Our tiny provocation is that the word “sustainability” is not sustainable. Just using it is sabotaging our efforts to build a better future for the planet. Despite decades of global sustainability discourse, the world is still going to hell. What’s gone wrong? Our paper is about willful ignorance and complicity at a global scale; the benefits of small talk; and a better, more effective word than sustainability.

INTRODUCTION

“Sustainability” is the dream of passing a liveable earth to future generations, human and nonhuman. The term is also used to cover up destructive practices, and this use has become so prevalent that the word most often makes me laugh and cry.’ Anna Tsing (2017, 51)

We (ethnographers working with organisations) recognise the importance of sustainability, defined by Hunter as “treating the world as though we plan to stay” (2020). Some of us work alongside organisations with far-reaching sustainability ambitions. The panel ‘Agency & the Climate Emergency’ at the 2019 EPIC conference asked:

What is the ethnographers’ role in dealing with a catastrophic climate crisis? Should we be exploring people’s experiences of change, trying to use our insights to help drive individual and collective action at scale through organisations, or helping civil society deal with the consequences?

The problem this panel references is sustainability can only be addressed at a global scale, but the complexity of individual practice can only be understood at a human scale. To affect sustainability at scale, organisations need to tap into the practices and beliefs of individuals collectively shaping what’s possible.

We have worked on multiple projects where our clients wanted to understand or communicate sustainability. In 2019 we worked on a global qualitative project at the intersection of sustainability, food and young people. It involved conducting research in six cities and spending time with people, online and in person. The research included market tours curated by local teams to experience how young people in a city buy and eat sustainably. We had conversations with experts in different cities, from academics who specialise in the field of sustainability, to chefs, agency folk who develop different types of communications, packaging specialists, people looking at emerging business models in social innovation and those who lead significant sustainability efforts within global organisations. While we identified valuable insights that addressed specific questions for the client, we ourselves finished in 2019 with more questions than answers.

This paper discusses the questions this project provoked, and covers in detail our 2020 research response. In contrast to the global project with multiple phases and cities, we decided to go small. Our project in Auckland in early 2020 involved eight participants. We asked each participant three questions relating to sustainability, without actually mentioning the word ‘sustainability.’ This approach gained meaningful insights. We will cover three strands emerging from this study. First, we discuss the ongoing presence of silence in sustainability and the slightly provocative question of whether the word ‘sustainability’ is essentially meaningless. Should we continue to use the word ‘sustainability’ if it means so little and is largely empty? Second, we discuss small talk versus big talk and the mismatch between how organisations and individuals talk. What could happen if we bridge that gap? Finally, we turn to the emerging theme of survivability. What does it mean if people are talking survival whilst there is ‘bigger talk’ about sustainability?

WE ALL TALK ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY AS IF IT’S A THING

Field Vignette: 1

I’m sitting in front of my laptop. I’m opening up day 2 on dscout. It’s the first market. There’s the relief in finishing a discussion guide, wrestled over between you, your local team and the client, and then the tension of it landing in the messy lives of humans. Are they the right questions? Are they worded well? Have we connected with people enough? Today people are sharing videos of us of what’s in their fridge and pantry. I start watching. There’s the familiar pleasure in hearing people narrate what they see in their kitchen. At the end of the first video, I notice an awkwardness or silence. We had asked people to finish by showing us the most sustainable item in their fridge or pantry. The person paused. For a long time compared to the last two minutes. “I guess this” as they landed on a bottle of water. I watched other videos. Other people also were silent, hesitant and even reluctant to name anything in their fridge or pantry ‘sustainable’. What made it more intriguing was they had been recruited for behaviours that the client had identified as relevant, sustainable behaviours so as to spend time with people already practising sustainability in some way.

In 2019 we were struck how differently people conceptualise and experience sustainability. People inside organisations and agencies talk as if there is a tangible and universally accepted understanding of sustainability that is actionable at scale through products, policies and practices. The embedded organisational talk (‘sustainable practices’, ‘sustainability creative agency’, ‘making sustainability’, ‘achieving true sustainability’, ‘the influence of sustainability’) assumes a shared understanding. Individuals talk at a human scale across a diverse range of small, personal practices (recycling, plant-based diet, shopping local, workers’ rights) that enable them to feel like they’re doing something “good”.

There appeared to be language gaps. If we introduced sustainability into discussion, yes, people would politely talk about it, and respond to examples provided of possible candidates for sustainable packaging or communications. But people did not talk comfortably, or even consistently, about sustainability. My sustainability is not necessarily another individual’s or organisation’s sustainability. Interpretations could be anchored in economic concerns (viability in business or in wages); social concerns (my family or community); environmental concerns (anything from the degradation of my local environment to global warming); or any elements within the means of production.

Our interviewees struggled to define sustainability and to produce tangible examples in the context of their lives. The Better Futures Report by Colmar Brunton New Zealand (2019) is an annual survey focusing on consumer behaviour towards socially, environmentally and economically responsible brands. The survey found seven out of ten respondents were unable to name a brand leader in sustainability. When asked to pick from a list, sustainability credentials seem to align most closely with overall brand communications and advertising spend. Does this lack of recognition, even after decades of promotion, indicate the word sustainability has limited commercial value and meaning?

The finding contrasted with the experts we spoke to who had roles inside organisations who talked about sustainability as a knowable thing. The experts might allude to the ‘intention action gap’ around sustainability but not that the word ‘sustainability’ has a language problem. We detected a ‘consumer’ silence and also a type of organisational silence. The global brief requested we compile global and market-specific commercial research reports on food, sustainability and millennials for our client. As we spent time with people in different cities, we returned to the commercial reports to see how they framed and managed this language gap. Did they talk about the gaps in language? Trend reports were breathless in their announcement of shifts and changes, including changes in consumer activity in supermarket aisles and social media, but most reported attitude shifts captured in response to statements in surveys. The subheading of the 2018 Nielsen Report The Evolution of the Sustainability Mindset is, tellingly, Get With The Program: Consumers Demand Sustainability’. This trends report claims sustainability has increasing value for consumers but is not translating into consumers discussing sustainability. Can actions and discourse, therefore, be captured by the word ‘sustainability’ anymore?

A global project gives you the time and space to ruminate on significant issues. When we spoke with experts inside organisations, such as the Head of Sustainability at a corporation or university, they were comfortable discussing sustainability. This stood in contrast with ‘regular’ people we interviewed who mostly struggled to talk about sustainability, but what they did talk about was smaller behaviours. There were noticeable silences when we gently questioned organisations’ assumptions about the inherent good and usefulness of sustainability, the language gaps, and what we miss in the present if the brand discourse assumes a particular future (bright, good, optimistic). What are we not discussing? Is sustainability a useful concept-metaphor? Moore (2004) claims concept-metaphors are valuable because they can maintain ambiguity and a productive tension between universal claims and specific historical contexts, as well as acting as a mechanism for all of us to communicate. Is sustainability valuable in this sense? Or is it worthy, but so vague and encompassing so many different associations that it is an essentially meaningless term? Further in her article, Moore cites Appadurai’s use of ‘scape’ as a “space for action and thought not only for anthropologists, but also for… families and individuals.” (2004,79). We have observed that sustainability can be a space for thought for anthropologists (based on books that continue to be published), but little evidence that it is a space for thought for families or individuals. What if “there is no there there” and by introducing sustainability as a topic into conversation we are introducing an artificial construct? We are, in effect, superimposing a concept on the field, rather than understanding how families and individuals might make sense of the conceptual space.

