Case Study—This paper presents a case study of a project on education solutions for Syrian refugees in Jordan conducted between 2015-2017. First, it describes how ReD’s methodological approach provided a unique perspective to studies on refugees. By immersing a team in the day-to-day lives and settings that most Syrian refugees experience in Jordan—i.e., outside of camps and in people’s actual homes—ReD led its client to “think outside the camp,” something that relief agencies and companies often fail to do due to the refugee camp model of humanitarian assistance that, ever since WWII, has dominated the approach to refugees. Second, as a result of its unique methodological approach, ReD uncovered important findings about social networks and technology use and access in Syrian refugees’ homes and communities that ultimately shaped the client’s perspective on solution development. For example, ReD’s team of ethnographers found that nearly all out-of-camp Syrian households had at least one Smartphone in their possession, if not two or more, and that digital devices served as important tools of communication and community-building among people displaced by conflict. Consequently, ReD advised its client to tap into these pre-existing social networks and mobile technologies in order to develop an education solution that best fit refugees’ “real-life” practices. Ultimately, both ReD’s methods and its findings led to a significant impact in how the client strategized on and developed their education solution, and can serve as a broader model for how to approach building services and/or products for displaced populations with access to basic mobile technologies.

“The Jordanian educational/policy response to refugees is broken and will not easily be fixed or tinkered with. Solutions must work around this system.” (Education expert and activist working with vulnerable youth and school dropouts in Jordan)

INTRODUCTION

Ever since I first visited Jordan in October 2015 to research education among Syrian refugees, friends, family, and colleagues have wanted to know: “What’s it like in the camps?” Before they venture any further, however, I stop them: “I don’t work in camps. Most Syrian refugees live outside of camps.”

This, more than anything else I might say, elicits surprise and, to a certain extent, confusion. Outside the Middle East, the photo-stock image of a Syrian refugee camp—row upon row of identical tents and caravans beaded across a dusty, inhospitable landscape—remains firm in people’s minds. In reality, of the nearly 5 million Syrians who have fled Syria since the civil war broke out in 2011, the vast majority reside in low-income neighborhoods in one of three host countries: Turkey, Lebanon, or Jordan. Indeed, according to reports by the European Commission, over 90% of Syrian refugees in Turkey and over 80% of Syrian refugees in Jordan remain in out-of-camp settings, while Lebanon has no formal refugee camps whatsoever.

Still, there is good reason why refugee camps continue to dominate the global imagination today. As anthropologist Liisa Malkki pointed out over twenty years ago, ever since World War II, there has emerged a standardized way of talking about and handling ‘refugee problems’ among national governments, relief and refugee agencies, and other nongovernmental organizations (1996). What is more, she suggests, “these standardizing discursive and representational forms […] have made their way into journalism and all of the media that report on refugees” (Ibid: 386).

The issue is not only one of misrepresentation, however. In practice too, international relief and refugee agencies tend to adopt a camp-centric approach, developing initiatives primarily from within the contained spaces of camps in order to “order the disorder” (Hyndman 2000) of a humanitarian crisis.

Despite the overwhelming attention paid to in-camp refugees, numerous national and international initiatives aim to reach those living outside of camps. Naturally, though, logistics are a challenge. Syrian refugees in Jordan live in towns and cities scattered throughout the country, and transportation is either unreliable or expensive. As a result, many relief and refugee agencies provide transportation services to and from their centers.

While these traditional camp- and –community center -based initiatives, ranging from medical and hygienic interventions to schooling and rehabilitation programs, remain useful and important, they leave little room for innovative approaches that aim to reach refugees where, for the most part, they really are.

