In 2022, UNICEF launched the Adolescent Girls Programme Strategy to enhance programming for adolescent girls, focusing on their well-being and empowerment. In Northern Nigeria, the Reaching and Empowering Adolescent Girls in Northwest Nigeria program was introduced in Sokoto and Katsina states. YUX conducted formative research to develop Social and Behavior Change strategies addressing harmful social and gender norms impacting girls’ education. The study found that entrenched patriarchal norms and practices such as child marriage and purdah significantly hinder girls’ educational access. Socioeconomic factors, including poverty and inadequate school facilities, further exacerbate these challenges. Girls expressed a strong desire for education to benefit both themselves and their communities. Through co-creation workshops, the girls proposed strategies like engaging fathers and community leaders to advocate for girls’ education. The resulting strategies emphasize community involvement and targeted messaging to challenge harmful norms. UNICEF Nigeria is now implementing these strategies, ensuring they reflect the girls’ needs and aspirations while promoting sustainable change. This case study details the significant value that a participatory research approach can bring to international development programming.

Context

Conducting Formative Research on Social and Gender Norms with and for Adolescent Girls

In 2022, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) developed a new vision for programming with and for adolescent girls: the Adolescent Girls Programme Strategy (AGPS) to accelerate action so girls are not left behind. Together with girls and other partners and building on its existing work, UNICEF is promoting evidence-informed, holistic action to deliver more deliberate, girl-centered programming—placing adolescent girls’ rights, well-being, voice, agency, and leadership at the very core of what it does.

UNICEF Nigeria was one of 11 initial Country Offices selected to roll out the AGPS and is implementing the Reaching and Empowering Adolescent Girls in Northwest Nigeria (REACH) programme in Sokoto and Katsina states. To support the REACH outcomes, YUX – a pan-African research and design agency – was contracted by the UNICEF Nigeria country office to conduct a formative study on the gender and social norms that affect adolescent girls in Sokoto and Katsina States. The goal of this research was to develop evidence-based Social and Behavior Change (SBC) strategies to address harmful norms impacting various aspects of adolescent girls’ lives in Northern Nigeria and to promote their empowerment. This initiative took a holistic approach, encompassing education, digital and financial inclusion, child protection and well-being, and health-seeking behavior. We aimed to understand how entrenched social and gender norms affect these areas and to create intervention plans to address them.

This case study centers on the educational experiences of adolescent girls in Nigeria, emphasizing the significant role of participatory methodologies in uncovering the norms that shape their lives. Through a participatory approach, we not only gained invaluable insights into the social and gender norms impacting these girls but also empowered them to actively contribute to the research. The case study begins with a review of existing data on the influence of these norms on education, followed by findings from our formative research. It then highlights the intervention strategies developed by the girls themselves during a co-creation workshop, showcasing the unique value of their perspectives in addressing the norms affecting their education. Finally, it presents the draft SBC strategy, curated to counter these harmful norms and promote the girls’ educational advancement.

Background: The Influence of Social and Gender Norms on the Education of Adolescent Girls in Northern Nigeria

Socio-cultural and gender norms have a significant impact on adolescent girls in the Northern region of Nigeria, shaping their behaviors, opportunities, and overall well-being. The region has a large Muslim population, and both Islamic teachings and its interpretations as well as local cultural practices play a significant role in shaping the lives of girls. One key aspect of the socio-cultural context in Northern Nigeria is the prevalence of patriarchal norms and gender inequality. Traditional gender roles often assign women and girls subordinate positions e.g., caregivers, home makers etc. within the family and society, limiting their access to education, decision-making power, and opportunities for personal and professional growth (Bolarinwa et al., 2022).

Nigeria faces a significant challenge regarding low school attendance, with approximately 10.5 million school-age children not receiving an education. This issue is particularly pronounced in the northern regions of the country, where more than half of female children lack access to schooling (UNICEF Nigeria, 2019). In Northern Nigeria, 29% of females between the ages of 15-49 are unable to read and write (National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2021). Northwestern Nigeria also holds the unfortunate distinction of having the highest rate of female illiteracy among those aged 15 to 21 in the entire country, with a staggering figure of 70.9% (Nielsen, 2021). The prevailing gender norms in Northern Nigeria contribute to this educational disparity, as communities in Northern Nigeria generally prioritize boys’ education over girls’. Girls are typically expected to prioritize domestic duties, including household chores and caregiving, while boys are encouraged to pursue education and careers (Odimegwu et al., 2017).

The prevalence of child marriage among girls in Northern Nigeria also plays a role in lower levels of education access amongst girls in Northern Nigeria. This region has one of the highest rates of child marriage in Nigeria and this has remained a significant issue despite efforts to address it. According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) in 2019, 49% of women aged 20-49 in the region were married before the age of 18 (National Population Commission, 2019). Child marriage emerges as one of the primary factors leading to these high dropout rates, as girls often find themselves forced to leave school prematurely due to this practice (Save the children, 2021).

Furthermore, Purdah, a practice observed in some Muslim and Hindu communities, entails the seclusion of women from public observation (Yusuf, 2014). This cultural and religious tradition requires women to stay out of the public eye, often by remaining within their homes or wearing clothing that covers their bodies and faces when outside. Purdah significantly limits girls’ access to education in several ways. Firstly, it often confines girls to their homes, preventing them from physically attending school and participating in a standard educational environment. Additionally, cultural norms discourage or prohibit girls from traveling alone, limiting their transportation options and making consistent school attendance difficult.

In addition, Purdah restricts access to educational resources outside the classroom. Girls miss out on opportunities to visit libraries, community centers, and other institutions that could supplement their learning. They are also less likely to engage in extracurricular activities, or social gatherings that contribute to a well-rounded education. Lastly, Purdah perpetuates a mindset that undervalues girls’ education, discouraging families from investing in their daughters’ schooling. This leads to lower enrollment rates, higher dropout rates, and limited academic achievement for girls (Yewande & Olawunmi, 2023).

Research Motivation

Given the challenging circumstances and the detrimental impact of social and gender norms on the education of adolescent girls in Northern Nigeria, there was a pressing need to further understand these norms and their effects from the girls’ own perspectives. Identifying effective Social and Behavior Change (SBC) strategies to address these harmful norms and empower adolescent girls also became crucial. In response, UNICEF Nigeria country office partnered with the YUX team to conduct formative research in Sokoto and Katsina states. The primary objective was to offer insights that would guide UNICEF Nigeria’s programming, particularly in developing strategies to support initiatives for adolescent girls. Our approach was designed to deeply understand the needs and aspirations of the adolescent girls in Northern Nigeria and to gather their perspectives on how they believe they can achieve their goals.

Research Design and Methodology

Capturing the Narratives of Adolescent Girls from Their Perspectives Using a Participatory Research Approach

The initial step in developing evidence-based Social and Behavior Change (SBC) intervention strategies to address harmful norms impacting the education of adolescent girls in Northern Nigeria was to first collect and analyze relevant evidence. Most existing literature on gender and social norms in Northern Nigeria often fails to directly engage with the girls themselves or capture their personal narratives. Therefore, it was crucial for us to ensure that we amplified the voices of these adolescent girls, providing them with the opportunity to share their stories in their own words.

In tackling the complex issues related to gender norms in Northern Nigeria, we acknowledged the importance of not only capturing the perspectives of the girls themselves but also involving them directly in the research process. Hence, we adopted a participatory research methodology, grounded in the belief that involving young women from the communities where the research was conducted would generate more insightful and meaningful results. Rather than conducting research solely for these girls, we aimed to conduct it with them, recognizing their perspectives as invaluable in shaping effective interventions. We decided to engage a cohort of 20 young women (aged 18-27) in each state as integral members of our research team. We collaborated with UNICEF Nigeria to enlist these young women. Prior to them being fully integrated into our research team, we conducted interactive training sessions in both English and Hausa (the native language of the regions). These sessions included skill-building in Human-Centered Design (HCD), interviewing techniques, and data analysis. After the training sessions concluded, the girls were given official certificates from the YUX Academy to acknowledge their dedication and also potentially enhance their professional standing.

This approach not only equipped the 20 young women with practical skills but also positioned them as active contributors to the research process. They were not just subjects of study but rather partners in designing solutions that could impact their own communities. A participatory approach also meant a more comfortable environment for the adolescent girls being interviewed and surveyed. The peer-to-peer dynamic would foster trust and openness, mitigating traditional power imbalances often present in interviewer-interviewee relationships. This environment was crucial for eliciting candid responses and deep insights into how gender norms affect their lives daily. Furthermore, by involving these young women in the research process, we ensured that the interventions and strategies developed were more relevant and reflective of their realities and aspirations. Their firsthand experiences and perspectives provided nuanced understanding, guiding the development of targeted interventions that could effectively challenge and reshape harmful social and gender norms.