We aren’t, of course, the only people raising issues around the language of sustainability. Hasbrouck and Scull, in Hook to Plate Social Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Approach to Driving Sustainable Change in the Global Fishing Industry comment on the use of the word in the seafood industry:

The imprecision surrounding the definition of “sustainability” has been passed on to consumers, who are largely confused about what it is that “sustainability” means when it comes to fish. “Sustainability,” as a food label term, stands out in its ambiguity even among other ethical food choice labels, whose names are varyingly self-explanatory, such as “free-range,” “shade-grown,” “cruelty free,” and “fair trade.” (2014, 471)

Mike Youngblood uses a textbook definition in his introduction to the Sustainability & Ethnography in Business Series, stating that “Sustainability is an approach to acting in the world in a way that consumes resources and produces waste at a rate that could be continued indefinitely” (2016, 1). If we pause on that definition, what if sustainability as a concept does not connect sufficiently to how people are acting in the world in relation to their consumption or their waste?

What could it mean to work at a human scale? In her chapter ‘Design Ethnography, Public Policy, & Public Services: Rendering Collective Issues Doable & at Human Scale’, Kimbell argues the value of ethnographic practices is:

not that they are human-centred but rather they provide a way to understand sociomaterial assemblages involving complex political, financial, social, and technological systems at human scale…even given limited resources, the analytical orientation of ethnography is productive for asking different questions and provoking new thinking. (2014, 163)

What would it look like to closely attend to human experiences and how people interpret them—to be in the room in a tiny way? What if people did not know that sustainability was on the agenda? What if we let the participants define the challenge—letting the language and concepts emerge from what participants experience and talk about as important and “remain open to what is actually happening” (Glaser 1978, 3)?

At the start of 2020, we recruited eight people across Auckland and spent time with each of them in their homes. (The fieldwork took place between the end of January and the start of February. At the time, COVID-19 was present but unnoticed in New Zealand.) Rather than ask the questions we wanted answers to directly, we let people talk about what they wanted to talk about. Practically, we asked three questions. We asked them to talk a bit about themselves; we explored what was currently on their minds, and finished up with discussing the future. We used listening, probing, and replaying to explore what emerged.

SMALL TALK & LITTLE THINGS VS BIG TALK & GRANDIOSE GESTURES

We learned more about sustainability, both conceptualised and actioned, by asking these eight people in one city three questions unrelated to sustainability than asking a hundred people living in six cities across three continents around fifty questions that were mostly about sustainability. Our exchanges with the former group were of a safe, inconsequential, prosaic kind that happens at the dinner table: “what do you do”, the weather, and how we all know the host. This is small talk. Our exchanges with the latter group concerned the significant, extraordinary and far-reaching type that happen at the boardroom table: what are the biggest issues facing us today, tell me about your sustainable actions, and how about global impact. This is big talk.

We started each conversation by asking them to tell us how they would introduce themselves to someone they just met at a party. At some point, the second question was a version of what’s worrying you, and if something is keeping you awake at night, what would it be? Because we only used these questions, we could relax into the conversation and to give people the experience of being listened to. The conversations had a meandering structure with neither party knowing the direction, structure or even topic.

As people talked about what concerned them, talk often naturally drifted to concerns about the planet. To give this some small, local context: it was the end of the Southern Hemisphere summer. We had all just experienced the sky going an unusual dark orange due to the Australian bushfires, which had disoriented people sufficiently that the police had requested that Aucklanders not ring 111 to report on the condition of the sky. People who wanted to swim or fish at beaches needed to consult different sources of information due to pollution impacting where you could go. At the start of summer, the David Attenborough documentary ‘Our Planet’ had screened. It included a scene where, as a result of a lack of sea ice in the Russian Arctic, hundreds of walruses drag themselves up a cliff and then, unable to get back down, fall to their deaths on the rocks below. The NZ government had banned single-use plastic shopping bags a few months earlier.

Across the eight people, we heard versions of what we now term ‘small talk.’ People specifically mentioned ‘little conversations’ they had had with others. One of our interviewees, Colin, recounted how he and his kids had recently talked about conversations they had when his kids were living at home:

So I talked to my kids and one of the things we always talk about is how we had really good talks in the car, right? They’re like Yeah, we did right you know, we just, well that song sounds pretty cool. I like their way right now. It’s what is this rubbish? And you know, you’d be talking shite, but then you may talk about something else. So I know this boy in my class, likes this song and it’s like, Oh, okay. Right What boy? Yeah, yeah. Okay.

Colin is talking ‘shite’ with his kids but the kids are able through the small talk to talk about the big things in their lives, and Colin is learning about the big things in their lives through the small talk in the car. The fact his kids are now in their twenties, and they remember it, and he remembers it, is quite meaningful. It’s a conversation. Both parties are talking, listening and reacting to the environment they are in. We noticed an opposition between small talk and big talk. Sustainability is an abstract word, mostly used by organisations conveying a big message. We wonder what would have to happen for the large scale monologue and small scale conversations to be joined up.

The business press has promoted ‘purpose’ as a key asset for organisations in the last decade, in particular, drawing upon Sinek’s book Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action (2011) and Stengel’s Grow: How Ideals Power Growth and Profit at the World’s Greatest Companies (2011). This use of sustainability within organisations, alongside a changing climate, provides a context for renewed focus on big ideals articulated as ‘purpose.’ The ESG (environmental, social, and governance) boom in investment (where since 2012, total assets in sustainable investing have more than doubled) has been explained by the publisher Visual Capitalist, who states that:

With a wide range of global sustainability challenges and complex risks on the rise, investors are starting to re-evaluate traditional portfolio approaches. Today, many investors want their money to align with a higher purpose beyond profit. (Visual Capitalist 2020)

Marketing and PR weave sustainability into their reporting, their packaging and statements about new and upcoming products. Oatly released its first sustainability report in 2017, including the statement “Sustainability, that’s what our business is.” as the headline for the lead article in the report, which is an interview with the CEO. This is detailed with:

We are not driven primarily by going to work and earning money. We want to make the world a better place, primarily by contributing something to society, and then making money. But sustainability—that’s what our business is.” (2017, 6)

H&M promotes its Conscious Collection, “Toyota pursues the creation of a sustainable society through its CSR activities”, and BrewDog committed to becoming “the world’s most sustainable drinks company.” And “Unilever has been a purpose-driven company from its origins. Today, our purpose is simple but clear—to make sustainable living commonplace.”

This contrasts with individuals who are reluctant to be the sustainability ‘poster child’. Kerrin, one of our participants, recycles, farms worms, and sews blankets as part of a community group. She is reluctant to be seen as an example of something good, partly from guilt, and her sense of not doing enough.

I guess, in a sense, with the worm farm, obviously, reducing food waste, what’s going into rubbish, things like that. I guess recycling clothes and sometimes I’ll purchase from an op shop [charity shop]. But mostly it’s crockery and just having a knack for old things, I think, yeah, like with my sewing group, we use donated stuff But I guess I personally would not be a spokesperson for it because I’m terrible.

