For several decades ‘Emerging’ has been a staple prefix applied to such entities as markets, nations, democracies, cultures, and business opportunities. The term has been used to label virtually anything about “less-developed” Others deemed “new” to the world of market-led consumption, especially by corporate actors looking for new markets and consumers worldwide.

Work in this area ranges from bottom-up players in the repair ecology of ICT businesses in a place like Dharavi, Mumbai, to top-down initiatives like Facebook’s internet.org, aiming to provide basic internet (framed as a human right) to disadvantaged citizens around the world. It explores topics as disparate as the dynamic worlds of micro-entrepreneurship and small and medium-sized enterprises; the desires of aspirational middle income groups in emerging contexts; or the strategies of actors near ‘the poverty line’, striving towards more socio-cultural prosperity in the same locations.

BoP (Base-of-the-Pyramid) was a powerful predecessor (and marketing mantra) that the late C. K. Prahalad made compelling by going beyond development ideology to characterise all ‘segments’ as active agents for at least some kind of consumption (and later conceptualized as potential business partners and innovators, not just consumers). But, following BOP’s demise as both discourse and research program, what lessons can we, as ethnographers, learn from the way it tried to account for this contested category of consumers, who are supposedly emerging—yet towards what? If BoP had had more of our input might it have fared better, or simply imploded later?

Last year ethnographers gathered in São Paulo, Brazil, for EPIC2015; the first time the conference was held in the “global south”. An impressive keynote address by Luciana Aguiar, Private Sector Partnerships Manager of the United Nations Development Programme in Brazil, outlined the tough challenges facing Brazil’s poor communities and the important contributions ethnographers can make in driving inclusive and sustainable business. Indeed, Brazil’s famous favelas are some of the oldest informal neighborhoods in the world, and innovative projects in these challenging urban spaces offer examples of how ethnography can help support practice in industry that prioritizes social inclusion. In this article, I explore urban mobility in favelas and invite you to submit proposals on your work to the EPIC2016 Paper Track “Ethnography/Emerging Consumers”.

Favelas

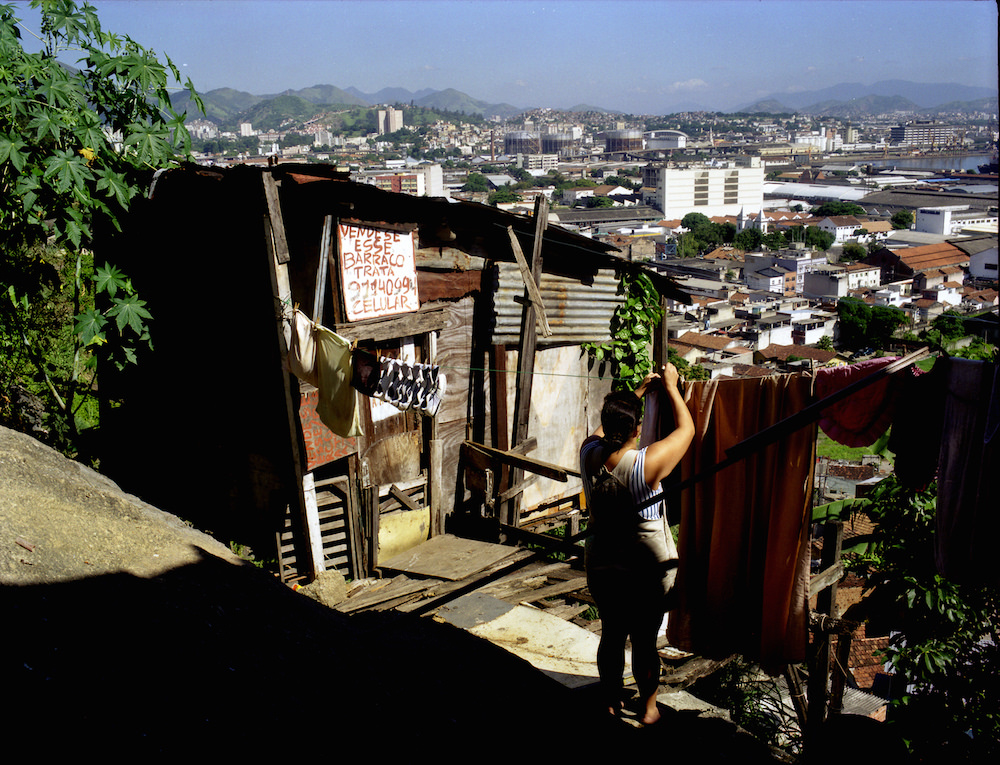

Simply defined, favelas are informal residential neighborhoods occupied predominantly by low-income families with minimal public services (Arias, 2004). Many have specific points of entry, delineating the boundaries of the settlement and making it possible to monitor who comes and goes. In Rio de Janeiro, favelas historically have been built spontaneously without authorization from the city government, and consequently lacked access to adequate infrastructure and public services such as schools, health facilities, piped water, electricity, paved streets, sanitation services, public safety and recreational space (Pino, 1997).