This case study aims to demonstrate how, by immersing a team in the day-to-day lives and settings that most Syrian refugees experience in Jordan—that is to say, outside of camps and community centers, and in people’s actual physical and digital realities—ReD Associates challenged the typical methodological approach to studies on Syrian refugees. Rather than focus on the physical marginality of refugees, we explored the ways in which people are in fact highly digitally connected, despite being geographically dispersed. As a result of this methodological approach, ReD uncovered important opportunity areas for an innovative and inclusive solution that fit people’s physical and digital realities. Ultimately, both ReD’s methods and findings on technology use and access in Syrian refugees’ homes and communities led to a significant impact in how its client thought about and developed their educational solution for children affected by conflict.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT

While humanitarian responses to the Syrian crisis have typically focused on food, water, and shelter, initiatives that improve and ensure the delivery of education are an increasing concern as the years wear on and many Syrian children remain either out of school or in school systems that are under tremendous strain (see Table 1). Thus far, most educational initiatives targeting Syrian refugee children aim to bolster the preexisting structures of either formal schools (e.g. the formal school system of Jordan) or non-formal education delivered primarily through camps and community centers throughout the region. In doing so, these initiatives rarely benefit from thinking outside the box – or the camp, quite literally – by looking at the opportunity areas that exist in people’s actual behavior around learning and education outside of pre-existing structures.

Table 1. Syrian children in and out of school in Syria and neighboring countries, as of December 2014

| No. of school-age children | In Syria | Total outside Syria | Jordan | Lebanon | Turkey |

| Projected | 5.7 million | 1,205,000 | 238,000 | 510,000 | 350,000 |

| Registered | – | 1,237,668 | 213,432 | 383,898 | 531,071 |

| In formal education | 3.7 million | 399,286 | 127,857 | 8,043 | 187,000 |

| In non-formal education | 196,110 | 54,301 | 109,503 | 26,140 | |

| Out of school | 2 million | 642,272 | 31,274 | 266,352 | 317,931 |

Within this context, ReD’s client, one of the world’s leading education companies, aimed to move beyond a traditional donor-based aid model to develop and implement an innovative and scalable education solution that ensures that children who have been affected by conflict continue to receive a basic education despite the turbulence around them. Jordan was selected as the site of both research and initial solution piloting due to its large population of refugees, its relative safety and stability in the region, and the client’s partner relationships there. A team of anthropologists from ReD Associates was then hired to develop a strategy for education solution development based on ethnographic fieldwork among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Fieldwork was carried out in Jordan between 2015 and 2017, and can be divided into three distinct phases: 1) Identifying the problem to solve for; 2) Developing a solution concept; and 3) Testing the solution prototype.

1. Identifying the Problem to Solve for

To begin with, ReD’s client needed to identify a key problem to solve for. In short, they needed to know: Who should this solution focus on? Who would benefit most from an innovative education solution? Should it have a digital component? Also, given that the research would take place in Jordan, what were the social, cultural, and political levers to pull and constraints to consider there? Furthermore, what was the role of formal versus non-formal education, and what role should the client’s solution play relative to these different learning channels?

While it was not a give-in from the outset that the solution should be digital, based on conversations with our client we knew that a digital component would speak to their strategic vision for increasingly digitally-oriented product innovation. Further down the road, a digital solution would also offer greater potential to scale. However, we did not yet know what the limitations and opportunity areas around digital access and use looked like on the ground, and whether or not it would be feasible or even advisable to incorporate a digital component to the solution.

