Public, social and community organizations are, in many locales, driving systems change toward social and economic equity and environmental justice. But their visions for what achieving systems change should look like and what it will take to realize them are as diverse as the organizations pursuing them. Organizational coalitions are spaces where diverse groups converge to negotiate their distinct transition imaginaries: “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures” (Jasanoff and Kim 2015, 153) that suggest economic, social, and natural arrangements for the common good. These negotiations aim for reaching a shared purpose and set of goals that can guide the collective efforts. However, focusing on high-level goals without contending with the diverse values and ethics that the collectives uphold can lead to a superficial and performative alignment that overshadows critical tensions, or worse, reinforcement of dominant ways of thinking that are at the root cause of the issues. As an alternative, manifesting diverse imaginaries can help uncover the diverse interpretations of futures suggested by high-level transition goals, and move beyond the dominant narratives of progress towards more radical, yet actionable transition visions.

This article proposes a design-driven collaborative sensemaking approach for manifesting the diverse transition imaginaries in emerging coalitions as a means to create more inclusive and pluralistic transition visions. We utilize narratives as a mechanism through which designers can uncover the distinct imaginaries that drive the existing initiatives, understand the tensions between the values and ethics underpinning these imaginaries, and activate alternative imaginaries in collective negotiations of transitions. We propose that, by employing discourse analysis in combination with design tools, transition practitioners can more meaningfully engage with alternative value systems and mindsets.

INTRODUCTION

In 2023, humanity experienced the hottest temperatures on record in its existence. We heard numerous calls for global cooperation, pointing to the planetary crisis that threatens the future of all species, including our own. Calls aim to radically transform our lifestyles, neighborhoods and cities, alongside the global flow of resources towards a ‘common good’. Yet, humanity does not agree on what that transformation ought to look like. Despite the apparent universal desirability of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals or comparable overarching transition objectives, social groups often have disparate visions for what achieving these goals should look like, as can be observed in their competing narratives. This diversity of interpretations of common good is often regarded as a barrier to collective action, where we aim to create a shared vision that can guide collective efforts (Kania and Kramer 2013).

However, we argue that, rather than a barrier, this diversity is a fundamental and necessary condition for forming inclusive transition coalitions, and a creative resource for envisioning alternative futures beyond the dominant norms and mindsets that govern our world. In fact, the concept of common good, with its significant influence in Western political thought is a vague and contested one (Jaede 2017). Yet this very vagueness and the constant work of defining what common good means is a fundamental condition of democratic collective action (Mouffé 2000; Mansbridge and Boot 2020). Rather than rushing to align, we invite designers and transition practitioners to engage with this contested nature of common good through diverse narratives of stakeholders, and contend with the different value systems and mindsets that social groups uphold in imagining better worlds.

We propose a practical approach for designers and transition practitioners to use narratives as part of a collaborative sensemaking process for shaping inclusive and imaginative transition initiatives. We emphasize looking at narratives as a way to account for diverse visions of common good and surface the tensions amongst these, as a way to destabilize dominant ideals of common good in favor or radical possibilities. We illustrate how this approach can be used through an example of food system transition in Chicago and, more specifically, drawing on the Design for Climate Leadership course at the Institute of Design (ID) at Illinois Institute of Technology. In this course, faculty and students facilitated a collaborative sensemaking process in the context of an emerging city-wide initiative for food waste prevention and management in Chicago. We introduced a set of tools and frameworks to identify and draw out the tensions across stakeholders’ narratives in the sensemaking process, in tandem with other design tools and methods.

In this paper, we share our experience using this approach based on the outputs of the course, as well as our lived experience, to examine the following questions:

- How can practitioners, who are working towards transformative change, use narratives for a pluralistic framing of transitions that accounts for diverse and conflicting visions of common good that social groups uphold?

- How might engaging with divergent ideas of common good promote more inclusive and creative imagination of transition pathways?

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Seeing Transitions Through Narratives

Over the past decade, we have been observing a “narrative turn” (Goodson and Gill 2011) in sustainability scholarship, acknowledging the power of narratives, and storytelling, to stabilize and destabilize public opinion, as well as inspiring new ways of thinking (Bien and Sassen, 2020; Moezzi, Janda and Rotmann, 2019; Riedy 2020). “Narratives of change” ( Dobroć, Bögel and Upham 2023; Wittmayer et al. 2019) or narrative change (ORS Impact 2021) illustrate how some interventions break the patterns of thoughts and beliefs surrounding an issue and build legitimacy around alternative pathways and imaginaries.

In the context of sustainability transitions, narratives are interpreted as meaning systems by which various stories are woven together to make sense of situations and events (Dobroć, Bögel and Upham 2023). As organizations and communities participate in the collective work of transformative change, they produce diverse narratives to frame their understanding of issues, portray visions of desirable futures, and advocate for specific pathways within the practical endeavor of the organization. They do so by purposefully making certain actors and relations visible, at the expense of others, and consequently legitimizing certain pathways as more desirable and feasible over others. Narratives take tangible forms, spanning from policy documents and impact assessments that guide large-scale initiatives, to social media postings, artistic creations and community spaces that offer glimpses into a world reimagined.

Narratives do more than represent reality, they actively construct it. And thus, they are a powerful force in how we make sense of the world around us, and envision its alternatives. Jasanoff and Kim (2015) conceptualized this as Socio-Technical Imaginaries, “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology” (153). We draw from Science and Technology Studies (STS) and critical future scholarship to consider narratives as a mechanism through which our collective visions of common good are constructed and performed as driving forces of these imaginaires.

Transition scholars utilize narratives to understand how actors form coalitions around specific imaginaries to contest the politics of transition policies, agendas and interventions (Friedrich et al. 2022, Moezzi, Janda and Rotmann 2017), and surface the controversies they involve (Baeris and Katzenbach 2021). While early research on imaginaries focused on public policy discourse and national agendas of science and technology production, a number of researchers have turned their attention beyond expert narratives to highlight local and translocal networks as spaces of resistance where alternative imaginaries are produced and performed (Chateau, Devine-Wright and Wills 2021; Dawson and Buchanan 2005). Tidwell and Tidwell (2018) state that when our collective notions of the “good life” are shaped by experts, “we are no longer looking at the ‘good life,’ but rather the ‘good’ life as perceived by a group whose perspective we are privileging above others.” (105).

We align with this view and argue that surfacing and nurturing alternative imaginaries in transition efforts is a fundamental capacity to move beyond the dominant mindsets that intentionally or unintentionally determine the rules and norms of our societies today. Seeing the world, and transitions through narratives offers a way to embrace the multitude of lived realities that shape our understandings of the world and its possibilities – as opposed to a purely positivist mindset that seeks to seeks a universal representation of reality, or bends to the “overarching politics of the real” (Inayatullah 1990). This is a call for alternative, inclusive, and pluralistic epistemologies that foreground situated understandings of the world (Haraway 1988; Paxling 2019; Suchman 2008) as opposed to a search for comprehensive and cohesive representations that the dominant view of transitions favor. As Paxling (2019) states, without changing how we produce knowledge, we risk reverting back to the normative categories that organize our understanding. Narratives, when seen as fragmented, situated and non-linear accounts of lived and dreamed realities, can provide the flexibility for new and contested meanings to emerge.

Design as a Narrative-Making Practice

Despite the growing interest in narratives, we observe a gap between their use for critical analysis of diverse claims and visions associated with transitions, and their generative application to encourage thinking and imagining beyond the dominant ideologies. In this context, the field of design occupies a significant role. The work of design is inseparable from the narrative construction of reality, and our collective imaginaries; both by shaping material arrangements that organize humanity’s collective life (Speed et al. 2019), as well as shaping the environments, processes, interfaces and tools through which we collectively learn, think and imagine.

