The People Say is a pioneering research repository and a model for making rich qualitative data available for policy innovation. This case study describes the rigorous research and data processing techniques used to create the platform, as well as the immediate impact it had in informing policy. It addresses a key challenge for government agencies and NGOs, which increasingly involve the public in formative research, yet face limitations around recruitment, lack of longitudinal studies, and poor engagement policies. Created by Public Policy Lab and SCAN Foundation, the platform is designed to improve policymaking for older adults, with 108 topic and subtopic tags that users can use to filter and associate data with existing quantitative studies. The project also underscores the value of qualitative research in capturing lived experiences and shifting systems to meet the needs of marginalized populations. Future goals include longitudinal research, expanding to other demographics and locations, and supporting civic researchers in creating more public research.

Introduction

Today, government agencies and NGOs are increasingly engaging in formative research with the public. At minimum, they seek to validate digital products before launch. More ambitiously, some attempt to engage the public in the co-design of policy and service delivery.

However, current practice has multiple major limitations:

- recruiting diverse humans is time-consuming and often fails to meet inclusion goals;

- research is typically one-off, rather than meaningfully longitudinal and contextual, producing shallow findings;

- public-sector entities have weak (or actively unethical) policies and practices for engagement, particularly relating to compensation, consent, and participant confidentiality;

- research findings are treated as proprietary, causing different agencies and organizations to re-study the same issues and communities, wasting resources and undermining public trust;

- members of the public have limited or no visibility into how their personal data is used, creating cynicism about engagement efforts; and,

- ultimately, the research process extracts value from (often marginalized) people while reserving all real interpretive and decision-making authority to high-power actors, undermining democratic ideals.

In an effort to respond to these issues, the authors’ organization, the Public Policy Lab, formed a partnership in 2023 with The SCAN Foundation. The Public Policy Lab (PPL) is a nonprofit organization with a mission to design policy and services that help Americans build better lives. The SCAN Foundation (TSF) is an independent public charity devoted to transforming care for older adults to ensure all of us can age well with purpose.

Together, we committed to conducting a research project and subsequent creation of a public data platform to catalyze human-centered policymaking around the health and wellbeing of older adults. That platform, The People Say (https://thepeoplesay.org/), launched in July 2024. This case study describes the goals of the project, the activities we conducted to develop the platform, the lessons learned conducting the work, and the next steps for the development of the project – and for the field of civic design research.

Project Context and Goals

Current Challenges

Health and aging policies and systems are designed to respond to the needs of system power-holders, rather than that of citizens and consumers. There is a need to elevate what members of the public actually want, if government policies and healthcare-delivery systems are to reflect their needs – and generate awareness and competition among regulators, providers, and payers to respond to those needs.

When advocates, policymakers, and providers do seek to learn from older adults, those engagements often have significant limitations:

Existing Datasets and Surveys Do Not Adequately Focus on Priority Populations

When current research refers to older adults, particularly people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, it often describes this population being heterogeneous – but it doesn’t break down the real differences among populations. Research often fails to prioritize marginalized or vulnerable people and tailor research questions and activities to those populations – even though marginalized populations are most at risk of harm if policy fails to account for their needs.

While there’s a growing interest in developing ‘people-centered’ systems and policies, government is ill-equipped to conduct this research, leaving a knowledge gap that needs to be filled. Further, government systems are often set up only to deliver either universal services or ones that have been customized to individual needs, often after burdensome appeals or litigation processes. If major themes related to the needs of different populations can be identified, policy stakeholders can develop ‘flavors’ of policy that speak to different community or life situations, rather than grappling with individualized services (which can be perceived as unachievable and expensive).

Existing Datasets and Surveys Do Not Adequately Capture the Lived Experiences of Older Adults

In addition, policy recommendations often rely solely on survey and claims data, and stakeholders can generally find refuting data points. A more effective approach is to couple survey and claims data with human-centered design, to not only capture what people experience, but also why and how they feel about their experiences.

However, currently, human-centered research efforts are often structured as one-time activities, even though health access and delivery are experienced as a series of touchpoints over time – leading to limited understanding of how people’s requirements evolve as their health, financial, housing, and other personal circumstances change over the decades after they turn 65. If stakeholders can be presented with compelling narratives that illuminate the real needs of older adults- and importantly – how those needs evolve over time – they may be more likely to take action.

Existing Datasets and Surveys Do Not Adequately Address the Urgent Need to Engage in System and Policy Changes Now

America’s population is aging rapidly, and neither our healthcare systems nor our social policy is responding with appropriate urgency. Millions of baby boomers are already turning 65, and their children and grandchildren – or ill-prepared safety-net services – are shouldering their care, with poor outcomes for both older adults and society at large. One reason for the lack of urgent action (among many) is that the insights gathered from existing research with older adults often remain siloed within commissioning organizations and agencies, rather than being disseminated to a coalition of engaged stakeholders as compelling data to inform policymaking and healthcare innovation nationwide.

By developing the right kind of public data, from the highest priority populations, while building a coalition of committed partners to use that data, The People Say hopes to shift the conversation on what needs to be done to build a society that works for older adults, their families, and all of us.

Project Components

To address the problems above, we formed a pool of older adults engaged with The People Say for ongoing human-centered research. We developed qualitative data on their preferences and experiences, then launched the platform – designed for use by advocates, policymakers and other stakeholders – to highlight actionable findings and insights about older adults’ health and wellbeing needs.

Specifically, we’ve created:

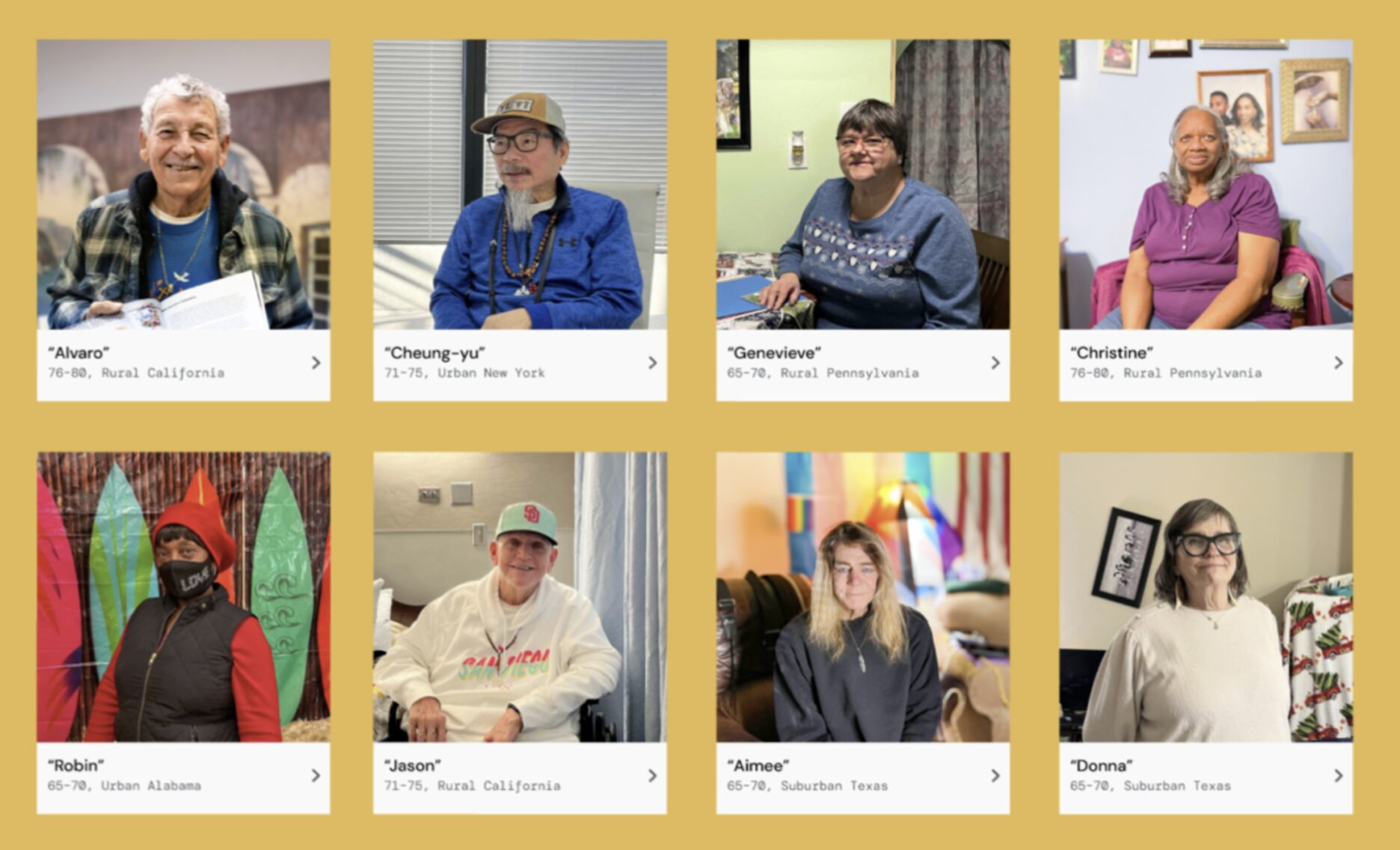

- A research pool of older adults – representative of all older Americans, but over-sampled on marginalized populations – with the intention and related infrastructure to be able to return to that pool regularly over time, both to conduct follow-on research related to this project and to address other specific research questions;

Fig. 1. Profile photos of eight members of the research pool. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

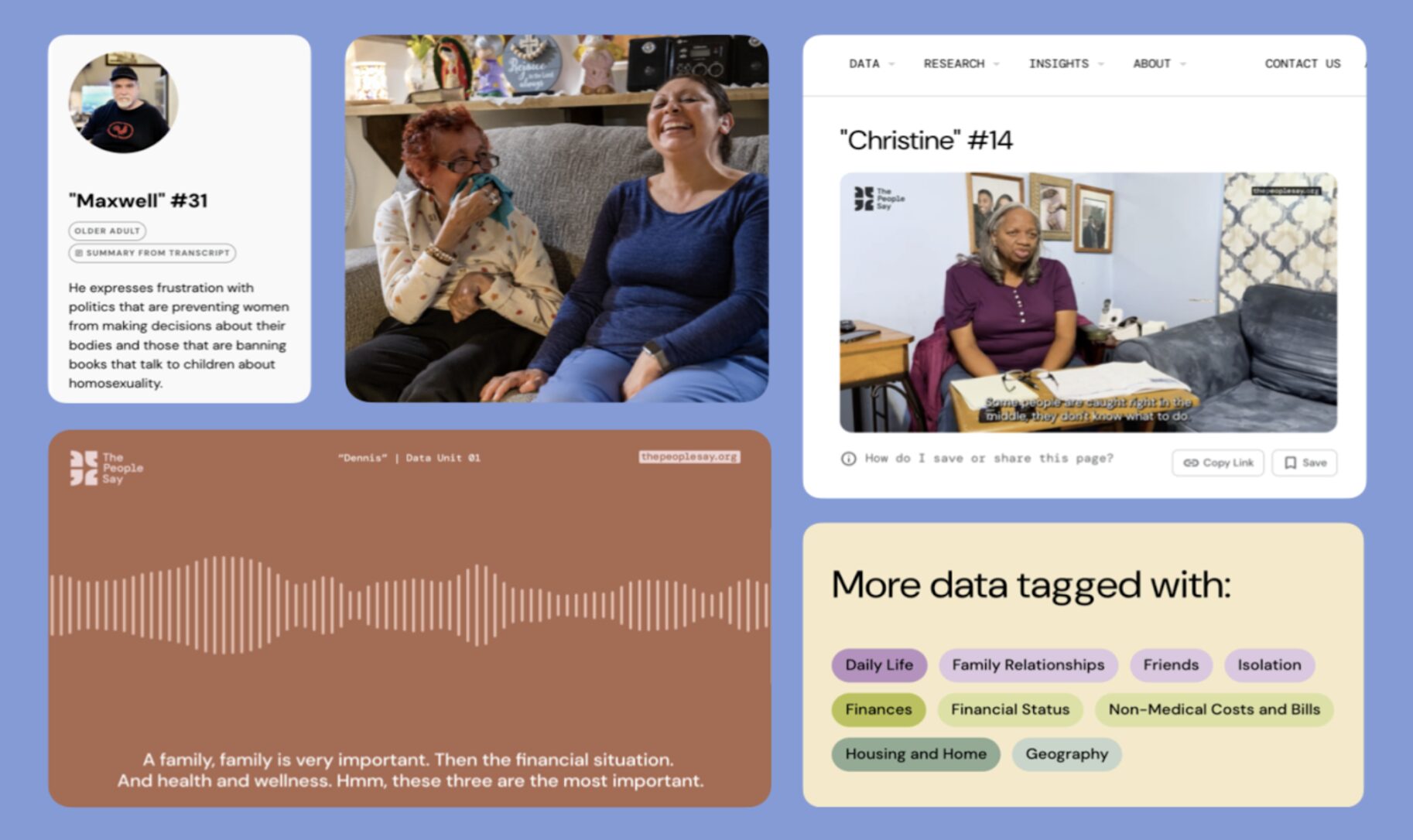

- A repository of tagged research data, includingboth synthesized insights from research and direct quotes, transcripts, photographs, audio and video recordings, and other artifacts from research created by members of the pool of older adults, all categorized per a taxonomy developed by the research team; and

Fig. 2. An array of different types of qualitative data hosted on The People Say. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