Later in our conversation, Kerrin discusses companies in the fashion industry, in which she works. These companies are discussing their impact on their environment, but from her perspective are still not doing enough as they fly clothing in from other countries.

We could contrast Kerrin with the more angst-ridden Paige, who is torn about her continuation to eat meat. She does other things: walking her child to school, picking up litter, recycling clothes. She sees these little things as being at odds with grand gestures.

No, yeah, I haven’t done any grand gestures. Like I’m aware of all the meat and how much meat industry uses. But I still love meat. So that won’t change. my cousin and friends vegan. Yeah. So we have these discussions a lot. … Just when I see her because you know, what’s worse being aware of, you know, the meat industry and all that stuff, being aware of the effects but still eating meat. Or just you know what I mean? Like, what is worse? Is it worse, but I’m aware, but I still eat meat and I still do this. But it’s just delicious. That’s just my choice at this moment.

Organisations use the term ‘sustainability’ in claims they make, though as noted recently in the FT, “consultants say that most still tend to focus on applying their existing initiatives to conform with the UN’s [sustainability] goals, rather than on reshaping their business models to make them sustainable” (2020). Our participants shared similar scepticism around organisations and sustainability. When discussing the communications team within her organisation tasked with promoting sustainability, Talia said:

I think that’s only because of trends… putting out posters about what you can do to be more sustainable… She’s great at what she does but if she was practiced what she preached she wouldn’t she probably wouldn’t do x y & z …[They are] tapping into the environmental hashtag…we care….

The look on her face, and tone in her voice when mentioning the hashtag, were amplified through finger movements indicating cynicism. Talia described how her organisation publishes posters on sustainability that are put up in key work and public areas as a tick box exercise. We discussed how, once it becomes a communications exercise, it is no longer a real thing.

Our participants noticed the difference between how organisations talked about sustainability and the big things the organisations do to combat climate change. This contrasts with non-organisational small talk. The small things are doable, affordable, and practicable. These make people feel validated about trying their best to make their [local] small world a little better. People are doing small things, but it’s about doing fewer bad things than doing good things per se. Underlying this was guilt and a suspicion that none of this is actually good or making a difference.

BIG TALK IN SMALL CIRCLES, SMALL ACTIONS AS THE LITTLE THINGS ARE IMPORTANT

People talk about doing “little things” by using small talk to talk about bigger issues. This approach is not didactic, not direct, but rather uses oblique, everyday chat and small actions. Kerrin, our young twenty-something who had a worm farm stated:

I guess I might seem a bit odd to some people when this is real big issues out there. I guess I feel like I’m just gonna go and do all these little things. I guess in my view, little things mattered to me, besides just how I was raised, so if I can contribute even in a small way, that makes me feel better.

People exchange within small inner circle(s), talking with and listening to each other. These are genuine conversations. Organisations communicate through monologues. Brands in this space typically talk in big ways, about big things. They broadcast through advertising, packaging and annual reports. People work in their own way to acknowledge the climate is changing. In practice, this looks similar to observing the local effect of climate change; they are no longer able to fish at their local beach. It’s not about the whole world, but their world. It’s talking to their kids about recycling. Emma talked with us about the climate as a wider issue that concerned her, and how recycling was something she was conscientious of. She discussed how her son, 22 years old and sharing a house, he had rung her agitated at his flatmates’ poor recycling practices. She commented:

That’s quite interesting that now I can see all the years of just little conversations I had with them like it has actually filtered through and then it’s quite cool. Things I would have never expected that he would worry about like recycling especially being a young man as well.

People feel safe with immediate family; they lean in with those conversations and integrate small talk and small actions. They try to be encouraging. They take small actions to make themselves feel better or actually just less bad and less guilty. Emma went on to tell us, “you know, if I, if we’re out you know, I’ve got recycling I’ll bring it home I won’t just throw it in a bin while we’re out I’ll bring it home and put it in my recycling. Just a little thing that I feel like I’m doing that’s better.” How we treat each other informs the social and natural environment we live in.

OUR BIG TALK IS IN OUR SMALL CIRCLES; OUTSIDE IS RISKY—WE ARE QUIET

Field Vignette: 2

I’m looking down at my field notes as we debrief in the café. Words like ‘minefield’ and ‘crazy’ had been mentioned by our roofer who had bought an electric car for social encounters. We had recently spent time with a woman who with her husband had set up a business in outdoor meat BBQ. What had emerged was her experience with the ‘angry vegetarian collective,’ people who join a meat BBQ Facebook group or attend a BBQ event just to disrupt and demonstrate. There is a seam of anxieties, emotions and distrust running below the surface, with an observable lack of middle ground on any point of view. This didn’t come up last year in what I would now characterise as earnest or polite discussions. Who else is discussing this? April Jeffries, in her Pecha Kucha at EPIC 2018, discussing middle-class moms in America and the pull toward insular communities. But while Jeffries’ talk explored how hostile or challenging political arguments were increasingly infiltrating conversations, here were more mundane topics such as gardening, food and transport being seen as tricky and dangerous. I go back to the word ‘crazy,’ which has come up with different people, and remind myself how so much of our talk and our behaviours are shaped by our social circles.

A thread through these conversations was the preference for silence in social situations outside intimate groups. Talia’s dad did environmental (what she termed ‘crazy’ behaviours) when she was growing up (for example, cycling to work, saving shower-water for the garden). Now, as a mother in her late twenties, she is revising her opinion about her dad being ‘crazy’:

Probably this weird weather, me and my partner, while we like to fish the last couple years it’s been a little bit of a struggle. So these things directly I think affected me which you know is so selfish and I’m like, this is affecting me. How can I make change happen. Now I care Yeah, but it was like stuff like that.

Not even being. I don’t know if you’re aware, but in Te Atatu. It’s on the beachline. So we locally go out. You know, a lot of the times we’ve gone—we’re not allowed to go fishing. Because of the change in like the sewage which is because of the way the crazy weather, so it’s directly affecting me hmm and that’s when I thought okay, maybe Dad’s not a nutter you know, maybe these people are making some sense. So then I started to ask a few more questions looked at a few more different things and thought, oh wow, this is happening, something is not right.

What is this that is happening?

…I don’t know don’t know if it’s climate change because I still haven’t come to that realisation. There’s something… I don’t know…

What’s the hesitation?

I guess it’s…I should probably do more. If I say it’s climate change I should be doing more.

Talia’s realisation that something is not right derives not from any big idea or organisational intervention but from something small, local, and recent, impacting directly on her life. Yet she couldn’t call it ‘climate change’ because she didn’t know if she was ‘right’ and being ‘wrong’ is a social risk; it’s easier to keep quiet. She also hesitated, because naming it ‘climate change’ meant that she herself would have to do more. But what could she do? What should she do? How would that impact her current way of life? Would it make enough of a difference anyway? She was overwhelmed by both the not knowingness and the scale she faced; it was easier to ignore and be silent in thought and word. We saw this throughout our work: people not talking in or with big groups about big things, and sticking to the safe topics, in our case plastics and recycling, for multiple reasons that can be summed up as ‘Keeping quiet: Don’t let me be the crazy one.’

