. Our job shouldn’t even be necessary. Listening should be easy.

More generally, these statements suggest something deeply elusive about the listening process. One ethnographer called it “mysterious,” even. Lacking a shared definition or vocabulary for making sense of listening, ethnographers instead pointed to dynamic processual, structural, and relational descriptions. One practitioner explained listening in terms of care and willingness to learn from participants:

I was changed by listening…What do we talk about when we talk about listening? Listening is love. It’s collaboration… Don’t listen unless you’re willing to be changed. You have to be open, receptive. You have to be willing to say: what they’re telling me is true, just believe.

And for many professional ethnographers, the force of listening is especially felt through the way that listening engenders and embodies reciprocity:

Listening is a kind of gift. You’re giving them your ear…People will unburden themselves to a stranger’s ear…You take on a lot of the other person’s emotional load.

This then is perhaps the ideal and aspirational goal for ethnographic listening: to build relationships defined by mutually beneficial exchange between researchers and our research participants.

Listening is often a deeply emotional experience for ethnographers, rooted in patient engagement with the people, practices, and environments we study. As such, there is a meaningful resonance in listening, an instant recognition of some cultural and emotional weight. Clifford Geertz has described this type of “force” as, “the thoroughness with which such a pattern is internalized in the personalities of the individuals who adopt it, its centrality or marginality in their lives’’ (1968: 111). The anthropologist Renato Rosaldo, noting that ethnographers tend to prefer data that participants can explain in depth, nonetheless wonders, “Do people always in fact describe most thickly what matters most to them?” (1993: 2) Listening often feels that way for professional ethnographers: fundamental, but hard to put a finger on.

At the same time, listening is at odds with some long standing Western cultural traditions and epistemological discourses, as well as powerful narratives core to corporate culture and capitalism, more broadly. In particular, the sound of friction is found in the discord between perceptions of listening (arguably, misperceptions) and the value placed on productivity and rationality in the organizational settings where professional ethnographers work.

In considering broader contextual factors, scholars of listening and sound studies have outlined a longstanding bias in Western culture and philosophy that prioritizes vision over other senses. The lineage of this perceptual and epistemological prejudice, called ocularcentrism (Berendt 1985, Back 2007), stretches back to classical history: Plato and Aristotle gave primacy to sight, and associated it with reason. The logic of listening has long represented an unsound form of rationality.

These cultural tendencies persist to the present day, as ethnographers pointed out to me many of the subtle linguistic metaphors and stereotypes that generate friction around listening. We say that “seeing is believing.” Or when we discover truth, “I’ve seen the light.” When we want to relate to an individual we might say, “I hear you,” but when we come to a more profound realization we say, “I see.” We trust the eyewitness, but condemn hearsay.

This cultural legacy emerges in corporate settings, too, as noted by professional ethnographers. The business world tends to valorize talkers, producers, the “outspoken” individual. Being too much of a listener can feel like waffling, the essence of ambivalence, which frequently runs contrary to models of business leadership.

Further, the pace of ethnographic research is often not in harmony with the rhythm of organizations (Cefkin 2007). And ethnographers don’t necessarily want to draw more attention to this dissonance. Listening is a slow, deliberate, demanding activity—even if a pursuit with the capacity to create change and generate insights. This slow rhythm pushes against the endless urgency of agendas and timelines for organizations we work with. In theory, they invite us to do our work and spend time listening and capturing the voice of the user or consumer. But in actual fact of practice, professional ethnographers have recognized that organizations bristle at the slightest perception of inaction or inefficiency. And the uncertainty of listening—how long will it take? what will actually be uncovered? how do you do it? what is the impact?—all resist the capitalist logic of organizations, which revolves around productive power.Ironically, outside of corporate research departments, a proliferation of books and articles in popular psychology, journalism, and the business press have begun to highlight what might be called a contemporary “crisis of listening” (e.g. Murphy 2020, Trimboli 2022). These authors argue that we have become “bad” listeners and need to (re)learn “good” listening. Much of this work is framed around a critique of the attention economy, though the factors are certainly more complex. They argue that our livelihood and our happiness, if not our souls, require us to rediscover the “lost art” of listening. An emerging group of experts is now teaching people, including those in the business world, how to be better listeners.

HOW TO DO THINGS WITH LISTENING

Doing things with listening requires we dispense the notion that listening is a passive act, limited to giving attention and gathering information. Similar to performative statements and utterances, in which words take on the power to do things (Austin 1962), listening might also be seen through the frame of performativity. Ethnographic listening, whether consciously situated or not, has the capacity to do things, which may include: inspiring people, generating discovery (personally and collectively), producing culture, and aligning people (as a community or with an environment). Further productive capabilities will likely be revealed through ongoing experimentation.