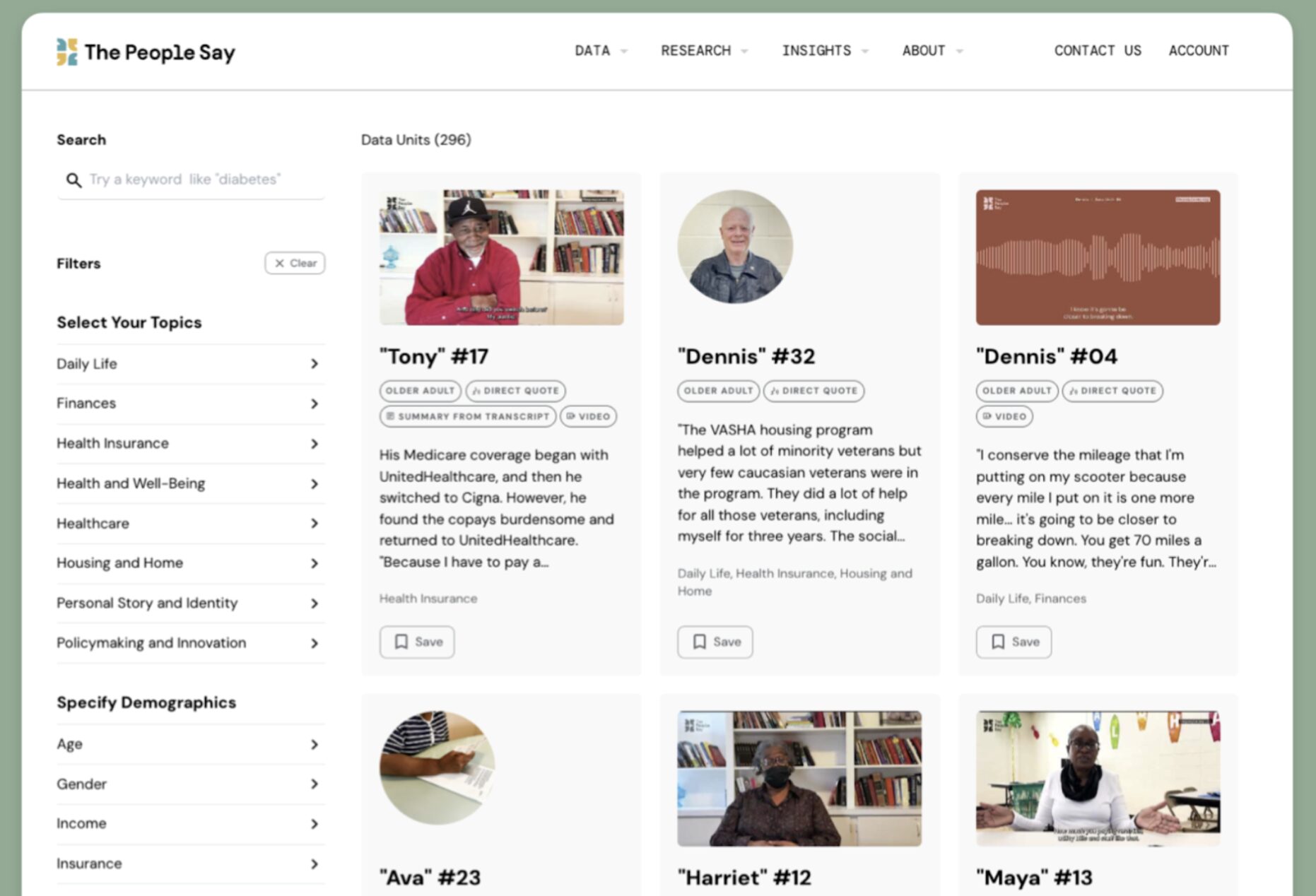

- The People Say,an online platform that publicly shares out findings and insights generated with those older adults regarding their healthcare access and delivery experiences, designed to highlight opportunities for national policy change and nationwide healthcare-systems improvement.

Fig. 3. A screenshot of the search page for The People Say. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Project Goals

The overarching goal of The People Say is to support the development of policies, systems, and programs that are more reflective of the needs and preferences of older adults. In support of that goal, in the first year post-launch, we expect the project will have three short-term outcomes for project stakeholders:

More Meaningful Input from Older Adults

Creation of the standing research pool will reduce recruiting and outreach difficulty, allowing PPL, The SCAN Foundation, and partner organizations to more frequently and rapidly seek older adults’ input and/or participation in goal-setting and decision-making. (Even before formal platform launch in July 2024, this goal began to come to fruition: PPL and TSF are using the research infrastructure to support the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Community Living in engaging with older adults to inform the creation of the decennial national Framework on Aging.)

Thicker Data Analysis and Storytelling

Development of the research repository will allow users of The People Say to better identify older adults’ needs and preferences over time (as opposed to single-point analysis) and to convey that analysis in more human and compelling ways, given the easy availability of rich visual and audio assets associated with data points.

Broader Reach and Influence

Launch of The People Say will create new opportunities to advocate urgently for improvement in policies and services for older adults and to push for policy change that responds to older adults’ lived experiences/needs as well as broader social-change goals. Project outputs may also be adopted by service providers, payers, and other stakeholders to contribute to momentum and evidence for larger policy change.

Project Activities

We conducted the project through six phases of work, from initial scoping and preparing, to research and synthesis, and then to co-design and launch. The project took just short of a year, from kick-off in September 2023 to public launch in July 2024. Activities undertaken over the course of the project are described below.

