This case study demonstrates how a transdisciplinary, human-centered approach to research and process improvement can increase efficiency, enrollment, and customer experience across a complex ecosystem of organizations, people, processes, and technologies. In the wake of an executive order to improve customer experience and service delivery, a team at the United States Digital Service (USDS) worked with Centers for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program Services and state program teams to improve Medicaid eligibility and enrollment. USDS used a mixed-methods research approach that centered lived experience, and mobilized small strike teams to systematically review software and processes. The ROI was substantial: USDS estimates that this work facilitated over 5 million automatic renewals and saved state employees and the public approximately 2 million hours of burden by the end of 2024.

Introduction

This case study explores the work of the United States Digital Service (USDS) in partnership with Centers for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) and state Medicaid offices to streamline and improve the Medicaid redeterminations process for enrollees, application assistors, and state staff. This work is part of an interagency program supporting President Biden’s Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government. The Presidential Management Council formed a cross-government effort and interagency team to tackle the designated life experience of facing a financial shock and becoming newly eligible for critical supports.

In response to the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) in 2020, Congress enacted several policies to protect Americans. Among these was a continuous enrollment provision that allowed states to maintain Medicaid and CHIP coverage for enrollees throughout the duration of the PHE—a policy that protected health care coverage for, at its peak, more than 90 million eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults and people with disabilities (Medicaid, 2023). This provision expired on March 31, 2023, and states were given 12–14 months to resume annual redeterminations: the process of verifying enrollees’ eligibility to either renew or terminate their coverage. The period following the end of the continuous coverage provision in 2023 and return to normal operations is often referred to as the “unwinding” period.

Medicaid agencies around the country faced a massive challenge: to conduct redeterminations for a record number of enrollees with fewer staff, rebooting systems that sat dormant during the pandemic, and finding up-to-date enrollee contact information for the first time in three years. Many enrollees had never experienced the redetermination process before, having received Medicaid for the first time during the pandemic, and thus did not know what was required of them.

Estimates from 2022 projected that over 7 million people were at risk of losing their health care coverage—not because they were no longer eligible—but because of technological and administrative barriers including undelivered mail, burdensome renewal packets, and/or system errors (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2022).

This case study describes how some of the challenges faced by states during this time were met with a transdisciplinary human-centered design (HCD) approach. USDS, a component of the Office of Management and Budget, specializes in technology and design. USDS, in partnership with CMCS, joined the all-of-government response to unwinding to bridge the gap between policy and the challenges of implementation through a series of intensive sprints with 8 states from March 2023 to April 2024. Applying a mixed-methods research approach and leveraging the power of a cross-functional technology team, USDS’s efforts resulted in the reduction of millions of hours of burden time and improved customer experience of Medicaid renewals for enrollees, application assistors, and eligibility workers.

Project Context

The Impact of COVID on Medicaid

Program History and Foundational Policies

Medicaid is a public program that provides low-income Americans, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people with disabilities with health care coverage. Administered by states and funded jointly with the federal government, Medicaid was established in 1965 within Title XIX of the Social Security Act. It was created to provide a healthcare coverage option for those who could not access private health insurance or other medical support (Medicaid.gov, n.d.).

The continuous enrollment provision that was enacted as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) allowed eligible Medicaid enrollees to receive health coverage for the duration of the pandemic—for some, that meant 3 years of continuous coverage. Under most circumstances, Medicaid enrollees are only entitled to coverage for 12 months, after which, states must conduct a redetermination of eligibility to either renew or terminate the enrollee’s coverage.

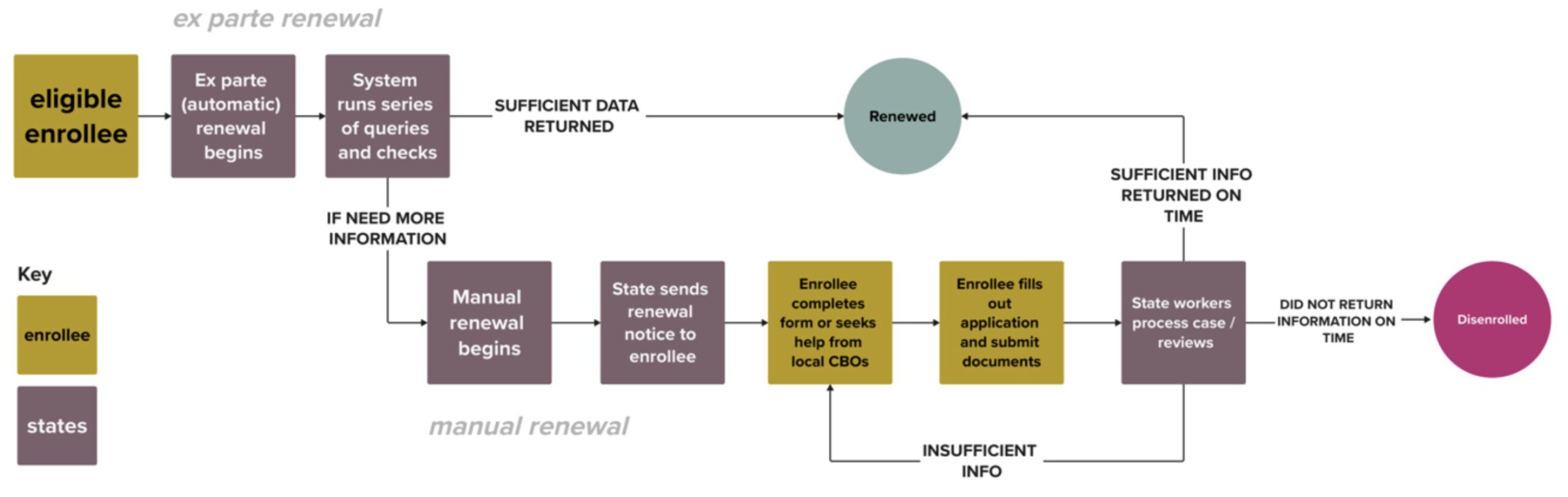

There are two possible renewal pathways an enrollee may experience: (a) “automatic” renewal wherein a state uses electronic data sources to verify eligibility, or (b) “manual” renewal wherein the enrollee provides eligibility information by completing a form and including any necessary documentation (such as proof of income). The two experiences vary dramatically for both the enrollee and state eligibility workers who process annual renewals.