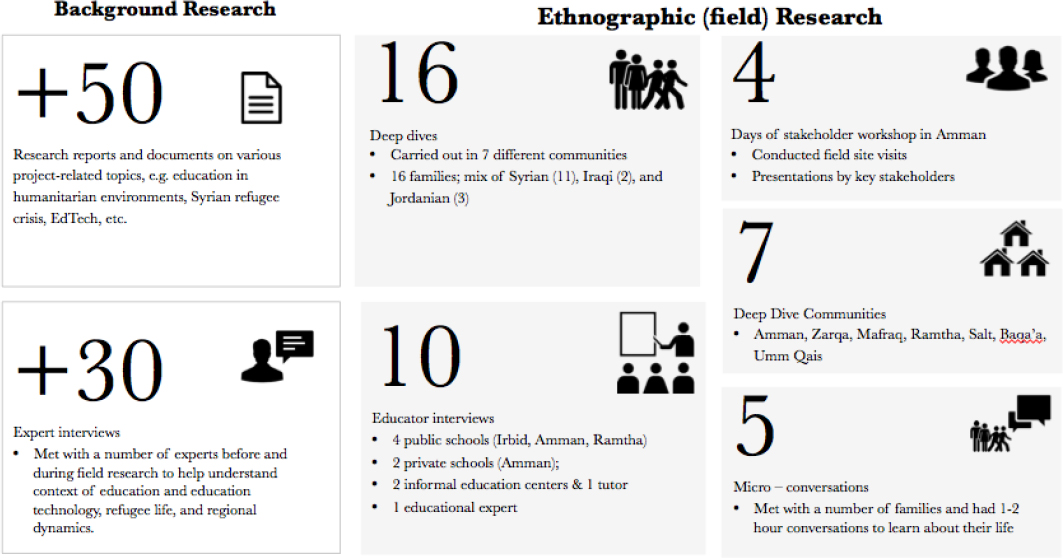

The first phase of research was, therefore, fairly open-ended. Consequently, it was also quite overwhelming. In order to develop a rich understanding of how children, caretakers, and educators engage with physical and digital educational resources in Jordan more broadly, ReD employed a mix of methods (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methods used during first phase of open-ended ethnographic research in Jordan.

Before traveling to Amman, for example, the team reached out to and interviewed many different kinds of experts – including academics, activists, and INGO workers – and carried out extensive background research on the current crisis. Once in Jordan, they teamed up with local co-researchers and translators familiar with the refugee space in order to carry out “deep dives” into the lives of 16 different families (11 Syrian, 2 Iraqi, and 3 Jordanian), as well as interviews and informal chats at local public, private, and non-formal schools, community centers, and non-governmental organizations.

To ensure a diversity of perspectives, deep dives cut across a range of ages, ethnic/religious groups, and education levels. The team also chose families from a range of geographical origins: of 11 Syrian families, 4 were from Homs, 3 from Daraa, 3 from Aleppo, and 1 from Damascus. They interviewed children who were out of school completely, behind in school, or attending only non-formal school (i.e. schooling that would not lead to a government-recognized diploma).

Based on this research, ReD’s team found a situation in which many different structural barriers impede refugee children from receiving the education they need: schools and resources in Jordan are under tremendous strain, there are not enough physical spaces for children to learn in, teachers are overwhelmed and underpaid, not to mention ill-equipped to deal with children coming from a context of trauma and PTSD, parents often cannot afford school supplies or transportation for their children to get to/from schools, bullying is rampant, and the list goes on. As one 12-year-old Kurdish refugee boy from Aleppo told us, “Every day I have to be careful when I go to school – today these kids threw stones at me, they called me ‘Syrian.’ I was with my neighbors who carried sticks to defend me.” Clearly, the client could not solve all of these problems at once.

Figure 2. Syrian refugee father walking his sons to school in Amman to ensure their safety and prevent bullying. Photograph by the author.

What ReD did first for the client, then, was to define the problem space as the critical first step in developing a strong education solution. In particular, the decision as to whether the client should focus on helping children who were already out of school (roughly 30% of refugee children aged 6-11 and 50% of those aged 12-17 in Jordan) or those at risk of dropping out was critical to the solution design.

After exploring potential solutions that could target older or younger out-of-school children, ReD saw too many barriers to solving for this challenge. For one, reaching out-of-school children would require working largely outside the formal school system, which is politically and logistically complicated. Recent guidance from Jordan’s Ministry of Education (MoE) suggested that it would be difficult for any new non-formal educational solutions to gain approval and support. Furthermore, the development of UNICEF’s well-known Makani program, a massive initiative designed to deliver informal education to out-of-school children, meant that despite the uncertain political terrain there were already significant efforts underway aiming to address this issue.

Thus, while there was no doubt that out-of-school children were perhaps those in most need of help, the challenges involved in getting these children back on track suggested that a better use of resources would be to make sure they did not leave school in the first place. Dropouts were most common for children aged 10-16 with the average age of dropout around 12 years old.1 Despite the tremendous need to help keep this group (typically referred to as the middle grades)2 in school and learning (Andrews & Harrison 2010), most interventions continue to target early elementary education or out-of-school children.

