“There’s a lot of talk about us ‘being there’, and what that means for our practice and what that means for the type of work that we say we do. The ground has shifted. How do we respond to that? It’s not just, ‘Oh, we’re temporarily working remotely, let’s just gather some new tools.’ We’re actually responding to a shift in the ground underneath us. And we still want to be able to ask questions in depth and gather data in a way that makes meaning for us.”

—Nichole Carelock

Ethnographers are recalibrating the spaces we inhabit with people. We can’t physically go into homes, workplaces, stores, cars, hospitals; we’re adjusting interview protocols to online environments, exploring software for remote diary studies, and creating virtual workshops. But as we onboard new tools for ‘being there’ with people, let’s think about what it means to be there in the first place.

For decades ethnographers have pushed businesses and organizations to pay attention to places that seem counterintuitive to them. A business problem may focus on a defined industry or market, a growth target, a product feature. But when we translate that business problem into a research question, an ethnographic question, it turns out there are many places and spaces that matter.

Researchers routinely observe people using products or navigating a physical or virtual product or service journey. These central points of use are generally considered to be where the action is. But it’s far from the only place. Culture and meaning “happen” across space, place, time, and scale. The action we care about always happens in multiple sites and dimensions. So choosing research sites is about taking a position within these fields.

As Kris Cohen wrote for the very first EPIC conference, “the idea of people-as-users renders the social-cultural world as a series of use-instances.” An ethnographic lens doesn’t just contextualize, but also de-centers, this kind of product logic. So when ethnographers choose to ‘be there’, we are intentionally positioning ourselves to engage with other ways of creating meaning and assembling life; ken anderson argues, “Our goal is to see people’s behavior on their terms, not ours.” In a study of broadband Susan Faulkner noted, “People have meaningful ways of describing their internet connections at home that have nothing to do with the evidence cable providers or phone carriers use to track capacity, speed, and spectrum.”

We also situate ourselves conceptually, taking a strategic analytical position. In their study of energy use, Sarah Pink and colleagues took an explicitly “non-energy-centric approach” when they focused their key research question on sensory experience: How do people make their homes feel right?

“We saw how cats, dogs, the positions of light switches and power-points all impacted on the routes they took through their homes, and how the ways in which furniture and power points were arranged through the home played a part in narratives about how and why energy was consumed… Having TV, radio or music on contributed to the sensory feel of bedtime along with snuggling into a bed.”

Being in homes positioned Pink’s team to build an analysis across multiple scales and multidimensional places of energy use, from energy infrastructure, building codes, and product design, to ecological values, gender identity, and parenting. They found that “specific material, social and technological elements of home come together, in turn making un-economical uses of energy impossible to avoid even in households where people identify themselves through their attention to energy-saving.”

Similarly, Grant McCracken argues that relations among people and things—material, spatial, emotional, kinetic—are what transform space into home. These assemblages transform space into a workplace, public park, transit system, medical clinic, or school. For his work on retail strategy, Michael Powell sees the grocery store as a mediated space, a “curated collection of cultural products, a gallery of everyday life.” He positions himself there as both a researcher and a social mediator who “play[s] the role of mediating organizational relationships…to place product brands in their larger context of the consumer world, including the retail shelf, the supply chain and the retailer, more generally.”

It’s become something of a brand promise that ethnographers can deliver to our organizations a special kind of access to “real people” out there in the wild. But ethnography isn’t just about access to a place from which we can extract the data we need. It’s an analytic lens for being there. So in the upheaval of the pandemic, we need to do more than find a tool that best approximates the kind of access to a place we had before. We need to explore the spaces we can inhabit with people, reexamine our intentions, double down on analytic queries. As Nikki Carelock said, the ground is shifting. What positions can we take now?

There isn’t a roadmap for doing this, and even if there were a map for today, the ground will shift tomorrow. But in some sense, ethnographers have always thought deeply about how to position ourselves with shifting territory. Last week EPIC people gathered for a panel discussion on remote research to share guidance and inspiration as many of us take on new, remote positions. Here are some of the approaches we discussed, grouped in four themes with resources from epicpeople.org and beyond.