Figure 1: Simplified Medicaid Renewal Journey for an eligible individual. State implementations of Medicaid Renewal pathways vary. This is for illustrative purposes only.

In the first renewal pathway, if a state can verify eligibility using existing data, no action is required of the enrollee. Referred to as “ex parte,” this automatic renewal process saves time for both eligibility workers and enrollees. According to 42 CFR 435.916(b), state must attempt ex parte renewal before requesting additional information from the enrollee.

If states are unable to verify eligibility on an ex parte basis, enrollees are required to manually complete and return a renewal form verifying that no information has changed from the time of application or updating information if it has. The manual renewal form can commonly be completed online, on-paper, or over-the-phone, and states must pre-populate the form with existing information (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, n.d.). Across most states, the end-to-end renewal form can be over a dozen pages long.

Framing the Problem: Policy, Meet Implementation

Both regulations mentioned above are intended to reduce administrative burden on enrollees, and to save eligibility workers time in processing renewals. With these time-saving policies on the books, one might wonder why reinstating annual renewals posed such a challenge for states, and why millions of Americans were at risk of losing their health care coverage during the unwinding period.

The first challenge states faced was the sheer volume of renewals that needed to be completed during the unwinding period. During COVID, because of the continuous enrollment condition, enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP skyrocketed, with roughly 94M people enrolled in the program by the end of the pandemic; this was a gain of close to 23M eligible people in the program in just 3 years (Medicaid.gov, n.d.). At the same time, state Medicaid agencies were facing staff shortages, many hurrying to hire and train new eligibility workers to complete redeterminations for the first time. CMCS described this period as, “the single largest health coverage transition event since the first open enrollment period of the Affordable Care Act.” (Medicaid.gov, n.d.)

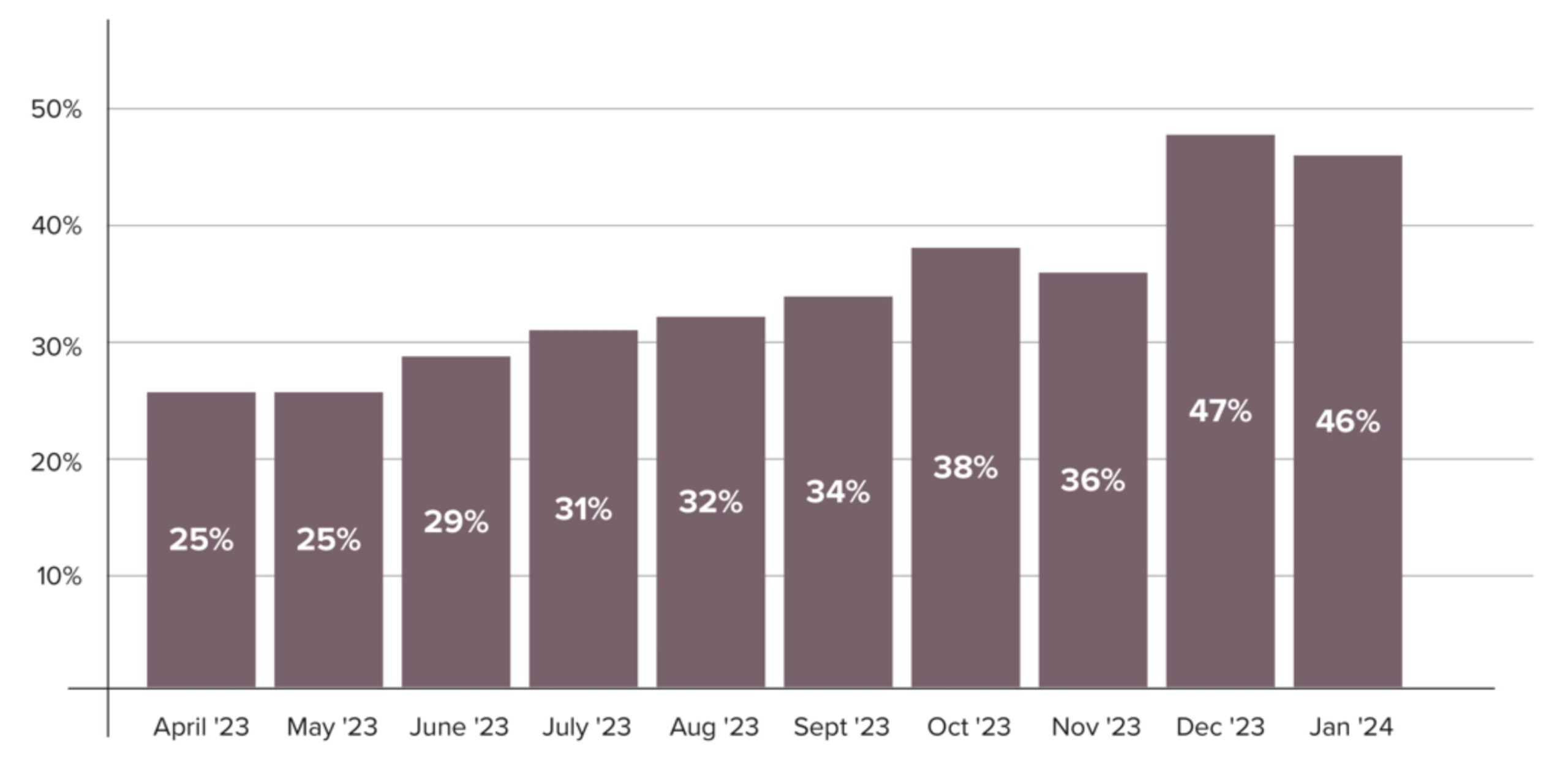

Given this historic volume of enrollees, states looked to better leverage automatic renewals in order to improve compliance, process redeterminations on time, and reduce the load on strained eligibility worker. However, many states struggled with low ex parterates—at the start of redeterminations, states processed only 1 in 4 of their redeterminations on an ex parte basis (Medicaid.gov, n.d.).