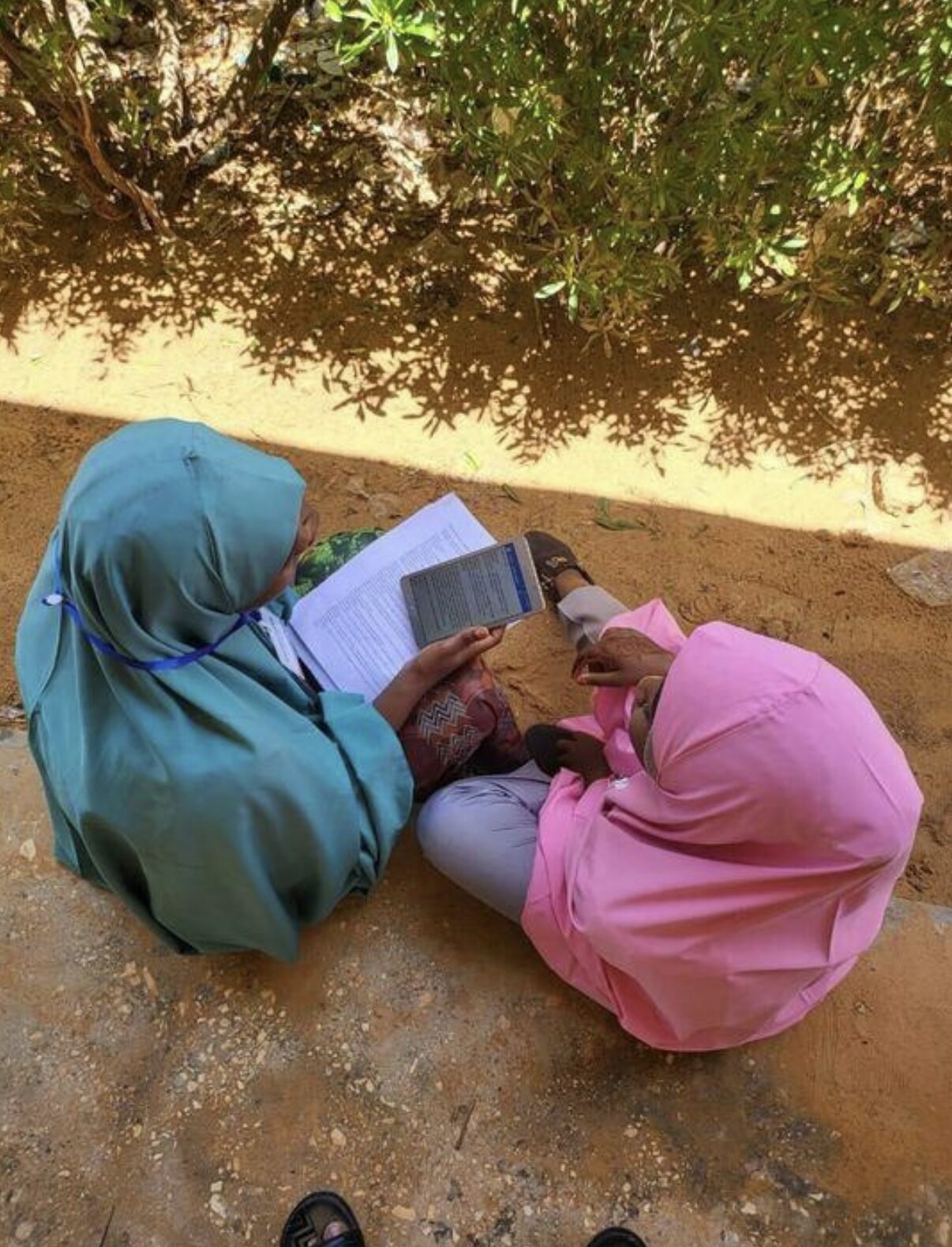

Fig 1: The young women during the training sessions

The training sessions were conducted over a single day, bringing together young women to learn and prepare for the field research they were about to undertake. For most of these young women, this training marked their first introduction to conducting research and mastering interviewing techniques. To ensure the material was accessible and relatable, it was designed in a straightforward and literal manner, drawing parallels to various aspects of their daily lives to explain the research process clearly. The sessions were conducted in their local language, Hausa, to facilitate better understanding and engagement. To create a comfortable learning environment and encourage active participation, the girls were divided into smaller groups. This grouping not only made the sessions more intimate and less intimidating but also allowed the participants to ask more questions and engage in discussions freely. Additionally, pilot studies were conducted to provide practical experience and reinforce the training. These pilots enabled the young women to apply what they had learned in a real-world context, further building their confidence and skills in conducting research and interviews.

Before going into the field, we started off the initial phase of our formative research by conducting a literature review to assess existing data and understand the current landscape regarding harmful social and gender norms affecting the education of adolescent girls in Northern Nigeria. This review helped us identify gaps in the literature, which informed the development of our questions for both quantitative and qualitative research. Additionally, we interviewed six key stakeholders from various teams within UNICEF to gain a clearer understanding of the organization’s goals and their implications.

With this preliminary data in hand, we prepared for fieldwork by drafting discussion guides and survey questions, planning logistics, identifying locations for speaking with adolescent girls, and training the 20 young women who would be part of our research team. We presented the initial drafts of the discussion guides and survey questions to our young women researchers, collaborating with them to refine the questions to ensure they were more appropriately tailored for their peers.

After completing our preparation, we conducted field research, beginning in Katsina state before moving on to our second planned location, Sokoto. The research commenced with a total of 20 in-depth interviews with adolescent girls (10 interviews in each state), aged 10 to 19, categorized into three groups: young adolescents (10-13), mid-adolescents (14-16), and older adolescents (17-19). To ensure a diverse range of perspectives, we interviewed girls and young women from various Local Government Areas (LGAs) in both states: Rimi and Mani in Katsina, and Dange-Shuni and Sokoto North in Sokoto. Our sample included girls from different social contexts, such as pregnant girls, young mothers, married girls, in-school girls, and out-of-school girls.

Each qualitative interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and was primarily conducted by young women researchers, with support from YUX local researchers. The interviews focused on various aspects of the girls’ lives, examining how harmful social and gender norms impact them. Additionally, the questions explored the strategies the girls believed would be effective in addressing these norms and empowering themselves.

In the qualitative interviews, we aimed to understand gender and social norms by engaging with not only the adolescent girls but also other key figures in their lives. This included parents or guardians, male siblings, traditional and community leaders, and religious figures. We conducted 8 interviews with caregivers, 4 with male siblings, and 8 with community stakeholders, including religious leaders, government officials, and community leaders. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and was conducted by YUX’s local researchers.

Once the qualitative interviews were completed, we proceeded to gather quantitative data using a survey developed in collaboration with the UNICEF team and our young women researchers. Equipped with tablets provided by UNICEF, the researchers collected responses under the guidance of YUX local researchers. The YUX team translated the survey questions into Hausa. Our young women researchers conducted the surveys in person and entered the data using SurveyCTO. We had a total of 548 responses from the adolescent girls in both states.

Through this comprehensive ethnographic approach, we integrated the voices of adolescent girls and their communities, ensuring our Social and Behavior Change (SBC) strategies were evidence-based, culturally relevant, and grounded in the lived experiences of those most affected by harmful social and gender norms. By combining qualitative and quantitative methods, we gained a deeper understanding of the issues. We began with qualitative research to capture the nuanced and contextual insights from the girls and their communities. This allowed us to design more effective quantitative surveys that were statistically relevant across the region. The qualitative phase informed our understanding, helping to tailor our questions and ensuring our quantitative data accurately reflected the complex realities on the ground. This method ensured our strategies were both informed by rich, detailed narratives and supported by robust statistical evidence, creating a comprehensive foundation for impactful SBC initiatives.

By actively involving adolescent girls and their communities in the research process, we aimed to foster a sense of ownership and empowerment among the participants. This approach was to ensure that the insights we gathered were not only accurate but also deeply reflective of the participants’ true experiences and perspectives. Engaging the community in this way would also build trust and rapport, which is crucial for gathering honest and open feedback. Furthermore, the participatory approach would help to identify and address potential biases and blind spots in the research process. The girls and their communities could highlight issues and cultural nuances that external researchers might overlook. This collaborative effort enriched our understanding and ensured that the SBC strategies we developed were not only theoretically sound but also practically feasible and culturally sensitive.

Fig 2: A Young Woman Researcher Administering a Quantitative Survey to an Adolescent Girl

Facilitating Co-creation Workshops to Build SBC Strategy Drafts

Having gained a deeper understanding of the detrimental impacts of these social and gender norms through our comprehensive data analysis, we facilitated co-design workshops. These workshops provided a platform to share our findings with the girls and other stakeholders, fostering collaborative brainstorming sessions to generate ideas for interventions. We had a total of 4 workshops, 2 in Katsina state and 2 in Sokoto state. Each workshop day was broken into two parts, the main workshops which included the adolescent girls and the second workshop which included the other stakeholders.

Each workshop grouped the adolescent girls into four age-based groups, with facilitation provided by our team of young women researchers, who had received additional training in workshop facilitation prior to the sessions. While these researchers led the workshops with the girls, YUX local researchers facilitated sessions with other stakeholders, including 2 male siblings, 4 caregivers (2 male and 2 female), and 4 community stakeholders. The girls’ workshops lasted approximately 7 hours with various breaks, while the sessions with other stakeholders were 2 hours each.

The workshop processes incorporated several ethnographic tools and methods. We utilized “How Might We” (HMW) questions for brainstorming, prioritizing these questions to focus on key issues, and organized participants into groups to facilitate collaborative brainstorming. Voting on prioritized ideas empowered participants in decision-making, and concept prototyping and storyboarding were employed to visualize and refine ideas. This iterative and participatory approach allowed for rich qualitative data collection and ensured that solutions were deeply rooted in the participants’ lived experiences and cultural contexts.