Preparing for Research

Sample Size

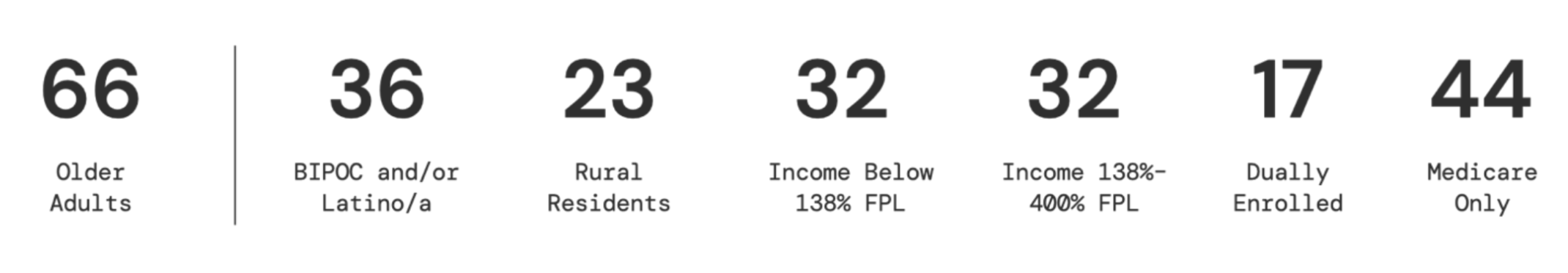

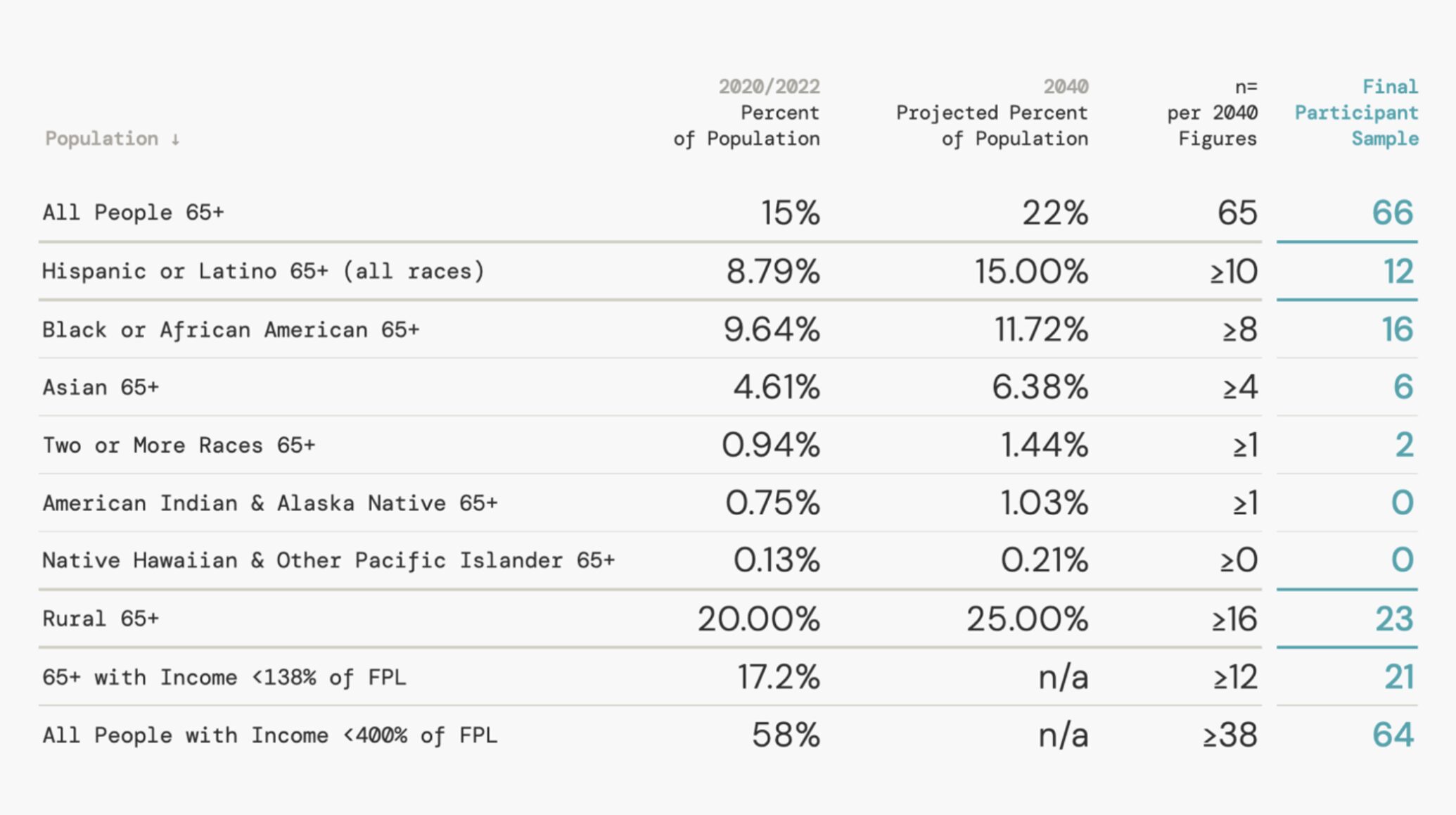

We planned a sample of 65 older adults, in a nod to the estimated population of 65 million Americans over the age of 65 in 2025. Ultimately, we engaged 66 older-adult participants, along with seven caregivers and 13 subject-matter experts, for a total of 86 participants.

Fig. 4. Our 66 older-adult participants represent multiple racial/ethnic backgrounds, income groups, and geographies. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Sample Selection

When initially setting recruiting targets for our sample, we started by identifying a baseline distribution of gender, racial/ethnic, geographic (urban/suburban vs. rural), and income demographics that mirrors the current 65+ population. Beyond seeking to highlight lives and aspirations of all older Americans, however, the Public Policy Lab and The SCAN Foundation share a commitment to focusing on the life experiences, needs, and preferences of populations that experience health disparities – particularly people of color, low-income people, and people who live in rural, medically underserved areas.

To deepen our research on these populations, we decided to oversample for participants who had those backgrounds or characteristics, with the aim of hitting levels equal or greater to the projections of the demographics of America in 2040. That forward-looking focus allows our participant pool to speak to the more diverse future that America is aging into, serving project interests in developing policy now that addresses the needs of the next 15 to 20 years.

See below for current (2020) demographics versus projected 2040 demographics, as well as the target and actual number of participants we recruited, reflective of those different distributions. Note that the racial/ethnic categories in the table below (and the terms used) are drawn from U.S. Census materials.

While a number of our respondents indicated that they were of Indigenous descent, none are enrolled members of a sovereign Tribal nation. In all other instances, we exceeded our targets for engaging lower-income, BIPOC, and rural participants.

Fig. 5. Starting with projections of the 2040 65+ population, we then oversampled for priority populations. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