Figure 2. Average national ex parte rate broken down by month. Data from https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/data-reporting/monthly-data-reports/index.html.

While this may seem like a simple problem to solve, the reality is that federal policy makers must navigate a complex landscape of Medicaid and CHIP programs across 56 states and territories that each have their own operating constraints. Each Medicaid program has a bespoke eligibility system, different data integrations, distinct eligibility criteria, and different demographic compositions. Some states, but not all, have expanded eligibility under the Affordable Care Act; additionally, some Medicaid programs are integrated with other health and human services programs like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). This diverse ecosystem not only makes a “simple” task of setting performance benchmarks a challenge, but also complicates the process of creating implementation guidance, such as use-cases, that capture all of the variance in these programs.

For the remaining cases that could not be processed automatically, states were preparing to mail out and process historic numbers of manual renewals. Medicaid offices faced an entirely different set of challenges, such as undeliverable or delayed mail to recipients; the public’s general lack of awareness and understanding of what the unwinding period was; and challenges in the experience of completing renewal forms due to poor UX on websites and the lack of plain language in the guidance of how to complete them.

Hypothesis

From early conversations with state Medicaid agencies, CMCS leadership, and USDS’s desk research, the team hypothesized that a) helping state agencies optimize automatic renewals, and b) decreasing barriers throughout the manual renewal process would provide time and cost savings for the state while providing a streamlined and more equitable experience for the enrollee. The team proposed going on the ground with states with a small cross-functional team, could make a considerable impact to states during this historic transition.

Framing the Project Approach

CMCS and state Medicaid offices are not alone in this struggle between writing the policy and implementing it to produce its intended outcome. In 2008, the National Academy of Public Administration surveyed career policymakers in federal government and found only “16% consider government proficient at designing policies that can actually be implemented” (Pahlka, 2020).

Examining Structural Foundations of Government Service Delivery

Jennifer Pahlka, in her book Recoding America, explores “the temporal, organizational, structural, and cultural gaps between policy and tech teams, and between tech teams and the users of that tech,” through dozens of examples across federal and state government (Pahlka, 2023:16). By examining these gaps and challenging the behaviors and beliefs that created them, Pahlka urges technologists and policymakers alike to join together. The structures that created these gaps, however, are strong. Pahlka notes:

Chief among [government’s dysfunctions] is a structure and way of thinking deeply rooted in American culture: hierarchy. …What’s valued in government isn’t the nuts and bolts of implementation but the rarefied work of policymaking. Digital work…in government is reduced to an afterthought. It’s not what important people do, and important people don’t do it. … At times it almost seems that status in government is dependent on how distant one can be from the implementation of policy (Pahlka, 2023:15).

The USDS team knew that to be successful it would require a cross-functional team that met states where they are. This approach allowed the team to bring implementation expertise in design, engineering, data science, and product directly to states, with the added benefit of having direct connections with the agency that knew each policy’s intention. The team’s experience working at, with, or adjacent to vendors also meant that the team could understand the language and culture of state vendor teams and support the translation between policy ideals and goals to the nuts and bolts of implementation.

These approaches are unusual in government. While the civic technology field is growing, many states and government agencies do not have access to this type of expertise. By engaging with states directly and helping define the problem and work together to operationalize ways to solve it, the team aimed to encourage a reimagining and reworking of how technology could be implemented at the state level.

An Introduction to USDS Values and Process

USDS holds six values that drive the approach to delivering better government services. These include (1) Find the truth, tell the truth, (2) design with users, not for them, (3) go where the work is, (4) optimize for results, not optics, (5) create momentum, and (6) hire and empower great people (usds.gov, n.d.). While all tenets influenced the team’s approach to the work, the first three helped underscore how the team made decisions around methodologies and implementation. Namely, this informed the decision for the team to go on the ground to meet with states directly, to engage community-based organizations and staff working on the front lines early and often, and to bring up hard discussions for the betterment of the service for the public beneficiaries and state staff overall.

Similarly, USDS strives to engage multi-disciplinary teams to ensure that projects have cross-functional specialties that can meet any challenge. For this project, the USDS team consisted of 4 human centered designers, 4 engineers, and 2 product managers. The cross-cutting nature of benefit services meant that data science and engineering were a vital skill needed to understand the technical systems used in implementing the policies and eligibility determinations, while designers led research of surrounding support services, public facing workshops, and redesigns of visual touchpoints and operational practices. The cohesion of the team meant that each practitioner brought their own lens to challenge, champion, and support the various workstreams to strengthen the final results.

