The aim of the research was to discover how teen girls use technology in relation to privacy practices in their everyday lives. Asking teenage girls to describe the worst technology they could imagine was a fruitful way of exploring their feelings towards location-awareness, tracking and surveillance in particular and served as inspiration for the design of concepts which embody many of their concerns.

INTRODUCTION

This study explored how teen girls currently understand and create both privacy and “publicness” in their everyday lives. We also wanted their view of the potential impact on their privacy of technologies such as location-aware computing. How do they feel about technologies that reveal their locations to their families and friends?

Prior studies on teenaged girls’ use of SMS messaging (texting) or PC based instant messaging (IM) show that the silent nature of these two forms of communication makes them easy to use when other people are present, and a preferred means of private communication with friends for teenage girls living at home. Studies of Japanese girls and texting carried out by Ito and Okabe (in press; n.d.) suggest that phone based email or texting allows teenage girls in Japan to maintain their “intimate community” of friends. Studies of teen texting in the UK by Grinter and Eldridge (2001) also pointed to texting as a cheap and fast, but also silent, method of communication. Studies of IM use in the US by Grinter and Palen (2002) were undertaken when few US teens had cell phones, and suggested that IM was the preferred technology of US girls who want to carve out a personal and private space within the home.

The study described in this paper set out to explore the role that technologies play in creating, maintaining and preventing privacy in the lives of older teenage girls in the US and UK and whether the girls in the US still used IM rather than SMS. All the participants were living in a parental home and attending school full-time, and we studied how they used their cell phones, PCs and other forms of technology to enable private communications at a time in their lives when they desire to be in constant contact with their friends, and yet are subject to surveillance by parents and teachers.

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were 24 teenage girls, aged between 17 and 18. Five were from Portland, OR, eleven from Seattle WA, in the US and eight from the UK; evenly divided between Brighton and Bristol. They were recruited in friendship groups, with the initial contact bringing one or two friends. They were paid for their participation, and consent forms were obtained from each teenager, together with a parent if they were under 18.

The girls were all in full-time education, and were all living with one or more parents, though 46% of the girls had divorced parents and either lived with just one parent or switched between the homes of both parents.

As a prerequisite for participation in the study, all of the teenagers had cell phones and access to a computer with internet access. Three of the UK girls had a computer but did not have internet access at home, and used school or friend’s computers to participate in the study. They were all provided with a digital camera for data collection, and kept as part of their payment.

METHODOLOGY

Each group of two or three girls had an initial meeting with one of the researchers and then participated in a joint photo blog for two weeks. In-depth individual interviews were held at the end of the blogging period. Quotes and photographs from the blogs and interviews were then used to design concepts that expressed “the worst technology” for girls.

Blogs

The blogs were set up by the researchers and posed one question per day, which each participant answered with text and photographs. They were also asked to add journal entries to provide information about their days. We wanted to capture data about everyday experience, emotion and ephemera, and to gain an insight into teenage life from a distance.

Only one of the participants in the study had a blog prior to the study, using LiveJournal, but all were aware of them. In the first group of three girls we gave each an individual blog, as an attempt to provide privacy, but that negated the role of the friendship group. It seemed that if they shared a single blog they might communicate more, both with each other and with the researcher, so we gave all the subsequent groups a shared blog. Whether the girls saw each other during the day at college, and whether their blog partner was their best or less close friend affected their levels of openness when answering the questions. The most engagement with the blog came from close dyads that went to different schools and used the blog as a form of chat. The girls also reported during interviews that the blog provoked conversations with one another that would not have otherwise occurred.

One of the author’s previous research studies with teenagers had involved giving them a journal and camera to record their thoughts and practices. This time blogging was used as a way of collecting their writing and photos, but with the additional bonus of being able to interrogate the girls further while their thoughts were still fresh. One of the girls had participated in both the studies and was asked to compare her experiences with the book and the blog.

With the book I was so much more creative, I could do so much more. I felt my personality really showed… But I couldn’t see the book being so much fun if both L and I were doing it. It was better since we were friends and we could see what we’d both written without having to go over to her house and say, so, what did you write?

Interviews

At the end of the blogging period the researchers interviewed each of the girls individually. Interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes and used mapping exercises to talk about daily living patterns. The girls drew maps to explain the layout of their houses, the places they went and their friendships. The house maps revealed information about how the siting of technology in combination with the layout of their home dictated their privacy practices. Maps of where they went were used to talk about what they told their parents about their location and maps of friends revealed more about how they kept in touch.