In this spirit, I’d like to look at the way ethnographic researchers “do” listening, and then consider how listening might play a larger role in our work as professional ethnographers. I’ll share some experiments with listening that have been conducted by myself and others in professional contexts. And I’ll also outline a conceptual framework to prompt further experimentation.

Throughout these experimental prompts and conceptual framework, I want to highlight the artists, musicians, composers, and sonic activists whose work has inspired these methods and listening interventions. In particular, the extensive body of work and writings from Pauline Oliveros is foundational (Oliveros 1998, 2005, 2010, 2013). Her deep listening practice and soundmaking scores, called Sonic Meditations (1971), serve as an archetype for transforming listening into action. I also have been energized by the artwork and insights of Elana Mann, a Los Angeles-based artist exploring the power of the collective voice and the act of listening through sculpture, sound, and community engagement. Mann’s soundmaking tools/sculptures palpably demonstrate the ways listening can intervene and transform social contexts. Other art inspirations include the Houston-based non-profit group Nameless Sound and their experimental soundmaking pedagogy (Dove 2016); the d/Deaf director and artist Alison O’Daniel, and her work leading to the cinematic project The Tuba Thieves (2023); the musical group/artist collaborative Lucky Dragons, exploring ecologies of participation and dissent through sound performances, publications, recordings, and public art; and many others. Over the last several decades, and increasingly in recent years, many artists have positioned listening as core to their practice, to powerful effect (e.g. see Ennis 2018, in conversation with Elana Mann). It’s an exciting moment for professional ethnographers to consider doing the same.

These listening experiments also build on prior work by members of the EPIC community.

That includes Gregory Weinstein’s (2019) prompt to explore listening “through the ears” of blind research participants in the service of more inclusive research methods and design outcomes. Melissa Cefkin (2007) has decoded the “rhythmscape” of the corporate sales pipeline through careful ethnographic listening and work shadowing. Cefkin and ken anderson co-organized the EPIC2007 conference around the theme of “Being Heard,” though focusing on how professional ethnographers can be heard in their organizational settings (Cefkin and anderson 2007). Another emergent and growing body of literature from the EPIC community, as well as many academic anthropologists and related social sciences, has explored the role of the body in knowing and the possibility of a multi-sensory ethnography (e.g. Roberts 2020, Lee and Chao 2021; academic references on embodied listening include Feld 1990, review articles such as Lock 2017).

The EPIC2022 conference in Amsterdam represented a fascinating touchpoint at the intersection of listening and professional ethnography. The artist Grant Cutler produced an immersive experience on-site called “Silence: Divergent Listening in the Anthropocene” (Cutler 2022). David Goren presented his ongoing research on Brooklyn pirate radio stations (Goren 2022). In the lead up to the conference, I hosted one of Oliveros’ “Sonic Meditation” events for an online group, which led to engaged discussions. And at the outset of the conference, Gregory Weinstein and I co-hosted a SoundWalk that led a group of EPIC members meandering through the streets of Amsterdam (more on this event below).

How Listening Gets Done

Simultaneous and multidimensional listening, particularly during interview encounters, characterizes an ideal form of ethnographic listening. In my research, professional ethnographers explained to me how they listen for multiple signals, as well as opportunities for guiding conversations and making sense of patterns. Jay Hasbrouck has similarly pointed to the uniqueness of ethnographic listening, describing what he calls “layered listening” which, “might be best described as an internal voice that continually searches for the cultural meaning behind statements people make, and then attempts to find points of interaction that can be used to explore the significance and lived experience of those meanings for participants” (2017:17).

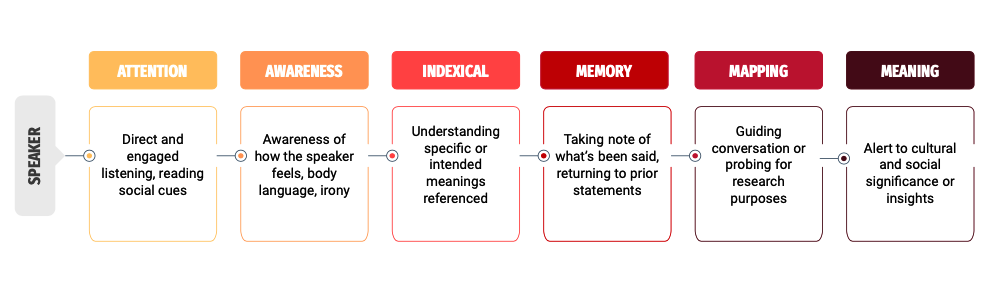

Mapping this multidimensional portrait of listening reveals that ethnographers are not merely “good listeners.” The conventional sense of a good listener—paying close attention to and having empathy for another person—is table stakes for the ethnographer. They must also consider multiple and coexisting processes of attention, sensory dynamics, cultural dynamics, social dynamics, and linguistics (indexical), not to mention methodological concerns, ethical concerns, temporal concerns, and the micropolitical dynamics of the ethnographic encounter. That includes the following dimensions of ethnographic listening which happen concurrently throughout an ethnographic interview:

- Attention: Ethnographers must be clearly engaged in listening; interpreting and performing appropriate social cues that signal listening to research participants.