As a result of this ethnographic research, and bearing in mind the strategic capabilities of both the client and their implementing partners in Jordan, ReD settled on one key problem to solve for: Keeping children between 10-16 years old who are at risk of dropping out of school in school and learning. Not only would solving for this problem fill a critical gap by reaching those who are underserved and have a tremendous need for support, but scaling this solution to other markets has great potential. Dropouts among older refugee children is a problem in many conflict-affected settings around the world and yet there is still no major effort underway to target these children while they are still in school and help ensure that they stay in and continue learning. Naturally the content of such a solution would vary across locations and require customization, but scalability could come from the overarching model and approach.

In the short term, due to practical constraints such as budget and organizational capacity, ReD also recommended to its client that the solution first be designed for and piloted among 9-12 year olds, and that it focus on math (roughly grades 4-6 of the formal Jordanian curriculum). This would allow the client to test the solution, learn from the group, and then make iterations that it could later scale to other contexts and populations.

2. Developing a Solution Concept

Once ReD helped its client identify a key problem to solve for, the next step in the process was to aid them in answering questions more directly related to the education solution itself, namely: How could it reach children most effectively? What educational content would resonate most with the needs and motivations of children, caretakers, and educators? And which technological innovations would work, which wouldn’t, and why?

Most people around the world, when they imagine Syrian refugees, imagine them hungry and in need of shelter or medical care. Rarely do they picture them with a Smartphone in hand, WhatsApping their cousin in Daraa, where Syria’s uprising originated. This is perhaps because, as Pierre Minn (2007) argues, referring to Malkki’s (1996) work among Hutu communities, “refugees are traditionally held to the standard of an ‘exemplary victim’; they are imagined to be helpless, in need of aid, and void of particulars.”

Despite the growing academic literature on the role of technology in transforming the social and economic lives of transnational populations, very little attention has been paid to the use of technology such as mobile devices or social media among Syrian refugees. An important exception to this is the work of Wall et al (2015), which finds, based on research in one of Jordan’s major refugee camps, that cellular phones are viewed as a “crucial resource akin to food” (2) and “a vital tool for acquiring and disseminating information” (6).

ReD’s own team of anthropologists found that nearly all of the refugee households they worked with in Jordan had at least one Smartphone in their possession, if not two or more, and many also owned basic tablets and/or laptops. This included families living under roofs of corrugated tin in some of the poorest neighborhoods of Amman, as well as families renting out basic one- and two-bedroom apartments in Mafraq and Ramtha, near the border with Syria. Children as young as two and three spent much of their free time at home and “on-screen”: playing car-racing games on their parents’ phones, listening to their relatives’ voices stream in over WhatsApp from Syria and Iraq, and dancing to music videos downloaded by older siblings. “Every day, my grandfather sends me a WhatsApp voice message from Damascus, asking me if I’m doing well in school, what my grades are. I don’t tell him I’m falling behind,” one 11-year-old boy explained to us.

Figure 3. Inside a Syrian refugee home in Amman. Most households interviewed owned at least one Smartphone. Photograph by the author.