In the 20th century, waves of low-income families moved from rural areas in the northeast to cities in the southeast (Perlman, 2010). Driven by industrialization and natural causes, the poor moved to urban areas with hopes of a better life. The government encouraged this migration because it provided the low-wage labor necessary to feed industrialization. While many inhabitants moved to metropolitan areas in the Southeast in search of work, many others were forced to leave by land owners or cattle ranchers who received government land subsidies in an effort to encourage people to move (Dimenstein, 1991).

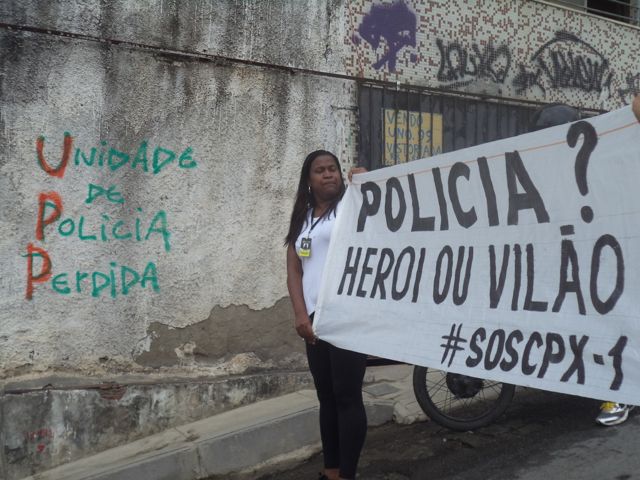

Migrants were relocated to peripheral areas of cities and were responsible for sorting out their own housing and communities with little to no investment from the public or private sectors. Today, favelas in Rio de Janeiro are growing at a faster rate in the poorer northern and western peripheral regions of the city compared to the more affluent south zone, so increasingly residents are physically isolated from the city center and its resources. Favelas are also violent; in addition to the penetrating and violent control of drug gangs, a disproportionately high number of citizens killed by the police are young favela residents (Amnesty International, 2015).

Consider the experience of José (pseudonym), who grew up in a favela roughly thirty minutes outside of Rio’s city center. José remembers classes being cancelled at his local public school when drug traffic conflicts made it unsafe to walk to school. His community’s single point point of entry and exit is guarded by heavily armed drug soldiers and leaving after dark can be dangerous; if he has evening plans outside of the favela, he does not return to his community until morning.

While the threat of physical violence has had a significant impact on his life, the physical and social isolation he faces is equally as difficult. José explained that if he wants to go to the movies, a museum, participate in continuing education courses, or enjoy the beach, he has to take a bus to the city center. Many buses pass the main avenue just outside of his community, but they are often crowded, and he never knows if the trip will take a half hour or an hour and a half. The metro does not reach his part of the city. Once in the center, he experiences overt racism and discrimination. Residents who live in informal settlements often face segregation and social exclusion on a daily basis (Perlman, 2010).

José desperately wants to attend university. However, he cannot afford the high prices of private university and he did not get the necessary marks on the college entrance exam to get into the more affordable option of pubic university. He knows virtually no one who knows or could advise him about higher education. After high school, he got a full-time job in the city center as an office boy where he earned roughly $200 a month. The cost of transportation ate up about a third of his salary.

Poverty and Mobility

José’s story offers an opportunity to explore the concept of mobility in what are commonly referred to as “emerging markets”. In the most traditional sense, José’s potential to move from point A to point B is constrained, and this physical constraint is tied to limits on other forms of mobility, including social mobility. For example, José’s formal education, an important mechanism for moving up the socioeconomic ladder, is limited when violence prevents him from walking to school, and later because of the cost of tuition. But even if he had been able to attend all of his classes, schools like his in the periphery of Rio de Janeiro are under resourced and far weaker than schools in the more affluent city center. Being physically isolated from the city center minimizes the possibility of accessing invaluable resources related to educational mobility, such as social capital in the form of mentors or role models. Next, José’s chances of achieving social mobility was limited by the lack of well-paying jobs in his neighborhood; working in the city center, he endures the economic and psychological effects of discrimination, while his commute ransacks his paycheck.

As we conceptualize mobility in this context, it is critical to flip our gaze to see that, just as Jose is socially insulated, so are Rio’s more affluent citizens. They lack the opportunity to interact with people from different socioeconomic backgrounds and informal neighborhoods, which feeds misunderstanding, fear and discrimination. They—and often we—fail to see how urban development and the social dynamics within the city perpetuate inequality.

Research in the “Global South”

As concepts of mobility become more nuanced, our notion of place becomes more relational and networked. What does this mean for private and public sector organizations working in the ‘global south’? How does this influence urban planning? How might we open up avenues for traditionally marginalized populations to access city resources in the center, and also shift social processes, structures and product/service development to evolve in the periphery to enhance mechanisms for social mobility? Who should be included in the mix to contribute to improving the quality of life of those living in informal neighborhoods, specifically when it comes to mobility?