- Awareness: Ethnographers must pay attention to signals from participants, many of them nonverbal, that communicate how the research participant feels, their comfort level with the conversation or observation. That might also include silences or body language that sends a message, as well as instances where nonverbal cues might be trying to communicate that what’s just been said shouldn’t be taken purely at face value.

- Indexical: Ethnographers must listen for how specific words and categories are deployed in a research subject’s explanation, in order to understand the context and intent of what’s been said. Oftentimes, words or phrases may signal novel or emergent intent, which must be categorized rapidly as potentially either idiosyncratic or shared with various communities of practice.

- Memory: Ethnographers allow participants to guide conversation to a certain extent, but need to be ready to remember both the territory their research or interview guide intends to cover, as well as coming back to specific statements or turns of phrase that a research participant may have raised earlier, sometimes hours or days prior.

- Mapping: Ethnographers need to be cognizant of how an interview or observation is unfolding, in order to map which subjects have been covered and which further topics or questions still need to be covered. Much of this listening is functional in nature, in order to insure the success of a research encounter.

- Meaning: Ethnographers need to be prepared to probe further on specific words, terms, or turns of phrase they hear that have or might have special cultural significance to the research participant, oftentimes meanings that participants assume an ethnographer may or should know about, and which can instantly reshape the tenor or direction of a conversation.

Ongoing exploration and conversation may further add or revise this subject model, but the essential point remains. Further, this subject model suggests that ethnographers are not simply more empathetic listeners than the average person. Rather, we are engaged in a distinctive multi-layered listening practice that cannot be equated or reduced to empathy, rapport, being “friendly,” or any other of the common tropes that seek to describe how ethnographers see the world from a different perspective. These qualities may play some role in motivating listening, but ethnographic listening is rather a multilayered and multidimensional process, an expert skill learned from years of experience.

Integrating Listening into Our Projects

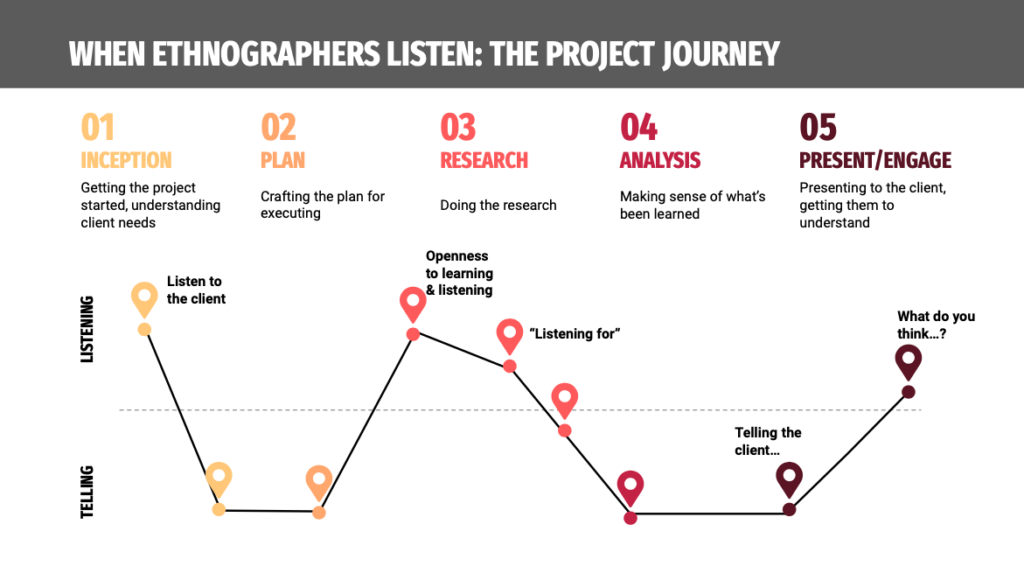

Armed with a better sense of how ethnographic listening works and how it accomplishes research work, I want to look at the existing role of listening in a traditional project cycle for professional ethnographic work in order to imagine new potential roles. Of course, the “project” is a source for continual innovation and may exist in exceedingly diverse situations in profesional ethnographic work (e.g. Fagundes and Gomez 2016, Dautcher and Griffin 2010, Cuciurean-Zapan 2017, and many others in the EPIC community). But for the purpose of this article, I would like to draw our attention to what, in my professional experience, is standard protocol. This begins with project inception, where research is requested or initiated, and research teams engage in conversations with stakeholders or clients to refine the project purpose. In the second stage, the research team crafts a research plan, often in coordination with project stakeholders. The third stage is research, which employs methods for data collection. Analysis happens next, often blurring with or overlapping the third stage, and taking many different forms or directions. Finally, research analysis or insights are delivered back to the initial stakeholders, as researchers seek to communicate their findings and often engage in conversation to understand implications and next steps.