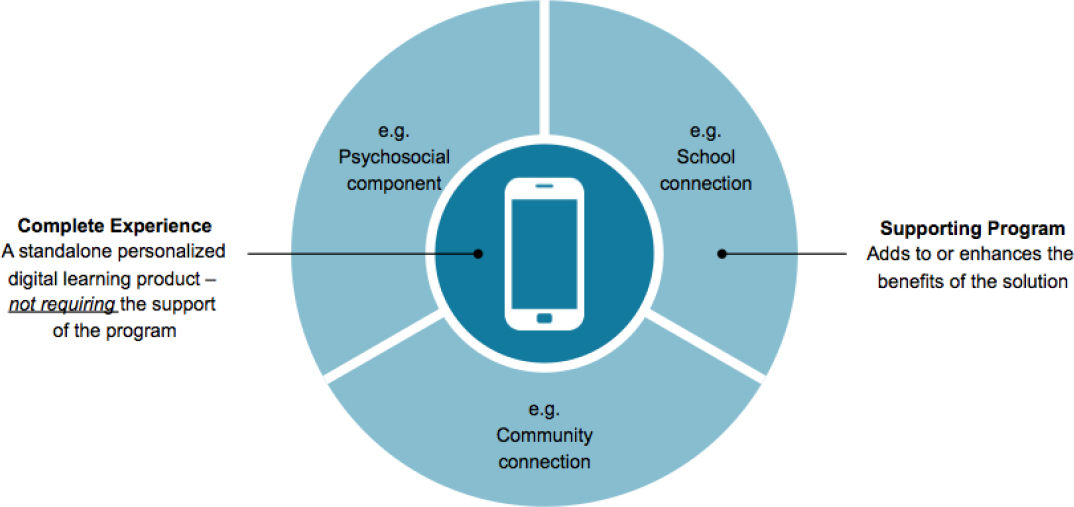

As a result of these insights, ReD recommended that its client design a standalone digital learning product that could supplement formal education and, in this way, be used both on its own in the home and as a part of supporting after-school programs (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Solution concept.

However, design constraints were significant. While most households had access to multiple devices, connectivity was a constant issue, and most of the Smartphones people owned were entry-level or older Samsung Galaxies or Nokias running on Android technology. Furthermore, as one expert on the matter told us: “There is a worry among refugees about surveillance on the part of Syria. Technology-based solutions should take this concern into account.”

Together with the client, ReD set out a plan for product development, assisting with everything from user journey mapping to solution design and product requirements. Based on its ethnographic work in Jordan, ReD was also able to guide the client in designing for culturally resonant themes, typical game behavior and preferences, device management practices, etc. By 2017, the client had built its first iteration of a mobile math-learning game designed for Android, and was ready to test it out on the ground in Jordan.

3. Testing the solution prototype

Once the client had built the solution prototype, ReD’s team returned to Jordan to test it out with children and develop a strategy for the game’s eventual hard launch. Key questions that ReD had to answer for the client at this point included: How and why were children engaging or not with the game? How did the game fit into children’s broader game and tech behavior? And what made the game a successful social experience for children?

Figure 5. Iraqi refugee children trying out the mobile learning game for math. Photograph by the author.

This time, ReD combined qualitative research—participant-observation, interviews, and focus groups (see Figure 5)—with the client’s quantitative research, namely tracking and analysis of usage patterns based on in-app diagnostic tools. While in-app diagnostics revealed larger patterns around how long and how often users played the game, as well as specific details around, for example, which junctures in the game caused users to exit most frequently, without further context it was difficult to understand why users were returning to or leaving the game. ReD’s research team therefore used the client’s quantitative data in order to guide specific areas of questioning and observation while in the field. From this, the team was able to assess both major sticking points and opportunity areas within the game, as well as develop a go-to-market strategy for it.

At the time of writing, ReD’s client is using these findings and recommendations to make changes to the prototype and drive a successful go-to-market strategy for the game’s hard launch. While it is still early to draw any definite conclusions, initial findings point to the fact that regular users of the game are already increasing their computational and geometry skills, as well as experiencing increased levels of motivation around both math and the idea of going to/continuing to go to school.

ANALYSIS OF THE PROJECT

As mentioned in the introduction to this paper, outside of camps, Syrian refugees in Jordan tend to live in precarious housing far from most official centers and aid organizations. Left largely to their own devices, they carve out channels of support and information primarily via immediate and extended kin, as well as social media. Why, then, do most educational initiatives targeting displaced populations in the region default to a standard, camp-and-center-based approach, rather than tapping into pre-existing social networks and technological access and behavior?

ReD’s team of anthropologists found that in order to best understand refugees’ daily practices and needs and therefore design effective educational initiatives for them, conducting research outside of both refugee camps and community centers was key. Ultimately, ReD’s approach and the perspective that came of it led its client to conclude that in order to most effectively reach them where they really are, educational and other initiatives targeting children affected by conflict need to shift from a standard, camp- and center-based approach and tap into pre-existing social networks and technological access and behavior.

Methods

Just driving from one neighborhood in Amman to another can take hours, and for most refugees, both public and private transportation are prohibitively expensive. As a result, many relief and refugee agencies working outside of camps provide shuttle bus and other transportation services to and from their centers.

Figure 6. Neighborhood in East Amman where many Syrian refugees live. Photograph by the author.