People actively try to avoid being seen as crazy, fanatical or weird. These words appeared in conversation when people talked about more environmentally-minded family members, or even themselves. In casual conversation, they might phrase their position as “by no means fanatical”. While they talk about their actions as meaningful, they are not discussing them in wider circles because they worry about being seen as crazy. While chatting with one participant, working in the fashion industry, about her worm farms. She told us:

I have a worm farm …if I can contribute even in a small way, that makes me feel better. But then I guess if I, like if I went to a party or a social situation, I may not say I’ve been doing this and this because somebody might say, why would you do that?… Why do all these weird things?

It was important and meaningful to her, but carried enough social risk that she hesitated discussing it in a social situation. People are anxious about what people think of them, and even mentioning having a worm farm or doing something in the house to save water can label you as crazy. Elizabeth Shove (Shove 2010), in presentations on social practices, observes effort is focused on individual attitudes, behaviour, choice price and persuasion. She argues that is the dynamic regimes of everyday life; changing definitions of normal practice generate changing patterns of demand for energy, water, and other resources. Shove states cycling involves “A bicycle, a road, an ability to balance, and the sense that this is a normal and not a crazy thing to do.” In conversation with us, two people dropped their voice when discussing the difficulties of mentioning these topics with wider family, let alone debating them more broadly. Only the topic of recycling seemed to make people more comfortable. (Though, as Aucklanders, we mostly ignore the small signs of no magic recycling fairy making the waste disappear.)

It is not only fear of what people might think of them that causes people to be quiet; there is also the actual experiences people have (or the difference between expected and actual norms). This was described by Colin as a minefield—while trying to combat negative elements in a discussion, he experienced entrenching himself and other people in their position by defending his electric car purchase:

we were lucky enough to have an electric car. So they, not they but a good portion of people, quite like, they want to tear down a new thing right? To come up with you can’t tow with electric car. So well, I don’t want to tow anything. Yeah, you know, I’m not saying you have to get an electric car. I’m just saying that, you know, these are the, these are the positives of an electric car. Oh, he can’t go very far. And there’s always negative negative, negative, negative, negative and I’m like, I try and like combat that but really all I’m doing is just entrenching myself on one side and they’re entrenching on the other side.

This raises the challenge of understanding how new and different ideas enter small talk if people only talk (and listen) to the like-minded. How will new ideas about what we could be doing spread if we are retreating into safe domestic spaces and shouting into an echo-chamber? Colin raised the issue: “Do you work with people that are the same as you, or … with people that are different as you different from you so you can butt heads or you know or are you working with people that are similar so it’s thinking, thinking similar.” How do we break out of our echo-chambers?

KNOWLEDGE: I DON’T KNOW THE RIGHT THING TO DO ABOUT IT

Finally, people are reluctant to talk in wider circles because they are uncertain of what is right, or as Kerrin told us, “I don’t have the knowledge.” This echoed our global project in 2019, where people were unsure of what the right thing to do was. They are no longer learning from verified, independent expert sources but instead from the internet. We also noticed a distrust of established mainstream media organisations who push an agenda that is ‘not me.’ They talked of not watching the news, and referenced Instagram or Netflix. People make sense of what is important to them, using their own sources to find information they want or need to feel like they can make an informed choice. But when they dig into topics (moving from forming opinions based on Instagram likes), they discover issues are not as straightforward as social media portrays. They don’t know what the ‘right’ thing to do actually is; information is now a contested space. In an environment where everything is binary, there is massive social fear of sharing small talk, let alone big talk, that may result in becoming the object of a social media pile-on or ‘cancelled’.

Social media might have been a space for small talk discussion, but it is increasingly tricky due to the social risk of being on the ‘wrong side’ in more polarised discussions. It’s also a performative space. Talia mentioned how her daughter resented the family moving away from meat, but was quick to promote herself on Instagram doing “meatless Mondays.” Kerrin talked of being naughty and tagging someone on Instagram who had promoted recycled coffee cups one day, and then the next day posted an image of drinking a (throwaway) milkshake. Emma, whose husband was involved in the meat BBQ sector, talked of the herd mentality and experiencing “the angry vegetarian collective,” people who join a meat BBQ Facebook group or attend a BBQ event to demonstrate. This sentiment was expressed across different scenarios through increased antagonism and a lack of middle ground on any point of view, with the entire dynamic being one of me/not me, us/not us, vegetarian good/non-vegetarian, pick your binary positions:

I even text my husband. He’s, he’s quite careful because he get you know, like we’ve, we had a situation quite early on when we were talking about barbecue on that Facebook page. And because there’s a lot of Australians on it. And someone addressing something about lamb. And my all my husband wrote was, oh, and New Zealand, lamb as you know, we love lamb and it’s an inexpensive cut of meat, just made a general comment. This guy went through my husband’s Facebook, got to his business page gave him a one star, wrote to him and said how do you like that arsehole. Wow. And had never met my husband and my husband hadn’t said anything particularly specifically to him. Had just made a comment that we live in New Zealand, like lamb, and went against him liking lamb, and now I can’t even get that removed off of Michael’s business page. We’ve tried through Facebook and they won’t remove the one. The ones in there didn’t even know him. He’s not even in New Zealand. You know, it’s interesting the way people’s minds work that they’d make that much effort just because they had a disagreement with you. And I mean, social media. I think Lady Gaga said that social media are the toilets of the internet and it’s so true because there’s so many people that seem to have nothing better to do with their time than to write things to other people that are just so unnecessary.

She and her husband are just trying to make a living. If, even amongst their fellow meat-eaters, stating a fact about lamb in New Zealand can hurt their business, how can you expect to talk about bigger things?

She was also genuinely puzzled why people picket at an event that’s for ‘meat people’. Why yes, her entire family well-being revolves around meat-based BBQs; therefore ‘bad’ based on the plant-based diet sustainability metric. But they also recycle the paper, plastic and food ‘waste’ created by these events; and she grows, consumes and bottles her own fruit and vegetables. Yet there appears to be no time, space or appetite to recognise this level of complexity. There is an increasing us versus them mentality that makes it difficult for people to talk about what they’re doing and why. People are experiencing increasing polarisation—and this interferes with social survival. In contrast, organisations are increasingly pushing messages about a world where diversity is embraced, and inclusivity is the norm (in part motivated by their own social survival), a world that may only exist in marketing and communications.

This has some challenging implications. It is typical to see advice about communicating sustainability and ‘keeping it simple.’ But if people do not feel safe enough to engage in relatively mundane topics, how can these organisations expect people to engage in the big talk around, for example, climate change, or adapt behaviours? Increasingly, positions are held based on populist opinion/reaction, not expert/fact-based information. This contrasts to Ted Talks where we are encouraged to talk about climate change (Hayhoe 2018). But if people do not feel safe enough to engage in relatively mundane topics, how can we expect people to engage in, let alone adapt behaviours for sustainability?