FINDINGS

Privacy as principle

Maybe not surprisingly, it was apparent from the blogs and interviews that privacy was extremely important to all the girls as a matter of principle. Privacy for teenage girls is about defining the self as an individual and an adult, and is part of an ongoing negotiation of boundaries.

Because I am living at home, I do realize that there is only so much privacy still aloud (sic), but my parents are really good about giving me that space. I feel privacy is something that you can have without having to always explain yourself and your actions and it is very important to me.

The fact that privacy is not necessarily about highly secret content was also a common theme:

It doesn’t have to be anything big, I just don’t want to tell them… I don’t want to know where they’re at all the time…it’s something of my own, when I leave my house I’m doing something of my own, something on my own…it’s more my time… Home life and outside of home life is different. It’s a secret life, you know.

Finding privacy in the home

All of the girls saw the main living areas of the house as public rooms which were primarily a parental zone and not really their space. In order to create privacy for activities or conversation they either went to their bedrooms; moved within the home to somewhere they could not be overheard, or moved outside the home altogether to a car or public space. Acoustic privacy was far more important than we had supposed as the majority preferred voice communication and were not using texting and IM for silent communication in the ways that had been previously suggested by the studies of Ito and Grinter.

The only times they felt able to use the family spaces were when parents were out and they could take over, or if they had so many friends over at one time that their parents were forced into another part of the house. While drawing maps of where they go one of the most frequent destinations (especially in the US) was friends’ houses. The most popular friends’ houses were those with parents who were out at work until late, or were large enough to provide physical distance between the teens and the parents.

The majority regarded as their bedroom as a private space, including one of the three girls in the study who shared bedrooms, but only 70% said that a closed bedroom door gave them privacy. T describes her non-private bedroom:

Unfortunately there is no lock on the door so my Mom sporatically (sic) bursts in when i am changing or when I’m with my boyfriend. also the walls are very thin so even when i am having a private conversation on my cellphone i have to whisper so my brother can’t hear.

The inhibiting effect of the presence of others, usually parents but also siblings, was a recurrent theme for all girls. LI; “I’ll leave, I never make a phone call or take a phone call in front of my mum. I don’t know why, even if it’s completely innocent I don’t know why I just don’t feel comfortable.”

Whether phone calls were private depended on the layout of the house and how far their bedroom was from their parents’. A described her careful considerations of whether her parents can hear her conversations when they’re in their room, which is next to hers; “I’ve thought about that. If they’re on the phone I’ve listened to see what I can hear, to work out how much they can hear…You can’t hear much …at night, I just turn on my TV.”

Despite the frequent mentioning of being overheard, it did not seem that texting and IM were being used to create privacy at home; instead the mobility of the phone was used to escape those who might be listening. The cordless phone became a surprisingly important piece of technology as it offered privacy and mobility within the home. All the girls in the UK had or had had a cordless phone that was on the family landline and which supplemented their cell phone (they were all using “Pay As You Go” phones which they funded themselves). In the US all but one of the girls were part of a “Family Plan”, which provided free calling from their cell phone at evenings and weekends, so had less need of the cordless phone.

In order to achieve privacy in the home the phone, whether the family’s (cordless) landline or a personal cell phone, was carried to the most private place in house: bedroom, car, street, sauna, bathroom, closet, garden, trampoline, the room most distant from their mother… were all listed as places to go to with a phone in order to have a private conversation. For instance K described phone calls in her bedroom closet; “if there’s something I really don’t want my parents to hear I’d go in my closet. I can go in there and sit down…to talk on the phone sometimes.” There were several stories of parents overhearing their calls, and ensuing conversations about things they just didn’t want to talk about. As has been previously stated this was not necessarily because the conversation was about highly sensitive topics, rather a sense of it being their own private life.

Texting and IM were not seen as more private because the content might be read by others. Texting was seen as useful mostly for quick, ‘functional’ communication, such as sending a text to check if a friend was at home before ringing on their landlines. This enabled late night or discreet calls between friends who were primed to pick up the house phone on the first ring. It also meant the parents paid for the cost of the call. This agrees with Grinter and Eldridge’s study in the UK (2001).

The sense of privacy when using the computer also depended on its location within the house and whether it is shared. Computers which sat in a shared space were most open to parental scrutiny, but any computer that was used by other family members did not feel private and one girl described how she had made herself the administrator so she could protect her creative writing from her mother. 44% of the girls in the US had a laptop or PC that was theirs, which gave them the ability to take the device, and the communication it contains, to a more private place such as their bedroom.

I have my own computer, …. It is a laptop and i love it; it’s name is Poppy. i have it in my room so that is REALLY nice… i can use the computer for what i want and my parents don’t get up in my business.