However, center-based programming is often an extension of the refugee camp model. Following Malkki, who in turn draws on the work of Michel Foucault (1979), the community-center approach can be viewed as one more “standardized, generalizable technology of power in the management of mass displacement” (1995: 498). Like camps, centers rely on the concentration of refugees in contained and therefore knowable, controllable spaces. Like camps, they are a means of ordering the disorder of crisis, with little attention to the ways in which refugees independently organize their lives either physically or socially.

This is not to say, however, that the work of camps and community centers is unimportant, nor that the intentions of those who work in them are misplaced. On the contrary: the need for camp and center-based services such as remedial education and psychosocial support is tremendous, and those who provide these services are often commendable and courageous in what they do.

The problem is that the standard, camp and center-based approach to refugees does not meet them where they really are. In order to develop innovative approaches that aim to reach refugees where, for the most part, they really are—outside of camps and community centers—researchers need to conduct fieldwork in refugees’ homes and communities, as well as the digital contexts they inhabit. As one political science PhD candidate working with Syrian refugees in Jordan commented during an interview with the author: “People are starting to realize that urban refugee populations are underserved and important, but NGOs often don’t have the budgets, funding, or wherewithal to work with non-camp populations. This is where companies could really add value and do something new and unique. Especially since the next wave of refugee services will be targeting urban populations around the world.”

Following this line of reasoning, ReD carried out ethnographic research among refugees living in host communities throughout northern and central Jordan. Though logistically complicated and time-consuming, in some ways it was actually easier to access urban refugees because less researchers are working with them, they are under-served, and they want to be accounted for.

Between 2015-2017, ReD’s research team spent a total of two months in Jordan conducting ethnographic fieldwork among Syrian and Iraqi refugees, as well as vulnerable Jordanians. The first and longest phase of research involved immersion into the lives of 16 families spread across 7 different cities in Jordan. With each family researchers engaged in:

- Participant-observation in people’s homes (6-8 hours per day per family, and 3+ days of immersion per family);

- Semi-structured interviews with key members of the family (e.g. parents, school-age children, children who had dropped out or were behind in school);

- Play therapy (e.g. playing games, drawing, collaging, etc.);

- Participant-authored photography and WhatsApp diaries

- Game co-design (e.g. having kids try out different physical and digital games and puzzles and then draw out themes and ideas for how a new game could be structured)

- Informal conversations with neighbors, friends, etc. who lived nearby or were otherwise a regular part of people’s daily lives.

In addition, ReD’s team met with educators from various parts of the educational world: formal and non-formal schools, public and private schools, in-home tutors, and educational experts. The team also carried out participant-observation in both formal and informal schools and learning centers. Through this ethnographic work ReD built a fuller picture of the on-the-ground learning dynamics, needs, and behaviors of children affected by conflict.

In the end, ReD’s methodological approach to the problem led its client to start thinking about an education solution in terms of something mobile – something that could be used independently from traditional brick-and-mortar structures, and that could travel with refugees as they moved from one location to the next.

Final Outcomes

Because ReD’s ethnographers conducted research outside of camps and community centers, they uncovered key findings about social networks and technology use and access in refugees’ homes/communities that ultimately shaped the client’s perspective on innovative solution development. For example, ReD found that nearly all out-of-camp Syrian and Iraqi refugee households had at least one Smartphone in their possession, if not two or more, and that digital devices served as important tools of communication and community-building among people displaced by conflict.

Based on findings such as these, ReD’s client developed an education solution that does not depend solely on camps or community centers for adoption or use (see Table 2).

Table 2. Solution outline in brief

| End-goal | To keep children aged 10-16 who are at risk of dropping out of school in school and learning. |

| Pilot target group | The pilot will take place in public schools and target 9-12 year olds. |

| Solution focus | Accelerating the target group’s academic achievement through supplementary basic math education that supports existing learning goals, while building resiliency through 21st century skills and strengthened relationships. |

| Format | A personalized, digital learning product that is engaging and relatable to children and supported by a broader program of activities and communications. |

| Solution delivery | Distributed in partnership with educators and schools burdened by a high number of refugees and vulnerable Jordanians, who do not have the resources to bring struggling students up to speed. |

| Product use-case | A personalized learning product that is promoted in schools but primarily used outside the classroom and which fosters collaboration and stronger relationships with other peers and adults. |

| Assets and roles of partners | Client will drive product design as it brings its expertise with content development, digital delivery, and developing personalized learning experiences.Local partners will drive program design, implementation, and monitoring/evaluation, as they have the on-the-ground assets and relationships in the educational space to deliver the solution. |

While it is still too early to draw conclusions on the precise impact of the solution on children’s learning, we can say that ReD’s methodological approach and the perspective that came of it led the client to think outside the box and develop an innovative digital solution that reaches Syrian refugees where they really are – outside of camps and community centers.