In this sense, designers set the potential material conditions of how we make sense of the world (Krippendorff 2005; Krippendorff 2020; Tharp & Tharp, 2019), and manifest it in social, material and verbal narrative forms. Joachim Halse (2013) proposes that unlike ethnography that is traditionally interested in the present and the past, design has the potential of tangibly articulating futures we would like to see while contesting the present. With or without intent to do so, design has the influence of stabilizing and destabilizing existing imaginaries (Forlano 2019) and enabling alternative ones (Southern et al. 2014). While this capacity of design has the potential to move our thinking beyond the dominant imaginaries, it can equally solidify the dominant ways of thinking, further obscuring radical possibilities. As Sohail Inayatullah (1998) states, “the discourse we use to understand is complicit in our framing of the issue” (820). We call for an explicit recognition of the narratives through which we make sense of the world and design its possibilities, given that we can’t address today’s challenges with the same mindsets that created them.

Reclaiming the Futures with Narratives

Transition narratives, which traditionally focus on pathways and drivers, get disconnected from the lived realities of communities who have been disproportionately impacted by the negative outcomes of policy and technology agendas or rendered invisible by these. In reaction to linear development visions that “empties the future” as a set of decisions to be made, Groves (2017) highlights community-based narratives that describe “lived futures” (34). Just like archeologists constructing a picture of past worlds from their fragments, narratives, in their fragmented nature, can allow construction of alternative worlds in ways that lure imagination away from mental constraints (Baerten 2019). As opposed to dictating a unified trajectory of events, critical futures invites participants to explore multiple alternative worlds and historic trajectories through storyworlds that are anchored in daily experiences (Candy and Dunagan 2017; Howell et al. 2021; Mazé 2019).

Critical futures practitioners do so by co-creating alternative narratives of futures with communities, and centering their values and imaginaries in envisioning our collective future, through, for instance, experiential and provocative engagements or collaborative storytelling. They use narratives as a way of engaging with futures “from the inside” (Burdick 2019), in situated, subjective and provocative ways (75). These interventions aim to help participants defamiliarize with the present, engage with alternative imaginaries and challenge the dominant techno-deterministic narratives of what drives our futures. They equally highlight how mainstream visions of technological progress often overlook considerations related to gender, race, and ability; ignoring the distinct frictions that marginalized groups experience, and moreover, their agency in shaping these futures as creators and innovators (Bauman, Caldwell, Bar and Stokes 2018; Harrington, Klassen and Rankin, 2022; Tran O’Leary, Zewde, Mankoff and Rosner 2019). By drawing on this critique, we call for an increased attention to the identities, values and imaginaries of local communities; not as beneficiaries, but protagonists of transformative change.

With the practical concerns of transition practitioners in mind, we propose that accounting for the existing transition narratives, and their counter-narratives can be a way to engage with the diverse imaginaries often eclipsed by the dominant transition narratives. We argue that it is precisely at the intersections of these diverse imaginaries that we can reveal the tensions arising from different interpretations of common good, to inform a more inclusive and pluralistic framing of transition visions.

APPROACH

In this study, we propose a practical approach for contesting ideas of common good through the vantage points of different stakeholder groups in collective articulation of transition goals. We position narratives of change (Wittmayer et al. 2015) as a key mechanism through which socio-technical imaginaries are constructed and performed: solidifying specific interpretations of public matters and visions of desirable alternatives, as well as legitimizing certain pathways while marginalizing others. Unlike more objective and linear formulations of change processes, such as theories of change, seeing transitions through narratives can help us more authentically and critically engage with the messy and often controversial nature of transitions, and consider possibilities beyond the ideals, pathways and values that are reinforced by the dominant narratives.

