I spend a lot of time thinking about mail. Actually, I don’t just think about it—I interview and observe people sending things, and it is actually more interesting than watching people lick stamps. As an ethnographer, I look at the overall context of the work and business processes connected to what is sent, as well as the perspectives and values of the various actors involved. These include decision makers who buy postage meters, inserters, or software solutions but may not ever use them, product users, and the people who actually care about what is sent and received.

To do something as seemingly mundane as sending documents to a client, for example, a lawyer gives instructions to her assistant, who prints the documents, organizes them and addresses the envelope, then passes to a mail room with instructions on how to send to the end recipient. And this is just a relatively common scenario; more complex interactions and processes of documentation are often involved.

On the day-to-day level (in other words, what I am paid to do), all my interviews and observations get instantiated in typical corporate fashion, influencing products, technologies and strategies, most recently our SendPro line. But lately I have been trying to gain a deeper understanding of the various infrastructures underlying how we approach developing solutions for “sending stuff.” In this, I have been drawing on the work of Leigh Star (1999, 2002), who extended the concept of infrastructure beyond a “system of substrates” such as wires and pipes. Her larger definition includes newer technologies as well as cultural and institutional structures that standardize and define actions and experience. Some of the key attributes defining infrastructure include its embeddedness in other structures and the embodiment of standards.

Star recognized that infrastructures often encode “master narratives” that reveal how knowledge is constrained, built and preserved, even when it may not fit the lived experience (for example medical forms that assume heterosexual monogamous relationships by asking a woman for her husband’s name). She called for an ethnography of infrastructure because of the way these constructions embody values and noted that a key role for ethnographers is to surface the invisible work infrastructures don’t formally embody, revealing the barriers infrastructure creates and the practices and values it excludes.

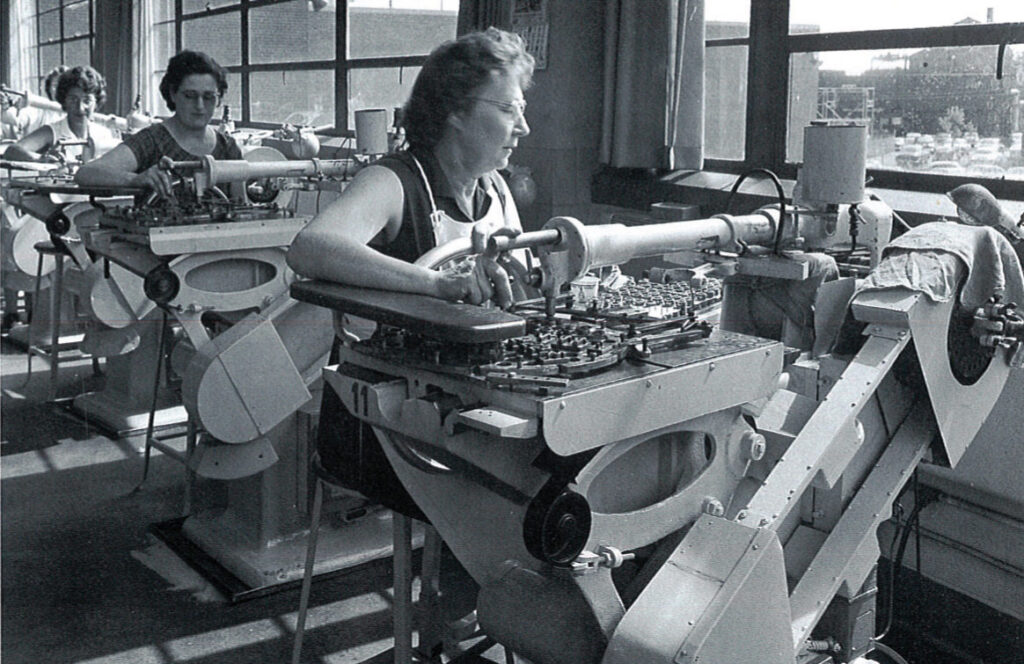

One way of looking at the products my company creates is to see them as translating infrastructures in the form of postal rules and regulations into technology. Arthur Pitney made his mark (literally) with the invention of the postage meter, a device that puts evidence of postage paid on envelopes. This bit of automation enabled the growth of a business around enabling businesses to mail things more efficiently. Nearly 100 years on, people are sending fewer letters but many more packages and parcels. Thus, our newer products provide a pipeline to private carriers such as FedEx and UPS as well as postal services in dozens of countries. Each of these carriers has their own infrastructure. To use a somewhat strained metaphor, they have each built their own rail lines, and we help people buy their tickets.