Focusing on Addressing Administrative Burden

As noted by Herd and Moynihan in their book Administrative Burden, changing foundational ways of working can be deeply challenging for many reasons. While policy makers work to develop programs, structures, and rules to support American livelihoods, unintended consequences can come about during implementation, such as costs, access difficulties, and user experience challenges (Herd and Moynihan, 2018). This friction in completing tasks that allow someone to receive results is known administrative burden. The stress, frustration, and lack of ability to complete tasks for these programs can end up impeding access for the very people the programs are trying to serve. Don Moynihan sums this up well in the following example:

We go through life with a set of expectations about how our interactions with administrative services work. And over time, if we are dependent upon certain services, if there’s a change in those, it can have these fairly dramatic effects. And so there are other examples in, for example, Arkansas when they introduce work requirements for Medicaid. A paper in the New England Journal of Medicine founded about 95% of those who lost their Medicaid coverage due to the work requirements were actually working or should have been exempted because of a disability, but where they really struggled was with the paperwork requirements. It was really the reporting part that they found difficult. It wasn’t that they weren’t actually completing the eligibility guidelines. (Grossman et. al., 2023).

For Medicaid, the repercussions of administrative burden can be the difference between having lifesaving health coverage or not. As Wilke et. al. point out, much has been done to reduce burdens within the Medicaid program, like removing the need for in person interviews, but other burdens still exist, such as requiring signatures on applications (Wilke et. al., 2022).

For CMCS and the USDS team, reducing administrative burden meant focusing on ways the team could decrease the touchpoints the public had in their renewal experience. And when they could not, the focus would be improving the experience of these touchpoints when it was essential to have that interaction.

Transitioning from Executive Order to Implementation

The Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government declares that government should return to focusing on a government of, by, and for the people, and that government programs and services should be held accountable for designing and delivering services with a focus on the actual experience of the people whom it is meant to serve. It particularly calls out the use of HCD methodologies the federal government’s management of its customer experience and service delivery should be driven fundamentally by the voice of the customer through human-centered design methodologies.

While the Executive Order was issued in 2021, these methods are still fairly new in government settings. When starting this project, USDS was aware that CMCS and states had probably heard some design terminology, but had most likely not worked in the applied design and technology practice that the team are experts in. This meant that many approaches that were familiar to USDS, such as interviewing beneficiaries or their supporters, prototyping, and more could seem unfamiliar and polarizing to start. That, in tandem with our focus on moving quickly, meant that USDS had to ensure stakeholders were aware and engaged in each step of the process.

Doing so meant encouraging states to rethink the foundations of how program implementation had been carried out in many federal benefit programs and directly challenging “the durability of social conventions and cultural traditions and thus resistance to organizational transformation” (The White House, 2021). In the past, this has looked like implementing programs without feedback from the public or siloing policy and technology teams away from each other. USDS knew that building trust with the state teams would be vital to be successful. As such, the USDS team engaged key principles of empathy, stakeholder engagement and participation, and visualization to ensure states and CMCS were on board and consistently aware of the processes.

Research Design and Methodology

State Selection Criteria

USDS assessed the need, capacity, and potential for impact across all 56 states and territories using key criteria such as Medicaid population size and composition, state processing times, and recent ex parte rates. After reviewing the states against these criteria and working with CMCS, the team identified potential partner states. All states then had an opportunity to express their interest in receiving technical assistance. Based on state interest and the team’s need analysis, they conducted interviews with a subset of states to identify and prioritize their state partners.

From these interviews USDS and CMCS selected 8 states to provide in-depth technical assistance. States were chosen based on the following factors: need, potential for impact, and capacity to accept help. Once chosen, USDS provided hands-on technical assistance, which is further detailed below.

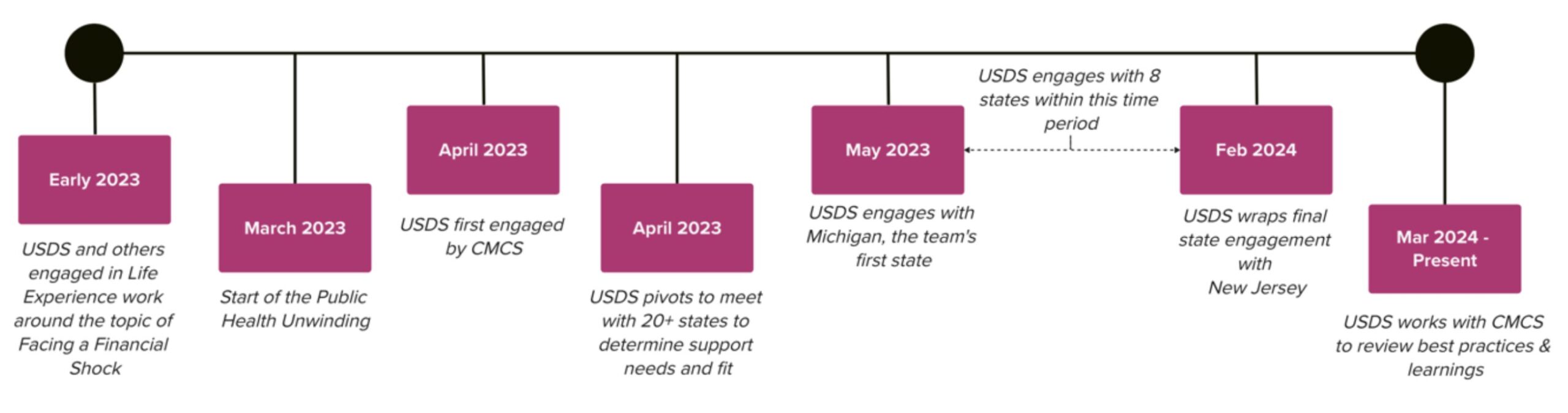

Figure 3: Timeline of USDS engagement with CMCS and states.

Rapid Response Framework

Implementation through Hands-on Technical Assistance

Central to the team’s approach was to meet states where they were. This included not just going on site to visit states, but also working with states’ policy, operations, and technical teams to understand their constraints and identify areas of impact. This work generally moved through three phases:

- Preparatory Research. Activities included: conducting virtual kick offs with state leadership; collecting data from the state to aid in prioritization of impact areas; and conducting one-on-one semi-structured interviews with state subject matter experts and community-based organizations.