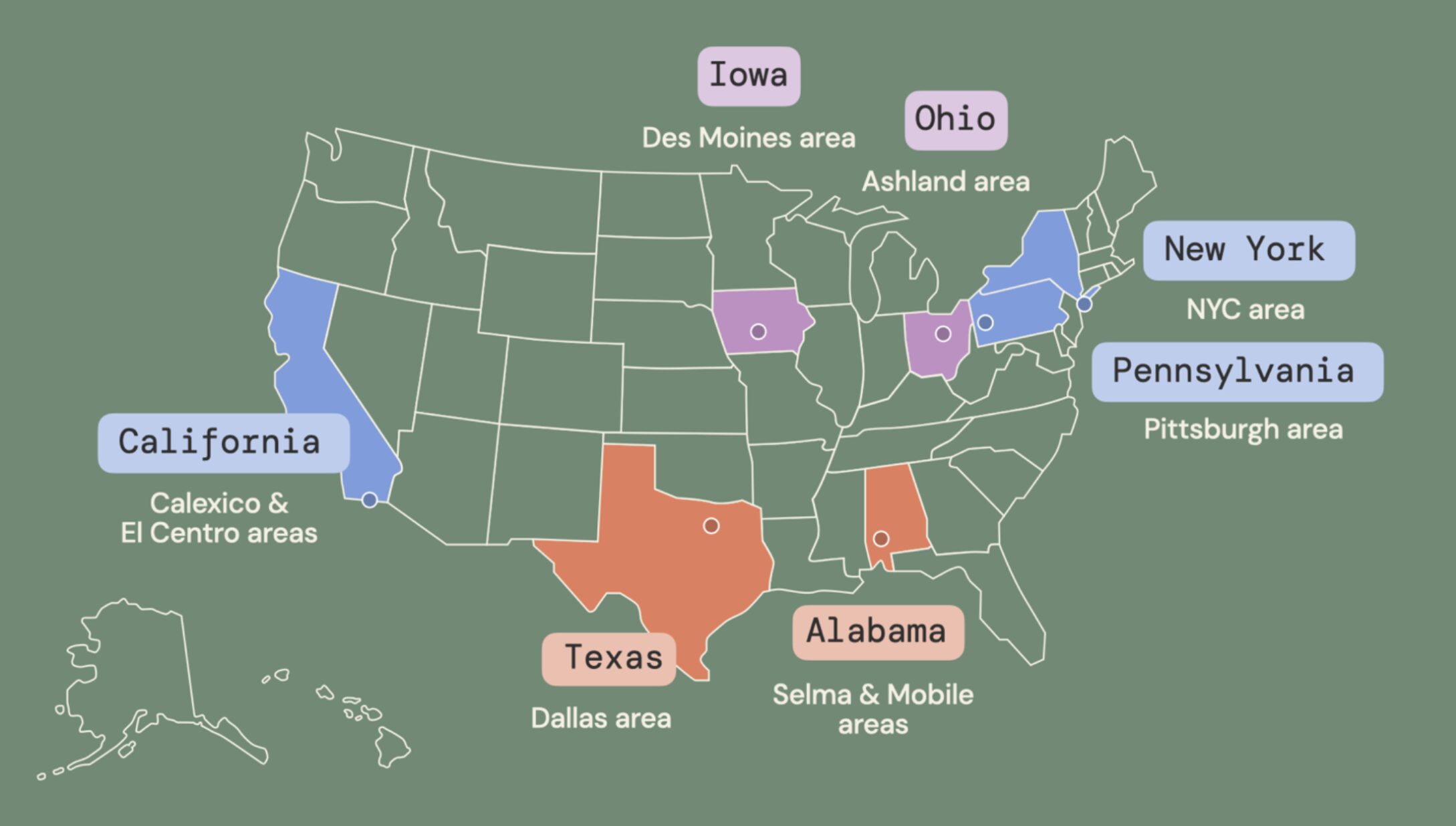

Research Locations

According to the US Dept. of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Community Living, in 2020, 51% of Americans aged 65 and older lived in nine states: California, Florida, Texas, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, North Carolina, and Michigan. We conducted in-depth human-centered research activities in five of those states – California, Texas, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio – as well as in Iowa and Alabama.

Fig. 6. Research took place in seven diverse communities across the country. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

The locations represent diverse geographic areas, population densities, political leanings, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regions. We additionally selected four states in which more than 10.7% of the population is dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

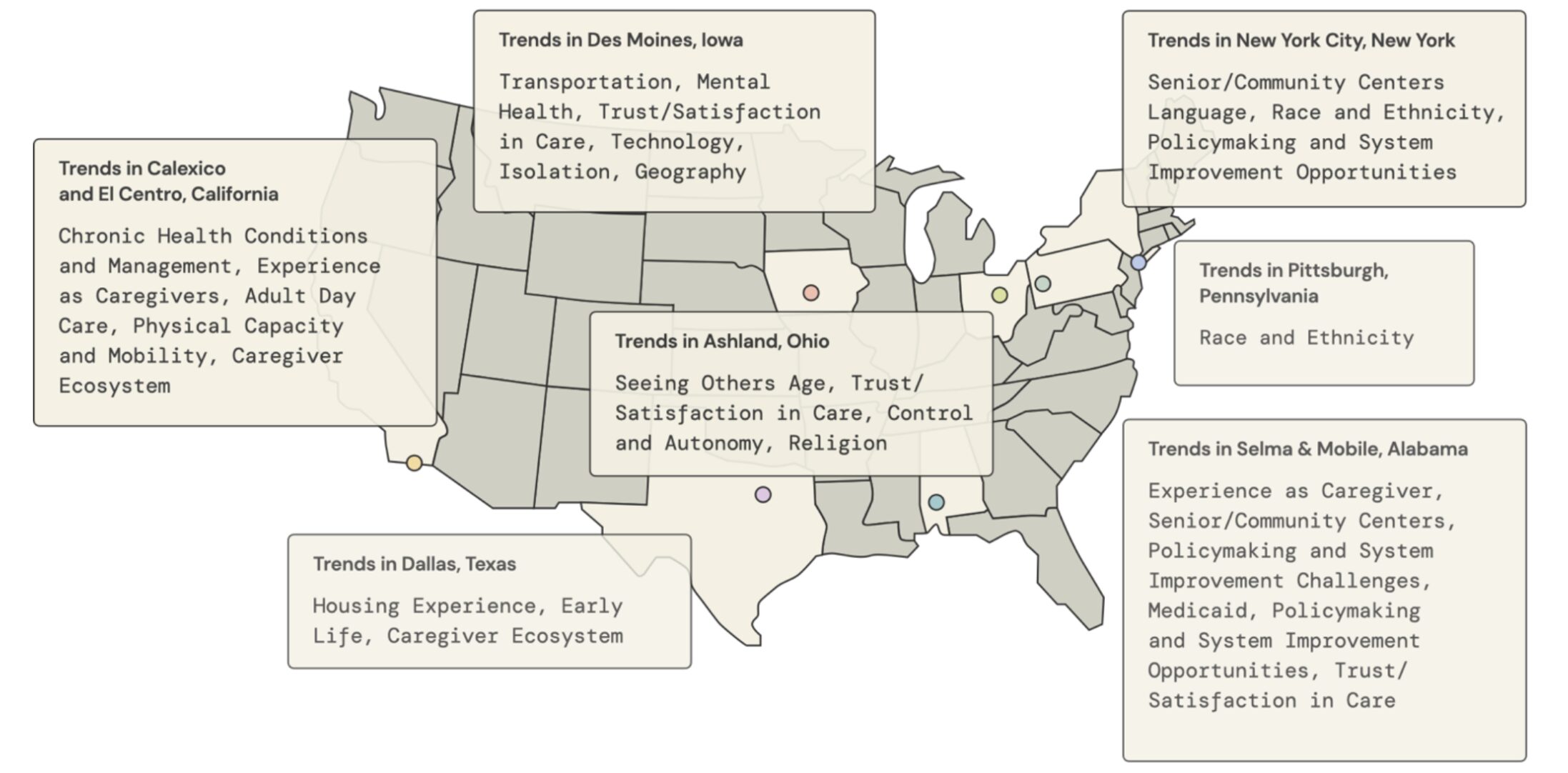

By concentrating research in a set of locations, rather than finding 66 participants in 66 different places, we sought to gather community-level trends, in addition to individual-level experiences. Ultimately, we were able to observe that some topics were more prevalent in each of our locations than in others.

Fig. 7. For each location, some topic areas were more prevalent in that location than across the whole research pool. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Inquiry Areas

Inquiry areas are broad topics or categories of knowledge that we hope to better understand through research. Inquiry areas apply to all participant or stakeholder types, and they are used to inform research methodologies, discussion guides, and desk research.

To develop our inquiry areas for the Public Prospective Longitudinal Understanding Study of 65+ Adults, PPL collaborated with The SCAN Foundation staff and also examined precedent surveys and studies of older adults. We identified four areas of interest that we believed could be further illuminated through qualitative human-centered design research (see illustration below). These inquiry areas guided our research engagements with older adults, their caregivers, and subject-matter experts:

Table 1. Inquiry Areas for the Public Prospective Longitudinal Understanding Study of 65+ Adults

| Older Adults’ Lived Experience | Policy and System Interactions |

| What are older adults’ experiences, needs, and preferences around aging? | How do policies and healthcare systems currently respond to older adults’ needs and preferences? |

| How do identity and culture relate to older adults’ needs and preferences and the success of existing services and policies in serving them? | How could policies and healthcare systems change to support older adults better? |

Research Recruiting

We recruited our cohort of 66 older adults through Area Agencies on Aging, local senior centers, and institutional and academic connections of the project’s 25-member advisory committee. Recruiting materials were also distributed on social media and printed and posted at high-traffic areas at community-based organizations’ physical locations and other community hubs.