The infrastructures get complex because postal systems are highly regulated industries, as they are generally governmental organizations with all the associated rules and bureaucracy one would expect. These rules involve everything from where and how postage can be indicated, to exact sizes and weights for different rates and service classes, to required forms and rules about what can and cannot be sent. Although private carriers such as FedEx and UPS are free from much of the government regulation, they have their own rules and processes in place, which ease their logistics and help them run profitable businesses. In creating technology, we must abide not only by the rules on how things are sent, but on restrictions they place on how we can portray their products and services. Some of this is determined by their technical infrastructure—what information they put into an API. Others may be negotiated.

Yet other aspects of this infrastructure translation—how the technology is built—are determined by people, including product managers, designers, and developers, who may not “see” the choices they have because they are in turn bound by the master narratives and assumptions they have around shipping. With some time to step back from the immediacy of a product launch, I have been contemplating the implications of translating these infrastructures into software and hardware. What new master narratives do we create along the way? What assumptions are made and what opportunities are missed?

Star points out that infrastructure is most visible when it is not serving the needs of those trying to use it. A wheelchair user encountering stairs to the train platform makes obvious the assumptions about human bodies and mobility embedded in this transportation infrastructure. When it comes to sending things, the biggest barriers may in fact be the opacity of the infrastructures themselves. The current master narrative forces the users to pick which product and service they want, by name. This works well for those familiar with the infrastructure. But how many users of the United States Postal Service understand the difference between Priority and First Class mail? Or between a “flat” and “flat rate?”

These challenges are not limited to the American post; a customer in Canada noted, “I would send it by Canada Post, but with Canada Post I don’t know if I can track things.” During an office discussion we observed in Japan, one employee noted, “We always have this kind of conversation…Choosing the best solution is bothersome.” To extend my rail line analogy, our SendPro products make the process of ticket buying quicker, but if we can’t address the opacity of the infrastructure, we have lost the opportunity to improve access.

Another example speaks to the embeddedness of the infrastructure to those doing the translating. In our Beta release, several users complained about a problem in the application—they could not hide the postage on certain labels. In consulting with the developers we found out that hiding postage is not allowed for the class of mail the users had selected for those labels. Technically, the application was working properly: it was an accurate translation of the infrastructure. But functionally, it was broken because this piece of the infrastructure was tripping up users who had no understanding of a rule that excluded the choices they were trying to make. Not until this moment of failure did this aspect of the infrastructure become visible to both the translator and the user.

The issues of understanding infrastructure and rendering tacit knowledge about its master narratives explicit—to ourselves and to users—do not have easy answers. At EPIC2015, Romain and Griffin spoke of hanging out with an algorithm, and their gradual understanding of the “complex movements and negotiations of people, corporations, and materials” that were not reflected in the idealized state the technology had been coded to represent. They rightly argued for giving room in technology for the complexity of human cognition. But how do we find that space amidst the complexity of rules and regulations?

Or is our role to create room by drawing attention to how these infrastructures “shape individual actions and experiences?” (Dourish and Bell 2007). In this case, how do the various infrastructures of carrier rules, vendor tools, and workplace realities shape the every day work, and how do our creations impact that for better or for worse?

References

Dourish, P. and Bell, G.

2007 The Infrastructure of Experience and the Experience of Infrastructure: Meaning and Structure in Everyday Encounters with Space. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34: 414–430.

Romain, T. and Griffin, M.

2015 Knee Deep in the Weeds—Getting Your Hands Dirty in a Technology Organization. EPIC2015 Proceedings.

Star, L.

1999 The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43: 377–391.

2002 Infrastructure and Ethnographic Practice. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 14(2): 107–122.

Alexandra Mack is a Senior Fellow in Pitney Bowes’s Strategic Technology and Innovation Center and Treasurer of the EPIC Board. Her work is focused on developing ideas for new products, services, and technologies based on a deep understanding of work practice.

Alexandra Mack is a Senior Fellow in Pitney Bowes’s Strategic Technology and Innovation Center and Treasurer of the EPIC Board. Her work is focused on developing ideas for new products, services, and technologies based on a deep understanding of work practice.

Related

Ethnographies of Future Infrastructures, Laura Forlano

Service Infrastructures: A Call for Ethnography of Heterogeneity, Rogerio De Paula et al.

Creating Business Impact, Alexandra Mack

Policy Change inside the Enterprise: The Role of Anthropology, Alexandra Mack & Josh Kaplan

0 Comments