In most projects, listening happens mainly during the Research phase. We may also spend considerable effort listening during the inception of a project: trying to understand where the client is coming from, their concerns, and what they already know. At the conclusion of a project, especially to understand audience reception and to effectively locate opportunities for integrating research findings and recommendations within organizations, some amount of listening may be required. But for the most part, outside of these occasions, professional ethnographers spend more time telling others what to do and focusing on productive outputs than listening. Even during the research phase, listening skills often fatigue as we begin to discover patterns of assumption and feel that we can essentially predict what participants will say next. Ethnographers tend to stop listening broadly and begin “listening for” certain stories or details that can verify their hunches and hypotheses. At the beginning and end of this overall project journey, too, professional ethnographers may tend to focus more on “selling” their ideas for what a project should look like (inception) and what the organization should do with these insights (presentation). Inception stage listening is often obligatory. Presentation stage listening is often more theater than sincere. Even Research stage listening can fall into the trap of feeling more like extraction than genuine openness.

As a provocation, we might consider: What if we could integrate listening at every point along the project journey? What if we could find new uses for listening that might prompt researchers, as well as clients, stakeholders, partners, and/or research participants, to listen or listen in new ways at different points of the project journey?

Below I document two such ethnographic listening experiments, while referencing other projects and pointing to ways that others might generate new methodological directions.

Soundwalk

In 2022, Gregory Weinstein and I co-organized a Soundwalk at the EPIC conference in Amsterdam. We led a group of about 20 ethnographers on a walk from the central train station, through the historic heart of the city, past the Red Light District, and ending at a small park in a more contemporary urban office zone. Prior to departure, we provided some basic notes on the purpose of the Soundwalk and instructions: Pay attention. Don’t speak. Listen deeply. These directives were largely heeded, but not enforced. At the conclusion of the walk, the group participated in a conversation about what they took note of, which included a diverse range of sonic dimensions (e.g. natural and technological sounds), as well as additional sensory inputs, such as sights and smells.

In its most basic form, the Soundwalk is a silent meditative walk in a chosen soundscape environment. The concept originated with the World Soundscape Project under the leadership of composer R. Murray Schafer in Vancouver in the 1970s (Schafer 1994 [1977]). Among other things, Schafer wanted walkers to reengage with their listening capacities, as a pathway to understanding their situatedness. Since that time, various Soundwalk practices have been employed by a wide range of musicians, composers, sound studies scholars, and sonic activists. The basic process is remarkably simple and accessible.

The Soundwalk also represents a malleable form that might be integrated into the professional ethnographic research projects. As a case in point, on the heels of the EPIC2022 Soundwalk, one participant brought the method back to the large technology organization where they are employed and used the practice for several projects. In one instance, the Soundwalk was performed at the outset of an international research gathering as a way to orient cross-functional team members, including non-researchers, and attune them to listening. Here, the Soundwalk set the tone for subsequent interview and observational research, getting people from diverse backgrounds on the same page and calibrating listening. This novel usage of the Soundwalk reveals its potential to shift perceptions and reconfigure sensory prioritization for individuals or a group.

But the Soundwalk’s capacity to do things with listening might expand beyond preliminary and main research phases, and into novel forms of presentation and ongoing engagement. For instance, a group of Danish anthropologists has created a sound-based “energy walk” in the remote landscape of northern Denmark to convey ethnographic research insights to public audiences. Hikers were guided through windy landscapes via recordings that sensitized them to the multiplicity of landscape sounds connected to energy infrastructures found there, and invited participants to imagine potential future environments that looked and sounded different (Winthereik, Watts, and Maguire, 2019). One might imagine how these Soundwalkers could be further engaged in conversations that could potentially re-shape analysis and reception of the work. While not an ethnographic project per se, Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller (2023) have evolved the Soundwalk into a holistic sensory experience that expands into time and imagination. One such work, investigating alternate and past realities, is their Alter Banhof Video Walk, designed for the old train station in Kassel, Germany, in which, “an alternate world opens up where reality and fiction meld in a disturbing and uncanny way that has been referred to as ‘physical cinema.’”