“The Field” is Multiple and Multi-Dimensional

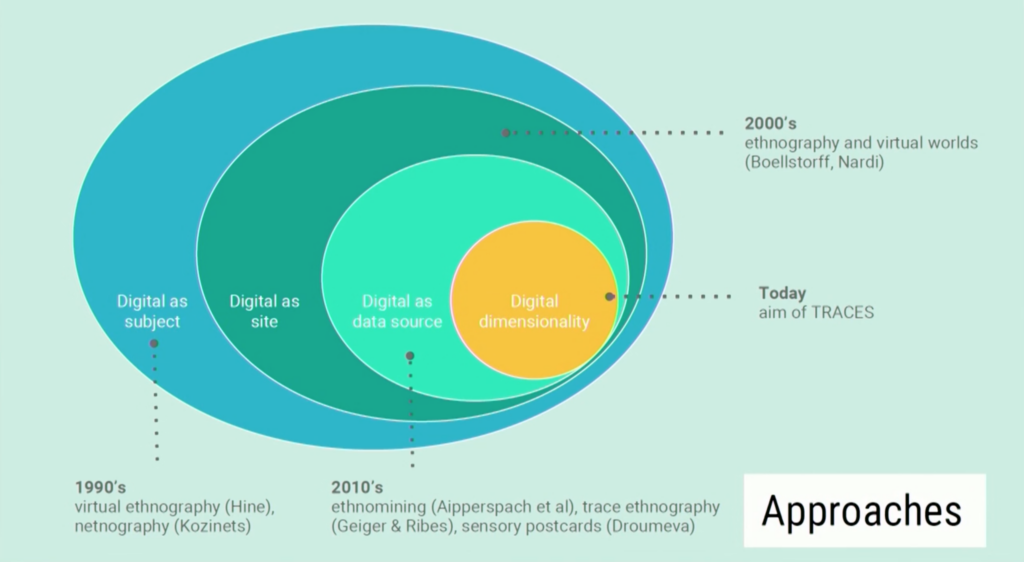

Julia Haines traced the evolution that led ethnographers from a focus on one specific, physical field site, to the conviction that ethnography should be multi-sited across many places, and then by extension that experiential spaces are not always physical, but are also virtual and ephemeral. Her approach TRACES emphasizes “the assemblages that constitute our lives, interweaving digital, embodied, and internal experiences. Various data streams and sources provide different vantage points for analysis and synthesis.” If some vantage points aren’t available to researchers right now, how can situate ourselves differently in spaces that are—spaces that are different, but no less “real”?

Julia uses field methods like remote experience and trigger sampling (see Bob Evans, PACO), diaries, device logging, reflection activities, and observation that take both emic and etic perspectives, and analytic methods from semiotics to algorithmic techniques. Dawn Nafus uses activity trackers and sensors in ethnographic research and analysis, both to “provide a trace of what goes on when the researcher isn’t there, and…help research participants reflect on their lives in a new way.”

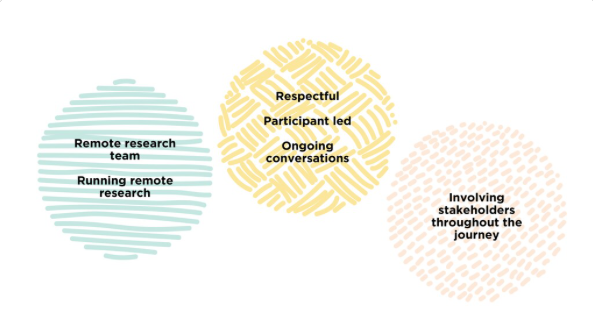

Participant- and Community-Led Engagement

As we reassess the multi-dimensional field and the positions we can take within it, we should reflect on the principles that guide our research relationships. Lee Ryan draws on her long-term practice of taking the lead from research participants and communities, a commitment beautifully articulated in Kataraina Davis and Rachel Knight’s talk about their integration of Maori principles into design processes. In the context of the pandemic and social distancing, Lee emphasizes the importance of a pause to ask: “How am I? What do we want to learn or do with whanau and is now the time? Will our work together enhance the mana of those involved? Are we prepared in ways that are useful?”

This is the groundwork for Lee’s successful use of that now-ubiquitous, blessed and cursed tool for social research and just about everything else—Zoom. She and colleague Natalie Rowland shares a Zoom-based project that sustained participant-led conversations for weeks or months across the globe, including key lessons her team learned, their suite of tools, and how they managed and analyzed voluminous video data. (She recommends the privacy guidance offered here and here).

Data and Insights are Co-created

As we rely more heavily on tools like remote diary studies, we might be concerned about the extent to which our data is now ‘more subjective’, created by participants who, famously, very often don’t behave the way they say the behave. But in one way or another, researchers and participants are always co-creating data. Susan Faulkner and Alex Zafiroglu grapple with this dynamic in their work on participant-made videos. They explore issues from the politics and performativity of self-presentation, to the assumptions stakeholders make about the authenticity or objectivity of data from, say, cameras and sensors.