Drawing insights from both the field research on norms and impacts and the creative input from the girls during the co-design workshops, we formulated Social and Behavioral Change strategies. These strategies are grounded in understanding various norms and their underlying drivers, aiming to empower adolescent girls within the community by addressing their primary concerns and aspirations. The workshops’ methods ensured that the solutions were culturally relevant, inclusive, and adaptable, aligning with ethnographic principles of participant-centered design and ongoing adaptation.

Findings

Perspectives on Education from Adolescent Girls in Northern Nigeria

The girls who were interviewed shared profound insights into the significant values they associate with attending school. They emphasized their desire to contribute positively to society, gain knowledge to support and educate their siblings and future children, and enhance their English language proficiency. Recognizing that Hausa is the widely spoken language in their community, the girls understand the value of learning and speaking English as a means to access broader educational and professional opportunities, connect with diverse cultures, and participate more fully in the global community. Additionally, they expressed the importance of understanding their rights and learning how to defend themselves effectively in society.

“When you educate a girl, it’s like you educate a whole nation”

—Out of school girl, 14 years old, Mani, Katsina

“The only way I can become a female doctor is if I go to school, I can’t learn that by staying at home”

—Out of school girl, 14 years old, Mani, Katsina

“Education allows girls to know their rights, how to defend themselves and differentiate between right and wrong”

—University student, 19 years old, Sokoto-North, Sokoto

However, the influence of societal gender norms was evident in how the girls perceived the importance of education. The societal emphasis on domestic roles for women shaped their views, leading them to see schooling as essential for becoming better sisters, wives, and mothers. Some of the girls viewed education as a means to learn how to manage household responsibilities more effectively and gain respect within their familial structures. As one in-school girl from Shuni, Sokoto, expressed, “When you’re educated, your husband and co-wives would respect you.” This sentiment reflects the belief that education enhances their status and authority within their homes. Similarly, an out-of-school girl from Rimi, Katsina, highlighted the practical benefits of education, stating, “I would like to go to school so I can have answers for my child when he grows up.” This perspective reflects the girls’ aspirations to be knowledgeable and capable mothers who can support their children’s development.

“When you’re educated, your husband and Co-wives would respect you”

—In-school girl, 18 years, Shuni, Sokoto

“I would like to go to school so I can have answers for my child when he grows up”

—Out of school girl, 15 years, Rimi, Katsina

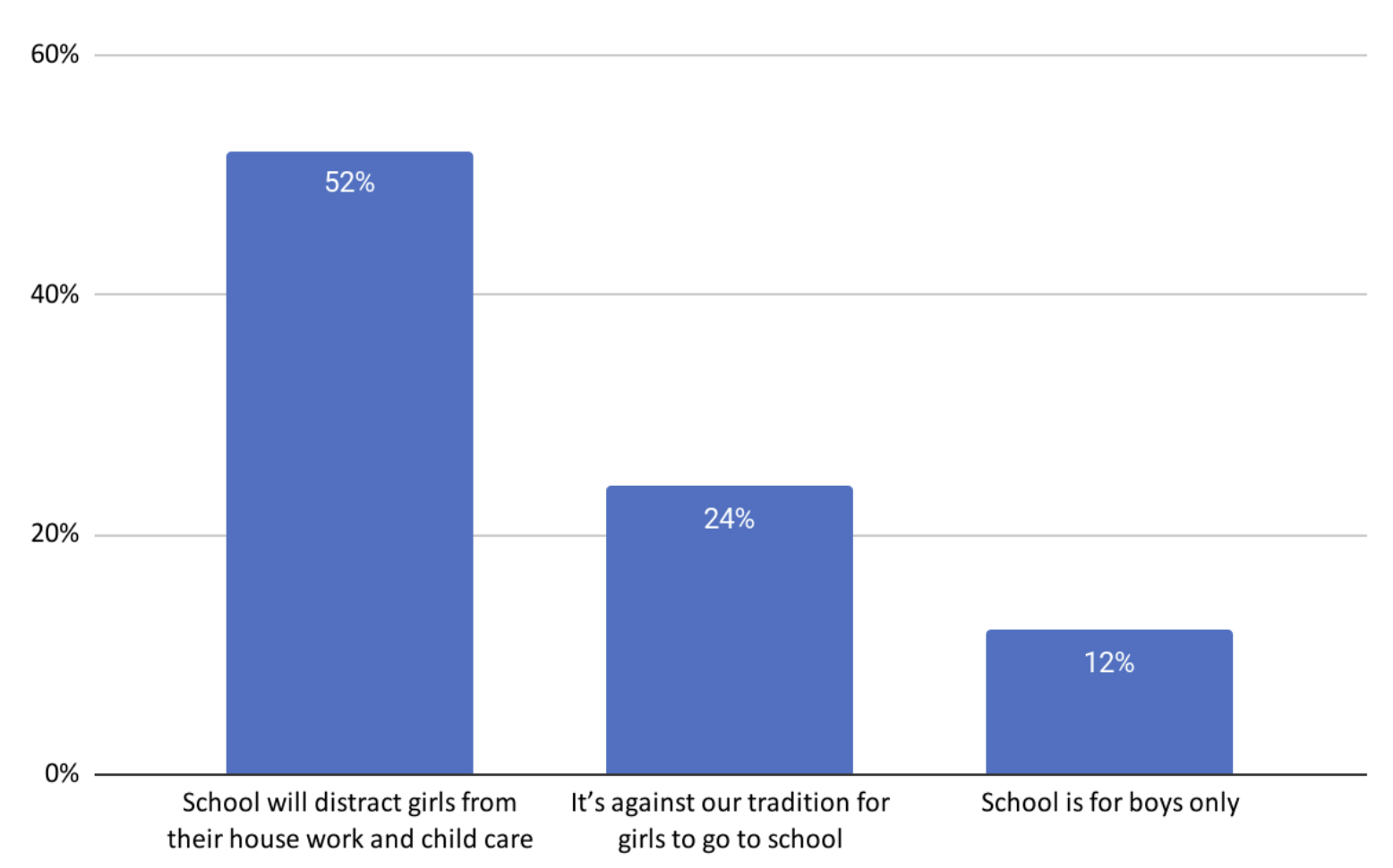

When asked about the importance of education, most of the girls stated the value of education and mentioned that they would willingly attend school if given the opportunity. However, there were still a few girls who had expressed the belief that girls’ education is unimportant. Although this viewpoint was held by a small minority, it is crucial to delve into their underlying reasons. Most of these girls viewed school attendance as an obstacle to fulfilling their domestic responsibilities and childcare duties. As a result, they showed little enthusiasm for education, prioritizing their traditional roles at home over academic pursuits. This viewpoint highlights several deep-rooted cultural and societal issues that need to be addressed to foster gender equality and promote the importance of education for all children, regardless of gender. The perception that education is secondary to domestic responsibilities and childcare duties illustrates the pervasive traditional gender roles within these communities. Girls are often expected to prioritize household chores and caregiving over their personal development and academic achievements. This expectation not only limits their immediate opportunities but also reinforces the notion that a girl’s primary value lies in her ability to manage a household and care for family members. Additionally, some girls expressed a strong preference for attending Islamiyya, an Islamic education program focused solely on teachings from the Quran. These girls often viewed formal Western education as a distraction from their religious studies. They believed that the time and effort required for Western education could detract from their commitment to Islamiyya, where they felt they gained more meaningful and culturally relevant knowledge. This perspective highlights a significant cultural divide and the value placed on religious education over Western educational models in their communities.

“I prefer to go to Islamiyya because there I will actually learn important things”

—Out of school girl, 18 years, Shuni, Sokoto

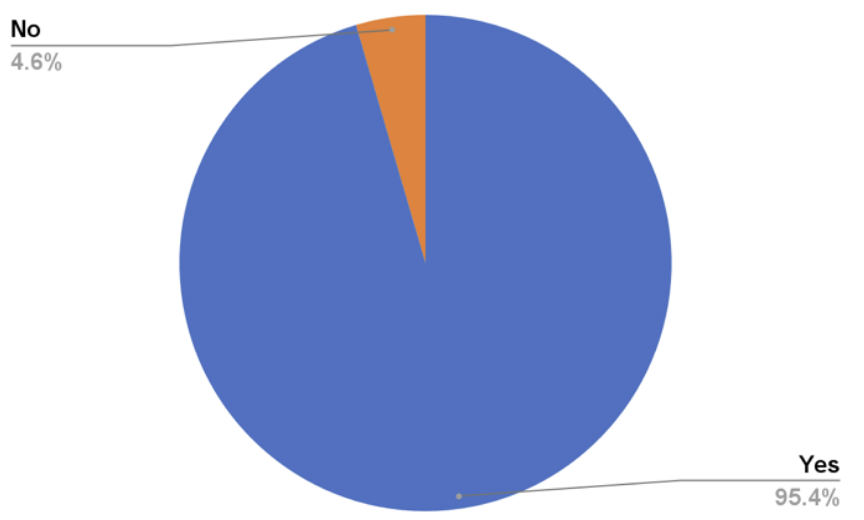

Do You Think It’s Important for Girls to Go to School?

Fig 3: Pie chart visualizing the response to: Do you think it’s important for girls to go to school? From 548 responses.

Why Do You Think School Is Not Important for Girls?

Fig 4: Why do you think school is not important for girls? From 25 responses.