The Soundwalk might be framed as an early stage research and data collection method, one which is highly open-ended and potentially generative. At the outset of research, or perhaps in a pre-research stage, the Soundwalk might be employed for gathering diverse insights and “getting the lay of the land.” As such, the method could be framed as an extension of a multi-sited ethnographic imaginary approach, specifically in the ways it echoes Marcus’ call to “follow” the thing, the person, or the conflict (1995). The Soundwalk might usefully expand to prompt ethnographers to follow the sound, the soundscape, or some meaningful dimension of the soundscape. Jay Hasbrouck (2018) has also suggested that ethnographers consider unplanned pathways through space, perhaps letting sounds or other sensory inputs guide them through dérive, (drift, in French). He describes dérive as, “an unplanned journey through a landscape during which the surrounding architecture, people, and geography direct the traveler’s path and interactions, with the ultimate goal of encountering new experiences and gaining a deeper understanding of their environment” (24). Openness to following as a source for cultural production can also be found in the conceptual projects of artists, most notably Vito Acconci and Sophie Calle. For Acconci’s Following Piece (1969), the artist randomly selected and followed individuals on the streets of New York City, pursuing them until they entered a private building, a project that guided him throughout four boroughs. Recording sensory and cultural data along the way—and with proper ethical research permissions, of course—could potentially yield valuable early stage ethnographic insights.

In these examples and direction prompts, the value of the Soundwalk resides in its possibilities. But unlike many other research methods focused on the extraction of a specific type of data set, the Soundwalk is unwieldy. It’s difficult to know beforehand what direction it will take. Openness to the latent chaos or noise found in the environment is what makes the Soundwalk a provocative example of ethnographic listening. It suggests that listening is a powerful tool for starting to make sense of unfamiliar cultural landscapes.

Community Listeners

“Community Listeners” is an original methodological innovation inspired by ethnographic, artistic, and group listening practices. In a test case for the concept, I worked with a UX research team at a SaaS website design tooling company, with B2B customers. Researchers were at the early stages of generative discovery research with their customers, becoming better acquainted with the diverse contexts of uses for the company’s product line. For the Community Listeners event, we assembled a group of researchers for a dedicated collective listening session(s), focused mainly on the generative research interview recordings of one junior member of the team. That individual researcher was tasked with curating a selection of research video clips—their role at the event was like a “DJ” who selects music: here, coordinating data flows. In this situation, analysis was at a preliminary stage, so the research data and its potential insights were new to the group. We began the event with a discussion about ethnographic listening and did a Sonic Meditation exercise loosely based on instructions from the artist Pauline Oliveros (1971). Subsequent review of videos gave space for listening and unreserved insights, which were, at times, alternately awkward and productive. The awkwardness stemmed from the group’s lack of familiarity with an unrestricted approach to analysis and a full openness to listening for all potential signals—the “purpose” and “objectives” were not immediately clear. The eventual value that emerged, on the other hand, stemmed from mapping insights collected throughout the event, which helped inspire a framework for generative research results. Additionally, after the event, the team began talking more about how they might find opportunities to listen together, as well as slowing down their process at strategic moments to create more spaces for sense making.

While only researchers were assembled in this case, group combinations could vary depending on the project at hand and its stage of analysis. In fact, this organization had already begun making plans for another Community Listeners event that might include Designers and Product Managers. Other iterations might expand beyond researchers and others who are directly part of the project, to include researchers from outside the project, organizational stakeholders, cross-functional team members, clients, customers, and/or research participants. More fundamentally, the “community” participants would ideally be chosen because they are careful listeners. Community leaders might even consider choosing people from outside their organization—whether fellow ethnographers, or even musicians and sound artists—exactly because the Community Listeners is both a research analysis tool, as well as a training and attunement exercise for the assembled group.

Inspiration for Community Listeners emerged by drawing connections between multiple sources. First, during the course of my research, several professional ethnographers noted the benefit of re-listening to interview recordings, explaining that when they listened again to their own interviews, new subtleties always emerged, adding substance and nuance to ethnographic work. This instinct to listen, again serendipitously overlapped with a legendary origin story of the artist Pauline Oliveros’ listening based practice:

I have been training myself to listen with a very simple meditation since 1953, when my mother gave me a tape recorder for my twenty-first birthday. The tape recorder had just become commercially available and was not as ubiquitous as it is today. I immediately began to record from my apartment window whatever was happening. I noticed that the microphone was picking up sounds that I had not heard while the recording was in progress. After this realization, I gave myself the directive “Listen to everything all the time and remind yourself when you are not listening.” I have been practicing this meditation ever since with more or less success—I still get the reminders after 46 years. My listening continues to evolve as a lifelong practice.

(Oliveros 2010: 75-76)

Similarly, ethnographers should recognize that every instance of listening, again should serve as a reminder to continually return to listening (as our attention continually drifts) and that even brief moments in our data might be a valuable source to continually return to.

The Community Listeners event emerged in conversation with Laith Ulaby, an ethnographer, UX research manager, and ethnomusicologist by training, as we discussed the social nature of listening. Laith was especially fascinated by the communal forms of listening at Jazz Kissa Cafes, sites for collectively focused listening which originated in Japan in the early 20th century. A second source of inspiration we discussed was found in the Tarab musical world—prominent in 19th and early 20th century Aleppo—where a community of expert listeners called the sammīʿah famously attended musical performances to be seen and heard listening by both performers and audiences (Wenz 2016). The sammīʿah, which translates to “those who listen well,” would even be invited to recording studios, thus attuning musicians to the right feel for their music. These concepts of social listening practices helped inspire Community Listeners, an event where “expert” listeners could be placed in conversation with colleagues and other stakeholders.