This has implications for scale. One approach might be heading in a similar direction as those working successfully with co-design. They blend the small scale of teams with lived experience with larger experiments. As McKercher (2020) advocates a practice where she recommends to:

typically limit co-design teams to 20 people to prioritise trust, intimacy and social connection. At times, you might have several co-design teams (for example, where people can’t safely be in a room together or where decisions impact millions of people).In small circles, it feels easier to care for and about each other. Small groups are often less intimidating and formal than larger groups. If you’re hesitant, resist falling into the trap of representation—your co-design team cannot be expected to know all things. They focus on depth, while your big circle can focus on breadth. #Tip: Resist the temptation to replace small circles with big groups, shallow consultation and one-off events.

Suchman is quoted in an article called “If You Want to Understand the Big Issues, You Need to Understand the Everyday Practices That Constitute Them” (2019). Her early research looks at how people create meaningful action by improvising:

There is still a tendency to take those for granted, to treat those as if there is nothing to learn about the big issues by looking at mundane practices. And what does it mean to really do that. I think doing that requires a certain kind of access to the worlds that you’re interested in in particular ways that can be quite demanding. To me the aspects of the book that could find their way even more actively into sociological research have to do with that commitment to the idea that if you want to understand the big issues, you need to understand the everyday practices that constitute them. (2019, 32)

These small everyday practices need to be more closely connected to the large scale efforts by sustainability practitioners inside organisations, which may require a different view of ‘bang for buck’ by the organisations purchasing these.

SURVIVAL EVEN MORE IMPORTANT ON A TEMPORAL SCALE—RECONCILING OURSELVES TO A DIFFERENT FUTURE

When we talked to people about the future, they seemed to be reconciling themselves to not only an altered present, such as not being able to fish locally, but also a different future. Our final question used a different format, because we were keen to get people to actively reflect on what they told us and what it meant.

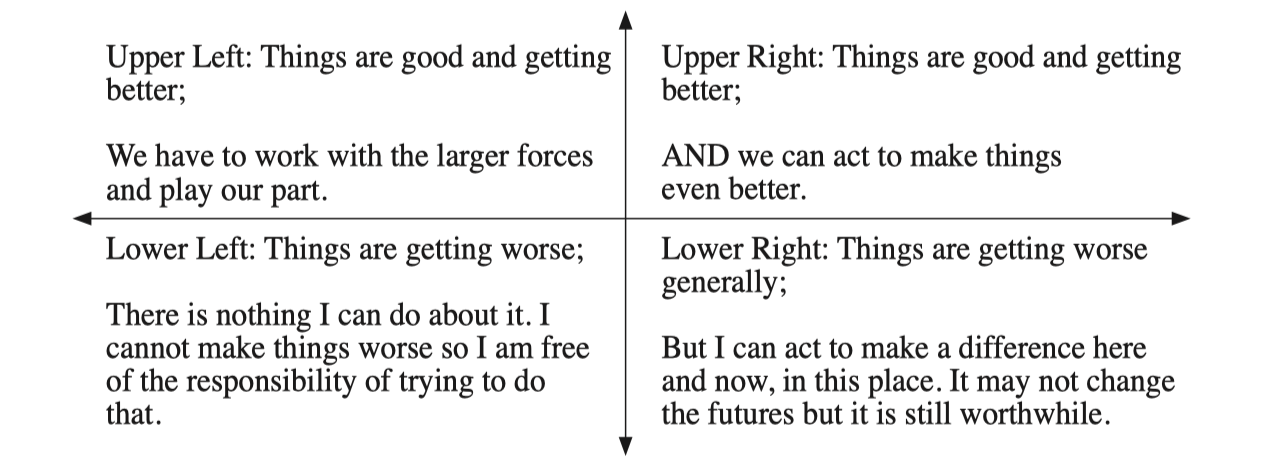

We showed people the four spaces as represented below (Hayward and Candy 2017). Hayward initially developed the grid to explore both how they saw the future (getting better or worse), and their perceptions of their own agency. We asked people, based on their conversation and their experience of the world, which quadrant best captured (or not) where they saw themselves. Did they feel things are getting better or getting worse generally; and what was their perspective of their actions?

© Hayward and Candy, used with permission.

We were interested to see what reaction this provoked in people about the future, and how this functioned as an alternative summing-up method. People wanted to be optimistic. Many of them would start, pause and then restart, saying, “When I first looked at this, I thought I would go with this statement ‘Things are good and getting better”, but as they reflected on the wider context (community, planet), they couldn’t stand by it; as Talia said, “if there is genuine to homeless people living in Te Atatu how can I believe that things are getting better?.” Paige reflected:

I would probably say here. Thanks again, getting worse. But I can actually make a difference here and now. This place might not change your future but it’s still worthwhile. Yeah, that’s a very pessimistic, optimistic, optimistic answer. But I feel I guess I would feel worse if I didn’t do anything like you know, we do little things here and there, but I would makes me feel a little wiggle a smidgen better knowing that I’m trying, you know, trying to do something rather than just doing nothing, but things that I do and they like I said, they are very small.

Paige desperately wanted to be optimistic, but her experiences said otherwise. It’s quite confrontational; self-identifying as ‘not a doom and gloom merchant’, hoping and wanting to part of the solution, and then the realisation of the impossibility of holding this space in a visibly deteriorating world. People are becoming reconciled to a bleak future and apparently experiencing a type of grief. Sometimes labelled ‘felt experience’, or the ‘affect theory’, where people are shaped by narrative, mood or atmosphere. Or as Brown et al. (2019, page) put it, “Our emotions are a response to the way we culturally perceive the world around us.” While people would like to hold onto a belief that “things are getting better”, they are reaching an acknowledgement that things are getting worse.

Do not mistake this as an argument or defence for doing nothing, as this is not the case. It was interesting that our participants claimed to take actions, not because of a big or better future, but because they believed it might make a small difference for their own survival. They can, and will, do their own ‘small’ part even when they know it will not affect anything at a global scale. Neither the present nor the future of the planet seems okay to them. Everyone seemed to agree the future was screwed for those currently at school. Whilst younger respondents felt it more acutely, older participants were concerned future generations will face tough challenges. People grapple with legacy. This translates into the complexities of living in the now with an eye to the impact their action/inaction has on the future for the current generation, without any certainty that their practices are the correct/right ones to make a difference.

We wonder too if there is a difference between people in design roles, or leading futures work, and our participants. Interestingly, on using this activity with different groups, Hayward and Candy (2017, 10) report that “Leaders of various kinds are often well-represented in the UR [upper right] quadrant.” This is the quadrant “things are good and getting better.” Other people who have used this grid as part of their futures work have commented in their blogposts that entrepreneurs also tend towards “The world is getting better and my own efforts directly affect it.”

Optimism and hope are tricky. It can lead to headlines like “Engaging with the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals can help us build a better future post-pandemic.” The use of the term “better future” is intriguing. Are we in a transition? We don’t want to recognise negativity but don’t believe that things will get better. Is it possible if we focus on the small everyday practices, and the zones of small talk; we don’t have to tightly connect actions to big changes. We asked Annie how her younger self would have answered. She told us:

I was totally focused on myself like a 25 year old I’ve talked about. And if we’d asked you then would you say things getting better or things are getting worse? I would have seen probably things are getting better. Yeah. Yeah. Because I needed to believe that….Because I was terribly depressed and not in a good headspace and I had to have something to hold on to. Someone would say to me Everything is getting worse. I’m feeling well, what’s the fucking point and everything’s shitty. I was I would rather have had a comfortable lie than the truth. I was just like, tell me what I want to hear what I want to hear because I don’t want to if it’s not positive and it doesn’t make me feel good and it doesn’t make me feel better about my day, I’m not interested. Don’t be a downer would have been my attitude you.