It is critical that organizations interested in “emerging consumers” and doing business in the “global south” include residents of poor and informal communities in research and design processes. In Brazil, they can follow the lead of groups like Catalytic Communities, founded by Theresa Williamson. Theresa noticed that many informal urban settlements used innovative approaches at the local level to address immediate problems, but their lack of mobility prevented them from sharing their innovations or learning from other communities’ solutions. Her own financial position allowed her to travel easily among communities, so ironically, Theresa knew more about the myriad of innovative projects that existed within communities than the community leaders who helped orchestrate them.

Students, teachers, and community visit organisers gather in the small amphitheatre at the Bottom of Vidigal. Catalytic Communities via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Theresa began breaking down barriers to mobility by using Internet technology to disseminate information about innovative projects among community leaders. Today the mission of Catalytic Communities is to “create models for effective integration between informal and formal settlements in cities across the globe” to ensure that residents from informal settlements are fully integrated into the city. The RioOnWatch program, for example, addresses the overt absence of favela residents’ perspectives and experiences in mainstream media and news sources that cover stories about Rio’s favelas. It is a mobile news site published in Portuguese and English covering the most relevant topics that directly impact informal settlements.

Catalytic Community’s educational community visits are also a valuable resource for understanding the on-the-ground perspective of community residents. These customized educational visits led by community leaders offer an insider’s view of the unique context of the community for visitors in a position to influence broader public opinion and trends—researchers, students, journalists, entrepreneurs. The guides serve as invaluable key informants since they have strong ties to many people in the community. They have a wealth of information ranging from general demographics, to the inner workings of the politics of the community, to local “hotspots”. I had participated in a community visit in 2009 that provided rich contextual data for a study I was doing on social entrepreneurs at the time.

What are the implications for ethnography in industry, specifically with respect to ‘emerging consumers’ in the ‘global south’?

Nuanced understandings of space and mobility reveal the complexity of constraints faced by people in poor and informal sections of society. Importantly, they also reveal the constraints on the affluent, who fail to see the systemic causes of inequality and cannot access the important perspectives of poor residents or the innovative and entrepreneurial solutions they are already creating. In this context, we can learn a lot from organizations like Catalytic Communities and their practices:

- Catalytic Communities uses ethnographic techniques and leverages technology to bring awareness of the lived experiences of residents from informal neighborhoods to formal communities, as well as creating virtual spaces that support the exchange of ideas and open up possibilities of socioeconomic diverse networking.

- They bring people together who usually would never meet. In all of their programs they encourage connections among citizens from informal and formal spaces by facilitating on the ground access to community sources and testimonials, workshops, debates and educational community visits.

- Their philosophy and approach serve as a model not only for city planners, but also industry dedicated to achieving a double bottom line.

Ethnographic research has great potential to advance our understanding of the “emerging consumer,” which ultimately could encourage socially inclusive business practices, processes and innovations. To contribute to this exciting movement, I encourage you to submit a proposal to the EPIC2016 Paper Track, “Ethnography/Emerging Consumers.”

REFERENCES

Arias, E. D. (2004). Faith in our neighbors: networks and social order in three Brazilian favelas. Latin American Politics and Society, 46(1), 1-38.

Dowdney, L. (2003). Children of the drug trade: A case study of children in organized crime violence in Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: A Viva Rio Publication.

Dimenstein, G. (1991). Brazil, war on children. London: Latin America Bureau.

Amnesty International (2015) Brazil: ‘Trigger happy’ military police kill hundreds as Rio prepares for Olympic countdown. Retrieved on August 8, 2015 from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/08/brazil-trigger-happy-military-police-kill-hundreds-as-rio-prepares-for-olympic-countdown/

Human Rights Watch. (1997). Police brutality in urban Brazil. New York City: Human Rights Watch.

Penglase, R. (2005). The shutdown of Rio de Janeiro: The poetics of drug trafficker violence. Anthropology Today, 21(5), 1-5.

Perlman, J. (1976). The myth of marginality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Perlman, J. (2010). Favela: Four decades of living on the edge in Rio de Janeiro. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pino, J. (1997). Sources on the history of favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Latin American Research Review, 32 (3), 111-122.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2003). The challenge of slums:Global report on human settlement. New York: UN-HABITAT.

Laura Scheiber is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Pontifícia Universidade Católica, Minas Gerais, Brazil. She is studying innovations in education aimed at better meeting the needs of 21st century learners. She holds a PhD from Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research interests include marginalized urban youth, social learning, social entrepreneurship, sociology and international education. Laura is also a member of the EPIC2016 Program Committee.

Laura Scheiber is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Pontifícia Universidade Católica, Minas Gerais, Brazil. She is studying innovations in education aimed at better meeting the needs of 21st century learners. She holds a PhD from Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research interests include marginalized urban youth, social learning, social entrepreneurship, sociology and international education. Laura is also a member of the EPIC2016 Program Committee.

Related Articles

Redefining the Ivorian Smallholder Cocoa Farmer’s Role in Qualitative Research by Hannah Pick Calderón & Landry Niava (free article—sign in required)

Rethinking Financial Literacy with Design Anthropology by Marijke Rijsberman

Mannequins on My Mind: Addis Ababa and the Globalized Economy by Patricia Sunderland

0 Comments