Perspectives of Community Stakeholders in Northern Nigeria on Education for Adolescent Girls

Religious and cultural influences significantly shape how parents and caregivers raise their children, especially concerning gender roles and responsibilities. Islamic values and cultural norms lead to certain restrictions, such as limiting interactions between boys and girls. This limitation often prevents girls from attending schools. Furthermore, many community and religious leaders hold the belief that gender equality is fundamentally incompatible with Islamic teachings. They argue that the traditional roles and responsibilities prescribed by their interpretation of Islam do not align with contemporary notions of gender equality. As a result, these leaders often discourage the education of girls and their involvement in leadership roles within society. They emphasize that a woman’s primary responsibilities should be centered around the home and family, advocating for a more limited public role for women and girls. Additionally, education is often viewed as a gateway to girls becoming wayward or straying from traditional and cultural values. This perspective is rooted in the belief that exposure to formal education, especially Western-style education, can lead to increased independence and empowerment, which some community members fear may result in girls challenging established social norms and familial authority. This concern reflects a deep-seated apprehension about the potential for education to disrupt the traditional roles and expectations for girls within the community. This stance not only hinders the educational and professional opportunities available to girls but also reinforces existing gender norms that restrict their participation in broader societal activities.

“I believe that modern education is a shortcut to girls being wayward”

—Community leader, 42yrs, Rimi, Katsina

“Girls should never go out without their parents’ consent…but boys can go out whenever they want.. It’s a religious practice”

—Civil Servant, 50yrs, Rimi, Katsina

Fear and parental vigilance also plays a crucial role in guiding parents’ decisions on raising their daughters. Many parents, during interviews, expressed concern about potential harm their daughters might face, leading them to isolate their daughters from society and restrict their freedom. Interviews revealed a pronounced gender disparity in this parental vigilance. Parents showed heightened concern and protectiveness toward their daughters compared to their sons. This disparity was particularly evident in monitoring their children’s social circles, focusing on girls’ friendships. This level of oversight often had detrimental effects on the girls, with some parents even admitting to preventing their daughters from attending school. Their rationale for such actions was firstly to shield their daughters from harmful influences and to restrict their interactions with boys. Additionally, there is a general perception among parents, community, and religious leaders that exposure to education could lead to immorality and bad behavior among girls by overly exposing them to western culture, serving as a barrier that prevents them from attending school. Also, just like some of the girls, parents view formal education as a diversion from their pursuit of Islamic and Quranic studies, leading them to delay formal schooling until after completing religious education.

“Boys run errands while girls stay at home and do domestic chores. This is to protect the girls from danger”

—Business woman, 43yrs, Rimi, Katsina

“If not closely observed, children may be influenced by bad friends, especially girls”

—Civil servant, 40yrs, Sokoto North, Sokoto

“My male children attend Islamiyya and formal schools but my female children attend only Islamiyya, that’s a rule in the family”

—Farmer, 51yrs, Dange-Shuni, Sokoto

During the interviews, the male siblings shared that they often find themselves in a challenging position when confronted with gender inequality affecting their sisters. Many acknowledge the mistreatment and inequalities their sisters face and recognize these issues as significant. However, despite their awareness and concern, they often feel powerless to intervene effectively. This sense of powerlessness stems from deeply ingrained traditional norms and societal expectations that discourage men from challenging gender roles or advocating for women’s rights. These norms create barriers for male siblings, making them hesitant to speak out or take action for fear of facing social stigma, ridicule, or backlash. As a result, despite their desire to support their sisters, they often find themselves constrained by societal pressures that undermine their ability to actively promote gender equality within their families and communities.

“The problem with challenging some of these gender inequality is that parents will hate you for speaking up”

—Male Sibling, 37yrs, Mani, Katsina

Government officials and members of civil society emphasized that the lack of education is a significant challenge for girls in these communities. Empowering them through education is vital to breaking harmful cycles and enabling informed decision-making. The interviews highlighted the further need for comprehensive education, including topics like menstrual hygiene and sexual health, to protect girls from exploitation and abuse. The officials acknowledged that changing deeply ingrained norms and mindsets would be challenging. However, they noted that various government ministries have initiated programs aimed at improving education for adolescent girls in Northern Nigeria.

Improving Education Access and Retention for Adolescent Girls in Northern Nigeria: The Girls’ Perspective

In response to inquiries regarding methods to encourage girls to attend and remain in school during the interviews, a majority of the girls expressed that the initial step would involve raising awareness among their parents about the significance of education. Additional strategies mentioned by the girls during the interviews included financial sponsorship. Interestingly, some girls from Sokoto specifically pointed out that since many of the girls are compelled by their parents to engage in street vending instead of pursuing an education due to financial constraints, an effective approach to motivating girls would entail exploring alternative means of supporting their parents without sacrificing their educational opportunities, thereby mitigating the need for street hawking.

Developing Intervention Strategies

Prioritizing “How Might We” Questions for Brainstorming

Following the synthesis of data collected during the formative, the various challenges that hinder girls’ empowerment were identified. Each challenge was accompanied by corresponding “How Might We” (HMW) questions aimed at sparking innovative solutions. Afterwards, a collaborative prioritization exercise was undertaken by both the YUX and UNICEF teams to identify the most critical HMW questions. The criteria for prioritization included assessing the number of girls impacted, the potential level of impact, feasibility of solutions, and clarity of HMW questions for effective brainstorming sessions with girls during workshops. Through this process, 12 HMW questions emerged as top priorities. These questions were then presented to adolescent girls and stakeholders to guide collaborative efforts and solution development during subsequent workshops. The prioritized HMW questions were:

- HMW address caregivers’ concerns about bad company/ influence at school?

- HMW promote the importance of educating daughters to parents who currently don’t believe in it?

- HMW establish support systems and counseling services for girls who have experienced sexual violence, ensuring they receive proper care and encouragement to reintegrate into education and society?

- HMW find alternative ways to support girls’ families financially that do not require them to sacrifice their education?

- HMW address the stigma associated with adolescent pregnancy, providing support systems and resources to help girls continue their education and prevent exclusion and shame?

- HMW provide comprehensive financial education programs specifically tailored for girls?

- HMW educate girls on the importance and uses of legal identification?

- HMW provide affordable or subsidized devices to ensure that girls can access technology despite financial constraints?

- HMW design age-appropriate technology access programs that cater to younger girls, providing them with suitable devices and content while ensuring their safety in the digital world?

- HMW introduce the concept of digital cash transfers and encourage it’s use amongst girls?

- HMW introduce girls to the concept of the internet, making them more comfortable and confident in using digital tools?

- HMW encourage girls to seek medical care and allow them to be more comfortable doing so?

Enhancing Access to Education for Adolescent Girls: Interventions Suggested by the Girls

Below are some of the ideas generated by the girls during the workshop. As part of the activities, the girls sketched their ideas on cardboard, which are also presented here. Additionally, the second part of the workshop involved gathering feedback from other stakeholders on the girls’ presented and sketched ideas. The feedback received from these stakeholders is included below.