Turning a blind eye to what is happening is one tactic that people admitted was part of their survival repertoire.

Have We Ended up with Unsustainable Sustainability?

When people hear ‘sustainability,’ they simultaneously hear ‘unsustainability’. We saw that above with Talia and work. At the end of our conversation with Annie, we were interested that the word hadn’t come up given what we had talked about. So, as we were finishing, we asked about the word ‘sustainability’. She frowned, let out a sigh:

I guess in the past, people have talked about. They’ve got these big ideas about and this may be completely wrong. And gosh, I’m really scrambling.

You said you haven’t heard in a while?

Yeah, I thought this has been so off my radar with what’s been going on the last few years …sustainability. Probably a few years ago, people were talking about how to despite the environmental demise and the way the world’s headed, finding ways to keep crops going or keep supply and demand running along well, and you had this big shift in veganism where everyone’s Let’s all go plant based and let’s make vegan meat and so people are either wanting to keep bleeding everything dry forever, or they going let’s find alternative sources now. That’s about the only link I have to sustainability that comes into my mind. I haven’t heard it for a while….

So any of the stuff that you do for example, when you say you’re trying to do your bit, reducing your use of plastics no longer having a bin liner doesn’t fit under sustainability for you?

No, not really.

Psychologists use the term ‘semantic satiation’ for when the repeated use of a word loses any meaning. Like wallpaper, we see it every day but are no longer seeing it.

SURVIVABILITY IS MORE MEANINGFUL

When we started this project, we were interested in what language people might be using. What we didn’t expect to hear as a cross-current through the project was the concept of survivability. We ourselves submitted the initial abstract for this paper with the statement, “Sustainability is the largest scale issue for the planet. Sustainability is a global challenge. It’s important to us as human beings and ethnographers.” When we interrogated this, we realised that not only was ‘sustainability’ not homogeneous to our participants, but also that it did not represent the things that people do to make themselves feel less bad. People don’t use the term ‘sustain’ or raise the question of who gets to sustain what. The conversation was actually about survivability, not sustainability. Participants used ‘survive’ as a verb in contrast to ‘sustainability’ as a vague noun. Surviving is much more tangible and includes getting through life as best as you can. Not just the wherewithal to provide you and yours with shelter, food, water; but also the social intelligence, tools and dexterity to live risk-free in wider society. People had their own ways of coping with what is happening with the planet, including ignoring it. Survival was also framed within the household: “if you’re a family struggling you know to make ends meet, then you’re going to buy what you can.”

We looked around to see if other people were discussing sustainability and survivability. In the introduction to the Extinction Rebellion Handbook, Knights writes, “we acknowledge that Extinction Rebellion is just one articulation of a feeling that is being felt all across the world… To survive it’s going to take everything we’ve got” (2019, 12). Peña-Taylor, on the World Advertising Research Centre website, headlined an article with ‘Sustainability is about survival—the subject needs to overcome the semantic bleaching that makes it a corporate nice-to-have.” He says, “Like the other instances of semantic bleaching that the corporate world is so fantastic at perpetuating (think how ‘undoing structural racism and sexism’ became ‘diversity’), sustainability needs to be more associated with survival than anything cuddly.” Returning to anthropological literature, we came across a chapter on sustainability in the book Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen. It includes a section where a team is trying to learn about the social lives of sustainability (as if sustainability had social lives) in Guatemala and grappling with translating the word sustainability:

We worked together with Marta on the term sustainability for a while—co-laboring, to use Marisol de la Cadena’s (2015) term for a collective effort to attend to spaces of difference. We slowed down when we came across tanquib’ela, which back-translated into el ser en la vida; de vivir; de sobrevivencia, and then, being in life, of living, of survival…The shift between tanquib’ela, mantenerse, surviving, or improving the world is not innocent, but forecloses some worlds while attending to others. The challenge we faced was not only a matter of moving between English, Spanish, or Mam. Whereas a lexicon may elsewhere be units of meanings, the anthropologist’s lexicon might be better conceived as a repertoire of care-filled practices that follow the conversion of spoken concepts into unspoken activities and back into words again. Engaging in the practice of the lexicon requires the skill of asking—and sometimes not asking (see Pigg 2013)—about how words are done and what they then do. (Meza and Yates-Doerr 2020, 465)

We realised that the question of sustainability is in part a linguistic challenge involving the role of words. We were intrigued to discover that “The shift between tanquib’ela, mantenerse, surviving, or improving the world is not innocent, but forecloses some worlds while attending to others” (Meza and Yates-Doerr 2020, 465). In Spanish, and in Guatemala, a team separately arrived at similar discussions. There is a similar level of guilt, sense of loss and acceptance. The passage above highlights “care-filled practices” versus sustainability discourse implying solutions. How might we acknowledge survival, and how does this plays out in a context of small talk?

RECONCILING OURSELVES TO A DIFFERENT FUTURE

Field Vignette: 3

We are trying to rewrite a section of our paper for the umpteenth time. Louisa suddenly says to me, ‘It’s been two years we’ve been working on this and we still can’t say what sustainability means.’ I reply, ‘Your point being?’ We laugh so hard tears appear. We do not know what makes it all so difficult—‘sustainability’ or writing a paper during a global pandemic or something else? We do know that despite decades of global sustainability discourse the world is still going to hell. What’s gone wrong?

We talk about wilful ignorance by us as individuals, us as researchers and us as people working with global organisations. We could stand up and deliver a pretty good talk on sustainability as business as usual. We could easily say brands need to be more concrete in how they relate to community, people are worried about the plastic in the oceans, they feel good about plastic, they say they have the seen the ads with the biggest media spend, and this is what doing good or the future looks like. It’s conventional big talk. This misses what we have learned through the small talk. What follows is some tentative stuff, and questions we are left with…

After two years of large and small projects on sustainability, what have we learned? What would we tell people we work with who are keen to know not only the ‘what’, but also the ‘so what’ and ‘now what’?

Our Own Unsustainable Use of Language

The initial challenge we discovered with sustainability was that the concept lacked clarity. There were so many different meanings associated with the word it became essentially meaningless. We also learned that the word is overused. People not responsible for sustainability as part of their role in an organisation or group are cynical about its use due to what they see on social media and their experience with organisations. Further, the use of ‘sustainability’ is possibly as unsustainable as the way we are living—it is not getting us closer to providing a solution to the problems we face. Which raises a catalytic question: why do we ignore this? Why are we complicit in maintaining a social silence?

Currently ‘Sustainability’ Acts as a Cipher

Sustainability appears to operate as a code word, and that social silences continue to exist inside organisations. Gillian Tett discussed such “social silences” in The silo effect: why putting everything in its place isn’t such a bright idea (Tett 2015, 45):

what really matters in a society’s mental map is not simply what is publicly and overtly stated, but what is not discussed. Social silences matter. The system ends up being propped up because it seems natural to leave certain topics ignored, since these issues have become labeled as dull, taboo, obvious, or impolite. …as Bourdieu said: “The most powerful forms of ideological effect are those which need no words, but merely a complicitous silence.