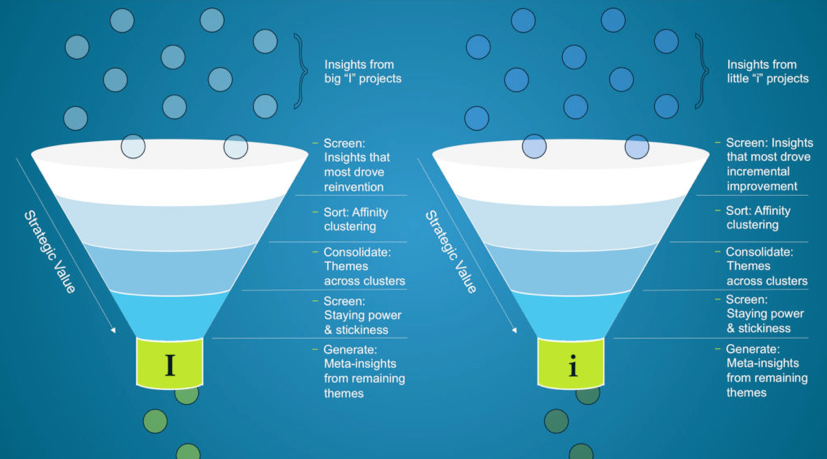

Tabitha Steager’s paper on interpreting the way participant frame information also offers useful frameworks for “ethnographic evidence and how as researchers we can “read” the evidence our participants create.” And Krista Harper’s tutorial on Photovoice covers this method as well as key concepts in the general field of participatory visual research.

Daria Loi offers three innovate cultural probes, which are tools that offer “a practical and creative way of learning more about people’s everydayness in a context where, due to privacy as well as time constraints, is not possible to conduct full participant observations.” She explores issues of context, time, audience, producer, content, soul, and purpose.

What about the photos, videos, and content of all sorts that people are constantly creating on social media—which offers accessible spaces researchers can inhabit during the pandemic? Kathleen Hartnett argues (with lots of excellent visuals!) that, “As a research source, social media behavior is often dismissed because of its orientation towards performance—but as people lead more omni-channel lives, the distinction between online and offline lives is becoming harder to discern. As such, we need to start viewing performative behavior as extensions of fully formed individuals.”

Ethnography and Strategy

Engaging directly with research participants may simply be off the table. Yet the ethnographic lens is still a crucial source of value for organizations.

As the pandemic upends so many assumptions underlying business strategy, we can revisit Jay Hasbrouk’s case for ethnographic thinking that asks “not just what consumers want, but why the organization is solving for that particular challenge in the first place.” Jay observes that companies with wads of user and customer research may nevertheless lack effective innovation strategies because this work isn’t analyzed holistically, or connected to a deep understanding of organizational cultures, adjacent cultures, and broader, emergent phenomena. Internal organizational ethnography combined with secondary research, competitive intelligence and industry landscape data, and other kinds of analysis can bring new strategic value to an existing body of research.

Many EPIC authors have focused on the value of ethnography for business strategy. Alex Jinich advocates for engagement with cost-cutting and operational efficiency measures (sadly happening in crisis mode right now for many organizations). Expanding beyond the logic of the balance sheet, our “holistic understanding of how value is experienced (and, hence, created) may allow us to know more precisely where and how to cut costs.”

anderson and colleagues also address a topic that is suddenly acute: risk and systemic volatility. To enable our organizations to interact with complex, volatile systems, they argue that “although working in situ remains important, the goal is no longer to describe or analyze the context but to understand the dynamic forces acting in these contexts.” With a variety of approaches in and out of the field, ethnographers can be “monitoring the social world… to understand what is normative, what is changing, and what might be perceived as an opportunity for stabilization and order.”

These strategic engagements require strong advocacy for the value ethnography in organizations at a time of massive instability, whether they’re experiencing collapse or growth. This is a profoundly collective endeavor.

References

anderson, ken. Ethnographic Research: A Key to Strategy. Harvard Business Review, March 2009. https://hbr.org/2009/03/ethnographic-research-a-key-to-strategy

anderson, ken, Tony Salvador & Brandon Barnett. Models in Motion: Ethnography Moves from Complicatedness to Complex Systems. 2013 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/models-in-motion-ethnography-moves-from-complicatedness-to-complex-systems/

Carelock, Nichole et al. Remote Workshops and Collaboration: “Being There” when You’re Not in the Room. EPIC Talk, April 7, 2020. https://www.epicpeople.org/remote-workshops-and-collaboration/

Cohen, Kris R. Who We Talk about When We Talk about Users. 2005 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/who-we-talk-about-when-we-talk-about-users/