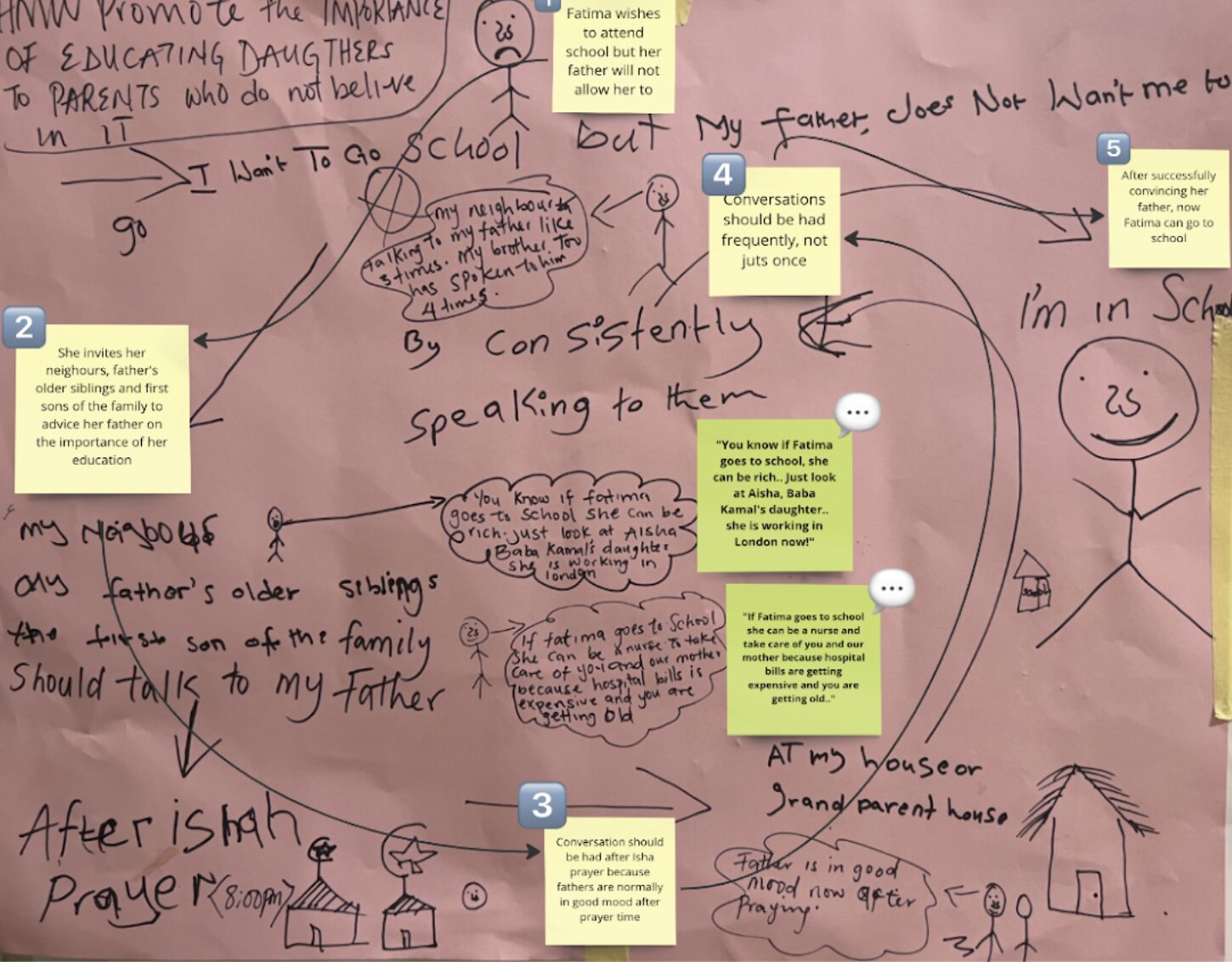

1. Advocate the Importance of Educating Daughters Specifically to Fathers

The girls in both Sokoto and Katsina conveyed the idea that in promoting the significance of educating daughters, the focus should be on engaging fathers. They recommended involving additional intermediaries like uncles, sons, and respected neighbors to provide counsel to fathers. According to the girls, since fathers typically hold leadership roles within their households, they wield the authority to permit their daughters’ school attendance. The girls also shared their perspective that fathers frequently undermine the value of educating their daughters. They also are aware of the fact that this intervention needs to be consistent as one conversation is not likely to change the fathers’ mindset. The girls also proposed that the intermediaries present the advantages fathers can gain from educating their daughters, along with a few instances of successful stories involving educated girls.

In the storyboard, the girls share a story about a young girl named Fatima who dreams of attending school. However, her father does not permit her to pursue her education. To change her father’s mind, Fatima seeks the help of her neighbors, her father’s older siblings, and the first sons of the family. These stakeholders join together to convince Fatima’s father by highlighting the benefits of education not only for Fatima but also for him. For example, one might say, “If Fatima goes to school, she can become successful and wealthy. Just look at Aisha, Baba Kamal’s daughter, who now works in London!” Another might add, “If Fatima gets an education, she can become a nurse and take care of you and our mother. Healthcare costs are rising, and as you grow older, her support will be invaluable.” They emphasize that this approach requires ongoing advocacy and consistent intervention, rather than being a one-time effort.

Fig 5: Storyboard Created by the Adolescent Girls During the Workshop

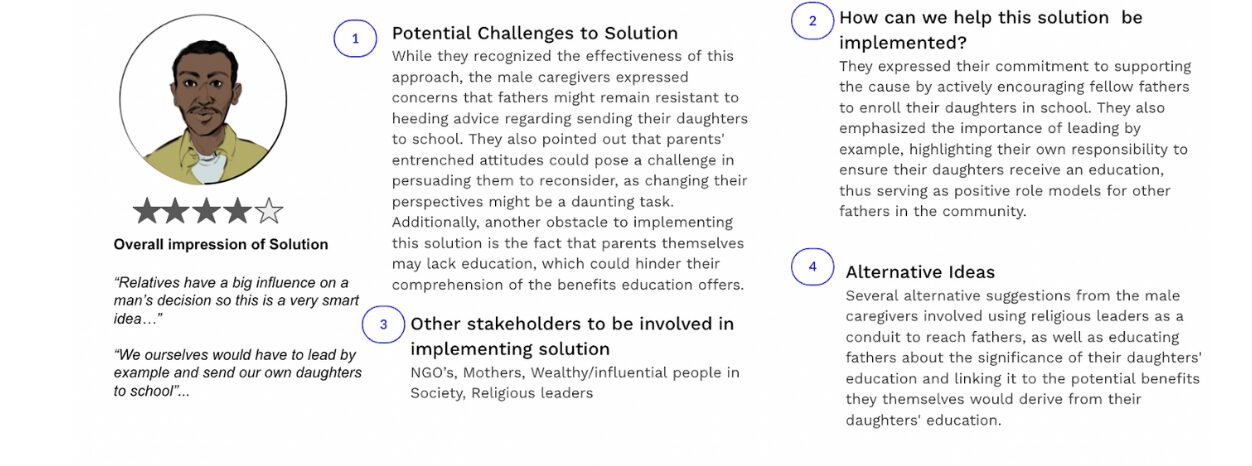

The male caregivers rate this intervention 4 out of 5, acknowledging that relatives greatly influence a man’s decision, making this approach relevant. However, they expressed concerns that some fathers might resist advice on sending their daughters to school due to entrenched attitudes and lack of education. Despite this, they committed to encouraging fellow fathers to enroll their daughters in school and emphasized leading by example. They also suggested using religious leaders to reach fathers and educating them on the personal benefits of their daughters’ education.

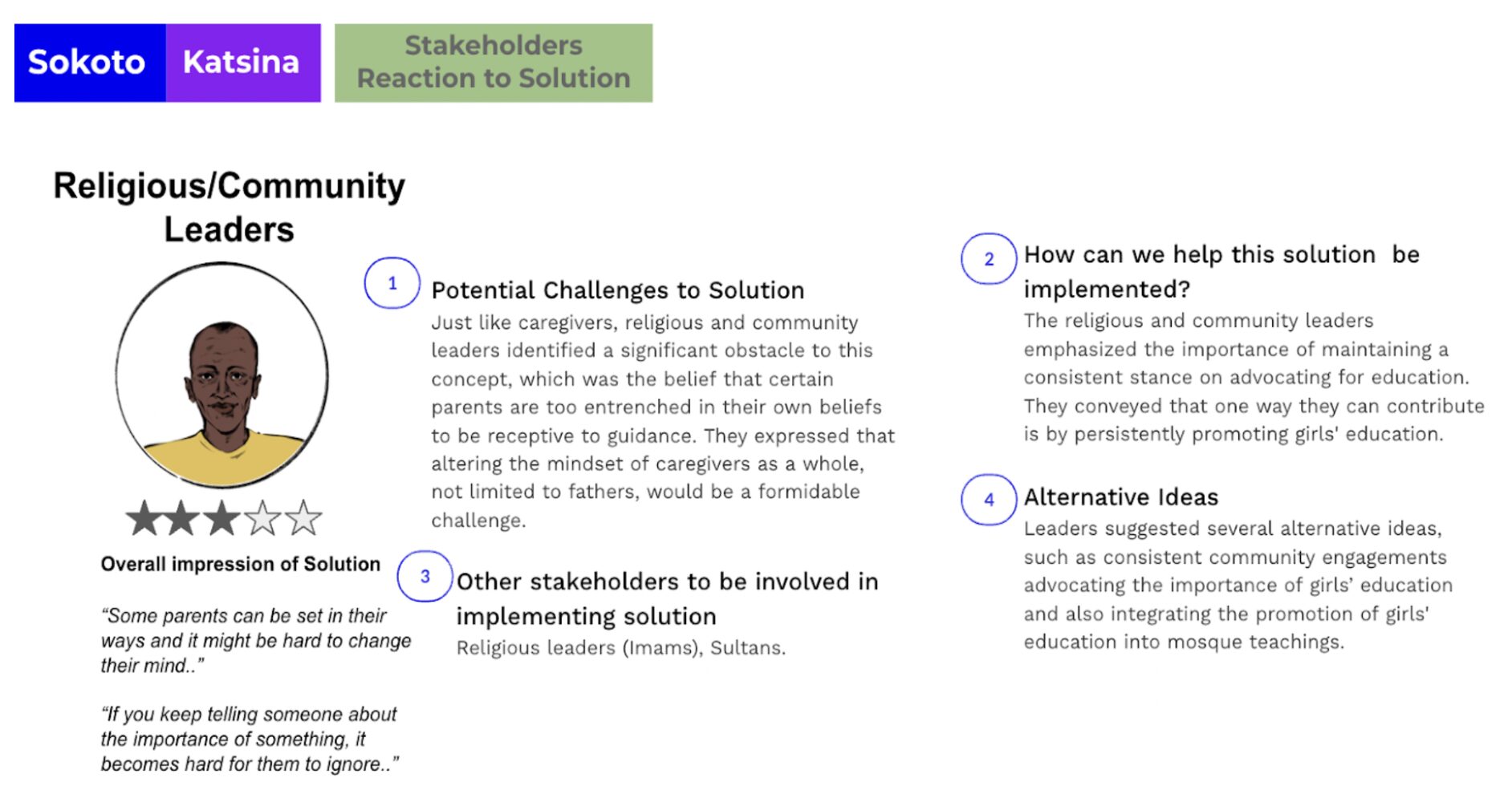

Religious leaders noted that some parents are set in their ways, making it hard to change their minds. They agreed with the girls that consistency is key. Leaders also identified a significant challenge: many parents are deeply entrenched in their beliefs. They suggested alternative approaches, such as consistent community engagements and incorporating the promotion of girls’ education into mosque teachings.