CONCLUSION

As is well known, the majority of Syrian refugees now residing in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey live below the poverty line, lack access to basic health care or education, and suffer from depression and discrimination, as well as serious physical and psychological trauma from the war. But refugees—like all people—also have a degree of agency in how they organize their lives and communities. And at this point they have phones, if not basic tablets and laptops. As Panagakos and Horst (2006) point out, technology helps transnational populations stay connected with their home countries, as well as forge new connections and relationships in the new locations where they live.

For organizations—be they public or private—looking to most effectively reach and impact Syrian refugee populations, they need to think not only outside the standard camp and-community-center box, but also within the dynamic social and technological networks of refugees. This is especially the case for those—like ReD and its client—who are seeking to develop innovative educational initiatives for displaced Syrian children. Whether they are in or out of school, these children, left to their own “devices” as they so often are, could be learning a whole lot more than they are now.

Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer completed her PhD in sociocultural anthropology at Yale University, where she is currently a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology. Since 2015, she has also worked as a consultant for ReD Associates in New York. Email: slb@redassocaites.com

NOTES

Acknowledgments – Thank you to Jennifer Giroux, Carine Allaf, and our Amman-based team of co-researchers and translators: Ahmad Al-Malkawi, Kholoud Barakat, Shaherah Khatatbeh, and Mohamad Sarsak. Special thanks to Killian Clarke, Emily Goldman, Erin Hayba, Dana Janbek, Vicky Kelberer, Reihaneh Mozaffari, Curt Rhodes, Denis Sullivan, Sarah Tobin, and Kate Washington for the generosity with which they shared their time and expertise. Above all, thank you to the many individuals and families in Jordan who for confidentiality reasons cannot be named but without whom this work would never have been possible. Shukran ikthir.

1. See: http://unhcr.org/FutureOfSyria/the-challenge-of-education.html.

2. Within the educational world, the middle grades typically refer to grades 4-8 (or between the ages 9-14).

REFERENCES CITED

Amnesty International.

2016. “Syria’s Refugee Crisis in Numbers.” https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/02/syrias-refugee-crisis-in-numbers/

Andrews, G. & Harrison, J.

2010. “The Middle Grades: Gateway to Dropout Prevention.” Family Impact Seminar, University of Georgia Child & Family Policy Initiative.

European Commission: Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection.

2016. “Jordan: Syria Crisis ECHO Fact Sheet.” http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/jordan_syrian_crisis_en.pdf

2016. “Lebanon: Syria Crisis ECHO Fact Sheet.”

http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/lebanon_syrian_crisis_en.pdf

2016. “Turkey: Syria Crisis ECHO Fact Sheet.”

http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/turkey_syrian_crisis_en.pdf

Foucault, Michel.

1979. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage.

Hyndman, Jennifer.

2000. Managing Displacement: Refugees and the Politics of Humanitarianism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Malkki, Liisa.

1995. “Refugees and Exile: From ‘Refugee Studies’ to the National Order of Things.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 24: 495-523.

1996. “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization.” Cultural Anthropology, 11(3): 377-404.

Minn, Pierre.

2007. “Toward an Anthropology of Humanitarianism.” The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance: Field Experience and Current Research on Humanitarian Action and Policy.

https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/51

Panagakos, AN, and Horst HA.

2006. “Return to Cyberia: Technology and the Social Worlds of Transnational Migrants. Global Networks 6(2): 109–124.

Wall, Melissa, Madeline Otis Campbell, and Dana Janbek.

2015. “Syrian Refugees and Information Precarity.” New Media & Society 1-15.