The only girls who were frequently using IM were the US ones with access to a personal computer or laptop, and one UK girl with lots of family in Peru.

Privacy and mobility

The cell phone enabled all the girls to provide ad-hoc location updates to their parents, and renegotiate curfews as required. The very existence of the phone, and the knowledge that parents can call their daughters at any time had given them far more mobility outside of the home, and thus more privacy. Knowing that the girls would be carrying the phone often meant that there was very little prior communication about where they were going. At the same time the ability to call at any time meant that several of the girls had assigned special ring tones to parents in order to “censor” the environment before answering the phone, and at other times used the ambiguity of the technology to avoid unwanted communication with both family and friends.

The girls appeared less worried about location tracking than we expected. Only a couple of the girls were really worried about their parents knowing exactly where they were, and this seemed more of a concern in the US; maybe because the legal age for drinking alcohol is 21 and the places they were concerned about were the homes of friends who were known to have parties involving alcohol. Several girls felt it would be more of a problem with friends or boyfriends, as they carefully juggled social groups.

THE WORST TECHNOLOGIES

Asking teenage girls to describe the worst technology they could imagine provided an interesting approach to revealing their feelings towards location-aware, tracking and surveillance technologies. The girls were quick to describe their worst technologies as those that would reveal exactly what they were doing or saying, either through video, audio or text. Only one girl had a blog outside of the study, for which she carefully administered viewing rights after her parents read it, and only one girl had a paper journal which she carried with her at all times. Several noted that they were wary of email and instant messaging as text could be copied.

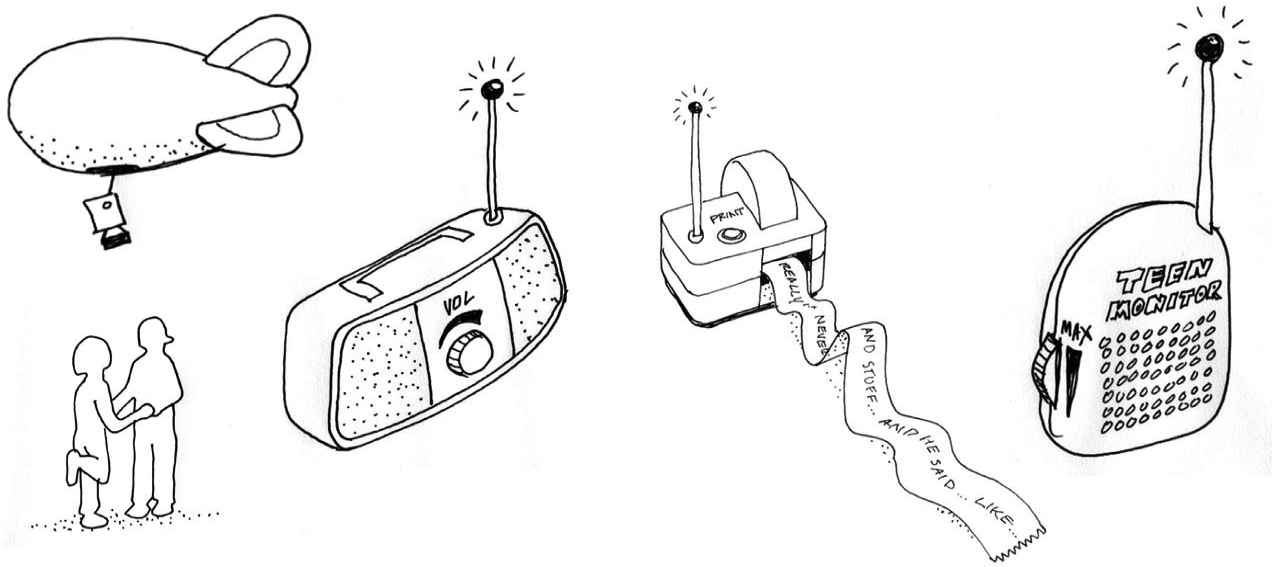

The following concepts were directly inspired by the girls’ descriptions of worst technology. Each idea includes the quote that inspired it, plus a simple sketch and description of the imagined product. The ideas are meant to highlight their concerns, especially about revealing the everyday content of their lives. The concepts were posted to a blog and the girls were invited to provide their feedback.

Family Video

Family Video lets you stay part of your child’s life, even as they grow up and spend more time out of the house. A small video camera attached to a flotation device acts as a personal CCTV which sends back a constant video stream to home. The video can be seen on any display in the house; special events could be watched on the big screen TV.