Soon after the concept took shape, I learned of the Interaction Analysis Laboratory (IAL), a forum for collectively reviewing ethnographic fieldwork videos in multidisciplinary collaborative work groups. IAL was first developed at Michigan State in the 1970s and 1980s, and then brought to the joint venture of the XEROX Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and the Institute for Research on Learning (IRL) in the 1990s (Jordan and Henderson 1995), an important origin site for the development of contemporary professional ethnography (see the Introduction to Cefkin 2010). IAL working sessions were lengthy and in-depth, requiring deep engagement from members of the work group. Diverse teams of researchers and others, potentially including research subjects, were invited to carefully review videos, pausing at moments to provide observations and insights, “whenever anything strikes them as significant” (49). IAL built on the communities of practice work from Lave & Wenger (1991) which understands knowledge, action, and learning as fundamentally social practices:

Thus, expert knowledge and practice are seen not so much as located in the heads of individuals but as situated in the interactions among members of a particular community engaged with the material world.

(Jordan and Henderson 1995: 41)

The social nature of learning applied to both the range of research subjects these groups tackled (i.e. studying communities of practice), as well as the social format of IAL group work.

Collaborative and co-present listening can help develop and train communities of practice. In professional settings, many novice researchers may have never been trained in the finer details of research methods or qualitative analysis. A group listening session can attune them to more advanced or expert ways of listening to research. Alternatively, researchers from different disciplines might share different perspectives and different ways of listening. The forum provides a research team’s leadership with the rare opportunity to guide and train their team in implicit or unspoken ways; teaching by leading, showing, and listening—as well as helping more junior members of the team feel listened to.

As a method that employs listening in novel ways, Community Listeners may also foster greater team cohesion. The event actively attempts to de-center listening practices, repositioning the act of listening from an individual capacity into a group ritual. It creates a forum that allows for a diversity of listening perspectives, exposing researchers to alternative modes of listening, including from different cultural and/or professional contexts. As such, the event aims to facilitate intersubjective relationship-building that fosters understanding of different ways of listening.

CONCLUSION: LISTENING COMMUNITIES

In hearing, the ears take in all the sound waves and particles and deliver them to the audio cortex where the listening takes place. We cannot turn off our ears—the ears are always taking in sound information—but we can turn off our listening. How you’re listening is how you develop a culture, and how a community of people listens is what creates their culture.

Pauline Oliveros (from a 2003 interview with Alan Baker, see Bartley 2016)

One question I asked practitioners in my interviews was: Does the EPIC community have a shared way of listening? Some said they didn’t know and had no way to tell for sure. Others suggested that we don’t, because we come from too many different backgrounds and perspectives. This article points to ways the community might have conversations about listening, create shared spaces for listening, and develop methods for listening. We will not all listen in the same way—and we wouldn’t want to do that, even if it was possible—but what listening experts like Pauline Oliveros teach us is that we can develop shared sites and a common language for how we listen.

For far too long, ethnographers have kept listening to ourselves. That’s perhaps a function of the lack of public discussion about research methods more generally—it is not as exciting to talk about how to conduct an interview, in comparison to talking about what we learned or the implications of our work. When Oliveros states that, “How you’re listening is how you develop a culture, and how a community of people listens is what creates their culture,” she is not solely talking about the internal psychological processes involved in listening. She’s talking about the methods we employ to create space for listening, the forums we have for listening, and the shared contexts we might discover where we can listen, together.

With that in mind, I want to propose that readers take away a series of ideas for listening together. Iterate and make them your own, tailor them to the organizations and/or research projects you work with, and put these ideas to use. Below, I’ll briefly explain some points to keep in mind to do so successfully.

- Highlight listening: Call more explicit attention to listening work already being done in projects, and create more opportunities and occasions for deep listening. These are also opportunities for greater self-reflection about listening practices and perspectives.

- Listen together: Frame listening as a social practice, rather than a purely individual one. Gather a group to listen together and share notes. Social listening is a pathway for fostering communities of practice and an opportunity for ongoing training and development.

- Listen to silenced communities: Prioritize listening to groups, communities, and individuals typically not heard from or who feel like their voices aren’t listened to. This includes underrepresented groups. For product work, it may include non-primary users.

- Listen as a gift: Frame listening as a way to build relationships. Start from a recognition that listening can produce reciprocal relationships and prompt change in both the listener and those who are listened to.

- Listen to attune: In group projects, especially with cross-functional teams that might be tasked with developing research-based insights, use listening to get diverse team members on the same page and orient them. They don’t need to listen the same way, but an entire team can all be ready to listen.