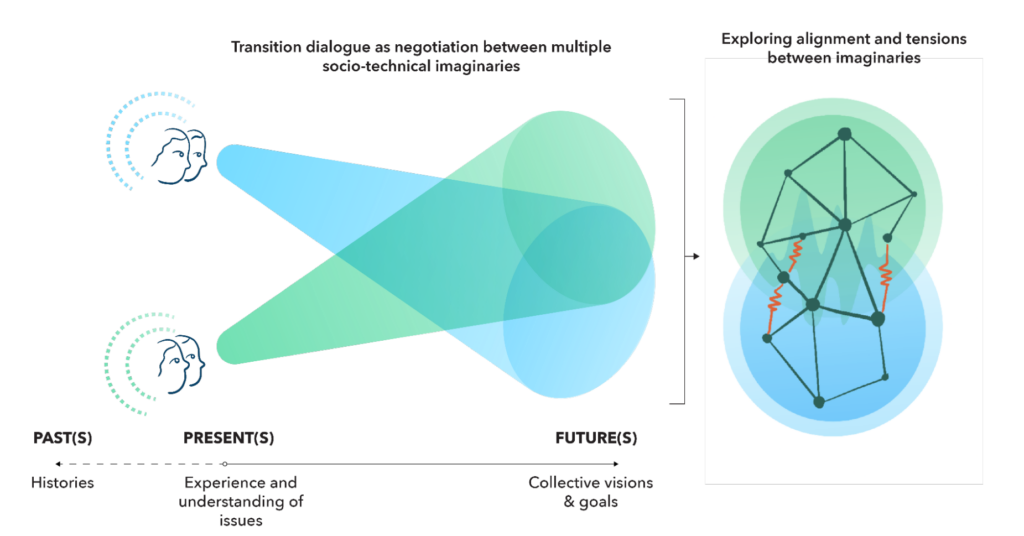

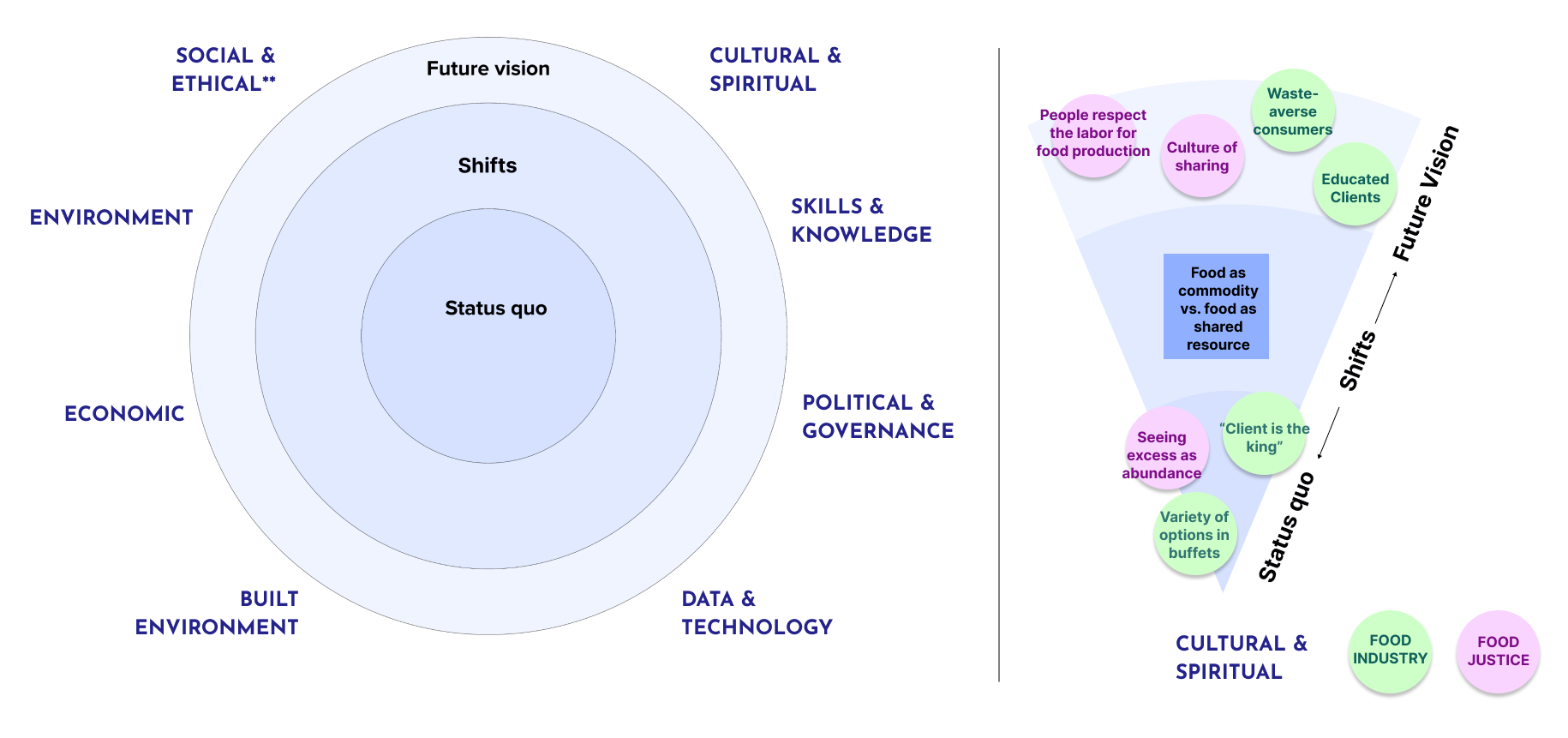

Rather than seeking to build a singular vision for different stakeholders to align on and act upon, we prioritize manifesting and working with the dissonances between these diverse ideas of common good, with the intention of better problematizing the transition itself, as we envision collaborative pathways (Figure 1). Driven by these goals, we propose a practical way for working with narratives together with ethnographic design methods to support collaborative sensemaking with stakeholder groups, in building inclusive and pluralistic transition visions.

Our methodology is grounded in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), an approach that has been widely adopted by energy and transition scholars in order to understand how distinct transition imaginaries get constructed and advocated for within policy, science and technology debates. CDA explores the social construction of the world (Gee 2014; 2017) and complex social phenomena through language as a system of representation. It differs from other discourse studies by its “constitutive problem-oriented” (Wodak and Meyer 2018) perspective, as it seeks to understand how discourse “helps to sustain and reproduce the status quo” or transform it (Fairclough and Wodak 1997, 258). CDA pays attention to power relations of class, gender, race, ethnicity and other forms of social and political identities with the intent to “root out a particular kind of delusion” (Wodak and Meyer 2018, 7). Rather than a specific method, it is founded on this critical goal that can be accomplished through a combination of methods including text-based analysis as well as other ethnographic methods.

Drawing from CDA, we prototyped a set of tools to support making sense of and constructing transition visions with diverse stakeholder groups in an inclusive and pluralistic way. These tools aim to provide a scaffolding for:

- Utilizing stakeholders’ narratives to unpack diverse interpretations of common good that shape transition imaginaries,

- Surfacing the differences in mindsets, values and worldviews beneath the overarching transition goals.

- Contending with the tensions amongst these to foster inclusive and generative transition debates.

We prototyped this approach in the context of a graduate design course where we collaborated with an emerging transition initiative for city-wide food waste management in Chicago, which involved a diverse group of stakeholders. We introduced a set of tools to uncover how different groups make sense of the issues, what values they are driven by, and what tensions they need to negotiate across their visions for the common good. Our learnings are based on the various materials that students created throughout the course project such as service maps, discussion notes, and online whiteboards. We also incorporated vignettes derived from our ethnographic observations and experience as project guides, collaborators and researchers within the Chicago food ecosystem.

SETTING THE STAGE: MAKING WASTED FOOD MATTER

As the Institute of Design project team, we had been involved with national and local wasted food research for several years, and most recently through a National Science Foundation funded research network, Multiscale RECIPES. The workshop course emerged from our ongoing conversations with organizational leads for the Chicago-based Wasted Food Action Alliance to align research and action across multiple organizations. We were asked to facilitate a collaborative sensemaking process for an emerging city-wide initiative for fighting wasted food in Chicago. This effort was in support of the City of Chicago’s participation in the Food Matters program of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The program aims to support city administrations and local partners in leveraging their collective know-how and efforts in implementing large-scale food waste management policies and programs.

Chicago is a unique place for seeing how different food futures unfold next to each other, grounded in different ideas of what makes a good food system, and “common good.” The city aspires to become the “Silicon Valley of Food” with inclusive development of its food industry (Chicagoland Food and Beverage Network, 2021), and home to a growing number of food startups. Meanwhile, it has struggled to build food security for the 20% of its population without sustained access to nutrition, specifically in South and West side communities with a predominantly Black and Latinx population that have been historically disinvested and discriminated against. But this is not a tale of abundance and scarcity. In response to the lack of access to conventional food channels, there is a flourishing community-driven food system where communities are growing, circulating, sharing and decomposing food in ways that build power, solidarity and healing. In the absence of a public infrastructure or policy for tackling food waste, it is the community groups, public schools and small-scale composters and urban farms that have been doing most of the heavy lifting for more circular food practices.

I take a break from the Chicago Food Justice Summit sessions on Zoom to join the ‘Future of Food’ webinar by Accenture that’s happening on the same day. It’s a panel of corporate executives and food innovators. When asked about what he thinks about the future of food, one of the panelists tells the story of how he had recently been welcomed with his name as soon as he stepped into a high-end restaurant. “They are caring enough to pronounce my name correctly”, he emphasizes. I look back at my notes from the conversation I attended less than an hour ago. “…radically re-imagine our food systems for each other, for our families, for our communities and beyond. […] our traditional food systems were never about access, it was about nourishing each other…” I feel torn between two realities and find myself thinking: “Are we even living in the same world here?”

– Author’s personal reflection, February 2021

We indeed live in different worlds, where food has radically different meanings, told in different stories. Having been part of these debates in Chicago for several years, we knew that any conversation for initiating collective action would have to account for the diverse realities and imaginaries and consider the diverse meanings of the ‘common good’ for the groups who have been impacted by the existing systems in radically different ways. This included contending with our own role and assumptions as researchers who are part of an academic institution. Importantly, it involves contending with researchers’ legacy of knowledge extraction and exploitation of marginalized communities across the Chicago and US, where community members express weariness about their stories being taken and re-told for someone else’s benefit (Chicago Beyond, 2019).

Course Structure

We organized the course as a platform to work with City-identified stakeholder organizations to map wasted food flows, identify current challenges for more effective management of these flows, and envision collaborative opportunities across the local food ecosystem. At the outset, our partners aimed to construct a collective vision statement and a strategic roadmap to guide the inception of a local initiative and rally stakeholder endorsement through clear and tangible steps. While recognizing the need for actionable outcomes, we explicitly advocated for a less-linear approach that sets the stage for diverse positions to be made visible, with the aim of preventing superficial consensus around a singular vision.