Fig 6: Perspective of Male Caregivers on the Idea provided by the Girls

Fig 7: Perspective of Religious and Community Leaders on the Idea provided by the Girls

2. Ensure Access to Free Education

The girls conveyed that economic limitations frequently lead parents to refrain from enrolling their children in school. According to them, due to conflicting financial demands, parents sometimes underestimate the significance of providing education to their daughters. As a result, the girls suggest that offering cost-free education could serve as a remedy for this issue. This approach would eliminate the need for parents to make a difficult choice between their daughters’ education and other endeavors.

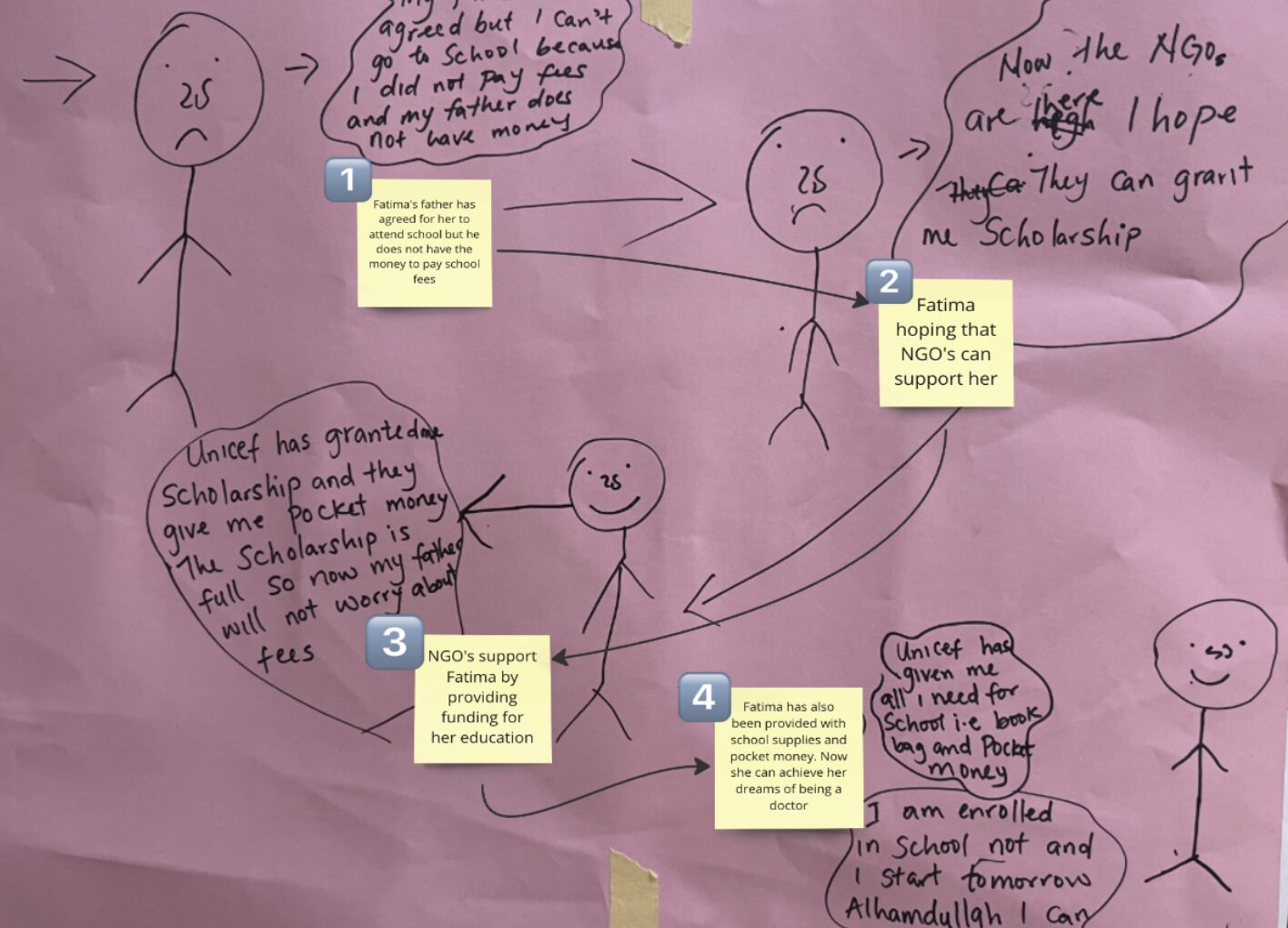

In the storyboard, the girls continue the story of Fatima, whose father initially prevented her from attending school. Now, Fatima’s father has been convinced to let her go to school, but he lacks the funds to pay for her tuition. Fortunately, Fatima receives a scholarship from NGOs and international development programs. These scholarships cover not only tuition but also school supplies and pocket money. The girls highlight that while tuition might be covered, other factors can affect a girl’s sustained education and continued enrollment, such as the lack of pocket money for transportation and food or the absence of funds for school supplies like uniforms. Recognizing this additional barrier, the girls emphasize the need for interventions to cover all aspects of a girl’s educational needs, ensuring they have everything necessary to stay in school and succeed.

Fig 8: Storyboard Created By the Adolescent Girls During the Workshop

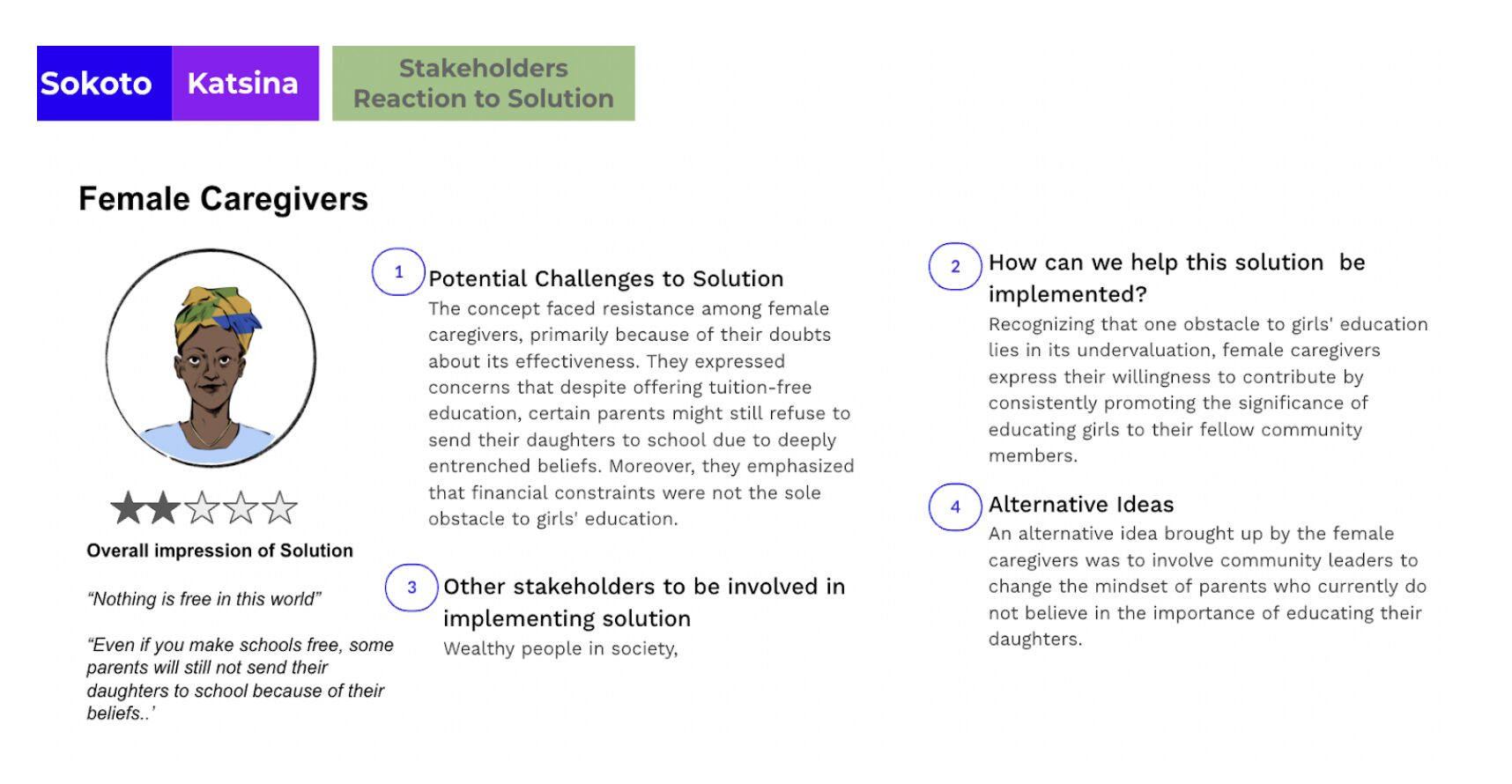

The female caregivers rated this intervention provided by the girls a 2 out of 5 and showed resistance to the concept, primarily due to doubts about its effectiveness. They voiced concerns that, despite offering tuition-free education, some parents might still refuse to send their daughters to school due to deeply entrenched beliefs. They emphasized that financial constraints were not the only obstacle to girls’ education. Acknowledging that the undervaluation of girls’ education is a significant barrier, the female caregivers expressed their willingness to help by consistently promoting its importance to their community members. They also suggested involving community leaders to help change the mindset of parents who currently do not see the value in educating their daughters.

