Innovation in the startup world is broken. Startups say their aim is “disruption”—a riff on Christensen’s definition, but much less precise. “Disruption” has been appropriated by startups to mean doing something that has widespread, radical impact. They are about “changing the world.” They’re obsessed with the concept…but are failing on their own terms.

Unless you believe “changing the world” means doing “the things your mom no longer goes for you” (Arieff 2016). There are services that deliver beer to your door. Services that deliver X to your mailbox every Y months (razors, underwear, dinner kits). Apps to locate a rentable…anything. Not exactly revolutionary stuff.

Are we running out of good ideas for innovation? No, not really. There are plenty of startups with good ideas, but they face a huge number of barriers, and we seldom hear about them. The ones we do end up hearing about—well, those are the ones that got funding from venture capital firms (VCs). The problem with VCs is that they don’t actually try to fund the most innovative startups. They’re caught between what’s trendy and the biggest potential for a return.

Diffusion, not Disruption

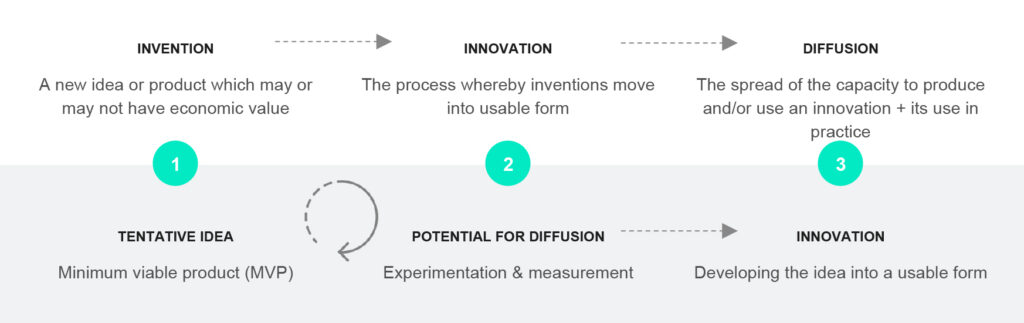

VCs fund the startups that can prove widespread, rapid diffusion, not innovation. The process of startup innovation has fundamentally shifted in the last decade, from one in which ideas were developed and then garnered funding, to one in which diffusion is the first and primary focus—before the innovation itself—making the flow looped or even backward.

This flow was not possible until recent years. Recent technological advances underlie the ability to measure and test global scalability even before committing a single line of code in the product. But the primary reason startups now work this way is to garner funding from VCs. And VCs want large capital gains within a short timeframe. In practice, this translates into a culture within the startup world that promotes creation of globally-focused, scalable, and profitable businesses. It privileges global scalability (diffusion) over what the actual technology is or how it is used.

The pace has also changed. Rather than really understanding the problem space or the market, there is a fast-paced drive to get something out. This inherently changes the types of “innovations” that make it to the market: even if they’re shooting for something radical, the process privileges things that are much more incremental. Almost completely absent is a focus on meaningful change.