- One Week Onsite Sprint. The team went on the ground in each state for one week and conducted an onsite visit, which included 4-5 days of intensive meetings centered around challenges, then collaboratively with stakeholders working towards identifying potential approaches and creating implementation plans for a few key ones prioritized by the state.

- Follow-on Implementation Support. USDS provided implementation support, general project management, and technical advice for the 2-4 weeks following the onsite.

This multi-stage approach allowed the team to align with the states’ needs in advance of onsite engagement, therefore creating the opportunity for more intense and focused work while in the state. It also allowed state actors to ease into the asks USDS and CMCS were making, and building trust and relationships through the process.

Creating Evidence-Driven Prioritization through Data Visualization

CMCS requires states to submit data about their Medicaid enrollments, renewals, and compliance to federal regulations. During the unwinding period, CMCS required states to report on the number of renewals that were processed on an ex parte basis each month. This meant that many states had data already in hand that USDS was able to use to create an evidence-driven approach to prioritization.

While the ex parte data was useful, it was only one piece of the puzzle. To tell the full picture of where enrollees and states were facing administrative burden throughout the renewals process, the USDS team needed to gather data and understand processes from eligibility workers, technology vendors, and operations teams. USDS brought all of these actors together to collaboratively identify the greatest opportunities to streamline the renewals experience.

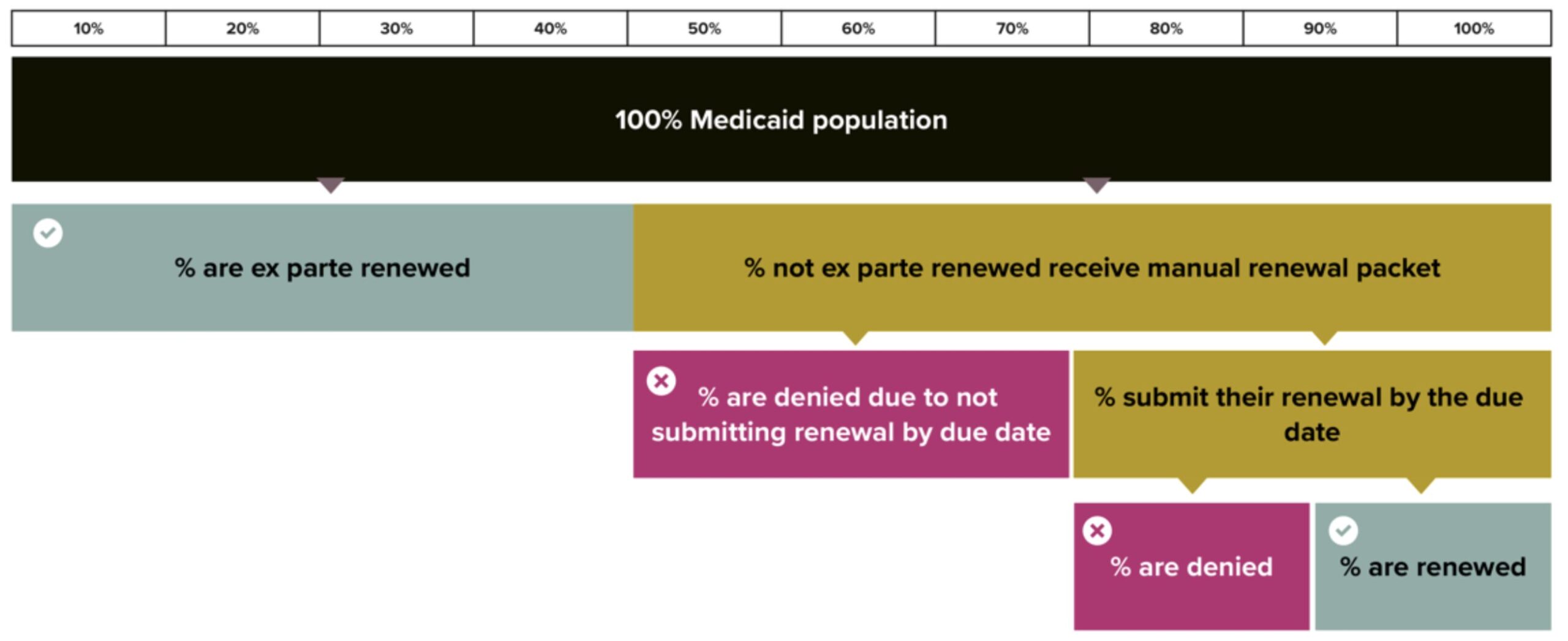

To help facilitate and communicate the data requests and analysis, the USDS team used data visualization to support the team and state’s understanding of where beneficiaries were exiting the renewal process. Referred to as “the funnel” by the team, the visualization leveraged state data at key points in the customer journey to highlight where these drop off points were occurring. In particular, the funnel allowed the team to identify the gaps between the ex parte process and the multiple steps that happen during the manual renewal, and solidify the extent to which manual renewals should be a priority. The reframing of the data into an end-to-end view of the beneficiary experience allowed for USDS team to leverage their expertise in two workstreams: one focused on implementation of policy into state technological systems, and the other around improvements to the various steps involved in the manual renewal process.

Figure 4. Example of USDS funnel data visualization. Starting from 100% of Medicaid population, the funnel continues down showcasing who is ex parte renewed and the steps involved in the manual renewal process.

Using this data-driven approach was novel for many states, who often approached their data piecemeal rather than holistically. Upon seeing the breakdown of their data in this new way, state leadership and implementors were able to clearly grasp the extent to which each step in the beneficiary process was either working or needed attention. While the data was essential to understand each state’s ex parte challenges, this data driven approach was particularly beneficial in allowing USDS and states to collaboratively align on where to prioritize for interventions within the manual renewal process.