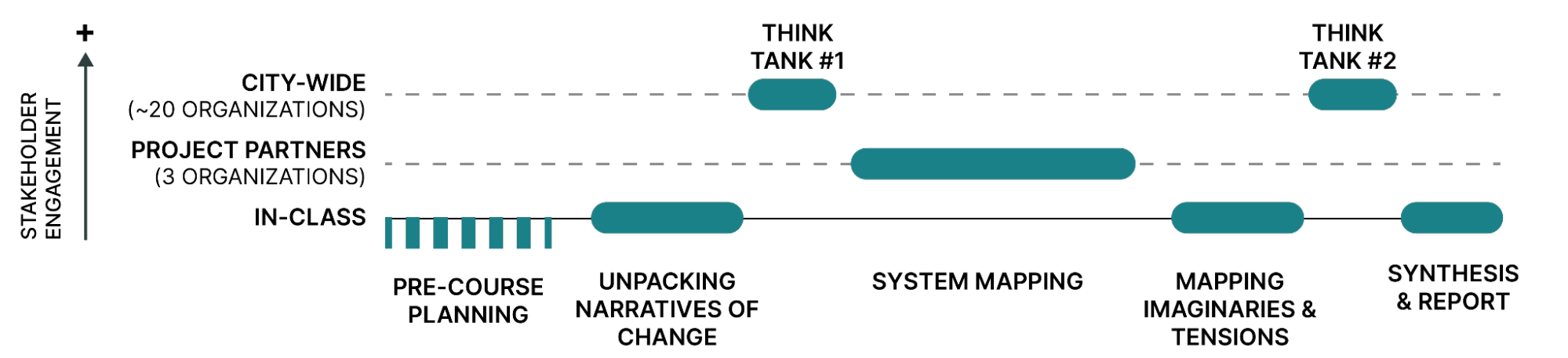

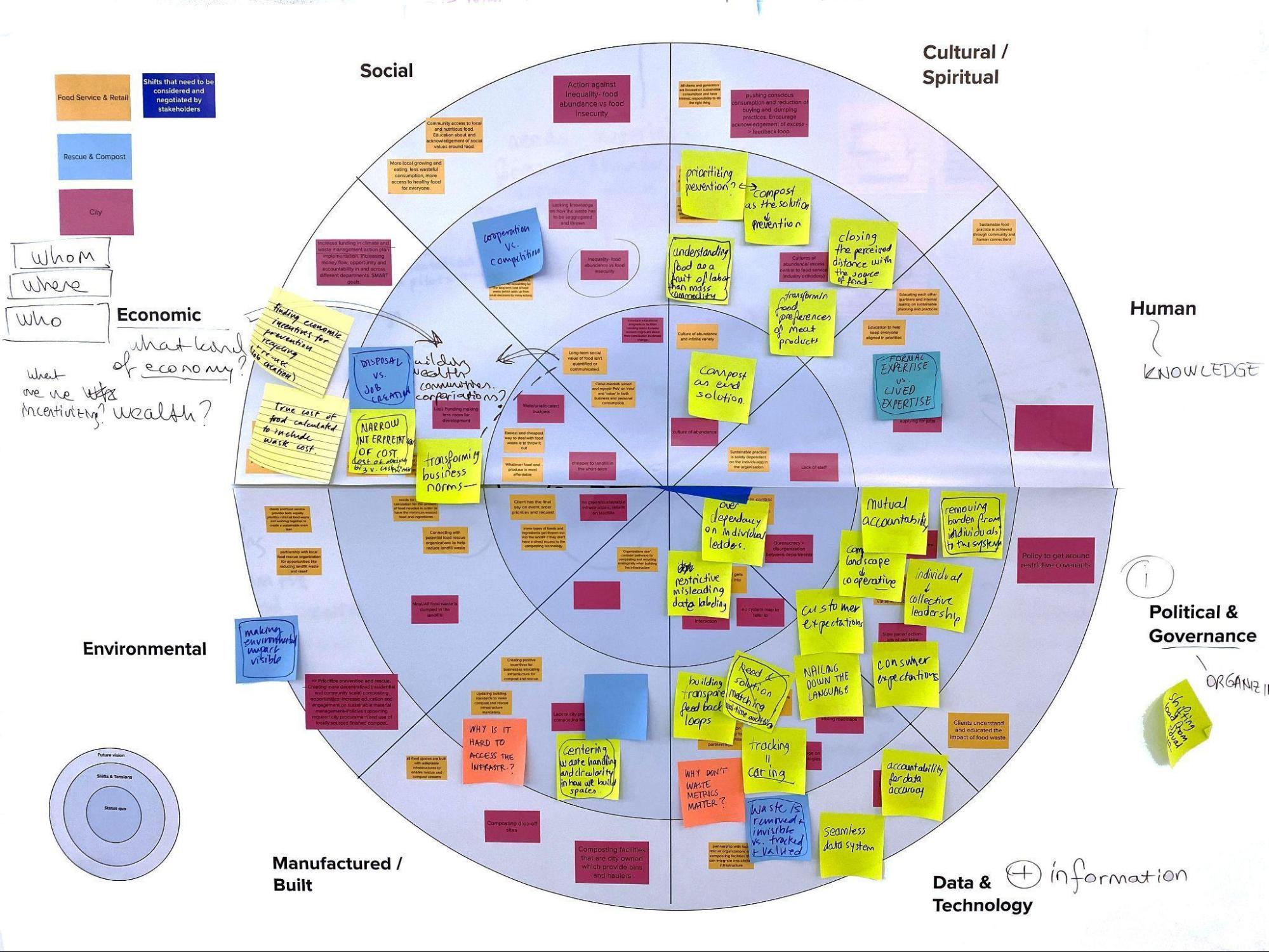

Rather than prescribing a unified vision and specific pathways, the course sought to help stakeholders see the systemic issue of food waste from each others’ vantage points both in an operational and critical sense. We adopted a pluralistic approach and aimed to re-frame the transition as a contested space at the intersection of different imaginaries of stakeholders. We structured the course as a 14-week engagement where ten graduate design students worked with three key stakeholders representing the City, food waste rescue and recycling, and food service/retail (Figure 2). Throughout the project, the students used a set of tools to analyze the narratives of stakeholders, with the goal of identifying the imaginaries that guide their efforts for creating a better food system and surfacing important shifts and tensions that need to be negotiated across these imaginaries towards a collaborative alignment. The students also used existing design tools such as service-system mapping to illustrate the material flows of food and waste across food service, rescue and processing. By doing so, we combined critical reflection on transition goals with an operational lens, grounded in different perspectives of stakeholders.

The activities included two ‘Chicago Food Matters Think Tank’ events that convened a wider group of about 30 stakeholders from public policy, food service and retail, food scrap processors and local community organizations.

Unpacking Narratives of Change

We grounded our course narrative in the proposal that there is no universal birds-eye (or God’s eye) view of a system; rather, our understanding is partial, situated and subjective. It is partial and depends on where we are looking at it from. It is situated in our own context, worldview and intent. And, it is socially constructed and subjective in that it is mutually shaped both by scientific knowledge as well as by our social and organizational realities and lived experience. We wanted to keep a distance from the idea of the all-seeing designer visualizing and taming a complex world. We initially formed four student teams, each working with a project partner to understand the issue from where they stand, making sense of these views, and constructing a patchy but shared picture.