Fig 9: Perspective of Female Caregiver on the Idea provided by the Girls

Developing Social Behavioural Change (SBC) Strategy Drafts

After concluding the workshops, the YUX team formulated drafts of Social and Behavioral Change (SBC) strategies aimed at addressing and transforming harmful social norms. These strategies were crafted using evidence-based techniques to shift collective attitudes and behaviors within the community. The strategy drafts were informed by an in-depth analysis of the social and gender norms identified through formative research. The YUX team incorporated insights gained from the workshops, where girls proposed various interventions to overcome the obstacles they faced. This participatory approach ensured that the strategies were grounded in the real experiences and suggestions of the community members.

The Socio-ecological model was also applied to the development of these strategy drafts. This model recognizes that behavior is influenced by factors at different levels, including the individual, relationship, community, societal, and policy levels. SBC strategies take this multi-level perspective into account and target interventions at various levels to address the determinants of behavior change. Understanding the broader context in which behavior occurs is crucial for the design of SBC strategies, as it ensures that interventions are comprehensive and address all relevant factors that influence behavior. Hence, each intervention has been tagged based on it’s applicable influence levels i.e interpersonal, community, services and institutions influence levels and so on.

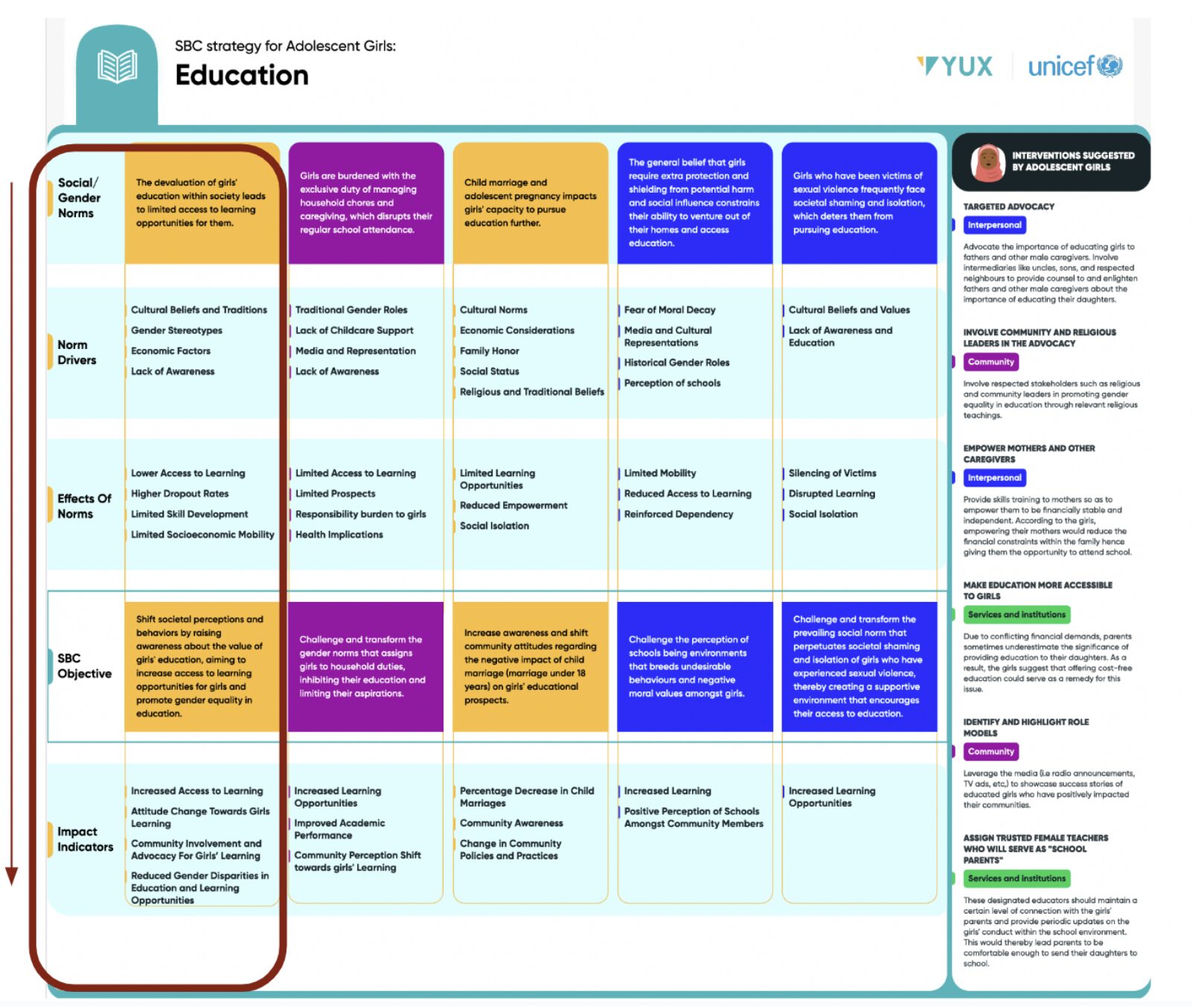

By integrating these principles of SBC, the YUX team aimed to create a comprehensive and sustainable framework for shifting harmful norms and promoting the education and empowerment of girls. The strategies were designed to be adaptable and responsive to the evolving needs and feedback of the community, ensuring their long-term effectiveness and impact. The draft outlines the specific social norms and their underlying drivers, detailing how these norms negatively affect access to education and the continued schooling of girls. It then defines the specific SBC objectives designed to counteract these harmful norms. Lastly, it includes impact indicators to measure the success of these interventions, such as increased school enrollment rates, improved attendance, and changes in community attitudes towards girls’ education.

For education, the main norms affecting the education of girls in Northern Nigeria identified include:

- The devaluation of girls’ education

- The burdening of adolescent girls with the exclusive duty of managing household chores and caregiving

- The practice of child marriage and prevalence of adolescent pregnancy

- The belief that girls require extra protection and shielding from potential harm and social influence

- The shaming and isolation of girls who have experienced sexual violence

The girls proposed several intervention strategies to enhance their enrollment and retention in education, including:

- Targeted advocacy [Interpersonal]

Advocate the importance of educating girls to fathers and other male caregivers. Involve intermediaries like uncles, sons, and respected neighbors to provide counsel to and enlighten fathers and other male caregivers about the importance of educating their daughters.

- Involve community and religious leaders in the advocacy [Community]

Involve respected stakeholders such as religious and community leaders in promoting gender equality in education through relevant religious teachings.

- Empower mothers and other caregivers [Interpersonal]

Provide skills training to mothers so as to empower them to be financially stable and independent. According to the girls, empowering their mothers would reduce the financial constraints within the family hence giving them the opportunity to attend school.

- Make education more accessible to girls [Services and institution]

Due to conflicting financial demands, parents sometimes underestimate the significance of providing education to their daughters. As a result, the girls suggest that offering cost-free education could serve as a remedy for this issue.

- Identify and highlight role models [Community]

Leverage the media (i.e radio announcements, TV ads, etc,) to showcase success stories of educated girls who have positively impacted their communities.

- Assign trusted female teachers who will serve as “school parents” [Services and institution]

These designated educators should maintain a certain level of connection with the girls’ parents and provide periodic updates on the girls’ conduct within the school environment. This would thereby lead parents to be comfortable enough to send their daughters to school.

Fig 10: Social and Behaviour Change Strategy Draft Aimed at Enhancing Access to Education for Adolescent Girls

General Learnings from a Participatory Approach

Experience and Learnings from the Field

It is important to share some of the challenges we faced as well as our general learnings from the field research. Recognizing the benefits of an iterative approach, we chose to initiate the field research in Katsina before progressing to Sokoto. The challenges and corresponding learnings from the Katsina field research informed our subsequent work in Sokoto. Some of these learnings include:

Planning Logistics Ahead of Time

While a participatory approach adds significant value to the research process, it does need a lot of planning. Coordinating the logistics on transportation and accommodation for the 20 young women who were involved in the research team was quite challenging. We were committed to ensuring the safety of these young women in the field and their secure return to their respective homes. In addition to the already nuanced situation, logistics planning was not done early due to a misunderstanding on who would be handling what. Hence, we had to figure out a lot of things just a few days before the field research was scheduled to start. Despite the stressful period for both myself and the team, we successfully managed the logistics (many thanks to the YUX local researchers: Rukayat Abdulwaheed, Balkisu Fasani, Yusuf Jamiu, and Lukman Muhammad, who were able to navigate this situation effectively and act fast!). Moving ahead to the Sokoto research, careful planning was carried out well in advance to avoid any further stress.

Involving Local Female Guides

An important lesson we learnt from the Katsina field research was the significance of including local female guides, who were well-acquainted with the community and its culture, to accompany the team in the field. The absence of these guides in Katsina posed challenges, particularly during household interviews with adolescent girls and other stakeholders. Despite the inclusion of local young women in the research team and female YUX researchers fluent in the local language, some families were hesitant to allow the research team into their homes. As a result, for the Sokoto field research, we made sure to engage local female guides, such as the daughters of village heads or community leaders, who, possessing a deep understanding of local dynamics, played a crucial role in establishing trust and rapport within households.