A Meaningful Role for Ethnography

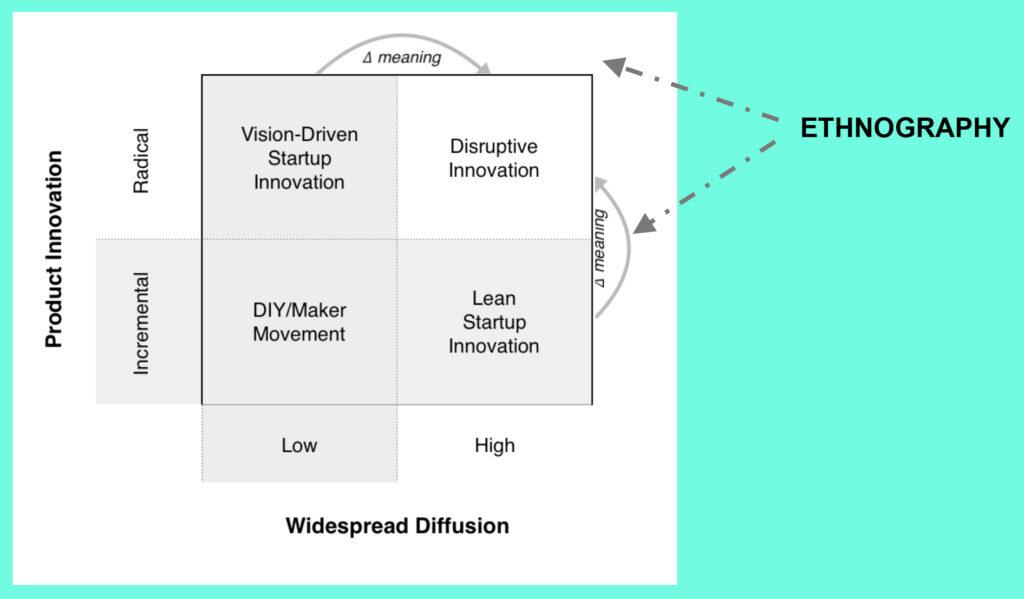

This tension between incremental and radical innovation is not new. Norman and Verganti (2012) have talked about this tension in design research and its role in shaping innovation. They suggest radical innovation is really either about a radical change in technology, or a radical change in meaning. But a change in technology that’s truly radical inherently entails a change in meaning as well, or the development of new meanings.

Taking this framework as inspiration, I have applied similar thinking to the types of innovation in startups from both product and process perspectives.

These four quadrants illustrate four types of startup innovation. Of course, these are not separate, mutually exclusive categories. This is a pretty fluid space. Startups can move within and between these quadrants.

It is the upper-right quadrant of disruption that is the sweet spot that much of the startup sphere is aiming for. And I’d argue that reaching this coveted area requires changes in meaning. You’re either widely diffused, but need to create a more meaningful difference for people; or you’re tech-forward and need to understand how you can provide a solution that is meaningful in a market. Either way, an ethnographic approach is uniquely positioned to explore such meaning.

Ethnographic approaches could be incredibly helpful for early stage startups, but there’s also a tight limit to their resources and capabilities. This isn’t true for VCs. It’s actually through working with VCs that we as a community can make the most impact—on startups, on the products they create, and on innovation.

Why VCs Need Ethnographers

VCs have tremendous power. They shape the startup sphere, in large part deciding who succeeds and who doesn’t. And while VCs are behind some of the most notable, innovative companies in the world, they are also very flawed. There are several overarching challenges for the VC model: identifying areas of opportunity and trends, and finding, funding, and fostering more innovative startups. Because of the challenges, VCs in general just don’t perform well for the risk they entail.

VCs have not out-performed the public market. Approximately 20 VC firms account for 95% of the return in the industry. The average VC fund actually fails to make a return on investor capital. In short, returns are unsatisfactory industry-wide, and venture capital underperforms as an asset class.

To put things bluntly, as Josh Kopelman, a well-known venture capitalist did: “for an industry that funds innovation – it really doesn’t have that much.” While some of the top VC firms have specific theses about the way they will invest or the domains in which they are keen to follow trends, much of the decision making relies on “thought leadership” and connections. Beyond these informed opinions, there are no general systems or methods for exploring potential domains, finding startups and making decisions on funding them. This is where ethnographers can help.

VC partners have the capital available to subsidize research, and the returns from having a more informed and thoughtful process would be worth the investment. Incorporating ethnographic thinking and research would innovate the VC model, which in turn could fund more innovative startups and hopefully foster more sustainable ones.

What’s in it for Ethnographers?

We can certainly help VCs with their bottom line, but why would we want to? In short, it’s because we could have a huge impact on expanding innovation into other areas, finding and supporting more diverse types of startups, and bringing reflection and values more to the fore in a sphere where they are typically ignored.