Tett has described the social silence of people operating within the wider financial field around the explosion of derivatives in the financial markets, which led in part to the financial crisis back in 2009. We wondered: is sustainability a social silence? Why do organisations continue to communicate sustainability, even while knowing that the word is problematic? If people inside organisations name what an organisation does as ‘sustainability,’ this is a form of power or as Bourdieu would term it, a use of symbolic capital. This use of language within organisations leads to Annie and Talia being disillusioned with ‘sustainability’ as they notice that its primary use is not for them but for the users of that language to claim a particular status.

Practically, sustainability appears to now operate as a cipher—you only access value by knowing how to use the code. The word ‘cipher’ has an Arabic root. Sifr; zero, empty, nothing. When a word like ‘sustainability’ is used so broadly, it becomes an empty signifier. Holly Jean Buck – Assistant Professor of Environment and Sustainability University at Buffalo in New York – discussed this when participating in an online conversation at Assembly 2020. She was invited along with others because her specialist work embodies long term thought to discuss the future. When asked about the political ways in which a word is used, she was specifically asked:

in the vernacular of your field, what words, what phrases what terms have become bastardised, have become overcomplicated oversimplified so they have no meaning and now their meanings have been galloped away with?

She replied: “Sustainability- it’s become empty of content….it’s become a corporate term, it’s a work phrase now”(2020, 8:10:12). The in-group is less concerned that the word lacks concrete meaning, as it performs its function as code for funding, measures or proof of corporate citizenry etc. Restricted codes have always been used. Sentries and doorkeepers may only allow someone to pass if they know the code. Thus, codes operate as secret signals or ‘badges of belonging’. Sustainability and its derivatives sometimes operate as such a code where you need to decipher intention and appropriate behaviours. No longer do people need a special word to gain physical entry; they need the appropriate language to be considered a legitimate ‘player’ for funding, recognition, or inclusion for their own survival. Hence we see the use of vague phrases such as ‘business sustainability review,’ or ‘sustainable economic growth.’ Others see the word, with limited understanding or appreciation of its intended meaning or purpose, and use it to say: “I’m a part of this club too.” The word loses legitimacy or potency through inappropriate use.

How about a different word? As a candidate, how about ‘survivability’ as a more representative word capturing how real people are thinking, talking and acting? We are hard-wired to survive. Looking across the vast temporal scale of human existence, since our ancestors first crawled out of the sea, we humans have continually adopted and adapted the actions and behaviours required to survive. Let’s not forget that organisations are driven to survive also, taking on board the policies, practices and publicity that keeps them viable. It’s survival of the fittest, not sustainability of the fittest.

If You’re Trying to Talk to People about Sustainability, You Can’t Talk about Sustainability

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted in the UN General Assembly in 2015 and has primarily been picked up by governments and businesses, either for action or justification. In May 2018, during a UNEP/OECD event on sustainable lifestyles, Townsend, of Futerra, developed a version of the UN Sustainable Development Goals to make them more tangible. An example is instead of “reduced inequalities” she used “Be fair, ” instead of “Sustainable Cities and communities” she used “Love where you live.” They were intended to be clearer and more engaging than the original goals and proved popular when she shared them on social media. After some copyright issues following a tweet, there was a collaboration between Futerra and the UN resulting in “The Good Life Goals”, which were launched at the UN headquarters in 2018 focused on “bridging the gap”. What is the gap? Futerra characterises this gap on their own website as a language gap. “The world’s governments, civil society, stakeholders and business did a pretty good job of creating a To Do List for humanity. Except that list is written in a way which excludes the most important change-maker of all—YOU.” The Good Life Goals do not mention sustainability and are characterised by concrete and specific language. Examples of the rewritten goals are below: (Futerra, 2020)

The criteria for rewriting the goals included:

- Will this personal action make a tangible impact on the Goal?

- Will this action be accessible/relevant/affordable to the greatest number of people?

- Is the action comprehensible and likely to benefit our own lives? (Futerra, 2018)

The reworked goals are much closer to the social practices of our participants – small, attainable, tangible and socially acceptable rather than increasing their risk of being a target at the next social gathering. Further, they are an example of what Townsend believes that “I personally believe that people power is as important as powerful people.” She and her team are actively bridging the gap between people and very large organisations, such as the United Nations.

Holding the Space Between an Optimistic and Pessimistic View of the Future

People inside organisations tend to use ‘sustainability’ in an optimistic way. As described by Meza and Yates-Doerr:

Sustainability (and, we might add, becoming and emerging, since these terms often go hand-in-hand) may too easily connote the progressive transition of a singular, causal system, leading us toward the project of developing a better future that has long been modernity’s destructive lure (2020, 465).

Hayward’s phrase that we used “Things are getting worse generally… but I can act to make a difference here and now, in this place” is close to what people are telling us about their experience. “It may not change the future, but it is still worthwhile.” It turns out people don’t have to feel that they can make a difference to the world to act in the here and now. Remember that our participants claimed to take actions, not because of a big or better future, but because they believed it might make a small difference for their own survival. It might help their physical survival, probably their social survival, and at the least will make them feel better about themselves. They can, and will, do their own ‘small’ part even when they know it will not affect anything at a global scale. How do we design new products and services and communicate these in a world where people want to be optimistic, but can’t? If we accept ethnographers have always been engaged in the language of loss (Behar 2003), then some of the answers and questions will lie in our own practice.

EMBRACING THE SMALL TALK ABOUT SMALL THINGS

Bronislaw Malinowski introduced the term ‘phatic communion’, verbal or non-verbal communication that has a social function, nearly a century ago in his essay “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages” (1923). We found that small talk is more than just chit chat; it’s a way of navigating massive issues. Start where people are at; small and concrete. Our brains struggle to hold the complexity of the large scale; we naturally gravitate to the small scale of the local.

We notice how much emotion and subjectivity are caught up in people’s reactions and behaviours. We contend that, in some pivotal way, sustainability comes between us and our relationship with our environments. The OED identifies the primary meaning of sustainability, and the verb ‘sustain’ as ‘to keep in existence, maintain; spec. to cause to continue in a certain state for an extended period or without interruption.” Our participants know, without being able to articulate this, that the current way of living is unable in some way to continue. Survivability has more in common with an obsolete form of ‘sustain’’ which derives from Old French sostenir, meaning “hold up bear; suffer, endure.”

While the people we spoke to are adjusting to the signals of a darker future, they themselves see both meaning and hope in both their small talk and their actions. Small talk may be about intimate and small scale things, but in fact, it is important on a human level and is probably also pretty widespread. There’s a political choice not to use what has become bureaucratic, abstract big talk, but rather to lean closer to both worlds and the conversations that people are having in their own local situations. We wonder about the implications for action. We have learned we need to embrace the mundanity of the small talk if we don’t want to sabotage our survival.

Louisa Wood is happiest immersed in unravelling the human experiences of others. Her foundation in theatre and semiotic thinking provides a different attentiveness to the framing of these, while a career in qualitative research provides a space in which to do so.