As noted above, our aim was to assemble a research pool that over-represented people of color, lower-income people, and people who live in rural areas. This is a form of intentional sampling bias intended to elevate voices that are often underrepresented in policy decision making. As we had commitments to public sharing of data and to longitudinal research, we also made it explicit during recruiting that participants should be willing to allow us to share their data publicly and to participate in future research.

We were mindful of avoiding other unintended biases – for example, recruiting only individuals who are well connected to community networks or have better-than-typical literacy and technology skills. PPL’s practice when working with community recruiting partners is to ask them to connect us to potential participants, but PPL then independently screens individual participants, ensuring that partners don’t only provide us only with ‘model’ participants.

All participant-facing materials were written in plain language to ensure they were accessible to a wide range of participants. Key materials were also translated into Spanish and Chinese (both traditional and simplified) in order to reach participants whose primary language is not English.

Fig. 8. Flyers were produced in English, Spanish, and Chinese, and interviews took place in all three languages. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Conducting Research

Semi-Structured Interviews

Pairs of researchers conducted semi-structured interviews in participants’ homes or in agreed-upon community spaces, such as senior centers, churches, and libraries.

Before beginning, we walked participants through a comprehensive consent process that explained the project, described how the information collected would be used, and offered contact information for questions or concerns. While all PPL projects include a detailed consent process, this project required special care, given that we were asking participants to consent to public sharing of their data. While we had specifically recruited participants who were open to public sharing, a few participants did decide, during the consent process, that they were not willing to have their face and/or voice be recognizable in shared outputs; we either filmed them without capturing their face, or we subsequently blurred or disguised their visage and/or voice in material posted to the public platform.

Our in-depth interviews focused on older adults’ experiences of aging and accessing healthcare and other services. Our goal in semi-structured interviews was to use our inquiry areas as a guide, but not to follow a predetermined script or matrix of questions. We aim to create an environment where participants feel comfortable, allowing our professional qualitative researchers to explore interesting stories as they emerge during the engagement. We carried lightweight equipment – just a tripod, light, and small microphones – to minimize the intrusiveness of recording.

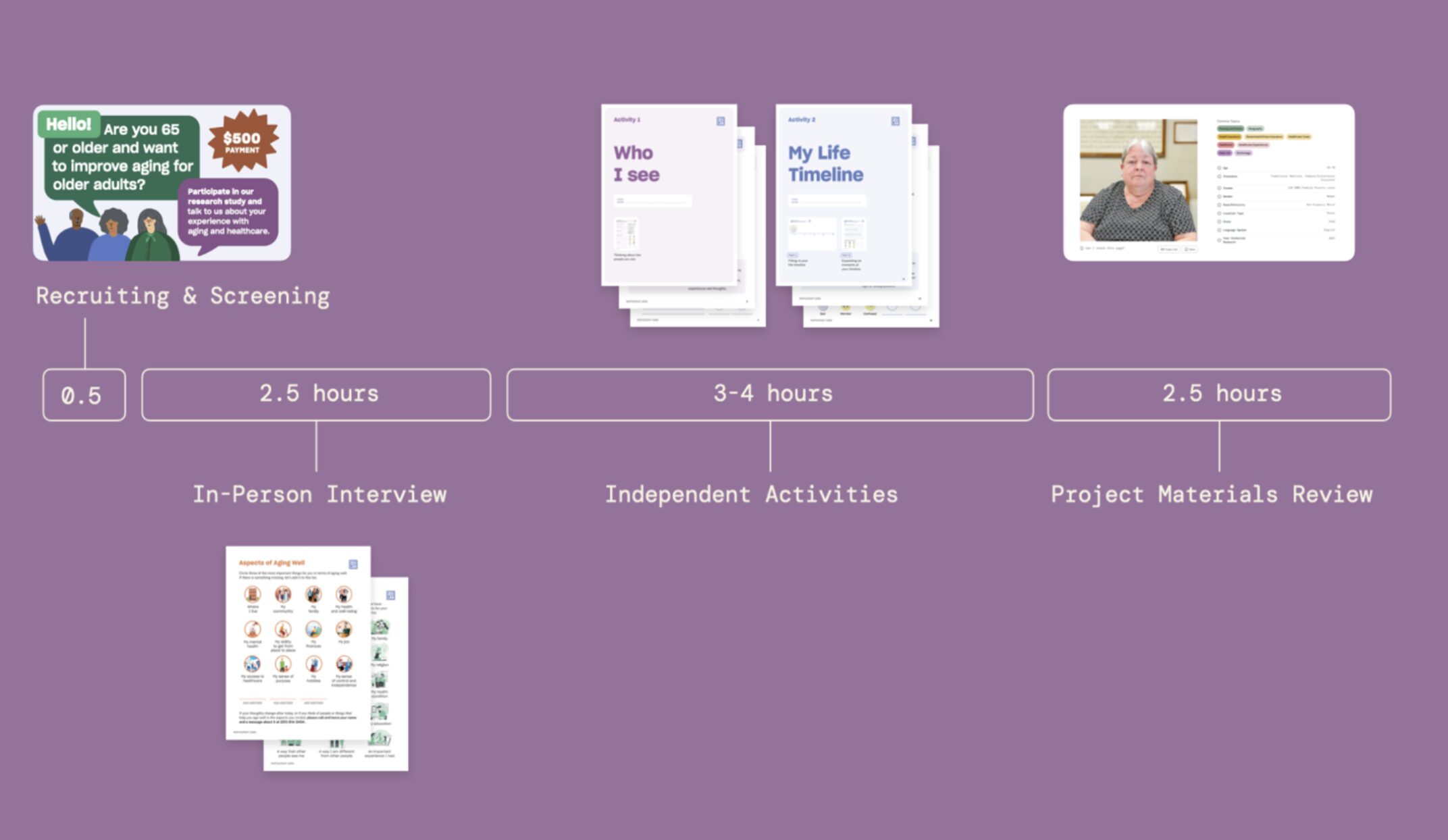

Teams traveled directly to participants for these in-depth conversations, leaving behind a packet of independent activities to be completed over the following weeks and returned by mail. Our researchers conducted interviews in English, Spanish, or Cantonese, and activity materials were provided in the participants’ preferred language.

Fig. 9. A PPL researcher conducts an interview with an older adult. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Cultural Probes

The first activity we provided for participants to complete on their own was called Who I See. It asked them to map their social network by filling out worksheets about the people they see on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis, including friends, family, and care staff, and also to describe what those interactions are like and how they feel.

The second activity, My Life Timeline, prompted older adults to chart their lifetime milestones of aging – along with their hopes for the future – and to provide more detailed explanations about a few of those moments.

Almost all of our participants returned these materials to the research team, and they are fascinating windows into people’s past experiences and current social networks. We have included scans of the timelines on the public platform, scrubbed of personally identifying information. The social-network probe artifacts proved too challenging to make publicly available, given references to names and details of non-consented members of our participants’ community; these materials were used to inform our insight briefs, however, and could be further analyzed in future rounds of research.

Project Materials Reviews

All older-adult participants were provided with copies of all their data units, in their original language, in advance of site launch. We asked them to indicate if there were any items that they did not want to have published. Based on this review, we removed three units of data, from one participant. All of the nearly 2,400 data units remaining on the site have been approved for public sharing by the participants.