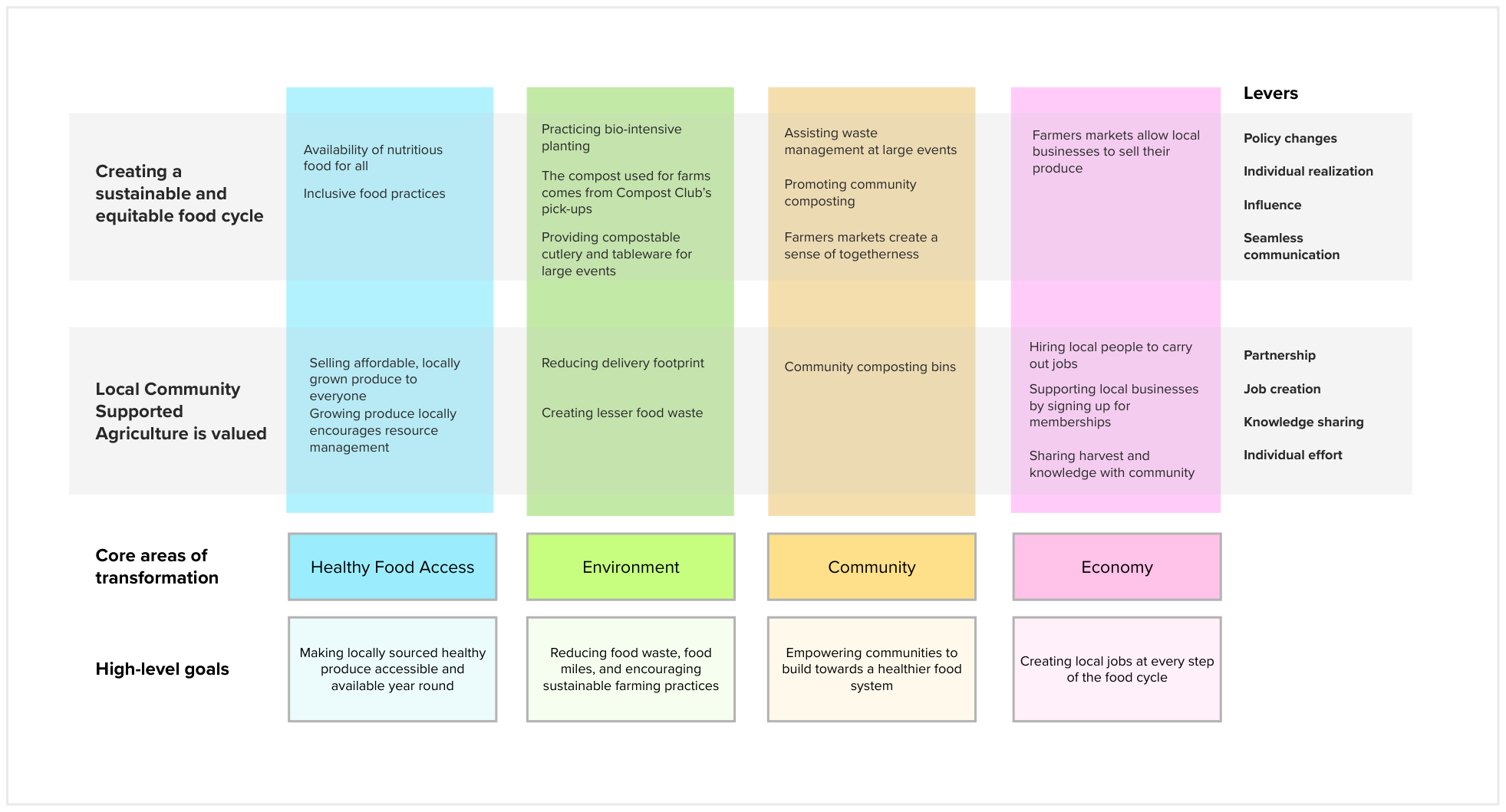

We started the project by exploring how the project partners frame their vision for transformative change in their publicly available narratives (e.g., on their websites or social media), and how they position their role within this vision. We introduced a template to help unpack the meaning of overarching transition goals (such as economic development and community empowerment) through the narratives of the different stakeholder groups. We used a dialogic approach, where this template served as a shared scaffolding between the student teams, to compare how stakeholders interpret overarching goals of the transition efforts, by focusing on where they diverge and converge. Since discourse can involve any material that joins the construction of meaning (Krippendorf 2005; Wodak and Meyer 2015), teams used a range of online sources such as websites, reports, social media pages of stakeholders to capture and unpack how each organization articulates its vision and strategy with textual and visual materials.

Doing this initial analysis exposed the team to the array of considerations based on which stakeholders relate wasted food to different aspects of a longer-term transition of the food system, and its wider implications on society. Wasted food is often articulated as an environmental concern, and an operational challenge to divert edible food and inedible scrap out of landfills. Yet, as the analysis showed, it also involves the emergence of a green technology sector and its potential to create jobs; or from a community organization perspective it concerns access to food as a human right.

But more significantly, comparing the meaning of these goals across different narratives helped us start surfacing the divergent aspirations of organizations that might be obscured by this seemingly shared transition vocabulary (e.g. economic development, sustainable food production etc.). One such term was ‘community’. We found that, city government perspective that centers urban sustainability in understanding wasted food, the term ‘community’ signifies engagement of the public and promoting social equity through expanded food access and employment. From a food industry perspective, it involves “sharing harvest and knowledge with neighbors”. And from a community organization perspective, it means empowering communities through education, spaces and organizing to foster sustainable lifestyles and community-based food production such as “equipping farmers with skills in high-tech growing” (Green Era n.d.). Not only do these imply different arguments for why ‘community’ matters in addressing wasted food, but they also suggest different levels of agency and power for the community.

We used the online narratives of four stakeholders to have an initial understanding of what matters to them in making wasted food matter, and building a dose of skepticism towards the terms through which articulate these matters, prior to our first in-person engagement with stakeholders.

Identifying Imaginaries of Wasted-food Transition in Chicago

We used the overlaps and differences between the visions of stakeholders to define three imaginaries for wasted-food transition in Chicago. These imaginaries offer distinct ways of seeing the issue, but they are not necessarily exhaustive or mutually exclusive in their considerations. Just as an organization can be a member of multiple social groups, an organization’s vision might intersect with multiple imaginaries. In defining these imaginaries, we focused on what matters organizations’ center in their vision, who they consider as the protagonists of change and what strategies they prioritize.

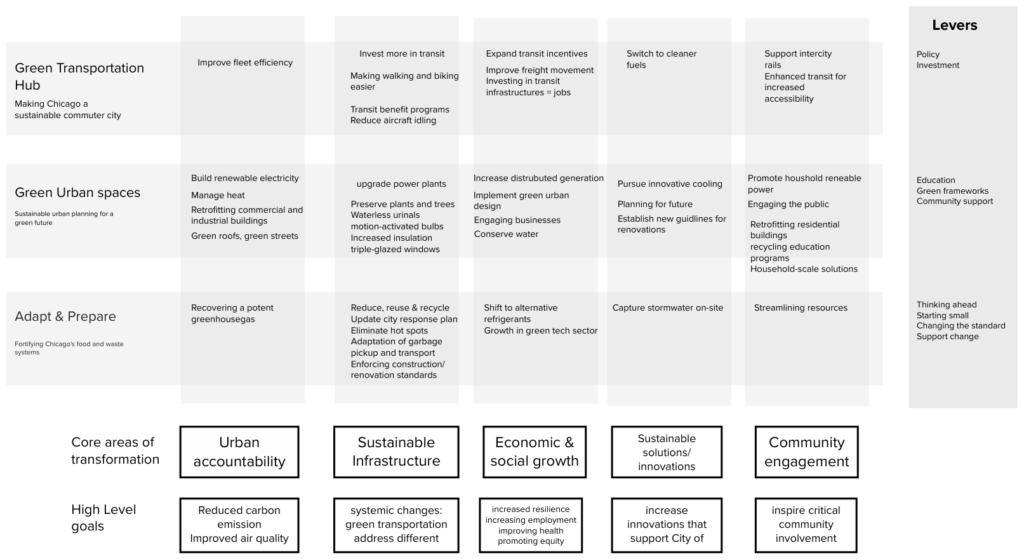

- Sustainable Cities: Centers sustainable and green urban infrastructures that are developed through citizen engagement and public-private partnerships to incentivize adoption of sustainable practices of food production and recycling and promote innovative solutions by an emerging green industry.

- Strong and Sustainable Food Industry: Centers positive environmental and social impacts of food businesses through commitment to local and sustainable food production that can create jobs for the residents and promote socially conscious consumption habits.

- Community-led Food Justice: Centers radical transformation of food systems with innovative and community-led approaches to fight racism, build economic justice and social equity by advancing hyperlocal, circular and culturally appropriate food flows.

These three imaginaries offered us an initial critical foundation and openness to diverse ways in which stakeholders might interpret current challenges and give precedence to alternatives, prior to our first contact with the wider stakeholder group. The Food Matters Think Tank event gathered 30 stakeholders at the Auburn Gresham Lifestyle Hub, a living testament to a community-driven revitalization initiative striving for a variety of healthier, sustainable, and equitable solutions for the local community. The workshop activity aimed to kickstart the project dialogue by identifying the priorities and barriers for each of policy, food rescue, recycling and community organizations stakeholder groups at the event.