Service Design Methodology

Secondary Research and Heuristic Analyses

The USDS team spent between 2-4 weeks reviewing existing materials related to each state’s context before going onsite. This included reviewing news articles, combing through social media, reading state-specific policy documents, analyzing search engine results, in combination with other materials to understand the state’s current context.

In parallel to reviewing documentation, USDS would conduct a heuristic analysis of the state’s beneficiary-facing materials, including paper forms, websites with applications, and mobile apps. The team would note any potential challenging areas they encountered, such as plain language concerns and with user experience issues.

Finally, using a mystery shopping approach, USDS called into the state’s call center to evaluate how renewals were presented to callers. The team reviewed the system’s interactive voice response phone trees for plain language, timing, and ease of use. When the team was able to reach a customer representative, USDS tried to get clear answers around how to apply during the renewal period.

This broad and quick review provided general insight into each states’ specific Medicaid ecosystem and allowed the team to get a high-level understanding of challenges beneficiaries were experiencing.

Qualitative Research

The USDS team engaged a range of qualitative methods to help inform their strategic approach to implementation. One of the main approaches was the use of semi-structured interviews, particularly with community-based organizations (CBOs). Working collaboratively with state leadership, USDS held conversations with key CBO groups in lieu of talking directly with beneficiaries. USDS chose to do this because of the rapid timeline of implementation and the expert knowledge CBOs have gathered from their front-line work; their breadth and depth of experience was gauged to be a much deeper synthesis than what USDS could understand with only a few interviews done during a week of research.

The team also leveraged CBOs in applied focus groups or listening sessions. These sessions often created opportunities to share USDS created customer journey maps and to work with CBOs to pin point critical pain points. In these sessions, USDS engaged front-line staff, including application assisters and case workers, to confirm the challenges they were seeing beneficiaries have, and sometimes engaged them to speak to solutions that might mitigate administrative burden within the Medicaid program.

Synthesis and Service Design Mapping

USDS created customer journey maps, service blueprints, and data visualizations to support the synthesis, analysis, and communication of information gained within the team, to CMCS, and with the states. These materials often created the basis for conversations and group convenings.

While common with design and technology practitioners in the private sector, government does not always have the capacity to attempt these types of synthesis methods. USDS found that visualizing the outputs of synthesis encouraged those unfamiliar with our methodologies to understand the information faster, engage more directly, and ask more detailed questions than when presenting only in an auditory or text format.

Facilitation and Group Convenings

Central to the team’s approach was convening all stakeholders into one room for the duration of the onsite. This included state leadership, eligibility workers, and various implementation staff to review the research done to date and then work together to prioritize and initiate new approaches together. The USDS team leveraged collaborative problem-solving methods and facilitated design workshops to document end-to-end processes in real time as the group discussed potential implications from both technical and procedural standpoints. These conversations began to lay new foundations of how to collaborate across various departments and disciplines, and bring policy and implementation pillars closer together. They also captured decision making in real time and provided concrete references to refer back to over the week.

USDS also led collaborative design workshops to ideate on solutions that emerged from the qualitative research with CBOs. Potential solutions that emerged included streamlining the renewal form design, new forms of communication with beneficiaries, and streamlining the call center experience. This meant constantly bringing those in the room back to the challenges beneficiaries were facing.

Implementation Support: Project Management, Applied Design, and More

USDS supported each state for up to 4 weeks in implementing the outputs from the onsite. Often, this meant supporting conversations between the state and their vendor, translating between policy and technological implementation. As the partner states were managing their normal workload on top of this engagement, USDS often assisted in keeping track of tasks, updating state leadership, and maintaining forward momentum.

Due to the multidisciplinary nature of the USDS team, implementation support also meant occasionally designing the drafts or final version of outputs. This included things like writing copy for new text messages or mocking up new designs for websites.

Impact of Direct Technical Assistance

The USDS team in partnership with CMCS and states were able to improve not only ex-parte results but the customer experience of Medicaid redeterminations in the states they visited.

Common Manual Renewal Challenges

A benefit of working across multiple states and in collaboration with CMCS was being able to see broadly across the federal ecosystem. By visiting 8 states for this work, USDS was able to identify common renewal challenges from a CX perspective.

The challenges the team found included: difficulty in communications and outreach to beneficiaries, particularly around the use of plain language; low access to and low usability of renewal forms; challenging call center access and navigability; lack of modern mobile development and user experience practices; a dearth of feedback loops from beneficiaries to state policy and technology teams; and a shortage of talent at the state level who brought capacity to oversee vendors.

While each state had many of these challenges broadly, the difference between the implementation needs of these were bespoke due to each state having individual eligibility systems, processes, and standard operating procedures. Outputs are therefore not easy to categorize.

Automatic Renewal Impact Numbers

Because the work for both manual renewals and ex parte go hand in hand in providing a full experience to beneficiaries, we consider our impact numbers collaborative and shared. When combining the work of both approaches in this project, the entire engagement across all states supported an estimated 5 million additional Americans to be renewed for health coverage via ex parte processing in 2024. The project was also estimated to have saved 2 million hours of eligibility worker processing time in 2024 (Medicaid.gov).