Currently in VCs, identifying areas of opportunity is often based on hunches, not research. There is a lack of knowledge about different global markets and minimal insight into burgeoning areas spreading tech innovations into other domains and industries. We can provide meaningful insights into different markets and domains, impacting their theses and expanding into important areas for innovation.

In finding new startups, known as “deal flow,” one of the biggest challenges is that VC firms rely on their internal knowledge and connections rather than solid ideas, and decisions are usually reactionary and informed by a herd mentality. We can focus on developing a more holistic process and deeper analysis. And we can help diversify the input beyond the affluent, educated, white male bubble that currently exists.

Making decisions around funding startups usually centers on hollow metrics. While there is a level of due diligence, the data sources are not great. We can bring in richer data for making these sorts of decisions—research that can help inform VCs of the real problems in an industry, highlight different, diverse perspectives, and understand what the metrics actually mean.

But the most exciting part is that our research could drive a better understanding of the world and how to create more meaningful impact. There’s an opportunity here to really push for more meaningful innovation. To push for disruption—positive disruption.

Disrupting VC

What does being a part of disruption really mean? Disruption suggests radical change in meaning alongside wide diffusion, but this perspective should also reflect on values, sustainability, and impact on the end user. Innovation is an important driver of the economy, but as much research has noted, this does not mean it is necessary or positive. The types of “value” inherent in a new concept or product need to be unpacked, and that is not easy or straightforward. As Graeber (2001) has proposed, ethnographic reflexivity can help us get to a more fruitful place.

The power of ethnographic methods and ethnographic thinking is not about finding new territory to colonize for startups and for VCs. In imbuing an ethnographic mindset into the main elements of the startup sphere, the goal is not to create disruption for the sake of a profit. It is to make innovation more meaningful. To drive value. And ethnographic approaches enable this in several ways.

The tools inherent in an ethnographic methodological approach allow for analysis of complexity in uncharted terrains. The focus on studying sociocultural contexts and their dynamics enables would-be innovators to anticipate change in social meaning. An interpretivist mindset underlies the ability to become attuned to a domain, a market, and importantly, an individual human who may be a user. And, finally, being reflexive allows us to understand value and to advocate for those values that make for positive change, not just disruption.

References

Arieff, Allison

2016 “Solving all the Wrong Problems.” New York Times, July 10, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/10/opinion/sunday/solving-all-the-wrong-problems.html

Graeber, David

2001 Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value. New York: Palgrave.

Norman, Donald A. and Roberto Verganti

2012 Incremental and Radical Innovation: Design Research Vs. Technology and Meaning Change. Design Issues, 30(1), 78–96.

Lead Photo: “Demo Focus Social and Media Technologies Sage Panel,” The DEMO Conference (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via flickr

Julia Katherine Haines conducts research at the intersection of technology innovation and human practices. She received her PhD in Information and Computer Sciences from University of California, Irvine. She also holds an MS in Human-Computer Interaction and an MA in Social Sciences. Julia is currently a User Experience Researcher at Google. hainesj@uci.edu

Julia Katherine Haines conducts research at the intersection of technology innovation and human practices. She received her PhD in Information and Computer Sciences from University of California, Irvine. She also holds an MS in Human-Computer Interaction and an MA in Social Sciences. Julia is currently a User Experience Researcher at Google. hainesj@uci.edu

Related

Goodbye Empathy, Hello Ownership: How Ethnography Really Functions in the Making of Entrepreneurs, Hiroshi Tamura et al

Bridging Ethnography and Path-finding Business Opportunities, ken anderson et al

The Ritual of Lean, Julia Katherine Haines

Iterating an Innovation Model: Challenges and Opportunities in Adapting Accelerator Practices in Evolving Ecosystems, Julia Katherine Haines

0 Comments