- Listen again, creating recursive loops: We know a first listen changes upon a second listen. The initial experience of listening is fleeting. Use technologies to play back recordings and listen again, revealing what’s been missed, overlooked, forgotten, or undervalued in the first go around. Play back recordings to diverse audiences, and listen to the unique ways these audiences listen. For example, allow research participants to listen to what they said in prior interviews, and allow them to reflect on or even revise their thoughts.

- Listen freely: Approach listening projects as a curator to manage information flows and generate analytical opportunities, rather than the author of insights. Leave space for ongoing listening and analysis.

- Listen wildly: Listening can generate unwieldy sociality, bringing about change that empowers people to do things. What’s unleashed cannot be predicted beforehand. Design accordingly, with specific goals but openness to all potential outcomes.

- Listen differently: Not everyone expresses themselves in the same way or in the same voice. Listening to difference may require different approaches to listening, or greater patience.

- Timely listening: Consider different temporalities of listening, and especially the ways that recording and playback might disrupt traditional notions of time and timely expression. Listen with participants or research colleagues to past recordings. Or use recordings from different places or people to imagine potential futures—or with completely new intention. Longitudinal studies might benefit from playing back recordings of what participants said in the past, allowing them to reflect on and even analyze their own past selves, in order to better understand their personal sense of change.

The above are suggestions, and I look forward to learning about your creative explorations of listening. All I ask in return is that you share what you learn. Listening represents a form of reciprocity, a symbolic exchange between listeners and various sound-producing sources, including people, practices, and environments. That includes fellow researchers and the EPIC community, too.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Powell is a Partner at Practica Group. A cultural anthropologist by training, with a PhD from Rice University, he has been an ethnographic research consultant since 2006. Contact him on LinkedIn or at mpowell@practicagroup.com

NOTES

Special thanks to collaborators and colleagues who helped me develop insights and participated in projects on listening, including Cecilia Balli, Monica Lugo, Laith Ulaby, Hira Qarni, Charley Scull, Gregory Weinstein, Patti Sunderland, Cato Hunt, Dave Dove, Elana Mann, Rita Denny, Jennifer Collier Jennings, and many others in the EPIC community who shared thoughts with me about listening. Special thanks to Natilee Harren for listening to everything all the time and reminding me when I’m not listening. I’m especially grateful for inspiration and guidance from Mike Donovan.

REFERENCES CITED

Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Back, Les. 2007. The Art of Listening. Oxford: Berg

Balli, Cecilia, Michael Powell, and Betsabeth Monica Lugo. 2020. “Real Talk: Understanding Texas Latino Voters Through Meaningful Conversation.” Report for: The Texas Organizing Project Education Fund (TOPEF). Accessed October 9, 2023. https://topedfund.org/realtalk/

Bartley, Wendalyn. 2016. “Pauline Oliveros: May 30, 1932 – November 24, 2016.” the WholeNote. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.thewholenote.com/index.php/newsroom/musical-life/remembering/26402-pauline-oliveros-may-30-1932-november-24-2016

Berendt, Joachim-Ernst. 1985. The Third Ear: On Listening to the World. New York: Henry Holt

Briggs, Charles L. 1986. Learning How To Ask: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the Interview in Social Science Research. Cambridge University Press.

Cardiff, Janet and George Bures Miller. 2023. “Walks.” Artists Website. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://cardiffmiller.com/walks/

Cefkin, Melissa. 2007. “Numbers May Speak Louder than Words, But Is Anyone Listening? The Rhythmscape and Sales Pipeline Management.” 2007 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 188-200. https://www.epicpeople.org/numbers-may-speak-louder-than-words-but-is-anyone-listening-the-rhythmscape-and-sales-pipeline-management/

Cefkin, Melissa, ed. 2010. Ethnography and the Corporate Encounter: Reflections on Research in and of Corporations. New York: Berghahn Books

Cefkin, Melissa and ken anderson. 2007. EPIC Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/conference/epic2007/

Cuciurean-Zapan, Marta. 2017. “Situated: Reconsidering Context in the Creation and Interpretation of Design Fictions.” 2017 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 112-126. https://www.epicpeople.org/situated-reconsidering-context-design-fictions/

Cutler, Grant. 2022. “Silence: Divergent Listening in the Anthropocene.” 2022 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 349-350. https://www.epicpeople.org/silence-divergent-listening-in-the-anthropocene/

Dautcher, Jay and Mike Griffin. 2010. “Ethnography, Storytelling, and the Cartography of Knowledge in a Global Organization: How a Minor Change in Research Design Influenced the Way Our Team Sees, and is Seen by Our Organization.” 2010 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 35-45. https://www.epicpeople.org/ethnography-storytelling-and-the-cartography-of-knowledge-in-a-global-organization-how-a-minor-change-in-research-design-influenced-the-way-our-team-sees-and-is-seen-by-our-organization/

Dove, David. 2016. “The Music Is The Pedagogy.” In Improvisation and Music Education: Beyond the Classroom. Ajay Heble and Mark Laver, editors. Routledge.