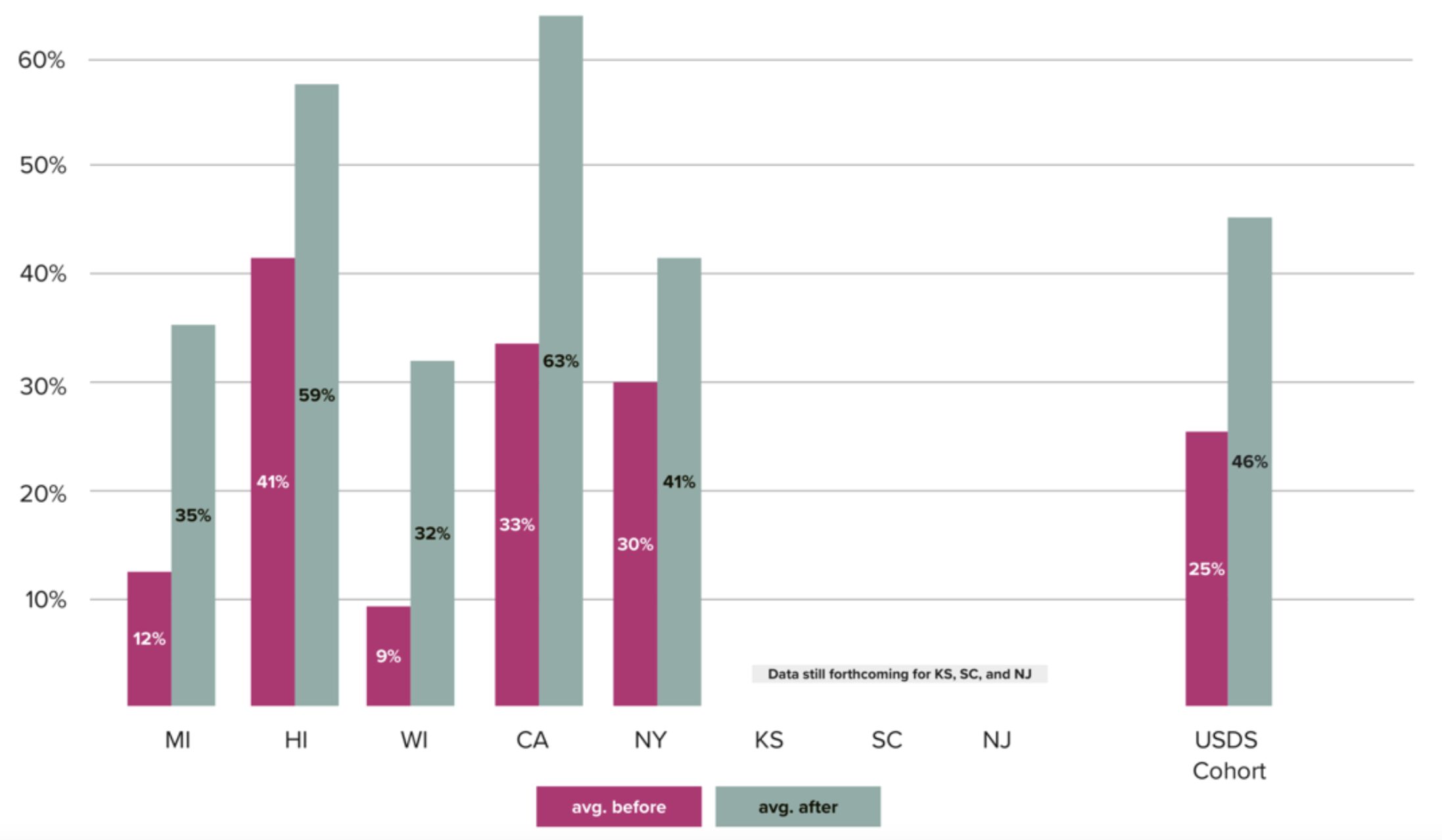

For example, within New York, the work on both ex parte and manual renewals helped increase their ex parte rates to 44% based on data reported to Medicaid that compares the data pre-USDS visit and post-visit by April 2024 (Medicaid, n.d.). In California, rates increased to 63%, representing a 30% increase. For the entire engagement, the average change in ex parte rate was 21%, and the average reduction in procedural termination rate for states that engaged with us was a decrease of 10%. See Figure 5 for more details.

Figure 5. Average percentage of monthly renewals completed ex parte before and after USDS intervention. Average is the average for between May 2023 and April 2024, for which data is available. Data currently is not available for KS, SC, and NJ. HI data is only from June through Sept. from pausing redeterminations due to wildfires. Please note that this analysis is limited, as it does not take into account individual changes made to state systems or monthly population various unrelated to USDS interventions. Data source: https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwin%5b…%5dfter-covid-19/data-reporting/monthly-data-reports/index.html.

Discussion

Changing Federal Foundations and Shifting Mental Paradigms

While this work had direct impact on Medicaid recipients and state systems issuing eligibility determinations, much of what the team learned is applicable across federal policies that require state implementation, no matter the program. This points to common learnings that can be leveraged by anyone working in civic tech and guide the space to shifting the foundations and paradigms of how we currently operationalize policy.

Improving State Coordination with Community Organizations

Community based organizations often partner closely with states to help guide enrollees or prospective members to the right information. In many cases, these CBOs often help beneficiaries apply directly. States often have good working relationships with their CBO partners, but often struggle to find ways in which to balance CBO’s advocacy with implementation and policy.

Through this engagement, USDS leveraged its expertise in facilitation and design research to help bridge that divide. By hosting design workshops, USDS was able to uplift multiple CBO challenges to state partners in real time with tangible examples; it also encouraged CBOs to brainstorm solutions or approaches to these challenges, giving state leaders opportunities to identify which might be feasible and which were currently out of scope. States have mentioned that opening these lines of direct communication in a collaborative setting have changed the ways in which they think about receiving and prioritizing feedback. As implementation becomes more paramount to delivering on the policy goals, it may behoove federal programs to engage CBOs and other state partners in new ways.

Leveraging Technical Expertise to Shift Paradigms and Change Mental Models

State staff are deeply dedicated to their work. They however face a complex, dynamic, and opaque environment when operating Medicaid. While many are policy experts, wider state staff teams do not typically include technical experts to oversee or support their state vendor’s implementation of policy regulations. As a result, policy intent may not match technical implementation, or inefficient and antiquated processes may get built into systems without pressure to initiate changes that would better benefit a technological approach.