A portion of the workshop discussions revolved around practical considerations for scaling implementation of existing food rescue and recycling efforts, highlighting issues like the absence of clear regulations or adequate physical infrastructure. The conversations also brought forth tensions between the prevailing mindsets and norms that characterize the current state of the food system, and the more radical visions for the future, advocated particularly by community organizations – tensions that seeded our subsequent debates. One of the workshop posters featured the phrase ‘rethink, reduce, rescue, recycle’, emphasizing the need to reconsider the system while envisioning actionable solutions as framed in the usual 3R slogan of food waste prevention.

A discernible tension concerned the need for a more collaborative environment, a priority that all stakeholders seemed to agree on – and challenged the possibility of authentic collaboration in the present competitive landscape of the food production and rescue environment. This landscape, with certain entities seeking profits from surplus food redistribution along with structural power disparities between mutual aid groups, major food banks and corporate donors, inadvertently fosters a competitive atmosphere rather than a collaborative one. The debate also highlighted the mindsets of ‘food scarcity’ and ‘charitable donation’ that perpetuate the systemic inequities, as opposed to ideas of wasted ‘abundance’ and ‘food as human right’ that are fundamental to the food sovereignty ethos of mutual aid networks.

System Mapping

In the next phase of the project, student teams collaborated with project partners to visualize their current operations in the domains of city-run organic waste management, food service & catering, and wasted food recycling. We initially developed three system maps from the operational perspectives of each project partner, which were later integrated into comprehensive visuals that depict the local service systems for food waste prevention, rescue, and recycling. These integrated maps showcased avenues for multi-stakeholder engagement across all tiers, and highlighted present issues.

However, combining an operations lens with a narrative one encouraged the teams to look beyond the issues at the surface level, and re-frame challenges considering the norms and mindsets that are constitutive of the larger problem. One such issue was the lack consciousness and knowledge of the public about the importance of food waste prevention and recycling. This is a prevalent issue in wasted food discourse, pushing consumer education campaigns to the top of food waste prevention strategies as in ReFED’s (2023). Yet, leaning onto the debate of mindsets scarcity and abundance raised in the first Think Tank event, the team challenged the notion of abundance in food service. They reframed the issue as a cultural one that “equates quality and sense of abundance with excess food” as opposed to a sense of abundance rooted in sharing as framed in community-led food justice imaginary.

Mapping Imaginaries & Tensions

While narratives of change of organizations often emphasize positive outcomes for common good, focusing only on what is deemed desirable tends to blur the lines between different positionalities that are in tension with one another. After all, both agri-corp giants and their grassroots opponents claim to build a world where none goes hungry. Imaginaries concern what their proponents are up against with respect to the status quo, as much as what they for. We prototyped an imaginaries mapping tool (Figure 5) to compare and contrast how different imaginaries problematize the status quo and what propose future alternative, in order to identify contested shifts that need to be considered and negotiated. The tool helps explore these shifts across various aspects of a systemic transition (e.g. cultural, political, data & technology etc.) based on eight capitals framework (Nogeuira, Ashton & Teixeira 2019). We mapped each imaginaries’ claims and aspirations using color-coded stickies and used the framework as a conversational aid to surface these imaginaries’ claims and counterclaims in relation to one another.

On most days, I could sense the hesitation in the class, as this meant questioning and re-creating the brief, while questioning our own belief systems and the narrative of [the] field of design itself. It often was a constant act of fostering debate while constantly hitting the breaks to try and see our own narrative and questioning the common ideals such as economic development, job creation, access that are the social impact vocabulary of many design projects. We leaned on our personal experiences, things that we were weirded about the world we live in, and the American food culture in particular with its infinite grocery stores, perfect vegetables and giant portions.

– Author’s personal reflection, March 2023

Figure 6 demonstrates how we used the tool to debate prevention of wasted food as a cultural transition, and question the norms and mindsets that perpetuate wasteful practices of production and consumption. Through a comparative analysis of how food culture is presented in the Strong and Sustainable Food Industry’s imaginary versus the Community-led Food Justice imaginary, we reframed the deeper cultural transformation as a matter of our society’s relationship with food – a contrast of seeing “food as a commodity vs. food as shared resource.” Each one of these shifts point to potential areas of generative tension where stakeholders’ visions, values and loyalties might diverge from one another, and from the dominant narrative. Yet, we preferred to phrase these as critical shifts to emphasize their role of suggesting radical pathways, rather than insurmountable conflicts. We formulated eight such dichotomous statements between the status quo and a critical systemic shift (Table 1). We then turned these into a deck of cards to support the ideation session with the stakeholders at the second Food Matters Think Tank event.

This event gathered over 30 participants from comparable stakeholder groups for a share-out and ideation session based on opportunity areas for prevention, rescue and recycling of wasted food, and the tensions between how different ideas of common good manifest themselves in these areas. The students facilitated discussions in eight break-out groups, with an opportunity area assigned to each group. As participants discussed barriers, emerging solutions and needs related to each opportunity area, we prompted them to use the deck of cards to explore the pivotal shifts that they consider significant in this endeavor. Rather than prescribing specific paths, the cards were aimed to entice conversations on longer-term impacts that need to be considered, to build legitimacy around niche interventions, and challenge norms and mindsets that our current system is founded on. We encouraged participants to openly articulate the frictions they encounter, instead of presenting well-rounded solutions.

Table 1. Critical shifts proposed in the deck of cards

| Financial | Economic | Cultural Values | Governance |

| Food waste organizations working cooperatively vs. competitively | Food scraps as waste vs. as a source of value (jobs, energy, soil) | Food as a commodity vs. food as a human right & shared resource | Responsibility of food waste mgmt is on the individual vs. on the systems |

| Data & Technology | Built Environment | Human Knowledge | Environmental Values |

| Food waste is unimportant & invisible vs. food waste is valued & tracked | Spaces designed to dispose of food scraps vs. rescue food & scraps | Valuing expertise of executives or academics vs. the expertise of the people doing the work | Not knowing the environmental impact of our food waste vs. internalized environmental costs |

Emergent Pathways

Following the event, the students synthesized the discussions into a list of opportunity areas and recommendations to inform development of a strategic pathway by our partners. The debates sparked at the event, challenged some of our previously held assumptions regarding the desirability of certain opportunity areas that we proposed and thus, led to new approaches. In addition to debates on cultural and economical paradigms that we previously discussed, two more emerged, concerning governance of collaborative efforts, and the role of data and technology.

Governance was a big question as the current landscape of food rescue and recycling in Chicago is fragmented across many grassroots efforts, without a city-wide infrastructure, or standardized process. Driven by a mindset of efficiency and seamless coordination, our opportunity areas proposed to “institutionalize and operationalize food waste prevention mindsets”. However, this received push-back from the group, on the grounds that ‘institutionalizing’ mindset perpetuated the asymmetries in power between mutual aid groups and the institutions that control access to decision-making and resources. The dominant imaginary assumed that efforts need to be institutionalized to succeed, overlooking the significance of decentralized governance from a food justice standpoint. This prompted a shift towards exploring networked yet decentralized solutions that amplify existing community-led infrastructures.

In the dominant discourse of wasted food prevention, data infrastructures are considered pivotal for scaling up food rescue and valorization, often portrayed through images of efficient industrial kitchens equipped with waste monitoring softwares. However, from a community organizing perspective, seeing the system mainly through data can render grassroots and community-based infrastructures invisible, and undermine their efficiency in responding to community needs. For instance, nearly twenty Love Fridges across Chicago neighborhoods serve as self-organized drop-off points for the mutual aid groups, while logging every delivery in pantries can be a hindrance in adhoc food rescue. This tension shifted our goal framing from more and better-quality data to flexibility and inclusivity of data-driven approaches, without shifting agency away from local groups who operate in a more relational mode.