Fig. 10. Participants sat for interviews, completed independent worksheets, and reviewed site data. Image courtesy of the Public Policy Lab.

Research Compensation

Older-adult and caregiver participants who took part in all activities provided about ten hours of their time. Participants received $200 for the initial interview and received up to a total of $500 if they participated in follow-on activities. Expert members of our advisory committee were also asked for about 10 hours of time and were offered an equivalent honorarium (which many declined). Our $50-per-hour compensation rate is intended to match or exceed the rate of pay of an entry-level PPL staff researcher.

Building the Platform

Taxonomy and Tagging

A primary goal of The People Say is to provide access to a qualitative dataset that enriches and expands on the quantitative data about older adults that’s typically referenced by policymakers. To make our data more directly associable with existing quantitative data, our 108 topic and subtopic tags were developed with reference to the primary keywords or taxonomies used by five major longitudinal studies of American older adults, specifically:

- The Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) – Aging in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities for Americans

- Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS)

- National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS)

- Older Americans 2020: Key Indicators of Well-Being

- 2023 Profile of Older Americans

With those studies as a starting point, we developed a taxonomy to categorize the content included on The People Say. Every data unit included in our database is tagged per this taxonomy. You can filter our database by these tags when you search the database; additionally, on any given data-unit page, clicking on any topic or subtopic tag will generate a result of all data on this site with that tag.

To make it easy to find quantitative data that augment our qualitative data, on each one of our data units, we’ve also provided links to related data in summary reports from the sources above (except the MCBS, which doesn’t have an easy-access summary report).

Approximately 40% of our subtopic tags do not have related data in the quantitative surveys. We think this speaks to the meaningful difference in the kind of data that in-person, human-centered research can generate. Our participants shared aspects of their lived experience that survey instruments are unlikely to collect.

Development and Testing

The People Say has been designed primarily for three major user groups: 1) legislators, policymakers, and their staff; 2) federal, state, and local program leaders; and 3) researchers and advocates. Our 25-member advisory committee includes representatives of all of these user types, and they helped us iterate on the tagging taxonomy, even before we began site development. As an example, federal policymakers and program leadership felt that it was important to be quite specific in tagging data related to different various federally funded benefits programs, so we have specific tags for Medicare, Medicaid, veterans’ programs, etc. Once in development, we also tested with users recruited from the workplaces of our advisory committee members at two different stages of development.

While focused on those three primary user groups, we’ve also designed the site to be usable by older adults and anyone seeking to learn how to better support their aging loved ones and community members – and what to expect when growing older themselves. While we did less user testing for these user groups, we did conduct sessions with several of our older-adult participants who use websites (only about a quarter of our participants are comfortable using online tools). We tested their ability to navigate the site, review their data, and also review that of others; this user testing, as expected, provided some useful additional information around accessibility and ease of use.

Launch and Immediate Impact

Launch Event

We launched the site on July 11, 2024, at the U.S. Capitol – an opportunity provided to us based on the relationship between a partner at The SCAN Foundation and the Senate Committee on the Aging. In attendance were staff from two House and Senate committees, member staff from the offices of three senators and four representatives (five Democrats and two Republicans), representatives from six federal agencies, and staff from 22 research, advocacy, and stakeholder organizations.

We were also joined by two of our research participants and their family members – from Iowa and Pennsylvania – and we conducted a Q&A with them about their stories, their participation in the project, and what they hoped policymakers and program leaders would take away from hearing about their experiences of aging where they live.

Fig. 11. The launch event for The People Say was held on July 11, 2024, at the US Capitol Building. Image courtesy of McCabe Message Partners.

Immediate Impact

Reaction to the launch has been very positive – and it’s already having an impact on efforts by the federal government to better incorporate older adults’ points of view in policy decision making. The Interagency Coordinating Committee on Healthy Aging and Age-Friendly Communities(ICC), established by the authority of the Older Americans Act, is developing a national framework on aging that can support older Americans in aging in place, while accessing preventive healthcare and long-term services and supports. A key goal of the ICC is to hear directly from older adults – particularly those with the greatest economic and social need – to ensure policies are reflective of needs and preferences.

Working with partners at The SCAN Foundation, a National Plan on Aging Community Engagement Collaborative partner with the ICC, PPL is currently gathering this input during the summer of 2024 by facilitating listening sessions that amplify the voices and lived experiences of older Americans. We’re organizing listening sessions in three of the communities where we established relationships during the creation of The People Say, and existing members of our participant pool have been invited to join those sessions. During the listening sessions, older adults will meet with federal officials and discuss aging and the four domains in the national framework: Age-Friendly Communities, Coordinated Housing and Supportive Services, Increased Access to Long-Term Services and Supports, and Aligned Health Care and Supportive Services.

We think that this example – of policymakers’ direct engagement with older adults’ experiences – points to the immediate value of constituting ongoing research pools for civic research.

Lessons Learned

Development of The People Say has been both immensely challenging – and also terrifically gratifying. We believe that lessons learned during this project will be very helpful in developing similar subsequent work.

Unanticipated Challenges

The project was scoped based on our past experience conducting national-scale qualitative civic research. But even that past experience did not prevent us from experiencing a whole range of challenges, especially relating to the multimedia and public aspects of this project. With hindsight, many of these difficulties seem obvious! However, we apparently had to learn the following lessons the hard way:

Recruitment Partners Could Not Substitute for Team Recruiting in-Person

Recruiting is often time-consuming, but we’d anticipated that warm connections from our advisory committee to on-the-ground organizations that serve older adults would be valuable in connecting us to participants. However, those introductions did not always yield capacity or willingness to help us recruit. Cold outreach to community organizations was less than reliable because most senior centers had no reason to believe in our legitimacy over the phone, and they typically did not respond to email. Ultimately, we found that in-person intercept recruiting at sites was more valuable than attempting to leverage local staff to recruit.

Data Collection Overwhelmed Data Processing

We have a standard notetaking protocol. Nonetheless, researchers who did not rigorously enter data and quotes into our database as soon as possible post-interview eventually fell far behind in preparing this data for public presentation. If we had been able to stick to our original plan to alternate field-research weeks with stay-at-home weeks, we might have fared better – but that intention collapsed under staff and site scheduling challenges.

Translation Was an Enormous Effort – and Robots Created Problems

Our team members fluent in Spanish and Cantonese translated discussion guides, interview materials, and subsequent outreach materials. These were more time-intensive efforts than anticipated, but still feasible. However, the generation of transcripts, video subtitles, and textual data units for interviews conducted in Spanish and Cantonese was a much larger task than anticipated. We remained committed to presenting all these materials on the site in the original language as well as in English, to preserve their legibility to the participant and other users. We hoped to rely on AI-enabled transcription to do the translation heavy lifting, but AI tools introduced transcription errors that had to be corrected manually – in both languages – for dozens of hours of interview material.

Habits From Non-Filmed Research Created Problems in Filmed Data

We’re used to building rapport during interviews by speaking conversationally, addressing people by name, etc. These habits have minimal negative effects when using and scrubbing written transcripts, but proved more problematic in compiling our filmed data. We talked over our participants at times, and both we and participants used personally identifiable information – all of which had to be cleaned up in our final video artifacts.