USDS was able to help demonstrate and provide new ways of working by showcasing the value of cross-functional implementation support. This technical expertise in logic and engineering systems, service and user experience design, and product management allowed for a bridge between policy intent and technical build; by connecting various subject matter experts with complementary expertise to inform decision making, and clearly articulating and synthesizing the challenges to outline options for senior level staff, teams were able to collectively agree upon goals and plans to initiate work in vendor roadmaps.

These changes have helped to shift state and federal teams’ mental models around the ways in which they communicate between stakeholders and how to better engage with vendors. By focusing on clear prioritization and technical implementation, states were able to improve experiences for staff and enrollees. States reported that these changes were lasting—after a USDS engagement, previous resistance to new changes were not as entrenched moving forward.

Institutionalizing Implementation for Long Term Impact

In partnership with CMCS and states, USDS worked to ensure that these approaches and ways of working could continue without their presence. The team also supported states in building their capacity, including giving guidance on how to start a Member Experience Advisory Council or hiring new talent with technical experience.

During this work, USDS was only able to engage with 8 states due to the nature of the rapid response approach. While learnings have been shared and championed by CMCS, there is a stark need for technical expertise across various fields to work with, for, and in support of federal programs and various levels of government. While the USDS team has advocated for hiring employees within programs in addition to working with excellent vendors, more talent is required. Civic technology organizations, vendors, and individual talent are all needed to help improve the experience the public has with federal and state systems.

Conclusion

By examining the foundations of the Medicaid renewal experience, the USDS team hopes that this case study demonstrates how federal programs can be redesigned by challenging long held assumptions, refocusing on systemic implementation, and centering the lived experience of Medicaid members, application assisters, and case workers, to transition towards a more service-driven benefit program.

By centering the lived experiences of case workers, application assisters, and Medicaid beneficiaries, government leaders can foster creating more efficient programs, decreased administrative burden, and better customer experiences for Medicaid beneficiaries and the front-line workers who support them.

Notes

Thank you to our state partners and CMCS colleagues for your dedication, trust, and willingness to partner with us. A special thank you to Max Mazzocchi, Chris Wren, Greg Novick, Navin Eluthesen, Luke Farrell, and Megan Cage for their support on the data in this study, as well as being great partners in the implementation of this project.

About the Authors

The authors are current or former employees of the United States Digital Service, part of the Federal Government. They prepared this article while acting in their official capacities as Federal Government employees. As a result, this article is a Federal Government Work and is in the public domain within the United States.

Alyssa Kropp is a service designer based in Brooklyn, NY. She has a love for participatory practices like co-design that she uses to help improve the design and delivery of government experiences. Currently she’s working with USDS to help strengthen federal programs, policies, and products across the benefits spectrum.

Emily Mann is an applied anthropologist who uses her ethnographic toolkit to improve the delivery of critical government benefits. At USDS, Emily has had the opportunity to work alongside civil servants to improve access healthcare benefits at multiple federal agencies including the VA, CMS, and SSA.

Heather Myers is a product designer who loves using design and research for the public good. She previously worked at USDS where she used her skills to address big challenges such as responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and reducing administrative burden for low-income Americans on Medicaid.

Izzie Zahorian is a Design Lead at USDS where she partners with agencies across government to improve the accessibility and usability of their services. She currently leads design research and service design on the Facing a Financial Shock charter established pursuant to President Biden’s Executive Order on customer experience (Executive Order 14058).

References Cited

42 U.S.C. §435.916(a)(2). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/part-435/subject-group-ECFR0717d3fdf4a090c#p-435.916(b)

42 U.S.C. §435.916(a)(3). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/part-435/subject-group-ECFR0717d3fdf4a090c#p-435.916(b)(2)

Corallo, Bradley and Moreno, Sophia. 2023. “Analysis of National Trends in Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/analysis-of-recent-national-trends-in-medicaid-and-chip-enrollment/

Grossmann, Matt, Donald Moynihan, Pamela Herd, and Niskanen Center. 2023. “How Administrative Burdens Undermine Public Programs. “Niskanen Center. https://www.niskanencenter.org/how-administrative-burdens-undermine-public-programs/

Heard, Pamela, and Moynihan, Donald P. 2018. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. Russell Sage Foundation.

Medicaid.gov. 2023. “January 2023 Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Snapshot.” Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/downloads/january-2023-medicaid-chip-enrollment-trend-snapshot.pdf

Medicaid.gov, n.d. “Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Trend Snapshot.” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-trend-snapshot/index.html

Medicaid.gov. n.d. “Monthly Data Reports.” Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/data-reporting/monthly-data-reports/index.html

Medicaid.gov. n.d. “Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Application, Eligibility Determination, and Enrollment Reports & Data.” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-medicaid-chip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-reports-data/index.html

Medicaid.gov. n.d. “Unwinding and Returning to Regular Operations after COVID-19.” Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/index.html

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. Issue Brief No. HP-2022-20. “Unwinding the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision: Projected Enrollment Effects and Policy Approaches.” https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/dc73e82abf7fc26b6a8e5cc52ae42d48/aspe-end-mcaid-continuous-coverage.pdf

Pahlka, Jennifer. 2023. Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better First edition., Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company.

Pahlka, Jennifer. 2020. “Digital Is Not Always Better Than Paper.” Medium. https://pahlkadot.medium.com/digital-is-not-always-better-than-paper-1f06dac2c900

The White House. 2021. “Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government.” www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/13/executive-order-on-transforming-federal-customer-experience-and-service-delivery-to-rebuild-trust-in-government/

Usds.gov. n.d. “Mission.” Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.usds.gov/mission