We integrated these conversations into what we aimed to be a pluralistic synthesis, meaning, we sought to explicitly challenge the assumption of certain pathways being inherently desirable for all, as in the case of data-driven approaches. We highlighted the ongoing grassroots and community-based efforts as legitimate pathways for addressing wasted food in ways that can help shift the dominant economic and social paradigms that our wasteful food system operates from. Perhaps one of the most challenging tasks was translating a pluralistic approach into a project report in a way that is easily accessible and usable by the project partners, providing clarity without flattening the ongoing debates.

DISCUSSION

We presented a practical approach for using narratives to account for and contend with the diverse imaginaries of stakeholder groups in framing transition goals for collaborative action. We built on the recent work in transition studies, that advances narratives as a powerful mechanism to meaningfully engage with the controversial and conflictual nature of transitions, where under the seeming universality of high-level transition goals such as sustainability or equity, stakeholders portray different futures for the collective good. We introduced a set of tools in development that uses narratives for unpacking the diverse and conflictual meanings of transition goals, and building upon these divergent perspectives to challenge the dominant mindsets and norms through which transitions get framed. By explicitly engaging with narratives as tangible materials and abstract meaning systems that we design through, we were able to:

- Broaden our understanding of the transition in question, by considering it as a constellation of public matters (Latour and Weibel 2005) and aspirations extending beyond the dominant claims around the issue.

- Account for the diverse and potentially conflicting interpretations of high-level transition goals that characterize distinct imaginaries of stakeholder groups.

- Surface the tensions between the goals and pathways that different groups advocate for, and engage with these in a generative way. This enabled us to challenge our assumptions concerning the fitness and desirability of specific approaches, as well as the economic and social norms through which we frame the issues and potential pathways.

As opposed to framing transitions as a set of strategic actions orchestrated around an assumed ideal of common good, narratives offer us a way to engage with the plurality of lived and dreamed realities that shape diverse meanings of collective good. This fundamental diversity of understandings of what that common good constitutes, is a critical and creative resource to cultivate the radical shifts that our world needs. Clearly articulating the points where stakeholders’ imaginaries diverged from each other and framing these differences as specific tensions provided a foundation for cultivating pluralism by actively resisting the tendency to reconcile these differences. As Mouffé (2000) contends, pluralism acknowledges and values differences while challenging the quest for unanimity and homogeneity, which often proves to be illusory and exclusionary.

Surfacing and sustaining this divergence early on was foremost, a tactical act, as it reduced the risk of a superficial alignment that might otherwise conceal tensions stemming from stakeholders’ hidden agendas. However, this required a balancing act of making room for the differences without stifling ongoing dialogue. It was equally a political act, as it helped us identify the norms and values that are reinforced by the dominant narratives and the regimes that they sustain, which promote particular notions of common good. The challenge entailed tending to these differences without striving for immediate reconciliation, instead, allowing them to persist as the wedges that sustain open rifts, against the homogenization of perspectives within the prevailing narrative. And finally, it was a generative one, as it invited a reappraisal of the radical futures that are in the making, beyond the conventional blueprints of tackling wasted food. The “un-common good” we envision encompasses these departures from the illusory and oppressive homogeneity of commonality, embracing the richness of diverse perspectives and paving the way for transformative and inclusive shifts in our collective path forward.

LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper offered a methodological approach for using narratives to surface and work with the diverse and sometimes conflicting imaginaries of stakeholder groups with the aim of framing more inclusive and pluralistic transition visions. We would like to emphasize that the tools we prototyped here are not plug & play meaning generators, but aids for deep reflection and questioning to help practitioners navigate the intricate landscape of values and mindsets that underpin multi-stakeholder discourse, including their own.

First of all, narratives are a slippery and elusive material to work with. Meaningfully using narratives relies a lot on the group’s ability to look beyond the buzzwords, identify the nuances in the meaning and recognize the historic and political ties of specific concepts. Therefore, we suggest a certain familiarity with the specific context, as well as the larger discourse that surrounds the issue. For instance, the seemingly interchangeable concepts of ‘food waste’ and ‘wasted food’ for an unfamiliar ear, have a significant difference in that the latter emphasizes the act of wasting a valuable resource, as opposed to normalizing it as another waste stream to be handled.

Organizational discourses tie the micro-world of an organization and its reasoning to the grand narratives that make up the large-scale reasoning of the world (Boje 2019). The external-facing narratives of organizations, such as reports, webpages, social media postings etc. which were the unit of analysis in this study, are often a highly regulated type of narrative, the facade of a messier web of stories, interactions and artifacts through which an organization makes sense of and articulates its vision. Thus it is important to account for the specific intentions of how an organization may choose to display or hide specific ideas from this facade, or explicitly counter the dominant narratives. Which is why the methodology presented here would be most effective when combined with other methods of contextual research, that can capture many meanings that might get concealed within the chosen and imposed limits of how an organization tells its story.

Lastly, we would like to remind readers that narratives are not limited to textual material, but encompass a wide array of digital and physical artifacts through which we construct meaning. Although its use was limited within this project, in previous iterations, we found visual ethnography, both digitally and on-site, to be a helpful complement to the analysis of textual material. Small-scale organizations and local communities, who may have limited online presence. express themselves through more informal forms of communication such zines, murals, physical posters, placemaking, or oral storytelling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by NSF Grant # 2115405 SRS RN: Multiscale RECIPES (Resilient, Equitable, and Circular Innovations with Partnership and Education Synergies) for Sustainable Food Systems. Findings and conclusions reported here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

We wish to thank Jennifer Herd of the City of Chicago Department of Public Health and Stephanie Katsaros of Bright Beat Consulting for their partnership through the City of Chicago Food Matters project. We also extend our gratitude to the students of Design for Climate Leadership course at the Institute of Design, for their generous contribution of sharing their coursework, which made this study possible.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Azra Sungu is a PhD Candidate at the Institute of Design (ID) at Illinois Tech, and a Fulbright scholar. She is also a Graduate Assistant at the ID Food Systems Action Lab. Her research focuses on collective learning and visioning for societal and environmental transitions, with a particular interest in the role of narratives and design in shaping these processes. asungu@id.iit.edu

Weslynne Ashton is a Professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology with a joint appointment at the Stuart School of Business and the Institute of Design (ID). She also co-directs ID’s Food Systems Action Lab. As a sustainable systems scientist, her research, teaching, and practice are oriented around transitioning socio-ecological systems towards sustainability and equity. washton@iit.edu

Maura Shea is an Associate Professor of Practice at the Institute of Design (ID) at Illinois Tech focused on evolving community-led development methods and approaches. She is also the Co-Director of the ID Food Systems Action Lab, and worked as an innovation leader in national nonprofit networks for over a decade. mshea@id.iit.edu

Laura Forlano, a Fulbright award-winning scholar, is a disabled writer, social scientist and design researcher. She is Professor in the departments of Art + Design and Communication Studies in the College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University. She received her Ph.D. in communications from Columbia University. l.forlano@northeastern.edu

REFERENCES CITED

Baerten, Nik. 2019. “Napkin futures: Fragments of future worlds.” Journal of Futures Studies 23, no. 4: 117-122.

Bareis, Jascha, and Christian Katzenbach. “Talking AI into being: The narratives and imaginaries of national AI strategies and their performative politics.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 47, no. 5 (2022): 855-881.

Baumann, Karl, Ben Caldwell, François Bar, and Benjamin Stokes. 2018. “Participatory design fiction: community storytelling for speculative urban technologies.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-1.

Bien, C., and Sassen, R. 2020. “Sensemaking of a Sustainability Transition by Higher Education Institution Leaders.” Journal of Cleaner Production 256: 120299.

Boje, David M. “‘Storytelling Organization’ Is Being Transformed into Discourse of ‘Digital Organization.’” M@n@gement 22, no. 2 (2019): 336. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.222.0336.