Davis, Kataraina. Ka mua, ka muri; Look Back to Te Ao Māori to Advance Your Design Research. UX New Zealand 2019. http://www.uxnewzealand.com/speakers/kataraina-davis/

Evans, Bob. Paco—Applying Computational Methods to Scale Qualitative Methods. 2016 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/applying-computational-methods/

Faulkner, Susan. Invisible Evidence: Our Disconnection with Broadband Connectivity. 2018 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/invisible-evidence/

Faulkner, Susan and Alexandra Zafiroglu. The Power of Participant-Made Videos: Intimacy and Engagement with Corporate Ethnographic Video. 2010 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/the-power-of-participant-made-videos-intimacy-and-engagement-with-corporate-ethnographic-video/

Haines, Julia Katherine. Towards Multi-dimensional Ethnography. 2017 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/towards-multi-dimensional-ethnography/

Harper, Krista. Tutorial: Participatory Visual Research—Getting the Most from Collaborative Methods. https://www.epicpeople.org/participatory-visual-research-collaborative-methods/

Hasbrouck, Jay. Beyond the Toolbox: What Ethnographic Thinking Can Offer in a Shifting Marketplace. EPIC Perspectives, March 10, 2015, https://www.epicpeople.org/beyond-the-toolbox-what-ethnographic-thinking-can-offer/

Hasbrouck, Jay. Building an Innovation Strategy from Cultural Insights. EPIC Perspectives, April 30, 2018, https://www.epicpeople.org/building-innovation-strategy-cultural-insights/

Jinich, Alex. Of Cool Light and Balance Sheets: The Social Scientist as the CFO’s Best Friend. August 10, 2016, https://www.epicpeople.org/cool-light-balance-sheets-social-scientist-cfos-best-friend/

Laurent-Neva, Lucia. Applied Semiotics: Embracing Strategic Thinking and Fostering Innovation. EPIC Perspectives, May 26, 2016, https://www.epicpeople.org/applied-semiotics/

McCracken, Grant. Homeyness: A Cultural Account of One Constellation of Consumer Goods and Meanings. In SV – Interpretive Consumer Research, eds. Elizabeth C. Hirschman. Association for Consumer Research, pp. 168-183. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/12183

Mozilla. Privacy not Included. https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/

Lambe, Kaili. Tips to Make Your Zoom Gatherings More Private. Mozilla, April 3, 2020, https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/blog/tips-make-your-zoom-gatherings-more-private/

Loi, Daria. Reflective Probes, Primitive Probes and Playful Triggers. 2007 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/reflective-probes-primitive-probes-and-playful-triggers/

Nafus, Dawn. Tutorial: Getting Started with Sensor Data. EPIC Talks. Tutorial: Getting Started with Sensor Data. https://www.epicpeople.org/tutorial-getting-started-with-sensor-data/

Nafus, Dawn & ken anderson. The Real Problem: Rhetorics of Knowing in Corporate Ethnographic Research. 2006 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/the-real-problem-rhetorics-of-knowing-in-corporate-ethnographic-research/

Pink, Sarah. Digital Living and Sensory Perception: Implications for Ethnography and Design. EPIC Perspectives, April 14, 2015. https://www.epicpeople.org/digital-living-and-sensory-perception/

Powell, Michael G. Media, Mediation and the Curatorial Value of Professional Anthropologists. 2016 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, https://www.epicpeople.org/media-mediation-curatorial-value-professional-anthropologists/

Rowland, Natalie & Lee Ryan. Research Epic: How We Designed Immersive, Honest and Ongoing Conversations, Remotely. Design Research 2020. http://www.uxaustralia.com.au/conferences/design-research-2020/presentation/research-epic-how-we-designed-immersive-honest-and-ongoing-conversations-re/

Ryan, Lee & Jacob Otter. Preparing for Ethical Research and Co-design Practice in a COVID-19 Context. https://www.aucklandco-lab.nz/blogs/2020/4/20/preparing-for-ethical-research-and-co-design-practice-in-a-covid-19-context

Steager, Tabitha. Evidence Outside the Frame: Interpreting Participants’ “Framing” of Information when Using Participatory Photography. 2018 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. https://www.epicpeople.org/framing-information-participatory-ethnography/

Images:

1. from Haines 2017, “Figure 1. Approaches to digital ethnography over time,” https://www.epicpeople.org/towards-multi-dimensional-ethnography/

2. from Rowland & Ryan 2020, slide prepared by Natalie Rowland & redrollers

3. from Steager 2018, https://www.epicpeople.org/framing-information-participatory-ethnography/

0 Comments