Film Quality Undershot Our Aspirations

As this project was both an experiment in collecting significant amounts of video data, and also a fast-paced effort with multiple simultaneous teams in the field, we erred on the side of lightweight, low-cost filming using mobile phones. That decision, while expedient, led to predictable variations in video quality. Overall, while we’re happy with the research value generated by our video artifacts, we’ve been disabused of any notion that we might create satisfying artistic filmmaking with amateur tools and technique.

The Ethics of Public Data Creates New Requirements

Preparing multimedia data for a public platform is very different than collecting it for internal use: Each transcript (and its translation, when the original engagement was conducted in a language other than English), as well as all audio/video clips and the timeline cultural probes, had to be thoroughly scrubbed of PII before they could be added to the public platform. Additionally, we decided to print out all data units and ship them to participants for their review and approval in advance of launch – this was not a commitment we made when consenting our participants, but the research team decided it was further valuable assurance that we were not exposing data that any participant would rather not have made public.

As Always, Human Alignment Is the Most Challenging Work Product

We know that the hardest work of any project is aligning the mindsets, expectations, and work processes of the partners and the teams involved. And yet: we underestimated the necessary rounds of multi-partner approvals, failed to get our own internal team in advance agreement over the final production and soft-launch timeline, and complicated our software development process with fuzzy feature scoping. Every future project is a chance to not do that again!

Unexpected Successes

Despite the challenges, the work also yielded some unexpected satisfactions.

Outputs Blossomed Past Original Intentions

We’d assured our partners that we’d be able to generate some insight artifacts as outputs of research synthesis. We imagined a set of static materials capturing the collective experiences of our participants. As we began to develop a set of insight papers, it became easy to iterate on how they might live on the website: they could preface a collection of video clips sorted into subthemes; they could be complemented by a section on the relevance of policy to affecting that insight area. These insight pages have become a primary way to invite both users and casual browsers to draw meaning from the data and to become invested in what it could mean and motivate.

Rich Media Is Super Compelling

We’d hoped that the investment in creating video research would yield greater engagement in participants’ needs and aspirations – and so the powerful response generated by the video data has been heartening. We have had many requests to play and use the clips even since we shared a first sampling of them in February 2024.

Listening Is Transformative

Many of our older-adult participants expressed how validating it was to participate in this work, to be asked to tell their stories and to have their stories heard. And the work was also deeply gratifying and even life-changing for our researchers. We got Christmas cards and Lunar New Year’s greetings from our participants. We got hugs. And we got the benefits of their decades of life experience, with profound learnings both on what makes the last third of life painful – and what creates joy and meaning.

What’s Next

This project is intended to serve as a test case for public multimedia civic research – it’s our intention to build on the lessons above by expanding the platform in a variety of ways.

Longitudinal and Expanded Research with Older Adults

An important next step for this work is to conduct subsequent rounds of research with our participants. We believe that tracking the evolving needs of older adults over time will generate important insights into persistent and/or recurrent challenges that can be addressed by policymakers.

We’re also interested in expanding our research pool, both to add additional geographic locations and to include additional populations of interest, such as older adults living in residential care settings, older adults in need of at-home care, older adults who are/have been homeless, Indigenous older adults, and/or formerly incarcerated older adults.

Public Civic Research with Other Populations

We developed The People Say with a focus on older adults – but also to demonstrate the potential for public, prospective, longitudinal civic research.

We’re interested in applying the same approach to developing other longitudinal research studies with populations of interest, such as moms (re: prenatal, birth, and post-partum experiences and services) and working families (re: access to healthcare/benefits, job quality, education/training opportunities, social connection, and other aspects of economic mobility), or in other specific geographies, such as New York City or Michigan.

Extending the Platform to Other Civic Researchers

In addition to using the platform to house research conducted by the Public Policy Lab or for The SCAN Foundation, we also want to support other civic researchers with a commitment to high-quality, ethical design research to make use of the platform, creating a kind of ‘GitHub for civic research’ – a repository for the work of multiple civic researchers.Options we’re interested in exploring include both adding other research data to the existing The People Say data set and creating new public data sets that use the same platform infrastructure.

Conclusion

While we have further aspirations, we’re pleased that The People Say demonstrates a meaningful effort to address the major limitations in civic research practice that we outlined in our introduction above:

- Creation of our standing respondent pool, comprised of a deliberately inclusive group of participants, is already allowing us to more easily and quickly recruit diverse members of the public to participate in civic research, as in the ICC listening session example above.

- Partner organizations are expressing interest in supporting ongoing, longitudinal research with the participants, rather than the one-and-done model that’s typically pursued.

- We’ve demonstrated that it’s viable to conduct civic research that respects participant informed consent and agency while generating public outputs.

- We’ve established a functional model for that participation to be paid – and for compensation of all participation to be equitable.

- We’ve shown that civic research doesn’t have to be proprietary – it’s not just possible, but valuable to put civic research data into the public domain. We hope this is a first step to reducing the need to re-study these exact same issues with the same populations.

- Members of the public who participated in the project have visibility into what we collected from them and how their data has been tagged and used in aggregated outputs.

Our ultimate goal, of course, is that our civic research serves to highlight the insight of (often marginalized) people and to shift systems to meet their needs and aspirations. We look forward to building on this precedent to meet that goal.

About the Authors

Chelsea Mauldin (she/her) is a social scientist and designer with a focus on government innovation. She directs the Public Policy Lab, a nonprofit organization that designs better public policy with low-income and marginalized Americans.

Raj Kottamasu (he/him) is a designer, researcher, and strategist balancing priorities for equity, service, and relationships with systematic approaches to collaboration. At the Public Policy Lab, he leads projects and helps to guide design and strategy across the organization. He served as the research lead for The People Say.

Petey Routzahn (he/him) is a hands-on, brains-in designer who creates physical and digital artifacts that help people better understand the world around them and navigate the built environment. He served as the project lead for The People Say.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the thoughtful feedback of Victoria Lowerson Bredow, our EPIC curator, as well as the many people and organizations that made this project possible, including: our partners at The SCAN Foundation, Narda Ipakchi and Kali Peterson; the rest of the PPL project team and our tireless corps of video translators and editors; our expert advisory committee; staff at community-based organizations across the United States who provided support during our research fieldwork; Greater Good Studio; McCabe Message Partners; and our web-development partners at Make Repeat. And, especially, our older-adult and caregiver participants – it was an honor to share their insights.

References Cited

Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2024. 2023 Profile of Older Americans. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Profile of OA/ACL_ProfileOlderAmericans2023_508.pdf

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of Enterprise Data and Analytics. 2023. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. https://www.cms.gov/data-research/research/medicare-current-beneficiary-survey

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. 2020. Older Americans 2020: Key indicators of well-being. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://agingstats.gov/docs/LatestReport/OA20_508_10142020.pdf

Freedman VA, and JC Cornman. 2023. National Health and Aging Trends Study Trends Chart Book: Key Trends, Measures and Detailed Tables. 2011–2021. https://micda.isr.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/NHATS-Companion-Chartbook-to-Trends-Dashboards-2021.pdf

University of Michigan Health and Retirement Study. 2017. Aging in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities for Americans. https://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/databook/inc/pdf/HRS-Aging-in-the-21St-Century.pdf