Response from L: “This is super awkward! I couldn’t even imagine all the horrible things that would arise if that followed me around. This is probably the overprotective parent’s dream!”

Constant Connection

Constant Connection provides a continuous open communication channel for parents and children. The connection can be maintained between two mobile devices, or the parents can use the home audio device, which is ideally suited for a kitchen counter.

Response from T: “the last thing a teenager wants is to bring their parent in their back pocket to the movies or to a party. Being a teen means your trying to separate from the nest and assert yourself as a confident, competent individual.”

Ticker Text

Ticker Text converts all communication from designated cell phones into an easy to read text format. Each text message that is sent or received on the phone is printed out on a paper roll. Phone conversations are also now easy to read and archive using speech to text technology.

Response from L: “As for the phone conversations being written, another not so good idea. My sister was grounded for a while after she accidentally recorded one of her phone conversations and my parents found it.”

Teen Monitor

Teen Monitor provides a simultaneous broadcast of all your teenager’s conversations through an audio speaker in your home. A small and inconspicuous microphone picks up all their phone calls, and everyday conversations with friends, so you’ll always know what’s going on in their lives.

Response from C “Definitely up there on the creepy scale… the only time that I can see this device or any of the others for that matter, as justifiable is if it were used to monitor a teen that was otherwise uncontrollable and was endangering themselves or others with their behavior. Basically the extreme problem child.”

FIGURE 1 Sketches of worst technology concepts. Family Video, Constant Connection, Ticker Text, Teen Monitor.

CONCLUSION

The girls in the study were using the mobility of technology to create and maintain privacy. The cellphone meant they no longer had to risk being overheard because they either left the house entirely, or within the house the cellphone or the cordless phone allowed them to escape out of earshot.

The worst technology for girls is really something that invades their privacy, and discloses the content of their lives: what they are doing, saying and writing. Mylifebits and SenseCam from Microsoft research, Lifeblog from Nokia, and the Eyetap system from Steve Mann are all experiments in the kind of technology that these teens most worry about: collecting images, or a constant video stream, or audio recording, everything you write, your IM sessions, or emails. If combined with CCTV, then their worst nightmares would be in place. What they feared most was the combination of what Nack (2005) calls “see what I see” and “see me”.

Acknowledgments – Nick Oakley for his help with concepts. Colleen Romike, for her help with the Portland research. All the participants in the study who were so generous with their lives.

Wendy March is a Senior Researcher within Intel Research. As an interaction designer Wendy is particularly interested in translating her ethnographic research findings into new concepts and future scenarios. Since joining Intel her work has included both design and ethnographic research in the US, Europe and Asia.

Constance Fleuriot is a freelance consultant in user research and locative media design. Until September 2005 she was a principal investigator on the DTI-funded Mobile Bristol Project, investigating the social impact of emerging pervasive and mobile technologies, their potential use in and effect on everyday life. She is now a consultant and facilitator on location based mixed media projects with a variety of user communities, as well as developing collaborative theoretical work on developing a descriptive language for locative media.

REFERENCES

Aoki, Paul and Alison Woodruff.

2005 Making space for stories: Ambiguity in the design of personal communication systems. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Association of Computer Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Computer-Human Interaction, Portland, April.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby.

2001 Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Basel: Birkhauser.

Gemmel, Jim, Gordon Bell, Roger Lueder, Steven Drucker and Curtis Wong

2002 MyLifeBits: Fulfilling the MEMEX vision. Proceedings of ACM Multimedia, pp. 235-238.

Green, Nicola

2002 Who’s Watching Whom? Monitoring and Accountability in Mobile Relations. In Barry Brown, Nicola Green and Richard Harper, eds. Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 32-45.

Grinter, Rebecca E. and Marge Eldridge

2001 y do tngrs luv 2 txt msg? In Proceedings of the Seventh European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work ECSCW ‘01, Wolfgang Prinz, Matthias Jarke, Yvonne Rogers, Kjeld Schmidt and Volker Wulf, eds. Pp. 219-238. Netherlands: Kluwer

Grinter, Rebecca E. and Leysia Palen,

2002 Instant Messaging in Teen Life. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Association of Computer Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, New Orleans, November.

Ito, Mizuko and Daisuke Okabe

In press Intimate Connections: Contextualizing Japanese Youth and Mobile Messaging. In Richard Harper, Palen, Leysia and Alex Taylor, eds. Inside the Text: Social Perspectives on SMS in the Mobile Age. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Nack, Frank.

2005 You Must Remember This. Multimedia, IEEE 12(1) 4-7.

Mann, Steve

Eyetap project: http://www.eyetap.org/.