More Elaborate Consent Training for the Young Women on the Research Team

The young women on the research team demonstrated exceptional skills in conducting interviews and fostering comfortable environments for the adolescent girls. However, we observed a less effective consent process. Having established rapport with many of the girls being interviewed due to their familiarity with the community, the young women researchers sometimes bypassed the formal consent process. They often started conversations with the research participants before reviewing the consent material provided. To address this in the Sokoto research, we emphasized the critical importance of obtaining consent during our training, despite the researchers’ familiarity with participants. We provided practical guidance on how to effectively collect consent, ensuring that all ethical protocols were followed. Given the sensitive nature of the topics discussed, we also ensured that the young women fully grasped the interviewees’ right to withdraw consent at any point, even after the interview had started.

Choosing When to Employ a Participatory Approach

Employing a participatory approach for this project was immensely valuable. It enabled us to gather insights that would have otherwise been inaccessible through conventional methods. The young women involved in the research played a crucial role in ensuring that their perspectives and experiences were authentically represented in the findings. Their active participation not only enriched the depth of our understanding but also empowered them to advocate for meaningful change within their communities.

While this approach was valuable for this specific project context, we recognize that participatory research may not always be suitable for certain types of projects. For instance, technology assessment projects often involve specialized technical knowledge that may not be readily available within the general community participating in the research. Assessing complex technologies requires expertise that typically lies within specialized fields, making participatory methods less practical for evaluating technical specifications and functionalities.

Similarly, topics such as reproductive health or gender-based violence necessitate handling delicate conversations with sensitivity and expertise. These subjects often involve personal experiences and sensitive information that require trained professionals to ensure ethical considerations and confidentiality. Participatory research, while valuable for community engagement, may not always provide the necessary expertise and structured support required for these sensitive topics.

Furthermore, in large-scale data collection efforts aimed at national or regional levels, standardized methodologies are often preferred to ensure consistency and comparability of data across different regions or populations. Participatory approaches, which emphasize local context and community involvement, may not always align with the rigorous standards and uniformity needed for national-level data aggregation and analysis.

When engaging with important decision-makers, particularly in formal settings, the focus typically shifts towards structured presentations and formal discussions rather than participatory methods. Decision-makers often require clear, concise information presented in a manner that supports informed decision-making and policy formulation. Formal presentations and structured discussions provide a platform for detailed analysis and strategic planning, which may be more effective in influencing policy and decision-making processes compared to participatory approaches that emphasize community engagement and collaborative decision-making.

Considerations When Employing a Participatory Approach

Provide Elaborate Training to the Stakeholders

For this research, it was crucial to provide the young women researchers with comprehensive training to fully equip them with the necessary knowledge for fieldwork and workshop facilitation. During participatory research, stakeholders may lack expertise in research methods or subject matter, which can impact the quality of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Therefore, it is essential to ensure adequate, detailed, and well-contextualized training before starting research. Additionally, we conducted pilot research rounds before the main fieldwork to ensure the young women researchers were thoroughly prepared and equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge.

Avoid the Perception of “Tokenism”

There is a risk that participatory research processes may fall into tokenism, where the involvement of community members or stakeholders appears inclusive but fails to genuinely value their contributions or address power imbalances. Tokenism occurs when community members are superficially included to meet participation requirements without meaningfully integrating their input into decision-making. This can lead to frustration and disillusionment among participants, undermining the research goals and perpetuating existing inequalities.

To avoid tokenism, it is crucial to engage stakeholders as equal collaborators throughout all phases of the research process, from project design to dissemination. This involves actively seeking their input, respecting their perspectives, and incorporating their suggestions into the research framework. For instance, in this project, girls and young women were instrumental in curating the research guide, formulating survey questions, and designing workshop activities. Their insights and experiences were essential in shaping the research approach and ensuring its relevance and benefit to their communities. Additionally, during the workshops, the girls determined UNICEF’s priorities by voting on the “How Might We” questions they deemed most critical based on their lived realities. The final decisions reflected the issues the girls identified as significant, ensuring that their voices were not only heard but also influential in guiding the project’s direction.

Moving Forward: The Impact

Moving forward, the UNICEF Nigeria team is actively considering the findings from the field research and workshops, preparing to implement the interventions developed with and for the girls. A key theme that emerged from the girls’ suggestions was the critical importance of community engagement and securing the support of influential stakeholders, including community and religious leaders. For instance, one of the workshop’s “How Might We” questions focused on encouraging fathers to prioritize their daughters’ education. The primary suggestion from the girls was to sensitize community and religious leaders who can influence parental attitudes. Consequently, efforts are now concentrated on engaging these key stakeholders to ensure the successful implementation of the strategies.

The participatory approach in NGO programming is transformative as it positions community members as active contributors rather than mere beneficiaries. By involving them directly in decision-making, NGOs ensure that their programs are tailored to the specific needs and aspirations of the people they serve. This approach fosters a sense of ownership, empowering communities with practical skills and positioning them as partners in designing solutions that impact their lives. Furthermore, participatory methods enhance transparency and accountability, building trust and mutual respect between NGOs and communities. By creating a comfortable environment that mitigates traditional power imbalances, participatory approaches encourage openness and elicit deeper insights, leading to more relevant and effective interventions. This inclusive strategy not only improves program outcomes but also strengthens the social fabric, promoting collaboration and resilience among all stakeholders. For instance, the girls involved in the research team were not just subjects of study but partners in the process. This involvement provided them with valuable skills and a sense of agency, fostering a deeper understanding of the issues they face and empowering them to contribute to solutions. Their participation also ensured that the interventions developed were more reflective of their realities and aspirations, enhancing the overall impact and sustainability of the programs.

Fig 11: Adolescent Girls in School in Katsina State

About the Author

Oluchi Audu is a design researcher at YUX design, a Pan African research and design company with a mission to create digital products and services localized to the African context. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a masters’ degree in Human Computer Interaction from Carleton University. Her interests lie in inclusive design and finding ways to make technology usable and accessible to as many people as possible. She also focuses on projects around gender norms and social behaviors that impact marginalized communities, particularly women and girls. Through her work, Oluchi aims to develop innovative strategies that promote gender equality, empower underrepresented groups, and ensure that sustainable solutions address diverse needs.

Notes

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my exceptional EPIC curator, Anni Ojajärvi, for her invaluable feedback in shaping this case study. I would also like to acknowledge the UNICEF Nigeria country office for initiating this critical project. I am very grateful to my outstanding managers, Camille Kramer Courbariaux and Yann Le Beux, for their unwavering support, and to my incredible team members—Yusuf Jamiu, Rukayat Abdulwaheed, Lukman Salihu, Azeezah Adekunle, Rajay Shah, Alexandra Aho, Adama Mbengue, Yash Chudasama, and Cumi Oyemike—whose significant contributions were instrumental in bringing this work to fruition.

References

Bolarinwa, O.A., Ahinkorah, B.O., Okyere, J. et al. (May, 2022). A Multilevel Analysis of Prevalence and Factors Associated with Female Child Marriage in Nigeria Using the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey Data. BMC Women’s Health 22(158). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01733-x

British Council (2012). Gender in Nigeria Report 2012: Improving the Lives of Girls and Women in Nigeria, Issues, Policies, Action. Second Edition. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-gender-nigeria2012.pdf

British Council (2014). Girls’ Education in Nigeria Report 2014: Issues, Influencers and Actions. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-girls-education-nigeria-report.pdf

Chukwu, O. (April, 2021). New Dangers to Girls’ Education in Northern Nigeria. https://inee.org/blog/new-dangers-girls-education-northern-nigeria

Eweniyi, G.B. & Usman, I.G. (July 2013). Perception of Parents on the Socio-Cultural, Religious and Economic Factors Affecting Girl-Child Education in the Northern Parts of Nigeria. African Research Review 7(3). https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v7i3.5

Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (October 10, 2018). The Impact of Attack on Education for Nigerian Women and Girls. https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/i-will-never-go-back-school-impact-attacks-education-nigerian-women-and-girls-summary

James, G. (2010). Socio-Cultural Context of Adolescents’ Motivation for Marriage and Childbearing in North-Western Nigeria. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 2(5): 269-275.

Mawusi Amos, P. (December 18, 2013). Parenting and Culture – Evidence from some African Communities. In Parenting in South American and African Contexts, M.L. Seild-de-Moura ed. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/56967

National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund (August, 2022). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2021, Statistical Snapshot Report. Abuja, Nigeria: National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund. https://mics-surveys-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/MICS6/West%20and%20Central%20Africa/Nigeria/2021/Snapshots/Nigeria%20MICS%202021%20Statistical%20Snapshots_English.pdf

National Population Commission (2019). Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf

Nielsen, H. (2021, September 27). Literacy in Nigeria (SDG Target 4.6). Education Articles, AWCC Scotland. education2@fawco.org

Odimegwu, C., Somefun, O.D., & Akinyemi, J. (2017). Gender Differences in the Effect of Family Structure on Educational Outcomes Among Nigerian Youth. Sage Open, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017739948

UNICEF Nigeria (2019). “Education.” https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education

Yewande, T., & Olawunmi, A. (2023). Exploring the Impact of Cultural Beliefs and Practices on Women’s Education in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Education Review Provision, 3(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.55885/jerp.v3i1.191

Yusuf, H. (January, 2014). Purdah: A Religious Practice or an Instrument of Seclusion. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 4:1, 239–245. https://www.aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_1_January_2014/23.pdf