Burdick, Anne. 2019. “Designing Futures from the Inside.” Journal of Futures Studies 23, no. 3: 75–92. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0006.

Candy, Stuart, and Jake Dunagan. “Designing an experiential scenario: The people who vanished.” Futures 86 (2017): 136-153.

Chateau, Zoé, Patrick Devine-Wright, and Jane Wills. 2021. “Integrating sociotechnical and spatial imaginaries in researching energy futures.” Energy Research & Social Science 80: 102207.

Chicago Beyond. 2019. Why Am I Always Being Researched?. https://chicagobeyond.org/researchequity/. Accessed September 10, 2023.

Chicagoland Food & Beverage Network (n.d.) https://www.chicagolandfood.org/. Accessed February 13, 2023.

Dawson, Patrick, and David Buchanan. 2005. “The way it really happened: Competing narratives in the political process of technological change.” Human Relations 58, no. 7: 845-865.

Dobroć, Paulina, Paula Bögel, and Paul Upham. 2023. “Narratives of change: Strategies for inclusivity in shaping socio-technical future visions.” Futures 145: 103076.

Fairclough, Norman and Wodak, Ruth. 1997. “Critical Discourse Analysis” In Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, edited by Teun A. van Dijk. 2: 258-284. London: Sage.

Forlano, Laura. 2019. “Cars and contemporary communications| Stabilizing/destabilizing the driverless city: Speculative futures and autonomous vehicles.” International Journal of Communication 13: 28.

Friedrich, Jonathan, Katharina Najork, Markus Keck, and Jana Zscheischler. 2022. “Bioeconomic fiction between narrative dynamics and a fixed imaginary: Evidence from India and Germany.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 30: 584-595.

Gee, James P. 2014. An introduction to discourse analysis theory and Method. London: Routledge.

Gee, James P. 2017. “Discourse Analysis.” Chapter. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Dialogue, edited by Edda Weigand, 62–77. Routledge.

Goodson, Ivor F., and Scherto R. Gill. 2011. “The Narrative Turn in Social Research.” Counterpoints 386 (2011): 17–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42981362.

Green Era. (n.d.) “Urban Farm”. https://www.greenerachicago.org/campus/urban-farm. Accessed March 12, 2023.

Groves, Christopher. 2017. “Emptying the future: On the environmental politics of anticipation.” Futures 92 : 29-38.

Halse, Joachim. 2020. “Ethnographies of the Possible.” In Design anthropology, pp. 180-196. Routledge.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective.” Feminist studies 14, no. 3: 575-599.

Harrington, Christina N., Shamika Klassen, and Yolanda A. Rankin. 2022. “‘All That You Touch, You Change’: Expanding the Canon of Speculative Design towards Black Futuring.” CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3502118.

Howell, Noura, Britta F. Schulte, Amy Twigger Holroyd, Rocío Fatás Arana, Sumita Sharma, and Grace Eden. 2021. “Calling for a plurality of perspectives on design futuring: an un-manifesto.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-10.

Inayatullah, Sohail. 1990. “Deconstructing and reconstructing the future: Predictive, cultural and critical epistemologies.” Futures 22, no. 2: 115-141.

Inayatullah, Sohail. 1998. “Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method.” Futures 30, no. 8: 815-829.

Jaede, Maximilian. 2017. “The Concept of the Common Good.” PSRP Working Paper 8.

Jasanoff, Sheila, and Sang-Hyun Kim. 2013. “Sociotechnical imaginaries and national energy policies.” Science as culture 22, no. 2: 189-196.

Jasanoff, Sheila, and Sang-Hyun Kim. 2015. Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. University of Chicago Press.

Kania, John, and Mark Kramer. 2013. “Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. Accessed October 7, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48558/ZJY9-4D87.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2006. The semantic turn: A New Foundation for Design. Boca Raton: CRC/Taylor & Francis.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2020. Communication, Conversation, Discourse and Design. In Matters of Communication – Formen und Materialitäten gestalteter Kommunikation, edited by Foraita, S., Herlo, B., & Vogelsang, A. (Ed.), Matters of Communication – Formen und Materialitäten gestalteter Kommunikation (pp. 21-36). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839451182-003.

Latour, Bruno, and Peter Weibel. 2005. Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mansbridge, Jane and Boot, Eric. 2022. “Common Good.” In International Encyclopedia of Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444367072.wbiee608.pub2

Mazé, Ramia. 2019. “Politics of designing visions of the future.” Journal of Futures Studies 23, no. 3: 23-38.

Moezzi, M., Janda, K. B., and Rotmann, S. 2017. “Using Stories, Narratives, and Storytelling in Energy and Climate Change Research.” Energy Research & Social Science 31: 1-10.

Mouffe, Chantal. 2000. The Democratic Paradox. Verso.

ORS Impact. 2021. Measuring the narrative change. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.orsimpact.com/DirectoryAttachments/3102021_103034_594_ORS_Impact_Measuring_Narrative_Change_2.0.pdf.

Nogueira, André, Weslynne S. Ashton, and Carlos Teixeira. 2019. “Expanding perceptions of the circular economy through design: Eight capitals as innovation lenses.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 149: 566-576.

NRDC. (n.d.). Food Matters – NRDC. https://www.nrdc.org/food-matters. Accessed September 20, 2023.

Paxling, Linda. 2019. Transforming Technocultures: Feminist technoscience, Critical Design Practices and Caring Imaginaries. PhD diss., Blekinge Tekniska Högskola.

RefED. n.d. “Solutions Database”. RefED Insights Engine website. https://insights-engine.refed.org/solution-database?dataView=total&indicator=us-dollars-profit. Accessed September 3, 2023.

Riedy, Chris. 2020. “Storying the Future: Storytelling Practice in Transformative Systems.” Essay. In Storytelling for Sustainability in Higher Education an Educator’s Handbook, edited by Petra Molthan-Hill, Denise Baden, Tony Wall, Helen Puntha, and Heather Luna. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Southern, Jen, Rebecca Ellis, Maria Angela Ferrario, Ruth McNally, Rod Dillon, Will Simm, and Jon Whittle. 2014. “Imaginative labour and relationships of care: Co-designing prototypes with vulnerable communities.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 84: 131-142.

Speed, Chris, Bettina Nissen, Larissa Pschetz, Dave Murray-Rust, Hadi Mehrpouya, and Shaune Oosthuizen. 2018. “Designing new socio-economic imaginaries.” The Design Journal 22, no. sup1: 2257-2261.

Suchman, Lucy. 2008. “Feminist STS and the Sciences of the Artificial.” The handbook of science and technology studies 3: 139-164.

Tharp, Bruce M., and Stephanie M. Tharp. 2019. Discursive design: critical, speculative, and alternative things. MIT press.

Tidwell, Jacqueline Hettel, and Abraham SD Tidwell. 2018. “Energy ideals, visions, narratives, and rhetoric: Examining sociotechnical imaginaries theory and methodology in energy research.” Energy Research & Social Science 39: 103-107.

Tran O’Leary, Jasper, Sara Zewde, Jennifer Mankoff, and Daniela K. Rosner. “Who Gets to Future?” Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300791.

Wittmayer, Julia, Julia Backhaus, Flor Avelino, Bonno Pel, Tim Strassser, and Iris Kunze. Working paper. Narratives of Change: How Social Innovation Initiatives Engage with Their Transformative Ambitions, October 2015. http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/content/original/Book%20covers/Local%20PDFs/181%20TRANSIT_WorkingPaper4_Narratives%20of%20Change_Wittmayer%20et%20al_October2015_2.pdf.

Wittmayer, Julia M., Julia Backhaus, Flor Avelino, Bonno Pel, Tim Strasser, Iris Kunze, and Linda Zuijderwijk. 2019. “Narratives of change: How social innovation initiatives construct societal transformation.” Futures 112: 102433.

Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer. 2018. Methods of critical discourse studies. 3rd ed. Sage.