Lee Ryan completed an MA Hons at the University of Auckland then another at UCL. She was the Regional Director for Qualitative Research at TNS for Asia Pacific, Latin America, Middle East & Africa. Back in Aotearoa, she aims to write more things long-form after writing 4125 PowerPoint slides.

NOTES

Thanks to everyone who helped us to both understand and communicate more clearly what is happening – Viv McWaters, Johnnie Moore, Bren Simson, Kathryn Spencer, ArclightTV, Erin Taylor (we think we scored the best editor at Epic 2020 – smart, patient, thoughtful). But we want to thank all the people who invited us into their homes where we spent long summer afternoons in conversation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Auckland, Emily. 2020. “Engaging with the SDGs can help us build a better future post-pandemic.” Edie website, May 4. Accessed [September 1, 2020] https://www.edie.net/blog/Engaging-with-the-SDGs-can-help-us-build-a-better-future-post-pandemic/6098765

Behar, Ruth. 2003. “Ethnography and the Book that was Lost,” Ethnography 4 (1): 15-39.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1994b. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

Brown, Steven D, Kanyeredzi, Ava, McGrath, Laura, and Ian Tucker. 2019. “Affect theory and the concept of atmosphere.” Distinktion 20 (1): 5–24.

Buck, Holly Jean. 2020. “Longplayer Assembly.” Artangel website, 2020. Accessed [September 27, 2020]. https://www.artangel.org.uk/longplayer/longplayer-assembly/8:10:12

Colmar Brunton. 2019. “Better Futures: Celebrating a decade of tracking New Zealanders’ attitudes & behaviours around sustainability.” Colmar Brunton website, 2019. Accessed [September 7, 2020]. https://static.colmarbrunton.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Colmar-Brunton-Better-Futures-2019-MASTER-FINAL-REPORT.pdf

Futerra. n.d. “Why We Need New ‘Good Life’ Goals.” Futerra website, 2020. Accessed [September 1, 2020]. https://www.wearefuterra.com/2018/07/why-we-need-new-good-life-goals/

Galik, Gyorgyi. 2019. “The Change Before Behaviour: Closing the value-action gap using a digital social companion.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, 2019: 415-439.

Ghosh, Iman. 2020. “Visualizing the Global Rise of Sustainable Investing.” Visual Capitalist website, February 4. Accessed [September 1, 2020]. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/rise-of-sustainable-investing/

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Hasbrouck Jay, and Charlie Scull. 2014. “Hook to Plate Social Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Approach to Driving Sustainable Change in the Global Fishing Industry.” In: Handbook of Anthropology in Business, edited by Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland, 186-201. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Hayhoe, Katharine. 2018. “The most important thing you can do to fight climate change: talk about it.” TED website, November 2018. Accessed [September 1, 2020]. https://www.ted.com/talks/katharine_hayhoe_the_most_important_thing_you_can_do_to_fight_climate_change_talk_about_it

Hayward, Peter, and Stuart Candy. 2017. “The Polak Game, or: Where do you stand?” Journal of Futures Studies, 22 (2): 5-14.

Hunter, Laura. n.d. “Laura Hunter.” Intent website, 2020. Accessed [September 30, 2020] https://www.intentjournal.com/features/laura-hunter/

Inagaki, Kana. 2020. “UN sustainability goals set standard for Japanese businesses.” Financial Times website, July 23, 2020. Accessed [September 1, 2020]. https://www.ft.com/content/89711e3c-afeb-11ea-94fc-9a676a727e5a

Kaplan, Josh. 2017. “When the Emperor Has No Clothes: Performance, Complicity and Constraints on Communication in Corporate Attempts at Innovation.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, 2017: 217-231.

Kimbell, Lucy. 2014. “Design Ethnography, Public Policy, & Public Services: Rendering Collective Issues Doable & at Human Scale.” In Handbook of Anthropology in Business, edited by Rita Denny and Patricia Sunderland, 186-201. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Maldonado García, María, García Meza, Rosario, and Emily Yates-Doerr. 2020. “Sustainability.” In Anthropocene Unseen: A Lexicon, edited by Howe Cymene and Pandian Anand, 465-469. Earth, Milky Way: Punctum Books.

Malinowski, Bronislaw (1923) The problem of meaning in primitive languages. In C.K. Ogden & A.I. Richards, The Meaning of Meaning, Supplement I. London: Kegan Paul, pp. 451-510.

McKercher, Kelly Ann. 2020. Beyond Sticky Notes: Doing Co-design for Real: Mindsets, methods and movements. Sydney, Australia: Beyond Sticky Notes.

McGonigal, Jane and Mark Frauenfelder. 2016. “Futurist Imagination Retreat Report.” University of Pennsylvania website, May, 2016. Accessed [September 1, 2020] https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/web.sas.upenn.edu/dist/8/471/files/2018/06/Futurist_Imagination_Retreat_Report-2fge730.pdf

Moore, Henrietta L. 2004. “Global anxieties: concept-metaphors and pre-theoretical commitments in anthropology.” Anthropological Theory 4 (1): 71-88.

Nielsen. 2018. “The education of the sustainable mindset.” Nielsen website, 2018. Accessed [7 September 2020]. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2018/the-education-of-the-sustainable-mindset/

Oatley. 2018. “Sustainability Report 2017.” Oatly website, October. Accessed [September 4, 2020] https://www.oatly.com/uploads/attachments/cjp9gpbd709c3mnqr8idyecwy-sustainability-report-2017-eng.pdf

Shove, Elizabeth. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: How social science can help climate change policy.” SlidePlayer website, n.d. Accessed [September 27, 2020]. https://slideplayer.com/slide/1658232/

Suchman, Lucy, Gerst, Dominik, and Hannes Krämer. 2019. “’If you want to understand the big issues, you need to understand the everyday practices that constitute them.’ Lucy Suchman in conversation with Dominik Gerst & Hannes Krämer.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [Online] 20 (2). Accessed [September 1, 2020]. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.3252

Tett, Gillian. 2015. The silo effect: why putting everything in its place isn’t such a bright idea. London, U.K.: Little, Brown.

Townsend, Solitaire. 2018. “An approach to making the SDGs personal.” GreenBiz website, October 4. Accessed [September 1, 2020]. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/approach-making-sdgs-personal

Toyota. 2020. “Sustainability.” Toyota website, 2020. Accessed [September 4, 2020]. https://global.toyota/en/sustainability/

Tsing, Anna, 2017. “A Threat to Holocene Resurgence is a Threat to Livability.” In The Anthropology of Sustainability: Beyond Development and Progress, edited by M. Brightman and J. Lewis, 51-66. Volume in Palgrave Studies in the Anthropology of Sustainability. New York: Palgrave.

Van der Linden, Sander, Maibach, Edward and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2015 “How to Improve Public Engagement with Climate Change: Five “Best Practice” Insights from Psychological Science”. Perspectives on Psychological Science [Online] 10 (6): 758-763. Accessed [September 7, 2020]. https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/slinden/files/ppsfinal.pdf

Youngblood, Mike. 2016. “Sustainability and Ethnography in Business: Identifying Opportunity in Troubled Times.” EPIC Perspectives, December 5. Accessed [September 4, 2020]. https://www.epicpeople.org/sustainability-ethnography/