Ennis, Ciara. 2018. “Urgency and Echo: Interview with Elana Mann.” Pitzer College Art Galleries. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.elanamann.com/writing/urgency-and-echo-interview-elana-mann-ciara-ennis

Fagundes, Marcelo and Murilo Gomes. 2016. “Tutorial: Structuring Analysis for Innovation.” 2016 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 569-571. https://www.epicpeople.org/structuring-analysis-for-innovation/

Feld, Steven. 1990. Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression (Second Edition). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Forsey, Martin Gerard. 2010. “Ethnography as Participant Listening.” Ethnography 11(4): 558-572

Geertz, Clifford. 1968. Islam Observed. New Haven: Yale University Press

Goren, David. 2022. “Tracing Neighborhoods in the Sky.” 2022 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 346

Gubrium, Jaber F. and James A. Holstein. 2002. “From the Individual Interview to the Interview Society.” In Handbook of Interview Research: Context & Method. Jaber F. Gubrium and James A. Holstein, editors. London: Sage

Gubrium, Jaber F. and James A. Holstein. 2012. “Narrative Practice and the Transformation of Interview Subjectivity.” In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft (Second Edition). Jaber F. Gubrium et al., editors. London: Sage

Hasbrouck, Jay. 2017. Ethnographic Thinking: From Method to Mindset. Routledge.

Hockey, Jenny. 2002. “Interviews as ethnography? Disembodied social interaction in Britain.” In British Subjects: An Anthropology of Britain. Nigel Rapport, editor. Oxford: Berg: 209–222.

Jordan, Brigitte and Austin Henderson. 1995. “Interaction Analysis: Foundations and Practice.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 4 (1): 39-103

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, Pierre and Serena Chao. 2021. “Our ‘New Normal’—The Sensory Landscape.” EPIC People Perspectives. https://www.epicpeople.org/our-new-normal-sensory-landscape/

Lock, Margaret. 2017. “Recovering the Body.” Annual Review of Anthropology v46: 1-14.

Marcus, George. 1995. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1995): 95-117

Marsilli-Vargas, Xochitl. 2022. Genres of Listening: An Ethnography of Psychoanalysis in Buenos Aires. Duke University Press.

Murphy, Kate. 2020. You’re Not Listening: What You’re Missing and Why It Matters. Celadon Books

O’Daniel, Alison, dir. 2023. The Tuba Thieves. Produced by Maya E. Rudolph, Su Kim, Alison O’Daniel, Rachel Nederveld.

Oliveros, Pauline. 1971. Sonic Meditations. Smith Publications American Music

Oliveros, Pauline. 1998. The Roots of the Moment. Drogue Press: New York

Oliveros, Pauline. 2005. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. Deep Listening Publications

Oliveros, Pauline. 2010. Sounding the Margins: Collected Writings, 1992-2009. Edited by Lawton Hall. Deep Listening Publications.

Oliveros, Pauline. 2013. Anthology of Text Scores. Edited by Samuel Golter and Lawton Hall. Deep Listening Publications

Passaro, Joanne. 1997. “‘You can’t take the subway to the field!’: ‘Village’ epistemologies in the global village.” In Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science. Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson, editors. Berkeley: University of California Press: 147–162.

Ratliff, Paul. 2014. “Collateral Revelation”. 2014 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.epicpeople.org/collateral-revelation/

Roberts, Simon. 2020. The Power of Not Thinking: How Our Bodies Learn and Why We Should Trust Them. Blink Publishing.

Rosaldo, Renato. 1993 [1989]. Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press

Schafer, R. Murray. 1994 [1977]. The Soundscape: Our Sonice Environment and the Tuning of the World. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books.

Silverman, David. 1997. Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice. London: Sage

Trimboli, Oscar. 2022. How to Listen: Discover the Hidden Key to Better Communication. Page Two.

Weinstein, Gregory. 2019. “Hearing Through Their Ears: Developing Inclusive Research Methods to Co-Create with Blind Participants.” 2019 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings: 88-104. https://www.epicpeople.org/hearing-through-their-ears-developing-inclusive-research-methods-co-create-blind-participants/

Wenz, Clara. 2016. “Aleppo’s Good Listeners – The Sammi’ah.” The Aleppo Project (website). Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.thealeppoproject.com/aleppos-good-listeners-the-sammiʿah/Winthereik, Brit Ross, Laura Watts, and James Maguire. 2019. “The Energy Walk: Infrastructuring the Imagination.” In digitalSTS: A Field Guide for Science & Technology Studies. Janet Versi and David Ribes, editors. Princeton University Press: pp. 349-364.